<blogentry><entrydate month='01' time='21:15' daynum='05' day='13' year='2005'/> Day 5: Sing-a-long astronomy

Mark Peplow

Mark PeplowThere are dozens of posters here outlining 'outreach' programmes - different ways to tell the general public about astronomy, and why it's so wonderful. Virtually all are NASA-funded, and it's not too hard to take the cynical view that this is merely a sound investment aimed at keeping voters sweet while billions of their tax dollars are punted into space. Ten years ago, many astronomers looked down on this sort of thing, believing that it detracted from their research, says Dan Woods, part of NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington DC. Now it's widely accepted, and most astronomers do some kind of outreach activity, he says.

And what better way to communicate the joy of astronomy than through the medium of music? That's the strategy of The Chromatics, a six-strong a cappella group that performs around Washington DC and whose members mostly work at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Centre in Maryland. The group formed in 1995, and two years later got a NASA education grant to produce 500 cassettes of astronomy-themed songs along with activity books for school kids.

Almost ten years later "this is really on the verge of taking off in a big way", says bass singer Alan Smale (also program executive for mission operations and data analysis at NASA headquarters, and a fiction writer). The group sustain the project with sales of their AstroCappella CD, now used as a teaching resource across the United States, and have recently had a song incorporated into a planetarium show in Atlanta. Enthusiastic teachers say that the astronomical details in Lunar Love, High Energy Groove and Habitable Zone are much easier for kids to remember in musical form.

The group now mix the astronomy songs into their normal setlist. "At first we were reluctant to sing these songs for general audiences," says member Padi Boyd. "Would people who came to have fun at a concert really enjoy a song extolling the virtues of the 21-centimeter neutral hydrogen line?" she asks. Apparently so - Doppler Shift is now their most requested song at gigs.

I'm not going to sharpen my critical teeth on the music, but you can make your own judgements at http://www.astrocappella.com. One particular highlight is Dance of the Planets, a wistful tale about the search for planets outside our Solar System, where Boyd sounds exactly like Sandy Denny with a PhD. Oh come on, you remember Sandy Denny? Sang in Fairport Convention, died tragically after falling down a flight of stairs...?

</blogentry><blogentry><entrydate month='01' time='23:15' daynum='05' day='13' year='2005'/> Day 5: Hi!

I keep seeing results about 'HI' in space. I'm told this stands for 'hydrogen one' in Roman numerals - otherwise known as neutral hydrogen atoms. So won't it get confusing if we find hydrogen iodide - with chemical formula HI - in space? "Wow, I never thought of that," gasps one young astronomer. "That's gonna be a major problem," adds his colleague, a worried look creasing her brow. Hey, calm down, I'm sure we can work something out.

</blogentry><blogentry><entrydate month='01' time='17:52' daynum='04' day='12' year='2005'/> Day 4: He just keeps going...

The amazing Steve Squyres show has rolled into town. As the head of the science team for NASA's Mars rovers Spirit and Opportunity, Squyres has been speaking at pretty much every space and earth sciences conference for the last year. I bump into him as he nurses a coffee, looking very, very tired. How many of these presentations have you given now, Steve? "They all blur into one," he smiles. But he insists that he never gets bored, because there's always some new discovery to reveal. As he talks about Mars, the tiredness lifts and ten years fall away from the man. What a trooper.

I sit in on his show. I've seen it before. So have the other thousand people that pack out the conference centre's ballroom. That doesn't stop them laughing at the same old jokes, and applauding in all the right places. Everyone's eyes are lit up, and not a single person is doodling or checking emails on their laptops. I'd call that a success.

</blogentry><blogentry><entrydate month='01' time='20:15' daynum='04' day='12' year='2005'/> Day 4: Poster children

Most conferences have poster sessions, where scientists print their latest research results onto large sheets and pin them to boards for all to see. More than at any other conference I have been to as a scientist or a journalist, the poster sessions here are true social gatherings, complete with beer and popcorn for all. It attracts a surprisingly strong crowd of students and post-docs, too. The combination leaves me with the impression that astronomers are by far the liveliest scientists around. This needs to be subjected to a proper test, I think...

</blogentry><blogentry><entrydate month='01' time='18:45' daynum='03' day='11' year='2005'/> Day 3: Cool toys

While not hunting for cool stuff in space, astronomers spend their spare time inventing new ways to look for cool stuff in space. The UltraLightweight Technology for Research in Astronomy (ULTRA) team, for example, are making lightweight telescopes using graphite mirrors rather than glass. The graphite can be baked onto a precisely finished template, rather than spending forever-and-a-day grinding a glass mirror into perfect shape. You can use the template over and over again to produce identical mirrors - useful for larger telescope that may contain hundreds of mirror segments. And the graphite is incredibly light. Their prototype telescope has a 40-centimeter-diameter mirror, and the whole thing weighs in at around 10 kilograms. The equivalent telescope using a glass mirror would weigh ten times as much. "This could change the way all telescopes are made in the future," says team leader Paul Etzel from San Diego State University, gleefully picking up his telescope to prove the point.

Meanwhile, the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope is taking shape. It will use a three-gigapixel digital camera to record vast swathes of sky in exquisite detail. Yes, that's right - that's about a thousand times the number of pixels in your personal digital camera. Just like a particularly nimble football player, "it can go fast and wide and deep all at the same time," enthuses Tony Tyson from the University of California, Davis. He reckons that the telescope will generate 30 terabytes of data each night - that's about 80 CDs of data every minute. All the observations will be freely available online, although with that much information I fear they might break the internet.

</blogentry><blogentry><entrydate month='01' time='21:25' daynum='03' day='11' year='2005'/> Day 3: Feeding frenzy

I have to say, the press conferences here are extremely well organised. Gathering the best of the day's scientific highlights into media-friendly, bite-sized chunks is not easy, but the AAS press officer Steve Maran has done a cracking job. The scientists making their 5-minute presentations have mostly been primed for the job, too. One after another, they introduce presentations with "I'm going to start with my conclusions", "The bottom line is ..." or "If I had to describe my work in one sentence...". It’s straight out of the press officer's handbook; you can spot it a mile away. It's formulaic but it makes my life a lot easier.

The downside to this is that the reporting can become something of a treadmill. One journalist for a daily American newspaper lamented that he'd love to be able to go to the main scientific talks, but there was always a risk that it wouldn't generate a story. In good press conferences the news is served pre-masticated, and if your editor's demand for the day is "I need 80 lines from you, and I don't care what it's about", it's just too risky to waste half a day digging around for stuff when reliable stories are being served to you on a plate, he says. Does this mean that as science communication becomes more organised, the news becomes more homogenous? Does it really matter? Answers on a postcard, please.

</blogentry><blogentry><entrydate month='01' time='9:35' daynum='02' day='10' year='2005'/> Day 2: Star sign

For those not hardy enough to brave the mud-slicked streets, a shuttle bus has been laid on to ferry people the ten-minute walk between hotel and conference centre. I haven't used it myself, but I'm reliably informed that it carries a sign telling people that its destination is the 'American Astrological Society'. Slightly embarrassing, but then I would say that, being a Gemini...

</blogentry><blogentry><entrydate month='01' time='17:15' daynum='02' day='10' year='2005'/> Day 2: Long-lost records refound

Bradley Schaefer, an astronomy historian from Louisiana State University, is already in full flow when I arrive for his talk. He certainly wins the award for the shoutiest man of the day, as he sets out the case for his discovery of the long-lost star catalogue of Hipparchus – or at least a way to reconstruct it.

Schaefer argues that the Farnese Atlas, a Roman sculpture made in 129 BC that depicts more than 40 constellations on a globe, was carved by someone who relied on Hipparchus for their astronomical details. Because the positions of the constellations in the sky change over time, Schaefer worked out that the key observations were made in 125 BC, give or take 50 years – exactly when Hipparchus was supposed to have made his catalogue, according to contemporary historians. He says that using the Atlas as an authentic version of Hipparchus's catalogue could help historians resolve arguments about how much of his work was copied by Ptolemy when the latter wrote his astronomy masterwork, the Almagest. The room is packed for the talk, and the applause enthusiastic – I think they're convinced, and not just by the shouting.

</blogentry><blogentry><entrydate month='01' time='18:10' daynum='02' day='10' year='2005'/> Day 2: Excuse me?

Funniest quote of the day (on a press release about the Doppler effect): "A similar phenomenon happens with the sound of a passing car on a highway, going 'eeeeeeyyoool'." Excuse me? Is that five 'e's or six?

</blogentry><blogentry><entrydate month='01' time='20:35' daynum='02' day='10' year='2005'/> Day 2: Picture perfect

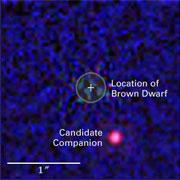

© NASA/ESA/G. Schneider

© NASA/ESA/G. SchneiderOne presentation here today is good news for those excited about the possibilities of directly observing planets outside out solar system and taking their pictures. Last year, one team of European Southern Observatory scientists saw one such possible planet orbiting a small, faint brown dwarf called 2M1207 about 230 light years away (see 'Rival teams race to snap alien planet'). While discovering the existence of an extrasolar planet isn’t such a big deal, actually ‘seeing’ it is – usually astronomers work out that the planet is there by indirect methods instead, such as watching for wobbles in the orbits of nearby, larger objects.

Now, follow-up observations with the Hubble Space Telescope have confirmed their results, upping the chances of their siting actually being a planet to 99% – the best candidate for a direct sighting yet. "Further planned Hubble observations are required to eliminate the 1% chance that it is a coincidental background object that is not orbiting the dwarf," says Glenn Schneider of the University of Arizona, who presented the research today.

</blogentry><blogentry><entrydate month='01' time='17:15' daynum='01' day='9' year='2005'/> Day 1: A party filled with life

Undeterred by the intense storms that are lashing America's west coast, about a thousand people turned out for this conference's welcome reception. Martin Rees, Britain's astronomer royal, held court as the star guest of the gathering, while hungry astronomers destroyed the free buffet. And it was nice to see that astronomers can still be thrifty, despite using multimillion dollar equipment at work - a queue to fill up water bottles quickly formed in the men's washroom, consistent with grumbles about the shockingly expensive bar.

I had an enjoyable chat with a prospective extrasolar planet hunter whose project is, for the moment, finding favour with the NASA gods. The Terrestrial Planet Finder (TPF) is an orbiting telescope that is still in the project development phase, and may launch in the middle of the next decade. NASA has just agreed to turn TPF into two separate telescopes that will work at visible and infrared wavelengths, boosting their ability to spot Earth-like planets around other stars. People around the table agreed that TPF, and several other missions on the slate, will finally allow scientists to make reasonable predictions about how many planets in the Universe could support life - until now it has been pretty much guesswork, they say.

There was also much talk about NASA's change in direction, and what it means for research budgets. With the agency now focussed more on exploration and life hunting, everyone is scrambling to find an astrobiology angle to their work, admitted one Jet Propulsion Laboratory scientist here. People studying interstellar chemistry or looking for new planets are generally feeling pretty secure, while others fear that NASA may abandon more fundamental astrophysics research into how the Universe works. The trouble is, confides one worried scientist, there's no way such projects could be funded through universities, and research in those areas could begin to dry up. This might leave the European Space Agency as the only body with the financial clout to mount missions that look for strange physics instead of bug-eyed monsters.

</blogentry>