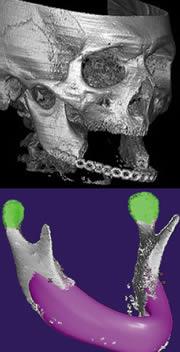

A 3-D scan was taken of the patient's jaw (upper) and used to generate a virtual jawbone (lower).Warnke et al.

A 3-D scan was taken of the patient's jaw (upper) and used to generate a virtual jawbone (lower).Warnke et al.A cancer survivor has enjoyed his first solid meal in nine years after receiving a custom-built, bioengineered jaw transplant. The marvellous mandible is one of a kind: it was designed by computer, built in the laboratory, incubated in the patient's back, and then grafted into his face.

The 56-year-old man, who had part of his jawbone removed after a tumour spread through the area, tucked into a plate of bread and sausages just four weeks after a three-hour operation to fit the replacement.

Patrick Warnke from the University of Kiel, Germany, and his colleagues describe their procedure in this week's Lancet1. They hope their approach will be safer and more effective than alternative transplant methods.

"We are cautiously optimistic," he says. But it is still early days: the operation was performed just nine weeks ago, and so far only one person has received the treatment. "We need to assess more patients on a longer timescale before drawing any firm conclusions about the procedure's efficacy," he says.

Making the mould

The team took a three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) scan of the man's head and used computer software to design a perfectly fitting, virtual jawbone. From this, the researchers created a scale model made of Teflon.

They then fitted a lightweight titanium mesh around the replica, and removed the Teflon to leave a perfectly sculpted, hollow, U-shaped tube.

The cylinder was filled with a natural bone mineral called hydroxyapatite, blood from the patient's own bone marrow, and a dash of a chemical called bone morphogenetic protein 7 (BMP7). The bone mineral offered structural support as BMP7 coaxed stem cells inside the blood to form new bone.

Next, the replacement jaw needed to develop its own blood supply, so the team grafted it into a region rich in blood vessels under the man's right shoulder. Seven weeks later, medics removed the mandible and slotted it into the skull. "It was a perfect fit," says Warnke. Microsurgery was used to connect the jaw's newly developed blood supply with that of the head.

From the hip

The procedure is an advance on alternative methods, where surgeons remove bone from hip or leg bones and carve it into a rough jaw shape before grafting it into the face.

"The jaw is rarely a perfect fit," says Warnke of the older method, and it injures the hip or leg. This can cause pain and joint problems.

The new technique has improved the patient's quality of life, says bone marrow expert Stan Gronthos from the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science in Adelaide, Australia. Before the operation, the patient had a cosmetic, titanium jawbone that was covered with skin. Although this looked reasonably normal, the patient was unable to chew and dined solely on soft food and soup.

Warnke aims to recruit extra patients for more custom-built jaw transplants, and hopes that others will use his method. Around 10% of surgery centres worldwide are set up to perform operations like this, says Warnke, so there is nothing to stop the technique being used elsewhere.