Is it too late to keep global warming

below 1.5 °C?

The challenge in 7 charts

Chances are rapidly disappearing to limit Earth’s temperature rise to the globally agreed mark, but researchers say there are some positive signs of progress.

When representatives from 197 countries arrive in Dubai this month for the latest round of climate negotiations, they will have to confront a basic question: are nations meeting the goal they set of limiting global warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels?

This will be the first time that humanity formally assesses its progress under the 2015 Paris climate agreement. The goal of this mandatory ‘global stocktake’ is to ensure that political leaders face the facts every five years, with the hope that they will then strengthen their efforts to curb emissions of greenhouse gases. Countries must follow up with new climate commitments in 2025.

On the positive side, it’s now clear that many governments are taking concrete steps to mitigate climate change. Climate investments are increasing in both the public and private sectors, and renewable sources of energy are displacing fossil fuels at historic rates in many countries. But progress is much too slow, and by almost any measure the world is falling far short of the 1.5 °C goal. Greenhouse-gas emissions are at an all-time high, tropical forests are being chopped down at near-record rates, fossil-fuel subsidies are going up and coal-fired power stations are still being built.

“Heading into the global stocktake, governments need to be clear-eyed about this lacklustre progress so that they can jump-start an urgently needed course correction,” says Sophie Boehm, who tracks climate trends for the World Resources Institute, an environmental think tank in Washington DC.

Here, Nature takes a hard look at the progress so far, and what it would take to keep the Paris dream alive.

Record heat

At first glance, it seems that nations have no chance of meeting the Paris agreement’s headline goal of limiting warming to 1.5 °C. The rate of warming has picked up over the past decade, and the average global temperature for 2023 is likely to be 1.4 °C above the average for 1850–1900 (see ‘Rising temperatures’).

“The political reckoning is coming soon,” says Detlef van Vuuren, a climate scientist at the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL) in The Hague, who uses models to assess future climate, energy and economic trends.

At this rate, it could be less than a decade — possibly much sooner — before global warming reaches 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels. Natural variations, such as the current El Niño warming in the tropical Pacific, can significantly influence temperatures in the short term. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) uses 10- and 20-year rolling averages when it calculates Earth’s surface temperature. This means there can be a long lag between the official IPCC estimate of global warming and the average temperatures in any given year.

“We could effectively hit 1.5 degrees of warming each year for a whole decade before the long-term average passes that mark,” says Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist at Berkeley Earth, a non-profit organization in California that tracks global temperatures.

It won’t stop there. Models that use projected carbon emissions estimate that global temperatures will increase by 2.4–2.6 °C above pre-industrial values by 2100, on the basis of current pledges that countries have made as part of the Paris agreement.

Delay doesn’t pay

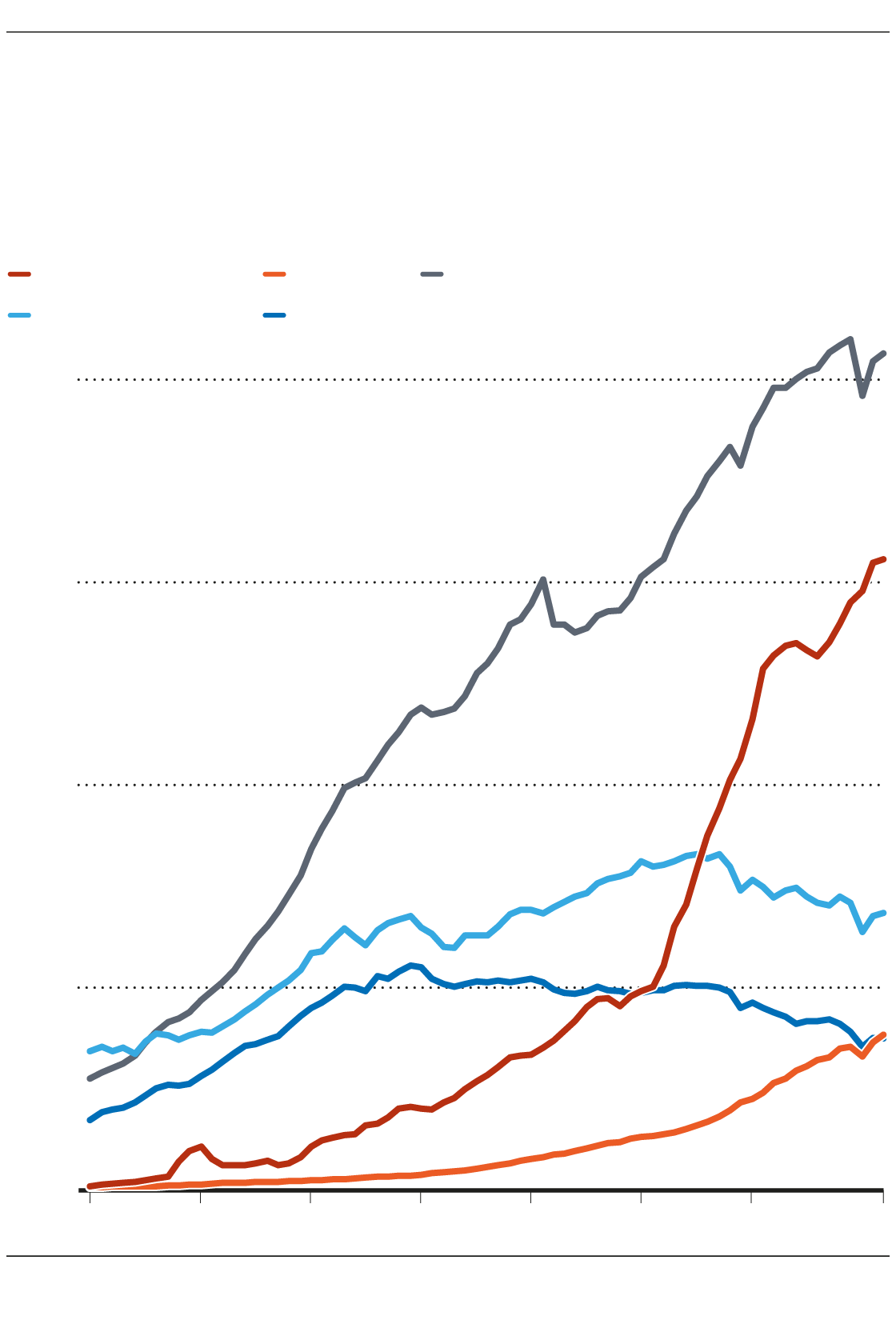

One thing is clear: the longer we wait, the harder it becomes to achieve the Paris goals, and experts say we have waited much too long. Global leaders committed to preventing “dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system” when they signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1992. Had they honoured that commitment and pressed forwards with emissions reductions at that time, they would have had a century to halt greenhouse-gas emissions and still limit warming to 1.5 °C.

The picture looks different three decades later. On the basis of current emissions trends, the world will burn through enough carbon to cause around 1.5 °C of warming in a little over five years, according to the latest carbon budget estimates from Climate Change Tracker, a scientific consortium that tracks climate trends using IPCC methodologies. The world would need to reduce carbon emissions by 8% each year between now and 2034 to maintain a 50% chance of staying below 1.5 °C of warming.

By comparison, it took a global pandemic to reduce carbon emissions by 7% in 2020. “We’ve put ourselves in this stupid mess by not acting sooner,” van Vuuren says (see ‘The cost of delay’).

Nations signed the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1992. If world leaders had started curbing emissions then, they would have had nearly a century to eliminate carbon emissions and keep warming below 1.5 °C.

In 1997, industrialized countries first agreed to specific emissions targets by adopting the Kyoto Protocol. If the world had started reducing emissions then, there would have been about 75 years to zero out emissions.

At this point, the world has about 12 years to stop pumping carbon into the atmosphere to limit warming to 1.5 °C.

Source: Berkeley Earth

Carbon removal

With no real hope of such drastic action to cease emissions, the consensus among researchers is that there’s only one viable way to dig out of this mess. That is to overshoot the 1.5 °C mark for a time and then dial temperatures back down in the latter half of the century by extracting carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

This overshoot scenario is one of the top choices of computer models that are tasked with finding the cheapest path forwards, and it’s one reason why many scientists continue to say the goal is still, technically, achievable.

Scientists and businesses are pursuing a range of often-controversial options for removing carbon from the atmosphere, also known as negative emissions. Some focus on nature-based activities, such as planting forests and subtly altering ocean chemistry, to promote carbon uptake. Others use industrial solutions, including capturing and burying emissions from power plants and steel mills or extracting CO2 directly from the atmosphere.

The problem is that none of the carbon-removal methodologies has been demonstrated at anything close to a climate-relevant scale, and the potential knock-on effects are often poorly understood. Even planting forests, for instance, can harm biodiversity or inflate food prices through the loss of agricultural land. But with enough investment and research, many scientists expect that negative emissions will ultimately have to play a part.

“It’s important to develop backstop technologies for carbon removal, and I’m fairly confident that we’re going to be able to do it,” says Sally Benson, an energy engineer at Stanford University in California. A bigger question, she adds, “is whether we will be willing to spend the money”.

Assuming a cost of US$100 per tonne to extract CO2 from the atmosphere, a common target for carbon-removal technologies, Hausfather says it would cost some $22 trillion to sequester enough carbon to reduce global temperatures by just 0.1 °C. That is roughly 16 times more than the annual climate expenditures by governments and businesses worldwide last year. “We’re talking about very, very expensive interventions,” Hausfather says.

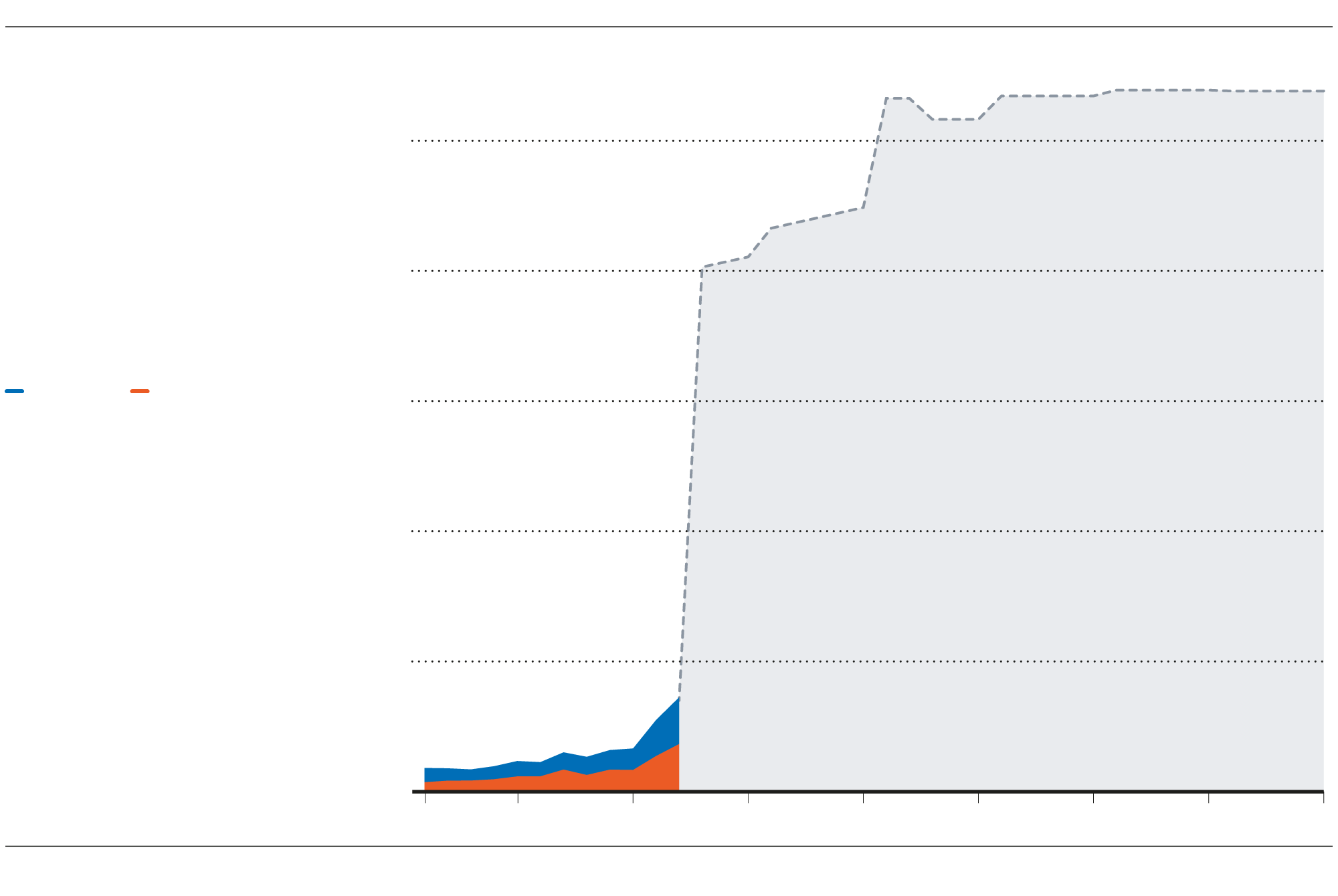

This is one reason why scientists invariably stress the need to first drive down emissions as quickly as possible (see ‘Negative emissions’).

To achieve the Paris agreement goals, many models analysed by the IPCC suggest that the world will need to go beyond eliminating carbon emissions.

Some time after 2050, nations will probably need to extract carbon out of the atmosphere to limit warming to 2 °C (light orange).

If nations want to keep the global temperature rise below 1.5 °C (blue), models indicate that huge amounts of carbon would need to be removed from the atmosphere beginning in the next few decades.

Source: Adapted from Fig. SPM.5, IPCC AR6 Synthesis Report

Curbing emissions

After a one-year dip caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, global CO2 emissions from fossil fuels hit a new high of 37.2 billion tonnes last year. Rates of renewable energy generation are also surging, however, and many energy experts now consider the transition away from fossil fuels all but inevitable. This is one of the few bright spots heading into COP28.

Even in the face of inflation, war and a concomitant energy crisis, clean-energy deployments have increased to record levels. Clean technologies are attracting the bulk of new energy investments around the world, and it seems that fossil fuels are poised for an imminent, albeit slow, decline.

All of this has led the International Energy Agency to project that annual emissions from fossil fuels — which account for more than 90% of all carbon emissions — are set to peak in the next few years and drop to 35 billion tonnes by 2030. Compared with a baseline projection from 2015, before the Paris agreement was signed, that would represent a reduction of 7.5 billion tonnes per year, which is equivalent to eliminating the energy emissions from the United States and the European Union combined (see ‘Peak emissions’).

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, emissions were climbing rapidly, roughly in line with a baseline projection made before the Paris climate agreement.

The pandemic caused a momentary drop in emissions, which then surged again. But thanks to growth in the market for clean-energy technologies, the IEA projects that global fossil-fuel emissions will peak in the next few years.

The expansion of solar energy is responsible for much of the emissions reductions, relative to the pre-Paris baseline forecast.

Wind power and the rapid increase in the number of electric vehicles are also helping to drive down emissions.

By 2030, emissions are expected to drop by 5% compared with 2022.

Source: Adapted from Fig. 1.3, IEA Net Zero Roadmap 2023

“The bottom line is that we’ve reached a point where the growth of clean energy technologies is really hard to stop,” says Pol Lezcano, an energy analyst at the consultancy BloombergNEF (BNEF) in New York City.

Cleaner electricity

Moving forwards, the first step is to hasten that progress and clean up the electricity grid. In many places, Lezcano says, this means removing bottlenecks by upgrading and expanding power-transmission lines in coordination with new projects for electricity generation. “The pace needs to be much, much faster,” he says.

But the potential pay-off is enormous. A new electricity grid supplied by abundant clean energy could also heat buildings and power electric vehicles. “Those things together will get you a 50% reduction in emissions,” Benson says, “and that is reason for hope.”

The path ahead is daunting. Electricity from renewables and other low-emission sources will need to increase by almost sevenfold to nearly 77 trillion terawatt hours annually by 2050, according to the International Energy Agency. Generation from coal, gas and oil must drop to almost zero by 2040, unless accompanied by technologies that capture and somehow sequester carbon from the atmosphere (see ‘Green grids’).

To achieve this transformation, the IEA projects that wind and solar would need to account for roughly 70% of electricity production by 2050.

Low-carbon sources of electricity will need to increase by about sevenfold, producing more than four times as much electricity in 2050 as coal, natural gas and oil generate today.

Source: Adapted from IEA Net Zero Roadmap 2023

But that’s the easiest part. Much more complex will be cleaning up sectors such as heavy industry, aviation and long-haul transport — as well as agriculture and food systems. And nations need to reduce emissions of other greenhouse gases, too.

Of particular interest is methane, which accounts for around 16% of total emissions. Reducing emissions of this powerful greenhouse gas is one of the only ways that nations can slow the rate of warming over the next few decades. What’s more, modelling scenarios for 1.5 °C used by the IPCC assume that humanity will do exactly that. This also means that temperatures could rise even faster than projected over the next few decades if the world fails to act on methane.

Shifting responsibilities

Industrialized countries in the global north are responsible for the bulk of the greenhouse gases that have accumulated in the atmosphere. The United States and Europe, for example, have emitted 37% of the historical total. But emissions from the wealthiest Western countries have been declining for decades, whereas the share from other nations has soared. China is now the world’s largest CO2 emitter, and just this year India’s CO2 emissions passed those of the European Union (see ‘Biggest emitters’).

The expectation from the beginning, when the UN climate convention was signed, was that wealthy countries would lead the way in reducing emissions and developing clean energy technologies. To an extent, that is now happening: much of the clean energy deployment is occurring in the United States and Europe, Lezcano says. But the largest driver of the current energy revolution is China.

BNEF estimates that China will add more than 200 gigawatts (GW) of solar capacity alone this year, compared with 34 GW in the United States and 48 GW in the European Union. China’s factories have also helped to drive down the price of solar panels, enabling the industry to expand well beyond its borders.

This is all good news, but the industry ultimately needs to spread to the rest of the world. Apart from China and a few other countries such as Brazil and South Africa, Lezcano says, green energy has been slow to penetrate low- and middle-income countries, where emissions from fossil fuels are rapidly rising.

Increasing investments

Another flash of good news going into COP28: global climate investments — including both private and public spending — skyrocketed to $1.1 trillion in 2021 and $1.4 trillion in 2022, according to the latest analysis from the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI), an international advocacy group. All told, that represents a near doubling from the previous two years.

“This is a step change,” says CPI analyst Baysa Naran, who is based in London. “I’m definitely encouraged.”

Yet it’s just a start. The CPI estimates that the world will need to increase climate spending to around $9 trillion annually by 2030 and to nearly $11 trillion by 2035 to roll out clean sources of energy and prepare for the inevitable impacts of a warming climate during the next few decades (see ‘Climate finance’). More money will also need to flow to low-income countries.

Naran says there is more than enough funding floating around: governments invested nearly $12 trillion in economic relief during the COVID-19 pandemic, and are currently spending more than $1 trillion per year on direct fossil fuel subsidies (or $7 trillion if indirect incentives such as regulatory relief are included). Rolling those subsidies back is no simple matter because of the potential effects on the world’s poorest citizens, Naran says, but it is yet another source of money as the world looks to the future.

As with so many things, Naran says the question once again boils down to choices. “If you put effort into it, things can happen,” she says. “It’s just a matter of urgency and political will.”