Abstract

Purpose

To determine the proportion of uveal melanoma patients who accept cytogenetic prognostication and to understand the reasons for their decision and the psychological impact of an adverse prognosis.

Methods

Patients treated by enucleation or local resection for uveal melanoma between 01 January 2003 and 31 December 2006 were identified and the proportion undergoing cytogenetic studies was determined. In-depth interviews of fourteen patients living near our centre were conducted to determine their reasons for accepting cytogenetic testing and their reactions to any results received.

Results

In total 97% of 298 eligible patients with uveal melanoma treated by enucleation or local resection accepted an offer of cytogenetic prognostication. None of the patients interviewed in detail expressed any regret about having this test and there was no evidence of any harm. The main benefit perceived by patients was that they would have greater control and that screening for metastatic disease and early treatment might enhance chances of survival. This was despite counselling that prognostication, screening, and treatment are unlikely to prolong life and that the main purpose of cytogenetic studies is to allow for life-planning.

Conclusions

Almost all patients with uveal melanoma desire cytogenetic prognostication, although not for the reasons intended by their medical practitioners. Further studies are needed to understand patients' reactions to cytogenetic testing, so that care can be optimised.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Uveal melanoma is fatal in about 50% of all patients.1 Almost all metastatic deaths occur in patients whose melanoma shows partial or complete loss of chromosome 3 on cytogenetic testing.2, 3

Since 1999, all patients with uveal melanoma undergoing local resection or enucleation in Liverpool have been offered cytogenetic testing of their tumour for prognostic purposes. Those with a disomy 3 melanoma were given reassurance that their life expectancy was not significantly worsened by their tumour. Patients with a monosomy 3 melanoma were referred to our medical oncologist with special expertise in ocular melanoma (EM), who informed them in person of their prognosis and counselled them about screening for metastatic disease, also providing this service if it was desired by the patient.

We describe here our approach to cytogenetic testing and how we attempt to mitigate any psychological distress caused by this investigation. We evaluated its acceptability in two ways. First, we determined the proportion of patients who accepted an offer of cytogenetic studies. Then, by detailed interviewing of a sample of patients, we sought to understand the reasons for their decision and the psychological impact of a poor prognosis.

Methods

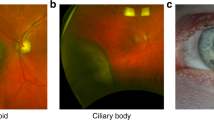

Ophthalmic assessment

At initial assessment, each patient underwent visual acuity measurement by a nurse; systematized history-taking and initial ocular examination by a trainee ophthalmologist; ocular photography by a specialised photographer; and assessment of the tumour by slit-lamp examination, ophthalmoscopy and ultrasonography by the consultant ocular oncologist (BD).

Counselling

After assessment, the consultant ocular oncologist counselled the patient about the diagnosis, the natural history of the disease, and the therapeutic options together with the risks and benefits of each form of treatment. Patients were informed of the survival prognosis after confirming that they wished to receive this information. If planned treatment was enucleation or local resection, the patient was told words to the effect: ‘If you wish, we can perform a special laboratory test which will tell us whether or not the tumour is life-threatening. We can do this test only if you want to know the result, good or bad. If you get a good result, this will be very reassuring and you will probably feel better than you are perhaps feeling now. If you get a bad result you will be offered screening tests by an oncologist. However, the chances of prolonging life are small and the main benefit for you may be life-planning.’ The patient was then given the opportunity to ask questions. The entire conversation was audio-recorded and an audiocassette was given to the patient to take home.

The patient was then escorted to an adjacent quiet room by a specialist nurse who reviewed all that was said, providing encouragement and consolation as necessary. Each patient was given information sheets about their selected treatment and about cytogenetic studies.

Postoperative counselling

Some patients returned to their local hospital for enucleation, either at their request or on the instruction of the referring ophthalmologist. Most underwent treatment at our centre within a day of their initial assessment and were visited on their first postoperative day by the health psychologist (SC) who assessed psychological status and organized psychological monitoring and support if necessary. After discharge from hospital, all patients were (1) telephoned by a specialist nurse within a week and by the health psychologist if significant distress was identified; (2) reviewed by their local ophthalmologist within a month; and (3) reviewed by the consultant ocular oncologist after 6 months, unless enucleation had been performed in which case follow-up at our centre was not considered necessary.

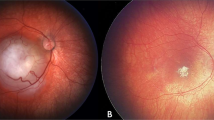

Management according to cytogenetic results

Cytogenetic studies using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and histological investigations were performed as described elsewhere.3 We now estimate the prognosis according to clinical tumour stage, histological grade of malignancy, cytogenetic type, and normal life expectancy of the age-matched population. This is done using a neural network we have developed, which generates a patient's personalised survival curve (Damato et al, unpublished data).

Patients with a disomy 3 melanoma and low-grade histological features (ie no epithelioid cells, no closed loops and low mitotic rate) received a letter from the consultant ocular oncologist (1) explaining that their life expectancy was almost normal (not entirely normal because ‘no test is foolproof’) and (2) inviting them to discuss the result with our specialist nurse by telephone. Copies were mailed to the patient's referring ophthalmologist and general practitioner.

If the melanoma was of monosomy 3 type, a copy of the cytogenetic report was mailed by the consultant ocular oncologist to the referring ophthalmologist and general practitioner together with a letter informing them that (1) the patient had been treated for a melanoma that was found on cytogenetic testing to be associated with a poor prognosis for survival; (2) treatment of metastatic disease only rarely prolongs life, unless resection of isolated metastases is possible; (3) screening for systemic metastases would involve abdominal ultrasonography and biochemical liver function tests every 6 months indefinitely; (4) opinions regarding the value of such screening are divided; and (5) the patient was being referred to our medical oncologist. We now include a printout of the patient's personalised survival curve with this letter.

On being informed of a patient with a monosomy 3 melanoma, the medical oncologist (EM) wrote to the patient, with copies to the referring ophthalmologist and family doctor (1) inviting the patient to Clatterbridge Centre for Oncology for notification of the cytogenetics result and (2) explaining that this could be organized at a local hospital for patients unable to travel. Patients who attended Clatterbridge Centre for Oncology were (1) informed of the result and its significance by the oncologist, who also provided emotional support as necessary and (2) offered participation in a trial of screening, which comprised six monthly biochemical liver function tests and magnetic resonance imaging. Patients who were unable to return to Clatterbridge for notification of the cytogenetics results or for screening were referred to an oncologist at their local hospital.

Patients developing metastatic disease were investigated and either (1) referred to a hepatic surgeon if imaging suggested that metastases might be resectable; (2) offered palliative chemotherapy; or (3) offered entry into any ongoing clinic research programmes of chemotherapy.

Evaluation

Determining the proportion who chose cytogenetic prognostication

The ocular oncology database was searched for all patients resident in the United Kingdom who had enucleation or local resection for uveal melanoma between January 2003 and December 2006 and were therefore eligible for cytogenetic testing. Case notes of all patients without cytogenetic data were reviewed to determine why this investigation had not been performed.

Detailed interviewing

Patients were selected at random from the ocular oncology database from those who met the following inclusion criteria: (1) known cytogenetic status; (2) residence within 60 miles of Liverpool; and (3) treatment by enucleation or local resection for uveal melanoma 12–48 months previously. After confirming with their general practitioner that they were not undergoing a current illness-related crisis, patients were asked by letter for consent to interview. Additional new patients were approached 1–2 days postoperatively and asked for consent to be interviewed up to three times over the course of the following 18 months.

In-depth interviews were conducted in the patient's home, lasted 22–65 min and covered (1) decision-making about the test; (2) understanding of cytogenetic testing; (3) reasons for wanting prognostication; (4) understanding of risk of metastatic death; (5) understanding of test results, and (6) reaction to results. The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analysed using established qualitative methods, which ensure findings that reflect patients' experience rather than the researchers' preconceptions.4 We report components of the patients' accounts that were common across the sample.

Results

Proportion of patients who chose cytogenetic prognostication

Between 2003 and 2006, 338 patients underwent surgical tumour excision, which consisted of enucleation in 309 patients, trans-scleral local resection in 27 and trans-retinal endoresection in 2, and were therefore eligible for cytogenetic studies. These patients (192 men, 146 women) had a median age of 65.3 years (range 21–97) and resided in England (298), Scotland (7), Wales (22), or Northern Ireland (11).

Of these patients, it was not possible to perform cytogenetic studies in 26, either because they had undergone enucleation at their local hospital (N=25) or because they were unable to provide informed consent (N=1). For 14 patients reasons for the lack of cytogenetic studies could not be identified, either because the case notes could not be located (N=7) or because the relevant information was not documented (N=7). Of the remaining 298 eligible patients, 288 (97%) chose cytogenetic prognostication, and cytogenetic results were available for 278 of them. For 10 consenting patients cytogenetic studies failed, provided an uncertain result or were not possible. Just 10 (3%) eligible patients declined testing.

Detailed interviews

Of 29 patients identified as eligible from the ocular oncology database, general practitioners permitted contact with 18. Of 14 successfully contacted, 9 consented and 7 (2 men and 5 women, aged 54–75 years) were interviewed 14–44 months after initial treatment. One patient had declined testing; the others had accepted it. Of the five who had received a poor prognosis, one had resectable liver metastases and one had terminal metastases. Of nine new patients approached postoperatively, seven consented and were interviewed, five of whom received a poor prognosis; all were interviewed before receiving their results and six were also interviewed 1–4 months after.

Consequently, the sample was 14 patients (seven from the database and seven new patients) who provided a total of 20 interviews.

The single patient who had declined testing was the only one who regretted the decision. All patients who chose the test were positive about their decision, despite 10 having been informed of a poor prognosis before being interviewed. Typically, patients said that they could not understand why someone would not want to know their prognosis because having this information made it easier to cope. No patient described feeling harmed by the results. Indeed, all described benefiting, even when results indicated poor prognosis. Some who were interviewed before they received their results thought the test would help life planning. However, no patient who had received results described using them in this way. They avoided thinking about their prognosis, explaining that they did not want to worry about the future. Instead of helping life planning, patients valued results for two reasons. Merely having the information provided a sense of control. They also gained hope from believing that the regular monitoring that followed a poor prognosis result would increase their chance of survival. In describing this, they referred to the widespread public belief that early detection and treatment of cancer increases survival and that ongoing medical research may result in new treatments in the future.

Discussion

This study found that almost all patients accepted an offer of cytogenetic testing, despite being told that the chances of prolonging life were small. Moreover, there was no evidence that patients who received results indicating poor prognosis regretted their decision. Indeed, the only patient who regretted her decision had declined testing. Similarly, there was no evidence that patients were harmed by having the test or could not cope with prognostic information. However, patients' views of the benefits of cytogenetic prognostication diverged from what they were told before testing; they gained a sense of control, linked to hope that screening for metastases and early treatment would improve their chances of survival.

The high proportion of patients choosing cytogenetic prognostication provides incontrovertible evidence that almost all patients with uveal melanoma wished to know as much as possible about their risk of developing metastases. The main weakness of the study is its limitation to residents of the United Kingdom who were treated in Liverpool. The results might not generalise to other centres, especially in other countries. However, our finding is consistent with a recent review that concluded that most patients with early stage cancers of many kinds want prognostic information, although the type and quantity wanted varies between individuals and over time.5

A further limitation is the small number of patients who were interviewed in depth so, although patients' views were consistently positive in this sample, we cannot exclude the possibility that some patients might be harmed by an adverse prognosis. Future studies could test the generalisability of our findings by using standardised quality of life instruments in larger samples. We are not aware of previous reports of the psychological impact of cytogenetic studies of uveal melanoma or any other cancer. Indeed, it has previously been highlighted that the psychological consequences of using tumour markers to predict cancer outcomes are virtually unknown.6 Furthermore, a recent review identified a need for research into the impact of prognostic information on patients' psychological state.5 Our preliminary study suggests no long-term adverse psychological effects of prognostic information for uveal melanoma, even when this indicates poor prognosis. This is consistent with evidence of the psychological impact of genetic and other tests that indicate risk of future illness. Although psychological distress is common immediately after adverse results, this soon dissipates.7, 8 However, most studies of genetic testing have been in healthy individuals, and its effect may be different after experiencing cancer.9, 10

Several questions arise from finding that cytogenetic testing created false expectations about improving survival. How did this misconception arise, when patients were told explicitly that prognostication, screening, and treatment of metastatic disease rarely prolonged life? Was this a form of denial, and a coping mechanism? Is it ethical knowingly to allow patients to retain such false hopes, or should more be done to ensure they fully understand their prognosis and the ineffectual nature of current medical interventions? Should more be done to encourage patients with a poor prognosis to sort out their affairs, before they become unwell? We are planning to address these matters in future studies.

Our clinical impression is that it is patients with good prognosis who benefit most from cytogenetic testing; however, formal investigation should test this view. We intend to explore this using standardised quality of life measures. One would expect that distress would be relieved by reassurance that a tumour is not as malignant as originally believed so that life expectancy is essentially normal. We are aware of some patients, however, who were unduly sceptical of such news. We have therefore addressed this problem by providing patients with objective evidence supporting their good prognosis and encouraging them to discuss this with our specialist nurse. About 5% of patients with a disomy 3 melanoma develop metastatic disease after being told they have a good prognosis.3 We plan to investigate how these patients react to their misfortune, having initially been given the wrong prognosis.

There is also scope for investigating why a few patients decline cytogenetic studies. It is difficult for some patients to decide ‘on the spot’, especially at the end of a stressful consultation and after receiving a great deal of information. We now give patients the option of cytogenetic testing of their tumour but with the laboratory subsequently withholding the results from all medical practitioners involved in their care and from them. This has been necessary because the FISH studies we performed required fresh tumour tissue; however, we have recently started using laboratory techniques that are possible with fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue.

There were 25 patients who did not have cytogenetic studies because their enucleation was performed at their local hospital. We need to understand whether these patients were disadvantaged in any way. Similarly, during this study, there were patients who did not have any cytogenetic testing because they were treated with radiotherapy. Further investigations are needed to determine whether in such patients the risks and expense of biopsy for cytogenetic studies are justified by any psychological benefits.

In addition to considering patients' reactions to cytogenetic testing, this article also described the logistics of providing psychological care. When we first started cytogenetic prognostication in 1999, if patients lived far from our centre we attempted to give bad news by telephone or by asking their ophthalmologist or general practitioner to speak to them on our behalf. It soon became apparent that such methods were unsatisfactory and that distressing information should be given by an oncologist in person and with facilities for providing adequate emotional support. Although we have attempted to provide our patients with information and counselling at various stages of the care pathway, this study has revealed misconceptions, as described above, which need to be addressed.

In conclusion, cytogenetic testing of uveal melanomas has important psychological consequences, which must be better understood if patient care is to be optimized.

References

Kujala E, Mäkitie T, Kivelä T . Very long-term prognosis of patients with malignant uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003; 44: 4651–4659.

Prescher G, Bornfeld N, Hirche H, Horsthemke B, Jöckel KH, Becher R . Prognostic implications of monosomy 3 in uveal melanoma. Lancet 1996; 347: 1222–1225.

Damato B, Duke C, Coupland SE, Hiscott P, Smith PA, Campbell I et al. Cytogenetics of uveal melanoma: a seven-year clinical experience. Ophthalmology 2007; 114: 1925–1931.

Elliott R, Fischer CT, Rennie DL . Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. Br J Clin Psychol 1999; 38: 215–229.

Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PM, Dimitry S, Tattersall MH . Communicating prognosis in cancer care: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Oncol 2005; 16: 1005–1053.

Fertig DL, Hayes DF . Considerations in using tumor markers: what the psycho-oncologist needs to know. Psychooncology 2001; 10: 370–379.

Shaw C, Abrams K, Marteau TM . Psychological impact of predicting individuals' risks of illness: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med 1999; 49: 1571–1598.

Broadstock M, Michie S, Gray J, Mackay J, Marteau TM . The psychological consequences of offering mutation searching in the family for those at risk of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer—a pilot study. Psychooncology 2000; 9: 537–548.

Meiser B . Psychological impact of genetic testing for cancer susceptibility: an update of the literature. Psychooncology 2005; 14: 1060–1074.

Schlich-Bakker KJ, ten Kroode HF, Ausems MG . A literature review of the psychological impact of genetic testing on breast cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns 2006; 62: 13–20.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the Liverpool Ocular Oncology Centre (LOOC) and Clatterbridge Centre for Oncology for their cooperation, and the patients of LOOC for giving freely of their time to participate in research interviews.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cook, S., Damato, B., Marshall, E. et al. Psychological aspects of cytogenetic testing of uveal melanoma: preliminary findings and directions for future research. Eye 23, 581–585 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2008.54

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2008.54

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Choroidal biopsies; a review and optimised approach

Eye (2023)

-

Fear of prognosis? How anxiety, coping, and expected burden impact the decision to have cytogenetic assessment in uveal melanoma patients

Supportive Care in Cancer (2022)

-

Psychosocial impact of prognostic genetic testing in uveal melanoma patients: a controlled prospective clinical observational study

BMC Psychology (2020)

-

Psychosocial impact of prognostic genetic testing in the care of uveal melanoma patients: protocol of a controlled prospective clinical observational study

BMC Cancer (2016)

-

Assessment of the effect of iris colour and having children on 5-year risk of death after diagnosis of uveal melanoma: a follow-up study

BMC Ophthalmology (2014)