Key Points

-

It is important to establish what is motivating the patient to seek treatment. There may be tangible or intangible reasons and the clinician needs to be clear what health gain is to be achieved.

-

The challenge revolves around balancing the autonomy of the patient's desire for cosmetic treatment with the downsides of intervention.

-

Consent is integral to ensure mutually satisfying treatment is provided.

Abstract

After the demise of the Industrial Age, we currently live in an 'Information Age'1 fuelled mainly by the Internet, with an ever-increasing medically and dentally literate population. The media has played its role by reporting scientific advances, as well as securitising medical and dental practices. Reality television such as 'Extreme makeovers' has also raised public awareness of body enhancements, with a greater number of people seeking such procedures. To satiate this growing demand, the dental industry has flourished by introducing novel cosmetic products such as bleaching kits, tooth coloured filling materials and a variety of dental ceramics. In addition, one only has to browse through a dental journal to notice innumerable courses and lectures on techniques for providing cosmetic dentistry. The incessant public interest, combined with unrelenting marketing by companies is gradually shifting the balance of dental care from a healing to an enhancement profession. The purpose of this article is to endeavour to answer questions such as, What is aesthetic or cosmetic dentistry? Why do patients seek cosmetic dentistry? Are enhancement procedures a part of dental practice? What, if any, ethical guidelines and constraints apply to elective enhancement procedures? What is the role of the dentist in providing or encouraging this type of 'therapy'? What treatment modalities are available for aesthetic dental treatment?

Similar content being viewed by others

What is the difference between aesthetic and cosmetic dentistry?

The first point to clarify is the distinction between aesthetics and cosmetics. Aesthetics is an artistic concept, conceived by artists at an attempt to relate their paintings to nature. However, in the Greek Empire, scientists tried to define aesthetic beauty by mathematics in order that it could be predictably reproduced, not just for paintings, but other forms of art, crafts and architecture. The protagonist for scientific aesthetics was Pythagoras, who devised the Golden Proportion, which combined with dynamic symmetry, discovered in the 1920s by Jay Hambridge and Sir D'Arcy Thompson, explained natural occurring beauty and how it could be reproduced in arts, crafts and architecture.2 Therefore, a simplified definition of aesthetics is beauty that is in synergy with form and function, as predominantly occurs in nature. Cosmetics, on the other hand, are concerned only with beautifying, very often without any consideration to form or function. Cosmetics aims to exaggerate or highlight form beyond that which nature intended. For example, breast enlargements to proportions that are rarely observed in nature, having little to do with natural form or function. A dental example would be 'paper white' teeth, which rarely occur naturally and have no beneficial advantages to form or function.

Although the above definitions attempt to differentiate aesthetics and cosmetics, there is widespread ambiguity and both terms are synonymously used to describe anything beautiful. This confusion is present among professionals as well as laypersons. In addition, subjectivity plays a major part when defining aesthetics and cosmetics, for example it is arguable that larger breasts or whiter teeth do serve a function by increasing chances of attraction, and should therefore be classified as aesthetics. Alternately, this point of view can be perceived as fickle and serving no purpose except beautifying, and therefore breast enlargement or whiter teeth should be classified purely as cosmetic. Whichever view one subscribes to is a matter of personal choice, and neither is right nor wrong. However, for the purpose of this article, aesthetics will be defined as beauty + form + function and cosmetics as only exaggerated beauty.

Why do patients seek cosmetic/aesthetic dentistry?

A patient may seek an improvement of their dentition for either tangible or intangible reasons. Tangible reasons include discoloured, misaligned, missing, broken, worn or heavily restored teeth. In these cases the patient has a legitimate desire to rectify the aesthetic anomalies for either a health investment and/or longevity of their dentition. The patient shown in Figure 1 has undoubted reasons for seeking an aesthetic improvement of his anterior misaligned dentition. A diagnostic wax-up proposes the possibilities achievable with contemporary dental treatment (Figs 2 and 3).

Pre-operative plaster cast of patient in Figure 1

Diagnostic wax-up showing proposed alignment and aesthetic improvement of anterior dental aesthetics for patient in Figure 1

The second category of patients seek dental improvement for intangible reasons, which can be divided into narcissism, psychological or personality disorders, or career and social progression. Narcissistic individuals are hedonistic, egotistical and have a high opinion of themselves. They are also vain or trying to regain their lost youth. Many of these patients may or may not have tangible reasons for dental improvement, and usually insist on a 'dental makeover' for nothing more than cosmetic reasons, eg 'whiter or straighter teeth' for relatively minor irregularities. The patient in Figures 4 and 5 requested a dental makeover because she disliked the discolouration, left lateral facial rotation and minor incisal edge wear of the central incisors. This case is an ideal candidate for bleaching with possible composite fillings to replace the minimal tooth loss. However, preparing six or even eight teeth for laminates is grossly destructive and highly unethical, irrespective of patient demands.

Patients with psychological disorders are probably the most difficult to decipher and manage. Examples include obsessive emulation of celebrity demi-gods and pathological preoccupation with self and social image, usually seen as more important than health issues.3 Other causes are inner inadequacy or resolving past traumatic events unrelated to the dentition, synaesthetic perception4 (even if health, function and aesthetics are achieved, the result is deemed a failure by the patient), somatic elusion, transference and body dysmorphic disorder.5 A pitfall to avoid is when another person is paying for the dental treatment, for example parents or partner. In these situations the dentist has to satisfy both the patient and the paymaster. These 'back seat neurotics' can themselves be suffering psychological problems, such as a parent absolving their guilt for lack of attention to their siblings during childhood, or an overtly obsessive partner fearing rejection. If such manifestations are suspected, the dentist should consider referral to a psychologist. This may be perceived as pejorative, but we should reconcile ourselves to the fact that as dentists, we are not trained psychologists.

Lastly, a patient may wish to improve anterior dental aesthetics for either career and/or social progression, even though there is no health justification for such procedures. While the patient may view this as legitimate, should the dentist oblige to satisfy the patient's wishes? If so, consider the following: what if the patient does not get 'that job', or 'that person' is not physically attracted to them? Who is to blame? The dentist?

Are enhancement procedures a part of dentistry?

Treatment is described as any therapy that has health benefits, using the principle that the benefits outweigh the potential risks and cost. For example, the benefits of treating carcinoma with chemotherapy, radiotherapy or invasive surgery outweigh the risks and cost associated with these therapies. Similarly, the benefit of providing a dental filling to alleviate pain and restore function outweighs the risks of a local anaesthesia. But compare the medical situation of exposing the patient to general anaesthesia for cardiac surgery with that for liposuction. Which procedure has a higher benefit to risk ratio? A dental example would be whether it is justifiable to file down one or more healthy anterior teeth for crowns or veneers in order to match the shade of a single crown on a discoloured tooth.

Elective treatment can be categorised into that which does, or does not affect health and function. Assuming no postoperative complications, examples of treatment with little or no impact on health and function are rhinoplasty, blepharoplasty, breast augmentation or liposuction. Although elective treatment may initially be innocuous, it nevertheless places the individual in a vulnerable position, with possible impact on health and function at a later date. Examples of complications may be side effects of general anaesthesia, postoperative infection or relapse, and irreversible disfigurement or morbidity as a result of the original 'corrective' procedure. A dental example of an elective procedure is extraction of a healthy tooth to satisfy aesthetic demands, which may later result in migration of adjacent or opposing teeth, hindering mastication or compromising phonetics.

The conflict for a medical or dental practitioner is health vs enhancement. Curing a disease is for attainment of health, while enhancement is providing treatment other than for somatic health reasons. There are innumerable questions and conflicts between health and enhancement, for example is ugliness a disease?6 Is aging a malady? Should Botox or other skin enhancement procedures be regarded as therapeutic? Is happiness linked to appearance? Ideally, the word 'treatment' should be reserved for therapy, which endeavours to restore health and function by combating a disease that jeopardises an individual's health, with a high benefit to risk ratio.7 Therefore, to clarify terminology, it is proposed that the word 'treatment' describes true healing therapies, while 'procedures' describes elective or enhancement modalities. Furthermore, for enhancement procedures one cannot apply the 'benefit/risk/cost' criteria since these modalities are beyond the scope of achieving health.

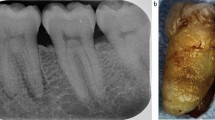

The most ubiquitously used restorations for cosmetic dental procedures are porcelain laminate veneers (PLVs). As a general dictum, PLVs should be reserved for replacing lost dentine and enamel, but not used as a substitute for dentine and enamel. For example, providing PLVs following tooth wear or for heavily restored teeth with defective large restorations has a high benefit/risk ratio (Fig. 6). However, providing PLVs to alter the shade of healthy teeth from A3 to B1 has a low benefit/risk ratio, and is highly contentious and potentially harmful. While PLVs deliver immediate gratification, the negative aspects include possible pulpal damage, infection, fractures, or even tooth loss, especially if carried out by inexperienced operators. In fact, providing PLVs in these situations amounts to little more than amputation and mutilation, irrespective of the outcome or the reasons presented to justify these procedures.

What are medical ethics?

Aesthetic or cosmetic dentistry occupies the middle ground on an ethics continuum where on the one extreme is 'right' and the other extreme is 'wrong'. An example of 'right' is providing a restoration for a broken tooth, thereby restoring health and function. At the 'wrong' extreme is extracting a healthy molar at the request of a female patient for achieving a concave, slender appearance of the lower part of the face to accentuate the maxillary skeletal structures, in the hope of progressing her modelling career.8 The above-cited examples leave little room for disagreement and most practising clinicians would be in consensus. However, for aesthetic or cosmetic dentistry, objectivity is less forthcoming and is trumped by subjectivity.

In daily practice, clinicians are faced with dilemmas and challenges regarding treatment planning. What is the right treatment option for the patient? What is the right treatment option for the business? Which is the most suitable restorative material for a given clinical scenario?9 Before discussing the conflicts between best for the patient and best for the business, it is important to clarify what constitutes medical ethics. Ethics encompass the following four entities:

-

1

Nonmalfeasance – doing no harm (the Hippocratic principle) – perhaps not pleasing patients' wishes, but at least not harming them

-

2

Beneficence – well-being of the patient

-

3

Autonomy – veracity in clinician-patient relationship

-

4

Justice – fairness and impartiality.

To be strictly ethical, adherence to all four of the above is a prerequisite. If one or more item is omitted, ethics are compromised. However, in reality, one or more items predominate at the sacrifice of the others. Compromises are usually apparent due to differing opinions of a patient and clinician, with one party dominating and the other accepting.

What is the role of the dentist regarding aesthetic/cosmetic treatment/procedures?

The role of a dentist in providing cosmetic procedures or aesthetic treatment is threefold: professional, clinician and businessman or businesswoman. If the truth be told, at times an egalitarian equality of the three responsibilities is challenging or impossible.

Professional

Medical or dental professionalism is defined as a combination of vocation plus ameliorating health and function. As stated above, cosmetic procedures lie outside this definition, ie beautifying without necessarily having health or functional benefits. The difference between a hairdresser, tattoo artist or other non-professional and a professional is that if a non-professional's clients are not satisfied with their services, personal litigation is the only recourse. Conversely, if the services of a professional are shortcoming, the offender may be criminally prosecuted. The positive aspect of being a professional is that they enjoy a higher social stature and respect, but they are also burdened with greater responsibility.

The next aspect of professional behaviour is balancing paternalism with patient autonomy.10 Paternalism implies an authoritarian attitude, knowing the best course of action and unilateral decision-making without patient involvement. Taking paternalism further would amount to assertiveness or belief in a particular treatment modality, withholding information about negative aspects of a given treatment/procedure, coercion, and swaying for a favourable acceptance from a patient who has limited knowledge or is ignorant. The last aspect is especially true for aggressive marketing tactics such as sexing-up the outcomes and benefits of a given procedure for the sake of ensuring that the patient signs on the 'dotted line.'

On the other side of the fence is patient autonomy, ie a patient's right to choose and request a given treatment option which may or may not be in assent with the clinician's opinion. If a patient is insistent on seeking enhancement which is beyond achieving health, then they should take responsibility for their actions and accept that such procedures are not covered by medical/dental ethics and if problems occur they have no recourse to professional ruling bodies for compensation, ie caveat emptor – the buyer, not supplier is responsible for purchased commodities or services.

While the above are the darker sides of paternalism and patient autonomy, the aim is to achieve a middle ground where both parties are comfortable. There is no doubt that a professional is more qualified to advise a layperson regarding a specific service. If the clinician presents, with judicial marketing, the positives and the negatives of a service, he/she has performed their professional duty to inform and educate the patient. It is then the patient's right to choose the desired course of treatment or procedure. Ultimately, an individual has the autonomous right to do what they want with their bodies. Similarly, the dentist also has the right to refuse the requested procedure if he or she feels that it would compromise their professional status. If such a cul-de-sac arises, the patient is free to seek advice elsewhere but the reluctant dentist has retained his or her professional integrity.

A worrying aspect regarding professionalism is the burgeoning of 'cosmetic clinics' throughout the UK, which promote wall-to-wall 'porcelain smiles'. Patients of these clinics all walk away with identical 'ideal' smiles. Firstly, it is statistically impossible that every patient that attends such clinics will require extensive 'smile makeovers'. Secondly, natural beauty lies in diversity, not providing cloned smiles for everyone. Thirdly, in certain circumstances, cosmetic 'rehabilitation' amounts to little more than destruction of healthy teeth for the sake of improving minor imbrications and colour or diastemae closures. Are dentists practising in these clinics respecting professionalism? And what is the reason for providing and marketing these types of procedures?

The reason is sadly opportunistic avarice, exploiting the psychological insecurity and vanity of patients who are ignorant of dental procedures, which can leave them in precarious situations with potential future problems.11 Furthermore, are dentists acting ethically when providing procedures solely for the purpose of enhancement? As mentioned above, cosmetic procedures lie outside professional care, similar to hair salons and beauty parlours. If such care is sought from care individuals, the recipient (patient) should forfeit 'professionalism', and not apply the ethical standards that accompany true therapy. In short, the patient can not have it both ways,ie on the one hand expect fiduciary judgment from a professional, and on the other dictate the treatment they want for non-health reasons. Equally, a dentist providing cosmetic services should also accept that he or she is demoting himself or herself from the status of a professional to a skilled trader such as a hairdresser or tattooist. If this scenario is acceptable for both parties, the outcome is that the patient cannot blame the dentist if things go wrong (since they have forfeited professional ethics which distinguish a professional from a skilled worker), and the dentist can not claim the status of a professional, since they are acting in the interest of business, not in the interest of the patient.

Clinician

As clinicians, dentists have the responsibility of preparing treatment plans that incorporate professionalism (educating the patient) and patient autonomy (respecting patient wishes), and are backed by scientific credence. Furthermore, clinical self-deprecation is essential to ensure that the operator has the ability to perform and deliver what is being proposed. Professionalism has already been discussed above, and the next aspect to elaborate is the scientific rationale for treatment options.

In most of the Western world, keeping up to date with current research and clinical techniques is mandatory for practising dentistry. This involves attending lectures, courses and reading journals relevant to a given speciality. At times, unintentional over-treatment or under-treatment is the result of oblivion or quackery, for example, holistic dentistry which has little, if any, scientific backing. A study by the Department of Health and Social Security in 1986 concluded that although a small number of clinicians intentionally prescribed unnecessary treatment, there was a larger percentage who provided antiquated treatment not based on current scientific advances,12 or performed procedures based on anecdotal rhetoric. Another obscure reason is fakiry, defined as providing an illusory treatment without improving symptoms. A fakir is someone who practices such 'treatment', akin to astrology, palmistry, etc. where blind faith takes precedence over the collective wisdom of science or society.

Many reasons are used to justify cosmetic dentistry, some valid, others spurious. As stated previously, the most commonly requested items are whiter or straighter teeth or closing gaps due to missing teeth. The responsibility of the clinician is to satisfy these requests by suggesting options that are minimally invasive, backed by scientific research, and have acceptable longevity with minimum future complications. It is wise to bear in mind the adage by Pincus,13 one of the godfathers of aesthetic dentistry, when making decisions about a particular course of treatment: 'There is nothing permanent in dentistry.' Adhering to this wisdom, if minimal or least invasive treatment is prescribed the chances of success and longevity are magnified. On the other hand, the more destructive and invasive the treatment, the more inevitable the complications and poor survival rates.

In reality, all treatment options have pros and cons, and ultimately a compromise is reached. This may mean compromising superlative aesthetics for the sake of better function or longer survival rates, which might be a prudent option compared to ephemeral aesthetics and brief longevity. No matter the gains or pains of a specific treatment, it is essential to offer the patient choices, with respective advantages and disadvantages.

A few frequently used excuses to justify purely cosmetic dentistry are as follows:

-

1

Psychological healing

-

2

Abusing the Golden Proportion rule

-

3

Closing buccal corridors

-

4

Achieving optimal occlusal relationships.

This list is not exhaustive, but does highlight some issues that should be addressed before embarking on extensive cosmetic dental procedures.

The excuse of 'psychological healing' is flawed for numerous reasons. Firstly, most dentists are not trained psychologists, and dabbling in psychology is practising beyond the scope of dentistry. Secondly, while the argument is that improving a smile can enhance self-esteem, confidence, emotional state of mind and/or social or career advancements, all these potential benefits are in fact intangible. Are we qualified to assess the emotional make-up of a patient? A brief smile can easily turn into protracted tears if the enhancement procedures fails after a few months or years. Thirdly, many researchers have stated that cosmetic procedures are fads, merely sidetracking or deferring deeper psychological illness. This is analogous to narcotics, which create a transient euphoria but make coping with reality afterwards usually more traumatic.14 Finally, if a dentist is treating a patient purely for improving his or her psychological state of mind, is the patient of sound mind to give informed consent for the cosmetic procedure? Informed consent is only possible if the person (or surrogate) is of sound mind, and is presented with side effects and survival rates (known and disclosed) of the proposed treatment or procedure. Presenting images (either on walls or in a portfolio) showing successful, 'beautiful' outcomes is only conveying one side of the argument. Informed consent is only possible by presenting both sides of the coin.

The next excuse is abusing the Golden Proportion (GP) to justify extensive smile makeovers for achieving 'ideal' beauty. The penchant for the GP is the hobbyhorse of many lecturers who promote cosmetic dentistry. The GP is a framework, not a dogmatic formula or design template for inherent beauty (Fig. 7). If this was the case, all plant and animal species would be clones, which is obviously untrue. The key to beauty is diversity, not monotony of colour, form or the GP. Clinicians and technicians who believe that beauty is only achievable if everything is in the GP are only improving their bank balances, not the dental health of their patients. Furthermore, studies have cited that the maxillary anterior teeth are in the GP in only 17% of the population.15 If one accepts the fallacious argument that the GP is linked to ideal beauty, does it imply that the majority of the population is aesthetically defective? And if so, is plastic surgery or destroying enamel and dentine the only solution for achieving 'ideal' beauty? Or, taking the argument further, is genetic engineering acceptable for creating designer human beings?

Closing the buccal corridor is another misleading argument. The buccal corridor is the bilateral negative spaces during a relaxed smile between the buccal aspect of the teeth and the medial aspect of the lips (Fig. 8). These spaces create a border for the smile composition and are essential for pleasing dental aesthetics. However, some clinicians, who are obsessed with the prominence of teeth and exaggerating the 'white, bright look,' dispel this rationale and argue that these spaces be eliminated. This usually involves prescribing veneers to 'bulk out' the buccal aspects of the premolars (or even molars if these are apparent during smiling), to create a wall-to-wall smile. This is clearly embellishing body parts for little more than subjective beauty, similar to cosmetic make-up. The only difference is that the irreversible damage inflicted on the teeth cannot be washed away the following day with make-up removal cream.

A recent justification for promoting cosmetic dentistry is involving occlusal factors for extensive posterior and anterior restorative work. The scam is as follows: after carrying out a detailed occlusal analysis, the patient is informed of various occlusal problems. These may include deflective contacts, grinding patterns, wear facets, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) clicking etc, and to correct these 'anomalies' an oral rehabilitation is the only answer. Since many clinicians perceive occlusion as esoteric and academic, lecturers of cosmetic dentistry exploit this weakness for the hidden agenda – more veneers and crowns! The flawed logic is that achieving ideal occlusal relationships will resolve occlusal 'problems'. But why solve a problem that does not hurt you? If patients have deflective contacts, grinding patterns, wear facets or TMJ clicking without deleterious clinical finding or symptoms, is more destruction by providing veneers or crowns going to help? Many patients have occlusal eccentricities which they have adapted to and are no worse off. However, clinical intervention could worsen the situation, making the patient occlusally aware of factors to which they were previously oblivious and coped with adequately.

Business

The final role that a dentist has to play is that of a businessman or businesswoman. Often, trying to juggle between what is best for the patient and what is best for the business can be trying and conflicting. Ideally, a professional healthcare provider should consider the interest of the patient as a priority. Nevertheless, the running of a dental practice is expensive and costs must be met for financial viability. There is no doubt that many practices survive by running their daily affairs with bank overdrafts, and if things worsen, it is not difficult to understand why some clinicians may veer towards prescribing extensive or over-treatment in an endeavour to stay afloat. However, when a patient requests whiter or straighter teeth, the immediate response should not be veneers or crowns as a source of revenue. What about bleaching? Or orthodontics? Or composite fillings? Traditionally, these less invasive options are perceived as less lucrative compared to full arch rehabilitations. But these modalities can also be profitable, and more beneficial to the patient. Removing laboratory fees, why can the cost a composite filling not be the same as that for a veneer? Both are equally time consuming, but a direct restoration is obviously less destructive. A change in mind set is necessary if one is to avoid the dichotomy of business vs patient interests. Applying this philosophy overcomes over-treatment for economic gains and helps the clinical welfare of the patient.16

There are a minority of practices which represent the worst case scenarios of marketing by promoting aggressive and over-zealous attitudes to the business of dentistry and are a major contributor to intentional over-treatment.17 Examples include over-claiming on health insurance policies and philosophies such as 'the only treatment for a large defective amalgam is a full coverage crown.' The dentists working in these surgeries usually have blind faith in the spurious teachings of self-styled opinion leaders or cosmetic gurus, delivering entertaining and 'convincing' presentations, all aimed at coercing patients into accepting extensive treatment plans, and in some instances nothing short of charlatanism or fraud.18,19 Other reasons for intentional over-treatment include gaining and elevating personal reputation20 and creating high profile referral practices. These so-called 'specialist' cosmetic dental spas can at times be persuasive and intimidating by exploiting the gullibility and emotional weaknesses of patients. Their ethos is improving profit margins rather than patient health. Profit is a sweet poison – too much is gluttony, while too little is insipid.

What treatment modalities are available for aesthetic dental treatment?

The discussion so far has concentrated on precautions regarding aesthetic dental treatment. However, aesthetic dental care is a burgeoning field and its demand is ever increasing. Patients nowadays expect, or even insist on, treatment outcomes satisfying health, function and aesthetics. Providing care to only alleviate pain or repair damaged tissue is simply not enough. The discerning population aspires to treatment that emulates nature in all aspects. The most frequent request from patients seeking aesthetic dental care is 'Make it white, make it bright, make it right!' To achieve these goals, the clinician has the following modalities to choose from:

-

Bleaching

-

Orthodontics

-

Direct restorations, eg composite fillings

-

Indirect restorations, eg PLV, crowns, Rochette bridges, fixed bridges

-

Implants.

Before embarking on any therapy, written consent and meticulous documentation is essential. As discussed above, consent is only possible once the patient is aware of all the options and has been informed about the pros and cons of each modality. Documentation can be written, photographic, radiographic and image-based. It is paramount to record the baseline before commencing any therapy, for dento-legal reasons and to show what has or has not been achieved by the proposed therapy. In addition, patients often forget what they started with, and showing pre-operative pictures is a wonderful educational tool, as well as showing the vast improvements that are possible with modern dental treatment.21

To satisfy the 'Make it white, make it bright, make it right!' request, a prudent protocol is to start with the least invasive procedure and progress to the most complicated or involved therapy. Bleaching is an excellent starting point, it is innocuous, effective, predicable, economical, and for many is sufficient to achieve the desired result (Figs 9 and 10).

Similar to bleaching, orthodontics is minimally invasive and should be considered the first line of treatment for crowding and closing spaces. It is also ideal for cases where a tooth of hopeless prognosis requires extraction before implant placement. In these circumstances, and if the clinical situation is conducive, rapid orthodontic extrusion is an ideal method for 'gaining' coronal bone by moving the dentogingival complex in a coronal direction. Another use is creating space for pontics or implants, or up-righting roots to facilitate implant placement (Fig. 11). However, there are limitations to orthodontic treatment and compliance can be poor or totally rejected by the patient. Firstly, unsightly brackets can be embarrassing and secondly, long-term retention is essential to prevent relapse. Opting for lingual orthodontics can circumvent the former, and the latter can be fulfilled by using permanent retention with retaining wires with resin filling materials. Another point that may deter patients from seeking an orthodontic approach is the protracted treatment time and regular monitoring visits.

While bleaching and orthodontics make teeth whiter and straighter, they do little to compensate for tooth loss due to wear. In these circumstances, other possibilities need to be explored. To resolve non-carious tooth loss by attrition, abrasion, and erosion requires restorative intervention. The choices are either a direct or indirect approach. The direct route is expedient, but requires a degree of knowledge, skill and patience. Superb results are possible with modern composite resin fillings using dentine bonding agents. The key requirements are a working knowledge of the concerned dental materials and adherence to strict isolation protocols such as using rubber dam, which is mandatory for successful and long lasting results. Isolation is applicable for both anterior as well as posterior restorations, particularly if amalgam restorations are being replaced with tooth coloured 'white' fillings (Fig. 12).

The indirect options are PLV, inlays, onlays, crowns or bridges. Once again, a working knowledge of materials is crucial, together with appropriate clinical training, preferably 'hands-on' courses to ensure predictable and lasting outcomes. This applies equally to the ceramist fabricating the restorations. As with any aesthetic treatment, PLV, crowns or bridges are all open to abuse. The correct use of any restoration is to replace lost tooth substrate, not to create a contrived smile based on the Golden Proportion. PLVs in particular are very predictable and successful restorations so long as they are delivered using the correct materials, employing a skilled ceramist, and performed by an experienced operator (Fig. 13). The dental literature cites numerous studies, both in vitro and in vivo trials, affirming the success of PLVs and rating them as one of the most predictable of all indirect restorations.

Aesthetic crowns are usually all-ceramic units using a variety of porcelains (Figs 14 and 15). The crucial factor for success is choosing the appropriate ceramic for the prevailing clinical findings. Nearly every month sees the launch of a new ceramic system on the market, each claiming benefits over existing rivals, adding to confusion and often making decisions perplexing and daunting. This is another reason that the clinician should cut through the hype and furnish him or herself with scientific facts pertaining to a given ceramic. One of the most promising ceramics is zirconia, which is used for implant abutments as well as for single and multiple unit prostheses. However, as with any new material, long-term clinical performance is essential to substantiate manufacturers' claims. In addition, it is advisable to inform patients about these relatively novel materials in case the restoration does not live up to, or meet anticipated expectations (Fig. 16).

Post-operative photo of patient in Figure 13, showing four all-ceramic crowns on the laterals and canines to restore health, function and aesthetics

The last treatment modality to consider is dental implants. There is no question that implants are the current 'hot topic' in dentistry and judging by the innumerable courses, articles and promotional materials, many clinicians are joining the band wagon for fear of being left behind. In addition, success with fixtures has vastly increased over the last four decades and excellent results are possible when replacing missing teeth. However, unlike bleaching, a weekend course held at an airport hotel is insufficient for adopting implants as a routine treatment in general practice. More than any other dental discipline, adequate training and mentoring cannot be overstated. While many manufacturers portray a simplistic, almost 'taken for granted approach' for placing fixtures, the clinical reality is far different. If treatment goes according to plan, it gives a false sense of security and confidence to the novice. It is only when plans fail and treatment complications occur that a reality check hits home. Experience can not be substituted for chance successes. If one is considering incorporating implants as part of aesthetic treatment, the best method is obtaining recognised diplomas or degrees at reputable teaching institutes, followed by hands-on experience and a period of mentoring. Although this may seem laborious, the fruits of these labours will be invaluable when embarking on implant therapy and the practitioner will avoid many pitfalls by learning from colleagues who have undergone and overcome mistakes. The onus is on the clinical: the more knowledge and experience, the better the quality of care one can offer patients, with enhanced clinical satisfaction.

Conclusion

At times it is challenging, or impossible, to reconcile commerce values with professional virtues, or paternalism and patient autonomy. However, ethics should take precedence over fiscal concerns. Similarly, patient autonomy is not paramount compared to patients' health. For example, euthanasia may be consented, but is nevertheless a criminal offence. But in our current vogue conscious society, health professions may be forced to concede that ameliorating health and function is insufficient, and that enhancement encompasses our 'healing' services. Feeling healthier may be less important than looking better.

As a concluding comment, we may be approaching an abyss and opening the doors to a 'brave new world' where health is derisory, and enhancement laudable – perhaps at our peril.

References

Sheets C G . Modern dentistry and the esthetically aware patient. J Am Dent Assoc 1987; Spec No: 103E–105E.

Ahmad I . Protocols for predictable aesthetic dental restorations. Oxford: Blackwell Munksgaard, 2006.

Goldstein R E, Lancaster J S . Survey of patient attitudes towards current esthetic procedures. J Prosthet Dent 1984; 52: 775–780.

Ahmad I . A clinical guide to anterior dental aesethics. London: BDJ Books, 2005.

Sheets C G, Levinson N . Psychodynamic factors contributing to esthetic dental failures. Compendium 1993; 14: 1610–1620.

Welie J V M . Do you have a healthy smile? Med Health Care Philos 1999; 2: 169–180.

Jenson L . Restoration and enhancement: is cosmetic dentistry ethical? J Am Coll Dent 2005; 72(4): 48–53.

Chiodo G T, Tolle S W . Cosmetic treatment, autonomy, and risks: “if you don't do it, I'll go to a dentist who will”. Gen Dent 2001; 49: 16–22.

Hussey D L . Where is the ethics in aesthetic dentistry? Br Dent J 2002; 192: 356.

Ozar D T, Sokol D J . Dental ethics at chairside: professional principles and practical applications. 2nd ed. Washington DC: Georgetown University Press, 2002.

Mulcahy D F . Cosmetic dentistry: is it really health care? J Can Dent Assoc 2000; 66: 86–87.

Schanschieff S G, Shovelton D S, Toulmin J K . Report of the Committee of Inquiry into Unnecessary Dental Treatment. London: HMSO, 1986.

Pincus C L . Cosmetics – the psychologic fourth dimension in full mouth rehabilitation. Dent Clin North Am 1967; Mar: 71–88.

Ringel E W . The morality of cosmetic surgery for aging. Arch Dermatol 1998; 134: 427–431.

Ward D H . Proportional smile design using the recurring esthetic (RED) proportion. Dent Clin North Am 2001; 45: 143–154.

Hartshorne J, Hasegawa T K Jr. Overservicing in dental practice – ethical perspectives. SADJ 2003; 58: 364–369.

Glick K . Cosmetic dentistry is still dentistry. J Can Dent Assoc 2000; 66: 88–89.

Kelleher M . Makeover myths from the “Land of the Fee”. Oral presentation given at the British Dental Association Conference and Exhibition 2007. 24-26 May 2007, Harrogate, UK.

Besford J . Western approaches: corrosive perfectionism from North America. Oral presentation given at the British Dental Association Conference and Exhibition 2007. 24-26 May 2007, Harrogate, UK.

Chambers D W . Quackery and fraud: understanding the ethical issues and responding. J Am Coll Dent 2003; 70: 9–17.

Ahmad I . Digital and conventional dental photography: a practical clinical manual. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing Co, 2004.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmad, I. Risk management in clinical practice. Part 5. Ethical considerations for dental enhancement procedures. Br Dent J 209, 207–214 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.769

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.769

This article is cited by

-

Why simple aesthetic dental treatment in general practice does not make all patients happy

British Dental Journal (2014)