Key Points

-

There is a distinct lack of knowledge of the clinical remit of this group of dental care professionals.

-

Dentists should be informed about the substantial contribution hygienist-therapists could make to patient care.

-

Dentists working in larger practices who already employed a hygienist or vocational trainee were more positive in their view of hygienist-therapists.

Abstract

Aims Recent UK legislation allows dental therapists or jointly-qualified dental hygienist-therapists to work in the general dental service. This study aimed to investigate the extent of dentists' knowledge of the clinical remit of jointly qualified hygienist-therapists, their willingness to consider employing such a professional, and factors associated with these two measures.

Materials and methods A postal questionnaire was sent to 616 NHS-registered dentists in South-East Scotland. Analysis and classification of responses to open-ended questions used standard non-parametric statistical tests and quantitative techniques.

Results Following two mailings, a 50% (n = 310) response rate was obtained. A total of 65% of dentists worked in a practice employing a dental hygienist, while only 2% employed a dental therapist. Hygienists tended to work in larger practices. Dentists' knowledge of the clinical remit of the dually-qualified hygienist-therapist was found to be limited, reflecting a restricted and inaccurate view of the professional remit of a hygienist-therapist. The majority (64%) said they would consider employing a hygienist-therapist in their practice, rising to 72% amongst dentists already working with a hygienist. Reasons given by dentists who were negative about this prospect were sought. Those who worked with a hygienist tended to refer to lack of physical space, whilst those who did not tended to cite reservations on clinical skills, competence and responsibilities, or on the costs involved.

Conclusions This study identified considerable ignorance and negativity among dentists about the nature and clinical remit of this group of professionals. Dually-qualified hygienist-therapists will be in a position to treat much of the routine disease that exists within the population, and dentists may benefit from education in relation to the substantial contribution these individuals could potentially make to patient care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1983 the first integrated hygienist-therapist training course began in London, although Scotland only commenced its first programme leading to a dual qualification in October, 2003. This course extends over 27 months, and the General Dental Council (GDC) permits dually-qualified hygienist-therapists to undertake comprehensive periodontal therapy, preventive care and restorative procedures for both the child and adult population. In terms of restorative work, they may carry out direct restorative procedures not involving the adult pulp. At the present time, all procedures may only be undertaken following a written prescription from a registered dentist.

Although hygienists commonly work in general dental practice,1 legislation passed in 2002 now permits dental therapists to also be employed in this setting. Given the clinical remit of dually-qualified hygienist-therapists, their contribution to the treatment of disease and maintenance of oral health in the population could be enormous. The shortage of dentists in the UK could be resolved through the appropriate use of these new oral healthcare workers. However, the full benefit of dually-qualified hygienist-therapists will only be obtained if they are supported by the dental profession as a whole.

Aim

This study was undertaken to determine the knowledge of a sample of general dental practitioners regarding the clinical remit of dually-trained hygienist-therapists, ascertain the acceptability of these personnel into the general dental service in Scotland, and to identify factors associated with these two measures.

Materials and methods

All practitioners in four Health Board areas in the South-East of Scotland (Lothian, Borders, Fife, Forth Valley) were selected for inclusion in this study. A total of 616 dentists (approximately one third of the total working in Scotland) were identified via the Practitioner Services Division (NHS Scotland), and questionnaires were mailed to their practice addresses. Following two mailings, 310 (50%) questionnaires were returned and subsequently analysed. Questionnaires were formulated to determine respondents' knowledge through a series of 16 questions about the clinical remit of a hygienist-therapist, with a response set of 'Yes', 'No' or 'Don't know', which was summed to obtain a knowledge score (range 0-16). Acceptability of the hygienist-therapist role was measured by a yes/no question as to whether the dentist would consider their employment in their practice, with a follow-up for those responding negatively to seek their reasons. The questionnaire also included a number of 'open' sections where personal comments were invited.

Statistical analysis of factors associated with knowledge and acceptability used standard non-parametric statistical techniques (Chi-square, Mann-Whitney test, Spearman R). Responses to open-ended questions regarding reasons why dentists would not consider employing a hygienist-therapist were examined for dominant themes, which were then classified into a number of types of responses.

Results

Results are based on individual responses from each practitioner. A total of 31% (n = 97) of respondents were female. The mean number of years since GDC registration was 19.7, range 4 to 43 (missing: 37).

Section A: practice details

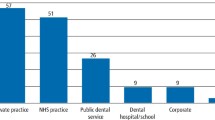

a) NHS/private practice

Dentists were asked whether they worked in an NHS, private or mixed practice. Only 3% (n = 8) of respondents worked exclusively in private practice, with the majority of the remainder (55%; n = 166) working in mixed practices, and 42% (n = 128) stating they worked in NHS practices (missing: 8).

b) Number of dentists and surgeries in each practice

The median number of dentists working in each practice was three, range 1 – 10 (Fig. 1). The number of dentists compared to the number of surgeries per practice is illustrated in Figure 2.

As Figure 2 demonstrates, for 44% (n = 136) of respondents, the number of dentists in their practice equalled the number of surgeries; for 20% (n = 60), there were fewer surgeries than dentists, and for 35% (n = 106), there were more surgeries than dentists in the practice. The situation where there were fewer surgeries than dentists was confined to practices of three or more dentists. Availability of surgery capacity is of obvious relevance to the consideration of employment of a hygienist-therapist.

c) Practices with dental hygienists, therapists, associates and vocational trainees (VTs)

A total of 65% (n = 202) reported the employment of a hygienist (missing: 3%; n = 8), including 23% (n = 67) who said that more than one was employed. Only 2% (n = 7) reported the employment of a dental therapist (missing: 2%; n = 7). Seventy-three percent (n = 224) said that their practice employed associates (missing: 3%; n = 10), and 22% (n = 67) that their practice supported VTs (missing: 4%; n = 12). Hygienists, associates and VTs were all more likely to be found in larger practices. For example, only 31% (n = 11) of single handed and 51% (n = 33) of two handed practices employed a hygienist, compared with 88% (n = 52) of four handed and 86% (n = 55) of five handed practices.

Section B

a) Dentists' knowledge of the clinical remit of hygienist-therapists

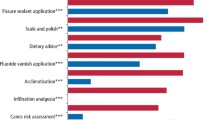

Responses to each of the 16 questions covering clinical remit are detailed in Table 1.

Just over half (52%) of responding dentists considered that the following six procedures were within the clinical remit: placing temporary fillings, re-cementing crowns, restoring deciduous teeth, undertaking multiple surface restorations in deciduous teeth, taking impressions, and administering inferior dental block analgesia. Only 25% of dentists correctly considered that a hygienist-therapist could undertake multiple surface restorations in permanent teeth or treat patients under conscious sedation. Most respondents (60%) incorrectly believed that a hygienist-therapist could only treat patients if the dentist was on the premises.

b) Predictors of dentists' knowledge of hygienist-therapists' remit

Responses to the series of knowledge questions were summed to give a score (0-16) reflecting knowledge of the hygienist-therapist clinical remit. The mean score was 10.1 (64% correct), with a standard deviation of 3.27, range of 1-16. Table 2 illustrates the results of tests of association (Spearman R for interval order variables, Mann-Whitney test for dichotomous variables) for potential predictors of knowledge score.

Table 2 demonstrates that knowledge was significantly higher amongst male dentists, dentists who worked in VT practices, in mixed or private practices, or in practices already employing a hygienist.

c) Acceptability of hygienist-therapists as practice employees

Dentists were asked if they would consider employing a hygienist-therapist in their practice. Ten subjects declined to answer on the grounds that they were not a principal, and another 13 did not respond. Of the remaining 287, 64% (n = 183) replied they would, 30% (n = 90) said they would not and 4% (n = 14) said they did not know or were undecided. Table 3 illustrates the results of tests of association (Mann-Whitney test for interval order variables, Chi square test for dichotomous variables) for potential predictors of willingness to employ a jointly qualified hygienist-therapist.

A logistic regression of these variables against positive response on employment of hygienist-therapists confirmed that working in a practice which already employed a hygienist or therapist, more accurate knowledge of the hygienist-therapist remit, and working in a practice with more dentists were the most important predictors of a positive response. These variables predict a positive response in 84% and a negative response in 44% of cases (overall prediction: 69%; model Χ2 = 25.93, df = 3, p = 0.001).

The 104 dentists who said they would not employ a hygienist-therapist or that 'it depends', were invited to give open-ended reasons for their response. Ninety-one gave useable responses. As the interpretation of the question may have been influenced by the experience of working with a hygienist, Table 4 shows these responses, which are grouped into five categories, separately for those in practices currently employing a hygienist and for those in practices who did not.

The most common reason given by dentists in non-hygienist-employing practices was concern over clinical skills, responsibilities or patient preferences. These concerns were not in general shared by dentists in hygienist-employing practices, whose most common reservation was lack of physical space.

Below is a selection of verbatim comments illustrating these categories:

-

Space:

-

'I would love to, but only have one surgery and it is in full use.'

-

'Probably not, due to lack of space. It may be possible in a part-time capacity to give me time for CPD etc.'

-

'No, as only one surgery available and with five dentists, all surgery time is needed for scale/polish/periodontal care.'

-

-

Clinical skills, responsibilities:

-

'No - the person would encroach/be in competition with the GDP.'

-

'Not sure who would be responsible for treatment carried out? If they are responsible for their own treatment, then perhaps.'

-

'No, don't feel that they have had sufficient training, as to become qualified as a dentist takes 5 years!'

-

'If things go wrong then the dentist has to mop up. We need more dentists, NOT PCDs. The workforce planning committees are dodging the issue and going for a cheaper, poorer quality option.'

-

-

Costs:

-

'No, and the reason is simple. I am unsure of the financial implications to the practice. If hygienist-therapist is salaried and I am pricing by piecework rather than salary, and her work remunerates on piecework, how do I know that I can afford her?'

-

'Current fees make the business case difficult.'

-

'Not at present, difficult to see where funding would be available under poor NHS remuneration.'

-

-

Demand:

-

'Not enough workload.'

-

'No children patients.'

-

'As both practitioners are over 60, the patient base is not expanding and is not considering new staff.'

-

d) Benefits of employing a hygienist-therapist in general dental practice

Respondents were invited to state whether these personnel would have a useful contribution to make in practice. Of those who replied (n = 289, 93%), 85% (n = 245) felt they would, 10% (n = 29) said they would not and 2% (n = 7) stated they would possibly be useful. Almost identical proportions of those in hygienist-employing practices and those who were not, gave a positive response to this question.

e) Salary scales for hygienist-therapists

Dentists were asked to suggest an appropriate annual salary for hygienist-therapists. Nearly half (46%; n = 135) opted for the salary range £20-24,000 pa, with a further 23% (n = 68) suggesting £16-19,000 pa and 19% (n = 56) £25-29,000 pa.

General comments

A final open section was included to allow dentists to make general comments about any aspect of hygienist-therapists, again evoking several discussion points.

Positive comments: the first six comments point out the advantages of the complementary role that could be played by the hygienist-therapist.

-

'Due to the acute shortage of dentists, this avenue should be developed as quickly as possible'

-

'Hygienist-therapists will go a little way to solving the desperate shortage of qualified dentists in Scotland'

-

'Given the increased pressure on NHS dentists, a hygienist-therapist could provide additional support and relieve patient waiting lists'

-

'Always in favour of this approach. Well-trained motivated people can perform work which dentists do routinely – would allow dentist to improve skills needed for more demanding, time-consuming work'

-

'May encourage more dentists to specialise if relieved of a lot of routine work'

-

'Principals could have a larger list and refer simple treatments to hygienist-therapist'

-

'Many dentists need to be educated to embrace this qualification, and not see it as a threat'

-

'I would like my existing hygienist to become dually qualified'

-

'Roll on the day!'

-

'Sounds a very good idea'

-

'The sooner the better to address the deteriorating condition of the population's dental health'

-

'Would work well in community or areas where there are no NHS GDPs'

-

'Would make general practice more efficient and provide a better service to the patient.'

Negative comments: Many negative comments refer to misgivings about skills and professional competence, economic costs, and acceptability to patients. Several insisted that such a role should be limited to work in the community, and that the solution was to train more dentists rather than developing a complementary profession.

-

'Not confident to let these people work without supervision'

-

'Don't wish to delegate treatment of children to someone else'

-

'More difficult to maintain standards with shorter training'

-

'Would not support independent practice'

-

'How can a dentist cope with added responsibility and having to make clinical judgements on behalf of someone else?'

-

'Dentistry stressful and difficult enough job for people with a much more comprehensive training and higher intellectual ability'

-

'Clinical output would be lower than a dentist's with the same surgery costs'

-

'May not be able to afford them as they would have to be paid as an associate'

-

'Who pays when replacements are needed for the therapists' mistakes when the patient would rather see a dentist?'

-

'Introduction of this group generally a bad move – current hygienist cannot make enough money to pay for her own salary or make a decent profit'

-

'Not enough research into patients' acceptance of a seemingly less qualified operative carrying out treatment'

-

'Long-term patients may view the hygienist-therapist as a less skilled operator, and refuse to attend'

-

'Public will find it impossible to distinguish between dentists and hygienist-therapists'

-

'Patients may consider it inappropriate that a GDP is not providing these services but they still pay the full fee'

-

'Should be employed by the Community Dental Service to accompany community dentists to schools and villages in a mobile unit'

-

'Keep them in the community'

-

'Best use would be in the community setting'

-

'Should only be employed in community or hospital services, under strict supervision'

-

'[This is a] Cheap, easy option to address manpower crisis. [We] need a third dental school in Scotland'

-

'If they want to become dentists, they should go through conventional routes'

-

'Just train more dentists'

-

'Should be more resources spent on producing dentists'

-

'How many hygienists want this? Hygienists are mainly part-time, female and not interested in more training'

-

'Being hi-jacked by academics and theorists!'

Other comments

-

'Dually-qualified people should have their own NHS list number'

-

'Nursing qualifications should count heavily in entrance requirements'

-

'I am ignorant about what they can and cannot do'

-

'They should be able to undertake semi-reversible procedures, eg making and fitting temporary crowns'

-

'Training should be rigorous and externally validated.'

Discussion

Knowledge and acceptability of hygienist-therapist employment were greater amongst dentists working in larger practices, or those employing additional personnel such as associates, VTs or hygienists.

Knowledge of the hygienist-therapist remit

A number of dentists were vague about the remit of this group. High numbers of respondents gave accurate answers in relation to the clinical remit in terms of children, but not in terms of adults. These findings of lack of knowledge agree with those of Gallagher and Wright.2

Only 25% of respondents knew that dually-qualified personnel are legally able to undertake multi-surface restorations in the adult dentition, with 48% being aware of their ability to use composite materials in restorative procedures. Although 73% were aware that hygienist-therapists could administer inferior dental block analgesia, the fact that 28% were not is surprising, given this has been permitted since 2002. More generally, 60% of respondents were incorrect in their view that a hygienist-therapist was only able to treat patients if a dentist were on the premises.

Acceptability of the hygienist-therapist role

Almost two-thirds of responding dentists said they would consider employing a dually-qualified hygienist-therapist. This is greater than reported by Gallagher and Wright2 but, as those authors admit, such responses may not truly reflect the extent of dentists' reservations.

Acceptability was higher among dentists who were working with a hygienist, who were more aware of the hygienist-therapist remit, and who were part of a larger team. Comments from those who would not consider their employment indicated that potential barriers were space, costs, and concerns about clinical roles and responsibilities (Table 4).

Open-ended comments made by dentists give a more detailed picture of the nature of their reservations. Ignorance, perhaps due in part to unfamiliarity with working with hygienists, may account for a degree of suspicion about their ability to undertake procedures which historically have been in the domain of the dentist. This suspicion, which we believe is unfounded, is reflected in comments which hint that jointly qualified hygienist-therapists would be a threat to the dental profession. In a time when NHS dentistry has become almost impossible to access in many areas, this group of clinicians should be welcomed as another source of clinical expertise, well able to deal with the bulk of routine dentistry in the UK.

Another concern was that the public would be unable to distinguish between dentists and hygienist-therapists, although we are not clear why this is relevant. The public needs to be informed of the emergence of this professional group, and dentists reassured that quality of care will not suffer. We believe acceptance would be improved if the hygienist-therapist had a new title, and suggest that 'Oral Health Practitioner' could be appropriate. This would recognise their broader training and education, allowing both the profession and public to differentiate between members of the dental team.

Such negativity was not universal: several dentists thought that hygienist-therapists would have a positive contribution to make. The fact that two-thirds of dentists were favourably disposed to employing a hygienist-therapist in their practice provides some encouragement.

Funding change

A number of relevant issues were raised pertaining to remuneration for additional staff. Perhaps dentistry should adopt the system utilised by medicine, where staff are not paid directly by the doctor but from a monetary allocation to the practice from the NHS. Alternatively, dental centres could be built in areas of need where a number of hygienist-therapists could be employed, receiving referrals from GDPs. Medicine has developed to the extent of now having nurse specialists and consultants and indeed, in more remote and rural areas of the country, much of routine medical care is undertaken by nurse practitioners who have received appropriate education and training.

Training and clinical competence

A comparison between undergraduate teaching and that of hygienist-therapists in terms of clinical training demonstrates that the number of operative techniques hours (phantom head) and potential patient treatment hours are remarkably similar. It is accepted that following the new curriculum, 'The first five years', clinical ability is measured by competence, but this is difficult to assess without having a basis of expected time-periods taken to become competent.3 In terms of the restorative component of this education, it should be remembered that the potential number of hours of clinical teaching and supervision is restricted to certain areas of restorative work, where more advanced procedures are not addressed. Therefore, it is probable that hygienist-therapists could have more experience of particular procedures than undergraduates. The parallel exists in periodontal training in the hygiene-therapy course, where the time devoted is much greater than in the undergraduate dental curriculum.

Quality of care, not historically who delivers it, should be at the forefront of the minds of those responsible for the delivery of dental services in the UK. Unless alternative avenues are explored in the provision and funding of oral healthcare, dental services are likely to remain inadequate. This is particularly so in Scotland, where the incidence and prevalence of disease is much higher than the remainder of the UK, specifically in the socially and dentally deprived.4

Conclusions

The provision of oral care for the UK population is destined to change, and although advancements have been made recently, it is likely that further developments will take place. The oral health of the population is at stake and, in terms of a disease which is by-and-large preventable, consideration should be given to emerging new groups of individuals, such as hygienist-therapists, who have a substantial contribution to make. Their role could be increased further if other restrictions were removed from their clinical practice.

The hygienist-therapist may be well received by patients and dental workforce planners but, given their current need to work to a dentist's prescription, their acceptance by dentists is critical. It is apparent that significant education of dentists is necessary, and hygienist-therapists are likely to require substantial central support to be accepted in general dental practice.

Summary

-

1

General dental practitioners have only partial knowledge of the clinical remit of dually-qualified hygienist-therapists.

-

2

Dentists' knowledge and attitudes are positively influenced by working in a practice where a hygienist is already employed.

-

3

While most dentists agreed they would consider employing a dually-qualified hygienist-therapist in their practice, the large number of negative comments offered indicate that considerable barriers exist which may make this desirable goal difficult to achieve.

References

Ross M K, Ibbetson R J, Rennie J S . Educational needs and employment status of Scottish dental hygienists. Br Dent J 2005; 198: 105–109.

Gallagher J L, Wright D A . General dental practitioners' knowledge of and attitudes towards the employment of dental therapists in general dental practice. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 37–41.

The first five years. The undergraduate dental curriculum. London: General Dental Council, 1997.

Modernising NHS dental services in Scotland: consultation. Scottish Executive, 2003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ross, M., Ibbetson, R. & Turner, S. The acceptability of dually-qualified dental hygienist-therapists to general dental practitioners in South-East Scotland. Br Dent J 202, E8 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2007.45

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2007.45

This article is cited by

-

Expert view: Steve Turner

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

The perceptions and attitudes of qualified dental therapists towards a diagnostic role in the provision of paediatric dental care

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

Development and retention of the dental workforce: findings from a regional workforce survey and symposium in England

BMC Health Services Research (2020)

-

The role of dental hygienists and therapists in paediatric oral healthcare in Scotland

British Dental Journal (2020)

-

The role of dental hygienists and therapists in paediatric oral healthcare in Scotland

BDJ Team (2020)