Key Points

-

More and more people are retaining their teeth into old age. This paper examines the findings of a number of large studies which have followed older people over time in order to examine the natural history of dental caries in that age group.

-

Surprisingly, the dental decay rate over time among older people is at least as great as that among adolescents.

-

Interventions aimed at improving the oral health of older people should take into account and use a broad combination of clinical and population-based strategies, as there is no 'magic bullet' which will eliminate the problem.

Abstract

Background Little was known of the natural history of dental caries among older adults until recently, but reports from a number of large cohort studies have now enabled better understanding of the nature and determinants of dental caries in older people. The aim of this review is to examine and compare findings from established population-based longitudinal studies of older adults in order to determine their preventive implications.

Methods The dental literature was reviewed in order to identify reports on dental caries incidence from large, population-based dental longitudinal studies of older adults (age 50+) with at least 3 years of follow-up.

Results Reports were identified from four studies (in Iowa, North Carolina, Ontario and South Australia) which met the criteria; four reports dealt with coronal caries, and five with root surface caries. When annualised, coronal and root surface caries increments were combined and compared with those reported for adolescents, the caries experience of older people over time (between 0.8 and 1.2 new surfaces affected per year) exceeded that reported from cohort studies of adolescents (between 0.4 and 1.2 surfaces per year). The only caries risk factor common to all four studies was the wearing of a partial denture (for root surface caries only).

Conclusions Older people are a caries-active group, experiencing new disease at a rate which is at least as great as that of adolescents.

Practice implications Dentate older people should be the target of intensive monitoring and preventive efforts at both the clinical practice and public health levels. There is no easily identifable 'magic bullet' for preventing caries in that age group, but the use of evidence-based preventive interventions (such as fluoride) should suffice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

As well as undergoing a demographic transition, whereby the number and proportion of older people in the population are increasing steadily,1 industrialised countries are also undergoing a 'dental transition', marked by a steady reduction in edentulism and missing teeth among older people.2 The dental profession is now faced with the challenges of treating and preventing dental caries in an age group in which little is known or understood of the disease. Moreover, there is a perception among dental professionals and policy-makers that dental caries is, for the most part, only active in younger people.3 Over a decade ago, a clear need was identified for information on the natural history of dental caries among older people,4,5 in order to provide clarification of issues such as: (a) whether root surface caries is, in fact, the predominant form of caries experienced; (b) whether coronal caries increments continue in dentitions which are already heavily restored; and (c) the nature and timing of possible interventions to prevent those diseases or arrest their progression.

Studying the natural history of chronic, progressive diseases such as dental caries, requires the use of the longitudinal study design, whereby repeated examinations are made on the same individuals over time. It also requires that the people being studied have been randomly selected from the general population; findings from studies involving samples of dental patients (termed 'clinical convenience samples') may not necessarily be generalisable, because people who are regular users of dental care tend to differ in several important respects from those who are not.6

In recent years, a number of reports have appeared from dental longitudinal studies ('cohort studies') of population-based samples of older people, and these are making a substantial contribution to our knowledge of the natural history of dental caries in that age group. The aim of this brief review is to examine and compare the findings of those studies in order to consolidate our current knowledge of the natural history of dental caries among older people.

Methods

The MEDLINE bibliographic database was searched (via Ovid and PubMed) for eligible studies using the key terms 'aged', 'dental caries' and 'cohort studies'. The searches were repeated substituting, in turn, 'follow-up studies', 'longitudinal studies' and 'prospective studies' for the term 'cohort studies'. The EMBASE bibliographic database was searched in the same manner. The reports obtained in this way were further limited by applying the following criteria for inclusion:

-

1

They had to have been published in English

-

2

Participants had to be at least 50 years old and number at least 500 at baseline (for reasons of statistical efficiency)

-

3

A probability-based population sample was used, rather than a convenience or clinical sample (in order to be able to generalise from the study estimates)

-

4

Data were reported separately for both the incidence and increment of both coronal and root surface caries, and

-

5

The observation period was at least 3 years, considered to be the minimum length of follow-up time for (a) sufficient disease experience to be observed, and for (b) satisfactory elucidation of risk factors.

In addition, the databases were searched again using the names of the authors of the papers identified in the first search, after which the same criteria were applied. Baseline data from the studies concerned were obtained in the same manner.

In the second part of the study, the identified reports were scrutinised for evidence of multivariate modelling of caries occurrence, in order to identify common risk markers and risk factors which might provide a convenient focus for preventive interventions.

Results

The MEDLINE search via Ovid resulted in 45 'hits', while that via the PubMed search using the same keywords resulted in 324. The EMBASE search retrieved none. From those reports, dental longitudinal studies of older people in Iowa, North Carolina, Ontario and South Australia were identified which met the entry criteria for this study (extending the searches substituting, in turn, 'follow-up studies', 'longitudinal studies' and 'prospective studies' for the term 'cohort studies' resulted in no further studies being found which met those criteria). There were seven reports identified from those included in the current study, of which two described coronal caries,7,8 three described root surface caries,9,10,11 and two presented data on both types of caries.12,13 All but two of the reports described changes over 3 years; the remaining two covered a 5-year period.9,13

A summary of the baseline estimates for caries prevalence and severity from earlier reports in the Iowa,14 North Carolina,15 Ontario16 and South Australian17 studies is presented in Table 1. Overall, the dental characteristics at baseline were quite similar, with the notable exception of the North Carolina blacks, who had (on average) fewer teeth present and lower caries experience.

A summary of the caries incidence and increment estimates from the studies is presented in Table 2. In order to enable calculation of a combined caries increment and facilitate comparison with the other studies, the five-year report from the North Carolina study9 is not included in the table; however, the South Australian study13 is included because it reported data on both coronal and root surface caries. Estimates were reported separately for blacks and whites in the North Carolina (NC) study.

The incidence estimate is the proportion of participants who experienced new caries in one or more surfaces during the observation period, while the increment is the mean number of surfaces which were affected. Thus, in the Iowa study, 56% of participants had one or more coronal surfaces affected by caries during the three years, with a mean 2.4 surfaces affected.

Reported 3-year coronal caries incidence ranged from 45% to 59%, with a mean increment of between 0.5 and 0.8 surfaces per year. The coronal caries estimates from the North American studies were similar (with the exception of the NC blacks), and, while the longer period covered by the South Australian (SA) study makes direct comparison difficult, the rates appear to be consistent. The lower increment observed among the NC blacks may be at least partly accounted for by their greater reported incidence of tooth loss.18

There was more variation in the incidence estimates for root surface caries, with between 29% and 44% of individuals experiencing new disease over a 3-year period. The mean increment ranged from 0.2 to 0.4 surfaces per year. For all studies, the contribution of coronal caries to the combined increment was greater, ranging from just over half (in the SA study) to three-quarters (in the Ontario study).

Predictors of caries over time

Multivariate modelling of caries occurrence had been reported from three of the cohort studies (NC, Ontario and SA), and had been done for both coronal7,8,13 and root surface10,11,13 caries. The outcomes of those models are summarised in Table 3. Partial denture wearing was a predictor for root surface caries for every group except the NC whites. No other common risk factor was found.

Discussion

Caries incidence data from five different large-scale, longitudinal studies have been reviewed and found to be remarkably consistent in their findings. The data suggest that older people are indeed a caries-active group. While both coronal and root surface caries contributed to the observed increments, there was a consistent pattern whereby coronal caries made the greater contribution to the overall increment. Clinical preventive measures for older people should clearly be directed at both types of caries, as the widespread perception that root surface caries is their only problem is erroneous.

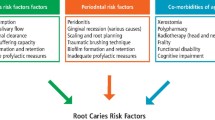

The only caries risk factor common to all four studies was the wearing of a partial denture, and that was for root surface caries only (and it did not emerge as a risk factor among NC whites). Partial dentures have been previously identified as being associated with greater root surface caries experience in a cross-sectional study;19 it is unclear whether this is due to their having a role in causing the disease, or whether it merely reflects the higher disease rate which led to wearers losing teeth in the first place. However, the consistency of the finding across the longitudinal studies means that partial denture wearers should be the target of intensive clinical preventive efforts. Other than partial dentures, no single characteristic or behaviour was uncovered which would be easily amenable to change through intervention at either the clinical or public health levels, indicating that population-based approaches to preventing caries (such as water fluoridation) are as appropriate for older people as they are for children and adolescents.20 However, it is possible that differences in approach may also have limited the extent to which the studies unearthed risk factors. For example, the primary focus of the South Australian report14 was the role of medications as putative risk factors for dental caries, while that of the North Carolina study8 was the relationship of ethnicity and caries risk.

It is worthwhile to investigate how the observed increments compare with those reported for adolescents. Older people may be considered to be even more at risk than children and adolescents because root surface caries can also contribute to their caries increment, whereas it is extremely uncommon among individuals under 20 years of age.21 In Figure 1, , the annualised combined caries increments from the reviewed studies have been plotted against annualised data available from longitudinal studies of adolescents which have reported caries increments from: age 12 to 15 among 655 Swedes;22 age 12 to 15 among 583 Finns;23 and age 15 to 18 among 690 New Zealanders.24 That the caries experience of older people over time was at least as great as that of adolescents should provide considerable food for thought, given Western industrialised countries' concentration of dental public health, clinical and preventive resources upon children and adolescents, rather than older people.25

It is possible (but not probable) that the decision to limit the literature search to MEDLINE, PubMed and articles in English may have resulted in the omission of studies which should have been included. This is unlikely, however, given (a) the status of English as the lingua franca of science, and (b) the relative rarity of observational cohort studies of the oral health of older people.

In summary, review of the published outcomes of recent large cohort studies shows that older people are a caries-active group, with coronal caries making the major contribution to ongoing disease experience. No single, over-arching risk factor for caries among older people has been identified, emphasising the need for multi-strategy preventive efforts, including the use of fluorides in both population- and individual-level prevention.

References

Berkey D, Berg R . Geriatric oral health issues in the United States. Int Dent J 2001; 51 (3 Suppl): 254–264.

Douglass CW, Shih A, Ostry L . Will there be a need for complete dentures in the United States in 2020? J Pros Dent 2002; 87: 5–8.

Drake CW, Beck JD . Models for coronal caries and root fragments in an elderly population. Caries Res 1992; 26: 402–407.

Gershen JA . Geriatric dentistry and prevention: research and public policy. Adv Dent Res 1991; 5: 69–73.

Meyerowitz C . Geriatric dentistry and prevention: research and public policy (reaction paper). Adv Dent Res 1991; 5: 74–77.

Locker D . Response and non-response bias in oral health surveys. J Public Health Dent 2000; 60: 72–81.

Drake CW, Beck JD, Lawrence HP, Koch GG . Three-year coronal caries incidence and risk factors in North Carolina elderly. Caries Res 1997; 31: 1–7.

Hawkins RJ, Jutai DKG, Brothwell DJ, Locker D . Three-year coronal caries incidence in older Canadian adults. Caries Res 1997; 31: 405–410.

Lawrence HP, Hunt RJ, Beck JD, Davies GM . Five-year incidence rates and intraoral distribution of root caries among community-dwelling older adults. Caries Res 1996; 30: 169–179.

Lawrence HP, Hunt RJ, Beck JD . Three-year root caries incidence and risk modelling in older adults in North Carolina. J Public Health Dent 1995; 55: 69–78.

Locker D . Incidence of root caries in an older Canadian population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1996; 24: 403–407.

Hand JS, Hunt RJ, Beck JD . Coronal and root caries in older Iowans: 36-month incidence. Gerodontics 1988; 4: 136–139.

Thomson WM, Spencer AJ, Slade GD, Chalmers JM . Is medication a risk factor for dental caries among older people? Evidence from a longitudinal study in South Australia. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2002; 30: 224–232.

Beck JD, Hand JS, Hunt RJ, Field HM . Prevalence of root and coronal caries in a noninstitutionalized older population. J Am Dent Assoc 1985; 111: 964–967.

Graves RC, Beck JD, Disney JA, Drake CW . Root caries prevalence in black and white North Carolina adults over age 65. J Public Health Dent 1992; 52: 94–101.

Locker D, Leake JL . Coronal and root decay experience in older adults in Ontario, Canada. J Public Health Dent 1993; 53: 158–164.

Slade GD, Spencer AJ . Distribution of coronal and root caries experience among persons aged 60+ in South Australia. Aust Dent J 1997; 42: 178–184.

Drake CW, Hunt RJ, Koch GG . Three-year tooth loss among black and white older adults in North Carolina. J Dent Res 1995; 74: 675–680.

Steele JG, Walls AWG, Murray JJ . Partial dentures as an independent indicator of root caries risk in a group of older adults. Gerodontol 1997; 14: 67–74.

Burt BA . Prevention policies in the light of the changed distribution of dental caries. Acta Odont Scand 1998; 56: 179–186.

Galan D, Lynch E . Epidemiology of root caries. Gerodontology 1993; 10: 59–71.

Mattiasson-Robertson A, Twetman S . Prediction of caries incidence in schoolchildren living in a high and a low fluoride area. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1993; 21: 365–369.

Hausen H, Karkkainen S, Seppa L . Application of the high-risk strategy to control dental caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2000; 28: 26–34.

Kruger E, Thomson WM, Poulton R, Davies S, Brown RH, Silva PA . Dental caries and changes in dental anxiety in late adolescence. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1998; 26: 355–359.

Chen M, Andersen RM, Barmes DE, Leclercq M-H, Lyttle CS . Comparing oral health care systems. A second international collaborative study. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1997.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thomson, W. Dental caries experience in older people over time: what can the large cohort studies tell us?. Br Dent J 196, 89–92 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4810900

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4810900

This article is cited by

-

Correlation between microbial host factors and caries among older adults

BMC Oral Health (2021)

-

How effective and cost-effective is water fluoridation for adults? Protocol for a 10-year retrospective cohort study

BDJ Open (2021)

-

A survey of cariology teaching in Australia and New Zealand

BMC Medical Education (2018)

-

Oral hygiene and oral health in older people with dementia: a comprehensive review with focus on oral soft tissues

Clinical Oral Investigations (2018)

-

NHS dental service utilisation and social deprivation in older adults in North West England

British Dental Journal (2017)