Abstract

Optomechanical crystal (OMC) cavities which exploit the simultaneous photonic and phononic bandgaps in periodic nanostructures have been utilized to colocalize, couple, and transduce optical and mechanical resonances for nonlinear interactions and precision measurements. The development of near-infrared OMC cavities has difficulty in maintaining a high optomechanical coupling rate when scaling to smaller mechanical modal mass because of the reduction of the spatial overlap between the optical and mechanical modes. Here, we explore OMC nanobeam cavities in gallium nitride operating at the ultraviolet wavelengths to overcome this problem. With a novel optimization strategy, we have successfully designed an OMC cavity, with a size of 3.83 × 0.17 × 0.13 μm3 and the mechanical modal mass of 22.83 fg, which possesses an optical mode resonating at the wavelength of 393.03 nm and the fundamental mechanical mode vibrating at 14.97 GHz. The radiation-limited optical Q factor, mechanical Q factor, and optomechanical coupling rate are 2.26 × 107, 1.30 × 104, and 1.26 MHz, respectively. Our design and optimization approach can also serve as the general guidelines for future development of OMC cavities with improved device performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Optomechanical crystal (OMC) cavities that support high colocalization of optical and mechanical modes have opened a new era for coherent manipulation of photon–phonon interaction at the nanoscale1,2,3,4,5,6. OMC cavities based on a photonic crystal nanobeam structure7 support ultrahigh optical and mechanical Q factors, femtogram modal masses, gigahertz mechanical vibrations, and high optomechanical coupling rates8. They are highly desirable in the applications of resolved-sideband laser cooling9, optomechanically induced transparency10, high-speed acousto-optic devices11, and ultrasensitive signal detection12,13,14. Silicon has been the predominant platform for the implementation of OMC cavities5,6,7,8,15,16,17. In addition, wide-bandgap semiconductors can offer much more functionalities due to their broadband optical transparency, negligible nonlinear absorption, large Young’s moduli, and large piezoelectric effects. These materials (bandgap, Young’s modulus, refractive index) include aluminum nitride (AlN) (6.00 eV, 308 GPa, 2.20), diamond (5.50 eV, 1035 GPa, 2.40), silicon nitride (Si3N4) (5.00 eV, 310 GPa, 2.07), and gallium nitride (GaN) (3.40 eV, 330 GPa, 2.55). Among them diamond with the largest Young’s modulus is considered as a promising material for OMC cavities18, but its fabrication relies on an angled-etching technique which leads to asymmetric structural cross-sections and relatively low mechanical Q factors19,20. AlN, Si3N4, and GaN all have similar Young’s moduli, and OMC nanobeam cavities based on AlN21,22,23,24 and Si3N425,26 have also been realized. In all the above implementations, it is difficult to obtain both a high optomechanical coupling rate and a small modal mass. Actually, the modal mass of all demonstrated OMC cavities with the optomechanical coupling rate greater than 1.00 MHz has been limited to above 85.00 fg8,15,16,17,18,21,22,23,24,25,26. This limitation is attributed to the reduction of the spatial overlap between the optical and mechanical modes. Since the volume of the optical mode is much larger than that of the mechanical mode, the system suffers from decreasing optomechanical interaction as the mechanical modal mass is reduced further.

In order to overcome the above limitation, we propose GaN-based OMC cavities operating in the ultraviolet regime. With the optical modal volume better matching the mechanical modal volume, such ultraviolet OMC cavities are capable of achieving an ultrasmall modal mass with a high optomechanical coupling rate. Compared with other wide-bandgap semiconductors, the prominent advantage of GaN is its bandedge emission covering the ultraviolet regime27 for integrating optomechanics and optoelectronics28 in a single device. Its mature epitaxial growth, composition, and doping technologies29 have led to high-power laser diodes30 and high-responsivity photodetectors31,32 based on InGaN/GaN multi-quantum-well structures. It has been employed for the realization of passive photonic integrated circuits33, ring resonators34, and two-dimensional photonic crystal cavities35,36. GaN could also be a promising platform for the development of active optomechanics37 in the ultraviolet regime, for studying the strong coupling between ultraviolet photons, GHz phonons, and electrons in the applications of high-speed, strong modulation of semiconductor lasers37 and enhanced mechanical ground-state cooling by optomechanical interaction38. In this paper, we design and numerically investigate GaN-based OMC nanobeam cavities, resonating at an ultrashort optical wavelength8,18,26,39 and vibrating at a high mechanical frequency18,21,22. We optimize the structure based on tuning the OMC mirrors for achieving ultrahigh optical and mechanical Q factors, with the optomechanical coupling rate greater than 1.00 MHz. In contrast to the previous implicit optimization methods8,16,18, our approach provides a step-by-step guideline and is advantageous to fine tuning of the overall device performance, which also applies to other wide-bandgap semiconductor platforms with similar refractive indices.

Results

Structural description and optimization procedure

As shown in Fig. 1, an OMC nanobeam cavity supports both optical and mechanical modes in its center region because it provides an effective potential for the modes. Figure 1(a) shows an overview of the GaN-based OMC cavity. The top GaN nanobeam and the selectively etched sapphire substrate are marked in light blue and white, respectively. The elliptic air holes are introduced to engineer the potential for the optical and mechanical modes. These holes are arranged symmetrically along the nanobeam with respect to its center. Therefore, the OMC cavity can be modeled as a Fabry–Pérot cavity40, whose mirrors provide high reflection for light and sound simultaneously. Consequently, we may refer to one side of the hole array as an “OMC mirror”, whose reflection loss directly determines the intrinsic optical and mechanical Q factors. As shown in Fig. 1(b), an OMC cavity consists of two identical OMC mirrors, each of which consists of a taper and a reflector, with an adjustable cavity length at the center.

Schematic of an ultraviolet OMC nanobeam cavity in GaN.

(a) Angled overview. The inset is a unit cell with dimension labels. (b) Top view. The OMC nanobeam cavity is constructed by joining two OMC mirrors with an adjustable cavity length s, while each OMC mirror consists of both a taper (i = 1–10) and a reflector (i = 11–20) region.

We aim at designing an OMC nanobeam cavity with the optical resonant wavelength around 400.00 nm, the mechanical modal mass around 20.00 fg, and the optomechanical coupling rate greater than 1.00 MHz. In principle, this is achievable through device downscaling and optimization in the entire parameter space, but we find it quite resource-demanding and time-consuming to find an OMC cavity with decent Q factors and optomechanical coupling rate simultaneously. Therefore, we have developed a new optimization procedure listed in the following four steps:

-

1

Designing the OMC mirror for obtaining high optical reflection in the targeted wavelength range and photonic and phononic bandgaps for the defect modes.

-

2

Obtaining high-Q optical and mechanical modes by varying the cavity length, during which the mismatch between the wavelengths of the optical mode and the OMC mirror’s reflection peak can be calibrated. By Steps 1 and 2 we should achieve an optical Q factor over 20 million and an optomechanical coupling rate around 0.80 MHz, which are important for the next fine-tuning steps.

-

3

Enhancing the optomechanical coupling rate to be greater than 1.00 MHz by decreasing all the lattice constants with the same factor, which improves the spatial overlap between the optical and mechanical modes.

-

4

Maximizing the optical Q factor by fine tuning the cavity length while maintaining the optomechanical coupling rate above 1.00 MHz. This step corrects the slight mismatch between the wavelengths of the optical mode and the OMC mirror’s refection peak introduced during Step 3 and obtains an overall optimized result of both the optical Q factor and the optomechanical coupling rate.

Designing the OMC mirrors

The following parameters of GaN are used for designing the OMC naonbeam cavity. The wavelength (λ) dependence of the refractive index follows41

The density, Young’s modulus, and Poisson’s ratio are 6150 kg m−3, 330 GPa, and 0.183, respectively42,43. The thermal expansion coefficient, thermal conductivity, and heat capacity at room temperature (300 K) are 3.17 × 10−6 K−1, 220 W m−1 K−1, and 429.50 J kg−1 K−1, respectively44,45,46.

We first design the OMC mirrors in order to obtain near-unity reflection for obtaining ultrahigh optical Q factors. We use elliptic air holes to construct the OMC mirrors for achieving high mechanical modal frequency. In the design illustrated in Fig. 1(b), we fix the total number of air holes to be 10 in both the taper and reflector regions, and use a quadratic taper for adiabatic mode transition with reduced scattering loss. The i-th (i = 1–20) unit cell has a lattice constant ai, with the x- and y-diameter of the elliptic air hole hxi and hyi, respectively. The beam width w and thickness t are set to be 170 nm and 130 nm, respectively. The center-to-center separation between the two innermost air holes is denoted to be s, which can be used to tune the cavity length. In the taper region hxi, hyi, and ai are quadratically varied from the 1st to the 10th unit cell. We preset both hy1 and hx10 to be 50 nm, an achievable feature size with typical electron-beam lithography and dry etching processes. We also set the lattice constant a10 to be 115 nm for obtaining a quasiphotonic bandgap at a wavelength around 400.00 nm. For i < 10, ai is varied according to 115 × [1 − C × (9.5 − i)2] where C is 0.001565, the quadratic coefficient for achieving adiabatic mode transition. The parameters in the reflector region from the 10th to the 20th unit cell remain the same. Therefore, we will focus on hx1, hy10, and s for subsequent design and optimization.

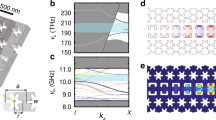

The photonic and phononic band diagrams of both the 1st and the 10th unit cell as shown in Fig. 2(a) and (b) are calculated using MPB47 and COMSOL Multiphysics48, respectively, to determine hx1 and hy10. The refractive index of GaN is set to be 2.55 in spite of a slight dispersion (n = 2.44–2.60) between 600.00 and 780.00 THz. In Fig. 2(a), only the dielectric bands are plotted because the air-band modes with photon energy higher than GaN’s electronic bandgap are highly lossy. The light cone is above and out of the zoomed band diagram region. The points with kx = 0.50·(2π/ai), which are labelled as Xoi with i the numerical order of a unit cell, are used for determining the quasiphotonic bandgap and the localized photonic mode. The optical modal frequency (fo) at Xo1 for the 1st unit cell is inside the quasiphotonic bandgap of the 10th unit cell, as indicated by the pink region. In Fig. 2(b), the phononic bands with y- and z-symmetry of the 1st and the 10th unit cell are provided. Here the points with both kx = 0 and 0.50·(2π/ai), which are labelled as Γmi and Xmi respectively, are used for determining the quasiphononic bandgap and the localized mechanical mode. With hxi decreasing and hyi increasing, the mechanical modal frequencies (fm) at Γm1 and Xm1 shift respectively to the higher and lower side, thereby creating a large quasiphononic bandgap as indicated by the pink region. Figure 2(c) and (d) plot the respective optical and mechanical frequencies at Xoi, Γmi, and Xmi for the 1st and 10th unit cell as hx1 or hy10 varies. Since fo of the air band at kx = 0.50·(2π/ai) of the 10th unit cell is always larger than 799.92 THz with the varying hy10, fo at Xo1 of the 1st unit cell remains safely inside the quasiphotonic bandgap of the 10th unit cell. Additionally, Fig. 2(c) shows opposite trends for fo and fm with the varying hx1 of the 1st unit cell. In order to obtain both high optical and mechanical frequencies, we may choose hx1 to be 60 nm, with the corresponding fo at Xo1 762.20 THz and fm at Γm1 15.43 GHz. Lastly, in order to obtain both large quasiphotonic and quasiphononic bandgaps, we may choose hy10 to be 110 nm, with the corresponding fm at Γm10 and Xm10 17.44 GHz and 9.12 GHz, respectively. Therefore, the structural parameters (hxi, hyi, ai) for the 1st and the 10th unit cell have been determined to be (60, 50, 102) nm and (50, 110, 115) nm, respectively.

Designing high-performance OMC mirrors.

(a) Photonic band diagrams of the 1st and the 10th unit cells. The pink-shaded region denotes the photonic bandgap of the 10th unit cell. Insets are the Ey-field profiles at Xo1 and Xo10 for the 1st and the 10th unit cell, respectively. (b) Phononic band diagrams with y- and z-symmetry of the 1st and the 10th unit cells. The pink-shaded region denotes the phononic bandgap of the 10th unit cell. Insets are the displacement fields of the two mechanical modes at Γm1 and Xm1 for the 1st unit cell. (c,d) Optical modal frequency fo at Xo1 (Xo10) and mechanical modal frequency fm at Γm1 (Γm10) and Xm1 (Xm10) versus hx1 (hy10) for the 1st (10th) unit cell. (e) Assignment of hxi, hyi, and ai (i = 1–10) for the unit cells in the taper region. (f) Spectra of reflection and the corresponding loss of the OMC mirror.

The structural parameters of the rest eight elliptic air holes in the taper region are determined by following a quadratic relation similar to that of ai. Here, the quadratic variation refers to the dependence of the structural parameters on the unit cell number i, which in principle allows for two types of parabolas—opening upward and downward. We have chosen the downward-opening type with the specific parameters shown in Fig. 2(e) for obtaining better performance, such as small optical modal volume, small mechanical modal mass, and high optomechanical coupling rate. With the structural design of the OMC mirror completed, we calculated its reflection and reflection-loss spectra as shown in Fig. 2(f). The reflection coefficient reaches the peak value of 99.99% at the wavelength of 405.53 nm, where the corresponding reflection loss is at least 30.7 times lower than that at 404.50 nm and 406.50 nm.

Obtaining the high-Q optical and mechanical modes

We construct an initial design of OMC cavity by joining two identical OMC mirrors facing each other as shown in Fig. 1(b). We obtained the radiation-limited optical Q factor (Qo) by using MEEP49, where the material dispersion of GaN is incorporated. We also calculated the optical modal volume with the definition Vo = ∫ ε|E|2 dV/max(ε|E|2). The simulated optical mode has a resonant wavelength of 405.66 nm with Qo of 5.14 × 106. The resonant wavelength is 0.13 nm away from that of the OMC mirror’s reflection peak, indicating room for further optimization of Qo. The round-trip loss can be reduced by a factor of 3.66 if the reflection loss is suppressed from 1.30 × 10−4 to the minimum 6.80 × 10−5.

The mechanical loss consists of two contributions: one is clamping (CL) loss due to leakage of the acoustic waves into the substrate, and the other is thermoelastic damping (TED) loss due to energy conversion and dissipation from the strain field into the temperature field17. Consequently, the total mechanical Q factor can be expressed as 1/Qm = 1/ + 1/

+ 1/ .

.  is usually proportional to the total number of air holes in the reflector. In our design 10 air holes are sufficient for obtaining negligible acoustic wave leakage.

is usually proportional to the total number of air holes in the reflector. In our design 10 air holes are sufficient for obtaining negligible acoustic wave leakage.

The optomechanical coupling rate is defined as the cavity’s optical frequency shift induced by a mechanical zero-point displacement5. It can be calculated based on a perturbation theory1, by including contributions from the moving boundary (MB) and the photoelastic (PE) effects. The total optomechanical coupling rate is expressed as g0 = (gMB + gPE)·(ħ/4πmefffm)1/2, where fm and meff are respectively the resonant frequency and modal mass of the mechanical mode. The moving boundary contribution gMB is expressed as

where ωo is the optical resonant frequency, Q is the normalized displacement field, and  is the surface normal vector. ε is the material’s permittivity so that

is the surface normal vector. ε is the material’s permittivity so that  and

and  . E|| and D⊥ are respectively the parallel component of the electric field and the perpendicular component of the electric displacement field with respect to the integral surface. The photoelastic contribution gPE is expressed as

. E|| and D⊥ are respectively the parallel component of the electric field and the perpendicular component of the electric displacement field with respect to the integral surface. The photoelastic contribution gPE is expressed as

where ε0 is the vacuum’s permittivity, n(λo) is the refractive index of GaN at the optical resonant wavelength, Sij (i, j = x, y, z) is the strain field, and pmn (m, n = 1–6) is the photoelastic coefficient of GaN in wurtzite structure50.

For an as-constructed OMC cavity with the cavity length (center-to-center separation s) of 102.00 nm, we obtained Qo,  , Qm, and g0/2π respectively to be 5.14 × 106, 1.59 × 107, 1.35 × 104, and 873.95 kHz. We have an extra degree of freedom for optimization, i.e., tuning s around its initial value to get the maximal Qo. Figure 3(a–c) shows the results of the optical and mechanical Q factors, optomechanical coupling rates, and optical modal volume and mechanical modal mass as s varies from 99.00 to 104.00 nm. Qo reaches the maximum when s is 101.70 nm, where the values of Qo,

, Qm, and g0/2π respectively to be 5.14 × 106, 1.59 × 107, 1.35 × 104, and 873.95 kHz. We have an extra degree of freedom for optimization, i.e., tuning s around its initial value to get the maximal Qo. Figure 3(a–c) shows the results of the optical and mechanical Q factors, optomechanical coupling rates, and optical modal volume and mechanical modal mass as s varies from 99.00 to 104.00 nm. Qo reaches the maximum when s is 101.70 nm, where the values of Qo,  , Qm, and g0/2π are 2.19 × 107, 1.33 × 107, 1.35 × 104, and 890.88 kHz, respectively. These numbers meet the milestone prescribed in our design procedure and represent a good starting point for further optimization steps.

, Qm, and g0/2π are 2.19 × 107, 1.33 × 107, 1.35 × 104, and 890.88 kHz, respectively. These numbers meet the milestone prescribed in our design procedure and represent a good starting point for further optimization steps.

Designing high-Q optical and mechanical modes.

(a–c) Effects of tuning the center-to-center separation s on the optical and mechanical Q factors (a), optomechanical coupling rates (b), and optical modal volume and mechanical modal mass (c). (d) Normalized Ey-field, mechanical displacement field, and temperature profile at 300 K for the optimized OMC cavity with s = 101.70 nm.

The optical resonant wavelength is 405.51 nm, which is now only 0.02 nm away from that of the OMC mirror’s reflection peak. The optical modal volume Vo is 2.34 × 10−3 μm3 or 0.58·(λres/n)3. The mechanical modal mass is 22.79 fg. The mechanical resonant frequency is 15.22 GHz and is well below the upper limit (16.54 GHz) of the quasiphononic bandgap, which results in extremely small clamping loss. Nonetheless, the total mechanical Q factor is largely limited by the TED loss under ambient temperature, yielding a Qm three orders of magnitude lower than  and the corresponding fm·Qm product of 2.05 × 1014 Hz at 300 K. Figure 3(d) plots the normalized electric field, mechanical displacement field, and temperature profile of the optimized OMC cavity with s of 101.70 nm. It is easy to find that the optical mode and mechanical mode are colocalized in the center region with substantial spatial overlap.

and the corresponding fm·Qm product of 2.05 × 1014 Hz at 300 K. Figure 3(d) plots the normalized electric field, mechanical displacement field, and temperature profile of the optimized OMC cavity with s of 101.70 nm. It is easy to find that the optical mode and mechanical mode are colocalized in the center region with substantial spatial overlap.

Enhancing the optomechanical coupling rate

In the last step, we obtained high Q factors, but the optomechanical coupling rate was below 1.00 MHz. A close examination of Fig. 3(b) reveals a monotonic relation between g0 and s: gPE as the dominating term of g0 increases from 1108.14 to 1396.02 kHz when s reduces from 104.00 to 99.00 nm. This can be attributed to the increased overlap integral between the optical mode’s electric field Ei and the mechanical mode’s strain field Sij as defined in Eq. (3).

In this optimization step, we enhance the optomechanical coupling rate by compressing all the lattice constants ai by a scaling factor to increase the overlap between the electric field Ei and strain field Sij (ref. 17). The effects of such an ai-downscaling process are straightforward in Fig. 4(a) and (b): when the scaling factor varies from 1.00 to 0.90, the optical modal volume reduces to 1.56 × 10−3 μm3 or 0.50·(λres/n)3, while the mechanical modal mass (volume) keeps increasing. The opposite dependence produces enhanced overlap between the optical and mechanical modes, yielding increased g0 as shown in Fig. 4(c). In the meantime, compression of all the lattice constants leads to larger values of hxi/ai, and consequently a shorter optical resonant wavelength as shown in Fig. 4(a). For example, the resonant wavelength shifts to 380.22 nm when the scaling factor is 0.90. Therefore, this downscaling process may induce a slight mismatch between the wavelengths of the optical mode and the OMC mirror’s refection peak although both are blue shifted. Figure 4(c) shows the results of the enhanced optomechanical coupling rates. For example, the total optomechanical coupling rate g0/2π reaches 1.26 MHz and 1.66 MHz when the scaling factor is 0.95 and 0.90, respectively. Therefore, one can choose a proper scaling factor for a desired g0/2π.

In order to better understand how the ai-downscaling process leads to the enhancement of g0, we list in Table 1 the individual contributions where gPEi (i = 1–4) refers to the result calculated from the i-th term of the integrand in the right-hand side of Eq. (3). It is obvious that gPE3 which corresponds to the overlap between |Ey|2 and (Sxx, Syy, Szz) has the largest increment and is thus dominating. As a reference, we plot in Fig. 5 the spatial distributions of the electric field of the optical mode, and the strain and displacement field of the mechanical mode. Apparently, Ex and Ez are considerably weaker than Ey, leading to very small overlap integrals for gPE1, gPE2, and gPE4. On the other hand, by comparing the profiles of |E|2 and |S|, one may identify that the optical modal volume is still slightly larger than the mechanical modal volume, indicating that the optomechanical coupling rate has further room for enhancement.

Optimizing the Q factors while maintaining the high optomechanical coupling rate

The last step of ai-downscaling induces different amounts of blue shift of the wavelengths of the optical mode and the OMC mirror’s refection peak and thus a slight mismatch between them, resulting in degradation of Qo. For example, when the scaling factor is 0.95 with the correspondingly updated s of 96.62 nm (0.95 × 101.70 nm), the resonant wavelength blueshifts to 393.13 nm and Qo drops from the previously optimized 2.19 × 107 to 1.09 × 107. Meanwhile, the reflection peak of the compressed OMC mirror blueshifts to 392.98 nm. Similar to the implementation in Step 2, we may retrieve the high Qo by fine tuning the cavity length. The purpose of this fine-tuning step is to enhance Qo substantially at little expense of g0 reduction. Figure 6 shows the variation of all the previous simulated properties with the cavity length s tuned around 96.62 nm. When s is readjusted to 96.44 nm (0.95 × 101.52 nm), Qo reaches the maximum again, with Qo,  , Qm, and g0/2π being respectively 2.26 × 107, 1.18 × 107, 1.30 × 104, and 1259.12 kHz. The corresponding optical resonant wavelength, optical modal volume, mechanical resonant frequency, and mechanical modal mass are respectively 393.03 nm, 0.54·(λres/n)3, 14.97 GHz, and 22.83 fg. A comparison of these parameters with those in Step 2 concludes that the optical modal volume is reduced from 0.58·(λres/n)3 to 0.54·(λres/n)3 while the mechanical modal mass is increased from 22.79 to 22.83 fg, which contributes to a better modal overlap and a high optomechanical coupling rate above 1.00 MHz.

, Qm, and g0/2π being respectively 2.26 × 107, 1.18 × 107, 1.30 × 104, and 1259.12 kHz. The corresponding optical resonant wavelength, optical modal volume, mechanical resonant frequency, and mechanical modal mass are respectively 393.03 nm, 0.54·(λres/n)3, 14.97 GHz, and 22.83 fg. A comparison of these parameters with those in Step 2 concludes that the optical modal volume is reduced from 0.58·(λres/n)3 to 0.54·(λres/n)3 while the mechanical modal mass is increased from 22.79 to 22.83 fg, which contributes to a better modal overlap and a high optomechanical coupling rate above 1.00 MHz.

Maximizing the optical Q factor while maintaining a high optomechanical coupling rate.

Effects of fine tuning the center-to-center separation s on the optical and mechanical Q factors (a), optomechanical coupling rates (b), optical resonant wavelength and modal volume (c), and mechanical resonant frequency and modal mass (d).

It should be noted that g0/2π maintains greater than 1.00 MHz in the entire s tuning range in Fig. 6(b), indicating the existence of a sufficiently wide window for fine tuning the optical resonance. We also simulated OMC cavities of even smaller scaling factors. When the scaling factor is 0.92, the optimized OMC cavity resonating at optical wavelength 385.19 nm, mechanical frequency 14.79 GHz possesses Qo, Qm, meff, and g0/2π of 1.29 × 107, 1.28 × 104, 23.36 fg, and 1539.97 kHz, respectively. When the scaling factor is 0.90, the optimized Qo can still reach a high value 1.02 × 107, with the corresponding resonant wavelength as short as 380.16 nm and g0/2π as high as 1805.88 kHz.

Discussion

Table 2 compares the simulated performance of our GaN-based OMC nanobeam cavities with those of the state-of-the-art designs8,18. The design in this work has a shorter optical resonant wavelength 393.03 nm, a higher mechanical frequency 14.97 GHz, and a smaller modal mass 22.83 fg. The modal mass is comparable with the designed values of the world’s smallest optomechanical systems based on the concept of NEMS-in-cavity51,52. The large optomechanical coupling rate 1.26 MHz facilitates obtaining a large cooperativity for strong photon–phonon interaction5. In addition, the design and optimization approach we have developed is intuitive and straightforward, by avoiding searching from a large parameter space of numerous realizations.

A good figure of merit for evaluating different OMC cavities is the fm·Qm product5,53,54,55,56 due to the trade-off between fm and Qm57. Since Qm is temperature dependent, it is important to compare all of them at the same temperature, i.e., 300 K. Therefore, we estimated the Qm at 300 K based on their values in refs 8,9,16 and the relation  , where E, α, T0, and Cp are the Young’s modulus, the thermal expansion coefficient, the equilibrium temperature, and the heat capacity, respectively58. From the comparison in Fig. 7, one may notice that this work with a fm·Qm product of 1.95 × 1014 Hz represents a high value along with three other works (refs 8,16,17) in the 1014 Hz regime. It should also be noted that the mechanical frequencies of previous OMC nanobeam cavities are all below ~10 GHz (ref. 18 not included due to the unavailability of Qm), because of the relatively large device size for supporting the near-infrared optical resonances (λres ≥ 980 nm). It is clear that an ultraviolet OMC nanobeam cavity investigated in this work provides a way for obtaining superhigh mechanical frequency, ultrasmall modal mass, and strong optomechanical coupling in a single device.

, where E, α, T0, and Cp are the Young’s modulus, the thermal expansion coefficient, the equilibrium temperature, and the heat capacity, respectively58. From the comparison in Fig. 7, one may notice that this work with a fm·Qm product of 1.95 × 1014 Hz represents a high value along with three other works (refs 8,16,17) in the 1014 Hz regime. It should also be noted that the mechanical frequencies of previous OMC nanobeam cavities are all below ~10 GHz (ref. 18 not included due to the unavailability of Qm), because of the relatively large device size for supporting the near-infrared optical resonances (λres ≥ 980 nm). It is clear that an ultraviolet OMC nanobeam cavity investigated in this work provides a way for obtaining superhigh mechanical frequency, ultrasmall modal mass, and strong optomechanical coupling in a single device.

Plot of fm·Qm product (300 K) with mechanical frequency of OMC nanobeam cavities in various materials.

The fm·Qm value of 1.95 × 1014 Hz from this work is in the 1014 Hz region (yellow shaded) along with three other works (refs 8,16,17). References with a star in the superscript represent experimental results.

To fabricate such a GaN OMC nanobeam cavity, one may adopt the fabrication method in ref. 59. The designed pattern is first transferred to a SiO2 hardmask with high-resolution electron-beam lithography with a resist ZEP520A. The SiO2 hardmask is then used during the etching of GaN using chlorine-based inductively coupled plasma. Finally the SiO2 hardmask is removed by a hydrofluoric acid solution and the GaN nanobeam is released from the substrate by selective etching. Next we study the tolerance to fabrication imperfections of our proposed GaN nanobeam cavities. The statistical evaluation on fabrication disorder60,61 has concluded that the standard deviation of the air holes’ positions and radii in the fabricated photonic crystal nanocavities is less than 0.58 nm. Therefore, we impose random variations satisfying a normal distribution with a standard deviation σ on both radii and center positions of all the air holes of the optimized cavity. Figure 8 lists the simulated optical Q factor, mechanical Q factor, optomechanical coupling rate, fm·Qm product, and effective mass for 20 samples with σ = 0.5 nm and 1.0 nm, respectively. The average values of the simulated Qo, Qm, g0/2π, fm·Qm, and meff are 1.64 × 105, 1.24 × 104, 1.24 MHz, 1.85 × 1014 Hz, and 21.38 fg when σ is 0.5 nm, and are 4.57 × 104, 1.22 × 104, 1.13 MHz, 1.82 × 1014 Hz, and 20.57 fg when σ is 1.0 nm. A comparison with those of the optimized cavity concludes that Qm, g0/2π, and fm·Qm decrease slightly while Qo is more sensitive to fabrication errors due to the increased reflection loss from the OMC mirrors. A recent paper62 reports an experimentally demonstrated Qo of 55,000 at the wavelength of 788.35 nm in GaN ring resonators with the absorption coefficient (α) of ~60 cm−1 (ref. 63). The absorption coefficient becomes ~220 cm−1 at our designed wavelength of 393.03 nm (ref. 63). According to the relation  (ref. 59), the Qabs at 393.03 nm is expected to decrease by 1.82 times from that at 788.35 nm. Due to GaN being an optically active material, its spontaneous emission spectrum can cover the wavelength range of 355–410 nm (ref. 27). The broadband tunable optical gain can also be obtained by incorporating InxGa1−xN fragmented quantum wells64. Therefore, the slight material-limited absorption loss could be eliminated by optically pumping the material to its transparency level65.

(ref. 59), the Qabs at 393.03 nm is expected to decrease by 1.82 times from that at 788.35 nm. Due to GaN being an optically active material, its spontaneous emission spectrum can cover the wavelength range of 355–410 nm (ref. 27). The broadband tunable optical gain can also be obtained by incorporating InxGa1−xN fragmented quantum wells64. Therefore, the slight material-limited absorption loss could be eliminated by optically pumping the material to its transparency level65.

Simulated performance of 20 samples of GaN nanobeam cavity with fabrication imperfections.

(a–c) Effects of randomly varied radii and positions of all air holes (σ = 0.5 nm) on the optical and mechanical Q factors (a), optomechanical coupling rate (b), fm·Qm product and mechanical modal mass (c). (d–f) Effects of randomly varied radii and positions of all air holes (σ = 1.0 nm) on the optical and mechanical Q factors (d), optomechanical coupling rate (e), fm·Qm product and mechanical modal mass (f).

In conclusion, we investigated for the first time ultraviolet OMC cavities based on GaN, for obtaining high optomechanical coupling rate during device miniaturization. With a novel design and optimization strategy based on tuning the OMC mirrors, we can improve the modal confinement as well as the spatial overlap between the optical and mechanical modes, which enables the simultaneous achievement of high Q factors, high mechanical frequency, ultrasmall modal mass, and high optomechanical coupling rate. For the optimized OMC nanobeam cavity, the modal mass 22.83 fg is comparable with the designed values of the world’s smallest optomechanical systems51,52, yet a high optomechanical coupling rate greater than 1.00 MHz is also achieved. The fm·Qm product is in the 1014 Hz regime. Our design and optimization procedure specifies the motivation and objectives clearly in each step, and avoids the blind comprehensive search in the entire space of structural parameters. Therefore, our approach can serve as the general guidelines for developing high-performance OMC nanobeam cavities at other wavelengths or in other materials.

Methods

The photonic band diagrams are computed using MPB, where a supercell with a size of ai × 1.00 × 1.00 μm3 is encapsulated with periodic boundary conditions. The phononic band diagrams are computed using the structural mechanics module in COMSOL, with the two faces normal to the x direction imposed with the Floquet periodic boundary conditions and all the other faces free to move. The reflection spectrum of the OMC mirror is calculated with Lumerical FDTD Solutions66 by incorporating the material dispersion of GaN. The radiation-limited optical Q factors are computed using MEEP. The computation domain has a total size of 6.00 × 1.40 × 1.20 μm3, which includes the entire nanobeam cavity with the surrounding air and perfectly matched layers with a thickness of 0.40 μm. The clamping-loss-limited mechanical Q factors are obtained in COMSOL by computing the ratio of the real part and twice of the imaginary part of the complex modal frequency of the mechanical mode following a method described in ref. 67. The following photoelastic constants are employed during calculation of the optomechanical coupling rates50: p11 = p22 = 0.031, p33 = 0.033, p12 = p21 = 0.008, p13 = p31 = 0.006, p23 = p32 = 0.006, p44 = 0.010, p55 = p66 = 0.012. The OMC cavity is simulated in COMSOL simultaneously with the electromagnetic waves and structural mechanics modules under the same mesh to obtain the surface and volume integrals in Eqs (2) and (3).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Zhou, W. et al. Ultraviolet optomechanical crystal cavities with ultrasmall modal mass and high optomechanical coupling rate. Sci. Rep. 6, 37134; doi: 10.1038/srep37134 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Eichenfield, M., Chan, J., Camacho, R. M., Vahala, K. J. & Painter, O. Optomechanical crystals. Nature 462, 78–82 (2009).

Hill, J. T., Safavi-Naeini, A. H., Chan, J. & Painter, O. Coherent optical wavelength conversion via cavity optomechanics. Nat. Commun. 3, 1196 (2012).

Bochmann, J., Vainsencher, A., Awschalom, D. D. & Cleland, A. N. Nanomechanical coupling between microwave and optical photons. Nat. Phys. 9, 712–716 (2013).

Balram, K. C., Davanço1, M. I., Song, J. D. & Srinivasan, K. Coherent coupling between radiofrequency, optical and acoustic waves in piezo-optomechanical circuits. Nat. Photonics. 10, 346–352 (2016).

Aspelmeyer, M., Kippenberg, T. J. & Marquard, F. Cavity optomechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 1391–1452 (2014).

Pfeifer, H., Paraïso1, T., Zang, L. & Painter, O. Design of tunable GHz-frequency optomechanical crystal resonators. Opt. Express 24, 11407–11419 (2016).

Quan, Q. & Loncar, M. Deterministic design of wavelength scale, ultra-high Q photonic crystal nanobeam cavities. Opt. Express 19, 18529–18542 (2011).

Chan, J., Safavi-Naeini, A. H., Hill, J. T., Meenehan, S. & Painter, O. Optimized optomechanical crystal cavity with acoustic radiation shield. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 081115 (2012).

Chan, J. et al. Laser cooling of a nanomechanical oscillator into its quantum ground state. Nature 478, 89–92 (2011).

Safavi-Naeini, A. H. et al. Electromagnetically induced transparency and slow light with optomechanics. Nature 472, 69–73 (2011).

Tadesse, S. A. & Li, M. Sub-optical wavelength acoustic wave modulation of integrated photonic resonators at microwave frequencies. Nat. Commun. 5, 5402 (2014).

Quan, Q. et al. Single particle detection in CMOS compatible photonic crystal nanobeam cavities. Opt. Express 21, 32225–32233 (2013).

Zhang, H. et al. Design of a femtogram scale double-slot photonic crystal optomechanical cavity. Opt. Express 23, 23167–23176 (2015).

Zhang, H. et al. Femtogram scale nanomechanical resonators embedded in a double-slot photonic crystal nanobeam cavity. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 051106 (2016).

Navarro-Urrios, D. et al. Dynamical back-action at 5.5 GHz in a corrugated optomechanical beam. AIP Adv. 4, 124601 (2014).

Huang, Z. L. et al. Strong Optomechanical Coupling in Nanobeam Cavities based on Hetero Optomechanical Crystals. Sci. Rep. 5, 15964 (2015).

Li, Y. Z. et al. Optomechanical crystal nanobeam cavity with high optomechanical coupling rate. J. Opt. 17, 045001 (2015).

Kipfstuhl, L., Guldner, F., Riedrich-Moller, J. & Becher, C. Modeling of optomechanical coupling in a phoxonic crystal cavity in diamond. Opt. Express 22, 12410–12423 (2014).

Tao, Y., Boss, J. M., Moores, B. A. & Degen, C. L. Single-crystal diamond nanomechanical resonators with quality factors exceeding one million. Nat. Commun. 5, 3638 (2014).

Bureka, M. et al. Diamond optomechanical crystals. Available at: http://arxiv.org/abs/1512.04166. (Accessed: 14th December 2015).

Tadesse, S. A., Li, H., Liu, Q. Y. & Li, M. Acousto-optic modulation of a photonic crystal nanocavity with Lamb waves in microwave K band. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 201113 (2015).

Li, H., Tadesse, S. A., Liu, Q. & Li, M. Nanophotonic cavity optomechanics with propagating acoustic waves at frequencies up to 12 GHz. Optica 2, 826–831 (2015).

Fan, L., Sun, X., Xiong, C., Schuck, C. & Tang, H. X. Aluminum nitride piezo-acousto-photonic crystal nanocavity with high quality factors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 153507 (2013).

Xiong, C. et al. Aluminum nitride as a new material for chip-scale optomechanics and nonlinear optics. New J. Phys. 14, 095014 (2012).

Davanco, M., Ates, S., Liu, Y. & Srinivasan, K. Si3N4 optomechanical crystals in the resolved-sideband regime. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 041101 (2014).

Grutter, K. E., Davanco, M. & Srinivasan, K. Si3N4 Nanobeam Optomechanical Crystals. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 21, 2700611 (2015).

Zhang, Q. et al. A room temperature low-threshold ultraviolet plasmonic nanolaser. Nat. Commun. 5, 4953 (2014).

Luan, X. S. et al. An integrated low phase noise radiation-pressure-driven optomechanical oscillator chipset. Sci. Rep. 4, 6842 (2014).

Nakamura, S., Pearton, S. & Fasol, G. The Blue Laser Diode: The Complete Story (Springer, 2000).

Feezell, D. F. et al. AlGaN-cladding-free nonpolar InGaN/GaN laser diodes. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 46, L284–L286 (2007).

Pereiro, J. et al. Optimization of InGaN-GaN MQW Photodetector Structures for High-Responsivity Performance. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 45, 617–622 (2009).

Tchernycheva, M. et al. Integrated Photonic Platform Based on InGaN/GaN Nanowire Emitters and Detectors. Nano Lett. 14, 3515–3520 (2014).

Dharanipathy, U. et al. Near-infrared characterization of gallium nitride photonic-crystal waveguides and cavities. Opt. Lett. 37, 4588–4590 (2012).

Xiong, C. et al. Integrated GaN photonic circuits on silicon (100) for second harmonic generation. Opt. Express 19, 10462–10470 (2011).

Roland, I. et al. Near-infrared gallium nitride two-dimensional photonic crystal platform on silicon. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 011104 (2014).

Zeng, Y. et al. Resonant second harmonic generation in a gallium nitride two-dimensional photonic crystal on silicon. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 081105 (2015).

Yang W. et al. Laser optomechanics. Sci. Rep. 5, 13700 (2015).

Ge, L., Faez, S., Marquardt, F. & Tureci, H. E. Gain-tunable optomechanical cooling in a laser cavity. Phys. Rev. A 87, 053839 (2013).

Balram, K. C., Davanco, M., Lim, J. Y., Song, J. D. & Srinivasan, K. Moving boundary and photoelastic coupling in GaAs optomechanical resonators. Optica 1, 414–420 (2014).

McCutcheon, M. W. & Loncar, M. Design of a silicon nitride photonic crystal nanocavity with a Quality factor of one million for coupling to a diamond nanocrystal. Opt. Express 16, 19136–19145 (2008).

Barker, A. S. & Ilegems, M. Infrared Lattice Vibrations and Free-Electron Dispersion in GaN. Phys. Rev. B 7, 743–750 (1973).

Yang, Z. et al. Mechanical characterization of suspended GaN microstructures fabricated by GaN-on-patterned-silicon technique. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 041913 (2006).

Moram, M. A., Barber, Z. H. & Humphreys, C. J. Accurate experimental determination of the Poisson’s ratio of GaN using high-resolution x-ray diffraction. J. Appl. Phys. 102, 023505 (2007).

Leszczynski, M. et al. Thermal expansion of gallium nitride. J. Appl. Phys. 76, 4909–4911 (1994).

Jezowski, A. et al. Thermal conductivity of GaN crystals in 4.2–300 K range. Solid State Commun. 128, 69–73 (2003).

Leitner, J., Strejc, A., Sedmidubsky, D. & Ruzicka, K. High temperature enthalpy and heat capacity of GaN. Thermochim. Acta 401, 169–173 (2003).

Johnson, S. G. & Joannopoulos, J. D. Block-iterative frequency-domain methods for Maxwell’s equations in a planewave basis. Opt. Express 8, 173–190 (2001).

COMSOL Group, http://www.comsol.com/.

Oskooi, A. F. et al. MEEP: A flexible free-software package for electromagnetic simulations by the FDTD method. Comput. Phys. Commun. 181, 687–702 (2010).

Davydov, S. Y. & Tikhonov, S. K. Photoelasticity and quadratic permittivity of wide-gap semiconductors. Semiconductors 31, 698–699 (1997).

Zheng, J. J. et al. Femtogram dispersive L3-nanobeam optomechanical cavities: design and experimental comparison. Opt. Express 20, 26486–26498 (2012).

Sun, X. K., Zheng, J. J., Poot, M., Wong, C. W. & Tang, H. X. Femtogram Doubly Clamped Nanomechanical Resonators Embedded in a High-Q Two-Dimensional Photonic Crystal Nanocavity. Nano Lett. 12, 2299–2305 (2012).

Lu, X., Lee, J. Y. & Lin, Q. High-frequency and high-quality silicon carbide optomechanical microresonators. Sci. Rep. 5, 17005 (2015).

Norte, R. A., Moura, J. P. & Gröblacher, S. Mechanical resonators for quantum optomechanics experiments at room temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 147202 (2016).

Feng, X. L., He, R., Yang, P. & Roukes, M. L. Very high frequency silicon nanowire electromechanical resonators. Nano Lett. 7, 1953–1959 (2007).

Nguyen, C. MEMS technology for timing and frequency control. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelect. Freq. Control 54, 251–270 (2007).

Chandorkar, S. A. et al. Limits of quality factor in bulk-mode micromechanical resonators. In 21st IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems Tucson, AZ, p. 74 (MEMS 2008).

Lifshitz, R. & Roukes, M. L. Thermoelastic damping in micro- and nanomechanical systems. Phys. Rev. B 61, 5600–5609 (2000).

Triviño, N. V. et al. High quality factor two dimensional GaN photonic crystal cavity membranes grown on silicon substrate. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 071103 (2012).

Hagino, H., Takahashi, Y., Tanaka, Y., Asano, T. & Noda, S. Effects of fluctuation in air hole radii and positions on optical characteristics in photonic crystal heterostructure nanocavities. Phys. Rev. B 79, 085112 (2009).

Taguchi, Y., Takahashi, Y., Sato, Y., Asano, T. & Noda, S. Statistical studies of photonic heterostructure nanocavities with an average Q factor of three million. Opt. Express 19, 11916 (2011).

Bruch, A. W. et al. Broadband nanophotonic waveguides and resonators based on epitaxial GaN thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 141113 (2015).

Yu, G. et al. Optical properties of wurtzite structure GaN on sapphire around fundamental absorption edge (0.78–4.77 eV) by spectroscopic ellipsometry and the optical transmission method. Appl. Phys. Lett. 70, 3209 (1997).

Niu, N. et al. Ultra-low threshold gallium nitride photonic crystal nanobeam laser. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 231104 (2015).

Simeonov, D. et al. High quality nitride based microdisks obtained via selective wet etching of AlInN sacrificial layers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 171102 (2008).

Lumerical Solutions, Inc. http://www.lumerical.com/tcad-products/fdtd/.

Eichenfield, M., Chan, J., Safavi-Naeini, A. H., Vahala, K. J. & Painter, O. Modeling dispersive coupling and losses of localized optical and mechanical modes in optomechanical crystals. Opt. Express 17, 20078–20098 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by a grant from the NSFC/RGC Joint Research Scheme sponsored by the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. N_CUHK415/15), and partially supported by Project No. BME-p5-15 of the Shun Hing Institute of Advanced Engineering and Direct Grant for Research of the Faculty of Engineering, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.S. conceived the project; W.Z. developed the design and optimization procedure, performed numerical simulation, and analyzed the data under the supervision of H.K.T. and X.S.; Z.Y., J.M. and B.Z. contributed to numerical simulation; W.Z. and X.S. wrote the manuscript, which was reviewed and commented by all the authors.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, W., Yu, Z., Ma, J. et al. Ultraviolet optomechanical crystal cavities with ultrasmall modal mass and high optomechanical coupling rate. Sci Rep 6, 37134 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37134

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37134

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.