Abstract

Mutations disrupting the reading frame of the ~2.4 Mb dystrophin-encoding DMD gene cause a fatal X-linked muscle-wasting disorder called Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). Genome editing based on paired RNA-guided nucleases (RGNs) from CRISPR/Cas9 systems has been proposed for permanently repairing faulty DMD loci. However, such multiplexing strategies require the development and testing of delivery systems capable of introducing the various gene editing tools into target cells. Here, we investigated the suitability of adenoviral vectors (AdVs) for multiplexed DMD editing by packaging in single vector particles expression units encoding the Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 nuclease and sequence-specific gRNA pairs. These RGN components were customized to trigger short- and long-range intragenic DMD excisions encompassing reading frame-disrupting exons in patient-derived muscle progenitor cells. By allowing synchronous and stoichiometric expression of the various RGN components, we demonstrate that dual RGN-encoding AdVs can correct over 10% of target DMD alleles, readily leading to the detection of Becker-like dystrophin proteins in unselected muscle cell populations. Moreover, we report that AdV-based gene editing can be tailored for removing mutations located within the over 500-kb major DMD mutational hotspot. Hence, this single DMD editing strategy can in principle tackle a broad spectrum of mutations present in more than 60% of patients with DMD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), affecting ∼1 in 4,000 newborn boys1, is amongst the most severe and common forms of muscular dystrophies, a heterogeneous group of inherited disorders marked by progressive muscle weakness and wasting2,3. The molecular basis of DMD, known since 1987, features different loss-of-function mutations within the ~2.4 Mb dystrophin-encoding DMD gene (Xp 21.2) (ref. 4). Although duplications and point mutations give rise to this pathology, the vast majority of DMD-causing mutations consists of intragenic deletions, comprising one or more exons5. Of note, genomic defects located in a major mutation prone “hotspot” region, spanning exons 45 through 55, account for more than 60% of the population of patients with DMD5. Regardless of their nature and location, most DMD-causing mutations lead to reading frame disruptions resulting in a lack of dystrophin, an essential musculoskeletal protein. Amongst other functions, this rod-shaped protein is involved in muscle cell stability since it provides a key link between the dystrophin-associated protein complex (DAPC) embedded in the sarcolemma and the actin mesh in the cytoskeleton. Hence, in patients with DMD, dystrophin deficiency compromises the integrity of muscle cells ultimately resulting in progressive skeletal and cardiac myopathy leading to fatality, normally between the second and third decades of life2,6. Despite many research efforts, to date DMD treatments remain palliative and supportive rather than curative2,6,7.

Gene therapy is being pursued as a potential DMD therapeutic option whose benefits may be maximized if combined with pharmacological and cell-based approaches. Notably, the very large size (i.e. ~11 kb) of the full-length DMD coding sequence (CDS) (refs 2 and 6) puts it outside the packaging capacity of most commonly used viral vectors such as that of ∼4.7 kb of recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) particles8. It is also known that in-frame deletions within DMD, resulting in internally truncated dystrophins, give rise to Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD), a less severe form of muscular dystrophy. This observation has led to the investigation of therapeutic interventions based on gene replacement and exon skipping2,6,7. The former entails the delivery of dystrophin lacking non-essential domains (e.g. microdystrophins), while the latter exploits the use of antisense oligonucleotides for interfering with the splicing machinery and prevent the inclusion of reading frame-disrupting exons into the DMD mRNA. Additionally, programmable nuclease-assisted genome editing has been put forward as yet another potential therapeutic modality that, by directly correcting defective DMD loci, assures permanent dystrophin synthesis from their native regulatory elements9,10,11,12,13.

RNA-guided nucleases (RGNs) constitute particularly powerful genome editing tools14,15,16. The most commonly employed RGNs are based on the type II clustered, regularly interspaced, short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-associated Cas9 (CRISPR-Cas9) system from Streptococcus pyogenes. In this binary ribonucleoprotein complex, a single guide RNA (gRNA) addresses the Cas9 nuclease to predefined genomic sequences17. These target sequences consist of 18–20 nucleotides, complementary to the 5′ end of the gRNA, followed by a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM; NGG, in the case of S. pyogenes Cas9) (ref. 17). The Cas9 generates a blunt-ended double-stranded DNA break (DSB) that triggers endogenous DNA repair pathways which are ultimately exploited for achieving permanent and targeted genetic modifications13. In mammalian cells, a major DNA repair pathway is that of non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). This pathway culminates with a direct end-to-end ligation of DNA termini often resulting in the incorporation of small insertions and deletions (indels) (ref. 13).

An appealing feature of RGNs is their versatility for multiplexing purposes. Related to this, it has been shown that expressing two or more gRNAs addressing Cas9 to different genomic sites, enables targeting multiple genes or triggering genomic alterations between pairs of DSBs such as intragenic deletions13,14,18. Of note, proof-of-principle studies have demonstrated that such RGN multiplexes can be employed to remove reading frame-disrupting exons from DMD loci19. These manoeuvres result in the expression of in-frame mRNA transcripts which are translated into shorter, but still functional, dystrophins which are reminiscent of those underlying mild BMD phenotypes. Such multiplexing strategies have been validated in patient-derived myoblasts19,20, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) (ref. 21) and dystrophic Dmdmdx mice22,23,24,25. Of note, experiments performed in iPSCs and human myoblasts have demonstrated that RGN multiplexes can also trigger the deletion of the major DMD mutational hotspot19,20,21. These studies provide a strong rationale for developing DMD therapeutic strategies based on RGN multiplexes. However, more research is needed especially for achieving simultaneous, uniform and efficient introduction of all nuclease components into target cells.

In the present work, we sought to investigate the feasibility and suitability of using “all-in-one” adenoviral vectors (AdVs) for delivering RGN multiplexes designed for removing single or multiple exons from defective DMD alleles. Following AdV transductions of patient-derived muscle progenitor cells, we report that these NHEJ-mediated gene editing strategies result in efficient DMD reading frame restoration and yield readily detectable dystrophin synthesis in muscle cells differentiated from unselected target cell populations. Notably, we demonstrated that “all-in-one” AdVs can mediate the removal of mutations located within the over 500-kb major DMD mutational hotspot allowing for tackling more than 60% of the registered DMD mutations5 via a single viral-based gene editing strategy. Furthermore, we tested side-by-side DMD editing based on “all-in-one” AdV delivery of dual and single RGN complexes. The latter strategies are customized to correct specific DMD mutations via NHEJ-mediated reading frame resetting and DNA-borne exon skipping20. We demonstrate that AdVs encoding single or dual RGN complexes can lead to DMD repair and de novo dystrophin protein synthesis without having to resort to cell selection schemes. Collectively, this study establishes AdVs as a versatile and powerful platform for the delivery of RGN multiplexes into therapeutically relevant cells.

Results

Packaging RGN multiplexes in single AdV particles

We started by investigating the suitability of AdV particles for packaging DNA coding for Cas9 and gRNA pairs targeting intronic DMD sequences. To this end, we selected RGN complexes customized to trigger short- and long-range intragenic DMD excisions after the activation of the NHEJ pathway20. In particular, the gRNA pair gIN52 and gIN53 was designed to induce a short, mutation-specific, DMD excision spanning exon 53. Next to this, the gRNA pair gIN43 and gIN54 was customized to tackle a large range of DMD mutations by triggering DSB formation in introns 43 and 54 flanking the major DMD mutational hotspot. Thus, in the current work, we generated AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53 and AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54 particles containing expression units encoding the aforementioned gRNA pairs and the S. pyogenes Cas9 protein (Fig. 1a). Importantly, these second-generation (i.e. E1- and E2A- deleted) AdVs display apical fiber motifs from adenovirus serotype-50 (F50) (Fig. 1a). In contrast to fibers from prototypic adenovirus serotype-5, that bind the coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor (CAR), the F50 motifs recognize the cellular receptor CD46 instead. This allows fiber-modified AdVs to bypass the absence of CAR on the surface of therapeutically relevant cells, including human muscle progenitor cells and non-muscle cells with myogenic capacity20,26,27,28.

Design and generation of AdVs encoding RNA-guided nuclease components.

(a) Schematic representation of the genome structure of control and DMD-targeting AdVs. The genomes of dual RGN-encoding AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53 and AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54 are depicted in relation to those of single RGN-encoding AdV.Cas9EX51 and AdV.Cas9EX53. The AdV.gRNAS1 and AdV.Cas9, expressing exclusively an irrelevant gRNA and Cas9, respectively, served as controls. The AdV.Cas9EX51 and AdV.Cas9EX53 particles code for Cas9:gEX51 and Cas9:gEX53 complexes, respectively. The target sites of Cas9:gEX51 and Cas9:gEX53 complexes are located in exon 51 and exon 53 of the DMD locus, respectively. AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53 and AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54 deliver a pair of gRNA cassettes together with a Cas9 transcriptional unit. The gRNAs gIN52 and gIN53 address the Cas9 nuclease to DMD sequences in intron 52 and intron 53, respectively; the gRNAs gIN43 and gIN54 target the same nuclease to sequences located in intron 43 and intron 54, respectively. All vectors deployed in this study were isogenic in the sense that they were all assembled on the basis of a second-generation (i.e. E1- and E2A- deleted) AdV backbone coding for chimeric fibers (F50) consisting of basal domains from human adenovirus serotype-5 and apical shaft and knob motifs from human adenovirus serotype-50. Each gRNA expression unit is under the transcriptional control of RNA Pol-III promoter (i.e. U6) and terminator sequences, whereas the Cas9 ORF is under the transcriptional control of the human PGK-1 promoter (PGK) and the simian virus 40 polyadenylation signal (SV40). Ψ, human adenovirus serotype-5 packaging signal; Ad L-ITR and Ad R-ITR, “left” and “right” adenoviral inverted terminal repeat, respectively; RF, reading frame (b) Ratios of genome copies (GC) to infectious units (IU). The GC and IU concentrations in purified preparations of the indicated AdVs were determined by using fluorometric and TCID50 assays, respectively.

After rescuing, propagating and purifying the dual RGN-encoding AdV particles (i.e. AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53 and AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54), we determined that their functional titers and genome copies-to-infectious units ratios were in the range of those of isogenic AdV controls. These controls encode exclusively Cas9, an irrelevant gRNA or encode Cas9 together with a single DMD-targeting gRNA (Fig. 1b). In addition, restriction fragment length analysis was performed on DNA isolated from purified AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53 and AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54 particles. This assay revealed neither large sequence rearrangements nor deletions indicating that both vector genomes were packaged intact (Supplementary Fig. S1). These data demonstrate that tandem gRNA and Cas9 expression units can be stably maintained during the rescue and propagation of AdV particles leading to the packaging of full-length recombinant vector genomes.

“All-in-one” AdV particles achieve DMD repair through short-range, single-exon, excision

To investigate AdV-based DMD editing by targeted single-exon excision, we used the AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53 to transduce patient-derived myoblasts lacking exons 45 through 52 (DMD.Δ45-52). This defective genotype can be tackled by the permanent chromosomal excision of exon 53 since the resulting DNA template generates in-frame mRNA transcripts (Fig. 2a). Of note, approximately 8% to 10% of disrupted DMD reading frames identified in the population with DMD can be fixed by this approach5,29.

“All-in-one” AdV transduction of paired RGNs for DMD repair via short-range intragenic deletions.

(a) DMD repair through NHEJ-mediated exon 53 excisions in DMD.Δ45-52 muscle cells. Genomic deletions spanning exon 45 through exon 52 disrupt the DMD reading frame and yield out-of-frame mRNA transcripts carrying a premature stop codon within exon 53 (red box). RGN multiplexes consisting of Cas9 bound to intron-specific gIN52 and gIN53 gRNAs are designed to trigger the excision of a 1,123-bp DNA segment encompassing exon 53. This strategy is expected to induce the synthesis of a Becker-like dystrophin as splicing of exon 44 to exon 54 generate in-frame mRNA transcripts. gEX53, gRNA targeting Cas9 to a sequence within exon 53; SD, splice donor; SA, splice acceptor. Orange hexagons, CH1 and CH2 actin-binding domain 1; black hexagons, hinges; green boxes, spectrin-like repeats; orange oval, WW domain; blue pentagons, EFH1 and EFH2 hand-regions containing cysteine-rich motifs which, amongst other proteins, bind to β-dystroglycan; green pentagon, ZZ zinc finger domain; grey oval, C-terminal domain. Vertical arrowhead, protein junction formed by the DMD editing procedure. (b) qPCR analysis for determining the frequencies of DMD exon 53 deletion. The qPCR assay was applied on genomic DNA from DMD.Δ45-52 myoblasts transduced with “all-in-one” vector AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53. The DMD.Δ45-52 myoblasts were transduced with AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53 at the indicated multiplicities of infection (MOI). qPCR assays were carried out with primer pairs flanking the RGN-induced intronic junction (solid arrowheads). A primer pair targeting intron 43 sequences (open arrowheads) served as an internal control for determining the amounts of input DNA. MOI, multiplicity of infection; Error bars, standard deviations of technical replicates; ND, not detected. (c) Dystrophin western blot analysis after AdV.Cas9EX53 and AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53 transductions. The DMD.Δ45-52 myoblasts were transduced with AdV.Cas9EX53 and AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53 at multiplicities of infection (MOI) of 25 and 50 IU/cell. Cultures with myotubes differentiated from mock-transduced wild-type myoblasts (WT) served as positive controls. Negative controls were obtained from cultures containing myotubes differentiated from DMD.Δ45-52 myoblasts transduced at an MOI of 12.5 IU/cell with AdV.gRNAS1. After 4 days in differentiation medium, western blot analysis was performed on unselected AdV-transduced muscle cell populations. Tubulin provided for a loading control antigen. E, empty lane.

To start DMD editing experiments, DMD.Δ45-52 myoblasts were either mock-transduced or were transduced with AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53 at MOIs of 25 and 50 IU/cell. At 7 days post-transduction, a qPCR assay designed for quantifying the DNA junctions generated after the simultaneous expression of Cas9:gIN52 and Cas9:gIN53 complexes, revealed that AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53 mediated permanent DMD repair in up to 13% of DMD.Δ45-52 cells (Fig. 2b).

Considering that AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53 transductions did not abolish the differentiation and fusion capacity of gene-edited DMD.Δ45-52 myoblasts, we proceeded to assess the rescue of dystrophin synthesis in DMD muscle cell populations. To this end, parallel transduction experiments were performed in DMD.Δ45-52 myoblasts by deploying AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53, isogenic AdV.Cas9EX53 and, as negative control vector, AdV.gRNAS1. Of note, AdV.Cas9EX53 delivers a single Cas9:gEX53 complex customized to induce DSBs at a sequence in exon 53, which trigger NHEJ in generating indels that disrupt splicing motifs or shift the reading frame to the proper coding sequence. The resulting DNA-borne exon skipping and reading frame resetting events repair the defective DMD locus in DMD.Δ45-52 cells20. After triggering myoblast differentiation, western blot analysis revealed the presence of Becker-like dystrophin proteins in cultures of myotubes whose progenitors had undergone AdV.Cas9EX53 and AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53 transductions (Fig. 2c). As expected, DMD myoblasts exposed to the control vector AdV.gRNAS1 did not yield detectable levels of dystrophin once differentiated into myotubes (Fig. 2c). Importantly, based on the relative intensities of the western blot signals diagnostic for dystrophin, the levels of de novo dystrophin protein synthesis resulting from AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53 transductions were not inferior to those achieved by the isogenic AdV.Cas9EX53 (Fig. 2c).

“All-in-one” AdV particles achieve DMD repair through long-range, multi-exon, excision

To broaden the potential applicability of AdV-based DMD editing, we have investigated the suitability of AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54 for chromosomal removal of sequences framing the major DMD mutational hotspot. To this end, we deployed patient-derived myoblasts with two different DMD genotypes (i.e. DMD.Δ48-50 and DMD.Δ45-52) (Fig. 3a). These and all the other faulty genotypes nested within the major DMD mutational hotspot region can, in principle, be tackled by AdVs encoding Cas9:gIN43 and Cas9:gIN54 complexes since these RGNs generate DSBs at their cognate sequences in intron 43 and intron 54, respectively. The NHEJ-mediated end-to-end ligation of the resulting chromosomal termini, and concomitant excision of the intervening DNA, is expected to rescue dystrophin synthesis as splicing of exon 43 to exon 55 generates in-frame RNA transcripts (Fig. 3a).

“All-in-one” AdV transduction of paired RGNs for DMD repair via long-range intragenic deletions.

(a) DMD repair through NHEJ-mediated long-range, multi-exon, deletion. DMD-causing mutations located in the major DMD mutational hotspot (spanning exon 45 through exon 55) can, in principle, be tackled by a single multiplexing strategy based on the excision of a DNA segment encompassing exon 44 through exon 54. This multi-exon deletion strategy can build on the coordinated action of a pair of RGNs, consisting of Cas9 bound to the intron-specific gIN43 or gIN54 gRNAs. These RGNs are designed to repair the DMD reading frame as the joining of exon 43 to exon 55 is expected to yield in-frame mRNA species coding for an internally truncated Becker-like dystrophin. gEX51, gRNA targeting Cas9 to a sequence within exon 51. Vertical arrowhead, protein junction formed by the DMD editing procedure. For the naming of the dystrophin structural domains see legend of Fig. 2a. (b) qPCR analysis for establishing the frequencies of DMD multi-exon deletions. The qPCR assay was applied on genomic DNA from DMD.Δ48-50 and DMD.Δ45-52 myoblasts transduced with “all-in-one” vector AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54. The DMD.Δ48-50 and DMD.Δ45-52 myoblasts were transduced with AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54 at the indicated multiplicities of infection (MOI). qPCR assays were carried out with primer pairs flanking the expected RGN-induced intronic junction (solid arrowheads). qPCR amplifications with primer pair targeting intron 43 sequences (open arrowheads) provided for an internal control to determining the amounts of input DNA. Error bars, standard deviations of technical replicates; ND, not detected. (c) Dystrophin western blot analysis after AdV.Cas9EX51 and AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54 transductions. The DMD.Δ45-52 and DMD.Δ48-50 myoblasts were transduced with AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54; the DMD.Δ48-50 myoblasts were transduced with AdV.Cas9EX51. The multiplicities of infection (MOI) used are indicated. Cultures with myotubes differentiated from mock-transduced wild-type myoblasts (WT) served as positive controls. Negative controls were obtained from cultures containing DMD.Δ45-52 and DMD.Δ48-50 myotubes whose progenitors had been transduced with AdV.gRNAS1 at an MOI of 12.5 IU/cell. After exposing DMD.Δ45-52 and DMD.Δ48-50 myoblasts to differentiation medium for 4 and 5 days, respectively, western blot analysis was performed on unselected AdV-transduced muscle cell populations. Tubulin provided for a loading control antigen. E, empty lane.

Therefore, we performed DMD editing experiments in which DMD.Δ48-50 and DMD.Δ45-52 myoblasts were either mock-transduced or were transduced with AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54 at MOIs ranging from 5 to 75 IU/cell. At 7 days post-transduction, a PCR assay with primers flanking the expected genomic excision, readily led to the detection of amplicons diagnostic for the de novo generated junction Δ44-54 exclusively in AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54-transduced myoblast populations (Supplementary Fig. S2). Importantly, a qPCR assay analogous to that used for measuring single-exon deletions (Fig. 2b), revealed a clear AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54 dose-dependent increase in DMD editing frequencies in DMD.Δ48-50 and DMD.Δ45-52 target cell populations (Fig. 3b). The fractions of DMD-edited myoblasts ranged from a minimum of 3% to a maximum of 18% (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, these gene correction levels were similar to those achieved in parallel transduction experiments in which isogenic AdV.Cas9EX51 particles were used instead for targeted DMD repair in DMD.Δ48-50 myoblasts (Supplementary Fig. S3). In contrast to AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54, isogenic AdV.Cas9EX51 works analogously to AdV.Cas9EX53 in that it delivers a single RGN complex (i.e. Cas9:gEX51) customized to repair the defective DMD locus via DNA-borne exon skipping and reading frame resetting20. Therefore, this side-by-side comparison of DMD editing following AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54 and AdV.Cas9EX51 transductions, suggests that delivering RGN multiplexes, instead of a single RGN complex, in AdV particles is not, per se, a limiting factor for achieving efficient endogenous DMD repair.

Subsequently, we investigated the capacity of AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54 to induce robust de novo dystrophin synthesis in bulk populations of differentiated myoblasts. To this end, DMD.Δ48-50 and DMD.Δ45-52 myoblasts were transduced with a dose-range of AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54 and, after that, were induced to differentiate. Analogous to previous experiments, parallel transductions with the isogenic vector AdV.Cas9EX51 were carried out in DMD.Δ48-50 myoblasts, whereas transduction with the control vector AdV.gRNAS1 were done in DMD.Δ48-50 and DMD.Δ45-52 myoblasts. Western blot analysis readily established the presence of Becker-like dystrophins in cultures of differentiated myoblasts DMD.Δ48-50 and DMD.Δ45-52 that had been initially exposed to AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54 (Fig. 3c). Consistent with the large sizes of the excised chromosomal DNA fragments, the de novo generated dystrophin variants were smaller than those expressed from differentiated wild-type myoblasts (Fig. 3c). Importantly, in line with the DMD editing frequencies at the DNA level, the amounts of dystrophin molecules induced by AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54 were similar to those achieved by using the isogenic vector AdV.Cas9EX51 (Fig. 3c). As expected, parallel transduction experiments in which the control vector AdV.gRNAS1 was used, did not lead to detectable amounts of dystrophin (Fig. 3c).

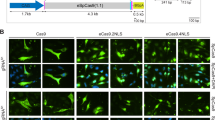

To complement the previous data, myotube cultures parallel to those processed for western blot analysis, were subjected to dual-color immunofluorescence microscopy. This assay permits the simultaneous detection of dystrophin and β-dystroglycan, a key component of the DAPC. Consistent with the western blot results, the immunofluorescence microscopy data confirmed rescue of dystrophin synthesis in DMD.Δ48-50 and DMD.Δ45-52 myotubes whose progenitors had been exposed to AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54 or AdV.Cas9EX51 (Fig. 4). Furthermore, a degree of AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54 dose-dependent increase in dystrophin amounts could be discerned corroborating the data retrieved by qPCR (Fig. 3b). Importantly, co-localization of dystrophin- and β-dystroglycan-specific signals could be detected in DMD-edited myotubes (Fig. 4). These data suggest the stabilization and proper assembly of β-dystroglycan at the plasma membrane, likely owing to its linkage to the cysteine-rich domains of the de novo synthesized dystrophin molecules.

Dystrophin and β-dystroglycan immmunofluorescence microscopy on DMD-edited myotubes.

Immunostainings for dystrophin and β-dystroglycan were carried out in myotubes differentiated from DMD.Δ48-50 and DMD.Δ45-52 myoblasts transduced with the AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54. Each numeral refers to multiplicities of infection (MOI). The same immunostainings were also done in myotubes differentiated from DMD.Δ48-50 myoblasts transduced with AdV.Cas9EX51 at the indicated MOI. Myotubes derived from DMD.Δ48-50 and DMD.Δ45-52 transduced with AdV.gRNAS1 at an MOI 12.5 IU/cell served as negative controls. Myotubes isolated from a healthy donor (WT) and transduced with AdV.gRNAS1 provided for positive controls.

Taken our data together, we demonstrate that DMD editing based on AdVs encoding RGN multiplexes induces robust synthesis of Becker-like dystrophins in unselected muscle cell populations. Moreover, notwithstanding differences specific to each of the experimental settings, namely the use of different gRNAs, our data suggest that AdV delivery of two RGNs can yield DMD repair levels similar to those achieved by using AdV transfer of single, mutation-specific, RGNs.

Discussion

Sequence-specific programmable nucleases have dramatically accelerated progress in genome editing and are opening up alternative therapeutic options for tackling acquired and inherited disorders, including DMD30. Yet, advancing the testing and application of DMD editing requires, amongst other developments, improved methods for delivering the necessary, and often sizable, molecular tools into target cells. The delivery issue is even more critical in the case of multiplexing strategies since these require simultaneous introduction of different nuclease complexes into target cell nuclei13. In this regard, the integration of viral vectors and RGNs, as bona fide gene delivery vehicles and versatile programmable nucleases, respectively, has the potential to facilitate and broaden the applicability of multiplexing strategies for DMD editing in ex vivo and in vivo settings31.

AdVs constitute appealing delivery systems owing to their large packaging capacity, strict episomal nature and fast kinetics of transgene expression in dividing and post-mitotic target cells32,33. Indeed, previous work carried out in our laboratory has shown that AdVs yield high-level and transient expression of transcription activator-like effector nucleases and Cas9 nucleases in clinically relevant cell types, including muscle progenitor cells and non-muscle cells with myogenic capacity20,28,34. In the current work, we have demonstrated that “all-in-one” dual RGN-encoding AdVs trigger short- and long-range removal of DMD segments encompassing out-of-frame sequences. Both of these gene editing strategies resulted in DMD reading frame restoration and ensuing dystrophin detection in target cell populations without the need for implementing expedients to select DMD-edited cells or nuclease-exposed cell fractions. Moreover, the frequencies of DMD repair achieved by AdV delivery of RGN multiplexes for long-range intragenic deletions were similar to those obtained by AdV transfer of single RGNs for mutation-specific reading frame resetting and DNA-borne exon skipping20.

The excision of the large DMD segment encompassing exons 44 through 54, shortens the internal rod-shaped portion of dystrophin composed of a series of spectrin-like repeats interrupted by proline-rich segments called hinges35. This internal dystrophin portion is, to a certain degree, dispensable as indicated by the fact that the vast majority of the in-frame deletions causing BMD are also located between exon 45 and exon 55 (ref. 36). In this regard, large in-frame DMD deletions reducing the length of the rod-shaped portion of dystrophin have been linked to BMD phenotypes that are milder than those caused by certain shorter deletions37,38,39. For instance, it has been shown that extensive in-frame deletions removing hinge 3 (i.e. exons 50–51) correlate with milder BMD phenotypes when compared to smaller deletions that preserve hinge 337. Presumably this is the result of the altered combination of primary amino acid sequences impacting the higher-order structures of dystrophins.

The amenability of RGN multiplexing for inducing exon deletions and thereby rescuing dystrophin synthesis is also supported by a recent cluster of studies involving experiments in the mouse model DMDmdx whose mild dystrophic phenotype is caused by a premature stop codon in Dmd exon 23 (refs. 22, 23, 24, 25). In particular, intramuscular co-injection of a pair of conventional serotype-5 AdVs encoding Cas9 and gRNAs, resulted in the excision of Dmd exon 23 and dystrophin protein synthesis in transduced myofibers22. In other studies, systemic and local co-injections of pairs of rAAVs encoding gRNAs and either S. pyogenes Cas9 or the smaller orthologue Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 (SaCas9), equally led to the excision of Dmd exon 23 and restoration of dystrophin synthesis in transduced striated muscles23,24,25. Together, these studies provided proof-of-concepts for in vivo muscle-directed gene repair based on viral vector delivery of RGN multiplexes. However, conventional serotype-5 AdVs have a reduced tropism for human muscle progenitor cells and non-muscle cells with myogenic capacity26,27, while the limited cargo of rAAVs (i.e. ~4.7 kb) restricts the flexibility with which dual RGN-encoding rAAVs can be constructed (e.g. inclusion of sizable constitutive or muscle-specific promoters). In addition, “all-in-one” rAAVs encoding SaCas9 together with gRNA pairs appeared to yield lower frequencies of targeted DNA manipulations when compared to those resulting from rAAVs encoding SaCas9 and gRNA molecules separately25.

The repair of defective DMD alleles via RGN multiplexing has been further validated in patient-derived myoblasts19,20 and human iPSCs21. In addition, these studies demonstrated that RGN multiplexing can induce large DMD excisions, generating internally truncated, but functional, dystrophins19,20,21. However, the very low efficiencies in deleting these large chromosomal segments achieved by using non-viral delivery methods, required the implementation of selection schemes and clonal analysis for the isolation of DMD-edited cells19,21. In contrast, here we report that generating targeted, long-range, DMD deletions by “all-in-one” AdV transduction of RGN multiplexes, results in the direct, selection-free, detection of de novo dystrophin proteins in bulk target cell populations. The delivery of dual RGN complexes by single AdV particles presumably assures that the various nuclease components are present in target cell nuclei at the same time, in high amounts and at a fixed stoichiometry. The synchronous generation of the paired chromosomal DSBs maximizes the chance that end-to-end ligation of the distal chromosomal termini results in the deletion of the intervening sequence. We showed that dual RGN-encoding AdVs induce short- and long-range genomic deletions correcting over 10% of defective DMD alleles.

Studies in severely dystrophic mouse models indicate that dystrophin amounts as low as 4% of the wild-type level confer a clear improvement in survival and motor function40,41. Hence, if low to moderate levels of dystrophin can equally benefit patients with DMD, therapeutic gene correction will be mostly dependent on delivering in a safe manner gene-edited myogenic cells or gene-editing vector particles to large portions of the striated musculature31.

Towards clinical translation, the use of fiber-modified “all-in-one” AdVs encoding single or dual RGNs will permit testing DMD editing strategies in human muscle progenitor cells and non-muscle cells with myogenic capacity42,43, harboring mutations which are not represented in current animal models44. These experiments are expected to contribute to assessing intended and unwanted genome-modification events caused by the interaction of specific DMD editing reagents with the human genome. The present research should also profit from and build upon the development of sensitive and unbiased assays for genome-wide DSB detection45,46.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that AdVs encoding RGN multiplexes designed to remove a single exon or the major DMD mutational hotspot offer a flexible and robust NHEJ-mediated DMD repair strategy. This research is expected to facilitate the screening and testing of genetic therapies involving the in situ repair of defective DMD loci in patient-own cells.

Materials and Methods

Cells

The human cervix carcinoma HeLa cells (American Type Culture Collection) and the E1- and E2A-complementing AdV packaging cell line PER.E2A were cultured as previously described20,47.

The origin of and the cultures conditions for the human myoblasts harboring DMD intragenic deletions Δ48-50 or Δ45-52 or the wild-type DMD genotype, herein referred to as DMD.Δ48-50, DMD.Δ45-52 and WT, respectively, have also been detailed elsewhere48. The various cell batches used in this study were mycoplasma-free.

gRNAs design and validation

The design and validation of the gRNAs, whose expression is controlled by the human U6 RNA polymerase III promoter, have been described before20. The gRNA cassettes gI43, gI52, gI53 and gI54.2 (hereinafter named gIN43, gIN52, gIN53 and gIN54, respectively) target sequences present in DMD introns 43, 52, 53, and 54, respectively. The gRNA paired cassettes gIN52/gIN53 and gIN43/gIN54 were employed to trigger short- and long-range intragenic DMD excisions, respectively. The individual gRNA cassettes gE51.2 and gE53 (hereinafter named gEX51 and gEX53, respectively), used as references for DMD repair based on the delivery of single RGN complexes, target DMD sequences located in exon 51 and 53, respectively.

The DNA target sequences of each gRNA are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Plasmids

Standard recombinant DNA techniques were applied for the construction of the various AdV transfer constructs and qPCR standard-curve plasmids49. To generate the AdV transfer plasmid AU53_pAd.Shu.gI52.gI53.PGK.Cas9.SV40pA, plasmids pLV.gI52 and pLV.gI53 (ref. 20) were digested with XhoI (Thermo Scientific) and the resulting fragments, containing the gI52 and gI53 expression units, were isolated and ligated in two consecutive steps into the Eco105I and Eco147I restriction sites of pAdSh.PGK.Cas9 (Addgene plasmid #58253) (ref. 28), respectively. Next, the full-length E1- and E2A-deleted (i.e. second-generation) fiber-modified AdV molecular clone AU57_pAdVΔ2gI52.gI53.PGK.Cas9.F50 was assembled via homologous recombination (HR) after the transformation of E. coli cells BJ5183pAdEasy-2.50 (ref. 50) with the MssI-treated AU53_pAd.Shu.gI52.gI53.PGK.Cas9.SV40pA, as detailed elsewhere50,51. Similarly, AdV transfer plasmid AU04_pAd.Shu.gI54.gI43.PGK.Cas9.SV40pA was obtained by cloning gI43 and gI54 expression units from XhoI-treated pLV.gI43 and pLV.gI54.2 (ref. 20) into the Eco147I and Eco105I restriction sites of pAdSh.PGK.Cas9 (Addgene plasmid #58253) (ref. 28), respectively. The resulting AdV transfer plasmid was used for the construction of the E1- and E2A-deleted fiber-modified AdV molecular clone AU08_pAdVΔ2gI54.gI43.PGK.Cas9.F50, according to the protocol detailed elsewhere50,51.

The construction of the AdV molecular clones AU10_pAdVΔ2gE53.P.Cas9.F50, AU12_pAdVΔ2gE51.2.P.Cas9.F50 and pAdVΔ2P.Cas9.F50 used as molecular weight references in the structural analysis of AdV genomes, have been described before refs 20 and 28.

To generate the standard-curve plasmids for the qPCR assays, genomic DNA from cell populations containing RGN-induced DMD deletions, were subjected to PCR for amplifying DNA sequences encompassing the de novo generated junctions. The primer sequences, the PCR mixture compositions and the cycling parameters are specified in the Supplementary Tables S2 and S3. Agarose gel electrophoresis in 1× TAE buffer was performed for the detection of the resulting PCR products. Next, PCR amplicons were purified using the JETquick Gel Extraction Spin kit (Genomed), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Subsequently, purified PCR products were cloned into the pJET1.2/blunt backbone using the CloneJET PCR cloning Kit (Thermo Scientific), according the manufacturer’s instructions. These maneuvers gave rise to plasmids AV31_jDEL.I52-I53 and AV24_jDEL.I43-I54. The structural integrity of the generated plasmids was assessed by restriction fragment length analysis. The nucleotide sequences of the inserts were confirmed by Sanger sequencing (BaseClear, Leiden, the Netherlands). Similarly, conventional recombinant DNA techniques were applied to generate AL05_pDMD. This construct, containing DNA sequences from DMD intron 43, was used for generating standard curves for the quantification of a control genomic region via qPCR assays. The complete DNA sequence of AL05_pDMD is presented in Supplementary Table S4.

Production and characterization of Adenoviral vectors

The AdV molecular clones AU57_pAdVΔ2gI52.gI53.PGK.Cas9.F50 and AU08_pAdVΔ2gI54.gI43.PGK.Cas9.F50 were used for the production of the fiber-modified E1- and E2A- deleted AdVs AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53 and AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54, respectively. The procedures used to generate, purify and titrate these AdVs have been described in detail before28,51. The generation and characterization of the fiber-modified E1- and E2A-deleted AdVs AdVΔ2P.Cas9.F50, AdVΔ2P.Cas9.gE53.F50, AdVΔ2P.Cas9.gE51.2.F50 (herein referred as AdV.Cas9, AdV.Cas9EX53, AdV.Cas9EX51, respectively), as well as the negative control vector AdV Δ2U6.gRNAS1.F50 (herein named AdV.gRNAS1) have been described elsewhere20,28. The titers of the purified AdV stocks expressed in genome copies per ml (GC/ml) and infectious units per ml (IU/ml) together with their ratios are listed in Supplementary Table S5. The former and latter titers were determined by using the QuantiT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen) and TCID50 assays, respectively, as described elsewhere50.

The structural integrity of packaged AdV genomes was assessed by restriction fragment length analysis (i.e. Kpn2I and BglII) of DNA isolated from the respective purified particles as described before28,33,51.

Transduction experiments

Gene editing experiments were initiated by seeding DMD.Δ45-52 and DMD.Δ48-50 myoblasts at a density of 3×104 cells per well of 24-well plates (Greiner Bio-One) pre-coated with a 0.1% (w/v) gelatin solution (Sigma-Aldrich). The next day, DMD.Δ45-52 myoblasts were exposed in 500-μl volumes to different MOIs of AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53, whereas DMD.Δ45-52 and DMD.Δ48-50 myoblasts were exposed to different MOIs of AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54. DMD.Δ48-50 myoblasts transduced with AdV.Cas9EX51 served as a reference for DMD reading frame repair by a gene editing approach based on the delivery of a single RGN complex. Negative controls were provided by mock-transduced DMD.Δ45-52 and DMD.Δ48-50 myoblasts. Three days post-transduction, the inocula were discarded and the cells were transferred into cell culture vessels containing regular growth medium. Seven days post-transduction, genomic DNA was isolated and the intragenic DMD deletion frequencies were determined by qPCR assays as indicated below. The frequencies of targeted DSB formation in AdV.Cas9EX51-transduced DMD.Δ48-50 myoblasts were assessed by TIDE analysis as indicated elsewhere20,52.

qPCR assays

The frequencies of DMD intragenic deletions were assessed by qPCR assays. To this end, total cellular DNA from mock- or AdV-transduced cells was extracted at 7 days post-transduction by using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Next, 5 ng of genomic DNA were diluted in 20-μl reaction mixtures with 1 × iQTM SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) and 150 nM of each primer. The primers were designed with the aid of the open source Primer3 program (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/) and their sequences are specified in the Supplementary Table S6. All samples were amplified in triplicate. Parallel qPCR amplifications targeting DNA sequences located in intron 43 of the DMD locus provided for internal controls. The amplifications were carried in a CFX ConnectTM Real-Time System (Bio-Rad), according to the thermal cycling protocols indicated in Supplementary Table S7. After each run, the baseline thresholds and the estimated copy numbers were auto-calculated by Bio-Rad CFX Manager 3.1. The copy numbers of genomic short- and long-range DMD deletions were determined on the basis of standard curves using serial dilutions (ranging from 2.26 × 10 to 2.32 × 104 copies) of AV31_jDEL.I52-I53 and AV24_jDEL.I43-I54 plasmids, respectively. For the internal control samples, standard curves were made on the basis of serial dilutions (ranging from 7.56 × 10 through 7.56 × 104 copies) of reference plasmid AL05_pDMD. Finally in order to estimate deletion frequencies, the copy numbers of genomic deletions were normalized, on a per-sample basis, for the copy numbers of the internal control. The data were plotted with the aid of Microsoft Office Excel 2010.

Qualitative detection of long-range DMD deletions

Genomic DNA extracted from mock- or AdV-transduced cells was subjected to PCR assays for amplifying DNA fragments spanning the expected DNA junctions formed after the coordinated action of RGN pairs. The primer sequences, PCR mixture compositions and cycling parameters are listed in the Supplementary Tables S2 and S3. Agarose gel electrophoresis in 1× TAE buffer was performed for the detection of the resulting PCR products.

Western blot analysis

The DMD.Δ45-52 and DMD.Δ48-50 myoblasts were first seeded and transduced as indicated above (Transduction experiments). Next, DMD.Δ45-52 myoblasts were exposed to different MOIs of AdV.Cas9IN52.IN53, whereas DMD.Δ45-52 and DMD.Δ48-50 myoblasts were exposed to different MOIs of AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54. References were provided by parallel transductions of DMD.Δ45-52 and DMD.Δ48-50 myoblasts with a dose-range of AdV.Cas9EX53 and AdV.Cas9EX51, respectively. Cultures containing myotubes derived from mock-transduced wild-type myoblasts served as positive controls. Negative controls were provided by exposing DMD.Δ45-52 and DMD.Δ48-50 cells at an MOI of 12.5 IU/cell to control vector AdV.gRNAS1.

Three days post-transduction, the various inocula were replaced by mitogen-poor differentiation medium to trigger myoblast differentiation and fusion. The differentiation medium consisted of phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 0.05% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 mM creatine monohydrate (Sigma-Aldrich), 50 μg/ml uridine (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 ng/ml pyruvic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), 1× Penicillin/Streptomycin (Life Technologies) and 1× GlutaMax (Life Technologies). After 4 to 5 days in differentiation medium, the myotube-containing cultures were lysed by incubation on ice for 30 min in 50 μl of RIPA buffer (Thermo Scientific) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmpleteTM Mini, Sigma-Aldrich). Next, the cell lysates were diluted in 4× sample buffer and 20× reducing agent (both from Bio-Rad) and incubated at 95 °C for 5 min. Protein samples and 15 μl of HiMarkTM Prestained Protein Standard (Thermo Scientific) were loaded in a 3–8% CriterionTM XT Tris-Acetate precast gel (Bio-Rad). The gel was placed in an ice-cooled CriterionTM Cell and was run in XT Tricine running buffer (both from Bio-Rad) first for 1 h at 75 V (0.07 A) and then for 2.5 h at 150 V (0.12 A). Subsequently, the resolved proteins were transferred with the aid of a Trans-Blot® TurboTM Midi PVDF pack and a Trans-Blot TurboTM system (both from Bio-Rad), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations for high molecular-weight proteins (2.5 A, 25 V, 10 min). The PVDF membrane was blocked overnight in TBS with 0,05% (v/v) Tween 20 (TBST, Thermo Scientific) supplemented with 5% (w/v) Elk milk (Campina) and subsequently was washed in TBST. Next, the membrane was incubated with a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against dystrophin (ab15277; abcam) or against α/β Tubulin (CST #2148) diluted in TBST with 5% (w/v) Elk milk. After an overnight incubation period at 4 °C, the membrane was washed in TBST and incubated for 4 h at 4 °C with an anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (IgG-HRP; Santa Cruz) diluted in TBST. Proteins were detected by using horseradish peroxidase substrate PierceTM ECL2 (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer’s specifications with the aid of Super RX-N X-Ray film (Fujifilm).

The schematic representation of the Becker-like dystrophin molecules and their respective molecular weights resulting from AdV-based DMD editing procedures involving short- and long-range deletions were assembled with the aid of the eDystrophin website (http://edystrophin.genouest.org/) (ref. 53).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

DMD.Δ45-52 and DMD.Δ48-50 myoblasts were seeded and transduced with AdV.Cas9IN43.IN54 as indicated above (Transduction experiments). Cultures of differentiated wild-type myoblasts that had been transduced with control vector AdV.gRNAS1 at an MOI of 50 IU/cell served as positive controls for dystrophin immunodetection assays, whereas exposing DMD.Δ45-52 and DMD.Δ48-50 myoblasts to the same vector at an MOI of 12.5 IU/cell provided for negative controls. Cultures of differentiated DMD.Δ48-50 myoblasts that had been transduced with different MOIs of AdV.Cas9EX51 served as additional reference samples.

Three days post-transduction, myoblast differentiation and fusion were triggered by adding mitogen-poor medium, as indicated above (western blot analysis). The myotube-containing cultures of myoblasts with wild-type, DMD.Δ45-52 and DMD.Δ48-50 genotypes were stained as described elsewhere20 after 3, 4 and 5 days in differentiation medium, respectively. The applied primary antibodies were a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against the C-terminus of dystrophin (ab15277; abcam) and the NCL-b-DG mouse monoclonal antibody specific for β-dystroglycan (clone 43DAG1/8D5; Novocastra).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Maggio, I. et al. Adenoviral vectors encoding CRISPR/Cas9 multiplexes rescue dystrophin synthesis in unselected populations of DMD muscle cells. Sci. Rep. 6, 37051; doi: 10.1038/srep37051 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Mendell, J. R. et al. Evidence-based path to newborn screening for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann. Neurol. 71, 304–313 (2012).

Guiraud, S. et al. The Pathogenesis and Therapy of Muscular Dystrophies. Annu. Rev. Genomics. Hum. Genet. 16, 281–308 (2015).

Cohn, R. D. & Campbell, K. P. Molecular basis of muscular dystrophies. Muscle Nerve 23, 1456–1471 (2000).

Hoffman, E. P., Brown, R. H. Jr. & Kunkel, L. M. Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell 51, 919–928 (1987).

Bladen, C. L. et al. The TREAT-NMD DMD Global Database: analysis of more than 7,000 Duchenne muscular dystrophy mutations. Hum. Mutat. 36, 395–402 (2015).

Guiraud, S., Chen, H., Burns, D. T. & Davies, K. E. Advances in genetic therapeutic strategies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Exp. Physiol. 100, 1458–1467 (2015).

Konieczny, P., Swiderski, K. & Chamberlain, J. S. Gene and cell-mediated therapies for muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve 47, 649–663 (2013).

Chen, X. & Gonçalves, M. A. Engineered viruses as genome editing devices. Mol. Ther. 24, 447–457 (2016).

Ousterout, D. G. et al. Reading frame correction by targeted genome editing restores dystrophin expression in cells from Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients. Mol. Ther. 21, 1718–1726 (2013).

Li, H. L. et al. Precise correction of the dystrophin gene in duchenne muscular dystrophy patient induced pluripotent stem cells by TALEN and CRISPR-Cas9. Stem Cell Reports 4, 143–154 (2015).

Ousterout, D. G. et al. Correction of dystrophin expression in cells from Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients through genomic excision of exon 51 by zinc finger nucleases. Mol. Ther. 23, 523–532 (2015).

Gaj, T., Gersbach, C. A. & Barbas, C. F. 3rd. ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends. Biotechnol. 31, 397–405 (2013).

Maggio, I. & Gonçalves, M. A. Genome editing at the crossroads of delivery, specificity, and fidelity. Trends. Biotechnol. 33, 280–291 (2015).

Cong, L. et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819–823 (2013).

Mali, P. et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science 339, 823–826 (2013).

Jinek, M. et al. RNA-programmed genome editing in human cells. eLife 2, e00471 (2013).

Jinek, M. et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337, 816–821 (2012).

Canver, M. C. et al. Characterization of genomic deletion efficiency mediated by clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 nuclease system in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 21312–21324 (2014).

Ousterout, D. G., Kabadi, A. M., Thakore, P. I., Majoros, W. H. & Reddy, T. E. Multiplex CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing for correction of dystrophin mutations that cause Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat. Comm. 6, 6244 (2015).

Maggio, I. et al. Selection-free gene repair after adenoviral vector transduction of designer nucleases: rescue of dystrophin synthesis in DMD muscle cell populations. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 1449–1470 (2016).

Young, C. S. et al. A Single CRISPR-Cas9 Deletion Strategy that Targets the Majority of DMD Patients Restores Dystrophin Function in hiPSC-Derived Muscle Cells. Cell Stem Cell 18, 533–540 (2016).

Xu, L. et al. CRISPR-mediated Genome Editing Restores Dystrophin Expression and Function in mdx Mice. Mol. Ther. 24, 564–569 (2016).

Long, C. et al. Postnatal genome editing partially restores dystrophin expression in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy. Science 351, 400–403 (2016).

Nelson, C. E. et al. In vivo genome editing improves muscle function in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Science 351, 403–407 (2016).

Tabebordbar, M. et al. In vivo gene editing in dystrophic mouse muscle and muscle stem cells. Science 351, 407–411 (2016).

Gonçalves, M. A. et al. Transduction of myogenic cells by retargeted dual high-capacity hybrid viral vectors: robust dystrophin synthesis in duchenne muscular dystrophy muscle cells. Mol. Ther. 13, 976–986 (2006).

Knaän-Shanzer, S. et al. Endowing human adenovirus serotype 5 vectors with fiber domains of species B greatly enhances gene transfer into human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 23, 1598–1607 (2005).

Maggio, I. et al. Adenoviral vector delivery of RNA-guided CRISPR/Cas9 nuclease complexes induces targeted mutagenesis in a diverse array of human cells. Sci. Rep. 4, 5105 (2014).

Aartsma-Rus, A. et al. Theoretic applicability of antisense-mediated exon skipping for Duchenne muscular dystrophy mutations. Hum. Mutat. 30, 293–299 (2009).

Prakash, V., Moore, M. & Yáñez-Muñoz, R. J. Current progress in therapeutic gene editing for monogenic diseases. Mol. Ther. 24, 465–474 (2016).

Maggio, I., Chen, X. & Gonçalves, M. A. F. V. The emerging role of viral vectors as vehicles for DMD gene editing. Genome Med. 8, 59 (2016).

Gonçalves, M. A. & de Vries, A. A. Adenovirus: from foe to friend. Rev. Med. Virol. 16, 167–186 (2006).

Crystal, R. G. Adenovirus: the first effective in vivo gene delivery vector. Hum. Gene Ther. 25, 3–11 (2014).

Holkers, M. et al. Differential integrity of TALE nuclease genes following adenoviral and lentiviral vector gene transfer into human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e63 (2013).

Koenig, M., Monaco, A. P. & Kunkel, L. M. The complete sequence of dystrophin predicts a rod-shaped cytoskeletal protein. Cell 53, 219–228 (1988).

Tuffery-Giraud, S. et al. Genotype-phenotype analysis in 2,405 patients with a dystrophinopathy using the UMD-DMD database: a model of nationwide knowledgebase. Hum. Mutat. 30, 934–945 (2009).

Carsana, A. et al. Analysis of dystrophin gene deletions indicates that the hinge III region of the protein correlates with disease severity. Ann. Hum. Genet. 69, 253–259 (2005).

Nakamura, A. et al. Follow-up of three patients with a large in-frame deletion of exons 45-55 in the Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) gene. J. Clin. Neurosci. 15, 757–763 (2008).

Taglia, A. et al. Clinical features of patients with dystrophinopathy sharing the 45-55 exon deletion of DMD gene. Acta Myol. 34, 9–13 (2015).

van Putten, M. et al. Low dystrophin levels increase survival and improve muscle pathology and function in dystrophin/utrophin double-knockout mice. FASEB J. 27, 2484–2495 (2013).

Li, D., Yue, Y. & Duan, D. Marginal level dystrophin expression improves clinical outcome in a strain of dystrophin/utrophin double knockout mice. PLoS One 5, e15286 (2010).

Briggs, D. & Morgan, J. E. Recent progress in satellite cell/myoblast engraftment – relevance for therapy. FEBS J. 280, 4281–4293 (2013).

Negroni, E. et al. Invited review: Stem cells and muscle diseases: advances in cell therapy strategies. Neuropathol. App. Neurobiol. 41, 270–287 (2015).

McGreevy, J. W., Hakim, C. H., McIntosh, M. A. & Duan, D. Animal models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: from basic mechanisms to gene therapy. Dis. Model. Mec. 8, 195–213 (2015).

Wu, X., Kriz, A. J. & Sharp, P. A. Target specificity of the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Quant. Biol. 2, 59–70 (2014).

Hendel, A., Fine, E. J., Bao, G. & Porteus, M. H. Quantifying on- and off-target genome editing. Trends Biotechnol. 33, 132–140 (2015).

Havenga, M. J. et al. Serum-free transient protein production system based on adenoviral vector and PER.C6 technology: high yield and preserved bioactivity. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 100, 273–283 (2008).

Mamchaoui, K. et al. Immortalized pathological human myoblasts: towards a universal tool for the study of neuromuscular disorders. Skelet. Muscle 1, 34 (2011).

Sambrook, J. F. & Russell, D. W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 3rd Ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, NY (2001).

Janssen, J. M., Liu, J., Skokan, J., Gonçalves, M. A. & de Vries, A. A. Development of an AdEasy-based system to produce first- and second-generation adenoviral vectors with tropism for CAR- or CD46-positive cells. Gene Med. 15, 1–11 (2013).

Holkers, M., Cathomen, T. & Gonçalves, M. A. Construction and characterization of adenoviral vectors for the delivery of TALENs into human cells. Methods 69, 179–187 (2014).

Brinkman, E. K., Chen, T., Amendola, M. & van Steensel, B. Easy quantitative assessment of genome editing by sequence trace decomposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, e168 (2014).

Nicolas, A. et al. Assessment of the structural and functional impact of in-frame mutations of the DMD gene, using the tools included in the eDystrophin online database. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 7, 45 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Kamel Mamchaoui (Sorbonne Universités, Center for Research in Myology, Paris, France) and Vincent Mouly (Center for Research in Myology, UMRS 974 UPMC-INSERM, FRE 3617 CNRS, Paris, France) for providing the human myoblasts with wild-type and DMD exon deletion genotypes. The authors are also thankful to Joop Wiegnant for his technical assistance with the immunofluorescence microscopy, Tobias Messemaker for his assistance with the qPCR technique and Rob Hoeben for his critical reading of the manuscript (all from the Department of Molecular Cell Biology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands). This work was supported by the Dutch Prinses Beatrix Spierfonds [W.OR11–18] and the French AFMTéléthon [grant number 16621]. Xiaoyu Chen is the recipient of a Ph.D. research grant from the China Scholarship Council-Leiden University Joint Scholarship Programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.M. and M.A.F.V.G. conceived and designed the experiments; J.L. and J.M.J. generated and validated reagents and tools; J.M.J., setup and validated the western blot assay; X.C. provided technical assistance; I.M., validated the assays and performed the experiments; I.M., J.M.J. and M.A.F.V.G., analyzed the data; I.M. and M.A.F.V.G., wrote the paper. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Maggio, I., Liu, J., Janssen, J. et al. Adenoviral vectors encoding CRISPR/Cas9 multiplexes rescue dystrophin synthesis in unselected populations of DMD muscle cells. Sci Rep 6, 37051 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37051

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37051

This article is cited by

-

Production of Duchenne muscular dystrophy cellular model using CRISPR-Cas9 exon deletion strategy

Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry (2023)

-

CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Gene Therapy in Neurological Disorders

Molecular Neurobiology (2022)

-

Construction of adenovirus vectors simultaneously expressing four multiplex, double-nicking guide RNAs of CRISPR/Cas9 and in vivo genome editing

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Integrating gene delivery and gene-editing technologies by adenoviral vector transfer of optimized CRISPR-Cas9 components

Gene Therapy (2020)

-

Creation of Dystrophin Expressing Chimeric Cells of Myoblast Origin as a Novel Stem Cell Based Therapy for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

Stem Cell Reviews and Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.