Abstract

Lanthanide (Ln(III)) complexes form an important class of highly efficient luminescent materials showing characteristic line emission after efficient light absorption by the surrounding ligands. The efficiency is however lowered by back energy transfer from Ln(III) ion to the ligands, especially at higher temperatures. Here we report a new strategy to reduce back energy transfer losses. Nonanuclear lanthanide clusters containing terbium and gadolinium ions, TbnGd9−n clusters ([TbnGd9−n(μ-OH)10(butylsalicylate)16]+NO3−, n = 0, 1, 2, 5, 8, 9), were synthesized to investigate the effect of energy transfer between Tb(III) ions on back energy transfer. The photophysical properties of TbnGd9−n clusters were studied by steady-state and time-resolved spectroscopic techniques and revealed a longer emission lifetime with increasing number of Tb(III) ions in TbnGd9−n clusters. A kinetic analysis of temperature dependence of the emission lifetime show that the energy transfer between Tb(III) ions competes with back energy transfer. The experimental results are in agreement with a theoretical rate equation model that confirms the role of energy transfer between Tb(III) ions in reducing back energy transfer losses. The results provide a new strategy in molecular design for improving the luminescence efficiency in lanthanide complexes which is important for potential applications as luminescent materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Energy transfer (ET) plays a major role in various molecular photofunctional systems such as fluorescent biosensors1,2,3, photon upconverters4,5,6, and organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs)7,8,9. The efficiency of ET is dependent on the distance between a donor and an acceptor with maximum effective range of 1 nm (in Dexter’s mechanism)10 or 10 nm (in Förster’s mechanism)11. Distance sensitivity is important in fluorescent biosensors since the efficiency of ET between a target biomolecule and a sensor changes according to the distance, allowing biological activities to be monitored through spectroscopic examination12. Closely assembled chlorophylls in a photosystem prompt fast ET and efficiently deliver the energy obtained through absorption of sunlight to a photosynthetic center13,14,15. In organic photovoltaics, ET between “energy relay dyes” and sensitizing dyes has been utilized to extend the absorption region for improvement of power conversion efficiency16,17. Photofunctional systems have been extensively studied in many scientific fields including chemistry, physics, and biology.

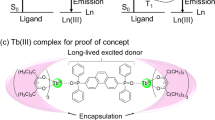

Effective use of energy transfer is also seen in luminescent lanthanide (Ln(III)) complexes, and the process is known as photosensitized energy transfer (PSET). The unique photophysical properties of Ln(III) ions include spectrally fixed, sharp, and long-lived luminescence arising from their characteristic 4f-4f transition18,19,20,21. However, efficient luminescent materials based on Ln(III) ions require photosensitization because of the small absorption coefficient of 4f-4f transitions. Photosensitization can be realized e.g. through energy transfer from organic ligands with a large ab-sorption coefficient (acting as an antenna), leading to intense lanthanide luminescence18,22,23. Much interest has therefore been shown in these Ln(III) complexes for their potential applications to luminescent materials such as those used in bioassays, spectral converters, and electroluminescent devices24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. PSET efficiency is qualitatively known to be high when the energy level of an excited triplet state (T1) of a ligand is slightly higher than the (emitting) excited level of an Ln(III) ion. On the other hand, when T1 energy is too close, the reverse process of PSET, back energy transfer (BET), occurs32,33,34. Optimal excited state energies have been focused on in Ln(III) complexes to suppress BET and achieve high luminescence efficiency.

Green-luminescent Tb(III) complexes have been one of the most frequently reported examples of Ln(III) complexes with BET29,33,34,35,36,37. Experimental studies have revealed that the energy gap between the emitting level of Tb(III) ion (5D4 state) and T1 state of less than 1850 cm−1 promotes fast BET and low luminescence efficiency34,37,38. Consequently, Tb(III) complexes with high luminescence efficiency use organic ligands with high T1 state energy and therefore even higher singlet excited (S1) state energy, leading to absorption range shorter than 350 nm34,39,40. Expanding this range to a longer wavelength while maintaining high luminescence efficiency leads to a larger degree of freedom in molecular design, allowing incorporation of functionality, such as sensing, chirality, and self-assembly. A radically new strategy is required to suppress BET.

Herein, we propose a new method for suppressing BET in Tb(III) complexes: ET between Tb(III) ions (TbET). Photophysical processes are based on competitive kinetics41,42. Since both BET and TbET from a Tb(III) ion occur from the same 5D4 excited level, these two processes are competitive. When the contribution of TbET dominates over BET, BET is suppressed. The contribution of TbET can be increased by reducing the distance between Tb(III) ions to maximize the rate of TbET. An Ln(III) cluster would therefore be the best candidate because it consists of a core of oxygen-bridged Ln(III) ions, and hence the distance between Ln(III) ions is very short, usually about 3.7 Å43,44,45,46,47,48,49. We previously reported opto-magnetic properties of a nonanuclear Tb(III) cluster50,51. It was found that the structural features of this cluster, especially the closely assembled Tb(III) ions and the strong interaction between them, enhances the opto-magnetic property. The cluster is an ideal model to investigate the relationship between BET and TbET and to demonstrate the role of TbET in suppressing BET.

In this study, we introduced Gd(III) ions to nonanuclear Tb(III) clusters in order to investigate the relationship between TbET and luminescence efficiency (Fig. 1a). The energy level of an excited state of Gd(III) ions is high (>31500 cm−1), allowing Gd(III) ions to act as spacers between Tb(III) ions to modulate the TbET processes in otherwise identical clusters. A detailed theory on how TbET can lead to suppression of BET in a nonanuclear Tb(III) cluster model is given in the “Theoretical Background” section. Novel nonanuclear Ln(III) clusters containing Tb(III) and Gd(III) [TbnGd9−n(μ-OH)10(butylsalicylate)16]+NO3− (n = 0, 1, 2, 5, 8, 9) (referred to as “TbnGd9−n clusters”) were synthesized by complexation reaction of Tb(III)/Gd(III) nitrate salt and butylsalicylate. Their characteristic structures were evaluated using FAB-MS, XRD, and X-ray single crystal analysis. Emission spectroscopy, determination of quantum yield, and emission lifetime measurements were performed for the clusters in a chloroform solution. Temperature dependency of emission lifetimes was also determined for estimation of the activation energy of BET. The fundamental photophysics of Ln(III) clusters and their potential as new class of highly efficient luminescent materials are presented in this report.

(a) Nonanuclear Tb(III) cluster (Tb9 cluster). (b) Labeling of Tb9 cluster. The center Tb(III) ion is denoted Tb9, and the Tb(III) ions in the outer unit are denoted Tbm (m = 1–8). (c) Energy transfer between Tbm and butylsalicylate ligand (only one ligand is depicted for clarity). (d) Energy transfer between Tb(III) ions from the point of view of Tb1 separated by 3.65 Å, (e) by 5.10 Å, (f) 5.64 Å, and (g) 7.10 Å. The same processes apply for all other Tbm. (h) Energy transfer between Tb(III) ions from the point of view of Tb9. The energy transfer rate constant is defined as kTbET for two Tb(III) ions separated by 3.65 Å, and other Tb(III) ion pairs are defined relative to this rate constant according to Förster’s mechanism.

Results and Discussion

Theoretical Background

The theoretical background of the concept that back energy transfer (BET) can be suppressed using energy transfer between Tb(III) ions (TbET) in a nonanuclear Tb(III) cluster is provided in this section by using rate equations. The kinetic energy transfer processes in Tb9 clusters50 is depicted in Fig. 1b–h. The energy transfer processes in the cluster include photosensitized energy transfer (PSET), BET, and TbET. Although the closest Tb(III)-Tb(III) pair is less than 4 Å where multipolar and exchange interactions may contribute to the energy transfer rate52, calculation of this contribution does not significantly affect the results and conclusion of this section (see Supplementary Information S2 and Table S1). Therefore for the sake of discussion, the energy transfer rate constant between the closest pair of Tb(III) ions was defined as kTbET and the transfer rates for the other pairs were calculated relative to kTbET based on the simplest R−6 distance dependence of the dipole-dipole Förster mechanism. Tb(III) ions in the outer unit (Tbm, m = 1, 2, …, 8) are involved in PSET and BET with their coordinated butylsalicylate ligands. On the other hand, the center Tb(III) ion (Tb9) is coordinated only by oxygen atoms and is isolated from PSET and BET. The population density of Tb9 is solely dependent on the cycle of repetitive TbET to and from Tb(III) ions in the outer unit Tbm (energy migration). Based on these considerations, a system of differential equation in matrix form (Equation (1)) models the excited state dynamics of Tb9 clusters:

where X(t) is the vector of population density of an excited singlet state (S1(t)), excited triplet state (T1(t)), excited Tb(III) ions in the outer unit (Tbm(t), m = 1, 2, …, 8), and the center Tb(III) ion (Tb9(t)) as shown in Equation (2)

A is the matrix of constants that characterizes the relationship between dynamics of each species and other species in Tb9 cluster and is given in the following equation:

where

kisc, kr, knr, kPSET, kBET, and kTbET are defined as intersystem-crossing, radiative, nonradiative, PSET, BET, and TbET rate constants, respectively. The subscript indicates a species in a Tb9 cluster. Finally, vector J(t) represents the input function of each species in Tb9 cluster:

The excited state decay dynamics after short-pulse excitation were solved using Dirac’s delta function, and the quantum yield (steady-state excitation) was determined by using constants (Supplementary Information S3). In this calculation, the ground state population density is approximated as always being constant, and doubly excited Tb9 clusters are ignored because excitation with reasonably low pump intensity (under 20 W mm−2) is being considered41. The population density of S1(t) (excited singlet state) after excitation is normalized to unity.

Figure 2 shows the calculated decay curve of the population density of Tb9 cluster following a short-pulse excitation for kTbET = 0 s−1 (absence of TbET: blue line) or kTbET = 50000 s−1 (presence of TbET: red line) in the presence of BET. The other rates krS1 + knrS1 = 3.4 × 108 s−1, kiscs1 = 7.5 × 108 s−1, krT1 + knrT1 = 15000 s−1, and krTb = knrTb = 400 s−1 were chosen from previous reports53,54. The values of kPSET and kBET are arbitrary and do not affect the qualitative result. For clarity of the results, kPSET = 6000 s−1 and kBET = 3000 s−1 were chosen. The lifetime of collective Tb(III) ions (Tb1(t) + Tb2(t) + … + Tb9(t)) is extended to τcalc = 720 μs in the presence of TbET compared to τcalc = 685 μs in the absence of TbET. The decay curves of the T1 state in Fig. 2 contain short (0–0.1 ms region) and long components (0.1 ms and onward). The short component corresponds to the relaxation process of the T1 state following intersystem crossing from the S1 state. The time of this process matches that of the rise in population density of Tb(III) ions. The longer component corresponds to the repopulation of the T1 state by BET from Tb(III) ions and as a result the decay rate is the same as for the Tb(III) ions. Population density of the longer component of the T1 state in the presence of TbET is lower than that in the absence of TbET, indicating suppression of BET. Table 1 summarizes the emission quantum yield Φππ*,calc and BET efficiency ηBET,calc obtained by the calculation for steady-state excitation. BET efficiency ηBET,calc is defined as the difference in yield of excited Tb(III) ions with BET (kBET = 3000 s−1) and without BET (kBET = 0 s−1). An approximately 3% decrease in BET efficiency ηBET,calc is observed in the Tb9 cluster in the presence of TbET compared to that in the absence of TbET. We also calculated the population density for a hypothetical cluster where all Tb(III) ions are in an identical environment to confirm the importance of Tb9 being isolated from BET (Supplementary Information S5 and Table S3). In this case, no change was observed in the emission lifetime, quantum yield, or BET efficiency regardless of the rate of TbET. These calculations clearly show that the combination of fast TbET and Tb9 plays a role in the suppression of BET in Tb9 cluster.

Calculated time evolution of population density of Tb9 cluster after short-pulse excitation of the ligands when TbET is present (kTbET = 50000 s−1, red) and when TbET is absent (kTbET = 0 s−1, blue).

The solid and dashed lines represent the collective population density of Tb(III) ions and T1 state, respectively.

Structure and Identification

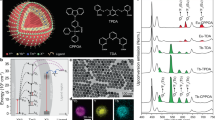

X-ray single-crystal analysis of Gd9 cluster was performed in order to understand the molecular structure and coordination geometry of the nine Ln(III) ions in TbnGd9−n clusters. The analysis showed that Gd(III) ions in the nonanuclear cluster take the form of an “hour-glass” structure in which the upper four and lower four Gd(III) ions are connected to the center Gd(III) ion via oxygen-bridging as shown in Fig. 3a. All Gd (III) ions take the form of an 8-coordination structure. The center Gd(III) ion is coordinated only by eight oxygen atoms. Each of the Gd(III) ions in the upper four and lower four sites (outer unit) are coordinated by both butylsalicylate ligands and oxygen atoms. The distances between two Gd(III) ions for all combinations are summarized in Table S4.

Evaluation of coordination geometry of Gd(III) ions was done through continuous shape measures (CShM) calculation using SHAPE55,56,57. The CShM criterion S, summarized in Table S5, represents the degree of deviation from ideal coordination geometry. We have chosen CShM over another method called “shape measure” (ShM)58 because it takes account of the distortion of center metal ion from the center of mass. The principle and comparison of the calculation method in CShM and ShM is described in Supplementary Information S7. The S value for the center Gd(III) ion (Fig. 3b) was 0.082 when calculated for 8-coordinated square antiprism (8-SAP) geometry and it was 2.481 for 8-coordinated trigonal dodecahedron (8-TDH) geometry. Therefore, the coordination geometry of the center Gd(III) ion is attributed to the 8-SAP structure. The upper four and lower four Gd(III) ionns (Fig. 3c) take an 8-TDH structure since the S values calculated for 8-TDH are smaller than those for 8-SAP. This structural result is similar to that of our previously reported Tb9 cluster50.

The structures of the other TbnGd9−n clusters (n = 1, 2, 5, 8) were determined by the combination of powder XRD (Figure S2a) and FAB-MS (Figure S2b). In the XRD results, the diffraction angle is corrected on the Si peak at 2θ = 28.43 degrees for accurate comparison of the peaks derived from the TbnGd9−n clusters. Three distinguished peaks (2θ1 = 11.3 degrees, 2θ2 = 15.6 degrees, and 2θ3 = 19.8 degrees) were observed for all of the clusters indicating that the mixed Tb/Gd clusters have the same structure as those of Tb9 and Gd9 clusters. This is further supported by FAB-MS spectroscopy which showed m/z value of the TbnGd9−n clusters corresponding to their calculated molecular weight without the NO3− counter-anion. The results presented above indicate that all TbnGd9−n clusters were successfully synthesized with identical structures.

Optical Properties

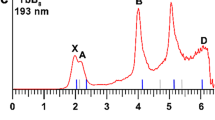

Emission spectra of TbnGd9−n clusters (n = 1, 2, 5, 8, 9) in 1.0 × 10−4 M chloroform solution were measured and Fig. 4a shows the spectra, normalized at the peak intensity. The TbnGd9−n clusters exhibit characteristic emission of the 4f-4f transition of the Tb(III) ion with each of the peaks corresponding to its 5D4 → 7FJ (J = 6 − 1) transitions59. The spectral shape of the emission was identical in all TbnGd9−n clusters. Additionally, the emission spectral shape of Tb9 cluster in powder form (Figure S4) was the same as that in the solution form, indicating that the coordination structure is maintained in solution. The emission spectrum of Gd9 cluster in 1.0 × 10−4 M chloroform solution at 210 K (Figure S5) was measured to estimate the excited triplet state (T1) energy level of the ligand38,60,61. The emission peak was observed at 461 nm (21690 cm−1). Since the 5D4 level of a Tb(III) ion is 20620 cm−1 as observed in the emission spectra (485 nm), the energy gap ΔE between T1 and 5D4 was estimated to be 1070 cm−1. This is well within the range for BET in Tb(III) complexes (ΔE < 1850 cm−1)33,34,38, and thus BET is expected to take place in TbnGd9−n clusters. The absolute emission quantum yield was determined by using an integration sphere (λEX = 380 nm, ligand excitation) and emission lifetimes were determined by using a nanosecond pulse laser (λEX = 355 nm, λEM = 550 nm, ligand excitation) for clusters in a chloroform solution. The emission decay profiles were single-exponential (Fig. 4b) in all TbnGd9−n clusters. As summarized in Table 2, the emission quantum yield Φππ* and lifetime τobs increased with increasing numbers of Tb(III) ions in the TbnGd9−n clusters. The emission quantum yield reflects the effect of all photophysical processes in TbnGd9−n clusters. Of these processes, TbET, PSET, and BET are all likely to vary with n in the TbnGd9−n clusters, and the effect purely based on TbET is indistinguishable.

(a) Photoluminescence spectra of TbnGd9−n clusters in 1.0 × 10−4 M chloroform solution normalized at the peak top. Excitation wavelength λEX was 380 nm. (b) Normalized emission lifetimes of TbnGd9−n clusters in 1.0 × 10−4 M chloroform solution at 300 K. All spectra were normalized at emission intensity at 0 seconds. All samples were excited by nanosecond pulse laser at λEX = 355 nm and monitored at λEM = 550 nm (5D4 → 7F6 transition).

The effect of TbET with increasing number of Tb(III) ions in the clusters was investigated by measuring the temperature dependence of emission lifetimes (Fig. 5). A clear temperature dependence was observed above 270 K for Tb1Gd8 and Tb2Gd7 clusters, while lifetimes remained constant for Tb5Gd4, Tb8Gd1, and Tb9 clusters. The rate constant of BET kBET can be estimated by the following equation37,62.

where τ is measured emission lifetime at a given temperature, τ210K is the emission lifetime at 210 K, A is frequency factor, EaBET is activation energy for BET, R is gas constant, and T is temperature. EaBET and kBET can be calculated for Tb1Gd8 cluster by an Arrhenius plot within the range in which temperature dependency was observed (Figure S6). The BET rate constant kBET and activation energy EaBET for Tb1Gd8 cluster were calculated to be 167 s−1 and 38.7 kJ mol−1, respectively (Table 2).

Emission lifetime and its temperature dependence are in qualitative agreement with theoretical results presented in the Theoretical Background section. The theoretical lifetime of Tb9 cluster in the absence of BET is constant regardless of TbET rate kTbET (Supplementary Information S4 and Table S2). Experimentally, BET is absent in TbnGd9−n clusters at 210 K, and the number of Tb(III) ions in the cluster is directly related to kTbET. Thus the emission lifetime at this temperature should be the same for all TbnGd9−n clusters. The experimental emission lifetimes of TbnGd9−n clusters at 210 K τ210K are approximately 1.12 ms regardless of the number of Tb(III) ions in the clusters (Table 2 and Fig. 5). Meanwhile, the theoretical lifetime of Tb9 clusters in the presence of BET shows that the lifetime is longer in the presence of TbET than in the absence of TbET. This comparison is analogous to experimental lifetimes of Tb9 cluster (presence of TbET) and Tb1Gd8 cluster (absence of TbET) at a temperature above 270 K, at which BET occurs. At a temperature above 270 K, the experimental lifetime is clearly longer for clusters with larger numbers of Tb(III) ions than for clusters with smaller numbers of Tb(III) ions. Such agreement between the theoretical and experimental results implies that the contribution of BET is indeed suppressed in Tb9 cluster because of TbET and the existence of a center Tb(III) ion not in direct contact with ligands for which no BET occurs.

Summary and Conclusion

The role of energy transfer between Tb(III) ions in luminescent Tb(III) complexes has been demonstrated to reduce BET losses both theoretically and experimentally using TbnGd9−n clusters ([TbnGd9−n(μ-OH)10(butylsalicylate)16]+NO3−) as model system. In the Theoretical Background section, we demonstrated that two features of Tb9 cluster were important for suppressing BET: 1) TbET by closely assembled Tb(III) ions and 2) existence of Tb9 that is isolated from BET. Experimentally, we synthesized and investigated the photophysical properties of nonanuclear TbnGd9−n clusters where n = 0, 1, 2, 5, 8, and 9. The combination of X-ray single-crystal analysis, powder XRD, and FAB-MS revealed that these clusters have nearly identical structures. Temperature dependency measurements of emission lifetime revealed that effect of BET becomes prominent in TbnGd9−n clusters at temperatures above 270 K. Below this temperature, the emission lifetime is constant for all clusters. Above 270 K, the decrease in emission lifetime is mitigated for clusters with over five Tb(III) ions. By comparing the trends observed in experimental results to those of theoretical results, it was found that the contribution of BET is indeed suppressed in clusters with a large number of Tb(III) ions. These findings provide a new insight into the fundamental photophysics of Ln(III) complexes as well as indication of a novel strategy to achieve higher luminescence efficiency in Ln(III) complexes.

Methods

Materials

Terbium(III) nitrate hexahydrate (Tb(NO3)3·6H2O) and triethylamine (C6H15N) were purchased from Kanto Chemical Co. Inc. Gadolinium(III) nitrate hexahydrate (Gd(NO3)3·6H2O) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. Butylsalicylate (C11H14O3) was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., LTD. All other chemicals and solvents were of reagent grade and were used without further purification.

Apparatus

FAB-MS spectra were measured on a JEOL JMS-700TZ. Elemental analyses were performed by Exter Analytical CE440. Infrared spectra were recorded on a JASCO FT/IR-4600 spectrometer. XRD spectra were characterized by a RIGAKU X-ray diffractometer RINT 2200. Single crystal X-ray diffractions were made on a RIGAKU RAXIS RAPID imaging plate area detector.

Optical Measurements

Absorption spectra of TbnGd9−n clusters were obtained by using a JASCO V-670 spectrometer. Emission spectra were measured using a Horiba/Jobin-Yvon FluoroLog-3 spectrofluorometer and a JASCO FP-6600 spectrometer. The combination of an integration sphere and a JASCO FP-6600 spectrometer was used to measure emission quantum yields. Emission lifetimes were measured using the third harmonic (355 nm) of a Q-switched Nd:YAG laser. The temperature was controlled using an Oxford Instruments OptistatDN2 cryostat.

Crystallography

Colorless single crystals of Gd9 cluster obtained from solutions in methanol were mounted on a glass fiber by using epoxy resin glue. All measurements were made using a Rigaku RAXIS RAPID imaging plate area detector with graphite-monochromated MoKα radiation. Corrections for decay and Lorentz-polarization effects were made using a spherical absorption correction, solved by direct methods, and expanded using Fourier techniques. Non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically except for disordered atoms. Hydrogen atoms were refined using the riding model. The final cycle of full-matrix least-squares refinement was based on observed reflections and variable parameters. All calculations were performed using a CrystalStructure crystallographic software package. We confirmed the CIF data by using the checkCIF/PLATON service. CCDC-1479981 (Gd9 cluster) contains the crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Synthesis of Gd9 cluster ([Gd9(μ-OH)10(butylsalicylate)16]+NO3−)

Butylsalicylate (1.05 g, 5.40 mmol) was dissolved in methanol, and triethylamine (1.22 ml, 8.80 mmol) was added to the solution and the solution was stirred at 40 °C. Then Gd(NO3)3·6H2O (1.372 g, 3.04 mmol) in methanol was added dropwise to the solution and the solution stirred for 30 minutes. The solution was cooled to room temperature, and white powder Gd9 cluster ([Gd9(μ-OH)10(butylsalicylate)16]+NO3−) was obtained 15 minutes later. Yield: 59%. Selected IR (ATR, cm−1): 3573 (w, O–H), 3234 (w, O–H), 2956 (m, C–H), 1318 (s, C–O). FAB-MS: m/z = 4676.8 [Gd9(μ-OH)10(butylsalicylate)16]+. Elemental analysis calculated for C176H218NO61Gd9: C, 44.61%, H, 4.64%, N, 0.30%. Found: C, 44.30%, H, 4.53%, N, 0.25%.

Synthesis of Tb1Gd8 cluster ([Tb1Gd8(μ-OH)10(butylsalicylate)16]+NO3−)

Tb1Gd8 cluster was synthesized by the same procedure as that used for Gd9 cluster except for the use of Tb(NO3)3·6H2O (0.172 g, 0.380 mmol) and Gd(NO3)3·6H2O (1.24 g, 2.73 mmol). Yield: 82%. Selected IR (ATR, cm−1): 3573 (w, O–H), 3234 (w, O–H), 2956 (m, C–H), 1318 (s, C–O). FAB-MS: m/z = 4677.8 [Tb1Gd8(μ-OH)10(butylsalicylate)16]+. Elemental analysis calculated for C176H218NO61Tb1Gd8: C, 44.59%, H, 4.64%, N, 0.30%. Found: C, 43.95%, H, 4.53%, N, 0.29%.

Synthesis of Tb2Gd7 cluster ([Tb2Gd7(μ-OH)10(butylsalicylate)16]+NO3−)

Tb2Gd7 cluster was synthesized by the same procedure as that used for Gd9 cluster except for the use of Tb(NO3)3·6H2O (0.306 g, 0.675 mmol) and Gd(NO3)3·6H2O (1.07 g, 2.36 mmol). Yield: 51%. Selected IR (ATR, cm−1): 3573 (w, O–H), 3234 (w, O–H), 2956 (m, C–H), 1318 (s, C–O). FAB-MS: m/z = 4679.8 [Tb2Gd7(μ-OH)10(butylsalicylate)16]+. Elemental analysis calculated for C176H218NO61Tb2Gd7: C, 44.58%, H, 4.63%, N, 0.30%. Found: C, 44.32%, H, 4.54%, N, 0.26%.

Synthesis of Tb5Gd4 cluster ([Tb5Gd4(μ-OH)10(butylsalicylate)16]+NO3−)

Tb5Gd4 cluster was synthesized by the same procedure as that used for Gd9 cluster except for the use of Tb(NO3)3·6H2O (0.688 g, 1.52 mmol) and Gd(NO3)3·6H2O (0.684 g, 1.52 mmol). Yield: 41%. Selected IR (ATR, cm−1): 3573 (w, O–H), 3234 (w, O–H), 2956 (m, C–H), 1318 (s, C–O). FAB-MS: m/z = 4684.9 [Tb5Gd4(μ-OH)10(butylsalicylate)16]+. Elemental analysis calculated for C176H218NO61Tb5Gd4: C, 44.53%, H, 4.63%, N, 0.30%. Found: C, 44.23%, H, 4.52%, N, 0.24%.

Synthesis of Tb8Gd1 cluster ([Tb8Gd1(μ-OH)10(butylsalicylate)16]+NO3−)

Tb8Gd1 cluster was synthesized by the same procedure as that used for Gd9 cluster except for the use of Tb(NO3)3·6H2O (1.026 g, 2.26 mmol) and Gd(NO3)3·6H2O (0.344 g, 0.762 mmol). Yield: 49%. Selected IR (ATR, cm−1): 3573 (w, O–H), 3234 (w, O–H), 2956 (m, C–H), 1318 (s, C–O). FAB-MS: m/z = 4689.8 [Tb8Gd1(μ-OH)10(butylsalicylate)16]+. Elemental analysis calculated for C176H218NO61Tb8Gd1: C, 44.48%, H, 4.62%, N, 0.29%. Found: C, 44.24%, H, 4.53%, N, 0.24%.

Synthesis of Tb9 cluster ([Tb9(μ-OH)10(butylsalicylate)16]+NO3−)

Tb9 cluster was synthesized by the same procedure as that used for Gd9 cluster except for the use of Tb(NO3)3·6H2O (1.372 g, 3.04 mmol). Yield: 52%. Selected IR (ATR, cm−1): 3573 (w, O–H), 3234 (w, O–H), 2956 (m, C–H), 1318 (s, C–O). FAB-MS: m/z = 4691.3 [Tb9(μ-OH)10(butylsalicylate)16]+. Elemental analysis calculated for C176H218NO61Tb9: C, 44.47%, H, 4.62%, N, 0.29%. Found: C, 44.20%, H, 4.57%, N, 0.27%.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Omagari, S. et al. Critical Role of Energy Transfer Between Terbium Ions for Suppression of Back Energy Transfer in Nonanuclear Terbium Clusters. Sci. Rep. 6, 37008; doi: 10.1038/srep37008 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Kikuchi, K. Design, synthesis and biological application of chemical probes for bio-imaging. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 2048–2053 (2010).

Ueno, Y. et al. Molecular design for enhanced sensitivity of a FRET aptasensor built on the graphene oxide surface. Chem. Commun. 49, 10346–10348 (2013).

Aoki, K. & Matsuda, M. Visualization of small GTPase activity with fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based biosensors. Nat. Protoc. 4, 1623–1631 (2009).

Singh-Rachford, T. N. & Castellano, F. N. Photon upconversion based on sensitized triplet-triplet annihilation. Coord. Chem. Rev. 254, 2560–2573 (2010).

Ji, S., Guo, H., Wu, W., Wu, W. & Zhao, J. Ruthenium(II) polyimine-coumarin dyad with non-emissive 3IL excited state as sensitizer for triplet-triplet annihilation based upconversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 8283–8286 (2011).

Mahato, P., Monguzzi, A., Yanai, N., Yamada, T. & Kimizuka, N. Fast and long-range triplet exciton diffusion in metal-organic frameworks for photon upconversion at ultralow excitation power. Nat. Mater. 14, 924–930 (2015).

D’Andrade, B. W. et al. High-efficiency yellow double-doped organic light-emitting devices based on phosphor-sensitized fluorescence. Appl. Phys. Lett. 79, 1045–1047 (2001).

Montes, V. A., Pérez-Bolívar, C., Agarwal, N., Shinar, J. & Anzenbacher, P. Molecular-wire behavior of OLED materials: exciton dynamics in multichromophoric Alq3-oligofluorene-Pt(II) porphyrin triads. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 12436–12438 (2006).

Wang, S. et al. Achieving high power efficiency and low roll-off OLEDs based on energy transfer from thermally activated delayed excitons to fluorescent dopants. Chem. Commun. 51, 11972–11975 (2015).

Dexter, D. L. A theory of sensitized luminescence in solids. J. Chem. Phys. 21, 836–850 (1953).

Förster, T. 10th Spiers memorial lecture - transfer mechanisms of electronic excitation. Discuss. Faraday Soc. 7–17 (1959).

Berezin, Y. M. & Achilefu, S. Fluorescence lifetime measurements and biological imaging. Chem. Rev. 110, 2641–2684 (2010).

Duysens, L. N. M. Transfer of light energy within the pigment systems present in photosynthesizing cells. Nature 168, 548–550 (1951).

Irish, E. K., Gómez-Bombarelli, R. & Lovett, B. W. Vibration-assisted resonance in photosynthetic excitation-energy transfer. Phys. Rev. A 90, 012510-1–012510-10 (2014).

Brixner, T. et al. Two-dimensional spectroscopy of electronic couplings in photosynthesis. Nature 434, 625–628 (2005).

Hardin, B. E., Snaith, H. J. & Mcgehee, M. D. The renaissance of dye-sensitized solar cells. Nature Photon. 6, 162–169 (2012).

Siegers, C. et al. Overcoming kinetic limitations of electron injection in the dye solar cell via coadsorption and FRET. ChemPhysChem 9, 793–798 (2008).

Eliseeva, S. V. & Bünzli, J.-C. G. Lanthanide luminescence for functional materials and bio-sciences. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 189–227 (2010).

Hasegawa, Y., Wada, Y. & Yanagida, S. Strategies for the design of luminescent lanthanide(III) complexes and their photonic applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 5, 183–202 (2004).

Judd, B. R. Optical absorption intensities of rare-earth ions. Phys. Rev. 127, 750–761 (1962).

Ofelt, G. S. Intensities of crystal spectra of rare-earth ions. J. Chem. Phys. 37, 511–520 (1962).

Bünzli, J.-C. G. & Eliseeva, S. V. Intriguing aspects of lanthanide luminescence. Chem. Sci. 4, 1939–1949 (2013).

Parker, D., Dickins, R. S., Puschmann, H., Crossland, C. & Howard, J. A. K. Being excited by lanthanide coordination complexes: Aqua species, chirality, excited-state chemistry, and exchange dynamics. Chem. Rev. 102, 1977–2010 (2002).

Moore, E. G., Samuel, A. P. S. & Raymond, K. N. From antenna to assay: lessons learned in lanthanide luminescence. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 542–552 (2009).

Jin, T., Inoue, S., Machida, K. & Adachi, G. Photovoltaic cell characteristics of hybrid silicon devices with lanthanide complex phosphor-coating film. J. Electrochem. Soc. 144, 4054–4058 (1997).

Bünzli, J.-C. G. & Piguet, C. Taking advantage of luminescent lanthanide ions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 34, 1048–1077 (2005).

de Bettencourt-Dias, A. Lanthanide-based emitting materials in light-emitting diodes. Dalton Trans. 2229–2241 (2007).

Kido, J. & Okamoto, Y. Organo lanthanide metal complexes for electroluminescent materials. Chem. Rev. 102, 2357–2368 (2002).

Ahmed, Z. & Iftikhar, K. Efficient photoluminescent complexes of 400–1800 nm wavelength emitting lanthanides containing organic sensitizers for optoelectronic devices. RSC Adv. 4, 63696–63711 (2014).

Marchionna, S. et al. Photovoltaic quantum efficiency enhancement by light harvesting of organo-lanthanide complexes. J. Lumin. 118, 325–329 (2006).

Rocha, J., Carlos, L. D., Almeida Paz, F. A. & Ananias, D. Luminescent multifunctional lanthanides-based metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 926–940 (2011).

de Sá, G. F. et al. Spectroscopic properties and design of highly luminescent lanthanide coordination complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 196, 165–195 (2000).

Smentek, L. & Kdziorski, A. Efficiency of the energy transfer in lanthanide-organic chelates; spectral overlap integral. J. Lumin. 130, 1154–1159 (2010).

Latva, M. et al. Correlation between the lowest triplet state energy level of the ligand and lanthanide(III) luminescence quantum yield. J. Lumin. 75, 149–169 (1997).

Katagiri, S., Tsukahara, Y., Hasegawa, Y. & Wada, Y. Energy-transfer mechanism in photoluminescent terbium(III) complexes causing their temperature-dependence. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 80, 1492–1503 (2007).

Karbowiak, M., Cichos, J. & Buczko, K. Interaction of lanthanide β-diketonate complexes with polyvinylpyrrolidone: proton-controlled switching of Tb3+ luminescence. J. Phys. Chem. B 118, 226–239 (2014).

Omagari, S. et al. Effective photosensitized energy transfer of nonanuclear terbium cluster using methyl salicylate derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. A 119, 1943–1947 (2015).

Gutierrez, F. et al. Quantum chemistry-based interpretations on the lowest triplet state of luminescent lanthanides complexes. Part 1. relation between the triplet state energy of hydroxamate complexes and their luminescence properties. Dalton Trans. 1334–1347 (2004).

Nasso, I. et al. Highly luminescent Tb(III) macrocyclic complex based on a DO3A hosting unit and an appended carboxylated N,C-pyrazolylpyridine antenna. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 274, 124–132 (2014).

de Bettencourt-Dias, A., Barber, P. S. & Bauer, S. A water-soluble pybox derivative and its highly luminescent lanthanide ion complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 6987–6994 (2012).

Zaïm, A. et al. Lanthanide-to-lanthanide energy-transfer processes operating in discrete polynuclear complexes: can trivalent europium be used as a local structural probe? Chem. Eur. J. 20, 12172–12182 (2014).

Lemonnier, J.-F. et al. Optimizing sensitization processes in dinuclear luminescent anthanide oligomers: selection of rigid aromatic spacers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 16219–16234 (2011).

Alexandropoulos, D. I. et al. Tetranuclear lanthanide(III) complexes with a zigzag topology from the use of pyridine-2,6-dimethanol: synthetic, structural, spectroscopic, magnetic and photoluminescence studies. Inorg. Chem. 53, 3220–3229 (2014).

Wang, R., Song, D. & Wang, S. Toward constructing nanoscale hydroxo-lanthanide clusters: syntheses and characterizations of novel tetradecanuclear hydroxo-lanthanide clusters. Chem. Commun. 368–369 (2002).

Mazarakioti, E. C., Poole, K. M., Cunha-Silva, L., Christou, G. & Stamatatos, T. C. A new family of Ln7 clusters with an ideal D3h metal-centered trigonal prismatic geometry, and SMM and photoluminescence behaviors. Dalton Trans. 43, 11456–11460 (2014).

Artizzu, F. et al. Ln3Q9 as a molecular framework for ion-size-driven assembly of heterolanthanide (Nd, Er, Yb) multiple near-infrared emitters. Chem. Eur. J. 21, 3882–3885 (2015).

Huang, C. Rare earth coordination chemistry: fundamentals and applications. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Singapore (2010).

Woodruff, D. N., Winpenny, R. E. P. & Layfield, R. A. Lanthanide single-molecule magnets. Chem. Rev. 113, 5110–5148 (2013).

Andrews, P. C., Gee, W. J., Junk, P. C. & Massi, M. Variation of structural motifs in lanthanoid hydroxo clusters by ligand modification. New J. Chem. 37, 35–48 (2013).

Nakanishi, T. et al. Enhancement of optical faraday effect of nonanuclear Tb(III) complexes. Inorg. Chem. 53, 7635–7641 (2014).

Wada, S. et al. The relationship between magneto-optical properties and molecular chirality. 8, e251 (2016).

Malta, O. L. Mechanisms of non-radiative energy transfer involving lanthanide ions revisited. J. Non. Cryst. Solids 354, 4770–4776 (2008).

Tobita, S., Arakawa, M. & Tanaka, I. The paramagnetic metal effect on the ligand localized S1-T1 intersystem crossing in the rare-earth-metal complexes with methyl salicylate. J. Phys. Chem. 89, 5649–5654 (1985).

Yang, Y. et al. Listening to lanthanide complexes: determination of the intrinsic luminescence quantum yield by nonradiative relaxation. ChemPhysChem 9, 600–606 (2008).

Casanova, D., Llunell, M., Alemany, P. & Alvarez, S. The rich stereochemistry of eight-vertex polyhedra: a continuous shape measures study. Chem. Eur. J. 11, 1479–1494 (2005).

SHAPE, version 2.1. Continuous shape measures calculations. Electronic Structure Group, Universitat de Barcelona: Spain (2010).

Pinsky, M. & Avnir, D. Continuous symmetry measures. 5. the classical polyhedra. Inorg. Chem. 37, 5575–5582 (1998).

Xu, J., Radkov, E., Ziegler, M. & Raymond, K. N. Plutonium(IV) sequestration: structural and thermodynamic evaluation of the extraordinarily stable cerium(IV) hydroxypyridinonate complexes. Inorg. Chem. 39, 4156–4164 (2000).

Beitz, J. V. f-State luminescence of trivalent lanthanide and actinide ions in solution. J. Alloys Compd. 207/208, 41–50 (1994).

Bassett, A. P. et al. Highly luminescent, triple- and quadruple-stranded, dinuclear Eu, Nd, and Sm(III) lanthanide complexes based on bis-diketonate ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 9413–9424 (2004).

Terai, T. et al. Modulation of luminescence intensity of lanthanide complexes by photoinduced electron transfer and its application to a long-lived protease probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 6938–6946 (2006).

Miyata, K. et al. Chameleon luminophore for sensing temperatures: control of metal-to-metal and energy back transfer in lanthanide coordination polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 6413–6416 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas of “New Polymeric Materials Based on Element-Blocks (No. 2401)” (24102012) of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan and by the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B), 15K18206, 2015. We are also grateful for the support of Frontier Chemistry Center Akira Suzuki “Laboratories for Future Creation” Project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.O. performed all the syntheses and measurements, and wrote the paper under the supervision of T.N. and Y.H. S.O., T.N., Y.K., K.F., A.M., and Y.H. discussed and designed the research. T.S. and H.I. supported the single crystal and power XRD measurements. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Omagari, S., Nakanishi, T., Kitagawa, Y. et al. Critical Role of Energy Transfer Between Terbium Ions for Suppression of Back Energy Transfer in Nonanuclear Terbium Clusters. Sci Rep 6, 37008 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37008

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37008

This article is cited by

-

A luminescent view of the clickable assembly of LnF3 nanoclusters

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Octanuclear {Ln8} complexes: magneto-caloric effect in the {Gd8} analogue

Journal of Chemical Sciences (2021)

-

Enhanced Optoelectronic and Biological Potential of Virescent-Glowing Terbium(III) Complexes with Pyrazole Acid

Journal of Electronic Materials (2021)

-

Effective photosensitized, electrosensitized, and mechanosensitized luminescence of lanthanide complexes

NPG Asia Materials (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.