Abstract

Accurate estimation of relative carbon deposition (marine vs. terrestrial) is required for understanding the global carbon budget, particularly in the Arctic region, which holds disproportionate importance with respect to global carbon cycling. Although the sedimentary organic matter (SOM) concentration and its isotopic composition are important tools for such calculations, uncertainties loom over estimates provided by organic-geochemical bulk parameters. We report carbon and nitrogen concentrations and isotopes (δ13C and δ15N) of SOM at an Arctic fjord namely Kongsfjorden. We find that the bound inorganic nitrogen (ammonium attached to the clay minerals) forms a significant proportion of total nitrogen concentration (~77% in the inner fjord to ~24% in the outer part). On removing the bound nitrogen, the C/N ratio shows that the SOM in the inner fjord is made up of terrestrial carbon while the outer fjord shows mixed marine-terrestrial signal. We further show that the marine organic matter is unusually more depleted in 13C (~−24‰) than the terrestrial organic matter (~−22.5‰). This particular finding also helps explain high δ13C values of SOM as noted by earlier studies in central Arctic sediments despite a high terrestrial contribution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although atmospheric carbon represents only a small part of the total carbon present on earth1,2, it’s ever increasing rate over the last few centuries is widely recognized as an existential threat to life on this planet. The atmosphere is essentially a large flux reservoir for carbon whose concentration depends on the exchanges with other reservoirs3. One such exchange is the burial of land and marine synthesized organic carbon as sedimentary organic matter (SOM) into the ocean and forms an important part of the global carbon cycle. Apart from serving as a tool for studying depositional environment, transport pathways, remineralization, and past climate conditions, source characterization of SOM is required to estimate the burial rates of marine and terrigenous organic matter4,5,6,7,8. Although various geochemical proxies such as the C/N ratio of SOM6,9, specific biomarkers10 and Rock-Eval parameters11 are used to identify relative composition of land and marine derived components of SOM, it’s carbon isotopic composition is one of the most widely used tracer12,13,14,15. However, gross differences exist between different estimates16 primarily on account of proxy specific limitations. δ13C based provenance determination is limited in its applicability due to uncertainty associated with land and marine end-member isotopic compositions. This problem is of particular interest in the Arctic region, given it’s uniqueness as compared to other world oceans and its disproportionate importance in the global carbon budget17 and global climate system at large.

Terrestrial carbon is an important source of organic carbon preserved in marine sediments. The fraction making its way into the ocean, having survived a great deal of oxidizing pressure during transport, is highly refractory and thus constitute a high proportion in buried sediments not only in the near shore environments but also in the open ocean sediments. It is also the one which may be subject to significant change on account of land-use changes due to anthropogenic activities18,19. Marine organic carbon, on the other hand, is highly labile and suffers significant degradation during its vertical transport. Less than 1% of marine carbon produced in sub-surface waters gets buried with sediments depending upon the type of depositional environment20. Although riverine and eolian flux (0.43–0.75 Gt/y) into the oceans is very small compared to the primary productivity (30–50 Gt/y), up to 0.1 Gt/y of the total 0.16 Gt/y of estimated burial flux may be from the terrestrial source alone17. The Arctic ocean plays an important role in the global carbon cycle by accounting for 7–11% of the global burial flux, although it represents only 2.5% of the world ocean area17. This is primarily due to high terrestrial deposition in central and marginal environments of Arctic Ocean where transportation is facilitated via sea ice16.

Assumptions regarding the isotopic composition of terrestrial and marine end members limit the applicability of bulk isotopic composition of SOM for source characterization (provenance). This is especially important in the Arctic region where uncertainty exists for marine end-member isotopic composition on account of high pCO2 in cold surface water. The δ13C values between −26‰ to −28‰ is often taken as the terrestrial end member for C-3 plants upon an estimated 20‰ fractionation from the atmospheric CO2 value of −7‰5,6,21,22. C-4 plants play a minor role in high-latitude regions like the Arctic Ocean23. In mid to low latitude regions, δ13C value of −20‰ to −22‰ is commonly assigned to marine organic matter5. However, a range of values between −16.7‰ to −30.4‰ has been suggested for high latitudes, making it difficult to have reliable assumptions regarding δ13C of marine organic carbon in the Arctic region24,25. Yet another problem with respect to organic matter source characterization in the Arctic sediments is the impact of land derived bound nitrogen on the C/N ratio of bulk sediments8. The presence of high clay content in Arctic sediments leads to high proportion of bound inorganic nitrogen9. If the inorganic component is not actively removed, the C/N ratio based source characterization may be significantly underestimated with respect to the terrestrial organic matter.

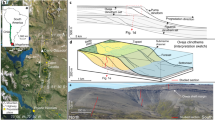

One of the ways to address the problem of constraining isotopic end-member composition is to investigate the spatial variability of geochemical properties of SOM along a steep productivity gradient with adequate terrestrial contribution. Productivity gradient leads to variation in the mixing ratio between the marine and the terrestrial carbon along the gradient. Isotopic measurements along the gradient would thus help in constraining the end-member isotopic compositions. In this study, we have investigated the spatial variability of SOM and its carbon and nitrogen isotopic composition using surface sediments at a site with steep marine productivity gradient and ample terrestrial input. The study region is Kongsfjorden (Fig. 1), a fjord system in the Arctic region, located in the western part of Spitsbergen Island, the largest among the Svalbard archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. It is known for its strong hydrological, sedimentological and biological gradients along the axis26. Previous records from the region27,28 are limited and a knowledge gap exists. Results from the spatial variability of SOM in surface sediments will also form the groundwork for high-resolution long core studies from the region.

Map of Kongsfjorden and Spitsbergen (modified after Shetye et al. 27, with permission from John Wiley and Sons Inc.).

Sampling locations are shown in red. Surface samples were collected along the fjord axis (I-1 to I-8) and across the fjord axis (I-2A to I-2C). Map modified using Adobe Photoshop CS5 ( www.adobe.com/in/products/photoshop).

Study Area

Kongsfjorden is situated between 78°40′ and 77°30′N and 11°3′ and 13°6′E. Approximately 20 km long, its width varies between 4 km and 10 km. The inner fjord is marked by relatively shallow depth (less than 100 m) as compared to the outer fjord (~250 m). Around 80% of the catchment area is glaciated, with two active glaciers towards the head and three towards the northern coast. The southern coast is relatively ice free with no active glacier. Western Spitsbergen is flanked by a northerly warm West Spitsbergen current (WSC), with Atlantic water mass (AW) constituting the top 600 m. A cold coastal current with Arctic water (ArW) also traverses the shelf in the outer fjord region. The presence of these currents towards the mouth of the fjord give rise to fronts and instabilities associated with them causes exchange of warm saline shelf transformed Atlantic water with the cold freshwater from the glacial discharge. Mass balance studies from Kongsfjorden have shown that the major contribution of fresh water into the fjord comes from the glacial discharge29 since precipitation plays a limited role. Climate change can affect both cross-shelf exchange of water mass between Atlantic, Arctic and freshwater as well as glacial discharge into the fjord. The temperature of AW in the WSC has increased in the recent years owing to coupled ocean-atmosphere interaction associated with the positive phase of North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO)30.

Results and Discussion

Total organic carbon and total nitrogen concentration

The organic carbon content in the surface sediments shows an increasing trend from approximately 0.5% at the fjord head to nearly 2% at the mouth. The total nitrogen concentration in surface sediments follows a similar trend with a minimum of 0.03% at the fjord head and a maximum of 0.21% in the outer part (Fig. 2a). Across the fjord axis, at I-2, TOC increases from nearly 1% at the glaciated northern coast to 2.1% close to southern coast. TN increases from 0.08% to nearly 0.2% along the same stretch (Fig. 3a). TOC/TN ratio in surface sediments (Fig. 2b) varies between 8 and 16. Spatial variability of TOC/TN in surface sediments shows a declining trend between the fjord head and the fjord mouth with the exception of station I-4 with abnormally high value. Across the fjord axis (Fig. 3c), it decreases between the northern and the southern coast at I-2.

(a) Spatial variability of TOC, TN and TOC/TN of surface sediments along the fjord axis. Systematic increase in TOC and TN and decline in TOC/TN ratio is observed from inner fjord to outer fjord. (b) δ13C and δ15N of surface sediments. The inner fjord sediments are depleted in 15N and enriched in 13C compared to the outer part. (c) Relative proportion of bound-inorganic nitrogen concentration and organic nitrogen concentration in surface sediments. Inorganic nitrogen constitutes a significant proportion of total nitrogen concentration. The organic fraction increases systematically away from the fjord head. (d) TOC//Norganic, δ15N bound & δ15Norganic of surface sediments. High TOC/Norganic in the inner fjord is suggestive of predominantly terrestrial organic matter deposition in surface sediments in the inner part of the fjord. A more mixed marine-terrestrial signature is seen in the outer fjord region.

TOC and TN in surface sediments at Kongsfjorden show a clear spatial gradient with lower values in the glacier dominated inner fjord and higher values towards the outer fjord. This trend is also preserved between the glaciated northern coast and glacier free southern coast, suggesting role of a common factor. Although high turbidity towards the fjord head, which give rise to a shallow photic zone, is often cited as the reason for such a trend in TOC and TN profile27, steep gradient in sedimentation rate and grain size sorting may have a role in producing such a profile. A high correlation between TOC and TN exist in the surface sediments (r2 = 0.88). The C/N ratio in marine organisms, given by Redfield31 and later modified32 ranges between 6.5 and 8.7 (C:N:P = 122 (±18):16:1). Terrestrial organic matter predominantly consists of compounds like cellulose, lignin etc. with a low nitrogen content. Therefore the C/N value in land derived organic matter is much higher and found to vary between 20 and 1007. TOC/TN in sediments from Kongsfjorden suggest mixed terrestrial-marine source with increasing marine influence towards the fjord mouth. Its decline across the fjord axis between the northern and the southern coast may be attributed to high terrestrial input at the northern coast. Abnormally high value at I-4 is probably due to shallow water depth and high current regime associated with low bathymetry. This is also evident from low microfossil abundance at I-4 dominated by Cibicides Lobatulus which is known for its association with high current conditions33 (manuscript under preparation). The effect of removing bound nitrogen on C/N ratio is discussed in a separate section.

δ13C of sedimentary organic matter

Sedimentary organic matter in the inner fjord region is found to be more enriched in 13C compared to the outer fjord. The δ13C in surface sediments varies from nearly −22.5‰ in the inner fjord to about −24‰ in the outer fjord (Fig. 2b). The complete data is given in Table S1 in the Supplementary Information. Across the fjord axis, it varies from −24.35‰ at the southern coast to −22.87‰ at the northern coast close to station I-3 (Fig. 3b). Overall, the δ13C values in sediments are very close to that from other records from Svalbard region, but lower than those reported from the central Arctic region9.

Variation of δ13C in sediments primarily reflects varying mixing ratio of terrestrial and marine organic carbon, with their distinct isotopic signatures. C-3 plants are the most common terrestrial source of organic matter in sediments with δ13C values ranging from −22‰ to −30‰ (average −27‰)34,35. δ13C of marine organic matter on the other hand is found to vary between −10‰ to −31‰, with most of them constrained between −17‰ and −22‰36. Low temperature regions with high pCO2 in surface waters leads to high fractionation during photosynthesis by plankton, resulting in more depleted carbon isotopic composition37. Trend shown by δ13C in surface sediments suggest terrestrial organic matter in Kongsfjorden is more enriched compared to that of the marine as the inner fjord region with predominantly terrestrial organic carbon (discussed under section “Role of soil derived bound inorganic nitrogen concentration in surface sediments”) has higher δ13C. Outer fjord region with increasing marine influence records lower δ13C. Similar explanation holds for δ13C trend across the fjord axis between the southern and the northern coast. Low δ13C of marine organic matter is also evident through a positive correlation between δ13C and the C/N ratio in surface sediments (Fig. 4). This result also seems to explain why the central Arctic region with high terrestrial input38,39 has more enriched carbon isotopic composition of SOM. An important implication of this finding is that fixed isotopic composition of end-members (lower ~−27‰ for terrestrial and higher ~−22‰ for marine) is often used for organic matter source characterization9, which in this case would result in an incorrect reconstruction. The difference between the estimates using above fixed end-member values and that inferred through the present study is shown in Fig. 5, for which the calculation is explained in the section “Role of soil derived bound inorganic nitrogen concentration in surface sediments”. δ13C vs. C/N plot shows mixed marine-terrestrial source for organic matter in surface sediment from Kongsfjorden (Supplementary Fig. S1). The effect of removing bound nitrogen on this plot is discussed under the section “Role of soil derived bound inorganic nitrogen concentration in surface sediments”.

δ15N of sedimentary organic matter

δ15N in surface sediments shows an increasing trend between the inner fjord and the outer fjord. From around 3.7‰ at the head, it reaches to greater than 5‰ at the mouth. Across the fjord axis, 1.2‰ shift in δ15N can be seen at I-2 (Figs 2b and 3d). Overall δ15N in surface sediments are lower compared to central Arctic record9. δ15N trend in surface sediments, both along and across the fjord axis suggest high nutrient utilization in the glacier distal region (outer fjord) as compared to the inner region. Higher δ15N in outer fjord region indicates a low surface nitrate concentration. Nutrient laden Atlantic water influx in the outer fjord region may have offset some of the increase in δ15N with increasing marine productivity and may also explains the reason behind lighter nitrogen isotopic composition of SOM at Kongsfjorden as compared to the central Arctic record which has less Atlantic water influence. The correlation between δ15N and δ13C and that between δ15N and C/N ratio are both negative (Fig. 4). The negative correlation in our case is because a high δ15N is suggestive of a higher marine productivity while we have shown that both δ13C and the C/N ratio of marine productivity are low.

Role of soil derived bound inorganic nitrogen concentration in surface sediments

High clay content in arctic sediments39,40 leads to significant amount of inorganic nitrogen bound to them41,42 as seen from the nitrogen content in KOBr-KOH treated surface sediments. The inorganic nitrogen bound as ammonium in clay minerals varies from about 0.03% in the inner fjord to nearly 0.06% in the outer fjord region in surface sediments, showing an increasing trend along the fjord axis (Fig. 2c). The organic nitrogen concentration (Ntotal − Nbound) increases from 0.01% in the inner fjord to about 0.15% in the outer region. The organic fraction constitute between 24% to 76% of total nitrogen concentration, increasing sharply between the inner fjord and the outer fjord (Fig. 2c). The correlation coefficient between organic carbon and organic nitrogen improves slightly (r2 = 0.90) from that between TOC and total nitrogen in surface sediments (Fig. 6). Corganic/Norganic ratio shows a more pronounced gradient between the inner fjord and the outer fjord as compared to that shown by Corganic/Ntotal along the fjord axis. In the inner fjord it is greater that 60 indicating predominantly terrestrial source of SOM while dropping to around 20 in the central fjord and further down to 12 in the outer fjord suggesting increasing marine influence along the fjord axis (Fig. 2d). The δ15Norganic, estimated assuming mass balance between organic and inorganic fractions, varies from 4.05‰ in the inner fjord to 6.47‰ in the outer fjord, significantly higher than δ15Ntotal at each location. These are lighter compared to organic nitrogen isotopic composition from central Arctic region9. δ15Nbound on the other hand exhibit a much narrower range (2.7‰ to 3.6‰) as compared to δ15Norganic with a mean of 3.28‰ (Fig. 2d).

Our record shows bound nitrogen constitute about 75% of total nitrogen in the inner fjord region and account for 25–30% in the outer fjord region. High clay content in Arctic sediments leads to significantly high amount of inorganic nitrogen attached to potassium rich minerals, coming from terrestrial runoff. A marked increase in bound nitrogen concentration from inner fjord to the mouth may have been from increasing clay content towards the open ocean. Interestingly, despite this increase in inorganic nitrogen along the fjord axis, the organic nitrogen fraction increases from as low as 23% to about 75% along the same stretch, indicating increasing marine influence in the glacier distal region. Overall organic nitrogen fraction as well as the total organic nitrogen content is higher than that reported from the central Arctic region9. The distinction between bound and organic nitrogen becomes more evident by comparing C/N ratio calculated from total nitrogen and organic nitrogen. The former significantly underestimates the terrestrial contribution to SOM; especially in the glacier proximal region with overwhelming terrestrial contribution (C/Norganic > 60) misrepresented as mixed marine-terrestrial (C/Ntotal ~15). This further lead us to attribute the δ13C signature coming out of the SOM from the inner most part of the fjord to be predominantly of terrestrial source, as can also be seen in the δ13C vs. C/N plot (Supplementary Fig. S1). This allows us to constrain the terrestrial end-member carbon isotopic composition at our site, which is unusually found to be more than the marine-endmember. Based on the TOC/Norganic values (assuming innermost value to be purely of terrestrial origin and a marine end-member value of 6) we estimated the δ13C of marine organic matter as −24.2‰. First we calculated the terrestrial fraction of SOM at station I-1 (eq. 1 below) using which δ13Cmarine was calculated (eq. 2 below).

here, fterrestrial represents terrestrial component of total SOM whereas subscripts represent respective station number (I-1, and I-8). Using this derived marine end-member δ13C value and the inferred terrestrial end-member δ13C value, terrestrial contribution to the SOM is obtained as per the equation shown below (eq. 3).

The difference between the terrestrial carbon concentrations based on fixed end-member δ13C values and those obtained using estimated end-member δ13C value is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 6 shows that using Norganic improves the correlation between carbon and nitrogen and lowers the intercept of the linear regression curve between the two. A comparatively larger intercept shown by regression curve between TOC and TN indicates the presence of bound nitrogen. Narrow range exhibited by the isotopic composition of bound nitrogen suggests well-defined δ15N for inorganic nitrogen, possibly representing signal from land. Moreover lower values closer to atmospheric nitrogen (δ15N = 0‰) may have been from minor fractionation by land plants43. δ15Norganic shows a more pronounced spatial variability as compared to δ15Ntotal indicating better nutrient utilization in the outer fjord region. Lighter nitrogen isotopic composition compared to central Arctic record suggests the role of Atlantic water influx into the region.

Summary

Multi-proxy record from surface sediments at Kongsfjorden shows a clear spatial gradient in bulk geochemical parameters, largely driven by the glacial-marine contrast. A similar gradient exists across the fjord axis between the glaciated northern coast and glacier free southern coast. Organic matter concentration increases with increasing distance from the glaciers. C/N ratio suggests SOM in the inner fjord region is dominated by terrestrial source while marine signature becomes dominant away from the glaciers. High clay content in sediments from Arctic region requires that bound nitrogen should be actively removed to interpret C/N and δ15N results. δ13C trend suggests marine organic matter to be more depleted in 13C compared to its terrestrial counterpart. This particular finding helps explain higher δ13C values in central Arctic sediments compared to Svalbard. It also has important implications for constraining end-member isotopic composition for δ13C based source characterization of sedimentary organic matter in Arctic region. δ15N shows better nutrient utilization away from the glacier and the influence of Atlantic water mass in western Spitsbergen.

Methods

Eleven surface sediment grabs were collected at various water depths during August 2014 from Kongsfjorden (Table 1). Surface sediments were collected using Grab Sampler using the workboat “MS Teisten”. Samples are named according to their station number at each location. The samples were brought back to the laboratory (National Centre for Antarctic & Ocean Research, India) in frozen condition for further analysis.

The samples were freeze-dried before processing for elemental concentration (%C and %N) and isotopic analysis (δ13C and δ15N) of the sedimentary organic matter (SOM). A portion of the freeze-dried samples were finely ground for homogenization and further sub-sampled into two batches- (i) 2N HCl treated for Total Organic Carbon (TOC) measurement and (ii) untreated for determination of total nitrogen content. Additionally KOBr-KOH treatment was carried out on surface sediments for investigating the role of bound nitrogen present in the deposited sediments. HCl treatment removed carbonate from the sample for TOC and δ13C measurement. 20 ml of 2N HCl solution was added to 500–1000 mg of finely ground sediment. The mixture was swirled and allowed to stand overnight. The sample was then washed with double-distilled water and approximately 5 mg of treated sample was used for TOC and δ13C analysis44. KOBr-KOH treatment oxidizes organic nitrogen fraction, leaving behind bound nitrogen9,45. 6 ml of liquid bromine was added to ice-cooled 2M KOH at 0.5 ml/minute to prepare KOBr-KOH solution. 20 ml of this solution was added to 500–1000 mg of finely ground sediment. 60 ml of double distilled water was added and the mixture was boiled vigourously. After overnight cooling, the sample was washed with 0.5 M KCl to remove released ammonium. Presence of high concentration of potassium throughout the procedure insured that the released ammonium produced during oxidation doesnot bind with the clay present in the sample. The sample was again washed with double-distilled water. Approximately, 180 mg of KOBr-KOH treated sample was used for analysis. For Total Nitrogen concentration (TN) and δ15N measurement, approximately 50 mg of bulk ground sediment was used. Sediments from arctic region have been shown to contain significant amount of bound nitrogen of terrestrial origin9 which gets into the pool by replacing potassium in potassium rich clay minerals46, found in abundance in higher latitudes marine sediments. The organic nitrogen content is obtained by subtracting bound nitrogen content from the total nitrogen. δ15Norganic is obtained using isotopic mass balance ( ). The analysis for elemental concentration and isotopic composition was carried out at the Marine Stable Isotope Laboratory (MASTIL) of National Centre for Antarctic and Ocean Research, Goa, India using an Isoprime Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer in continuous flow mode and coupled to an Elemental Analyser (Isoprime-Vario Isotope Cube) The precision of the organic carbon and nitrogen determinations was 0.31% and 0.24% respectively based on Sulfanilamide as the standard while that of carbon and nitrogen isotopic composition was 0.05‰ and 0.12‰ respectively (1σ standard deviation) based on cellulose (IAEA-CH-3) and ammonium sulphate (IAEA-N-1) as standards.

). The analysis for elemental concentration and isotopic composition was carried out at the Marine Stable Isotope Laboratory (MASTIL) of National Centre for Antarctic and Ocean Research, Goa, India using an Isoprime Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer in continuous flow mode and coupled to an Elemental Analyser (Isoprime-Vario Isotope Cube) The precision of the organic carbon and nitrogen determinations was 0.31% and 0.24% respectively based on Sulfanilamide as the standard while that of carbon and nitrogen isotopic composition was 0.05‰ and 0.12‰ respectively (1σ standard deviation) based on cellulose (IAEA-CH-3) and ammonium sulphate (IAEA-N-1) as standards.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Kumar, V. et al. Evidence of Anomalously Low δ13C of Marine Organic Matter in an Arctic Fjord. Sci. Rep. 6, 36192; doi: 10.1038/srep36192 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Joos, F. et al. Carbon dioxide and climate impulse response functions for the computation of greenhouse gas metrics: a multi-model analysis. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 2793–2825 (2013).

Prather, M. J., Holmes, C. D. & Hsu, J. Reactive greenhouse gas scenarios: Systematic exploration of uncertainties and the role of atmospheric chemistry. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L09803 (2012).

Ciais, P. et al. Carbon and Other Biogeochemical Cycles. Clim. Chang. 2013 - Phys. Sci. Basis 465–570, doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.015 (2013).

Sackett, W. M. The depositional history and isotopic organic carbon composition of marine sediments. Mar. Geol . 2, 173–185 (1964).

Meyers, P. A. Preservation of elemental and isotopic source identification of sedimentary organic matter. Chem. Geol. 114, 289–302 (1994).

Meyers, P. A. Organic geochemical proxies of paleoceanographic, paleolimnologic, and paleoclimatic processes. Org. Geochem. 27, 213–250 (1997).

Meyers, P. A. Applications of organic geochemistry to paleolimnological reconstructions?: a summary of examples from the Laurentian Great Lakes. Org. Geochem . 34, 261–289 (2003).

Stein, R. & MacDonald, R. W. In The Organic Carbon Cycle in the Arctic Ocean (eds. Stein, R. & MacDonald, R. W. ), Ch. 1, 1–32 (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 2004).

Schubert, C. J. & Calvert, S. E. Nitrogen and carbon isotopic composition of marine and terrestrial organic matter in Arctic Ocean sediments: implications for nutrient utilization and organic matter composition. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 48, 789–810 (2001).

Fahl, K. & Stein, R. Biomarkers as organic-carbon-source and environmental indicators in the Late Quaternary Arctic Ocean: problems and perspectives. Mar. Chem. 63, 293–309 (1999).

Peters, K. E. Guidelines for evaluating petroleum source rock using programmed pyrolysis. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull . 70, 318–329 (1986).

Hedges, J. I., Clark, W. a. & Cowie, G. L. Organic matter sources to the water column and surficial sediments of a marine bay. Limnol. Oceanogr. 33, 1116–1136 (1988).

Prahl, F. G., Ertel, J. R., Goni, M. A., Sparrow, M. A. & Eversmeyer, B. Terrestrial organic carbon contributions to sediments on the Washington margin. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 58, 3035–3048 (1994).

Drenzek, N. J., Montluçon, D. B., Yunker, M. B., Macdonald, R. W. & Eglinton, T. I. Constraints on the origin of sedimentary organic carbon in the Beaufort Sea from coupled molecular 13C and 14C measurements. Mar. Chem. 103, 146–162 (2007).

Tolosa, I. et al. Distribution of sterol and fatty alcohol biomarkers in particulate matter from the frontal structure of the Alboran Sea (S.W. Mediterranean Sea). Mar. Chem. 82, 161–183 (2003).

Belicka, L. L. & Harvey, H. R. The sequestration of terrestrial organic carbon in Arctic Ocean sediments: A comparison of methods and implications for regional carbon budgets. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 6231–6248 (2009).

Stein, R. & Macdonald, R. W. In The Organic Carbon Cycle in the Arctic Ocean (eds. Stein, R. & MacDonald, R. W. ) Ch. 8, 315–322, doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-18912-8_8 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2004).

Raymond, P. A., Oh, N.-H., Turner, R. E. & Broussard, W. Anthropogenically enhanced fluxes of water and carbon from the Mississippi River. Nature 451, 449–452 (2008).

Raymond, P. A. & Cole, J. J. Increase in the Export of Alkalinity from North America’s Largest River. Science 301, 88–91 (2003).

Betzer, P. R. et al. Primary productivity and particle fluxes on a transect of the equator at 153°W in the Pacific Ocean. Deep Sea Res. Part A. Oceanogr. Res. Pap . 31, 1–11 (1984).

Naidu, S. A. et al. Organic carbon isotope ratios (δ13C) of Arctic Amerasian Continental shelf sediments. Int. J. Earth Sci. 89, 522–532 (2000).

Tiwari, M., Singh, A. K. & Sinha, D. K. In Chemostratigraphy (ed. Ramkumar, M. ) 65–92, doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-419968-2.00003-0 (Elsevier, 2015).

Teeri, J. A. & Stowe, L. G. Climatic patterns and the distribution of C4 grasses in North America. Oecologia 23, 1–12 (1976).

Goericke, R. & Fry, B. Variations of Marine Plankton Delta-C-13 with Latitude, Temperature, and Dissolved CO2 in the World Ocean. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 8, 85–90 (1994).

Rau, G. H., Riebesell, U. & Wolf-Gladrow, D. CO2 aq-dependent photosynthetic 13C fractionation in the ocean: A model versus measurements. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 11, 267–278 (1997).

Syvitski, J. P. M. & Shaw, J. Chapter 5 Sedimentology and Geomorphology of Fjords. Dev. Sedimentol. 53, 113–178 (1995).

Shetye, S., Mohan, R., Shukla, S. K., Maruthadu, S. & Ravindra, R. Variability of Nonionellina labradorica Dawson in Surface Sediments from Kongsfjorden, West Spitsbergen. Acta Geol. Sin. - English Ed . 85, 549–558 (2011).

Singh, V., Farooqui, A. & Mehrotra, N. Late pleistocene and early holocene climate of Ny-Alesund, Svalbard (Norway): A study based on biological proxies. J. … 78, 109–116 (2011).

MacLachlan, S. E., Cottier, F. R., Austin, W. E. N. & Howe, J. a. The salinity: δ18O water relationship in Kongsfjorden, western Spitsbergen. Polar Res . 26, 160–167 (2007).

Ślubowska, M. A., Koç, N., Rasmussen, T. L. & Klitgaard-Kristensen, D. Changes in the flow of Atlantic water into the Arctic Ocean since the last deglaciation: Evidence from the northern Svalbard continental margin, 80°N. Paleoceanography 20, PA4014 (2005).

Redfield, A. C. On the proportions of organic derivatives in sea water and their relation to the composition of plankton . (University press of liverpool Liverpool, UK, 1934).

Takahashi, T., Broecker, W. S. & Langer, S. Redfield ratio based on chemical data from isopycnal surfaces. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean . 90, 6907–6924 (1985).

Korsun, S. A. & Polyak, L. V. Distribution of benthic foraminiferal morphogroups in the Barents Sea. Okeanologiya 29, 838–844 (1989).

Anderson, T. F. In Stable Isot. Sediment. Geol. 1–151 (Special Publications of SEPM, 1983).

Ehleringer, J. R., Cerling, T. E. & Helliker, B. R. C4 photosynthesis, atmospheric CO2, and climate. Oecologia 112, 285–299 (1997).

Descolas-Gros, C. & Fontugne, M. R. Carbon fixation in marine phytoplankton: carboxylase activities and stable carbon-isotope ratios; physiological and paleoclimatological aspects. Mar. Biol. 87, 1–6 (1985).

Maslin, M. & Swann, G. A. In Isot. Palaeoenvironmental Res. SE - 06 (ed. Leng, M. ) 10, 227–290 (Springer Netherlands, 2006).

Schubert, C. J. & Stein, R. Lipid distribution in surface sediments from the eastern central Arctic Ocean. Mar. Geol. 138, 11–25 (1997).

Stein, R., Grobe, H. & Wahsner, M. Organic carbon, carbonate, and clay mineral distributions in eastern central Arctic Ocean surface sediments. Mar. Geol. 119, 269–285 (1994).

Rossak, B. T., Kassens, H., Lange, H. & Thiede, J. In Land-Ocean Syst. Sib. Arct. (eds. Kassens, H. et al. ) 587–599, doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-60134-7_45 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1999).

Stevenson, F. J. & Cheng, C.-N. Organic geochemistry of the Argentine Basin sediments: Carbon-nitrogen relationships and Quaternary correlations. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 36, 653–671 (1972).

Müller, P. Ratios in Pacific deep-sea sediments: Effect of inorganic ammonium and organic nitrogen compounds sorbed by clays. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 41, 765–776 (1977).

Wada, E. et al. Biogeochemical studies on the transport of organic matter along the Otsuchi River watershed, Japan. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 25, 321–336 (1987).

Galy, V., Bouchez, J. & France-Lanord, C. Determination of Total Organic Carbon Content and δ13C in Carbonate-Rich Detrital Sediments. Geostand. Geoanalytical Res. 31, 199–207 (2007).

Silva, J. A. & Bremner, J. M. Determination and Isotope-Ratio Analysis of Different Forms of Nitrogen in Soils: 5. Fixed Ammonium1. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 30, 587–594 (1966).

Stevenson, F. J. & Dhariwal, A. P. S. Distribution of Fixed Ammonium in Soils1. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J . 23, 121–125 (1959).

Acknowledgements

This is NCAOR Contribution no. 33/2016. The authors thank the Secretary, Ministry of Earth Sciences, Govt. of India and Director, National Centre for Antarctic and Ocean Research for support. We also thank the Indian Arctic field team for their help during sample collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.K. and M.T. envisaged the idea and wrote the paper. M.T. collected the samples and V.K. processed them. Sample analysis was done by S.N. and S.T. (Stable Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer and Elemental Analyzer operations) with inputs towards manuscript writing and figure making. All authors have approved the final article.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, V., Tiwari, M., Nagoji, S. et al. Evidence of Anomalously Low δ13C of Marine Organic Matter in an Arctic Fjord. Sci Rep 6, 36192 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36192

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36192

This article is cited by

-

Exploring bacterial diversity in Arctic fjord sediments: a 16S rRNA–based metabarcoding portrait

Brazilian Journal of Microbiology (2024)

-

Large contributions of petrogenic and aged soil-derived organic carbon to Arctic fjord sediments in Svalbard

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

A study on benthic molluscs and stable isotopes from Kutch, western India reveals early Eocene hyperthermals and pronounced transgression during ETM2 and H2 events

Swiss Journal of Palaeontology (2022)

-

Sources and Fate of Organic Carbon in West Spitsbergen Fjord Systems: A Review

Journal of the Geological Society of India (2022)

-

Abundance and diversity of diazotrophs in the surface sediments of Kongsfjorden, an Arctic fjord

World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.