Abstract

Insects can rapidly adapt to environmental changes through physiological responses. The red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum is widely used as a model insect species. However, the stress–response system of this species remains unclear. Superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) is a crucial antioxidative enzyme that is found in mitochondria. T. castaneum SOD2 (TcSOD2) is composed of 215 amino acids, and has an iron/manganese superoxide dismutase domain. qRT-PCR experiments revealed that TcSOD2 was present through all developmental stages. To evaluate TcSOD2 function in T. castaneum, we performed RNAi and also assessed the phenotype and antioxidative tolerance of the knockdown of TcSOD2 by exposing larvae to paraquat. The administration of paraquat resulted in significantly higher 24-h mortality in TcSOD2 knockdown larval groups than in the control groups. The TcSOD2 knockdown adults moved significantly more slowly, had lower ATP content, and exhibited a different body color from the control groups. We found that TcSOD2 dsRNA treatment in larvae resulted in increased expression of tyrosinase and laccase2 mRNA after 10 days. This is the first report showing that TcSOD2 has an antioxidative function and demonstrates that T. castaneum may use an alternative antioxidative system when the SOD2-based system fails.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Insects are exposed to a wide range of environmental stressors, including ultraviolet radiation from sunlight, high or low temperatures, dry conditions/low humidity, lack of food, external hazards, metamorphosis in holometabolous insects, insecticides, and parasitism. These stressors cause the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the insect’s body1. ROS are the intermediates of oxygen reduction processes such as respiration redox reactions, chemical metabolism, and energy production2. Under normal conditions, ROS can be useful for the body, as they serve as secondary messengers. However, with excessive exposure to stressors, the production of additional ROS leads to oxidative stress.

Environmental conditions can have physiological effects on insect development, aging, growth, longevity, survival, and reproduction1. However, insects can rapidly adapt to environmental changes through physiological responses. For example, the lepidopteran Bombyx mori produces colored cocoons that vary from yellow, through pink, golden-yellow, flesh, sasa (yellowish green), and green. The pigments in the yellow, pink, golden-yellow, and flesh cocoons are derived from carotenoids3, while those in the sasa and green cocoons are from flavonoids4,5. These pigments act as antioxidants, protecting the pupae from sunlight6. Uric acid (UA), which is the final product of purine metabolism, also plays an important role as a physiological antioxidant7. UA accumulates as urate granules in the integument of B. mori, causing a whitening of the color, and also accumulates in the wings of Pieris brassicae8,9, protecting the insect’s body against photooxidative stress10,11. Various types of antioxidant proteins have also been found that regulate the generation of ROS in the body, such as heat shock proteins, superoxide dismutase, DJ-1, and mitogen-activated protein kinase12,13,14,15,16, all of which are conserved among species. Thus, insects employ the diverse strategies for resistance from environmental stressors. As a result, they are well adapted to environmental change.

The red flour beetle (Tribolium castaneum) is a holometabolous insect belonging to the Order Coleoptera. The genome information of this species is well characterized, and systematic RNA interference (RNAi) is available17,18,19,20. We were interested in understanding what process T. castaneum beetles employ to eliminate ROS from their bodies, as well as the mechanisms by which they adapt to environmental change.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is an important antioxidative stress protein that converts the superoxide anion to hydrogen peroxide by acting as a dismutase21. Three types of SOD genes have been annotated in the T. castaneum genomic database (http://beetlebase.org/): TcSOD1, TcSOD2, and TcSOD3. It has been shown that TcSOD1 responds to some type of stress22, and TcSOD3 is also found in T. castaneum, although its function remains unclear23. It is possible that TcSOD2 might be present in the mitochondrial matrix, as occurs in other species and may respond to oxidative stress24. However, the function and characteristics of this protein in T. castaneum are currently unclear. The function of SOD2 has been investigated in Drosophila melanogaster, where it has been found that flies that are deficient in SOD2 have short life spans, weak tolerance to oxidative stress, and abnormal movements25,26.

In this study, we investigated the function and characteristics of TcSOD2 using RNAi. We also evaluated the function of TcSOD2 under oxidative stress using paraquat. We found that TcSOD2 has an antioxidative function and that T. castaneum may have an alternative antioxidative system that can function when the SOD2-based system fails.

Results

Identification and characterization of the TcSOD2 sequence

We obtained the TcSOD2 sequence from BeetleBase using HMM searches, which yielded one SOD2 sequence among T. castaneum genes (Supplementary Table S1). The sequence was annotated as a manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD2) (TC005780) and was localized in ChLG8:9478941…9479642. We confirmed the sequence of TcSOD2 through cDNA cloning, which deduced that the open reading frame was 648 nucleotides long, encoding a protein of 215 amino acids, a molecular weight of 23,642 Da, and a putative isoelectric point of 8.21. TcSOD2 contained an iron/manganese superoxide dismutase alpha-hairpin domain (Sod_Fe_N, pfam; PF00081) at position 18A-99S and an iron/manganese superoxide dismutase C-terminal domain (Sod_Fe_C, pfam; PF02777) at 105P-208R (Supplementary Fig. S1). TcSOD2 showed homology to B. mori SOD2 (AB190802, 68%) and D. melanogaster SOD2 (FBpp0086226, 62%), M. sexta SOD2 (Msex2. 03430-RA, 73%; Msex2. 03430-RB, 70%), and the metal binding amino acid positions were also conserved across these insect species (Supplementary Fig. S1, asterisks). Phylogenetic analysis of TcSOD2, TcSOD1, and TcSOD3 along with the SODs of other insect species placed TcSOD2 in the insect SOD2 cluster (Fig. 1) The nucleotide sequence reported in this paper has been submitted to the GeneBank/DDBJ SAKURA Data bank, Accession No. LC154964.

The multiple-alignment that was used to construct the phylogenetic tree, and the tree view was then used to display the phylogenetic tree. The insect, animal and baby drawings (http://g86.dbcls.jp/~togoriv/) are licensed under the HYPERLINK http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ja Creative Commons display 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ja.

TcSOD2 was expressed through all developmental stages

We examined the mRNA expression of the three types of TcSOD genes in four developmental stages using qRT-PCR. All three SODs mRNA were expressed in all of the developmental stages. Expression of TcSOD2 was decreased in pharate pupal developmental stage, while expression of TcSOD3 was increased in pupal developmental stage (Fig. 2).

Whole bodies were used for qRT-PCR for each developmental stage. Larva, pharate pupa, pupa and adult as Relative Quantification (RQ) values. RQ represents the relative expression level compared to the reference sample. Error bars represent the relative minimum/maximum expression levels about the mean RQ expression level. TcRpS6 was used as endogenous control.

Verification of decreased SOD2 mRNA and activity in TcSOD2 knockdown insects

We designed TcSOD2 dsRNA from cDNA position 1 to 340, and the synthesis of the dsRNA was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The knockdown effect of this dsRNA was verified by qRT-PCR and measurement of SOD activity. The expression of TcSOD2 mRNA was decreased in the TcSOD2 dsRNA-injected groups compared with the TcVer dsRNA-injected control groups (Supplementary Fig. S2). In addition, the total SOD activity and SOD2-specific activity (assessed as MnSOD activity) significantly decreased in the TcSOD2 knockdown group compared with the control group, (Supplementary Fig. S3). Thus, we succeeded to decrease TcSOD2 mRNA and SOD2 activity. TcVer knockdown efficiency was decreased in adult, whereas TcSOD2 knockdown efficiency was continued in adult (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Vulnerability of TcSOD knockdown larvae to paraquat-induced oxidative stress

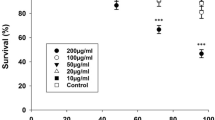

We determined that the LC50 of paraquat was lower in T. castaneum adults than larvae (adults: 9.86 mM, 95% CI = 7.72–12.43; larvae: 25.20 mM, 95% CI = 17.71–36.71). To assess the oxidative stress resistance ability, we employed paraquat-induced oxidative stress in the TcSOD2 knockdown larvae and found that the LC50 of the TcVer knockdown control group was 17.7 mM (95% CI = 9.8–32.2), whereas the LC50 of the TcSOD2 knockdown group was 9.0 mM (95% CI = 3.1–21.7). Thus, the TcSOD2 knockdown group was tend to be vulnerable to paraquat-induced oxidative stress compared with the control.

Movement in TcSOD2 knockdown insects

To evaluate the phenotype of the TcSOD2 knockdown insects, we observed dsRNA-injected insects. Interestingly, we found that TcSOD2 knockdown adults showed abnormal movements compared with TcVer knockdown adults (Supplementary Videos S1 and S2). These adults not only had a much lower average speed than the TcVer knockdown control group (Table 1) but also had a significantly slower running speed, as shown by the light-attracted locomotion assay (Fig. 3). We also found that the ATP content of the TcSOD2 knockdown insects was significantly lower than the TcVer knockdown control group (P = 0.001; Fig. 4).

Other phenotypic changes in TcSOD2 knockdown adults

We observed the survival of T. castaneum adults for 60 days and found that the TcSOD2 knockdown group had significantly lower survival than the TcVer control group (Table 2).

Unexpectedly, we also found that the body color of TcSOD2 knockdown adults was dark brown from 1 day after adult ecdysis, in contrast to the reddish brown color of control beetles (Fig. 5). This body color change suggested an increase in melanin in the cuticle. In addition, we observed an increase in expression of tyrosinase 1 and 2, and also in laccase2A, a laccase2 splicing isoform, all potentially involved in oxidation of catechols leading to increased melanin synthesis in the TcSOD2 knockdown larvae (Fig. 6). Expression of tyrosine hydroxylase, required for production of melanin precursors, was little bit affected by TcSOD2 knockdown.

The dsRNA-treated whole body was used for qRT-PCR. TcVer dsRNA-injected larva and TcSOD2 dsRNA-injected larva as Relative Quantification (RQ) values. RQ represents the relative expression level compared to the reference sample. Error bars represent the relative minimum/maximum expression levels about the mean RQ expression level. Lac2A, T. castaneum laccase 2A; Lac2B, T. castaneum laccase 2B; TH, T. castaneum tyrosine hydroxylase; Tyro1, T. castaneum tyrosinase1; Tyro2, T. castaneum tyrosinase2; TcRpS6 was used as endogenous control.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the function of TcSOD2 in T. castaneum. The metal binding amino acid residues of TcSOD2 were well conserved in the three model insect species investigated, and the phylogenetic tree showed that TcSOD2 is present in the SOD2 cluster, and four insect species SOD2 were closely related.

Paraquat inhibits mitochondrial complex I, leading to generation of ROS27,28. SOD2 in other species plays a role in removing ROS that have been generated in the mitochondria during ATP production29. In this study, the TcSOD2 knockdown larvae were tend to vulnerable to paraquat-induced oxidative stress, and the TcSOD2 knockdown adults had a short life span compare to TcVer knockdown control group. In addition, we observed that the TcSOD2 knockdown adults walked and ran much more slowly than the TcVer knockdown control group and also had a significantly lower ATP content, consistent with a defect in mitochondrial function.

When we assessed the running speed in the paraquat treatment group with a light-attracted locomotion assay (Supplementary Fig. S4), the running speed of the paraquat treatment group was slower than the control (1% sucrose treatment). Similarly, paraquat treatment of D. melanogaster adults resulted in decreased the climbing speed on the vial wall in negative geotaxis assay, because generated ROS caused mitochondrial dysfunction30.

Our result showed the TcSOD2 knockdown beetles were much slower than the Tcver group (Fig. 3). These results are consistent with a hypothesis that TcSOD2 plays a role in removing ROS that have been generated in the mitochondria and that lack of TcSOD2 results in oxidative stress and impaired mitochondrial function.

A previous study showed that Sod2 −/− mice (Mus musculus) had short life spans (the mean life span was 5.6 days) and experienced cardiomyopathy31. Similarly, SOD2 knockdown D. melanogaster have been shown to have short life spans (around 10 days from adult onset), abnormal motion, and a weak tolerance to oxidative stress32. While SOD2 null flies died within 24 hr of adult eclosion and had reduced expression of SOD1 mRNA25. We found that 56.5% of TcSOD2 knockdown adults died by day 5, but some beetles survived until day 40 (Table 2). Furthermore, the expression of other TcSODs also slightly increased in TcSOD2 knockdown larvae, and the expression level of TcSOD1 and TcSOD3 was the same in TcSOD2 knockdown adults as in TcVer knockdown adults. Thus, it may be that other SODs compensate for the TcSOD2 function

SOD2 knockdown Caenorhabditis elegans had lower levels of egg production and a weak tolerance to oxidative stress33. In B. mori, SOD2 may play a role in antioxidative stress tolerance in fifth instar larvae; however, it is not clear whether SOD2 also affects the life span and movement in this species14. The function of SOD2 for antioxidative stress tolerance in the mitochondria has apparently been conserved from arthropods to mammals.

Interestingly, we found that TcSOD2 knockdown adults had a novel phenotype, exhibiting a black-brown color body. Such a phenotypic change has not been found in any previous SOD2 knockdown study. Sichel et al.34 previously reported that Xenopus laevis livers were stained with melanin, and that SOD1, SOD3, and SOD2 activities were lower in normal animals than in albino mutants. Consequently, they suggested that melanin has a similar role to SODs, because it is able to scavenge superoxide anions, providing the animal with some antioxidative tolerance34. Therefore, it is possible that increased melanin synthesis may have been stimulated in the TcSOD knockdown beetles, to serve as an antioxidant by scavenging superoxide anions as an alternative protective response. A black-brown body color in T. castaneum might be caused by an increased melanin content35,36. Since TcSOD2 knockdown beetles did not exhibit the reduced longevity observed in other SOD2 knockdown model organisms, this increased melanin content may help to increase their survival time. To further investigate the body color of the TcSOD2 knockdown adults, we used qRT-PCR to examine the relationship between TcSOD2 and the following melanin synthesis-related genes: tyrosine hydroxylase, tyrosinase1, tyrosinase2, laccase 2A and laccase 2B. We found that the expression of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA slightly differ between the TcSOD2 knockdown group and the TcVer knockdown control group. However, the expression of tyrosinase1, tyrosinase2 and laccase 2 A mRNA increased in TcSOD2 knockdown larvae. Laccase 2A contribute a major cuticle tanning through all developmental stages in T. castaneum36. Although the role of tyrosinase in cuticle pigmentation is not well established, it is possible that an increased concentration of tyrosinase is responsible for the darker body color of SOD2 knockdown adults.

In conclusion, in this study we examined the function of TcSOD2 and found that it has a conserved antioxidative function across species. We also found that the loss of function of TcSOD2 leads to an alternative, potentially compensating antioxidative system in T. castaneum. Therefore, we have elucidated a possible mechanism by which these insects can rapidly adapt to changes in their environmental conditions. In a future study, we will investigate the molecular mechanisms by which TcSOD2 may control melanin synthesis in T. castaneum.

Methods

Insects

The T. castaneum GA-1 strain was used in all experiments. Insects were reared on whole wheat flour containing 5% brewer’s yeast37. All insects were kept at 30 °C on a 16-h light/8-h dark cycle.

Identification of the TcSOD2 sequence by HMM search and Bioinformatics analysis

The hmmsearch program in HMMER (Version 3.1b2)38 was used to detect TcSOD2 candidates. Hidden Markov model (HMM) profiles of the SOD2 N-terminal domain (Sod_Fe_N: PF00081.18) and SOD2 C-terminal domain (Sod_Fe_C: PF02777.14) in the Pfam 28.0 database39 were used as queries against protein sequences in the T. castaneum Tcas3 Gene Set (ftp://ftp.bioinformatics.ksu.edu/pub/BeetleBase/3.0/) with default parameters.

A search for SOD orthologs in D. melanogaster and B. mori was conducted using BLAST methods. Global homology searches were conducted using Genetyx ver. 11 (Genetyx Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Alignment of the deduced TcSOD2 amino acid sequences and SOD homologs from other species and phylogenetic analysis were performed using DDBJ ClustalW 2.040,41. The multiple-alignment that was used to construct the phylogenetic tree is presented in Fig. 1. Tree view (http://taxonomy.zoology.gla.ac.uk/rod/treeview.html) was then used to display the phylogenetic tree. Sequences are presented for all SODs obtained from a public database (Supplementary Table S1). A protein motif search was conducted using SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/).

Purification of total RNA and cDNA synthesis from whole-body samples

Whole bodies of larvae, pharate pupae, pupae, and adults (n = 5 per stage) were used for total RNA purification.

These samples were stored at −80 °C until use. These whole bodies were weighed and homogenized with lysis buffer from the PureLink® RNA extraction kit (Thermofisher Scientific Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) and then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min, following which the supernatants were collected and processed for RNA purification according to the manufacturer’s instructions. First, 1 μg of total RNA was treated with DNase I (Invitrogen, Van Allen Way, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and then 500 ng of DNase-treated total RNA was used as template for cDNA synthesis using a PrimeScript™ 1st strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara co. ltd, Tokyo, Japan). Quantitative real time-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed in 20 μl reaction volumes with 0.125 μl of cDNA template and the specific primers (Supplementary Table 3) with a KAPA SYBR Fast qRT-PCR Kit (Nippon Genetics co, ltd., Tokyo, Japan), in accordance to manufacturer instructions. qRT-PCR was performed on a Step One plus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems Foster City, CA) following the Delta-Delta Ct method. The T. castaneum ribosomal protein S6 gene (RpS6, Gene ID 288869507) was utilized as an endogenous reference against which RNA expression levels were standardized, and all data were calibrated against universal reference data. Relative quantification (RQ) values represent the relative expression level against a reference sample. All sample sets were assayed in triplicate as technical replications.

cDNA cloning for TcSOD2 showed in supplementary information section.

cDNA cloning of TcSOD2 for the synthesis of dsRNA and evaluation of the phenotype

To evaluate the dsRNAs for possible off-target effects, we used the E-RNAi web-service (http://www.dkfz.de/signaling/e-rnai3/). TcSOD2 dsRNA generated 297 nineteen-nucleotide-long efficient siRNAs that matched TcSOD2. However, the E-RNAi identified no off-targets of dsTcSOD2. To produce synthesized TcSOD2 dsRNA, 340 bp of the target site were amplified by PCR using the T. castaneum larval cDNA library. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table S4. This fragment was cloned into the PCR vector pMiniT (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and sequenced.

T. castaneum vermillion (TcVer, GenBank AY052390) was used as a negative control. TcVer dsRNA was synthesized according to the methods of Arakane et al.42 using the MEGAscript RNAi kit (Ambion), according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

T. castaneum larvae (the larva was separated according to size using a No. 25 sieve (Thermo Fisher inc.) were injected with 400–600 ng/200 nl of dsRNAs using a microinjection system (Nanoliter 2000 and Micro4 controller) under a stereomicroscope. We then performed qRT-PCR with the specific primers (Supplementary Table S3 and S5) on the larvae and adults at days 5 and 25 after dsRNA injection, respectively, to assess the knockdown efficiency for the target genes. In addition, we monitored the phenotype of each group over a 2-month period. To evaluate adult survivorship, we counted the number of live insects for 2 months starting from adult day 0 and then calculated the adult survival days.

Determination of the LC50 of paraquat in T. castaneum

To determine the LC50 (the concentration at which half of the treated individuals are killed) of paraquat in larval and adult T. castaneum, we administered paraquat to larvae (the larva was separated by size with 15 inch serve; n = 10) or adults (n = 20), TcVer knock down larvae (n = 5) and TcSOD2 knock down larvae (n = 5) using the following procedure. These larvae were used 11 days after dsRNA injection. A 1 cm diameter filter paper was placed in a 3.5 cm diameter Falcon culture dish (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Each 1 cm filter paper was then saturated with 70 μl of 0, 1.56, 3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, or 100 mM paraquat in 1% sucrose solution. The insects were starved overnight before administering paraquat. The number of dead insects after 24 h was counted, and the mortality rate was calculated as % mortality = (X/Y) × 100, where X = the number of dead insects in the group and Y = the total number of insects in the group. LC50 was calculated by using the Probit Analysis43 option in the JMP 10.0 software package (SAS Institute Japan Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Measurement of SOD activity

To assay the SOD activity in insects with a loss of function of TcSOD2, an SOD assay kit was used (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA). These larvae were used 10 days after dsRNA injection. The whole bodies of larvae (n = 3) were homogenized with 200 μl of homogenized buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)) on ice. The homogenate was then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C, following which the supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and total SOD activity was measured. SOD2 activity was measured by adding 100 mM KCN to the homogenate samples (final concentration of KCN = 1 mM).

Measurement of adenosine triphosphate concentration

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) was determined using an ATP Bioluminescence Assay Kit CLS II (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany). The whole bodies of adults that had been injected with each dsRNA after 25 days (n = 3) were weighed and then homogenized with 200 μl of boiling 100 mM Tris-HCl and 4 mM EDTA buffer (pH 7.75). The homogenate was incubated for 2 min at 100 °C and then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature, following which the supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and ATP was measured according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The emission of luciferase was detected by a multiple wavelength plate reader (Molecular Devices Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The ATP concentration was then determined using standard curve data.

Protein assay

The total protein concentration was determined using a Micro BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA).

Light-attracted locomotion assay and evaluation of speed

T. castaneum adults that had been injected with each dsRNA after 25 days (n = 10) were placed on the bottom of a 14-ml Falcon culture polystyrene tube (BD Biosciences) in a dark room, following which the tube was immediately laid down and fixed to the surface using double-sided tape. These adults were attracted to a light that was shone on the side of the cap of the tube (Supplementary Video S3). We measured the time that T. castaneum adults took to travel from the bottom of the tube to the cap and repeated this five times per group. Any individuals that showed aberrant behaviors (mating or did not move) were omitted from the dataset. The movement of the adults were also recorded by video, following which their walking speed was analyzed using Image J with wrMTrck plugin44.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Tabunoki, H. et al. Superoxide dismutase 2 knockdown leads to defects in locomotor activity, sensitivity to paraquat, and increased cuticle pigmentation in Tribolium castaneum. Sci. Rep. 6, 29583; doi: 10.1038/srep29583 (2016).

Accession codes

References

Korsloot, A., Gestel, C. A. M. & Straalen, N. M. Environmental stress and cellular response in arthropods. 19–76 (CRC press, 2004).

Yu, B. P. Cellular defenses against damage from reactive oxygen species. Physiological reviews 74, 139–162 (1994).

Harizuka, M. Physiological genetics of the carotenoids in Bombyx mori, with special reference to the pink cocoon. Bull. Sericul. Exp. Stat. 14, 141–156 (1953).

Tamura, Y., Nakajima, K., Nagayasu, K. & Takabayashi, C. Flavonoid 5-glucosides from the cocoon shell of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Phytochemistry 59, 275–278 (2002).

Kurioka, A. & Yamazaki, M. Purification and identification of flavonoids from the yellow green cocoon shell (Sasamayu) of the silkworm, Bombyx mori Biosci. Biotechnol.Biochem. 66, 1396–1399 (2002).

Daimon, T. et al. The silkworm Green b locus encodes a quercetin 5-O-glucosyltransferase that produces green cocoons with UV-shielding properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107, 11471–11476 (2010).

Ames, B. N., Cathcart, R., Schwiers, E. & Hochstein, P. Uric acid provides an antioxidant defense in humans against oxidant- and radical- caused aging and cancer: A hypothesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78, 6858–6862 (1981).

Hayashi, Y. Xanthine dehydrogenase in the silkworm Bombyx mori L. Nature 186, 1053–1054 (1960).

Tojo, S. & Yushima, T. Uric acid and its metabolites in butterfly wings. J. insect physiol. 18, 403–422 (1972).

Matsuo, T. & Ishikawa, Y. Protective role of uric acid against photooxidative stress in the silkworm, Bombyx mori (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 34, 481–484 (1999).

Lafont, R. & Pennetier, J.-L. Uric acid metabolism during pupal-adult development of Pieris brassicae . J. insect physiol. 21, 1323–1336 (1975).

Li, Q. R. et al. Analysis of midgut gene expression profiles from different silkworm varieties after exposure to high temperature. Gene. 549, 85–96 (2014).

Moribe, Y., Oka, K., Niimi, T., Yamashita, O. & Yaginuma, T. Expression of heat shock protein 70a mRNA in Bombyx mori diapause eggs. J Insect Physiol. 56, 1246–1252 (2010).

Nojima, Y. et al. Superoxide dismutases, SOD1 and SOD2, play a distinct role in the fat body during pupation in silkworm Bombyx mori . PLoS One. 10, e0116007 (2015).

Tabunoki, H. et al. BmDJ-1 is a key regulator of oxidative modification in the development of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. PLoS One. 6, e17683 (2011).

Fujiwara, Y., Shindome, C., Takeda, M. & Shiomi, K. The roles of ERK and P38 MAPK signaling cascades on embryonic diapause initiation and termination of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 36, 47–53 (2006).

Kim, H. S. et al. BeetleBase in 2010: revisions to provide comprehensive genomic information for Tribolium castaneum . Nucleic Acids Res. 38 (Database issue), D437–D442(2010).

Tribolium Genome Sequencing Consortium. The genome of the model beetle and pest Tribolium castaneum . Nature 452, 949–955 (2008).

Knorr, E., Bingsohn, L., Kanost, M. R. & Vilcinskas, A. Tribolium castaneum as a model for high-throughput RNAi screening. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 136, 163–178 (2013).

Schmitt-Engel, C. et al. The iBeetle large-scale RNAi screen reveals gene functions for insect development and physiology. Nat Commun. 6, 7822 (2015).

Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutases. Annual Review of Biochemistry 44, 147–159 (1975).

Kiyotake, H. et al. Gain of long tonic immobility behavioral trait causes the red flour beetle to reduce anti-stress capacity. J Insect Physiol. 60, 92–97 (2014).

Zhang, J., Lu, A., Kong, L., Zhang, Q. & Ling, E. Functional analysis of insect molting fluid proteins on the protection and regulation of ecdysis. J Biol Chem. 289, 35891–35906 (2014).

Landis, G. N. & Tower, J. Superoxide dismutase evolution and life span regulation. Mech Ageing Dev. 126, 365–379 (2005).

Duttaroy, A., Paul, A., Kundu, M. & Belton, A. A Sod2 null mutation confers severely reduced adult life span in Drosophila . Genetics. 165, 2295–2299 (2003).

Sun, Y., Yolitz, J., Alberico, T., Sun, X. & Zou, S. Lifespan extension by cranberry supplementation partially requires SOD2 and is life stage independent. Exp Gerontol. 50, 57–63 (2014).

Bove, J., Prou, D., Perier, C. & Przedborski, S. Toxin-induced models of Parkinson’s disease. NeuroRx 2, 484–494 (2005).

Terzioglu, M. & Galter, D. Parkinson’s disease: genetic versus toxin-induced rodent models. FEBS J 275, 1384–1391 (2008).

Salin, K., Auer, S. K., Rey, B., Selman, C. & Metcalfe, N. B. Variation in the link between oxygen consumption and ATP production, and its relevance for animal performance. Proc Biol Sci. 282, 20151028 (2015).

Chaudhuri, A. et al. Interaction of genetic and environmental factors in a Drosophila parkinsonism model. J Neurosci. 27, 2457–2467 (2007).

Huang, T. T. et al. The use of transgenic and mutant mice to study oxygen free radical metabolism. Ann N Y Acad Sci 893, 95–112 (1999).

Kirby, K., Hu, J., Hilliker, A. J. & Phillips, J. P. RNA interference-mediated silencing of Sod2 in Drosophila leads to early adult-onset mortality and elevated endogenous oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99, 16162–16167 (2002).

Gruber, J., Ng, L. F., Fong, S., Wong, Y. T. & Koh, S. A. Mitochondrial changes in aging Caenorhabditis elegans–what do we learn from superoxide dismutase knockouts? PLoS One. 6, e19444 (2011).

Corsaro, C., Scalia, M., Blanco, A. R., Aiello, I. & Sichel, G. Melanins in physiological conditions protect against lipoperoxidation. A study on albino and pigmented Xenopus. Pigment Cell Res. 5, 279–282 (1995).

Gorman, M. J. & Arakane, Y. Tyrosine hydroxylase is required for cuticle sclerotization and pigmentation in Tribolium castaneum Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 40, 267–273 (2010).

Arakane, Y., Muthukrishnan, S., Beeman, R. W., Kanost, M. R. & Kramer, K. J. Laccase 2 is the phenoloxidase gene required for beetle cuticle tanning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 11337–11342 (2005).

Lasley, E. L. et al. Tribolium information bulletin No.3. 3–13 ( William, H. Minter Agricultural research institute, Chazy, NewYork. 1960).

Finn, R. D., Clements, J. & Eddy, S. R. HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 39 (Web Server issue), W29–W37 (2011).

Finn, R. D. et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 (Database issue), D222–D230 (2013).

Larkin, M. A. et al. ClustalW and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 23, 2947–2948 (2007).

Horn, T. & Boutros, M. E-RNAi: a web application for the multi-species design of RNAi reagents–2010 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 38 (Web Server issue), W332–W339 (2010).

Arakane, Y. et al. Molecular and functional analyses of amino acid decarboxylases involved in cuticle tanning in Tribolium castaneum . J Biol Chem. 284, 16584–16594 (2009).

Finny, D. J. Probit Analysis: A Statistical Treatment of the Sigmoid Response Curve. Cambridge University Press, : Cambridge, NY,. 19–20 (1947).

Nussbaum-Krammer, C. I., Neto, M. F., Brielmann, R. M., Pedersen, J. S. & Morimoto, R. I. Investigating the spreading and toxicity of prion-like proteins using the metazoan model organism C. elegans . J Vis Exp. 95, e52321 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Subbaratnam Muthukrishnan and Prof. Yasuyuki Arakane for advice of T. castaneum RNAi experiment; Dr. Richard W. Beeman for advice of T. castaneum paraquat treatment experiment; Prof. Erica Geisbrecht and Mr. David Brooks for advice of using WrMTrck; Prof. Kikuo Iwabuchi, Prof. Takeshi Yokoyama, Prof. Katsuhiko Ito, Prof. Hidemasa Bono, Dr. Daisuke Takahashi, and Dr. Kozo Tshuchida for helpful discussions. Also, we thank Ms. Lisa Brummett for helping with some RNAi experiments. This work was supported by Science and Technology of Japan and Overseas travel assistance program supported by TUAT president discretionary expenses to HT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments H.T. and M.R.K. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools M.J.G., N.T.D. and M.R.K. Performed the experiments H.T. Analyzed the data H.T., M.J.G., N.T.D. and M.R.K. Contributed to the writing of the paper H.T., M.J.G., N.T.D. and M.R.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Tabunoki, H., Gorman, M., Dittmer, N. et al. Superoxide dismutase 2 knockdown leads to defects in locomotor activity, sensitivity to paraquat, and increased cuticle pigmentation in Tribolium castaneum. Sci Rep 6, 29583 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29583

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29583

This article is cited by

-

Transcriptomic comparison between populations selected for higher and lower mobility in the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Lead (Pb)-induced oxidative stress mediates sex-specific autistic-like behaviour in Drosophila melanogaster

Molecular Neurobiology (2021)

-

Effects of RNAi-based silencing of chitin synthase gene on moulting and fecundity in pea aphids (Acyrthosiphon pisum)

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Superoxide dismutase down-regulation and the oxidative stress is required to initiate pupation in Bombyx mori

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Molecular characterization of class I histone deacetylases and their expression in response to thermal and oxidative stresses in the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum

Genetica (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.