Abstract

Targeting hard-to-reach/marginalized populations is essential for preventing HIV-transmission. A unique opportunity to identify such populations in Switzerland is provided by a database of all genotypic-resistance-tests from Switzerland, including both sequences from the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS) and non-cohort sequences. A phylogenetic tree was built using 11,127 SHCS and 2,875 Swiss non-SHCS sequences. Demographics were imputed for non-SHCS patients using a phylogenetic proximity approach. Factors associated with non-cohort outbreaks were determined using logistic regression. Non-B subtype (univariable odds-ratio (OR): 1.9; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.8–2.1), female gender (OR: 1.6; 95% CI: 1.4–1.7), black ethnicity (OR: 1.9; 95% CI: 1.7–2.1) and heterosexual transmission group (OR:1.8; 95% CI: 1.6–2.0), were all associated with underrepresentation in the SHCS. We found 344 purely non-SHCS transmission clusters, however, these outbreaks were small (median 2, maximum 7 patients) with a strong overlap with the SHCS’. 65% of non-SHCS sequences were part of clusters composed of >= 50% SHCS sequences. Our data suggests that marginalized-populations are underrepresented in the SHCS. However, the limited size of outbreaks among non-SHCS patients in-care implies that no major HIV outbreak in Switzerland was missed by the SHCS surveillance. This study demonstrates the potential of sequence data to assess and extend the scope of infectious-disease surveillance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the key challenges in HIV surveillance and more generally in infectious-disease epidemiology is that the sampled or surveyed population might not be representative of the target population, especially with respect to hard-to-reach/marginalized subgroups1,2. The Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS) is one of the most comprehensive HIV cohorts, with an estimated coverage of at least 45% of the cumulative number of HIV-infected individuals in Switzerland, approximately 75% of HIV-patients on antiretroviral treatment, and as much as 80% of AIDS cases3. However, since enrolment into the SHCS is voluntary, the possibility remains that marginalized populations are underrepresented and that entire sub-epidemics might be missed by the cohort2,4.

These issues are particularly important in the context of late presentation of HIV patients, which is a known public health challenge worldwide. Marginalized populations have been shown to be prone to present late as demonstrated in the UK5 and Europe in general6. Late presentation is one of the hurdles against “treatment-as-prevention” efforts on the population scale7. Therefore, marginalized populations present a prime target for intervention and knowing their characteristics would help tailor better interventions8.

A unique opportunity to assess the presence of such “under-the-radar” populations is provided by genotypic resistance testing, which is universal in most industrialized countries (i.e. virtually every patient in care receives a resistance test). In our case, we use for Switzerland a database of all genotypic resistance tests (GRT) performed in Switzerland. This database includes both cohort and non-cohort patients and has been initiated by the Swiss-Federal-Social-Insurance Office (“BSV”) as a quality-control measure for HIV genotyping. All Swiss Laboratories which perform routine HIV resistance tests are obliged to submit sequence data along with minimal demographic information for patient de-duplication, into this database, which therefore contains also sequence data for patients that are not enrolled in the SHCS.

This uniquely complete sequence database allows for the assessment of how well the Swiss HIV epidemic is covered by the SHCS. Both an overall good representation and occasional representation gaps appear plausible for this setting: On the one hand, the very high coverage and systematic long-term follow-up of the SHCS argues for a very high representativeness; on the other hand, populations that fear deportation, persecution, or social rejection might be less willing to participate in cohorts9.

Molecular phylodynamics10 has been used extensively in the recent years to evaluate several features of epidemics11, with HIV being one of the more studied viruses in Switzerland12 Europe13, and the rest of the world14. We aim to further investigate the utility of sequence data (which is being rapidly accumulated worldwide) in extending the scope of epidemiological analysis and to assess the unavoidable gaps arising in classical epidemiological surveillance with a focus on marginalized populations (in this study: all patients facing barriers for enrolment). We leverage the versatile tool of molecular phylodynamics to examine whether cohort and non-cohort patients differ with respect to demographics, whether non-cohort patients constitute entire missed outbreaks, and whether missing demographic information can be inferred from clustering patterns.

Results

We obtained 4,294 non-SHCS HIV sequences from the BSV database collected between 2003 and 2014, of those, 879 were deemed potential duplicates of SHCS patients and thus discarded. Of the remaining 3415, only the first sequence per patient was retained using the workflow delineated in the methods, for a total of 2875 non-SHCS sequences.

The resulting 2,875 non-SHCS sequences were added to the first sequence from the 11,127 SHCS patients with available sequences (out of 18,688 SHCS enrolled patients as of December 2014) for a total of 14,002 Swiss sequences (Table 1). These sequences were then used along with >27,000 background sequences (from the Los Alamos HIV sequence database, see methods) to construct a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree.

Demographics analysis

SHCS collected demographics

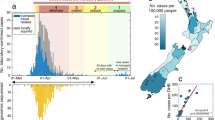

We found that SHCS patients differ from non-cohort patients (with a sequence, hereafter referred to as non-cohort or non-SHCS for simplicity) in terms of viral subtype and demographics (Tables 1 and 2). SHCS patients were 29% females, compared to 36% in the non-SHCS. Thus, women were overrepresented among non-SHCS patients (univariable odds ratio (OR) 1.6; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.4, 1.7),). In regards to subtypes (Fig. 1), univariable analysis showed that non-B subtypes were overrepresented among non-SHCS patients (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.8, 2.1).

Sequence based demographics inference

In order to determine transmission-group and ethnicity for non-cohort patients, we utilized phylogenetic clustering with cohort patients (for whom these demographic variables are known, see methods). This approach is based on the fact that patients in the same phylogenetic cluster tend to exhibit similar demography15. The method was validated by testing its predictive power on two subsets of cohort-sequences with known demographics (a random sample from the SHCS and a group of late enrollers, see methods).

Overall, the inference method performed well (up to 81% correct predictions), yet the performance was dependent on the demographic feature predicted and the genetic distance (i.e. the comprehensiveness of sampling and the consequent tightness of social clusters). More complex models (Support vector machines) improved prediction by 3–6%, when taking into account the inferred demographic, the larger cluster demographics distribution, cluster size, and overall genetic distance (results not shown).

The inferred demographics of the non-SHCS individuals were then compared to that of the SHCS (Table 2). In univariable analysis, we found an overrepresentation of heterosexuals (HET) (OR 1.80, 95% CI 1.63, 1.99; compared to MSM), and intravenous drug users (IDU) (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.52, 2.1) in the non-SHCS, while other transmission-groups were not significantly different between the two populations. Black ethnicity was overrepresented among non-SHCS patients (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.7, 2.1), while other ethnicities showed no difference. This finding is consistent with the above observation of non-B subtypes being more frequent in non-SHCS patients than in the SHCS, given that non-B subtypes are highly correlated with non-white ethnicities. All the covariates were similar in magnitude and significance in a multivariate model as well (Table 2).

Overall, these analyses reveal a robust overrepresentation of non-B (not imputed) subtypes and non-MSM transmission groups (imputed) among patients not enrolled in the cohort.

Clusters Analysis

To shed light on possible clusters of patients that are not enrolled in the SHCS we focused on clusters that were predominantly Swiss (>=80% SHCS and non-SHCS) without imposing bootstrap-support or genetic-distance criteria12. As previously suggested, such transmission clusters can be interpreted as separate introductions of HIV-1 into Switzerland12. Alternative cluster definitions exhibited similar patterns (data not shown).

Cluster size distribution and clustering pattern comparison

We found a similar degree of clustering among SHCS and non-SHCS Swiss patients and a strong intermixing between the two populations. 1,645 clusters were composed of >= 80% Swiss sequences, encompassing 8,135 (73%) of the SHCS sequences, and 1,938 (67%) non-SHCS sequences. The median cluster size was 2 with an interquartile range between two and five (Figure S1).

Most non-SHCS patients belonged to mixed clusters (of SHCS and non-SHCS sequences) indicating a strong mixing between SHCS and non-SHCS patients. Specifically, 65% of clustered non-SHCS patients (1253) were part of outbreaks that consisted of >= 50% SHCS sequences (this threshold was chosen to account for the fact that the median cluster size is two).

Factors determining predominantly Swiss clusters

Univariable analyses revealed that non-SHCS Swiss sequences were less likely to be part of a Swiss transmission cluster in comparison to SHCS sequences (OR 0.8, 95% CI 0.7, 0.9) however this association was not robust for adjustment (OR 1.0, 95% CI 0.9, 1.1). In both univariable and multivariable analysis, non-B subtype significantly decreased the chances of being in a cluster (OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.25, 0.29), which was similarly reflected in black ethnicity and other non-white ethnicities having similarly lower odds of clustering. The only consistent association of transmission group was that IDUs were more likely to cluster than other transmission groups, while HETs and other transmission groups showed no significant associations (all compared to MSM) (Table 3).

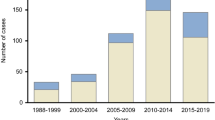

Characteristics of purely non-SHCS clusters

Importantly, we found 344 transmission clusters consisting only of non-SHCS patients. These clusters occurred frequently but were limited in size (Fig. 2) with a median size of 2 patients, IQR: 2–2 and a maximum cluster of seven patients, thus suggesting a strong overlap between transmission chains among SHCS and non-SHCS populations. In particular, this implies the absence of long transmission chains in Switzerland occurring completely outside the SHCS. Finally, there were no apparent subtypes or demographical factors driving the non-SHCS outbreaks (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study we used a database containing all GRTs performed in Switzerland (since 2003) to evaluate the coverage-especially systematic gaps in the coverage-of the SHCS. Despite having an overall excellent coverage (79% of GRTs were from SHCS patients), we found that non-SHCS patients deviate in terms of demographics in comparison to SHCS patients. The most significant of these differences was an overrepresentation of non-B subtypes among non-SHCS patients. As non-B subtypes dominate in Africa and east Asia16, and as these subtypes exhibit a low degree of clustering in our data, this suggests that patients who acquired the infection abroad or from persons originating from those geographical regions, are less likely to enroll in the cohort. Accordingly, we also found that black ethnicity was more frequent among non-SHCS patients. These differences in subtype distribution and ethnicity indicate that hard-to-reach, marginalized populations, or individuals infected abroad were less likely to enrol in the SHCS compared to Swiss or individuals infected in Switzerland. Our results also emphasises the deep intermingling between the two populations, as 65% of non-SHCS patients were within SHCS outbreaks. In summary, non-SHCS patients do not seem to play a significant role in sustaining HIV transmission outside of the cohort, but have significant contributions toward the propagation of non-B subtypes in Switzerland.

As part of the growing understanding that migrants and refugees, especially from HIV-endemic countries are a vulnerable population with specific health needs, the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health is currently conducting a survey among Sub-Saharan African population in Switzerland to map and characterize the needs and attitudes of this population (http://afric-answer.weebly.com/, accessed 1/02/2016). Our work further emphasizes that stigmatization, criminalization, and racial discrimination of patients with HIV are potential obstacles in the battle against the HIV pandemic9.

Our sequence-based approach also validated previous independently-derived results about the representativeness of the SHCS3,17. Our finding that overall 79% of patients with a GRT are enrolled in the SHCS, agrees with previous studies3 showing that approximately 75% of patients on ART in Switzerland are in the SHCS. Furthermore, we also found an underrepresentation of non-B subtypes, which is in good qualitative and quantitative agreement with the results from previous studies who also found that migrants were less likely to enrol in the SHCS4,18.

Despite the differences in the demographics and subtypes, there was no evidence of large outbreaks consisting of purely non-cohort patients (we found a single maximal cluster of 7 patients) (Fig. 2). Theoretically, one cannot rule out that the absence of larger clusters is caused by systematic sample collection bias (for GRTs) that only captures far linked parts of transmission chains, thus leading to smaller observed clusters19. However, this is highly unlikely given the universal coverage of the Swiss Health Care System, the fact that genotypic drug resistance testing is part of the standard of care, and the high probability that patients will seek care when they reach the AIDS phase (or often earlier). Furthermore, even for subtype CRF02_AG, the subtype with the worst representativeness, 57% of patients with GRT are enrolled in the SHCS (Table 1), and non-SHCS clusters are characterized by similar demographics than Swiss-transmission clusters in general. Altogether, this indicates that the sampling gaps of the SHCS are not substantial and even sub-epidemics containing non-enrollers are covered (at the very least, partly).

It should be noted that not all HIV positive patients have a genotypic HIV resistance test; thus, there may be fraction of diagnosed patients that are not part of the BSV database and hence not in our study population. For example, there may be a tendency to obtain resistance testing preferentially for patients that are considered eligible for treatment because of low CD4 cell counts, or pregnancy. However, it is likely that such effects have decreased in recent years, as GRTs close to the time of diagnosis have become the standard of care in Switzerland since approximately 2003. In addition, a large part of non-SHCS patients is also cared for in the SHCS centres, thus the same high medical standards are in place for this population and thus no bias towards less resistance testing is expected4. Thus the population of patients with a GRT corresponds closely to the population of HIV-patients in care and especially to the population of patients on ART.

We employed a BLAST-based method to retrieve background sequences. The study’s outcomes were unchanged compared to including the entire Los Alamos pol sequences (results not shown). Using fewer sequences allowed for smaller trees that take less computational time to be built, thus enabling running the analysis several times as new sequences are added to the SHCS drug resistance database.

In this study, we utilized a liberal cluster definition (80% Swiss with no bootstrap support or genetic distance limitations), which allowed us to capture the maximal number of outbreaks from non-SHCS patients. For the purpose of this study (i.e. excluding large outbreaks among non-cohort patients), this cluster definition is conservative as it treats all possible clusters as true ones. Therefore this approach has the maximal possible sensitivity in detecting outbreaks outside the SHCS. Moreover, our findings remained robust under alternative cluster definitions (combinations of bootstrap support values (70%, 95%) and genetic distances (1.5% and 4.5%). The non-SHCS clusters found were comparable to those found under the presented cluster definition. The SHCS IQR and maximum cluster size remained stable at all combinations strict and liberal, reflecting the robustness of those clusters. Thus despite the lack of a consensus for cluster definitions in molecular epidemiology20,21,22, our findings are robust in this regard.

We also presented a sequence-based method for inferring demographics information for patients with no such data available. This method allowed for the characterization of the demographics of non-SHCS patients and, more generally, proves to be a potential method for extending the coverage of other cohorts by using sequence data from non-cohort individuals (especially given the ever increasing ubiquity of sequencing data). It should be noted that the general problems associated with imputation (see for example23) also apply here. As with all inference methods, the quality of the training set plays a vital role in the prediction performance. In our data, some of the patients had uncertainties about the route of infection HET or IDU (7% of the all patients). This was in return reflected in the predictor performance where MSM membership was better predicted than HET and IDU. In addition, there are limitations to the correspondence of the HIV phylogenetic tree and the true underlying structure of the transmission chain, which might affect the prediction performance21,24. Despite the imperfect performance of the predictor, and given the difficulties associated with evaluating multinomial classification25, the predictor still provides some information about an otherwise completely unlit part of the population. Finally, the imperfect performance of the predictor does not affect the other major results of our analysis (overrepresentation of non-B subtypes among non-cohort patients; no large outbreaks completely outside the cohort). Therefore this method could allow the identification of sub-populations who are underrepresented in cohorts and who may therefore profit from additional recruitment and care efforts.

More generally, this work highlights the utility of molecular epidemiology in extending and testing the scope of classical epidemiological data. As sequencing pathogens from a large and representative number of patient samples becomes increasingly affordable, the situation we have encountered with the SHCS and the Swiss HIV epidemic will become more frequent: such a situation is characterized by high-quality and detailed epidemiological data available for a limited number of patients and sequence data available beyond this group. Our work further demonstrates that in this setting sequence data can be used to approximate some of the missing epidemiological information, to assess how well the available epidemiological data captures the spread of an infectious disease (in particular to test whether a cohort misses entire outbreaks), and to identify marginalized subpopulations.

Methods

Ethics statement

Participants in the SHCS provided written informed consent and the SHCS, this study, all associated experimental and non-experimental protocols has been approved and is in accordance with local ethics committees’ guidelines in the respective study centres (Kantonale Ethik-Kommission Zurich, Basel, Bern, Lugano, St Gallen, Geneva and Lausanne). In addition, the Kantonale Ethik-Kommission Zurich approved of the present analysis (approval number 29/14).

Patients data

The SHCS-drug-resistance database is part of the SHCS, which is a national cohort study that started in 1988 with ongoing enrolment and semi-annual follow up visits3. The SHCS-drug-resistance database contains 21,623 sequences (July 2014) belonging to 11,127 patients. Genotypic resistance tests are done routinely when the patient is first diagnosed, upon a viral-load test, or if virus rebound is observed during ART; in addition retrospective sequencing from the SHCS bio-bank was performed to maximize representativeness. Only the earliest sequence of every SHCS patient was included in the phylogenetic tree, and only from patients belonging to MSM, HET, and IDU transmission groups (covering 96% of HIV cases in the SHCS). Further information about the sequences and their availability can be found in the supplementary material.

The BSV database started collecting genotypic resistance tests in 2003 as they became part of the standard of care in Switzerland; the analysis was hence restricted to data collected after 2003 from the SHCS as well. As some non-cohort patients choose to partake in the SHCS after having been tested and deposited in the BSV-database, suspected duplicate records between non-SHCS and the SHCS were discarded. A non-SHCS sequence was suspected to be part of the SHCS (and hence discarded) if it matched an SHCS patient record on sex and birthdate, and their sequences formed a monophyletic clade.

It is plausible that the same non-SHCS patient might have several sequences in the BSV database, therefore, in order to keep only the single earliest sequence per non-SHCS patient, we assumed that two sequences with the same sex and birthdate and a genetic distance of <2% belonged to the same patient. We choose this conservative cut-off based on Hightower et al.26 finding that the genetic diversity of HIV pol gene sequence in patients followed longitudinally for a median of 1.8 years was less than 1%, and the median time for SHCS patients between the last negative HIV test and registration being 3.1 years. Technically, a graph was created for every group of sequences sharing the same sex and birthdate with edge-lengths being the genetic distance between two sequences. Edges were dissolved if they carried a genetic distance >2% (indicating that the two vertices/sequences were likely not from the same patient). Isolated vertices were considered unique patients while only the sequence with the earliest sampling date was retained from the connected vertices in the graph.

Phylogenetic tree construction

To identify transmission clusters, we first pooled the Swiss sequences with non-Swiss sequences from the Los-Alamos sequence database27. Specifically, we considered all non-Swiss sequences available in the Los-Alamos sequence database which spanned the protease and reverse transcriptase genes. Of those, only a single sequence per patient was kept provided that the sequence spanned at least 850 nucleotides of the protease and reverse transcriptase (positions 2253–3870 of the HXB2 reference sequence, 114,609 sequences (April/2014)). After excluding Swiss sequences present in the Los Alamos Database, for every Swiss sequence, the ten closest sequences were retrieved using BLAST (Standalone 2.2.28+28). Overall, 27,803 foreign sequences were pooled with the Swiss sequences for the final phylogenetic tree construction.

Next, the Stanford and International Antiviral Society-USA drug resistance mutations lists were consulted and the major drug resistance mutations were removed29,30 to avoid the potentially distorting effect of ART-driven convergent evolution.

Sequences were aligned to HXB2 using Muscle (V3.731, default settings) respectively and the phylogenetic tree was constructed using FastTree 2.132 with the Generalized time-reversible model and the CAT approximation (which has been shown to be better or as accurate as other maximum-likelihood phylogenetic inference methods33). Bootstrap-support values for clusters were derived from 100 bootstrap trees (using FastTree 2.132 and GNU Parallel34).

Clusters extraction and demographics prediction

Clusters were defined as monophyletic sub-trees with at least 80% Swiss sequences (SHCS and non-SHCS)12. In addition, sensitivity analysis was performed with other cluster definitions (combinations of bootstrap support values (70%, 95%) and inter-cluster genetic distances (1.5 and 4.5%)). Clusters were extracted (using Ape35, Caper36, R37) so that every Swiss sequence could maximally be present once: if a sequence was part of two clusters one of which is nested within the other, only the larger cluster was kept.

For the SHCS sequences, the patients’ demographics were available in the SHCS-database. For Swiss non-SHCS patients, sex and birthdate were provided with the sequences in the BSV-database, other demographic variables (transmission group, ethnicity) were inferred using phylogenetic proximity. Starting from a given non-SHCS tip the tree was traversed up to the parent node then down to the nearest (based on cophenetic distance) SHCS child node with known demographics. If no child node with known demographic were to be found from this node, then the tree was climbed up to the following parent, and the previous process repeated recursively until an SHCS patient with known demographics is found (R code present with supplementary materials). This method was validated on two sets. The first consisted of randomly chosen SHCS patients matching the number of non-SHCS patients (2,875 and for whom demographics was known) with 10-folds cross validation. For the second test set, we approximated the non-SHCS populations by choosing SHCS patients who were found to be HIV-positive at least three years prior to enrolment in the SHCS; those patients were termed “late-enrollers”. As this group also experienced barriers to enrolment in the SHCS, it represents a better approximation for the non-cohort population.

These analyses were performed using uni- and multivariable logistic regression adjusting for the following potential confounders: sex, sample year, subtype, and transmission group.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Shilaih, M. et al. Genotypic Resistance Tests Sequences Reveal the Role of Marginalized Populations in HIV-1 Transmission in Switzerland. Sci. Rep. 6, 27580; doi: 10.1038/srep27580 (2016).

References

Magnani, R., Sabin, K., Saidel, T. & Heckathorn, D. Review of sampling hard-to-reach and hidden populations for HIV surveillance. AIDS 19 Suppl 2, S67–72 (2005).

Raboud, J. et al. Representativeness of an HIV cohort of the sites from which it is recruiting: results from the Ontario HIV Treatment Network (OHTN) cohort study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13, 31 (2013).

Schoeni-Affolter, F. et al. Cohort profile: the Swiss HIV Cohort study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 39, 1179–89 (2010).

Thierfelder, C. et al. Participation, characteristics and retention rates of HIV-positive immigrants in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. HIV Med. 13, 118–26 (2012).

Burns, F. M., Fakoya, A. O., Copas, A. J. & French, P. D. Africans in London continue to present with advanced HIV disease in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 15, 2453–5 (2001).

del Amo, J., Erwin, J., Fenton, K. & Gray, K. AIDS and mobility: looking to the future. Migration and HIV/AIDS in Europe – recent developments and needs for future action (2001). Available at http://www.popline.org/node/239456 Accessed on 17th of February 2016.

Girardi, E., Sabin, C. A. & Monforte, A. dArminio. Late Diagnosis of HIV Infection: Epidemiological Features, Consequences and Strategies to Encourage Earlier Testing. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 46, S3–S8 (2007).

Gardner, E. M., McLees, M. P., Steiner, J. F., Del Rio, C. & Burman, W. J. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52, 793–800 (2011).

United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). The Gap Report (2014). Available at http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2014/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf Accessed on 17th of February 2016.

Grenfell, B. T. et al. Unifying the epidemiological and evolutionary dynamics of pathogens. Science 303, 327–32 (2004).

Volz, E. M., Koelle, K. & Bedford, T. Viral phylodynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 9, e1002947 (2013).

Kouyos, R. D. et al. Molecular epidemiology reveals long-term changes in HIV type 1 subtype B transmission in Switzerland. J. Infect. Dis. 201, 1488–97 (2010).

Paraskevis, D. et al. Tracing the HIV-1 subtype B mobility in Europe: a phylogeographic approach. Retrovirology 6, 49 (2009).

Hemelaar, J., Gouws, E., Ghys, P. D. & Osmanov, S. Global trends in molecular epidemiology of HIV-1 during 2000–2007. AIDS 25, 679–89 (2011).

Kouyos, R. D. et al. Molecular epidemiology reveals long-term changes in HIV type 1 subtype B transmission in Switzerland. J. Infect. Dis. 201, 1488–97 (2010).

Taylor, B. S., Sobieszczyk, M. E., McCutchan, F. E. & Hammer, S. M. The challenge of HIV-1 subtype diversity. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 1590–602 (2008).

Drescher, S. M. et al. Treatment-naive individuals are the major source of transmitted HIV-1 drug resistance in men who have sex with men in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 58, 285–94 (2014).

Hachfeld, A. et al. Reasons for late presentation to HIV care in Switzerland. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 18, 20317 (2015).

Frost, S. D. W. et al. Eight challenges in phylodynamic inference. Epidemics 10, 88–92 (2015).

Dennis, A. M. et al. Phylogenetic studies of transmission dynamics in generalized HIV epidemics: an essential tool where the burden is greatest? J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 67, 181–95 (2014).

Grabowski, M. K. & Redd, A. D. Molecular tools for studying HIV transmission in sexual networks. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 9, 126–33 (2014).

Marzel, A. et al. HIV-1 Transmission During Recent Infection and During Treatment Interruptions as Major Drivers of New Infections in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Clin. Infect. Dis, doi: 10.1093/cid/civ732 (2015).

Sterne, J. A. C. et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ 338, b2393 (2009).

Resik, S. et al. Limitations to contact tracing and phylogenetic analysis in establishing HIV type 1 transmission networks in Cuba. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 23, 347–56 (2007).

Sokolova, M. & Lapalme, G. A systematic analysis of performance measures for classification tasks. Inf. Process. Manag. 45, 427–437 (2009).

Hightower, G. K. et al. HIV-1 clade B pol evolution following primary infection. PLoS One 8, e68188 (2013).

Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos National Laboratory HIV Sequence database. Available at http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/ Accessed on 17th of February 2016.

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 421 (2009).

Johnson, V. A. et al. Update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1: March 2013. Top. Antivir. Med. 21, 6–14

Bennett, D. E. et al. Drug resistance mutations for surveillance of transmitted HIV-1 drug-resistance: 2009 update. PLoS One 4, e4724 (2009).

Edgar, R. C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–7 (2004).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. FastTree 2–approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS One 5, e9490 (2010).

Liu, K., Linder, C. R. & Warnow, T. RAxML and FastTree: comparing two methods for large-scale maximum likelihood phylogeny estimation. PLoS One 6, e27731 (2011).

Tange, O. GNU Parallel: The Command-Line Power Tool USENIX. The USENIX Magazine 42–47 (2011). Available at https://www.usenix.org/publications/login/february-2011-volume-36-number-1/gnu-parallel-command-line-power-tool Accessed on 17th of February 2016.

Paradis, E., Claude, J. & Strimmer, K. APE: Analyses of Phylogenetics and Evolution in R language. Bioinformatics 20, 289–290 (2004).

Orme, D. et al. caper: Comparative Analyses of Phylogenetics and Evolution in R (2013). Available at http://star-www.st-andrews.ac.uk/cran/web/packages/caper/vignettes/caper.pdf Accessed on 17th of February 2016.

R Core Team (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available at http://www.R-project.org/ Accessed on 17th of February 2016.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients who participate in the SHCS; the physicians and study nurses for excellent patient care; the resistance laboratories for high-quality genotypic drug-resistance testing; SmartGene, Zug, Switzerland, for technical support; Brigitte Remy, Martin Rickenbach, F. Schoeni-Affolter, and Yannick Vallet from the SHCS Data Center in Lausanne for data management; and Danièle Perraudin and Mirjam Minichiello for administrative assistance. This study has been financed in the framework of the Swiss HIV Cohort Study, supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF grant #33CS30-134277) and the SHCS projects #470, 528, 569, 683, the SHCS Research Foundation, the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant #24730–112594 and -130865 (to HFG), the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (grant FP7/2007–2013), under the Collaborative HIV and Anti-HIV Drug Resistance Network (CHAIN; grant 223131, to HFG), and by a further research grant of the Union Bank of Switzerland, in the name of an anonymous donor to HFG, an unrestricted research grant from Gilead, Switzerland to the SHCS research foundation, and by the University of Zurich’s Clinical research Priority Program (CRPP) “Viral infectious diseases: Zurich Primary HIV Infection Study” (to HFG). R. Kouyos was supported by # PZ00P3-142411 and BSSGI0_155851. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: R.D.K., H.F.G. and M.S. Performed the experiments: M.S. Analyzed the data: M.S. and R.D.K. Contributed data/reagents/materials/analysis tools: A.M., W.L.Y., A.U.S., J.S., J.B., S.Y., T.K., V.A., M.C., H.H.H., P.L.V., E.B., H.F. and the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Wrote the paper: M.S. and R.D.K. All authors have seen and reviewed the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

H.F.G. has been an adviser and/or consultant for the following companies: GlaxoSmithKline, Abbott, Gilead, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Tibotec, Pfizer and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and has received unrestricted research and educational grants from Roche, Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Astra-Zeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck Sharp & Dohme (all money went to institution). RDK received travel grants from Gilead.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Shilaih, M., Marzel, A., Yang, W. et al. Genotypic Resistance Tests Sequences Reveal the Role of Marginalized Populations in HIV-1 Transmission in Switzerland. Sci Rep 6, 27580 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27580

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27580

This article is cited by

-

Data linkage to evaluate the long-term risk of HIV infection in individuals seeking post-exposure prophylaxis

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Parent-offspring regression to estimate the heritability of an HIV-1 trait in a realistic setup

Retrovirology (2017)

-

Using nearly full-genome HIV sequence data improves phylogeny reconstruction in a simulated epidemic

Scientific Reports (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.