Abstract

A compilation of U-Pb age, geochemical and isotopic data for granitoid plutons in the southern Central Asian Orogenic Belt (CAOB), enables evaluation of the interaction between magmatism and orogenesis in the context of Paleo-Asian oceanic closure and continental amalgamation. These constraints, in conjunction with other geological evidence, indicate that following consumption of the ocean, collision-related calc-alkaline granitoid and mafic magmatism occurred from 255 ± 2 Ma to 251 ± 2 Ma along the Solonker-Xar Moron suture zone. The linear or belt distribution of end-Permian magmatism is interpreted to have taken place in a setting of final orogenic contraction and weak crustal thickening, probably as a result of slab break-off. Crustal anatexis slightly post-dated the early phase of collision, producing adakite-like granitoids with some S-type granites during the Early-Middle Triassic (ca. 251–245 Ma). Between 235 and 220 Ma, the local tectonic regime switched from compression to extension, most likely caused by regional lithospheric extension and orogenic collapse. Collision-related magmatism from the southern CAOB is thus a prime example of the minor, yet tell-tale linking of magmatism with orogenic contraction and collision in an archipelago-type accretionary orogen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Evolution of continental crust is typically marked by a diverse range of magmatism in different tectonic settings1. As the final magmatic products of crustal differentiation, granitoids constitute an essential component in the generation of continental crust on Earth2. Extraction of granite from the middle-lower crust and its emplacement at shallower levels, is the principal mechanism by which continental crust has become differentiated1. A major setting for granite genesis is in accretionary orogens developed at plate boundaries through subduction processes as a result of transitory coupling across the plate boundary3. Post-subduction/accretionary contraction (continent/arc–continent collision) commonly results in disappearance of ocean basins and subsequent shortening and thickening of the crust2,3, which enables granite extraction, ascent and emplacement1. Thus knowledge of the origin and petrogenesis of granitoids in response to final orogenic contraction in accretionary orogens is essential to understanding material recycling and magmatic processes along convergent margins.

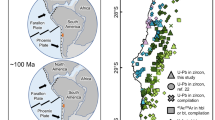

The Central Asian Orogenic Belt (CAOB, Fig. 1a), is widely recognized for its accretionary tectonics and production of massive amounts of juvenile crust in the Phanerozoic, especially in the Paleozoic4,5,6,7. It formed by long-lived subduction-accretionary processes from the Mesoproterozoic to the Permian, driven by the evolution and closure of the Paleo-Asian Ocean4,5,6,7. Based on distinct geochemical characteristics, the CAOB has been termed an “internal” orogen in contrast to the circum-Pacific “external” orogens8. It has also been referred to as a non-collisional orogen, contrasting with the archetypical Alpine-Himalayan collisional orogen3. However, all accretionary orogens are ultimately involved in a collisional phase at the end of an orogenic cycle due to ocean closure and termination of subduction and this may lead to subsequent shortening and thickening of the continental crust3. Therefore, collision-related magmatism marks the final episode of a Wilson Cycle and documents the transition from a convergent plate boundary to intraplate evolution9.

Simplified tectonic map of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt (CAOB) and study region.

(a) Simplified geological sketch map of the CAOB showing the main tectonic sub-divisions5. The location of (b) is indicated. (b) Simplified tectonic map of the southeastern CAOB showing the main tectonic sub-divisions and the location of Fig. 2 6,12. Light grey zone represents the northern early-middle Paleozoic continental block and the Hutag Uul Block10,12 or northern accretionary orogen (NAO)6, whereas the dark grey zone represents the southern early-middle Paleozoic continental block10,12 or southern accretionary orogen (SAO)6. Published zircon U-Pb ages for early Permian-Triassic magmatic rocks in the region are from refs 12,15, 16, 17,32 and 55. This figure is generated using CorelDRAW X5 (version 15.1.0.588) created by the 2010 Corel Corporation (http://www.corel.com/cn/) and the map will not have a copyright dispute.

The early-middle Paleozoic oceanic subduction/arc magmatism in the southern CAOB has been well documented10,11. But the time of switching from arc-related magmatism to post-accretionary magmatism is still actively debated. In particular, there is an ongoing controversy with respect to the Permian to Triassic tectonic setting6,12,13. In order to evaluate these changes, we selected the Xilinhot area of Inner Mongolia, China, which consists of, from north to south, the northern accretionary orogen (NAO), the Solonker-Xar Moron (SXM) suture zone and the southern accretionary orogen (SAO)6,10,13 (Fig. 1b). A series of linear or belt granodioritic plutons are present in this area and we selected four of these for SHRIMP U-Pb dating in order to testing they were coeval and perhaps related to the final episode of magmatism associated to closure of the Paleo-Asian Ocean and amalgamation of the southern CAOB. Our study indicates that geochronological, geochemical and isotopic characteristics of these end-Permian granitoid plutons along the Solonker-Xar Moron suture zone are indeed correlated with the final amalgamation of the CAOB (Figs 1b and 2). Together with other recently-published data from plutonic and volcanic rocks in adjacent areas, we examine the changes in these geochemical parameters in the late Permian-Triassic magmatic rocks and discuss the interplay between magmatism and orogenesis in the context of closure of the Paleo-Asian Ocean and final continental amalgamation/collision of the South Mongolia Terranes (SMT) with the North China Craton (NCC) to form the largest and most complex Phanerozoic accretionary orogenic belt on Earth.

Distribution map of granitoids in the Xilinhot area of Inner Mongolia, China.

The NE-trending Carboniferous-Permian granitoid belt and the location of the studied Beikeli, Baiyinwendu, Sumutai and Salihade plutons are shown. Published zircon U-Pb ages for granitoids in the region are from refs 15,31 and 32. This figure is generated using CorelDRAW X5 (version 15.1.0.588) created by the 2010 Corel Corporation (http://www.corel.com/cn/) and the map will not have a copyright dispute.

Results

Zircon U-Pb ages

Zircon U-Pb dating by SHRIMP (see Supplementary Dataset 1) yielded weighted mean 206Pb/238U ages of 255 ± 2 Ma (Beikeli pluton), with one young and discordant 206Pb/238U age of 241 ± 4 Ma rejected as an outlier; 251 ± 2 Ma (Baiyinwendu pluton) and 252 ± 2 Ma (Sumutai pluton), both devoid of any zircon inheritance; and 253 ± 4 Ma (Salihada pluton), with one 289 ± 4 Ma inherited zircon grain (Figs 2 and 3). Emplacement of these plutons therefore took place at the end-Permian (255–251 Ma).

Cathodoluminescence (CL) images of selected zircon grains and U-Pb concordia diagrams.

(a) Granodiorite (XL922-2) from the Beikeli pluton, (b) Granodiorite (XL921-14) from the Baiyinwendu pluton, (c) Granodiorite (XL920-8) from the Sumutai pluton and (d) Granodiorite (11SH-5) from the Salihada pluton. Zircon U-Pb ages (red circles), εHf(t) values (yellow circles) and δ18O values (black circles).

Whole rock major and trace elements and Sr-Nd isotopes

The granitoids from the four plutons show a similar range in SiO2 (65.3–71.3 wt. %), K2O (1.7–2.6 wt. %), Na2O (4.5–5.0 wt. %) and CaO (2.4–3.4 wt. %) contents, which indicate calc-alkalic characteristics (Fig. 4a, see Supplementary Dataset 2). The granitoids also have similar contents of Fe2O3T (1.9–3.4 wt. %) and MgO (0.7–1.7 wt. %), with all samples plotting in the magnesian field (Fig. 4b). The ASI values of all samples range from 1.20 to 1.35, indicating most are weakly peraluminous (Fig. 4c).

Selected major element diagrams for the Beikeli, Baiyinwendu, Sumutai and Salihada plutons.

(a) Na2O + K2O - CaO vs. SiO2 diagram56, (b) TFeO/(TFeO + MgO) vs. SiO2 diagram56 and (c) ASI vs. SiO2 diagram56. TFeO = FeO + 0.9 Fe2O3, ASI = molecular Al/(Ca − 1.67P + Na + K). Data for the early Permian arc granitoids and Early-Middle Triassic adakitic granitoids are from refs 15,19 and 23.

All samples exhibit LREE-enriched patterns in the chondrite-normalized rare earth element diagram (Fig. 5a). They show relatively weak REE fractionation ((La/Yb)N = 3.46–9.80)). Most samples show weak negative Eu anomalies (Eu/Eu* = 0.54–0.96) (Fig. 5a), although one sample from the Beikeli pluton (XL922-7.1) and another from the Baiyinwendu pluton (XL921-17) have positive Eu anomalies (Eu/Eu* = 1.26–1.36). The granitoids have low Ni (mostly <10 ppm) and Cr (mostly <35 ppm) contents. In the primitive mantle-normalized spidergram (Fig. 5b), all samples show positive Rb, Th, K and LREE anomalies and negative Ba, Ta, Nb, P and Ti anomalies (Fig. 5b).

(a) Chondrite-normalized rare earth element patterns and (b) Primitive mantle-normalized trace element spider diagrams. The values of chondrite and primitive mantle are from Sun and McDonough57. Data for the early Permian arc granitoids and Early-Middle Triassic adakitic granitoids are same as in Figure 4.

Samples from the four plutons have similar whole-rock Nd-Sr isotopic compositions and record radiogenic Sri values of 0.7023–0.7037 and positive εNd(t) values (+2.6 to +3.9) (Fig. 6, see Supplementary Dataset 3), with Neoproterozoic Nd model ages of 0.72–1.10 Ga.

(a) εNd(t) value vs. Sri value diagram and (b) whole-rock εNd(t) vs. zircon εHf(t) diagram. Data for the Early-Middle Triassic adakitic granitoids, early Permian arc granitoids and early Permian bimodal volcanic rocks in the area are from refs 15,16, 17, 18,19 and 23. The terrestrial array is from Vervoort and Blichert-Toft58.

Zircon Hf-O isotopes

All zircon grains from these samples have positive εHf(t) values of +8.3 to +14.5 (Figs 6b and 7, see Supplementary Dataset 4) and young two-stage Hf model ages (TDM2) of 0.36–0.75 Ga. Samples from the four plutons have variable δ18O values of 5.02 to 7.58% (Fig. 8a,b). Of which, the Salihada grantioids record δ18O values of 5.85–7.58%, which are higher than those of the other three plutons (Fig. 8a), indicating more recycled supercrustal components were involved.

(a) zircon δ18O vs. Zircon εHf(t) diagram and (b) zircon δ18O vs. whole-rock εNd(t) diagram. The early Permian arc granitoid field is from Li et al.15.

Discussion

Episodes of collision-related magmatic activity

The southern CAOB has been regarded as a complex tectonic collage of island arcs, accretionary complexes, micro-continental blocks and fragments of oceanic crust that were amalgamated together during the closure of the Paleo-Asian Ocean between the active margin of the South Mongolia Terranes to the north and the northern margin of the North China Craton to the south6,10,11,12. Prior to final amalgamation and collision, Late Carboniferous to early Permian (324–272 Ma) arc-signature granitoids and coeval mafic arc complexes with bimodal volcanic rocks formed in the NAO12,14,15,16 (Figs 1b and 2). The latest early Permian (277–273 Ma) arc-related granitoids occur as stocks along the southern margin of the NAO that were considered to be derived from an already hybrid andesitic magma in an Andean-type active continental margin6,15. To the north, an early Permian (292–275 Ma) belt of alkaline granites occurs along the China-Mongolia border17 (Fig. 1b). To the south, the Solonker-Xar Moron suture zone is 2500 km long and 50–100 km wide and includes early Permian (299–280) ophiolite complexes, which were stitched together by collision-related igneous rocks (255–248 Ma)12, recording final closure of the Paleo-Asian Ocean. A short magmatic hiatus (ca. 270 Ma to 259 Ma) was the result of initial collision15. Therefore, four major magmatic episodes along the SXM suture zone can be proposed in response to final amalgamation of the CAOB: subduction controlled (300–273 Ma)6,12,15, slab break-off (255–250 Ma)12, intracontinental contraction (251–235 Ma)13,18 and post-orogenic extension (230–200 Ma)13,14,18.

The precise zircon U-Pb ages of 255 ± 2 Ma to 251 ± 2 Ma in this study for the four granodioritic plutons (Fig. 3) establish the end-Permian age of granitoids immediately to north of the suture zone. The end-Permian to Triassic was a critical period in the evolution of the CAOB that was punctuated by two major episodes of magmatic activity (255–235 Ma and 230–200 Ma)18. Magmatic rocks of the earlier episode are mainly I-type granodiorites (this study) with some S-type granites19, adakitic andesite and adakitic granitoids12,20, sanukitoid-like high-Mg diorite12 and E-MORB-like dolerite12, which are mainly distributed along the SXM suture zone (Fig. 9). Most show negligible to weak negative Eu anomalies and negative anomalies of Nb and Ta18. Magmatic activity associated with the younger episode was sparse, although it has been reported sporadically in the Sonid Zuoqi region21, related to Indosinian extension22. The rocks are classified as high-K granitoids (222–204 Ma) of A-type affinity with strong negative Eu anomalies. More extensive Late Triassic magmatic activity occurred to the east of the Songliao Basin in Northeast China14.

Geochemical and isotopic constraints on petrogenesis of collision-related magmatic rocks

The end-Permian (255–251 Ma) granitoids record uniform SiO2, K2O, Na2O and CaO contents, have low MgO and Fe2O3T contents, moderate to weak negative Eu anomalies and low abundances of Ni and Cr, indicating a crustal origin (Fig. 4). They are magnesian granitoids that contain hornblende and have a weak peraluminous nature, characteristic features of I-type granites, although they are generally distinct from the early Permian arc granitoids15 (Fig. 4). They also show different REE and trace element patterns from the early Permian arc granitoids, which have higher REE contents and elevated negative Eu and Sr anomalies (Fig. 5). The negative Ta and Nb anomalies of the end-Permian granitoids (Fig. 5b) are a common feature of continental crust produced by geochemical differentiation of arc-derived magmas and their weakly negative Eu anomalies indicate only minor plagioclase fractionation (Fig. 5a). However, Early-Middle Triassic adakitic granitoids along the suture zone show stronger REE fractionation and lower HREEs18,19, probably implying residual garnet in the source.

The end-Permian granitoids also have low Sri values (0.7023–0.7037), positive εNd(t) values (+2.6 to +3.9) (Fig. 6), with Neoproterozoic Nd model ages of 0.72–1.10 Ga, suggesting a predominantly juvenile crustal source. Furthermore, these end-Permian granitoids record positive zircon εHf(t) values of +8.3 to +14.5 (Figs 6b and 7) and young two-stage Hf model ages (TDM2) of 0.36–0.75 Ga, supporting a juvenile crustal source. However, their εNd(t) values and zircon εHf(t) values are slightly higher than those of the early Permian arc granitoids in the area15, but significantly higher than those of Early-Middle Triassic granitoids18,19,23,24 (Figs 6b and 7), indicating greater involvement of young crustal components in their generation. Petrological characteristics and geochemical and isotopic data suggest that those early Permian arc granitoids were mainly derived from juvenile mantle-derived magma mixed with supracrustal materials that had been metasomatically modified by melts/fluids released from the subducting oceanic slab15. In addition, the relative enrichment in Sr–Nd–Hf isotopic compositions for the Early-Middle Triassic adakitic granitoids along the SXM suture zone indicate that they likely contained some old continental components, possibly derived from the North China Craton18,19,23,24.

Three end-Permian plutons show mantle-like to slightly higher δ18O values of 5.02 to 6.52%, which are similar to many of those Early-Middle Triassic adakitic granitoids along the SXM suture zone (Fig. 8), suggesting minor involvement of supracrustal materials. However, the end-Permian Salihada grantioids have high δ18O values of 5.85–7.58% that are similar to the early Permian arc granitoids (Fig. 8), indicating a greater involvement of supracrustal materials. The isotopic characteristics of these end-Permian granitoids imply a juvenile crustal origin with minor recycled supercrustal materials (sedimentary rocks).

The zircon saturation temperature (TZr) from whole-rock compositions (major element and Zr concentration)25 calculated for the end-Permian granitoids yield values of 695–805 °C, with an average of 736 °C. The temperature is distinctly lower than that of the early Permian arc-related granitoids (800–930 °C)15, indicating a colder heating mantle by the end of the Permian. However, their low temperature (<800 °C) is similar to that of postcollisional Early-Middle Triassic adakitic granitoids (av. 747 °C) with high Sr/Y ratios (>20) but low Cr (<40 ppm) and MgO, indicating an origin probably from hydrous partial melting of thickened lower crust26. The episode of the linear magmatism along the SXM suture zone thus was responsible for orogenic final contraction and collision of the CAOB18. As indicated by the whole-rock Nd and zircon Hf isotopic compositions of the end-Permian granitoids (Figs 6 and 7), the participation of juvenile mafic magma in the formation of these granitoids was significant. The detachment of the Paleo-Asian oceanic slab and asthenospheric upwelling through the slab window following the cessation of subduction would therefore trigger partial melting of mafic lower crust to generate these calc-alkaline granitoids. In summary, we suggest that the onset of post-collisional magmatism as a result of slab break-off and asthenospheric upwelling occurred at the end-Permian (See the following discussion).

A tectono-magmatic scenario of terminal accretion and crustal growth

The four granodioritic plutons examined in this study were emplaced at the end-Permian (between 255–251 Ma) immediately to the north of the SXM suture zone and coincident with mafic complex (255–248 Ma)12 in the Solonker area and coeval or slightly postdating adakitic granitoids (251–245 Ma)18,19 along the SXM suture zone, indicating that a narrow linear (~1000 km) magmatic “flare-up” along the suture zone occurred at around 250 ± 5 Ma.

Considering that there has been no arc-related magmatism or marine sedimentation along the suture zone since the late Permian12,13, a subduction-related setting can be ruled out. Furthermore, lithospheric delamination generally results in voluminous magmatism rather than limited linear magmatism, so this too appears unlikely. When the South Mongolia Terranes and the North China Craton collided in the middle-late Permian6,12, the tensile stresses between the buoyant continental lithosphere and previously-subducted oceanic lithosphere likely led to the separation and detachment of the subducted oceanic slab27,28,29 and slab detachment will result in a narrow, linear zone of magmatism with a limited spatial distribution. Although it remains difficult to explore the geodynamic mechanism responsible for generation of the linear magmatic belt along the SXM suture zone because of the general lack of exposure, the comparable tectonomagmatic events lead us to argue that slab break-off at ca. 255 Ma, soon after a weak arc–continent collision, was a plausible mechanism. Slab break-off records to start with a narrow slab window between the continent and the subducted oceanic slab, resulting in a linear magmatic belt27. Such a linear end-Permian magmatic belt, including E-MORB-like dolerite, adakitic andesite, sanukitoid anorthosite, mafic volcanic rocks and I-type granitoids, was distributed along the SXM suture zone (Fig. 9). Jian et al.12 also proposed that the latest Permian (255–250 Ma) igneous rocks in the Mandula mélange along the SXM suture zone were derived from decompression melting of upwelling asthenosphere from a slab window. The upwelling of asthenosphere during slab break-off can trigger the formation of a variety of magmas, especially tholeiitic basaltic magma27,28. For example, low-K tholeiitic basalts along the SXM suture zone, that were generated by decompression melting of the asthenosphere, have been identified in the Xilinhot and Linxi areas (ca. 236–252 Ma)30, consistent with the slab break-off model. Therefore, a slab break-off model can account for this linear “flare-up” event during the latest Permian to early Triassic along the Solonker-Xar Moron suture zone.

This study focussed in the southern CAOB has wider implications for post-accretionary processes. The end-Permian granitoids along the SXM suture zone show positive εNd(t) values (+2.6 to +3.9) and positive zircon εHf(t) values (+8.3 to +14.5), recording significant juvenile crustal input by vertical addition of juvenile magma, with only minor crustal recycling (most δ18O values = 5.02 to 6.52%) after closure of the Paleo-Asian Ocean. Our study of the end-Permian granitoids from the southern CAOB thus provides a snapshot of post-accretionary vertical crustal growth in response to final slab break-off.

Linking magmatism with orogenic processes and tectonic evolution

In the early Paleozoic, rocks within the CAOB were generated by the subduction and accretion within the Paleo-Asian Ocean6,7,11, resulting in the formation of the SAO and NAO along the ocean margins, while they were still separated by the Paleo-Asian Ocean6,10,12. During the Carboniferous to early Permian, tectonic activity continued with subduction and arc formation along the Solonker-Xar Moron belt (Fig. 10a)6,12,15. Meanwhile, the outboard migration of arc-related magmas in the NAO was probably responsible for slab retreat and roll-back15. Slab roll-back during the early Permian has been interpreted to occur before final closure of the Paleo-Asian Ocean15, which induced upper plate (South Mongolia Terranes) extension, causing arc splitting, exhumation of microcontinent slivers (e.g., Xinlin Gol complex) and backarc basins and marginal continental rifting, with calc-alkaline arc15,31, A-type32, alkaline33 and bimodal magmatism16,33 (Figs 9 and 10a). The progressive consolidation of the accreted terranes (mostly early Paleozoic) enabled an Andean-type margin to develop on northern side of the SXM suture zone during the Permian6. Coeval with this southward subduction of the Paleo-Asian Ocean beneath the North China Craton a mafic forearc complex formed along the future SXM suture zone12, accompanied by Andean-type arc magmatism along the northern margin of the NCC34 (Figs 9 and 10a).

Finally, the Paleo–Asian Ocean closed by double-sided subduction in the late Permian, leading to formation of the SXM suture zone6,12,15,19,34. The available palaeomagnetic data also indicate that the North China Craton and South Mongolia Terranes were very close in the early Permian35. Also, a short magmatic hiatus (ca. 270–259 Ma) occurred, during which time a remnant sea with distal marine sedimentation was present along the SXM suture zone13,15 (Figs 9 and 10b).

This remnant sea likely closed in the Early Triassic, due to contraction between the North China Craton and South Mongolia Terranes, resulting in intermediate P/T greenschist-blueschist facies metamorphism and syn-collisional S-type granites along the SXM suture zone13,19,36 (Figs 9 and 10c). The northern margin of the NCC was also reactivated in the end-Permian to Early Triassic. During this period, the northern margin of the NCC experienced collision-related magmatism, N–S compression, regional exhumation and uplift of Precambrian crystalline basement, including the formation of E–W-trending south-verging folds and south-verging ductile shear zones37. Intense late Permian–Early Triassic shortening along the northern margin of the NCC developed as a result of the collision and contraction of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt38,39. Therefore, a tectonic switch from early Permian subduction and extension to late Permian contraction along the SXM suture zone was marked by slab break-off at ca. 255–250 Ma (Figs 9 and 10c). The end-Permian to Early Triassic magmatism along the SXM suture zone, likely resulted from partial melting of the mafic lower crust, which was triggered by asthenospheric upwelling through the slab window during the collision-induced break-off of the Paleo-Asian oceanic slab (Figs 9 and 10c). The inferred slab break-off thus marked the end of Paleo-Asian oceanic subduction and termination of the accretionary orogenesis.

Subsequent crustal shortening and thickening, similar in some extent to that of Southern Tibet40, is consistent with voluminous Early Triassic sediments being generated from the uplifted orogen in the Linxi area13 and formation of lower crust-derived adakite, S-type granite and high-Mg andesite below thickened (>40 km) crust18,19,20 (Figs 9 and 10d). The thickening was focused along the thermally-softened remnant basin, where middle-late Permian sediments were deposited, therefore a shorted-lived (ca. 255–240 Ma) narrow orogen likely formed along what was to become the SXM suture zone and was squeezed between the older northern accretionary and southern accretionary orogens (Figs 9 and 10d). The stacking of the accretionary wedge above the subduction zone induced the initial slow thickening following slab break-off in the end-Permian, with subsequent faster thickening along the SXM suture zone in the Early Triassic (Fig. 10c,d). Available geological and geophysical evidence suggest that extension of the crust started in the Late Triassic, accompanied by the emplacement of A-type granitic rocks14, strike-slip faulting41 and formation of metamorphic core complexes22. At this time regional lithospheric extension affected the whole of NE China42 (Figs 9 and 10e).

Methods

Whole-rock geochemical analyses

The samples were crushed after removal of weathered surfaces. The small rock chips were then pulverized into powder using an agate mortar to a grain size of <200 mesh. Whole-rock geochemical analyses were performed at the Analytical Laboratory, Beijing Research Institute of Uranium Geology, China. Major elements were analyzed by X-ray fluorescence spectrometry with a Phillips PW 2404 system. Ferrous iron was determined by the wet chemical titration method. Trace elements (including REE) were determined by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). The analytical uncertainties for major element are generally within 1–5%. In-run analytical precision for most trace elements is better than 5%.

Whole-rock Sr-Nd analyses

The Sr-Nd isotopic compositions were measured by thermal ionization mass spectrometry (TIMS) using a Finnigan MAT-261 mass spectrometer at the Analytical Laboratory, Beijing Research Institute of Uranium Geology, China. The detailed chemical separation and isotopic measurement procedures are described in Wu et al.43. The 87Sr/86Sr ratios were normalized to 86Sr/88Sr = 0.1194 and 143Nd/144Nd ratios to 146Nd/144Nd = 0.7219. Total procedural blanks were <300 pg for Sr and <100 pg for Nd and the estimated analytical uncertainties of 147Sm/144Nd and 87Rb/86Sr ratios were <0.5%. The Sr standard solution (NBS 987) was analyzed and yielded 87Sr/86Sr ratio of 0.710250 ± 14 (2σ), whereas the Nd standard solution (SHINESTU) yielded a ratio of 0.512113 ± 6 (2σ) during data acquisition.

Zircon U-Pb analyses

Zircon grains were extracted by heavy liquid and magnetic techniques and further purified by hand-picking under a binocular microscope. They were set in an epoxy mount which was ground and polished to section the zircons in half. Cathodoluminescence (CL) images were taken using a scanning electron microscope at the Beijing SHRIMP Center, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, in order to identify any internal structures and to ensure a selection of good analytical sites.

Zircon U-Pb isotope analyses were obtained using the sensitive high resolution ion microprobe (SHRIMP II) at the John de Laeter Centre for Mass Spectrometry, Curtin University, Australia under standard operating conditions (six-scan cycles, 2 nA primary O2-beam, mass resolution c.a. 5000), following analytical procedures described by Williams44. Inter-element fractionation in the ion emission of zircon was corrected using reference standard TEM2 (416.8 Ma)45. Corrections of Pb/U ratios were made by normalization to zircon standard M257 (206Pb/238Pb = 0.09100, corresponding to an age of 561.3 Ma)46. The data were corrected for common lead using the measured 204Pb. U-Pb isotope data were calculated and plotted using the SQUID and ISOPLOT software of Ludwig47,48. The analytical data are presented with 1σ error boxes on the concordia plots and uncertainties in weighted mean ages are quoted at the 95% confidence level (2σ).

Zircon oxygen isotopic analyses

Zircon oxygen isotopes were measured using the Cameca IMS 1280 at the Centre for Microscopy, Characterisation and Analysis, the University of Western Australia in Perth and the analytical procedures are similar to those reported by Li et al.49. The oxygen analysis spots were placed on or adjacent to the SHRIMP pits on the same zircon within a domain of uniform CL. The Cs+ primary ion beam was accelerated at 10 kV, with an intensity of 2–3 nA and a spot diameter of about 20 μm. A normal-incidence electron flood gun was used to compensate for sample charging during analysis, with an homogeneous electron density over a 100 μm oval area. Negative secondary ions were extracted with a −10 kV potential. The field aperture was set to 4000 μm and the transfer-optics magnification was 130. The energy slit width was 30 eV, with a 5 eV gap. The entrance slit width was ca. 110 μm and exit slit width for multi-collector Farady cups (FCs) for 16O and 18O was 500 μm (MRP = ca. 2200). The intensity of 16O− was typically 2 × 109 cps. Oxygen isotopes were measured in multi-collector mode using two off-axis Faraday cups. The Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) probe was used for magnetic field control stability.

One analysis took ∼4 min consisting of pre-sputtering (∼10 s), automatic beam centering (∼60 s) and integration of oxygen isotopes intensities (20 cycles ×4 s, total 80 s). Uncertainties on individual analyses are reported at the 2σ level and include propagation of uncertainties associated with calculation of instrumental mass fractionation, drift correction and calculation of δ values relative to Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (V-SMOW). The internal precision of a single analysis was generally better than 0.15% for the 18O/16O ratio. External precision was <0.20% for bracketing standards for all reported analyses. The 18O/16O ratios are reported in delta notation as δ18O values by normalizing to V-SMOW (18O/16O)V-SMOW = 0.0020052. The internal standard used for correction of mass fractionation was Temora 2 zircon with a δ18O value of 8.2 ± 0.01% (1SD)45,46,47,48,49,50.

Zircon hafnium isotopic analyses

Zircon Hf isotope analyses were carried out using a Newwave UP213 laser-ablation microprobe, attached to a Neptune multi-collector ICP-MS at the Institute of Mineral Resources, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing. Instrumental conditions and data acquisition were as described by Wu et al.51. The Hf analyses were made on the same spots as the previous oxygen isotope analyses, with a 50 μm spot size. Helium was used as the carrier gas to transport the ablated sample from the laser-ablation cell to the ICP-MS torch and was mixed with argon. In order to correct for isobaric interferences of 176Lu and 176Yb on 176Hf, 176Lu/175Lu = 0.02658 and 176Yb/173Yb = 0.796218 ratios were applied52. For instrumental mass bias correction, Yb isotope ratios were normalized to 172Yb/173Yb = 1.3527452 and Hf isotope ratios to 179Hf/177Hf = 0.7325 using an exponential law. The mass bias behavior of Lu was assumed to follow that of Yb and mass bias correction protocols were as described by Wu et al.43,51. Zircons GJ1 and Plesovice were used as the reference standards during routine analyses, with weighted mean 176Hf/177Hf ratios of 0.282007 ± 0.000007 (2σ, n = 36) and 0.282476 ± 0.000004 (2σ, n = 27), respectively. These are indistinguishable from the 176Hf/177Hf ratios of 0.282000 ± 0.000005 (2σ) and 0.282482 ± 0.000008 (2σ), respectively, determined using the solution analysis method by Morel et al.53 and Sláma et al.54.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Li, S. et al. Linking magmatism with collision in an accretionary orogen. Sci. Rep. 6, 25751; doi: 10.1038/srep25751 (2016).

References

Brown, M. Granite: From genesis to emplacement. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 125, 1079–1113 (2013).

Condie, K. C., Belousova, E., Griffin, W. L. & Sircombe, K. N. Granitoid events in space and time: Constraints from igneous and detrital zircon age spectra. Gondwana Res. 15, 228–242 (2009).

Cawood, P. A. et al. Accretionary orogens through Earth history. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Pub. 318, 1–36 (2009).

Şengör, A. M. C., Natal’in, B. A. & Burtman, V. S. Evolution of the Altaid tectonic collage and Palaeozoic crustal growth in Eurasia. Nature 364, 299–307 (1993).

Jahn, B. M., Wu, F. Y. & Chen, B. Granitoids of the Central Asian orogenic belt and continental growth in the Phanerozoic. T. Roy. Soc. Edin-Earth 91, 181–193 (2000).

Xiao, W. J. et al. A Tale of Amalgamation of Three Permo-Triassic Collage Systems in Central Asia: Oroclines, Sutures and Terminal Accretion. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 43, 477–507 (2015).

Windley, B. F., Alexeiev, D., Xiao, W., Kröner, A. & Badarch, G. Tectonic models for accretion of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. J. Geol. Soc. London 164, 31–47 (2007).

Collins, W. J., Belousova, E. A., Kemp, A. I. S. & Murphy, J. B. Two contrasting Phanerozoic orogenic systems revealed by hafnium isotope data. Nature Geosci. 4, 333–337 (2011).

Burke, K. Plate Tectonics, the Wilson Cycle and Mantle Plumes: Geodynamics from the Top. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 39, 1–29 (2011).

Jian, P. et al. Time scale of an early to mid-Paleozoic orogenic cycle of the long-lived Central Asian Orogenic Belt, Inner Mongolia of China: Implications for continental growth. Lithos 101, 233–259 (2008).

Xu, B., Charvet, J., Chen, Y., Zhao, P. & Shi, G. Z. Middle Paleozoic convergent orogenic belts in western Inner Mongolia (China): framework, kinematics, geochronology and implications for tectonic evolution of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Gondwana Res. 23, 1342–1364 (2013).

Jian, P. et al. Evolution of a Permian intraoceanic arc–trench system in the Solonker suture zone, Central Asian Orogenic Belt, China and Mongolia. Lithos 118, 169–190 (2010).

Li, S. et al. Triassic sedimentation and postaccretionary crustal evolution along the Solonker suture zone in Inner Mongolia, China. Tectonics 33, 2013TC003444 (2014).

Wu, F. Y. et al. Geochronology of the Phanerozoic granitoids in northeastern China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 41, 1–30 (2011).

Li, S., Wilde, S. A., Wang, T., Xiao, W. J. & Guo, Q. Q. Latest Early Permian granitic magmatism in southern Inner Mongolia, China: Implications for the tectonic evolution of the southeastern Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Gondwana Res. 29, 168–180 (2016).

Zhang, X. H., Zhang, H. F., Tang, Y. J., Wilde, S. A. & Hu, Z. C. Geochemistry of Permian bimodal volcanic rocks from central Inner Mongolia, North China: Implication for tectonic setting and Phanerozoic continental growth in Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Chem. Geol. 249, 262–281 (2008).

Tong, Y. et al. Permian alkaline granites in the Erenhot–Hegenshan belt, northern Inner Mongolia, China: Model of generation, time of emplacement and regional tectonic significance. J. Asian Earth Sci. 97, Part B, 320–336 (2015).

Li, S., Wang, T., Wilde, S. A. & Tong, Y. Evolution, source and tectonic significance of Early Mesozoic granitoid magmatism in the Central Asian Orogenic Belt (central segment). Earth-Sci. Rev. 126, 206–234 (2013).

Li, J. Y., Gao, L. M., Sun, G. H., Li, Y. P. & Wang, Y. B. Shuangjingzi middle Triassic syn-collisional crust-derived granite in the east Inner Mongolia and its constraint on the timing of collision between Siberian and Sino-Korean paleo-plates. Acta Geol. Sin. 23, 565–582 (in Chinese with English abstract) (2007).

Liu, Y. S. et al. Triassic high-Mg adakitic andesites from Linxi, Inner Mongolia: Insights into the fate of the Paleo-Asian ocean crust and fossil slab-derived melt–peridotite interaction. Chem. Geol. 328, 89–108 (2012).

Shi, Y. R. et al. SHRIMP Dating of Diorites and Granites in Southern Suzuoqi, Inner Mongolia. Acta Geol. Sin. 78, 789–799 (in Chinese with English abstract) (2004).

Davis, G. A., Xu, B., Zheng, Y. & Zhang, W. Indosinian extension in the Solonker suture zone: The Sonid Zuoqi metamorphic core complex, Inner Mongolia, China. Front Earth Sci. 11, 135–143 (2004).

Liu, W., Siebel, W., Li, X. J. & Pan, X. F. Petrogenesis of the Linxi granitoids, northern Inner Mongolia of China: constraints on basaltic underplating. Chem. Geol. 219, 5–35 (2005).

Liu, W., Pan, X. F., Liu, D. Y. & Chen, Z. Y. Three-step continental-crust growth from subduction accretion and underplating, through intermediary differentiation, to granitoid production. Int. J. Earth Sci. 98, 1413–1439 (2009).

Miller, C. F., McDowell, S. M. & Mapes, R. W. Hot and cold granites? Implications of zircon saturation temperatures and preservation of inheritance. Geology 31, 529–532 (2003).

Lu, Y. J., Loucks, R. R., Fiorentini, M. L., Yang, Z. M. & Hou, Z. Q. Fluid flux melting generated postcollisional high Sr/Y copper ore–forming water-rich magmas in Tibet. Geology 43, 583–586 (2015).

Davies, J. H. & von Blanckenburg, F. Slab breakoff: A model of lithosphere detachment and its test in the magmatism and deformation of collisional orogens. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 129, 85–102 (1995).

von Blanckenburg, F. & Davies, J. H. Slab breakoff: A model for syncollisional magmatism and tectonics in the Alps. Tectonics 14, 120–131 (1995).

van Hunen, J. & Allen, M. B. Continental collision and slab break-off: A comparison of 3-D numerical models with observations. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 302, 27–37 (2011).

Zhang, L. C. et al. Age and tectonic setting of Triassic basic volcanic rocks in southern Da Hinggan Range. Acta Petrol. Sin. 24, 911–920 (in Chinese with English abstract) (2008).

Li, Y. L. et al. Early Paleozoic to Middle Triassic bivergent accretion in the Central Asian Orogenic Belt: insights from zircon U-Pb dating of ductile shear zones in central Inner Mongolia, China. Lithos 205, 84–111 (2014).

Shi, G. H. et al. Emplacement age and tectonic implications of the Xilinhot A-type granite in Inner Mongolia, China. Chinese Sci. Bull. 49, 723–729 (2004).

Yarmolyuk, V. V., Kuzmin, M. I. & Ernst, R. E. Intraplate geodynamics and magmatism in the evolution of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. J. Asian Earth Sci. 93, 158–179 (2014).

Zhang, S. H. et al. Contrasting Late Carboniferous and Late Permian-Middle Triassic intrusive suites from the northern margin of the North China craton: Geochronology, petrogenesis and tectonic implications. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 121, 181–200 (2009).

Zhang, S. H. et al. Crustal structures revealed from a deep seismic reflection profile across the Solonker suture zone of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt, northern China: An integrated interpretation. Tectonophysics 612–613, 26–39 (2014).

Zhang, J., Wei, C. & Chu, H. Blueschist metamorphism and its tectonic implication of Late Paleozoic–Early Mesozoic metabasites in the mélange zones, central Inner Mongolia, China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 97, Part B, 352–364 (2015).

Wang, Y., Zhou, L. & Zhao, L. Cratonic reactivation and orogeny: An example from the northern margin of the North China Craton. Gondwana Res. 24, 1203–1222 (2013).

Lin, S. Z., Zhu, G., Yan, L. J., Song, L. H. & Liu, B. Structural and chronological constraints on a Late Paleozoic shortening event in the Yanshan Tectonic Belt. Chinese Sci. Bull. 58, 3922–3936 (2013).

Wang, Z. H. & Wan, J. L. Collision-Induced Late Permian–Early Triassic Transpressional Deformation in the Yanshan Tectonic Belt, North China. J. Geol. 122, 705–716 (2014).

Chung, S.-L. et al. The nature and timing of crustal thickening in Southern Tibet: Geochemical and zircon Hf isotopic constraints from postcollisional adakites. Tectonophysics 477, 36–48 (2009).

Zhao, P., Faure, M., Chen, Y., Shi, G. & Xu, B. A new Triassic shortening-extrusion tectonic model for Central-Eastern Asia: Structural, geochronological and paleomagnetic investigations in the Xilamulun Fault (North China). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 426, 46–57 (2015).

Wang, T. et al. Pattern and kinematic polarity of late Mesozoic extension in continental NE Asia: Perspectives from metamorphic core complexes. Tectonics 30, TC6007 (2011).

Wu, F. Y., Yang, J. H., Wilde, S. A. & Zhang, X. O. Geochronology, petrogenesis and tectonic implications of Jurassic granites in the Liaodong Peninsula, NE China. Chem. Geol. 221, 127–156 (2005).

Williams, I. S. U-Th-Pb geochronology by ion microprobe. Rev. Econ. Geol. 7, 1–35 (1998).

Black, L. P. et al. Improved 206Pb/238U microprobe geochronology by the monitoring of a trace-element-related matrix effect; SHRIMP, ID–TIMS, ELA–ICP–MS and oxygen isotope documentation for a series of zircon standards. Chem. Geol. 205, 115–140 (2004).

Nasdala, L. et al. Zircon M257 - a Homogeneous Natural Reference Material for the Ion Microprobe U-Pb Analysis of Zircon. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 32, 247–265 (2008).

Ludwig, K. R. Squid 1.02: a user’s manual. Berkeley Geochronological Centre Special Publication No 2 (2001).

Ludwig, K. R. ISOPLOT 3.0: A Geochronological Toolkit for Microsoft Excel. Special publication No. 4. Berkeley Geochronology Center (2003).

Li, X. H. et al. Petrogenesis and tectonic significance of the ~850 Ma Gangbian alkaline complex in South China: Evidence from in situ zircon U–Pb dating, Hf–O isotopes and whole-rock geochemistry. Lithos 114, 1–15 (2010).

Valley, J. W. Oxygen Isotopes in Zircon. Rev. Mineral Geochem. 53, 343–385 (2003).

Wu, F. Y., Yang, Y. H., Xie, L. W., Yang, J. H. & Xu, P. Hf isotopic compositions of the standard zircons and baddeleyites used in U-Pb geochronology. Chem. Geol. 234, 105–126 (2006).

Chu, N. C. et al. Hf isotope ratio analysis using multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry: an evaluation of isobaric interference corrections. J. Anal. Atom. Spectrom. 17, 1567–1574 (2002).

Morel, M. L. A., Nebel, O., Nebel-Jacobsen, Y. J., Miller, J. S. & Vroon, P. Z. Hafnium isotope characterization of the GJ-1 zircon reference material by solution and laser ablation MC-ICPMS. Chem. Geol. 255, 231–235 (2008).

Sláma, J. et al. Plešovice zircon—A new natural reference material for U–Pb and Hf isotopic microanalysis. Chem. Geol. 249, 1–35 (2008).

Zhang, X. H., Yuan, L., Xue, F., Yan, X. & Mao, Q. Early Permian A-type granites from central Inner Mongolia, North China: Magmatic tracer of post-collisional tectonics and oceanic crustal recycling. Gondwana Res. 28, 311–327 (2015).

Frost, B. R. & Frost, C. D. A Geochemical Classification for Feldspathic Igneous Rocks. J. Petrology 49, 1955–1969 (2008).

Sun, S. S. & McDonough, W. F. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts; implications for mantle composition and processes. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Pub. 42, 313–345 (1989).

Vervoort, J. D. & Blichert-Toft, J. Evolution of the depleted mantle: Hf isotope evidence from juvenile rocks through time. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac. 63, 533–556 (1999).

Liu, J. et al. A late-Carboniferous to early early-Permian subduction–accretion complex in Daqing pasture, southeastern Inner Mongolia: Evidence of northward subduction beneath the Siberian paleoplate southern margin. Lithos 177, 285–296 (2013).

Acknowledgements

Comments from editor Peter A. Cawood, the anonymous reviewers and Dr. Xuan-Ce Wang are gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by the Major State Basic Research Program of China (Grant No. 2013CB429803), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 41402194, 41302177, 41390441 and 41230207), projects of the China Geological Survey (Grant Nos 12120113013700, 12120113013800 and 12120113094000) and a project of the China Postdoctoral Foundation (2015T81073). It is a contribution to IGCP 592.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. had the idea for the study, wrote the manuscript, helped perform the chemical and isotopic analyses and formulated the conclusions. S.-L.C., S.A.W., T.W. and W.-J.X. evaluated the results and conclusions and assisted with manuscript preparation and writing. Q.-Q.G. performed the trace element and Sr-Nd isotopic analyses.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Chung, SL., Wilde, S. et al. Linking magmatism with collision in an accretionary orogen. Sci Rep 6, 25751 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25751

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25751

This article is cited by

-

Petrogenesis of late Permian–middle Triassic volcanic rocks in the Linxi area, southeastern Inner Mongolia, China: implication for late-stage tectonic evolution of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt

International Journal of Earth Sciences (2023)

-

Recycling of supra-crustal materials in the rhyolites from north Sonid Youqi: implications for the crustal evolution in the southeast Central Asian Orogenic Belt

International Journal of Earth Sciences (2022)

-

Permian-Triassic magmatic evolution of granitoids from the southeastern Central Asian Orogenic Belt: Implications for accretion leading to collision

Science China Earth Sciences (2021)

-

Early-Middle Triassic Intrusions in Western Inner Mongolia, China: Implications for the Final Orogenic Evolution in Southwestern Xing-Meng Orogenic Belt

Journal of Earth Science (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.