Abstract

The green alga Scenedesmus obliquus can form inducible defensive morphs under grazing threat. Costs and trade-offs of inducible defense are expected to accompany the benefits of defensive morphs, but are hard to detect under nutrient-sufficient experimental conditions. To test the existence of costs associated with inducible defense, we cultured S. obliquus along resource availability gradients in the presence or absence of infochemical cues from Daphnia, and measured the strength of defensive colony formation and fitness characters. Under the lowest phosphorous concentration, the expression of inducible defensive colony resulted in decreased growth rate, which provides direct evidence for physiological costs. Along the gradient reduction of phosphorous concentration or light intensity, inducible defense in S. obliquus showed a decreasing trend. However, the photosynthetic efficiency of S. obliquus was barely affected by its defense responses, suggesting that the negative correlations between resource availability and colony formation of this alga may be due to resource-based trade-offs in the allocation of limited resources. Thus, our results indicated that expression of inducible defense of S. obliquus was impaired under insufficient phosphorus or light. Furthermore, under severe phosphate deficiency, obvious physiological costs of inducible defense could be detected even though defensive colony formation also decreased significantly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phytoplankters, which supply a major part of primary productivity in waters, play an important role in aquatic ecosystems. However, several processes, e.g., hydromechanical dispersion, sedimentation, and consumption by grazers, may cause major loss of phytoplankton biomass. Phytoplankters have to avoid sinking out of euphotic zones to maintain access to sufficient light. Therefore, large size may be resisted among phytoplankton to reduce settling velocity1. In addition, small algal cells have larger surface-to-volume ratio and shorter internal transport distance. Thus, maintaining a relatively small size will be favored by algae to assimilate inorganic nutrients from the aquatic environment2.

Since phytoplankters share an apparently refugeless openwater habitat with zooplankton and phytoplanktivorous fish, consumption by herbivores is another major factor contributing to phytoplankton loss. To avoid being grazed, many taxa of algae in euphotic water have evolved various chemical or physical defensive strategies, such as toxin production, spine or colony formation, and silica plates3,4,5, which allow them to survive in the same area with grazers. Algae’s resistance to herbivores can be either constitutive or inducible. Inducible defenses allow phytoplankton to resist the risk of being grazed under the threat of predation and save extra energy to maintain the defense systems in the absence of predators. The genus Scenedesmus, which forms defensive colonies under predation pressure, is one of the genera that can form induced defensive phenotypes in freshwater5,6. Scenedesmus commonly reproduces asexually through the formation of autospores, in which the mother cell divides into 2–16 daughter cells7. Daughter cells subsequently form a new overlapping or staggered colony and then break through the parental cell wall, or fail to join and then leave the parental cell wall separately8,9. The infochemicals released by zooplanktons such as Daphnia and Brachionus during active grazing processes may trigger the formation of colonies instead of unicells to resist mortality from grazers6,10. The formation of colony as an anti-herbivore strategy relying on grazing infochemicals is familiar in aquatic ecosystems. Besides Scenedesmus, many species can respond to infochemicals released by herbivores feeding on focal algal species, e.g. Microcystis11, Coelastrum12. A bloom species Phaeocystis, which is abundant in the ocean, can form colonies in response to non-species-specific grazing chemical cues4,13.

In terms of energy requirements, defenses that are induced only in the presence of herbivores are considered more efficient than constitutive defenses under variable grazing risk14. The adaptive benefits of colony formation for Scenedesmus spp. have been investigated in many studies15,16. However, no direct evidence about the cost accompanying with the benefit is detected. Trade-offs and costs associated with grazer-induced colony formation exist theoretically; otherwise, this defensive phenotype would be fixed17. Since the energy storage of organisms is limited, excessive investment of energy for defense against grazers would impose restriction on growth and maintenance. For Scenedesmus, two main potential indirect costs coupled with morphological defense are identified: reduction of surface-to-volume ratios and enhancement of sinking risk18. Both costs would result in loss of competitive advantage in phytoplankton populations. As four, eight, or even more algal cells join together to form a larger resistant coenobium, volume is increased compared to single algal cells, but a high surface-to-volume ratio is sacrificed. In addition, overlapping or staggered coenobiums may result in “package effect” on inner cells, and light capture and nutrient assimilation may be negatively influenced19.

Apart from the relatively small surface area for nutrient and light absorption, increased sedimentation rate of large defensive coenobiums also have negative effect on the population of Scenedesmus. Colonies not only settle faster but are also less able to resuspend to upper water compared to unicells. For non-motile phytoplankters, prolonged residence in warm upper water with sufficient illumination is a primary requirement. Higher risk of sinking out of euphotic zone increases the loss of population biomass, and decreases the growth rate for light limitation18,20. Aside from grazing, sedimentation loss appears to be a major threat to small phytoplankton in the pelagic zone21. Thus, to preserve high biomass, a trade-off in production of stable large colony may be required to avoid the selective pressure of predation and division into single cells to maximize nutrient uptake in Scenedesmus.

Recent research has tried to reveal the cost associated with induced colony formation in Scenedesmus18,22,23. However, the direct fitness costs of forming defensive colonies in terms of growth or other physiological indexes18,24 has been difficult to determine, which may be due to the abundance of nutrients in culture medium used in those studies. Because of the package effect19, colonies should have less chlorophyll-specific absorption coefficients than unicells, which should be reflected in the growth rate. However, no significant decrease is observed in growth rate18. Forming defensive morphs tends to improve the adaptive fitness of Scenedesmus. Nevertheless, when alga is cultured in poor conditions, such as nutritional deficiency or light insufficiency, such conditions may be disadvantageous if the cost of maintaining colonies is high. Colony formation of S. acutus has been reported to be a constitutive defense response under phosphorus-sufficient conditions, but an inducible defense response under P-limited conditions22, indicating the existence of trade-off between colony formation and nutrient availability. As previous studies have showed, maintaining defensive morphs impairs the competitive ability of Scenedesmus under nutrient-limited conditions caused by competition23,25. Therefore, we hypothesized that when resource is insufficient, the cost of induced defense may be obvious, and a trade-off between defense and resource absorption may emerge. To examine our hypothesis, we measured the induced colony formation, population growth, and photosynthesis of Scenedesmus under different phosphorus concentrations and light intensities.

Results

Inducible defense of Scenedesmus under different phosphorus concentrations

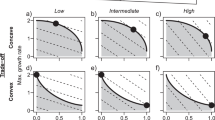

Addition of Daphnia filtrate stimulated the increase of colony size under all five P concentrations (Fig. 1). In the absence of Daphnia filtrate, no difference was detected in cells per particle among different P concentrations (F = 1.172, p = 0.331). A three-way ANOVA indicated that the induced colony formation was significantly decreased by decrease in P concentration (Table 1). Under the exposure of Daphnia infochemicals, the colony size of S. obliquus increased dramatically and peaked on day 4 (Fig. 1). Fitted curves revealed that the value of Cmax declined, which was caused by decreased P concentration. To investigate the relationship of colony size with resource availability, the observed Cmax from each triplicate of the Daphnia filtrate treatments was fitted against P concentrations or light intensities (Fig. 2). The dots of Cmax-observed were the actual maximums. The Cmax-observed in response to P concentration followed a rectangular hyperbolic model and increased with increasing P concentration, but it no longer increased when the P concentration was above 0.5 mg L−1 (Fig. 2a).

The growth capacity of S. obliquus declined with decreased P concentration (Fig. 3). Addition of Daphnia filtrate led to significant decline in growth rate in the lowest P concentration (F = 9.188, p = 0.039). In other P concentrations, no statistically significant decrease was observed between control and Daphnia filtrate groups. A two-way ANOVA was conducted to test the effect of Daphnia filtrate and P concentration on growth rate. The result indicated that both factors had significant influences on the growth rate, but no interaction was detected between the two factors (Table 2).

Vertical lines represent ±1 SE (n = 3). Different capital letters above solid bars denote significant (P < 0.05) differences among the control groups, while different lowercase letters above hollow bars denote significant (P < 0.05) differences among Daphnia filtrate groups. The asterisk above a short horizontal line indicates significant difference (P < 0.05) between control and Daphnia filtrate groups under certain P concentrations.

The photosynthetic efficiency of S. obliquus was affected by different P concentrations with or without Daphnia filtrate. The maximal efficiency of PSII photochemistry (Fv/Fm) of S. obliquus was not significantly different between the control and Daphnia filtrate groups (F = 0.0117, p = 0.914). A three-way ANOVA revealed significant positive effects of time (F = 5.475, p = 0.002) and P concentration on Fv/Fm (F = 7.115, p < 0.001). Consistent with the ratio of Fv/Fm, Daphnia filtrate had no significant influence (F = 0.756, p = 0.387) on the effective quantum yield of PSII (ΦPSII), but ΦPSII varied significantly with both time (F = 7.283, p < 0.001) and P concentration (F = 6.648, p < 0.001). In the two low P concentration treatments (0.05 and 0.2 mg L−1), ΦPSII decreased from day 5. ETRmax showed an increase on day 3. No significant variation was observed between control and Daphnia filtrate groups. Significant effects of time (F = 39.447, p < 0.001) and P concentration (F = 10.452, p < 0.001), as well as significant interactions between the two factors (F = 2.758, p = 0.001), were observed.

Inducible defense of Scenedesmus under different light intensities

Similar to the effect of P concentration on inducible defense of S. obliquus, light intensity had significant influence on colony formation (Table 1). The number of cells per particle was fitted by Gaussian distribution under five light intensities. An increasing trend of the inducible defensive colony formation was observed with increased illumination (Fig. 4). Unlike the hyperbolic relationship between Cmax-observed and P concentration, Cmax-observed in response to light intensity matched the linear models (Fig. 2b). One-way ANOVA on Cmax indicated significant light intensity effect (F = 22.928, p < 0.001). Cmax of S. obliquus at 9 μmol photons m−2s−1 was less than half of Cmax at 72 μmol photons m−2s−1. However, no significant difference of Cmax was observed under the light intensities within the range of 18–54 μmol photons m−2 s−1. The decreased growth rate of S. obliquus at 9 μmol photons m−2 s−1 indicated growth inhibition by low light intensity (Fig. 5). Results of two-way ANOVA showed that different light intensities significantly affected the growth rate of S. obliquus, but the addition of Daphnia filtrate had no significant influence (Table 2). The growth rate of S. obliquus under the highest P concentration in the different P gradient experiment (at the light level of 45 μmol photons m−2 s−1) was lower than that in the light intensity experiment. This was possibly due to the higher initial cell density in the P gradient experiment, and the decrease in intracellular phosphorus quota because of pre-treatment of algal cells in non-phosphorus medium.

The photosynthetic efficiency of S. obliquus changed with light intensity with or without Daphnia filtrate. Three-way ANOVA indicated that the ratio of Fv/Fm was influenced significantly by time (F = 4.261, p = 0.008) and light intensity (F = 5.017, p = 0.001). The ratio of Fv/Fm increased with increase in light intensity. At the highest light intensity, the initial Fv/Fm was high, but decreased with cultural time. Moreover, a time × light intensity interaction (F = 1.946, p = 0.041) was found. No significant Daphnia filtrate effect was detected (F = 0.702, p = 0.405). The three factors all affected the ΦPSII of S. obliquus significantly (contrast by a three-way ANOVA, time: F = 13.029, p < 0.001; light intensity: F = 3.927, p = 0.006; Daphnia filtrate: F = 4.609, p = 0.035). ΦPSII was negatively affected by the presence of Daphnia filtrate—it decreased significantly on day 3 at 9 μmol photons m−2 s−1, and on day 5 and 7 at 54 and 72 μmol photons m−2 s−1. Significant time × light intensity (F = 10.408, p < 0.001) and light × Daphnia filtrate (F = 4.132, p = 0.009) interactions were also observed. For ETRmax, significant time (F = 13.057, p < 0.001) and light intensity (F = 7.042, p < 0.001) effects and time × light intensity interaction (F = 2.414, p = 0.010) were detected. The effect of Daphnia filtrate on ETRmax was not statistically significant (F = 3.123, p = 0.081).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the grazer-induced morphological defense of S. obliquus and the effect of resource gradient on this defense response. At all phosphorus concentrations and light intensity treatments, Daphnia filtrate induced the defensive colony formation of by S. obliquus. Consistent with previous studies18,26, the numbers of cells per particle increased under the exposure of Daphnia filtrate and then decreased, possibly because of the increase of cell densities and the degradation of chemical cues. Colony formation in response to Daphnia infochemicals exhibited a decreasing trend with decreasing environmental resource availability (Fig. 2). A strong two-way interaction between resource availability (phosphorous concentration or light intensity) and Daphnia filtrate indicated that the character of phenotypic plasticity of S. obliquus was determined by the complex interactive effects of biotic and abiotic factors, which is consistent with previous studies. Alteration of anti-predation response depending on environmental resource availability has also been observed in many other species of photoautotrophs27,28,29 and preys at higher trophic levels30,31.

The formation of defensive colony is highly effective for withstanding grazing pressure and preserving biomass10,32. However, limitations and costs should be expected, otherwise colony formation will be a constitutive defense33. To avoid excess costs of defense, many organisms adjust the intensity of inducible defenses based on predation risk and conspecific density30,34,35, indicating trade-offs between the benefits and costs of inducible defense. The “plant defense hypotheses”36 posits that decline of defensive colony formation along the resource availability gradient. In the present study, the decrease in growth rate under low resource availability condition indicates that inducible defense is accompanied by some limitations and costs.

Both light limitation and phosphate deficiency impaired the grazing-induced defense in S. obliquus. The negative correlations between resource availability and colony formation in S. obliquus may be due to resource-based trade-offs in the allocation of limiting resources. It has been already known that extracellular polysaccharides play an important role in increasing the stickiness of algal cells to form coenobia and to aggregate together. Biosynthesis of polysaccharides requires more energy and carbohydrate allocation. Therefore, increasing the production of extracellular polysaccharides will require extra investment from the intracellular pools of carbon. Limitation of external Pi (inorganic phosphate) will reduce the intracellular concentrations of Pi and ATP synthesis37. For PSII, the electron flow and carbon fixation rate in the algae exhibit linear correlation38, and the decrease of PSII electron transport rate will inhibit the biosynthesis of polysaccharides. Deficiency of external inorganic phosphate supply affects the photosynthetic apparatus of phytoplankton39 because a part of the light energy is allocated for nutrient uptake instead of carbon fixation40. With Pi deficiency, photosynthesis is inhibited because of decreased ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate pool size41, and chlorophyll content is also lower42, thereby causing decreased carbon assimilation area in algal cells. In the present study, P-limitation had a significant negative effect on the ratio of Fv/Fm and value of ΦPSII, probably suggesting stress on PSII reaction centers under low P concentrations. ETRmax was also decreased under low P concentrations, suggesting that efficiency of the electron transport chain was affected. Although no significant Daphnia filtrate effect was observed on photosynthetic parameters, growth reduction emerged under phosphorous deficiency, specifically under the lowest P concentration, which is a relatively low level in eutrophic lakes43. Growth inhibition of induced algae was possibly due to increased requirement of extracellular polysaccharides to form defensive colonies under phosphate deficiency, suggesting the direct costs associated with inducible defense of S. obliquus.

The influence of light intensity on the defensive colony formation of S. obliquus was similar to that of phosphorous concentration gradient. In this study, the inducible colony formation decreased significantly at a light intensity of 9 μmol photons m−2 s−1 (Fig. 4), indicating that the ability of S. obliquus to form defensive colonies was inhibited under light limitation, which may be due to decreased production of carbohydrate when light intensity is low44. Biomass growth, carbon fixation rate, and carbohydrate productivity of phytoplankton increase with increasing light intensity below the light saturation point45. Under low light intensity, algal cells accumulate more lipid than carbohydrates, whereas high light intensity causes carbohydrate accumulation and cellular lipid content decreases46. As the key factor of photosynthesis, light has a major influence on photosynthetic carbon fixation, energy synthesis, and nutrient consumption rate47. The observed decrease in ΦPSII affected by Daphnia filtrate indicated the potential package effect of forming colonies. ETRmax was notably low under the lowest light intensity, which indicated strong inhibition of electron transport efficiency. Biomass production was reduced due to decrease of photosynthetic efficiency, and no efficient energy or carbohydrate source was available to maintain biomass growth for defensive colony formation. Therefore according to our study, despite the high selection pressure of herbivores, deficiency of resource availability is likely to be the limitation for S. obliquus in forming defensive colonies, and trade-offs between defense and development will occur. Furthermore, the reduction of photosynthetic efficiency of S. obliquus under low resource conditions may limit energy allocation for defense.

However, contradictory evidence on the trade-offs of resource allocation between growth, reproduction, and defense has been reported28,48,49,50,51,52,53. The resource availability hypothesis predicts that large investment on anti-herbivore defenses is favorable when resources are limited48,49. However, the carbon–nutrient balance hypothesis assumes resource allocation between production of defensive compounds and plant growth50. The variations of allocation costs associated with inducible defense may depend on the kind of deficient resources28,51, type of defense (different defensive mechanisms may have different potential sources of costs52), and biosynthesis of defensive compounds53. Considering the defensive mechanism of S. obliquus, poor availability of phosphorous and light will have negative effect on colony production. Colony formation in S. obliquus induced by FFD-6, a type of anionic surfactant, also decreases in nutrient-limited cultures54. Unlike S. obliquus, S. acutus produces colonies constitutively when phosphorous is sufficient despite Daphnia cues, but only produces colonies after perceiving Daphnia cues when phosphorus is limited22, indicating that the cost of forming colonies may be high and that nutrient availability does affect colony formation. Although allocation of limited resources (phosphorus and light) to growth and reproduction instead of resistance would be favored by S. obliquus in order to avoid physiological cost, maintenance of defensive colony under phosphorus deficiency decreased S. obliquus growth. Growth reduction was also detected in Phaeocystis globosa which formed grazer-induced colonies in low nutrient conditions, indicating the existence of costs29.

Despite the internal physiological costs of forming anti-grazing morphs of S. obliquus, previous studies also indicated the existence of other costs23,25. Maintenance of colonies reduces the ability to compete for resources and habitats with competitors23. Our previous study also showed that the co-existence of competitors impairs the inducible defense in S. obliquus25. Thus, these experimental studies have demonstrated the opportunity costs of defense. However, under natural conditions with complex abiotic and biotic interactions, potential ecological costs may also occur. Ecological costs are indirect consequences of induced defense and are difficult to test under laboratory conditions. Research has begun to detect the ecological costs of plants and animals (e.g., delayed flowering55, attracting additional natural enemies56, trade-offs between resistance and tolerance57, and other kinds of ecological costs). For phytoplankton, forming large-sized colonies is an efficient morphological defense against small herbivores. However, this defensive morph will be less effective when encountering grazers with large gape size15. The enhanced sinking rate of colonial S. obliquus will be disadvantageous for the alga to remain suspended in upper warm and euphotic waters10.

In conclusion, the expression of inducible defensive colony in S. obliquus shows dynamic responses on the availability of main environmental resources (phosphate and light). Resource insufficiency limits the expression of inducible defensive colony formation, thereby suggesting the existence of trade-offs of intercellular resource allocation between defense and growth. Our observation of growth inhibition of defensive algae under low phosphorus condition suggests that the costs may be detected under specific conditions, such as nutrient deficiency. Studying the costs accompanying the benefits of inducible defense is highly important for understanding the mechanism and evolution of inducible defense. Our work provides evidence supporting the existence of costs and trade-offs of inducible defense in S. obliquus.

Methods and Materials

Algal culture

The freshwater green alga Scenedesmus obliquus FACHB-416 (Chlorococcales, Chlorophyceae) can distinctly respond to infochemicals from grazers, such as cladoreans Daphnia spp. and rotifers. This alga is a common species used for inducible defense studies. S. obliquus was cultured with a modified algal growth medium BG–11 in a climate-controlled chamber at a constant temperature of 25 ± 0.5 °C with a light–dark period of 14:10 h.

Preparation of grazer infochemicals

The chemical cues that can induce anti-grazing colony formation in Scenedesmus exist in the water of herbivorous zooplanktons such as Daphnia, which feeds on Scenedesmus5,6. Therefore, addition of filtered water from Daphnia culture was used as a common method to induce colony formation. In our experiments, the grazers Daphnia magna from a laboratory clone was incubated at a density of 300 individuals per liter for 24 h feeding on S. obliquus at a density of 105cells ml−1. Then, the water was filtered through a 0.1 μm membrane filter (Millipore Corporation, USA) to eliminate bacteria and other impurities. Another suspension of S. obliquus without D. magna was filtered as control water. In preparing both control and D. magna water filtrates, phosphate was first excluded during culture medium preparation, and was added back at different concentrations after feeding for 24 h as outlined below.

Experimental procedures

Five phosphorus concentrations and five light intensity levels were established to investigate the potential costs and trade-offs of forming defensive colonies. In the experiment involving different phosphorus (P) concentrations, modified BG–11 culture media with ammonium as nitrogen source were prepared at 0.05, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, and 5.0 mg L−1 of P. K2HPO4 was applied as phosphorous resource and KCl was added to compensate for potassium shortage. The measured initial P concentrations in control groups were 0.049 (±0.009), 0.198 (±0.032), 0.515 (±0.029), 1.059 (±0.007), and 5.028 (±0.225) mg L−1, and in Daphnia filtrate groups were 0.050 (±0.004), 0.201 (±0.004), 0.525 (±0.013), 1.033 (±0.034), and 5.039 (±0.153) mg L−1. After the 7-day experiments, P concentrations decreased to 0.021 (±0.005), 0.060 (±0.011), 0.198 (±0.011), 0.719 (±0.007), 4.307 (±0.225) mg L−1 in control groups and 0.019 (±0.005), 0.069 (±0.006), 0.201 (±0.005), 0.723 (±0.050), 4.291(±0.125) in Daphnia filtrate groups. The measured initial nitrogen concentrations in control and Daphnia filtrate groups were 254.25 (±3.70) and 256.29 (±43.97) mg L−1, and it decreased to 226.17 (±34.57), 207.04 (±63.85), 227.19 (±10.06), 227.39 (±13.52), 209.48 (±16.38) mg L−1 in control groups and 236.55 (±7.54), 223.52 (±12.81), 221.69 (±6.54), 224.95 (±8.59), 217.62 (±24.30) mg L−1 in Daphnia filtrate groups. The total phosphorus and nitrogen concentrations were detected by the ammonium molybdate spectrophotometric method and the alkaline potassium persulfate digestion UV spectrophotometric method (China SEPA)58. The experimental cultures were maintained at 25 °C and illuminated at normal light level of 45μmol photons m−2 s−1 using fluorescent lights on a 14:10 light:dark cycle. Before the experiment, algal cells were starved in non-phosphate conditions for 3 days to eliminate the interference of intracellular phosphate quota. Starved algal cells were then washed with non-phosphate BG–11 medium, centrifuged at a speed of 662 g for 20 min, and placed into 250 ml Erlenmeyer flasks with different phosphorous concentrations. The initial cell density was about 7.0 × 104cells ml−1.

In the experiment involving different light intensities, culture flasks were placed separately in climate-controlled chambers at five levels of light intensity, i.e., 9, 18, 36, 54, and 72 μmol photons m−2 s−1. Algal cultures were accommodated at respective light intensities for 3 days in advance59. The initial cell density was about 2.0 × 104cells ml−1. The experimental cultures were also maintained at 25 °C on a 14:10 light:dark cycle. Both experiments had control groups and Daphnia filtrate-treated groups. Daphnia filtrate-treated groups consisted of 200 ml culture systems of S. obliquus at different P levels or light intensities with 10% (v/v) filtered Daphnia water. Control groups contained 10% filtered control water instead of Daphnia water. The measured initial P concentrations of control groups and Daphnia filtrate groups were 5.442 (±0.162) and 5.412 (±0.105) mg L−1. After the 7-day experiments, P concentrations decreased to 5.018 (±0.339), 4.902 (±0.357), 4.595 (±0.160), 4.691 (±0.214), 4.529 (±0.157) mg L−1 in control groups and 4.882 (±0.399), 4.600 (±0.076), 4.736 (±0.193), 4.761 (±0.104), 4.489 (±0.151) in Daphnia filtrate groups. The measured initial N concentrations in control and Daphnia filtrate groups were 254.66 (±25.20) and 259.95 (±35.77) mg L−1, and it decreased to 230.04 (±43.19), 224.14 (±13.56), 211.93 (±10.06), 229.22 (±11.99), 211.31 (±10.32) mg L−1 in control groups and 234.31 (±5.73), 230.24 (±9.04), 223.12 (±7.88), 218.44 (±11.14), 216.81 (±9.54) in Daphnia filtrate groups. All of the experimental cultures were established in 250 ml Erlenmeyer flasks. Erlenmeyer flasks were rotated artificially twice a day to keep the algal cells in suspension.

Experimental measurements

Samples (1 ml) of every control and Daphnia filtrate-treated groups were taken at 9:00 a.m. every day under aseptic conditions. Lugol’s iodine solution was added at 2% as preservative after sampling. Two major quantitative traits, namely, population growth and colony size, were measured. Population growth was calculated based on cell density, which was counted using a hemocytometer (0.1 mm deep) on an Olympus microscope (Olympus 6V20WHAL; Tokyo, Japan). Eighteen 0.1 mm3 count areas of one sample were observed and analyzed. Growth rate was obtained as the mean slope of ln (S. obliquus cells ml−1) over time. The mean numbers of cells per particle were also calculated from the above counts (cell abundances and cells in different morphological particles). The number of cells per particle (C) versus cultural time (t) at all P concentrations and light intensities were fitted by using a Gaussian distribution:

where Cmax is the maximum number of cells per particle, t0 is the time to reach Cmax, and a is the full width at half maximum intensity of the curve. To determine the relationship between resource availability and defensive colony formation, the observed number of Cmax was plotted against P concentration and light intensity.

Samples (2 ml) of each group were taken every day for the measurement of photosynthetic efficiency with the PHYTO-PAM phytoplankton analyzer (Heinz Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany). The maximal efficiency of PSII photochemistry was determined as Fv/Fm, where Fv = (Fm − F0), and Fm and F0 are the maximal and minimal chlorophyll fluorescence yield of a dark-adapted suspension, respectively. The effective quantum yield of PSII (ΦPSII) was calculated according to the following expression: (F’m − Fs)/F’m, where Fs and F’m are the stable and maximal chlorophyll fluorescence in light-acclimated algal suspensions, respectively. The electron transport rate (ETR) versus irradiance (PAR) curve was plotted for 20 different PARs within the range of 0–2000 μmol protons m−2s−1. The maximal electron transport rate (ETRmax) was determined from a curve after fitting it to the model proposed by Platt et al.60.

Statistical analyses

All values are presented as mean ±SE. Growth rates and numbers of cells per particle were compared by two-way ANOVA with P concentration or light intensity and Daphnia filtrate as the fixed factors. Three-way ANOVA was used to compare the differences and interactions among different environmental resource levels (P or light separately), Daphnia filtrates, and time. All data were analyzed using SigmaPlot 11.0.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Zhu, X. et al. Costs and trade-offs of grazer-induced defenses in Scenedesmus under deficient resource. Sci. Rep. 6, 22594; doi: 10.1038/srep22594 (2016).

References

Reynolds, C. S. Vegetation processes in the pelagic: a model for ecosystem theory. Vol. 37 (Ecology Institute, Oldendorf/Luhe, 1997).

Reynolds, C. S. et al. Ecology of phytoplankton. Vol. 535 (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Burkholder, J. M. In Encyclopedia of inland waters Vol. 18 (ed E. Gene Likens ) 264–285 (Elsevier, 2009).

Tang, K. W. Grazing and colony size development in Phaeocystis globosa (Prymnesiophyceae): The role of a chemical signal. J. Plankton Res. 25, 831–842 (2003).

Hessen, D. O. & Van Donk, E. Morpholigical changes in Scenedesmus induced by substances released from Daphnia . Arch. Hydrobol. 127, 129–140 (1993).

Lampert, W., Rothhaupt, K. O. & Von Elert, E. Chemical induction of colony formation in a green alga (Scenedesmus acutus) by grazers (Daphnia). Limnol. Oceanogr. 39, 1543–1550 (1994).

Trainor, F. R., Cain, J. R. & Shubert, L. E. Morphology and nutrition of the colonial green alga Scenedesmus: 80 years later. Bot. Rev. 42, 5–25 (1976).

Trainor, F. R. Reproduction in Scenedesmus . Algae (Korean J. Phycol.) 11, 183–201 (1996).

Siver, P. & Trainor, F. Effect of growth rate on unicell production in two strains of Scenedesmus (Chlorophyta). Phycologia 22, 127–131 (1983).

Lürling, M. Phenotypic plasticity in the green algae Desmodesmus and Scenedesmus with special reference to the induction of defensive morphology. Ann. Limnol.–Int. J. Lim. 39, 85–101 (2003).

Yang, Z., Kong, F. X., Shi, X. L. & Cao, H. S. Morphological response of Microcystis aeruginosa to grazing by different sorts of zooplankton. Hydrobiologia 563, 225–230 (2006).

Van Donk, E., Lürling, M. & Lampert, W. Consumer-induced changes in phytoplankton: inducibility, costs, benefits, and the impact on grazers. In Ecology & Evolution of Inducible Defenses (eds Tollrian, R., Harvell, C. D. ) 89–104 (Princeton University Press, 1999).

Jakobsen, H. H. & Tang, K. W. Effects of protozoan grazing on colony formation in Phaeocystis globosa (Prymnesiophyceae) and the potential costs and benefits. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 27, 261–273 (2002).

Agrawal, A. A. Induced responses to herbivory and increased plant performance. Science 279, 1201–1202 (1998).

Lürling, M. & Van Donk, E. Zooplankton-induced unicell-colony transformation in Scenedesmus acutus and its effect on growth of herbivore Daphnia . Oecologia 108, 432–437 (1996).

Verschoor, A. M., Zadereev, Y. S. & Mooij, W. M. Infochemical-mediated trophic interactions between the rotifer Brachionus calyciflorus and its food algae. Limnol. Oceanogr. 52, 2109–2119 (2007).

Dodson, S. I. Predation of Heterocope septentrionalis on two species of Daphnia: morphological defenses and their cost. Ecology 65, 1249–1257 (1984).

Lürling, M. & Van Donk, E. Grazer-induced colony formation in Scenedesmus: are there costs to being colonial? Oikos 88, 111–118 (2000).

Kirk, J. T. O. Light and photosynthesis in aquatic ecosystems. (Cambridge University Press, 1994).

Siver, P. A. & Trainor, F. R. Morphological control and physiology of Scenedesmus strain 170. Phycologia 20, 1–11 (1981).

Reynolds, C. S., Thompson, J. M., Ferguson, A. J. D. & Wiseman, S. W. Loss processes in the population dynamics of phytoplankton maintained in closed systems. J. Plankton Res. 4, 561–600 (1982).

O’Donnell, D. R., Fey, S. B. & Cottingham, K. L. Nutrient availability influences kairomone-induced defenses in Scenedesmus acutus (Chlorophyceae). J. Plankton Res. 35, 191–200 (2013).

Yokota, K. & Sterner, R. W. Trade-offs limiting the evolution of coloniality: ecological displacement rates used to measure small costs. P. Roy. Soc. B–Biol. Sci. 278, 458–463 (2011).

Yang, Z., Kong, F. X., Shi, X. L., Xing, P. & Zhang, M. Effects of Daphnia-associated infochemicals on the morphology, polysaccharides content and PSII-efficiency in Scenedesmus obliquus . Int. Rev. Hydrobiol. 92, 618–625 (2007).

Zhu, X. X., Wang, J., Lu, Y., Chen, Q. & Yang, Z. Grazer-induced morphological defense in Scenedesmus obliquus is affected by competition against Microcystis aeruginosa . Sci. Rep. 5, 12743 (2015).

Lürling, M. & Van Donk, E. Grazer-induced colony formation in Scenedesmus acutus (chlorophyceae): ecomorph expression at different temperatures. J. Phycol. 35, 1120–1126 (1999).

Darrow, K. & Bowers, M. D. Effects of herbivore damage and nutrient level on induction of iridoid glycosides in Plantago lanceolata . J. Chem. Ecol. 25, 1427–1440 (1999).

Weinberger, F. et al. Effects of limitation stress and of disruptive stress on induced antigrazing defense in the bladder wrack Fucus vesiculosus . Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 427, 83–94 (2011).

Wang, X., Wang, Y., Ou, L., He, X. & Chen, D. Allocation costs associated with induced defense in Phaeocystis globosa (Prymnesiophyceae): the effects of nutrient availability. Sci. Rep. 5, 10850 (2015).

Brönmark, C. et al. Costs of inducible defence along a resource gradient. PLoS ONE 7, e30467 (2012).

Steiner, U. K. Investment in defense and cost of predator-induced defense along a resource gradient. Oecologia 152, 201–210 (2007).

Thornton, D. Diatom aggregation in the sea: mechanisms and ecological implications. Eur. J. Phycol. 37, 149–161 (2002).

Heil, M. Ecological costs of induced resistance. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5, 345–350 (2002).

Tollrian, R., Duggen, S., Weiss, L. C., Laforsch, C. & Kopp, M. Density-dependent adjustment of inducible defenses. Sci. Rep. 5, 12736 (2015).

Zhu, X. X. et al. Potential grazing intensity directly determines the extent of grazer-induced colony formation in Scenedesmus obliquus . Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 61, 271–277 (2015).

Stamp, N. Out of the quagmire of plant defense hypotheses. Q. Rev. Biol. 78, 23–55 (2003).

Theodorou, M. E., Elrifi, I. R., Turpin, D. H. & Plaxton, W. C. Effects of phosphorus limitation on respiratory metabolism in the green alga Selenastrum minutum . Plant Physiol. 95, 1089–1095 (1991).

Napoléon, C., Raimbault, V. & Claquin, P. Influence of nutrient stress on the relationships between PAM measurements and carbon incorporation in four phytoplankton species. PLoS ONE 8, e66423 (2013).

Geider, R., Macintyre, L., Graziano, L. & McKay, R. M. Responses of the photosynthetic apparatus of Dunaliella tertiolecta (Chlorophyceae) to nitrogen and phosphorus limitation. Eur. J. Phycol. 33, 315–332 (1998).

Falkowski, P. G. & Woodhead, A. D. Primary productivity and biogeochemical cycles in the sea. (Springer, 2009).

Pieters, A. J. Low sink demand limits photosynthesis under P(i) deficiency. J. Exp. Bot. 52, 1083–1091 (2001).

Litchman, E., Steiner, D. & Bossard, P. Photosynthetic and growth responses of three freshwater algae to phosphorus limitation and daylength. Freshw. Biol. 48, 2141–2148 (2003).

Badr, N. B. E., Hussein, M. M. A., Badr, N. B. E. & Hussein, M. M. A. An input/ output flux model of total phosphorous in Lake Edku, a northern eutrophic Nile Delta Lake. Global J. Environ. Res. 4, 64–75 (2010).

Ho, S., Chen, C. & Chang, J. Effect of light intensity and nitrogen starvation on CO2 fixation and lipid/carbohydrate production of an indigenous microalga Scenedesmus obliquus CNW–N. Bioresour. Technol. 113, 244–252 (2012).

Xue, S., Su, Z. & Cong, W. Growth of Spirulina platensis enhanced under intermittent illumination. J. Biotechnol. 151, 271–277 (2011).

Sukenik, A. & Wahnon, R. Biochemical quality of marine unicellular algae with special emphasis on lipid composition. I. Isochrysis galbana. Aquaculture 97, 61–72 (1991).

Dubinsky, Z. & Schofield, O. From the light to the darkness: thriving at the light extremes in the oceans. Hydrobiologia 639, 153–171 (2010).

Coley, P. D., Bryant, J. P. & Chapin, F. S. Resource availability and plant antiherbivore defense. Science 230, 895–899 (1985).

DeAngelis, D. L., Ju, S., Liu, R., Bryant, J. P. & Gourley, S. A. Plant allocation of carbon to defense as a function of herbivory, light and nutrient availability. Theor. Ecol. 5, 445–456 (2012).

Bryant, J. P. & Klein, D. R. Carbon/nutrient balance of boreal plants in relation to vertebrate herbivory. Oikos 40, 357–368 (1983).

Lundgren, V. & Li, E. G. Grazer-induced defence in Phaeocystis globosa (Prymnesiophyceae): Influence of different nutrient conditions. Limnol. Oceanogr. 55, 1965–1976 (2010).

Purrington, C. B. Costs of resistance. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 3, 305–308 (2000).

Jones, C. G. & Hartley, S. E. A protein competition model of phenolic allocation. Oikos 86, 27–44 (1999).

Lürling, M. Effects of a surfactant (FFD-6) on Scenedesmus morphology and growth under different nutrient conditions. Chemosphere 62, 1351–1358 (2006).

Agrawal, A. A. & Stout, M. J. Costs of induced responses and tolerance to herbivory in male and female fitness components of wild radish. Evolution 53, 1093–1104 (1999).

Kindlmann, P., Dixon, A. F. G. & Michaud, J. P. Aphid biodiversity under environmental change: patterns and processes. (Springer, 2010).

Pilson, D. The evolution of plant response to herbivory: simultaneously considering resistance and tolerance in Brassica rapa . Evol. Ecol. 14, 457–489 (2000).

China State Environmental Protection Administration (China SEPA). Water and exhausted water monitoring analysis method. (China Environmental Science Press, 2002).

Sousa, C., Compadre, A., Vermuë, M. H. & Wijffels, R. H. Effect of oxygen at low and high light intensities on the growth of Neochloris oleoabundans . Algal Res. 2, 122–126 (2013).

Platt, T., Gallegos, C. L. & Harrison, W. G. Photoinhibition of photosynthesis in natural assemblages of marine phytoplankton. J. Mar. Res. 38, 687–701 (1980).

Acknowledgements

We thank the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31470508), NSFC for Talents Training in Basic Science (J1103507), and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Y. conceived this study; X.X.Z. designed the experiments; X.X.Z., J.W., Q.W.C. and G.C. performed the experiments; X.X.Z., Z.Y. and Y.H. conducted the data analysis and prepared figures and tables. X.X.Z. and Z.Y. wrote the manuscript. All of the authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, X., Wang, J., Chen, Q. et al. Costs and trade-offs of grazer-induced defenses in Scenedesmus under deficient resource. Sci Rep 6, 22594 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22594

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22594

This article is cited by

-

Long-term continuous mismatch between grazing cues and real grazing losses causes attenuation of induced morphological defense in Scenedesmus

Journal of Applied Phycology (2024)

-

The evolution of convex trade-offs enables the transition towards multicellularity

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Predator-induced defence in a dinoflagellate generates benefits without direct costs

The ISME Journal (2021)

-

Rotifers release a lipid-soluble agent that inhibits photosynthetic electron transport in Chlorella sp

Journal of Applied Phycology (2021)

-

Grazing resistance in phytoplankton

Hydrobiologia (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.