Abstract

Arrays of sub-wavelength, sub-10 nm air-gap plasmonic ring resonators are fabricated using nanoimprinting. In near infra-red (NIR) range, the resonator supports a single dipole mode which is excited and identified via simple normal illumination and explored through transmission measurements. By controlling both lateral and vertical confinement via a metal edge, the mode volume is successfully reduced down to 1.3 × 10−5 λ03. The advantage of such mode confinement is demonstrated by applying the resonators biosensing. Using bovine serum albumin (BSA) molecules, a dramatic enhancement of surface sensitivity up to 69 nm/nm is achieved as the modal height approaches the thickness of the adsorbed molecule layers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The propagation of electromagnetic waves can be manipulated at the nanoscale using metallic nanostructures, via coupling with surface plasmons1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. In case of noble metals, their high plasma frequency and relatively low Ohmic resistivity result in a very high absolute value of Re(ϵ) in the infra-red. Thus, when two such noble metal parts separated by a narrow gap are used for coupling with electromagnetic waves, the requirement for continuity of the perpendicular D-field component results in a huge enhancement of the electric field in the gap. Such a strong enhancement of the E-field in a small volume is highly advantageous not only for many diverse applications such as sensors10,11,12,13, lasers14,15,16,17 and color displays18,19,20,21 but also for fundamental control of optical phenomena22,23. Consequently, such gap structures, also called metal-insulator-metal (MIM) structures24 or gap plasmons25, have been the subject of intense research activities26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35.

A widely used method to fabricate such a narrow gap structure is to form a vertical gap by etching through a metal film using either focused ion-beam (FIB) or electron-beam lithography11,12,13,36,37. Precise drawings of arbitrary shapes are possible, but at the cost of long process time and high fabrication cost. Furthermore, such methods are difficult to scale up to a large-scale fabrication. An alternative method is to define a gap via sequential deposition of metal, dielectric and metal thin films15,21,22,26,29,38. In this case, smooth, nm-thin gaps can be fabricated with relative ease, as they are defined simply by the deposited dielectric layer. However, the physical presence of the dielectric layer prevents access to the high E-field from outside (e.g. by chemical analytes), significantly limiting the range of possible applications. Furthermore, as the gap confines the E-field in one direction only (i.e., the field component perpendicular to the gap), the optical field can spread extensively parallel to the metal layers.

Indeed, for an effective confinement of the optical field, careful design of the metal structure beyond mere gap formation is necessary. One structure that was shown to be effective for tight field confinement is a T-shaped gap in which a sharp tip is placed above a metal layer39. Unfortunately, fully controlled three-dimensional fabrication of such a T-shaped gap is difficult to achieve using either vertical or horizontal gap structures. Recently, we have reported on fabricating a ring resonator with such a junction structure using a directional deposition of metal onto a slot-disk. In this way the T-shaped gap is formed along the circumference of the disk between the sidewall of the top disk and the top surface of the bottom disk. A gap as narrow as 4 nm, with a cross-sectional mode area of 7 × 10−5 λ02 could be fabricated using photolithography and the possibility of application for a biosensor was demonstrated35. However, the resonators were rather large, with a diameter of 3.5 μm, leading to large overall mode volume. Moreover, the excitation and detection of resonances required a tapered fiber coupling, which does not lend to easy, cost-effective applications.

In this paper, we report on fabricating a large-area array of sub-wavelength sized disk resonators, with T-shaped metal air-gap of sub 10-nm size controlled via deposition method27,31,40. The T-shaped gap confines the optical mode laterally and vertically, while the sub-wavelength size of the resonator localizes the optical mode longitudinally. Consequently, the resonator supports only a single dipole mode near the wavelength of 1500 nm with a mode volume of only 1.3 × 10−5 λ03 that can be excited efficiently by simple top illumination. Furthermore, the high density of uniform resonators in the array, made possible by nanoimprinting, results in very high transmission efficiency of 1.4~13% such that the plasmon resonance can easily be explored in simple transmission measurements. Finally, we demonstrate the advantage of such resonator arrays for biosensor applications. For surface coverage of the BSA molecules, the gap mode showed surface sensitivity up to 69 nm/nm as the modal height approaches the thickness of the adsorbed BSA layers.

Results

Formation of the 5-nm air gap

The fabrication process for the resonator arrays are summarized in Fig. 1a. First, a SiNx/SiO2/SiNx multilayer film was deposited on a quartz substrate. Afterward, a hexagonal array of polymer pillars with 200 nm diameter and 800 nm pitch was formed via nanoimprinting method41. Using the pillars as etch masks, SiNx disks were formed in the top SiNx layer. The SiO2 layer was then etched selectively using buffered oxide etchant to undercut the SiN disks, thus forming a slot. Finally, an Au layer with a Cr adhesion layer was deposited to form MIM structure at the edges of the SiNx slots (See method section for more details). A scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the imprinted pillars are shown in Fig. 1b and an SEM image of the final resonator array is shown in Fig. 1c. A large array of uniformly sized, button-shaped resonators on the basal metal layer can be seen. More details about the structure can be seen in Fig. 1d–f, which shows the cross-sectional transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of the resonators. We find that the presence of the undercut slot effectively turns the top disk into a shadow mask during the metal deposition such that after the deposition, a well-defined gap is formed between the metal cap on the top SiNx disk and the basal metal layer on the bottom SiNx layer. Moreover, despite of the shadowing by the top disk, the basal gold layer extends into the gap below the top SiN disk, while the bottom edge of the sidewalls of the top gold cap forms a rounded tip opposite to the top surface of the basal Au bottom ring due to the self-shadowing effect. Furthermore, as the gap is defined by deposition, the root-mean-square (RMS) roughness of the surfaces is 0.8 nm only35. The result is a narrow, T-shaped gap that confines the E-field both vertically and laterally. The degree of lateral and vertical confinement can be controlled with nanometer precision by controlling the SiO2 spacer layer thickness and the metal thickness and the size of the disk determines the longitudinal confinement via the resonance condition of the whispering gallery mode (WGM). The final gap size, defined to be the shortest distance between the bottom edge of the top gold gap and the basal gold layer, could be controlled down to 5 nm. An analysis of TEM images of a series of 5-nm gap resonators fabricated under identical conditions indicated a standard deviation of 1.6 nm in the gap sizes as well.

Fabrication of the plasmonic air-gap ring resonator arrays.

(a) Schematics of the fabrication process in cross-sectional view. (b) SEM image of imprinted pillar arrays on the multilayers. (c) SEM image of the fabricated resonator arrays. (d–f) TEM cross-section image of the resonator fabricated with different gap sizes of (d) 40 nm, (e) 15 nm and (f) 5 nm. The materials are indicated on each regions. The other regions of the TEM images, are protection films coated just before FIB milling.

Calculated plasmon modes in the air-gap resonator

Figure 2a,b show transmission spectra with varying gap sizes (2.5 nm to 50 nm) and two different metal thickness (45 nm and 90 nm), as calculated by finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulations. We find that in the near infra-red rage of λ > 800 nm, there exist only a single transmission peak that blueshifts with increasing gap size and metal thickness34,35,39. The transmission peak appears to split into two as the gap size increase beyond 15 nm. However, this is due to a transmission minimum located at λ = 1,142 nm, as shall be shown later. Figure 2c–h show the calculated optical modes at wavelengths corresponding to transmission peak, as indicated in Fig. 2a,b. Actual structures obtained from TEM images (as shown in Fig. 1d–f) were used in calculations. We find that the transmission peaks correspond to excitation of dipole-like plasmonic WGM, confined tightly within the T-shaped gap along the circumference of the disk. Consequently, the overall mode volume is very small – as small as 1.3 × 10−5 λ03 for the resonator shown in Fig. 2e–h. We also note that such concentration of the mode in the air gap also indicates that the mode is an anti-symmetric mode, where the charges on the basal metal layer and the charges on the tip of the sidewall edge have opposite signs. The absence of other resonance modes in our spectra is ascribed to the resonator’s small size and highly non-symmetric shape that were shown to favor excitation of dipole-like modes35. The transmission can be quite high – as high as 18% of the incident light for the 40 nm gap resonator, even though the gap size is much smaller than the wavelength of the incident light and in any case, the gaps are invisible in the Au film when viewed vertically due to the overlap of the top Au disks and the basal Au layer. This is because the gap-plasmonic WGM acts as a channel which, at resonance, selectively funnels the incident light through the gap and out into the far field. This can be seen in Fig. 2h that shows the calculated electric field intensity of the resonance modes in logarithm scale. The Supplementary Movie S1 (a) and (b) also show propagations of resonant and non-resonant light, respectively, normally incident on a 5-nm gap resonator. At resonance, the incident wave is funneled through the gap so that a large fraction of the incident light is transmitted. Off resonance, the incident wave is nearly completely reflected, with very little transmission through the resonator.

FDTD Simulations.

(a,b) Calculated transmission spectra upon varying gap sizes and metal thicknesses of (a) 45 nm and (b) 90 nm. The resonance wavelengths for each modes are indicated as white dashed lines. (c–e) |E|2 distributions of the resonance modes calculated based on structures reconstructed from the TEM images. (c) Cross-sectional view of the mode of the 40 nm gap resonator (Fig. 1d), (d) mode of 15 nm gap resonator (Fig. 1e), (e) mode of 5 nm gap resonator (Fig. 1f). (f,g) Normal components of the E-field (Ez), (f) shows the top view of the mode of the 5 nm gap resonator in the plane of the air-gap, while (g) shows the cross-sectional view of same mode. (h) Cross-sectional Log|E|2 distribution of the mode in the 5 nm gap resonator.

Measurement of resonant transmission through the gap

The dipole-like gap-plasmonic WGMs also enable their efficient excitation by vertical illumination and their observation in a simple transmission measurement. Figure 3a–f show the calculated and measured transmission spectra for the resonator arrays shown in Fig. 1d–f. The agreement between measured and observed spectra is excellent, with an experimental transmission of 13% obtained from the resonator with 15 nm gap. The transmission is reduced to 1.4% for the resonator with 5 nm gap, but even in this case, the signal to noise ratio for the gap plamonic WGM is as high as 100. For all resonators, a dip in the transmission at 1142 nm is clearly evident, as discussed above. The position of this dip is independent of the gap size and corresponds to excitation of guided mode resonance (GMR)42 due to the periodic boundary conditions of the array structures. This is confirmed by Fig. 3g,h, which show that at 1142 nm, the E-field is concentrated in spaces between the disks, with exactly one wavelength of the propagating wave fitting into the space between the nearest neighbors in the SiNx layer underneath the basal Au film. Indeed, as Fig. 3i shows, the position of the dip is calculated to be proportional to the pitch.

Transmission spectra.

(a–f) Transmission spectra of the ring resonator arrays, (a) experimental and (b). FDTD simulated transmission spectra of the 40 nm gap resonator (Fig. 1d), (c,d) same for 15 nm gap resonator (Fig. 1e), (e,f) same for the 5 nm gap resonator (Fig. 1f). (g,h) Top view of normal components of the E-field (Ez) in the plane of the SiNx layer underneath the Au film when 1,141 nm light, coincident with the dip, is incident normally upon the array of the resonators of 40 nm gap, with polarizations of Ex (g) and Ey (h). Black circles indicate the positions of the resonators. (i) Calculated transmission spectra of the ring resonators arrays when the pitch is varied from 800 nm to 1,200 nm.

Surface sensitivity

In order to confirm the results of simulations and measurements and to reveal the advantage of the resonator structures, we demonstrate sensitivity for surface change of the resonator arrays. We first investigate numerically the sensitivity of the resonator structure. As shown in Fig. 4a, when the structures are fully emerged in an analyte, the bulk sensitivity is estimated to be 800~1,500 nm/RIU, quite high among the resonator-based sensors but modest when compared to existing Kretschmann SPR systems43. However, we note that bulk sensitivity is simply proportional to the extension of the optical mode into the analyte and does not fully reflect the advantage of the molecular range optical confinement provided by gap plasmon resonators. This is demonstrated in Fig. 4b, which shows the calculated values of surface sensitivity, defined to be the resonance peak shift per unit thickness of the adsorbed analyte material44,45,46,47, assuming a refractive index of BSA48,49, as a model analyte. We find that, as expected, narrower gaps give higher sensitivity. At the same time, it is also clear that such high sensitivity is obtained at the cost of dynamic range, as the peak shift quickly saturates for the narrowest gap resonators.

Biosensing.

(a) Calculated bulk sensitivities of the resonators with 5 nm, 15 nm and 40 nm gaps. (b) Calculated resonance peak shifts due to surface layer adsorption of BSA. (c–e) Transmission spectra of the (c) 40-nm gap, (d) 15-nm gap and (e) 5-nm gap resonators before (black) and after (red) surface saturation with 10% BSA solution. (f) Calculated (red) and experimental (black) dependence of the peak shift on the gap size, after surface saturation with 10% BSA solution. (g) Experimental Q factor acquired from the Loretzian fitting (inset) and (h) FOM. All measurements and calculations were conducted against air-background and error bars represents the standard deviations of gap sizes measured from TEM images.

The calculated surface sensitivity is confirmed experimentally by observing the shift of the resonance peak upon covering the resonator array with a monolayer of BSA, as saturation coverage of Au films with BSA is reported to result in formation of a monolayer of 3.5 nm thickness and 1.5 refractive index49,50,51. BSA layer was formed by dipping the array structure in a 10% BSA solution for 3 hrs at room temperature. The uniformity of the BSA layer was confirmed by the near independence of the changes in the transmission spectra upon the location of the beam spot (data not shown). Figure 4c–e shows the measured transmission spectra for resonator arrays shown in Figs 1, 2, 3 after BSA coverage. For the resonators with large gaps, an accurate estimate of the peak shift is difficult due to the presence of the transmission dip at 1142 nm, as discussed above. However, for resonators with estimated gap sizes of 15 nm and 5 nm, a clear shift of 75 nm and 250 nm, corresponding to surface sensitivity of 21 nm/nm and 69 nm/nm, respectively, can be observed. We note that it is possible to shrink the gap even further to 3 nm, which would give an even higher peak shift; however, experimental verification of such a large shift was not possible due to limitations of our measurement setup (See Supplementary Figure S2 online). The dependence of the peak shift upon the gap sizes is summarized in Fig. 4f. As shown in Fig. 4f, the experimental value agrees very well with calculated value when the gap size is large (15 nm). In case of resonators with smaller gaps (5 nm ~12 nm), the experimentally observed peak shifts are smaller than the theoretically predicted values, which we attribute to difficulty of the BSA molecules in fully penetrating the gap that is smaller than the size of BSA molecule (4 nm × 4 nm × 14 nm)52.

Q factor and Figure of merit (FOM)

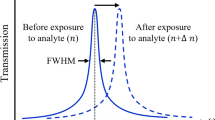

For biosensing and many other applications, another important resonator parameter is the Q factor of the resonator. Figure 4g shows the measured and calculated Q factors of resonators with different gap sizes, as obtained from Lorentzian fittings on the experimental transmission spectra. As the gap size decreases from 15 nm to 5 nm with concomitant decrease of mode volume from 8.2 × 10−5 λ03 to 1.3 × 10−5 λ03 and increase in the surface sensitivity from 21 nm/nm to 69 nm/nm, the Q factor remains nearly constant, decreasing from 7.2 to 6.2 only. Consequently, the FOM of the resonator-based biosesnors, which we define to be FOM = (Sensitivity/FWHM)53 is also highly enhanced upon reduction of the gap sizes, as shown in Fig. 4h.

Discussions

The demonstrated mode volume 1.3 × 10−5 λ03 is one of the smallest values ever reported for WGM resonators38. Indeed, the mode volume is smaller than even that of a bow-tie antenna16 and clearly demonstrates the advantage of the present structure in providing such a high degree of 3-dimensional confinement. In fact, the observed 250 nm of resonance shift indicates that 30% of the mode energy is utilized to sense the monolayer of the BSA molecules, with about 60 molecules contributing to the observed peak shift. In other words, a single BSA molecule contributes, on the average, a peak shift of 4.2 nm. Therefore, given a peak position resolution of 1.2 nm (data not shown), we believe that even a single molecule in the gap can be detected, which will be demonstrated in a subsequent report. In addition, the observed surface sensitivity is among the highest values ever reported for surface sensitivity from a resonator structure, being 59, 12 and 2~3 times higher than those reported for conventional evanescent-field sensors46, dielectric-based slot resonators45 and Au/Ag nanoparticle based LSPR sensors48, respectively, when normalized by the operation wavelength. We note that a similarly high sensitivity has been reported from an LSPR sensor54, albeit for an atomic-layer deposited Al2O3 film.

However, it should be noted that the dielectric-based resonators45 tend to have far higher FOM, with values as high as 30, than LSPR-based resonators48, which typically do not exceed 0.3. This is mainly due to their high quality factors that can reach values in excess of 106, resulting in an extremely narrow FWHM55. However, measuring such a narrow resonance can be non-trivial and the factors other than FOM also affect the overall detection resolution of a biosensing system. Indeed, there have been several reports of achieving peak resolutions that are much finer than the FWHM of the resonance peaks43. For realistic biosensing applications, the gap size should be optimized for each purpose as well. As shown Fig. 4b, a narrow gap provides a high surface sensitivity, but at the cost of limited operation range. Furthermore, as Fig. 4f shows, too narrow of a gap hinder sensing of large analytes such as proteins; based on deviation of experimental data from the calculated data, we estimate that the gap size should be at least 15 nm if we wish to achieve a compact formation of a BSA layer.

It is also worth of note that the fabrication of arrays of plasmonic ring resonators with well-controlled 5-nm air-gap was realized in large-scale on a 4-inch wafer. Furthermore, given the illumination beam spot size of ~500 μm and the pitch of 800 nm, the measured transmission spectrum represents a sum of more than ~105 resonator spectra, but with limited inhomogeneous broadening. The fact that we can still measure a transmission peak with an apparent Q-factor of 7, which is in agreement with the simulation results for perfectly uniform resonators, indicates that the nanoimprinted disks are sufficiently uniform that we do not need to resort to extreme measures to obtain single-resonator spectra, which greatly facilitates use of the resonators for practical applications.

Methods

Fabrication of the resonator arrays

A SiNx /SiO2 /SiNx multilayer film was deposited on a 4 inch diameter quartz substrate using an RF sputtering method. A schematic description of the process is shown in Fig. 1a. The SiNx layer thickness was kept constant at 70 nm, while the SiO2 layer thickness was varied to be between 40 nm and 75 nm. After the multilayer deposition, a 4-inch wafer sized, hexagonal array of resin pillars with 200 nm diameter and 800 nm pitch was fabricated on the multilayer film using a nanoimprinting method with a UV-curable nanoimprinting resist (mr-UVCur06, micro resist technology GmbH)41. The scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the imprinted pillars array is shown in Fig. 1b. Afterward, the top SiNx layer was etched with an ICP-RIE method to form SiNx disks, using the nano-imprinted pillars as the etch-mask. The pillars were then removed by O2 plasma ashing and the spacer SiO2 layer was partially etched using Buffered Oxide Etchant to undercut the top SiNx disks and to form a slot, utilizing the bottom SiNx layer as the etch-stop to protect the quartz substrate. Finally, an Au layer with a Cr adhesion layer was sputter-deposited. The thickness of the Au layer was varied between 45 nm and 90 nm.

FDTD simulations

To simulate the ring resonator array structure, periodic boundary condition is used for all simulations. The , collision frequency of Au used for simulations were 40 THz. Based on the TEM images shown in Fig. 1d–f, we modelled the resonator shapes as a function of the metal thickness and spacer layer thickness. The bottom metal tip on the sidewall of the disk is assumed to be rounded and the basal metal layer is assumed to penetrate into the slot as a simple straight sloped line. The thickness of the metal tip on the sidewall, the slope and start of the slope of the bottom metal were obtained by fitting a second-order polynomial to the metal thickness and spacer layer thickness obtained from the experimentally obtained TEM images of actually fabricated samples.

Transmission measurements

The transmission measurement setup is described in Supplementary Figure S3. All the lenses, polarizers, the sample and the detector were aligned in a straight line. The incident angle was 90°, normal to the sample surface. Due to the symmetry of the resonator array and the normal angle of incidence, the transmission spectra were expected and confirmed to be, invariant to the polarization (Data not shown).

Procedures of the Biosensing experiment

To investigate the effect of a self-assembled BSA monolayer on the resonance spectra, the resonators arrays samples were treated with following process.

-

1

Cleaning

-

1.1 Rinsed with Acetone.

-

1.2 Rinsed with Methanol.

-

1.3 Rinsed with DI water.

-

1.4 Blow dried with nitrogen.

-

-

2

Resonance spectra as ‘air’ were measured.

-

3

BSA coating.

-

3.1 Dipped in the solution of BSA in PBS with concentration of 10%.

-

3.2 Stayed 3 hours at room temperature, while being continuously shaken at 120 rpm.

-

3.3 Rinsed with DI water.

-

3.4 Blow dried with nitrogen.

-

-

4

Resonance spectra as ‘with BSA’ were measured.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lee, J. et al. Ultra sub-wavelength surface plasmon confinement using air-gap, sub-wavelength ring resonator arrays. Sci. Rep. 6, 22305; doi: 10.1038/srep22305 (2016).

References

Barnes, W. L., Dereux, A. & Ebbesen, T. W. Surface plasmon subwavelength optics. Nature 424, 824–830 (2003).

Lal, S., Link, S. & Halas, N. J. Nano-optics from sensing to waveguiding. Nat. Photonics 1, 641–648 (2007).

Verhagen, E., Polman, A. & Kuipers, L. K. Nanofocusing in laterally tapered plasmonic waveguides. Opt. Express 16, 45–57 (2008).

Min, B. et al. High-Q surface-plasmon-polariton whispering-gallery microcavity. Nature 457, 455–458 (2009).

Oulton, R. F. et al. Plasmon lasers at deep subwavelength scale. Nature 461, 629–632 (2009).

Gramotnev, D. K. & Bozhevolnyi, S. I. Plasmonics beyond the diffraction limit. Nat. Photonics 4, 83–91 (2010).

Atwater, H. A. & Polman, A. Plasmonics for improved photovoltaic devices. Nat. Mater. 9, 205–213 (2010).

Berini, P. & De Leon, I. Surface plasmon–polariton amplifiers and lasers. Nat. Photonics 6, 16–24 (2011).

Juan, M. L., Righini, M. & Quidant, R. Plasmon nano-optical tweezers. Nat. Photonics 5, 349–356 (2011).

Tetz, K. A., Pang, L. & Fainman, Y. High-resolution surface plasmon resonance sensor based on linewidth-optimized nanohole array transmittance. Opt. Lett. 31, 1528–1530 (2006).

Lee, K. L., Lee, C. W., Wang, W. S. & Wei, P. K. Sensitive biosensor array using surface plasmon resonance on metallic nanoslits. J. Biomed. Opt. 12, 044023 (2007).

Zhang, W., Huang, L., Santschi, C. & Martin, O. J. Trapping and sensing 10 nm metal nanoparticles using plasmonic dipole antennas. Nano Lett. 10, 1006–1011 (2010).

Feng, J. et al. Nanoscale plasmonic interferometers for multispectral, high-throughput biochemical sensing. Nano Lett. 12, 602–609 (2012).

Vesseur, E. J. R., Garcia de Abajo, F. J. & Polman, A. Broadband purcell enhancement in plasmonic ring cavities. Phys. Rev. B 82 (2010).

Russell, K. J., Liu, T.-L., Cui, S. & Hu, E. L. Large spontaneous emission enhancement in plasmonic nanocavities. Nat. Photonics 6, 459–462 (2012).

Suh, J. Y. et al. Plasmonic bowtie nanolaser arrays. Nano Lett. 12, 5769–5774 (2012).

Song, J. H. et al. Fast and bright spontaneous emission of Er(3+) ions in metallic nanocavity. Nat. Commun. 6, 7080 (2015).

Clausen, J. S. et al. Plasmonic metasurfaces for coloration of plastic consumer products. Nano Lett. 14, 4499–4504 (2014).

Tan, S. J. et al. Plasmonic color palettes for photorealistic printing with aluminum nanostructures. Nano Lett. 14, 4023–4029 (2014).

Ye, F., Burns, M. J. & Naughton, M. J. Structured metal thin film as an asymmetric color filter: the forward and reverse plasmonic halos. Sci. Rep. 4, 7267 (2014).

Roberts, A. S., Pors, A., Albrektsen, O. & Bozhevolnyi, S. I. Subwavelength plasmonic color printing protected for ambient use. Nano Lett. 14, 783–787 (2014).

Miyazaki, H. T. & Kurokawa, Y. Squeezing visible light waves into a 3-nm-thick and 55-nm-long plasmon cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 097401 (2006).

Burgos, S. P., de Waele, R., Polman, A. & Atwater, H. A. A single-layer wide-angle negative-index metamaterial at visible frequencies. Nat. Mater. 9, 407–412 (2010).

Zia, R., Selker, M. D., Catrysse, P. B. & Brongersma, M. L. Geometries and materials for subwavelength surface plasmon modes. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 21, 2442–2446 (2004).

Smith, C. L., Stenger, N., Kristensen, A., Mortensen, N. A. & Bozhevolnyi, S. I. Gap and channeled plasmons in tapered grooves: a review. Nanoscale 7, 9355–9386 (2015).

Im, H., Bantz, K. C., Lindquist, N. C., Haynes, C. L. & Oh, S. H. Vertically oriented sub-10-nm plasmonic nanogap arrays. Nano Lett. 10, 2231–2236 (2010).

Zhu, W., Banaee, M. G., Wang, D., Chu, Y. & Crozier, K. B. Lithographically fabricated optical antennas with gaps well below 10 nm. Small 7, 1761–1766 (2011).

Saleh, A. A. & Dionne, J. A. Toward efficient optical trapping of sub-10-nm particles with coaxial plasmonic apertures. Nano Lett. 12, 5581–5586 (2012).

Chang, Y. C., Wang, S. M., Chung, H. C., Tseng, C. B. & Chang, S. H. Observation of absorption-dominated bonding dark plasmon mode from metal-insulator-metal nanodisk arrays fabricated by nanospherical-lens lithography. ACS Nano 6, 3390–3396 (2012).

Ye, F., Burns, M. J. & Naughton, M. J. Plasmonic halos–optical surface plasmon drumhead modes. Nano Lett. 13, 519–523 (2013).

Im, H. et al. Self-assembled plasmonic nanoring cavity arrays for SERS and LSPR biosensing. Adv. Mater. 25, 2678–2685 (2013).

Rahimzadegan, A., Granpayeh, N. & Hosseini, S. P. Improved plasmonic filter, ultra-compact demultiplexer and splitter. J. Kor. Opt. Soc. 18, 261–273 (2014).

Lee, D. E., Lee, T. W. & Kwon, S. H. Sub-micrometer-sized spectrometer by using plasmonic tapered channel-waveguide. J. Kor. Opt. Soc. 18, 788–792 (2014).

Siegfried, T., Wang, L., Ekinci, Y., Martin, O. J. F. & Sigg, H. Metal double layers with sub-10 nm channels. ACS Nano 8, 3700–3706 (2014).

Lee, J., Song, J., Sung, G. Y. & Shin, J. H. Plasmonic waveguide ring resonators with 4 nm air gap and λ2/15,000 mode-area fabricated using photolithography. Nano Lett. 14, 5533–5538 (2014).

Fu, Y. et al. All-optical logic gates based on nanoscale plasmonic slot waveguides. Nano Lett. 12, 5784–5790 (2012).

Huang, K. C. Y. et al. Electrically driven subwavelength optical nanocircuits. Nat. Photonics 8, 244–249 (2014).

Kuttge, M., Garcia de Abajo, F. J. & Polman, A. Ultrasmall mode volume plasmonic nanodisk resonators. Nano Lett. 10, 1537–1541 (2010).

Veronis, G. & Fan, S. Modes of subwavelength plasmonic slot waveguides. J. Lightwave Technol. 25, 2511–2521 (2007).

Ah, C. S. et al. Fabrication of integrated nanogap electrodes by surface-catalyzed chemical deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 133116 (2006).

Sung, S. et al. Advanced metal lift-offs and nanoimprint for plasmonic metal patterns. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 1, 25–30 (2014).

Rosenblatt, D., Sharon, A. & Friesem, A. A. Resonant grating waveguide structures. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 33, 2038–2059 (1997).

Roh, S., Chung, T. & Lee, B. Overview of the characteristics of micro- and nano-structured surface plasmon resonance sensors. Sensors 11, 1565–1588 (2011).

Otte, M. A. et al. Identification of the optimal spectral region for plasmonic and nanoplasmonic sensing. ACS Nano 4, 349–357 (2010).

Lee, S. et al. Label-free optical biosensing using a horizontal air-slot SiNx microdisk resonator. Opt. Express 18, 20638–20644 (2010).

Jeong, H., Lee, S., Sung, G. Y. & Shin, J. H. Design and fabrication of Tb-doped silicon oxy-nitride microdisk for biosensor applications. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 23, 88–90 (2011).

Konig, M. et al. Unveiling the correlation between nanometer-thick molecular monolayer sensitivity and near-field enhancement and localization in coupled plasmonic oligomers. ACS Nano 8, 9188–9198 (2014).

Jia, K. et al. Strong improvements of localized surface plasmon resonance sensitivity by using Au/Ag bimetallic nanostructures modified with polydopamine films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 219–227 (2014).

Phan, H. T., Bartelt Hunt, S., Rodenhausen, K. B., Schubert, M. & Bartz, J. C. Investigation of bovine serum albumin (BSA) attachment onto self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) using combinatorial quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation (QCM-D) and spectroscopic ellipsometry (SE). PloS one 10, 0141282 (2015).

Benesch, J., Askendal, A. & Tengvall, P. The determination of thickness and surface mass density of mesothick immunoprecipitate layers by null ellipsometry and protein 125iodine labeling. Journal of colloid and interface science 249, 84–90 (2002).

Voros, J. The density and refractive index of adsorbing protein layers. Biophys. J. 87, 553–561 (2004).

Wright, A. K. & Thompson, M. R. Hydrodynamic structures of bovine serum albumin determined by transient electric birefringence. Biophys. J. 15, 137–141 (1975).

Lodewijks, K., Van Roy, W., Borghs, G., Lagae, L. & Van Dorpe, P. Boosting the figure-of-merit of LSPR-based refractive index sensing by phase-sensitive measurements. Nano Lett. 12, 1655–1659 (2012).

Whitney, A. V. et al. Localized surface plasmon resonance nanosensor: a high-resolution distance-dependence study using atomic layer deposition. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 20522–20528 (2005).

Baaske, M. & Vollmer, F. Optical resonator biosensors: molecular diagnostic and nanoparticle detection on an integrated platform. Chemphyschem: a European journal of chemical physics and physical chemistry 13, 427–436 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Global Frontier Program (NRF-2014M3A6B3063708), GRL (K20815000003-11A0500-00310) and by the Pioneer Research Center Program (2014M3C1A3052537) through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning and by Danish-Korean International Network Programme, Danish Agency for Science, Technology and Innovation through (Grant No. 1370-00035A).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. and J.S. conceived the experiment and analyzed the data. S.S. and J.C. performed nanoimprints. S.E. wrote the FDTD code. J.L., J.S. and N.A. discussed the results and wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J., Sung, S., Choi, JH. et al. Ultra sub-wavelength surface plasmon confinement using air-gap, sub-wavelength ring resonator arrays. Sci Rep 6, 22305 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22305

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22305

This article is cited by

-

Improved design of all-optical half-adder and half-subtractor circuits using MIM plasmonic waveguides for optical networks

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2023)

-

Plasmonic colour generation

Nature Reviews Materials (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.