Abstract

Normal uptake, transportation and assimilation of primary nutrients are essential to plant growth. Tracheary elements (TEs) are tissues responsible for the transport of water and minerals and characterized by patterned secondary cell wall (SCW) thickening. Exocysts are involved in the regulation of SCW deposition by mediating the targeted transport of materials and enzymes to specific membrane areas. EXO70s are highly duplicated in plants and provide exocysts with functional specificity. In this study, we report the isolation of a rice mutant rapid leaf senescence2 (rls2) that exhibits dwarfism, ferruginous spotted necrotic leaves, decreased hydraulic transport and disordered primary nutrient assimilation. Histological analysis of rls2-1 mutants has indicated impaired cell expansion, collapsed vascular tissues and irregular SCW deposition. Map-based cloning has revealed that RLS2 encodes OsEXO70A1, which is one of the 47 members of EXO70s in rice. RLS2 was widely expressed and spatially restricted in vascular bundles. Subcellular localization analysis demonstrated that RLS2 was present on both membrane and nuclear regions. Expression analysis revealed that mutations in rls2 triggers transcriptional fluctuation of orthologous EXO70 genes and affects genes involved in primary nutrient absorption and transport. In brief, our study revealed that RLS2 is required for normal vascular bundle differentiation and primary nutrient assimilation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Primary nutrients, including nitrogen (N), phosphorus (Pi) and potassium ion (K+), are essential for plant growth and are required in larger quantities than other nutrients. The mechanism of absorption, transportation and assimilation of these three primary nutrients has been extensively studied in Arabidopsis and rice1,2,3,4,5,6,7. PHO2, miR399 and PHR1 are involved in plant Pi signaling. PHR1 is activated by Pi deficiency and promotes the accumulation of miR399, which subsequently regulates the UBC protein PHO2 at the transcription level. PHO2 and NLA-mediated ubiquitination monitors the expression of a subset of phosphate starvation-induced (PSI) genes, including Pi transporter genes8,9,10. Plants use mainly inorganic nitrogen nitrate in aerobic uplands and use ammonium in flooded anaerobic paddy fields. Members of the NRT2 family play a major role in nitrate uptake11,12, whereas those of the OsAMT1 family are involved in NH4+ transport in rice plants13,14. K+ is the most abundant cation in living cells and maintains cellular electroneutrality and osmotic equilibrium. Transport of K+ from the soil to its final destination in plants is mediated by channels and transporters. K+ channels are not restricted to the plasma membrane (PM), but are also widely distributed across other membrane systems. Os-AKT1, which is thought to be the most important component that is involved in K+ uptake in rice roots, is located in the PM6. Pore K+ (TPK) channel family genes, which encode vacuole-specific K+ transporters, play an important role in maintaining K+ homeostasis5. K+ efflux antiporter (KEA) genes encode putative potassium efflux antiporters that are mainly located in the chloroplast15. However, how integral membrane proteins arrive at specific destinations in plants is unknown.

Tracheary elements (TEs), which are responsible for the transport of water and minerals in terrestrial plants, are characterized by secondary cell wall (SCW) thickening that present an elaborate pattern16. Deposition of lignified secondary walls in TEs facilitates waterproofing for efficient water transport and promotes resistance to the negative pressure generated during transpiration. It is well known that cortical microtubules play crucial roles in the patterned deposition of secondary walls17. The observation of fluorescent protein-fused CesAs reveals that CesA complexes move along the track of cortical microtubules located beneath the PM18. AtKTN1 encodes a katanin microtubule-severing protein that is essential for the organization of cortical microtubules and a mutation in this gene causes aberrant orientation of cellulose microfibrils19,20. Cortical microtubule bundles control the patterned deposition of secondary walls by directing the targeted transport of vesicles carrying materials and enzymes to specific PM domains21,22.

The tethering complexes, which are assembled with eight proteins (Sec3, Sec5, Sec6, Sec8, Sec10, Sec15, Exo70 and Exo84) on the vesicle membrane mediate the docking of secretory vesicles on the target membrane23,24. Bioinformatics analysis has identified homologs corresponding to these eight exocyst proteins in plants25,26,27. Interestingly, compared to the single copy that predominates in other eukaryotes, a striking feature of plants is that exocyst complex genes have evolved multiple paralogs25,28. Plant genomes encode a large number of EXO70 copies, for example, 23 EXO70 copies exist in Arabidopsis thaliana, whereas 47 occur in rice (Oryza sativa)28. Investigations of plant EXO70 family genes are in its early stages and only a few EXO70 paralogs have been reported in Arabidopsis. The distinct and tissue-specific expression patterns of EXO70 members are suggestive of its functional divergence and specificity in regulating cell-type specific exocytosis or cargo-specific exocytosis26,28,29. The expression of EXO70B2 and EXO70H1 are upregulated during Pseudomonas syringae infection and are involved in the plant-pathogen interaction in Arabidopsis30,31. EXO70C1 is highly expressed in guard cells and pollen grains and is critical for pollen tube growth32. A recent report indicated that EXO70H4 is essential for trichome development in both Arabidopsis and cucumber33. EXO70E2 has been implicated in distinctive exocytotic organelles, namely EXPO, which mediate cytosol to cell wall exocytosis34. Among the EXO70 paralogs, EXO70A1 has been well characterized. EXO70A1 is expressed in most tissues, except for mature pollen28,35,36,37,38,39. EXO70A1 has been implicated in a wide range of developmental processes, including elongation of hypocotyls, formation of stigmatic papillae, polarized secretion in elongating root hairs28,40, pollen-stigma interaction during self-incompatibility response41, cell plate formation42, pectin deposition during seed coats development36 and auxin polar transport in root epidermal and cortical cells43. Recent studies have shown that EXO70A1 is primarily expressed in TEs and regulate vesicle trafficking during TE differentiation to mediate patterned secondary cell wall thickening in Arabidopsis thaliana37. Therefore, EXO70A1 is an essential subunit for exocytosis and is required for proper cell wall development in Arabidopsis. However, no EXO70 homologs in rice have been reported and thus its functions remain unclear. In this study, we identified the rice RLS2 gene that encodes OsEXO70A1, a key subunit of exocysts. Mutation in the rls2 causes irregular vascular bundles, abnormal SCW thickening in TEs and perturbs the assimilation of primary nutrients. Primary nutrient transporter or channel gene expression were tissue-specifically regulated in rls2 mutants, thus suggesting the possibility that RLS2-mediated vesicle trafficking is responsible for the translocation of integral membrane proteins to specific destinations. In sum, the present study has revealed that RLS2 is essential for vascular bundle differentiation and mineral nutrient assimilation and provides information on the functional complexity of exocysts in rice.

Results

The rls2 mutant shows pleiotropic defects

We obtained the mutant rapid leaf senescence 2 (rls2) by phenotypic screening of an ethyl methane sulfonate (EMS)-induced rice mutant collection in an indica cultivar. The rls2 mutant showed pleiotropic phenotypes and its most striking abnormality was the ferruginous necrotic spots on fresh leaves, which subsequently intensified and finally led to a dessicated appearance in mature leaves (Fig. 1a,b). In addition to necrotic leaves, rls2 plants exhibited dwarfism throughout its growth and development. Fifteen-day-old seedlings of rls2 mutants showed reduced height, but no distinct abnormalities were observed in its roots (Fig. S1). At the mature stage, a maximum disparity in plant height was observed between the rls2 mutant and wild-type plants (Fig. 1a and S1). The reduced height resulted from uniformly shortened internodes in the mutant culms, which were confirmed by comparison of the length of each internode between the mutant and wild-type (Fig. S1). Significant alterations were also observed in other agronomic traits such as panicle length, 1,000-grain weight and stem diameters (Fig. 1c–l). In sum, the rls2 mutants present necrotic leaves and overall growth abnormalities. We later acquired an allelic mutant line from the National Center of Plant Gene Research (Wuhan), in which RLS2 expression was downregulated by T-DNA insertion into the 3’-untranslated region (3’-UTR) (see below). Therefore, these two mutant lines were named rls2-1 and rls2-2, respectively. We primarily focused on the rls2-1 mutant line in the subsequent experiments.

Phenotypes of field-grown wild-type (WT) and rls2-1 mutant plants.

(a–f) Performance of whole plants (a), leaf with ferruginous spotted necrosis (b), panicle length (c), width and length of brown rice (d), I-IK staining pollens in WT and rls2-1 mutant plants (e,f). (a,b) grown in the field for 90 days. Bars = 25 cm in (a), 1 cm in (b), 5 cm in (c), 10 mm in (d), 40 μm in (e,f). (g–l) Agronomic traits (plant height, panicle length, productive panicle, fertility, 1,000-seed weight and stem diameter) of WT (black bars) and rls2-1 mutant (gray bars) plants. Error bars indicate SD (n = 15). p values determined by student’s t-test using R498 as control, ***p ≤ 0.001.

The rls2-1 mutant showing reduced hydraulic conductance and disruptions in primary nutrient assimilation

Mutant plants showed ferruginous necrotic spots in fresh leaves, which gradually became more severe, thus leading to dried and dead leaves (Fig. 1a,b and S1). A similar symptom could be caused by inefficient water transport, excessive transpiration and deficient mineral nutrient assimilation, particularly K+ deficiency. To address whether hydraulic transport or transpiration rate was affected in rls2-1, we performed a bleeding sap collection experiment and calculated the rate of excised-leaf water loss. Incisions were made by hand by cutting around the basilar part of a secondary internode. Plastic bags filled with absorbent cotton were affixed at the top of the culm, with the wound surface embedded in cotton. By measuring the weight at regular increments, we found that the amount of bleeding sap that was collected from the rls2-1 mutant plants was much less than that collected from the wild-type (Fig. 2a), indicating that the rls2 mutation affected the hydraulic transportation efficiency of stems. To ascertain whether the rls2-1 mutant affected water transpiration, we excised fresh leaves from rls2-1 and wild type plants at the pulvinus and weight losses were determined at different time points. No clear differences were detected, thereby indicating that rls2-1 mutants did not develop changes in transpiration rate (Fig. S2).

The mutation in the rls2-1 gene resulted in a reduction in hydraulic conductance and affected primary nutrient assimilation.

(a) The volume of bleeding sap collected from wild-type and rls2-1. Error bars indicate SD (n = 5). (b–d) Alterations in the concentration of primary nutrients in different tissues of wild-type and rls2-1 mutant plants, N(b), Pi(c), K+ (d). Error bars indicate SD (n = 5). Asterisks indicate significant differences between wild-type and rls2-1 mutant plants as determined by student’s t-test analysis: ***p ≤ 0.001, **p ≤ 0.01, *p ≤ 0.05.

Analysis of the primary nutrients in rls2-1 and wild type plants detected changes in the levels of N, Pi and K+ in rls2-1 mutant plants in an organ-specific way. N levels were distinctively higher in the roots, stems, leaf sheaths and young leaves of rls2-1 mutant plants compared to those in wild-type plants, but were similar to that in old leaf tissues (Fig. 2b). A similar concentration pattern for Pi accumulation was observed, except that there were no dissimilarities in young leaf tissues (Fig. 2c). Despite the elevated levels in the roots, stems and leaf sheath tissues (Fig. 2d), K+ levels dramatically decreased in leaf tissues, regardless of age or maturity (Fig. 2d). These results suggested that the rls2 mutation affected the assimilation of primary nutrients that involves a more complex mechanism.

Ultrastructural analyses of rls2-1 mutants

To characterize the anatomical defects of rls2-1 mutants, we performed semi-thin section analysis of its 2nd internode of the rls2-1mutant. We found that the vascular bundles were smaller in rls2-1 compared to that in the wild-type (Fig. S3a,b). The rls2-1 mutants and wild-type plants were then compared in terms of cell width and length, which in turn contributes to the thickness and length of each internode, respectively. The width and length of the cells in the 2nd internode of rls2-1 mutants were only 59% and 82% of that in the wild-type, respectively (Fig. S3c,d). These results indicated that reduced width and length of cells at the 2nd internode were related to thinner and shorter internodes in the rls2-1 mutants.

To assess ultrastructural alterations in rls2-1, we compared the chloroplast cells in the leaves, as well as vessel elements in the roots between the rls2-1 mutants and the wild-type plants by using transmission electron microscopy. Figure 3e–h shows no clear organelle structural alterations, except for abundant vesicle body accumulation (indicated by white arrowheads) in the rls2-1 mutants. We then observed the transection of leaves and nodes via scanning electron microscopy, which indicated that the vascular bundles of the leaves of rls2-1 mutants were smaller than those of the wild-type, with the volume of the xylem cavity significantly reduced (Fig. 3i,j). In mature nodes, the situation was more severe and the bundles were highly compact (Fig. 3k,l). These results demonstrated that the rls2 mutation led to narrower vascular bundle, which possibly compromised its function in water and nutrient transport.

Anatomical analysis of rls2-1 mutants.

(a–d) Semi-thin section analysis of the 2nd internodes of wild-type and rls2-1 mutant plants in cross (a,b) and longitudinal sections (c,d). (e–h) TEM comparison of chloroplast cells between the wild-type (e,g) and rls2-1 mutant plants (f,h). Large membrane-bound compartments were observed in mutant chloroplast cells as indicated by the asterisk. Bar = 3μm. (i–l) SEM observation of wild-type (I,k) and rls2-1 (j,l) vesicular bundle in leaf veins (i,j) and stems (k,l). Xylem and phloem are indicated by white and black arrows, respectively. Bar = 100 μm in (a–d,i,j) and 3 μm in (e–h) and 200 μm in (k,l).

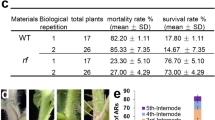

Map-based cloning of RLS2

To investigate the molecular basis underlying the observed alterations in rls2-1 mutants and to identify the causative gene responsible for this particular phenotype, we performed map-based cloning of the candidate gene. First, genetic analysis of the F2 population of the rls2-1 mutant and the wild-type (R498) plants revealed that the mutant necrotic leaf and dwarfism phenotypes were controlled by a single recessive nuclear locus (Table S1). Then, a mapping population was generated by crossing the rls2-1 mutant with Nipponbare, polymorphic japonica variety; a total of 1,912 homozygous mutant plants were isolated and used for mapping analysis. The candidate gene was roughly mapped between the polymorphic molecular markers RM6473 and RM17683 on chromosome 12 (Fig. 4a). Further fine mapping using newly designed adjacent INDEL markers (Table S2) narrowed down the location of the candidate gene to a 23-kb DNA region between markers I-6 and I-9, with three and two recombinants for the two markers, respectively (Fig. 4b). Based on annotations of the rice genome database, five putative open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted within this region (Table S3). Furthermore, a newly designed INDEL marker, I-8, was localized to one of these five ORFs, whereas none of recombinants were detected in I-8. Based on these observations, we presumed that the ORF of Os04g58880, which encodes EXO70A1, was the best candidate gene that was responsible for the phenotype observed in the RLS2 mutants. To test this hypothesis, we amplified and sequenced the ORF of Os04g58880 and found that a single nucleotide deletion in the seventh exon at nucleotide position 1,064, which is predicted to result in a frameshift mutation in rls2-1 (Fig. 4c). These findings suggested that Loc_Os04g58880 might be the candidate gene locus responsible for the mutant phenotypes and was thereby designated as RLS2.

Map-based cloning of the RLS2 gene.

(a) Preliminary and fine mapping of the RLS2 gene. The RLS2 locus was preliminarily mapped to rice chromosome 4 (Chr 4) between markers RM3310 and RM17689. Then, the gene was further localized to a 23-kb genomic region between markers I-6 and I-9. cM, centiMorgan. (b) RLS2 gene structure (upper panel). Gray shading, untranslated region; black shading, ORF region; Right angle, the site of single-base deletion mutation in rls2-1; triangle, the T-DNA insertion site of rls2-2. (c) Single-base deletion causes termination of translation in the rls2-1 mutant. (d) Allelic mutant rls2-2 exhibited similar but partially alleviated phenotype. Bar = 25cm.

To further confirm that the mutation in Loc_Os04g58880 corresponded to the rls2 locus, we introduced a wild-type genomic DNA fragment containing Loc_Os04g58880 into the rls2-1 mutant to determine whether wild-type Loc_Os04g58880 locus could complement the defective rls2-1 phenotype. However, no positive transgenic plants were generated, possibly due to the low efficiency in genetic transformation of the indica genetic background of rls2-1. Interestingly, we obtained a loss-of-function allelic mutant line from RMD mutant libraries44, in which a T-DNA fragment was inserted into the 3’UTR that partially affected transcription (Fig. 4d, Fig. S4) and we named it rls2-2. The rls2-2 mutants also exhibited necrotic leaves with ferruginous spots, short plant height and lower tiller number, similar to observed in the rls2-1 mutants (Fig. S4). Taken together, these results indicated that Loc_Os04g58880 encodes the RLS2 gene.

RLS2 is widely expressed in most tissues and preferentially in differentiated vascular bundles

To investigate the mRNA expression profile of RLS2, total RNA was extracted from the roots, culms, leaf blades, leaf sheaths and inflorescences at different developmental stages. cDNAs were synthesized by reverse transcription and the expression levels were determined by real-time PCR analysis. The results showed that RLS2 mRNA was ubiquitously expressed in most tissues, with highest level in leaves at the booting stage, followed by the spikelets; lower levels were detected in young roots, panicles and stems (Fig. 5a). Then, we investigated whether RLS2 was equably expressed in leaves. To answer this question, we assessed the mRNA expression of RLS2 using different parts of the leaves. Lower expression levels were detected in young leaves, which were encapsulated by the leaf sheath and white in color (Fig. 5b) and a successive increase in expression was observed from the base to the tip of the leaves (Fig. 5b). To more precisely investigate the spatial expression pattern of RLS2, we performed RNA in situ hybridization using stem sections from wild-type plants. RLS2 expression was detected predominantly in the stem vascular bundles (Fig. 5c,d). Together, these results indicated that RLS2 was constitutively expressed in all tissues and was spatially restricted in vascular bundles, which in turn suggested that it might be involved in vascular morphogenesis.

RLS2 expression profiling and protein subcellular localization.

(a,b) RT-PCR analysis of RLS2 expression (R, seedling root; L1-L5, seedling stage, tilling stage, booting stage, heading stage and filling stage leaves, respectively; YP1–YP8, 1 cm, 2 cm, 4 cm, 6 cm and 8 cm young panicles, respectively; H1–H5, 1 mm, 3 mm, 5 mm, 6 mm and 7 mm spikelets, respectively; S1–S2, tilling stage and heading stage internodes); YL, Young leaves, TL, Tip part of leaves; ML, middle part of leaves; and BL, base part of leaves. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). (c,d) RNA in situ hybridization detection of RLS2 expression in internode, antisense probe (c); sense probe (d), Scare bar = 200 μm. (e,f) Subcellular localization of OsRLS2. Transient expression of OsRLS2-GFP recombinant protein (e) and GFP protein (f) in rice protoplast cells. Scale bar = 20 μm.

To determine the subcellular location of RLS2, we prepared green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged construct of RLS2 and transiently expressed in rice protoplasts under the control of the 35S promoter. Punctate fluorescent signals located both on the PM and within the nucleus were observed by confocal microscopy at 16 h post-transformation (Fig. 5e). The protoplasts transformed with the empty GFP vector as control showed green fluorescent signals that were randomly distributed across the entire cell (Fig. 5f). These results suggested that the fusion protein was localized in both PM and nuclear regions.

rls2-1 mutants show irregular TE development and SCW deposition

Expression profiling revealed that the expression of RLS2 was spatially restricted to vascular bundles and anatomic observation showed vestigial vascular bundles in the leaves and stems of rls2-1 mutant plants. We thus presumed that RLS2 was responsible for TE formation in vascular bundles. To verify this hypothesis, we further examined the development of TEs in rls2-1 mutants using propidium iodide-stained root samples. Confocal microscopy revealed irregular pit patterns in rls2-1 plants compared to that of wild-type plants, which presented vessel cells with well-organized pits (Fig. 6a,b). The TEs of wild-type plants were indented or deeply lacerated, whereas that of the rls2-1 mutants appeared smooth. The perforations between two adjacent TEs in the rls2-1 mutants were narrower than those in the wild-type (Fig. 6a,b, indicated by white arrowheads), with a structural barrier existing at the site of the perforations, which could possibly hamper the transport of materials across the plant.

Defective TE formation in rls2-1 mutant plants.

(a,b) Mature metaxylem from wild-type (a) and rls2-1 mutant (b) roots were stained with propidium iodide and observed under a confocal microscope. Note that pits were irregular and the perforation between two adjacent TEs in rls2-1 was incomplete, as indicated by white arrowheads. Bar = 10 μm. (c,d) TEM images of longitudinally sectioned mature xylem in wild-type (c) and rls2-1 (d) roots. Note the irregular SCW deposition (black arrowheads) on the inner side of TEs in the rls2-1 mutant plants. Bars = 2.5 μm. (e,f) The contents of cellulose (e) and lignin (f) clearly decreased in the rls2-1 mutant plant. Error bars indicate SD (n = 5). Asterisks indicate significant differences between wild-type and rls2-1 mutant plants as determined by student’s t-test analysis: ***p ≤ 0.001.

Subsequently, we examined ultrathin sections of the root elongation zone of the mutant and wild-type plants by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), which showed that TE differentiation and secondary cell wall (SCW) deposition were active. Instead of the regularly patterned SCW thickening in the wild-type plants (Fig. 6c), larger-sized SCW thickening within mature TEs were observed in the rls2-1 mutants (Fig. 6d, indicated by black arrowheads). Interestingly, SCW thickening occurred on both sides of the TE PM and formed ribosome-like structures in the wild-type, whereas SCW thickening was only deposited on the inner side of the TE PM (Fig. 6d, indicated by a black arrowhead), which was consistent with the discovery that TEs exhibited a smooth surface in rls2-1 mutants. The above results demonstrated that RLS2 is essential for TE differentiation and SCW deposition.

Next, to examine whether the mutation of rls2 generally caused comprehensive irregular SCW deposition, we evaluated the cellulose and lignin content of mature 2nd internodes from the wild-type and rls2-1 mutant plants. The cellulose and lignin content of rls2-1 mutant internodes were predominantly higher than that observed in the wild-type (Fig. 6e,f).

The genes involved in primary nutrients uptake and transport are regulated in a tissue-specific manner in rls2-1 mutants

The mechanism of absorption, transportation and assimilation of three primary nutrients have been well studied in both Arabidopsis and rice1,2,3,4,5,6,7, which in turn has allowed us to verify whether tissue-specific regulation of primary nutrient accumulation was associated with the altered expression of Pi, N and K+ transporters or channels in the rls2-1 mutants. The expression levels of four members of rice high-affinity phosphate transporters (OsPT1, OsPT4, OsPT6 and OsPT8)45, one nitrate transporter (OsNRT2.1), two ammonia transporters (OsAMT1.1 and OsAMT1.3)11,46,47 and eight K+ transporters or channels (OsAK1, OsAM1, OsHAK1, OsHAK4, OsHAK5, OsHAK10, OsTPKa and OsTPKb)4,5,6,7 were examined by qRT-PCR analysis in the wild-type and rls2-1 mutant plants. Consistent with the observation that the Pi and N contents were distinctively higher in stems, leaf sheaths and leaf tissues of the rls2-1 mutants (Fig. 2b,c), the genes responsible for the uptake and transport of Pi and N were predominantly upregulated in aerial tissues of the rls2-1 mutants (Fig. 7a–g).

Gene expression analysis of genes involved in primary nutrient uptake, transport in wild-type and rls2-1 mutant plants.

Expression analysis of OsPT1 (a), OsPT4 (b), OsPT6 (c) and OsPT8 (d); OsATM.1 (e), OsATM.3 (f) and OsNTR2.1 (g); OsAKT1 (h), OsAM1 (i) and OsHAK1 (j); OsHAK4 (k), OsHAK5 (l), OsHAK10 (m), OsTPKa (n) and OsTPKb (o) at the stems, leaf sheaths and leaf tissues in the wild-type and rls2-1 mutant plants by RT-qPCR. OsActin1 was used as reference for normalization. Error bars show the SD (n = 3). S, stem tissue; LS, leaf sheath tissue; L, leaf tissue. Significant differences between wild-type and rls2-1 mutant plants were determined by using the student’s t-test: ***p ≤ 0.001, **p ≤ 0.01, *p ≤ 0.05.

K+ levels simultaneously increased in the stem and leaf sheath tissues of the rls2-1 mutant plants (Fig. 2d). Furthermore, the corresponding genes involved in K+ uptake and long-distance transport that encoded PM-specific proteins were upregulated in the stem and leaf sheath tissues of the rls2-1 mutants (Fig. 7l–q). K+ deficiency was detected in the young leaf tissues of the rls2-1 mutant plants (Fig. 2d) and qRT-PCR analysis revealed that the transcriptional level of tonoplast-located K+ channel (TPKs) was significantly reduced in the leaf tissues of the rls2-1 mutants (Fig. 7h–m). On the other hand, no detectable discrepancies in transcript accumulation or downregulation of PM-located K+ transporters or channels were observed (Fig. 7n,o). These results demonstrated that the expression of K+ transporters or channels was regulated by RLS2 in a highly specific manner.

Expression analysis of EXO70A1 orthologous genes

The Arabidopsis and rice genomes encode 23 and 47 EXO70 genes, respectively, which are then further grouped into nine clusters28,32. EXO70A1, EXO70D2 and EXO70H7 appear to be constitutively expressed in Arabidopsis. Because of the absence of data on the expression and functional analyses of EXO70 genes in rice, we resorted to using the Rice Expression Profile Database (RiceXPro) (http://ricexpro.dna.affrc.go.jp), which has revealed that the expression of four OsEXO70 genes, namely, OsEXO70F1, OsEXO70FX13 (monocot-specific Exo70s), OsEXO70F3. and OsEXO70D1, were widely interwoven with the RLS2 protein. Three additional isoforms were also detected in the EXO70A cluster, which included OsEXO70A2 (Os04g58870), OsEXO70A3 (Os11g05880) and OsEXO70A4 (Os12g06270). To investigate whether the mutation in the rls2 gene results in changes in the transcriptional patterns of these orthologous genes in vivo, qRT–PCR was performed using total RNA isolated from the culms and leaves of rls2-1 and wild-type plants. The expression levels of the OsEXO70F3, OsEXO70FX13, OsEXO70D1 and OsEXO70A4 genes were markedly higher in the rls2-1 stems (Fig. 8b–d,f). Enhanced expression levels of OsEXO70FX13 and OsEXO70A3 genes were also observed in the rls2-1 leaves (Fig. 8c,e), whereas OsEXO70F1 and OsEXO70A3 significantly decreased in rls2-1 stems (Fig. 8a,e). Taken together, these results revealed that the mutation in the rls2 gene affected the expression of multiple orthologous OsEXO70 genes in vivo.

The mutation in the rls2 genes causes transcriptional fluctuations in orthologous genes in vivo.

(a–f) Gene expression analysis for OsEXO70 genes in wild-type and rls2-1 mutant plants. Expression analysis of OsEXO70F1 (a), OsEXO70F3 (b), OsEXO70FX13 (c), OsEXO70D1 (d), OsEXO70A3 (e), OsEXO70A4 (f) in the stems and leaves of wild-type (R498) and rls2-1 mutant plants by RT-qPCR. OsActin1 was used as reference for normalization. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). S, stem tissue; L, leaf tissue. Significant differences between wild-type and rls2-1 mutant plants were determined by using the student’s t-test and indicated by asterisks: *p ≤ 0.05.

Discussion

Previous phylogenetic analysis of EXO70 protein sequences has indicated that angiosperm EXO70s could be grouped into three subfamilies and nine clusters32, of which the EXO70.1 proteins (including the angiosperm EXO70A cluster) are considered as the best candidates for genuine exocyst subunits. Among the mutants in this gene family, only T-DNA insertions in the EXO70A1 gene result in a discernible phenotype in Arabidopsis28. The exo70a1-1 mutants exhibit indeterminate highly branched inflorescence and delayed senescence and exo70a1-1 seedlings exhibit a higher percentage of branched root hairs when grown in liquid culture medium28. Even though a higher number of EXO70 genes are encoded in rice, functional loss of RLS2 could not fully be compensated by other paralogs. Similarly, we observed pleiotropic defects, including dwarfism, lower tiller number and abnormal tracheary element differentiation (Figs 1a and 4a–d). Unlike the exo70a1 mutant in Arabidopsis, the rls2-1 mutant showed early senescence of leaves and normal root morphology (Fig. 1a and S1). These results indicated that compared to Arabidopsis EXO70A1, RLS2 possesses a highly conserved and distinct function in rice.

Previous studies have revealed that cortical microtubules and the actin cytoskeleton play essential roles in the trafficking of vesicles that carry various kinds of protein complexes and materials to the PM, where the secondary wall was deposited48. It has been proposed that the EXO70A1 gene functions in vesicle trafficking during vessel differentiation37. The present study determined that rls2-1 mutants possessed vessel cells with thicker ectopic SCW and significantly higher cellulose and lignin levels (Fig. 4c,d). In addition, we have determined that some EXO70 orthologous genes were differentially expressed in rls2-1 mutants. The expression of OsEXO70F3, OsEXO70FX13, OsEXO70D1, and OsEXO70A4 genes markedly increased in rls2-1 stems (Fig. 8a–f). Based on these findings, we hereby propose two hypotheses that could potentially explain the observed thickening of the SCW in rls2-1 mutants. (1) Vesicle trafficking not only carries the CesA synthesis complex and hemicellulose that are utilized in cell wall formation, but also transports cellulase and hemicellulase that are essential for cell wall remodeling during the cell extension stage49,50. These processes are facilitated by EXO70A1, which is supported by the fact that cell size in transverse and longitudinal directions significantly decreased in the mutants (Fig. 3a–d and S3). (2) The EXO70 subunit facilitates plant cell-specific exocyst formation and potentially functional divergence28,29. The increased expression of EXO70 orthologous genes in the stems of rls2-1 mutants possibly induces the assembly of a distinct exocyst complex, which in turn disrupts normal SCW deposition, thereby causing disorders in vesicle trafficking.

Most importantly, we found that the mutation in the rls2 gene affects the assimilation of primary nutrients. N, Pi and K+ levels were regulated in a tissue-specific manner in the rls2-1 mutants (Fig. 2b–d). Therefore, the excessive accumulations of N, Pi and K+ in the roots and leaf sheath tissues resulted in rls2-1 lethality. Young leaves showed severe K+ deficiency, which is the main cause of ferruginous necrotic spots in rls2 mutants. We were not convinced that most of the defects observed in the exo70a1-1 mutant could be simply explained by imperfect TEs in Arabidopsis37.

In the Pi signaling pathway, ubiquitination mediated by PHO2 (E2 and LTN1 in rice) and NLA (E3) play key roles in the removal of proteins from the PM via the endocytic pathway51. The ubiquitination of PHT1s in post-ER compartments is mediated by PHO2, whereas NLA-dependent ubiquitination is required for clathrin-dependent endocytosis of the PM-localized PHT1s8,9,52. The fact that neither PHO2 nor NLA have been predicted to have any transmembrane domain or post-translational lipid modification raises questions about the mechanism underlying its recruitment to the PM. We found that the high-affinity transporters of Pi and N are uniformly upregulated in rls2-1 mutants (Fig. 7a–g), which in turn may lead to the accumulation of Pi and N in various plant tissues. These results suggest that exocysts are involved in membrane-associated ubiquitin machinery, by which PHO2 and NLA are recruited to the PM. Pi and N high-affinity transporters are usually located in the PM, whereas K+ transporters or channels are found not only in the PM, but also in other membrane systems5,7,15. In particular, the tonoplast-located K+ channels are necessary for maintaining cellular electroneutrality and osmotic equilibrium5. However, little is known about the mechanistic details of how integral membrane proteins arrive at its specific destinations. Here, TM-located K+ transporters (OsAK1, OsAM1, OsHAK1, OsHAK4, OsHAK5 and OsHAK10) and tonoplast-located K+ channels (TPKa and TPKb) were discriminatively regulated in rls2-1 mutants (Fig. 7h–o). The former were uniformly upregulated in the stems and leaf sheath tissues of the rls2-1 mutant plants, whereas these were minimally affected in leaf tissues (Fig. 7h–m). On the other hand, the latter were distinctively repressed in the leaf tissues of rls2-1 mutants and normally expressed in the other tissues (Fig. 7n,o). In summary, our results have revealed that RLS2-mediated vesicle trafficking could be involved in the distribution of tonoplast-located K+ to specific membrane destinations. However, further investigation is needed to be performed to understand the functional complexity of EXO70A1 in rice and Arabidopsis.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Rice (Oryza sativa) mutant rls2-1 was isolated from the indica cultivar EMS-mutated R498 population, an elite restorer line for hybrid rice. All plants were grown in paddy fields of the Rice Research Institute of Sichuan Agriculture University (China, Cheng Du) or Ling Shui (Hainan Province, China) during its natural growing season.

Measurement of primary nutrient concentrations

Samples from different tissues of the rls2-1 and wild-type plants were collected at the booting stage, rinsed with deionized water and dried at 80 °C to constant weight in paper bags. The dry weights of the samples were measured as dry biomass. For the measurement of total P concentration, ~0.05-g of the dry samples was used following in the method described elsewhere53. N concentration was measured using a colorimetric method45. K+ content analysis was conducted as previously described6.

Bleeding sap collection and rate of water loss in excised leaves

Bleeding sap collections were performed as described elsewhere54. Generally, bleeding sap collection was performed on plants grown in the paddy fields; it involved the 12-h direct collection of sap from a stem that was cut off 9–10 cm above the soil surface into the provided cotton. The bleeding sap volume was calculated from the weight increase of the cotton. For the excised-leaf water loss rate and fresh flag leaves of main tillers were excised from rls2-1 and wild-type plants at the position of the pulvinus. Leaf area was measured by using a living leaf area meter (YMJ-B). Weight loss was recorded at distinct time points. The excised-leaf water rate was calculated based on the weight loss at each time point versus leaf area.

Anatomical analyses

To evaluate cell anatomical features of the plants, fresh hand-cut sections (approximately 20 μm) of the 2nd internode of culms and 2nd leaves were prepared and stained with toluidine blue and examined under a light microscope (Leica).

SEM was used as previously described55; samples at different stages were pre-fixed in a 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde (pH 6.8) overnight at 4 °C, then rinsed twice with 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.8). The samples were dehydrated using an acetone series of increasing gradations from 30% to 100% and then exchanged three times with isoamyl acetate. The fixed samples were processed for critical-point drying using liquid CO2 and then gold coated. The samples were examined under a JEM-1200 EX scanning electron microscope (Hitachi).

For TEM, samples from leaves, stems and roots of rls2-1 plants and wild-type plants were collected. The tissues were prefixed in 3% glutaraldehyde and then fixed in a 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer containing 2% osmium tetroxide for at least overnight at 4 °C. The tissues were then dehydrated in an acetone series, infiltrated in Epox 812 for 4 h and embedded. Ultrathin sections were cut with a diamond knife and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Sections were examined under a transmission electron microscope (HITACHI, H-600IV, Japan).

Map-based cloning of RLS2

The rls2-1 mutants were crossed with Nipponbare, a polymorphic japonica variety that has been widely used for map-based cloning. In the F2 progeny, plants showing necrotic spotted leaves and dwarfism were selected for gene linkage analysis. Preliminary mapping was performed with molecular markers distributed across the 12 rice chromosomes. Fine-mapping sequence-tagged site primers were designed according to the different DNA sequences of indica and japonica (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Primers used in fine mapping are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR were performed as previously described56. mRNA was extracted from the collected tissue samples using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). About 1000 ng of total RNA was treated with DNaseI and used in first-strand cDNA synthesis with oligo(dT)18 as primer. SuperScript II (Invitrogen, USA) was used as the reverse transcription enzyme. The qRT-PCR was run on CFX96™ Real-Time System (Bio-Rad, USA) with gene-specific primers. The reaction was performed at 95 °C for 1 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s. The sequences of the primers used are listed in Table S2. Rice ACTIN1 was used as internal control in all analyses. The ΔΔCq method of the CFX Manager™ software version 3.0 (Bio-Rad, USA) was used to normalize gene expression. Three replicates were performed for each gene.

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridizations were performed as described elsewhere55, with minor modifications. To generate RLS2-specific sense and antisense probes, a 455-bp fragment at the 3’-UTR of the full-length cDNA was amplified from wild-type cDNA using RLS2-specific primers, both at the 3’-end and 5’-end, of which a T7 promoter binding sequence (TAACTAATACGACTCACTATAGGG) was added and then transcribed with a T7 RNA polymerase. The primers are listed in Table S2.

Subcellular localization

Rice protoplasts were isolated from Nipponbare seedlings and were transformed with the recombinant plasmids pC2300-RLS2 and pC2300 alone as described elsewhere57. Fluorescence was examined under confocal microscopy (Nikon A1 i90, LSCM, Japan) at 16 h post-transformation.

Measurement of cellulose and lignin levels

The 2nd internode tissues of rls2-1 and wild-type plants were collected at the filling stage, rinsed with deionized water, heated at 105 °C for 0.5 hour and then dried at 80 °C to constant weight in paper bags. The dried samples were fully ground and passed through an 80-mesh size seize. The measurement of cellulose and lignin were performed using FibertecTM M6 1020 (FOSS).

Plasmid construction

For the construction of the pACTIN::RLS2-GFP plasmid, cDNA (without the stop codon) was PCR amplified using primers RLS2-CDSF and RLS2-CDSR and inserted to into plasmid PC2300-Actin (35S promoter was replaced by an actin promoter) at the KpnI and SalI sites. The plasmid was used to transform a Kitaake callus with Agrobacterium (EHA105). The genetic transformation of rice was performed as described by Cheng58. After selection for G418 resistance, the regenerated plants were confirmed by PCR-based genotyping using a primer pair specific for the Npt II gene (Table S2).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the Excel software (Microsoft) for average values, SD and student’s t-test analyses.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Tu, B. et al. Disruption of OsEXO70A1 Causes Irregular Vascular Bundles and Perturbs Mineral Nutrient Assimilation in Rice. Sci. Rep. 5, 18609; doi: 10.1038/srep18609 (2015).

References

Chiou, T. J. et al. Regulation of phosphate homeostasis by MicroRNA in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18, 412–21 (2006).

Lin, S. I. et al. Regulatory network of microRNA399 and PHO2 by systemic signaling. Plant Physiol 147, 732–46 (2008).

Krapp, A. Plant nitrogen assimilation and its regulation: a complex puzzle with missing pieces. Curr Opin Plant Biol 25, 115–22 (2015).

Banuelos, M. A., Garciadeblas, B., Cubero, B. & Rodriguez-Navarro, A. Inventory and functional characterization of the HAK potassium transporters of rice. Plant Physiol 130, 784–95 (2002).

Isayenkov, S., Isner, J. C. & Maathuis, F. J. M. Rice Two-Pore K+ Channels Are Expressed in Different Types of Vacuoles. Plant Cell 23, 756–768 (2011).

Li, J. et al. The Os-AKT1 channel is critical for K+ uptake in rice roots and is modulated by the rice CBL1-CIPK23 complex. Plant Cell 26, 3387–402 (2014).

Yang, T. et al. The role of a potassium transporter OsHAK5 in potassium acquisition and transport from roots to shoots in rice at low potassium supply levels. Plant Physiol 166, 945–59 (2014).

Huang, T. K. et al. Identification of downstream components of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme PHOSPHATE2 by quantitative membrane proteomics in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 25, 4044–60 (2013).

Lin, W. Y., Huang, T. K. & Chiou, T. J. Nitrogen limitation adaptation, a target of microRNA827, mediates degradation of plasma membrane-localized phosphate transporters to maintain phosphate homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25, 4061–74 (2013).

Fujii, H., Chiou, T. J., Lin, S. I., Aung, K. & Zhu, J. K. A miRNA involved in phosphate-starvation response in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 15, 2038–43 (2005).

Yan, M. et al. Rice OsNAR2.1 interacts with OsNRT2.1, OsNRT2.2 and OsNRT2.3a nitrate transporters to provide uptake over high and low concentration ranges. Plant Cell Environ 34, 1360–72 (2011).

Tang, Z. et al. Knockdown of a rice stelar nitrate transporter alters long-distance translocation but not root influx. Plant Physiol 160, 2052–63 (2012).

Ranathunge, K., El-Kereamy, A., Gidda, S., Bi, Y. M. & Rothstein, S. J. AMT1;1 transgenic rice plants with enhanced NH4(+) permeability show superior growth and higher yield under optimal and suboptimal NH4(+) conditions. J Exp Bot 65, 965–79 (2014).

Bao, A., Liang, Z., Zhao, Z. & Cai, H. Overexpressing of OsAMT1-3, a High Affinity Ammonium Transporter Gene, Modifies Rice Growth and Carbon-Nitrogen Metabolic Status. Int J Mol Sci 16, 9037–63 (2015).

Sheng, P. et al. Albino midrib 1, encoding a putative potassium efflux antiporter, affects chloroplast development and drought tolerance in rice. Plant Cell Rep 33, 1581–94 (2014).

Lucas, W. J. et al. The plant vascular system: evolution, development and functions. J Integr Plant Biol 55, 294–388 (2013).

Baskin, T. I. On the alignment of cellulose microfibrils by cortical microtubules: a review and a model. Protoplasma 215, 150–71 (2001).

Paredez, A. R., Somerville, C. R. & Ehrhardt, D. W. Visualization of cellulose synthase demonstrates functional association with microtubules. Science 312, 1491–5 (2006).

Zhong, R., Burk, D. H., Morrison, W. H. 3rd & Ye, Z. H. A kinesin-like protein is essential for oriented deposition of cellulose microfibrils and cell wall strength. Plant Cell 14, 3101–17 (2002).

Burk, D. H. & Ye, Z. H. Alteration of oriented deposition of cellulose microfibrils by mutation of a katanin-like microtubule-severing protein. Plant Cell 14, 2145–60 (2002).

Wightman, R. & Turner, S. R. The roles of the cytoskeleton during cellulose deposition at the secondary cell wall. Plant J 54, 794–805 (2008).

Zhong, R. & Ye, Z. H. Secondary cell walls: biosynthesis, patterned deposition and transcriptional regulation. Plant Cell Physiol 56, 195–214 (2015).

Synek, L., Sekeres, J. & Zarsky, V. The exocyst at the interface between cytoskeleton and membranes in eukaryotic cells. Front Plant Sci 4, 543 (2014).

He, B. & Guo, W. The exocyst complex in polarized exocytosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol 21, 537–42 (2009).

Elias, M. et al. The exocyst complex in plants. Cell Biol Int 27, 199–201 (2003).

Chong, Y. T. et al. Characterization of the Arabidopsis thaliana exocyst complex gene families by phylogenetic, expression profiling and subcellular localization studies. New Phytol 185, 401–19 (2010).

Hala, M. et al. An exocyst complex functions in plant cell growth in Arabidopsis and tobacco. Plant Cell 20, 1330–45 (2008).

Synek, L. et al. AtEXO70A1, a member of a family of putative exocyst subunits specifically expanded in land plants, is important for polar growth and plant development. Plant J 48, 54–72 (2006).

Cvrckova, F. et al. Evolution of the land plant exocyst complexes. Front Plant Sci 3, 159 (2012).

Pecenkova, T. et al. The role for the exocyst complex subunits Exo70B2 and Exo70H1 in the plant-pathogen interaction. J Exp Bot 62, 2107–16 (2011).

Stegmann, M. et al. The ubiquitin ligase PUB22 targets a subunit of the exocyst complex required for PAMP-triggered responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24, 4703–16 (2012).

Li, S. et al. Expression and functional analyses of EXO70 genes in Arabidopsis implicate their roles in regulating cell type-specific exocytosis. Plant Physiol 154, 1819–30 (2010).

Kulich, I. et al. Cell wall maturation of Arabidopsis trichomes is dependent on exocyst subunit EXO70H4 and involves callose deposition. Plant Physiol 168, 120–31 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. EXPO, an exocyst-positive organelle distinct from multivesicular endosomes and autophagosomes, mediates cytosol to cell wall exocytosis in Arabidopsis and tobacco cells. Plant Cell 22, 4009–30 (2010).

Jia, Y., Xing-guo, L., Ai-xin, H. & Yu-hua, A. L. Isolation and Expression Analysis of Exo70A1 of Ornamental Kale. Acta Horticulturae Sinica 39, 127–135 (2012).

Kulich, I. et al. Arabidopsis exocyst subunits SEC8 and EXO70A1 and exocyst interactor ROH1 are involved in the localized deposition of seed coat pectin. New Phytol 188, 615–25 (2010).

Li, S. et al. EXO70A1-mediated vesicle trafficking is critical for tracheary element development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25, 1774–86 (2013).

Safavian, D. et al. High humidity partially rescues the Arabidopsis thaliana exo70A1 stigmatic defect for accepting compatible pollen. Plant Reprod 27, 121–7 (2014).

Wang, L. et al. Molecular Cloning, Expression Analysis and Localization of Exo70A1 Related to Self Incompatibility in Non-Heading Chinese Cabbage (Brassica campestris ssp. chinensis). Journal of Integrative Agriculture 12, 2149–2156 (2013).

Wen, T. J., Hochholdinger, F., Sauer, M., Bruce, W. & Schnable, P. S. The roothairless1 gene of maize encodes a homolog of sec3, which is involved in polar exocytosis. Plant Physiol 138, 1637–43 (2005).

Samuel, M. A. et al. Cellular pathways regulating responses to compatible and self-incompatible pollen in Brassica and Arabidopsis stigmas intersect at Exo70A1, a putative component of the exocyst complex. Plant Cell 21, 2655–71 (2009).

Fendrych, M. et al. The Arabidopsis exocyst complex is involved in cytokinesis and cell plate maturation. Plant Cell 22, 3053–65 (2010).

Drdova, E. J. et al. The exocyst complex contributes to PIN auxin efflux carrier recycling and polar auxin transport in Arabidopsis. Plant J 73, 709–19 (2013).

Zhang, J. et al. RMD: a rice mutant database for functional analysis of the rice genome. Nucleic Acids Res 34, D745–8 (2006).

Hu, B. et al. LEAF TIP NECROSIS1 plays a pivotal role in the regulation of multiple phosphate starvation responses in rice. Plant Physiol 156, 1101–15 (2011).

Sonoda, Y. et al. Distinct expression and function of three ammonium transporter genes (OsAMT1;1-1;3) in rice. Plant Cell Physiol 44, 726–34 (2003).

Yang, S., Hao, D., Cong, Y., Jin, M. & Su, Y. The rice OsAMT1;1 is a proton-independent feedback regulated ammonium transporter. Plant Cell Rep 34, 321–30 (2015).

Wightman, R. & Turner, S. R. The roles of the cytoskeleton during cellulose deposition at the secondary cell wall. The Plant Journal 54, 794–805 (2008).

Rennie, E. A. & Scheller, H. V. Xylan biosynthesis. Curr Opin Biotechnol 26, 100–7 (2014).

Altartouri, B. & Geitmann, A. Understanding plant cell morphogenesis requires real-time monitoring of cell wall polymers. Curr Opin Plant Biol 23c, 76–82 (2015).

MacGurn, J. A., Hsu, P. C. & Emr, S. D. Ubiquitin and membrane protein turnover: from cradle to grave. Annu Rev Biochem 81, 231–59 (2012).

Guerra, D. D. & Callis, J. Ubiquitin on the move: the ubiquitin modification system plays diverse roles in the regulation of endoplasmic reticulum- and plasma membrane-localized proteins. Plant Physiol 160, 56–64 (2012).

Wang, Z. et al. Regulation of OsSPX1 and OsSPX3 on expression of OsSPX domain genes and Pi-starvation signaling in rice. J Integr Plant Biol 51, 663–74 (2009).

Sakurai, J., Ishikawa, F., Yamaguchi, T., Uemura, M. & Maeshima, M. Identification of 33 rice aquaporin genes and analysis of their expression and function. Plant Cell Physiol 46, 1568–77 (2005).

Qin, P. et al. ABCG15 encodes an ABC transporter protein and is essential for post-meiotic anther and pollen exine development in rice. Plant Cell Physiol 54, 138–54 (2013).

Tu, B. et al. Distinct and Cooperative Activities of HESO1 and URT1 Nucleotidyl Transferases in MicroRNA Turnover in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet 11, e1005119 (2015).

Bart, R., Chern, M., Park, C.-J., Bartley, L. & Ronald, P. C. A novel system for gene silencing using siRNAs in rice leaf and stem-derived protoplasts. Plant methods 2, 13 (2006).

Cheng, X., Sardana, R. & Altosaar, I. Rice Transformation by Agrobacterium Infection. in Recombinant Proteins from Plants Vol. 3 (eds. Cunningham, C. & Porter, A. R. ) 1–9 (Humana Press, 1998).

Acknowledgements

The rls2-2 allelic mutant line was kindly provided by the National Center of Plant Gene Research (Wuhan) of Huazhong Agricultural University (Rice Mutant Database: http://rmd.ncpgr.cn/introduction.cgi?nickname=). We thank Professor Yungao Hu of SWUST (Southwest University of Science and Technology) for providing facilities and advice for cellulose and lignin analysis. We would like to thank Xuewei Chen of SCAU and Shengben Li of the Agricultural Genomics Institute at Shenzhen China Academy of Agricultural Sciences for editing and providing comments regarding this manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China [31471475,31571634].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.T., P.Q. and S.L. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. B.T. and S.Y. isolated the rls2-1 mutants and conducted agronomic character investigation. B.T., W.C. and L.H. performed mapping-based cloning of RLS2. B.T., L.H., T.L. and S.Y. performed the anatomical analyses. B.T., W.C. and B.H. performed expression analysis and subcellular localization assays. W.C. and Z.L. collected bleeding sap and analyzed the primary nutrients. B.T., L.Z. and L.H. performed Q-PCR analysis. Y.W., B.M. and X.C. provided advice on the experiments.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Tu, B., Hu, L., Chen, W. et al. Disruption of OsEXO70A1 Causes Irregular Vascular Bundles and Perturbs Mineral Nutrient Assimilation in Rice. Sci Rep 5, 18609 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18609

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18609

This article is cited by

-

Emerging roles of cortical microtubule–membrane interactions

Journal of Plant Research (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.