Abstract

The past decade has seen a number of interesting designs proposed and implemented togenerate artificial magnetism at optical frequencies using plasmonic metamaterials,but owing to the planar configurations of typically fabricated metamolecules thatmake up the metamaterials, the magnetic response is mainly driven by the electricfield of the incident electromagnetic wave. We recently fabricated verticalsplit-ring resonators (VSRRs) which behave as magnetic metamolecules sensitive toboth incident electric and magnetic fields with stronger induced magnetic dipolemoment upon excitation in comparison to planar SRRs. The fabrication techniqueenabled us to study the plasmon coupling between VSRRs that stand up side by sidewhere the coupling strength can be precisely controlled by varying the gap inbetween. The resulting wide tuning range of these resonance modes offers thepossibility of developing frequency selective functional devices such as sensors andfilters based on plasmon coupling with high sensitivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plasmonic metamaterials composed of artificial sub-wavelength structures typicallyinvolving metal have gained tremendous interest during the past decade because of theirextraordinary optical properties and potential applications1,2,3,4,5. These properties and applications of the metamaterials are intrinsicallyconnected to the localized surface plasmon (SP) resonances (LSPR) arising from thecollective oscillations of free electrons which induce strong electromagnetic fieldsadjacent to the artificial sub-wavelength metallic elements (referred to here asmetamolecules) in the metamaterials6,7. Properties ofmetamaterials can be readily tailored by engineering their constituent metamoleculescomposed of subwavelength metal structures8. For instance, ametamolecule constructed with a pair of closely spaced plasmonic elements exhibitsrather different optical response than those made of isolated ones9. The plasmonic coupling of metamolecules has been explored to achieve a numberof applications, such as the Fano resonance10,11, toroidal dipolarresponse12,13, Rabi splitting14,15 andbiosensors16. While these promising applications ofmetamaterials continue to extend beyond the reach of any conventional media, one cannothelp notice that most of them are driven by the electric field of an incidentelectromagnetic wave17. It is nevertheless desirable to expand theoptical properties of these metamaterials to include their responses to magnetic fieldas well. Magnetic coupling through mutual inductive effects has been studied in in-planecoupled split-ring resonators (SRRs)18,19,20,21,22, but thedipoles were still excited by the incident electric field in experiment. The fact that amajority of previous studies have mainly focused on the plasmonic properties in themetamaterials that are mostly derived from the dipole response to the electric field ofthe incident wave acting upon these metamaterials is the direct consequence ofsignificant technical challenges in the fabrication of metamaterials because they arefar more easily constructed with planar sub-wavelength elements on substrates23,24,25 and their magnetic dipole moments driven only by theelectric field of incident electromagnetic wave are always perpendicular to the magneticfield of a normal incident wave, resulting in a weak interaction with the magneticfield26,27,28. Attempts have been made to address this issuewith the use of multilayer metamaterials but the fabrication techniques are stillchallenging29,30,31,32. While the oblique incidence alsoallows for the magnetic response to be observed to a certain degree33,34, such an effect can be further enhanced with the fabrication of verticalsplit-ring resonator (VSRR) structures in which the metamolecules stand up vertically,leading to their magnetic dipoles that can not only be excited by the electric field,but also by the magnetic field directly under normal incidence35,36,37.

In this work, using a recently developed high precision alignment technique38, we have fabricated VSRRs which allowed us to study how incidentelectromagnetic fields interact with these VSRRs and to reveal the plasmon couplingbetween closely spaced VSRRs in dimer structures (metamolecules). We first numericallycompare the magnetic plasmon excitation between isolated SRRs that are in either planaror vertical configuration. We then fabricate and measure spectral transmittance ofisolated VSRRs to identify their magnetic resonance. Taking advantage of the flexibilityin arranging VSRRs that stand up side by side where the coupling strength of theirmagnetic dipoles can be tuned far more efficiently with their spacing, we have observedelectric and magnetic plasmon coupling of two VSRRs of different dimensions resulting ina range of resonance shift. The vertical configuration enable more densely packedmetamolecules for enhanced plasmonic properties.

Results

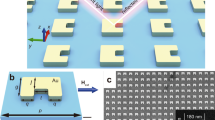

We have conducted numerical simulation using COMSOL to establish the comparisonbetween single isolated planar and VSRR metamolecules of equal dimensions (baselength L = 195 nm) as shown in Figs. 1a and1c, respectively, under the excitation of a normalincident wave with its electric field polarized along the SRR gap (x-axis). In thisconfiguration, planar SRRs are driven by the incident electric field only becausethe incident magnetic field is perpendicular to their magnetic dipoles which getinduced only because of the bianisotropy39,40, the VSRRs, onthe other hands, are excited by both electric and magnetic components of theincident wave and the effect of bianisotropy includes excitations of electric andmagnetic dipoles by magnetic and electric fields, respectively. Considering goldSRRs placed on a glass (BK7) substrate, we have simulated the magnetic response ofboth SRRs. For planar SRRs, the magnetic response is induced by the oscillatingelectric current in the SRR due to its interaction with the incident electric fieldand a distribution of magnetic energy density is present within the SRR openingbetween the prongs (Fig. 1b). In comparison, the VSRRstructure has a clear advantage in that it couples directly with not only theelectric field but also the magnetic field under normal illumination. Our simulationresult indicates that stronger magnetic energy density can indeed be obtained underthe same dimensions and illumination condition (Fig. 1d).

Field confinement and distribution in isolated SRR structures.

Schematic diagrams of planar (a) and vertical SRR (c) of identicaldimensions. Parameter L indicates the length of base rod (L =195 nm). The induced magnetic energy density in arbitrary unitunder normal incidence at plasmon resonance is shown in two perpendicularplanes for comparison. Observation planes are shown as insets in (b) and(d). The side views (left) in (b) and (d) are for the plane that is centeredalong the SRR bas rods, the top views (right) in (b) and (d) are for theplane inserted between the base rod and the two prongs. Arrows in magentaindicate the direction of the induced surface current.

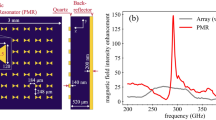

Inspired by the above simulation results, we proceed to fabricate VSRR structureswith two different sizes as shown in Fig. 2 (right). Thegeometries for the two different structures are identical to the SRR dimensions usedin simulation except the base length L. One sample has shorter base length of170 nm while the other 220 nm. The reason for us to studythese VSRRs of two different sizes is to establish the baseline for our next step ininvestigating the plasmon coupling between two closely spaced VSRRs of the same twosizes. The periodical lattice spacing in both samples has been chosen to be500 nm to avoid coupling with its neighbors so that these VSRRs can betreated as being isolated. We have performed transmittance measurement on the twosamples and the results are shown in Fig. 2 (left). There is apronounced resonance dip for each isolated VSRR around 1200-nm wavelength which isthe so-called LC resonance also referred to as the magnetic plasmon resonancebecause of the participation of magnetic dipole in the plasmon oscillation41. The resonance difference between the two isolated VSRRs ofdifferent dimensions is Δω ≈20 THz in the absence of plasmon coupling between them. The deepertransmittane dip observed from the lager VSRRs is the result of their greater areacoverage density over the substrate relative to their smaller counterparts.

Electromagnetic response of isolated VSRR.

Experimental transmittance spectra for isolated VSRR with 500 nmperiod in x and y directions on a glass (BK7) substrate. The purple andorange spectral lines correspond to the isolated VSRR with L =170 nm and 220 nm, respectively. The resonancedifference is about 20 THz in frequency indicated by the magentadashed lines. The images on right represent the top view SEM pictures of thecorresponding structures. Scale bars: 250 nm.

We next investigate the resonance tuning of coupled VSRRs by fabricating a series ofdimer samples with different spacing as shown schematically in Fig.3a with the expectation to reveal the strong magnetic dipole coupling invertical dimers because VSRRs can be placed much closer to each other. The twocoupled VSRRs have the same geometries except different base lengths ofL1 = 170 nm and L2 =220 nm (the resonance position of each when isolated is shown in Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 3a they areplaced in parallel along x-axis with their centers aligned on y-axis. Figure 3b shows the SEM images (oblique views) of the gold VSRR dimersample with 50-nm gap separation fabricated on a glass (BK7) substrate. The inset inFig. 3b is an enlarged perspective view of four VSRRdimers with their two prongs sitting precisely on the two ends of the base rod.

Geometry of VSRR dimer.

(a) Schematic diagrams of VSRR dimer unit cell with designed parameters:L1 = 170 nm, L2 =220 nm, H1 = 20 nm,H2 = 60 nm, W = 60 nm andP = 500 nm. A parameter G is introduced for thegap separation between VSRRs. (b) The 45° SEM micrograph with thezoom-in view (inset) for the sample with G = 50 nm. Scalebar: 500 nm.

Four VSRR dimer samples with gap separations G of 40, 50, 70 and90 nm are fabricated and measured. All samples have the same latticeconstant of P = 500 nm in both x and y directions between eachdimer unit cell (metamolecules) to avoid coupling between VSRRs from neighboringunit cell. Figure 4a represents the transmittance spectrasimulated at four different gap separations between the two VSRRs where twotransmittance dips emerge. The measurement (Fig. 4b) of theseVSRR arrays reveals similar resonance features in reasonably good agreement with thesimulation. The difference between the measurement and simulation is due to the VSRRsize variation and roughness of fabricated samples that deviate from the exactdimensions and boundary condition of perfectly smooth structures used in thesimulation. The two transmittance dips are clearly associated with the magneticplasmon modes that originate from the two VSRRs of different dimensions. As theseparation between the two VSRRs reduces, the coupling between them becomesstronger, shifting the two resonances further apart as revealed from the simulationand measurement in Figs. 4a and 4b,respectively.

Electromagnetic spectra of VSRR dimers.

(a) Simulation and (b) experimental transmittance spectra for VSRR dimerswith various gaps. The colored shade highlights the position for eachresonance mode. (c) Surface current density (in arbitrary unit andlogarithmic scale) of the VSRR dimer with G = 50 nm undernormal illumination at respective resonance wavelengthωa+b andωa−b as indicated in (a).Arrows present the direction of induced surface current. Right: directionsof induced electric and magnetic dipoles.

Discussion

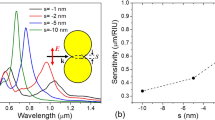

Plasmon hybridization theory42 has been proposed to reveal theorigin of plasmon resonances of complex metal nanostructures as interactions betweenconstituent elements much like the coupling between two closely spaced quantumstructures where electron wavefunctions overlap. This theory has been provensuccessful in predicting and analyzing optical responses of assemblies of metalnanoparticles of various shapes including dimers among others43,44. The plasmon hybridization that has been reported so far primarilyoriginates from interactions of electric and magnetic dipoles and higher-ordermulti-pole oscillations of individual nanoparticles that make up a complexnanostructure10,45. The VSRR dimer structures reportedhere offer a perfect venue to explore enhanced magnetic interaction betweenindividual nanostructures that also influences the optical response of a compositemetal structure. Indeed the VSRRs have much stronger magnetic coupling than thoseplanar ones placed next to each other and their coupling strength can be controlledby their spatial separation G. In the hybridization picture, each VSRRsupports a dipole oscillation with its own plasmon resonance frequency atωa or ωb dependingon the VSRR dimensions, when two VSRRs are brought closer in the configuration shownin Fig. 3a their electric dipoles transversely couple to eachother while the magnetic ones interact longitudinally, both contributing to thehybridization of resonance modes in the metamolecules that shifts the positions oforiginal magnetic resonances ωa andωb supported by the isolated VSRRs. It can beseen from the simulation result of the induced surface current distribution of theVSRR dimers that are separated by G = 50 nm under normalillumination in Fig. 4c that two resonance modes emerge fromthe coupled VSRRs, one associated with parallel induced electric currents in the twoconstituent VSRRs that enhances both electric and magnetic dipole moments and theother with reduced moments from anti-parallel currents. The dominance of theelectric coupling dictates that the “bonding” mode hasout-of-phase electric dipoles, resulting in out-of-phase magnetic dipole momentoscillation as well (marked as ωa−b fortheir out-of-phase characteristic), while the “anti-bonding”mode (marked as ωa+b) has in-phase electric andmagnetic dipoles. Since the two VSRRs have different dimensions, we haveωa ≠ωb and if we assume ωa< ωb the result of hybridization is to yield“bonding” and “anti-bonding” modes withtheir mode resonances separated further apart according toωa−b <ωa < ωb< ωa+b. It is interesting to point out thatthe resonance at the longer wavelength (markedωa−b) appears to be weaker as the gapseparation becomes smaller, because this “bonding” modeoriginated from the two opposing electric and magnetic dipoles in the dimer as shownin Fig. 4c interacts weakly with the incident field. As aconsequence, the resonance feature in the transmittance spectra at the shorterwavelength is always stronger than the one at the longer wavelength as shown inFigs. 4a and 4b. This plasmonhybridization of two unequal VSRRs shifts the plasmon resonances much like thecoupling between two interacting semiconductor quantum dots (QDs) of differentsizes. While each QD supports a confined state with a different energy, the resultof coupling because of their electron wavefunction overlap is that the two confinedstates are pushed further apart. The amount of energy shifting reflects the couplingstrength which depends on the geometries of the two QDs and is particularlysensitive to their spatial separation. We have also observed the similar behavior inthe coupled VSRRs by systematically varying the separation G within a SRRdimer. Figure 5 shows the simulation and measurement ofresonance frequency separation Δω =ωa+b −ωa−b of the“anti-bonding” and “bonding” for thefour samples with VSRR spacing from 40 to 90 nm under normalillumination. The coupled resonance separation Δω isconsistently greater than the resonance frequency difference (~20 THz)obtained from the transmittance measurement of the isolated VSRRs of same twodifferent sizes shown in Fig. 2. As the spacing Gbetween the VSRRs reduces, Δω increases rapidly withthe decreasing G.

Bonding and anti-bonding splitting vs. the gap in VSRR dimer.

Orange line and magenta dots correspond to simulation and measurementresults, respectively. Blue line: a second-order polynomial fitting forexperimental results. Insets represent the corresponding SEM image with gapsizes G = 40, 50, 70 and 90 nm between SRRs (left toright).

To summarize, we have fabricated a series of metamolecules consisting of eitherisolated VSRRs or their coupled dimers with different SRR spacing using e-beamlithography with high precision alignment technique. These VSRR metamolecules havethe advantage of direct coupling to both the electric and magnetic components of thenormal incident wave in comparison to their planar counterpart that only interactswith the electric field, resulting in stronger magnetic response. By conductingsimulation and measurement of the optical transmittance, we have observedhybridization of magnetic plasmon modes associated with constituent VSRRs inmetamolecules where bonding and anti-bonding modes emerged. We have found that theenergy separation between the bonding and anti-bonding modes in metamoleculesdepends strongly on the gap separation in VSRR dimers. The tuning capability enabledby the magnetic plasmon mode coupling can be explored for developing frequencyselective functional devices.

Methods

Fabrication of VSRRs

VSRR structures with different feature sizes are fabricated using electron beamlithography with high precision alignment technology. A 200 nm-thick495 K PMMA (polymethyl methacrylate) layer was spin-coated at4000 rpm on cover glass and then baked for 3 min at180°C. The conductive polymer Espacer is then spin-coated at1500 rpm over the PMMA layer to avoid the charging problem during thee-beam exposure process. An ELS-7000 electron beam lithography system (ElionixInc., Tokyo, Japan) is used for exposure with 100 keV accelerationvoltage and 30-pA current. The position of the VSRR base rod was defined on thePMMA resist relative to the two 100-nm-thick gold cross alignment marks whichwere first fabricated on the substrate for precise alignment during e-beamexposure process. After exposure, the sample was rinsed with de-ionized water toremove Espacer, then developed in solution of methyl isobutyl ketone (MIBK) andisopropyl alcohol (IPA) of MIBK:IPA = 1:3 for 60 seconds, rinsed again, thistime with IPA, for 20 seconds and blow-dried with nitrogen gas. Once thedevelopment of the resist was completed, a gold film with designed thickness wasthermally deposited on the sample and the un-patterned regions were removedusing a lift-off process. Subsequently, the two VSRR prongs were fabricated in asimilar fashion by the second e-beam exposure and lift-off process. The area ofeach fabricated structure is 75 ×75 μm2 on a cover glass substrate.

Optical measurement and simulation

The spectra were measured by a self-assembled micro-spectrometer and an invertedOlympus microscope IX-70 (10× IR objective with numerical aperture NA= 0.3, long working distance condenser with NA = 0.3, visible to near-infraredpolarizer U68-750 from Edmoud Optics and 100 W halogen light source)equipped with two spectrometer (BTC111E for λ = 400 nm toλ = 1000 nm with ~0.5 nm resolution and BTC261Efor λ = 900 nm to λ = 1700 nm with~5 nm resolution) from B&W Tek, Inc. All transmittancespectra were normalized by an un-patterned region of the cover glasssubstrate.

FEM Simulation

All simulation results were performed with the commercial software COMSOLMultiphysics by solving 3D Maxwell equations. Both isolated and coupled VSRRdimers are simulated with periodic boundary conditions under x-polarized lightillumination. The refractive index of cover glass substrate is fixed at 1.51.The permittivity of gold in the near infrared regime is described by theDrude-Lorentz model with plasmon frequency ωp =8.997 eV and damping constant Γp =0.14 eV, which is two times larger than that of the bulk valuebecause of the surface scattering and grain effects.

References

Zheludev, N. I. & Kivshar, Y. S. From metamaterials to metadevices. Nat. Mater. 11, 917–924 (2012).

Lal, S., Link, S. & Halas, N. J. Nano-optics from sensing to waveguiding. Nat. Photon. 1, 641–648 (2007).

Sun, G., Khurgin, J. B. & Yang, C. C. Impact of high-order surface plasmon modes of metal nanoparticles on enhancement of optical emission. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 171103 (2009).

Chen, W. T. et al. High-efficiency broadband meta-hologram with polarization-controlled dual images. Nano Lett. 14, 225–230 (2013).

Pors, A., Albrektsen, O., Radko, I. P. & Bozhevolnyi, S. I. Gap plasmon-based metasurfaces for total control of reflected light. Sci. Rep. 3, 2155 (2013).

Barnes, W. L., Dereux, A. & Ebbesen, T. W. Surface plasmon subwavelength optics. Nature 424, 824–830 (2003).

Khurgin, J. B. & Sun, G. Scaling of losses with size and wavelength in nanoplasmonics and metamaterials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 211106 (2011).

Lu, X., Shi, J., Liu, R. & Guan, C. Highly-dispersive electromagnetic induced transparency in planar symmetric metamaterials. Opt. Express 20, 17581–17590 (2012).

Huang, Y.-W. et al. Toroidal Lasing Spaser. Sci. Rep. 3, 1237 (2013).

Shafiei, F. et al. A subwavelength plasmonic metamolecule exhibiting magnetic-based optical Fano resonance. Nat. Nano. 8, 95–99 (2013).

Luk'yanchuk, B. et al. The Fano resonance in plasmonic nanostructures and metamaterials. Nat. Mater. 9, 707–715 (2010).

Kaelberer, T., Fedotov, V. A., Papasimakis, N., Tsai, D. P. & Zheludev, N. I. Toroidal dipolar response in a metamaterial. Science 330, 1510–1512 (2010).

Huang, Y.-W. et al. Design of plasmonic toroidal metamaterials at optical frequencies. Opt. Express 20, 1760–1768 (2012).

Savasta, S. et al. Nanopolaritons: Vacuum Rabi splitting with a single quantum dot in the center of a dimer nanoantenna. ACS Nano 4, 6369–6376 (2010).

Schlather, A. E., Large, N., Urban, A. S., Nordlander, P. & Halas, N. J. Near-field mediated plexcitonic coupling and giant Rabi splitting in individual metallic dimers. Nano Lett. 13, 3281–3286 (2013).

Anker, J. N. et al. Biosensing with plasmonic nanosensors. Nat. Mater. 7, 442–453 (2008).

Liu, N. et al. Magnetic plasmon formation and propagation in artificial aromatic molecules. Nano Lett. 12, 364–369 (2011).

Ekmekci, E. et al. Frequency tunable terahertz metamaterials using broadside coupled split-ring resonators. Phys. Rev. B 83, 193103 (2011).

Powell, D. A., Lapine, M., Gorkunov, M. V., Shadrivov, I. V. & Kivshar, Y. S. Metamaterial tuning by manipulation of near-field interaction. Phys. Rev. B 82, 155128 (2010).

Enkrich, C. et al. Magnetic metamaterials at telecommunication and visible frequencies. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 203901 (2005).

Dolling, G., Wegener, M., Schadle, A., Burger, S. & Linden, S. Observation of magnetization waves in negative-index photonic metamaterials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 231118–231113 (2006).

Keiser, G. R. et al. Decoupling crossover in asymmetric broadside coupled split-ring resonators at terahertz frequencies. Phys. Rev. B 88, 024101 (2013).

Soukoulis, C. M. & Wegener, M. Past achievements and future challenges in the development of three-dimensional photonic metamaterials. Nat. Photon 5, 523–530 (2011).

Moser, H. O. & Rockstuhl, C. 3D THz metamaterials from micro/nanomanufacturing. Laser & Photon. Rev. 6, 219–244 (2012).

Kanté, B. et al. Symmetry breaking and optical negative index of closed nanorings. Nat. Commun. 3, 1180 (2012).

Sersic, I., Frimmer, M., Verhagen, E. & Koenderink, A. F. Electric and magnetic dipole coupling in near-infrared split-ring metamaterial arrays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103 (2009).

Feth, N. et al. Electromagnetic interaction of split-ring resonators: The role of separation and relative orientation. Opt. Express 18, 6545–6554 (2010).

Zeng, Y., Dineen, C. & Moloney, J. V. Magnetic dipole moments in single and coupled split-ring resonators. Phys. Rev. B 81, 075116 (2010).

Valentine, J. et al. Three-dimensional optical metamaterial with a negative refractive index. Nature 455, 376–379 (2008).

Liu, N., Liu, H., Zhu, S. N. & Giessen, H. Stereometamaterials. Nat. Photon. 3, 157–162 (2009).

Liu, N. et al. Three-dimensional photonic metamaterials at optical frequencies. Nat. Mater. 7, 31–37 (2008).

Tseng, M. L. et al. Fabrication of multilayer metamaterials by femtosecond laser-induced forward-transfer technique. Laser & Photon. Rev. 6, 702–707 (2012).

Yen, T. J. et al. Terahertz magnetic response from artificial materials. Science 303, 1494–1496 (2004).

Gundogdu, T. F. et al. Experimental demonstration of negative magnetic permeability in the far-infrared frequency regime. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 084103 (2006).

Fan, K., Strikwerda, A. C., Zhang, X. & Averitt, R. D. Three-dimensional broadband tunable terahertz metamaterials. Phys. Rev. B 87, 161104 (2013).

Wu, P. C. et al. Magnetic plasmon induced transparency in three-dimensional metamolecules. Nanophotonics 1, 131–138 (2012).

Wu, P. C. et al. Vertical split-ring resonator based nanoplasmonic sensor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 033105 (2014).

Chen, W. T. et al. Optical magnetic response in three-dimensional metamaterial of upright plasmonic meta-molecules. Opt. Express 19, 12837–12842 (2011).

Kriegler, C. E., Rill, M. S., Linden, S. & Wegener, M. Bianisotropic photonic metamaterials. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Quantum Electron 16, 367–375 (2010).

Marqués, R., Medina, F. & Rafii-El-Idrissi, R. Role of bianisotropy in negative permeability and left-handed metamaterials. Phys. Rev. B 65, 144440 (2002).

Linden, S. et al. Magnetic response of metamaterials at 100 terahertz. Science 306, 1351–1353 (2004).

Prodan, E., Radloff, C., Halas, N. J. & Nordlander, P. A hybridization model for the plasmon response of complex nanostructures. Science 302, 419–422 (2003).

Nordlander, P., Oubre, C., Prodan, E., Li, K. & Stockman, M. I. Plasmon hybridization in nanoparticle dimers. Nano Lett. 4, 899–903 (2004).

Zhang, J. et al. Tailoring alphabetical metamaterials in optical frequency: Plasmonic coupling, dispersion and sensing. ACS Nano 8, 3796–3806 (2014).

Jain, P. K., Eustis, S. & El-Sayed, M. A. Plasmon coupling in nanorod assemblies: Optical absorption, discrete dipole approximation simulation and exciton-coupling model. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 18243–18253 (2006).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support from Ministry of Science and Technology,Taiwan (Grant Nos. 103-2745-M-002-004-ASP, 102-2911-I-002-505 and103-2911-I-002-594) and Academia Sinica (Grant No. AS-103-TP-A06). They are alsograteful to National Center for Theoretical Sciences, Taipei Office, MolecularImaging Center of National Taiwan University, National Center for High-PerformanceComputing, Taiwan and Research Center for Applied Sciences, Academia Sinica, Taiwanfor their support. G. Sun acknowledges support from AFOSR (Grant No.FA9550-14-1-0196, Dr. Gernot Pomrenke, Program Manager) and from AOARD (Grant No.AOARD-14-4073, Dr. Kenneth Caster, Program Manager). N. I. Zheludev alsoacknowledges sponsorship of: Science and Engineering research Council, UK andMinistry of Education of Singapore (Grant No. MOE2011-T3-1-005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.C.W. and W.L.H. designed and performed the experiments and data analysis and wrotethe manuscript; W.T.C., Y.-W.H. and C.Y.L. performed the experiments and dataanalysis; A.Q.L. and N.I.Z. discussed the experiments and prepared manuscripts; G.S.developed the theoretical aspects and wrote the manuscript; D.P.T. designedexperiments, analyzed the results and prepare the manuscripts. All authorsdiscussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0International License. The images or other third party material in this article areincluded in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicatedotherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the CreativeCommons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder inorder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, P., Hsu, WL., Chen, W. et al. Plasmon coupling in vertical split-ring resonator metamolecules. Sci Rep 5, 9726 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09726

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09726

This article is cited by

-

Multilayer metal-insulator-metal plasmonic vertical Mach-Zehnder sensor based on semi-circular slit-aperture nanostructures

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2024)

-

Three-dimensional nanoprinting via charged aerosol jets

Nature (2021)

-

The FDTD simulation of microring feedback bend-based coupling resonator system for electromagnetically-induced transparency-like effect

Pramana (2019)

-

Hybrid plasmonic label-free multi-analyte refractive index sensor

Optoelectronics Letters (2019)

-

Dynamic-Shift Single- and Double-Negative Refractive Index in a Novel Three-Dimensional Metamaterial

Plasmonics (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.