Abstract

One of the key characteristics of cancer cells is an increased phenotypic plasticity,driven by underlying genetic and epigenetic perturbations. However, at asystems-level it is unclear how these perturbations give rise to the observedincreased plasticity. Elucidating such systems-level principles is key for animproved understanding of cancer. Recently, it has been shown that signalingentropy, an overall measure of signaling pathway promiscuity and computable fromintegrating a sample's gene expression profile with a protein interactionnetwork, correlates with phenotypic plasticity and is increased in cancer comparedto normal tissue. Here we develop a computational framework for studying the effectsof network perturbations on signaling entropy. We demonstrate that the increasedsignaling entropy of cancer is driven by two factors: (i) the scale-free (or nearscale-free) topology of the interaction network and (ii) a subtle positivecorrelation between differential gene expression and node connectivity. Indeed, weshow that if protein interaction networks were random graphs, described by Poissondegree distributions, that cancer would generally not exhibit an increased signalingentropy. In summary, this work exposes a deep connection between cancer, signalingentropy and interaction network topology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the key features of cancer is an increased cellular plasticity, mediated by anincreased promiscuity in signaling patterns and driven by underlying genetic andepigenetic aberrations which cause a fundamental rewiring of the intracellular signalingnetwork1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Every aberration found in a cancercell can be thought of as a perturbation if the aberration affects the genefunctionally. Such perturbations can be classed as activating, if they result in anincreased functional activity of the gene (e.g. amplification and overexpression ofERBB2 in breast cancer), or inactivating, if it compromises gene function(e.g. silencing through promoter DNA methylation). Whilst the effect of certain specificperturbations on gene function can be predicted, it is much less clear how individualperturbations affect the cellular phenotype as a whole, since this depends on thecollective nature of the other aberrations that are present in the same cell. Predictingthe net effect of multiple perturbations in a signaling network is hard due to complexeffects such as pathway redundancy and epistasis3,6. Moreover, in thecontext of cancer, although the effect of specific aberrations on cell function isknown, it is yet unclear how individual cancer perturbations may contribute to theobserved increased signaling promiscuity and phenotypic plasticity.

One way to approach this challenge computationally, is to anchor the analysis on globalmeasures which capture salient features of the cellular phenotype and which arecomputable from, say, a sample's molecular profile (e.g. asample's gene expression profile). Here we are particularly interested inmeasuring signaling promiscuity since evidence is mounting that this underlies asample's phenotypic plasticity8. In previous work we havestarted to explore a measure which approximates intra-sample signaling promiscuity, andwhich is known as network signaling entropy9,10,11. Signalling entropyis computed from integrating a sample's genome-wide gene expression profilewith a protein interaction network and, as shown by us, provides a surprisingly goodestimate of a sample's height in Waddingtons's differentiationlandscape, with human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) exhibiting the highest levels ofentropy10. Indeed, signalling entropy was able to discriminatecellular samples according to their differentiation potential within distinct lineages,including hematopoietic, mesenchymal and neural lineages and with terminallydifferentiated cells within these lineages exhibiting the lowest levels of entropy10. Importantly, signaling entropy was also found to be higher in cancercompared to normal tissue, consistent with the view that cancer cells represent a moreundifferentiated stem-cell like state, characterised by an increase in phenotypicplasticity8,10.

Given that increased signaling entropy is such a robust and characteristic feature ofdifferentiation potency and cancer and that it is also amenable to computation9,10, it is of great theoretical and biological interest to study thechanges in entropy caused by cellular network perturbations. In the context of cancer,two well-known network perturbations are the overexpression and underexpression ofoncogenes and tumour suppressor genes, respectively and although these perturbationsare known to result in the uncontrolled activation of cell-growth and cell-proliferationpathways, it remains unclear how these perturbations affect signalling promiscuity. Inorder to deepen our understanding, we here decided to study the effect of suchperturbations on signaling entropy, using both simulated and real data and using avariety of different network types in order to assess the impact of network topology.Specifically, we consider Erdos-Renyi random (Poisson) graphs12, scalefree networks13, as well as real protein-protein interaction (PPI)networks14,15,16. In doing so, we discover that in Poissonnetworks, perturbations (be they activating or inactivating) lead to reductions in theglobal entropy, but that this is not true for scale-free and more realistic PPInetworks. In networks exhibiting a scale-free, or near scale-free topology, we show thatgene expression perturbations affecting hubs exhibit a striking bi-modality, leading toincreases or decreases in the global entropy rate depending on the directionality of theexpression change. We further expose a subtle yet significantly positive correlationbetween differential gene expression in cancer and node-degree, which we show drives theincreased signaling promiscuity of cancer, but only if the underlying proteininteraction network has a scale-free (or near scale-free) topology. Thus, this workmakes a deep connection between a defining feature of the cancer phenotype, i.e. highsignaling entropy, its differential gene expression pattern and the (near) scale-freetopology of real PPI networks.

Although there are many studies on network perturbations, it is worth clarifying that thenetwork perturbations and outcome of interest (i.e. the entropy rate) considered in thiswork are very different from the perturbations and outcomes of interest considered inprevious studies17,18,19,20,21. Specifically, we consider networkperturbations which only alter the local edge weights without altering the underlyingnetwork topology9,10,22. Moreover, our network perturbations can beboth activating as well as inactivating, representing the two different types of canceralterations affecting oncogenes and tumour suppressors, respectively. In contrast, muchof the previous literature has dealt with the effects of removing specific nodes inunweighted networks17,18, a type of inactivating perturbation whichalters the underlying network topology, focusing on tolerance and robustness as outcomemeasures17,18,19,21. Thus, from a network theoretical perspective,the important novel insights reported in this work are made possible by considering anovel type of network perturbation in the context of weighted networks defined by astochastic matrix. We should also stress that our outcome of interest, signalingentropy, is a systems-level measure that is constructed from the genome-wide expressionprofile of a given sample and therefore has little to do with the protein signalingdisorder measures considered by other studies and which do not use gene expressiondata23.

Results

Increased signaling entropy in cancer is driven by overexpression of hubgenes

In earlier work we demonstrated that signaling entropy, a measure of thesignaling promiscuity in a cellular sample, is increased in cancer compared tonormal tissue, irrespective of tissue type9,10,11. Thisincreased signaling entropy is consistent with the observed increased phenotypicplasticity of cancer cells (see e.g. Ref. 8). Thus,increased signaling entropy has emerged as a cancer systems hallmark9,11. Signaling entropy is estimated as the entropy rate24 of a sample-specific stochastic matrix which models thesignaling interactions in the sample (Methods). This stochastic matrix iscomputed by integrating the gene expression profile of the sample with acomprehensive PPI network, invoking the mass-action principle to define theedge-weights in the network (Methods). The mass-action principle is basedon the assumption that two proteins, which have been reported to interact, aremore likely to interact in a given sample if both are highly expressed in thatsample.

Here we wanted to shed light on why, theoretically, we observe increasedsignaling entropy in cancer. We decided to use liver cancer as a model sinceliver represents a relatively homogeneous tissue and is thus less affected bycontaminating non-epithelial cells. We downloaded gene-normalised RNA-Seq datafor a matched subset of 50 normal liver and 50 liver cancer samples from TheCancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). Confirming our earlier work using Affymetrix geneexpression data9,10,11, liver cancer exhibited a significantlyhigher signaling entropy rate compared to normal liver tissue (Fig. 1A). Randomisation of the RNA-Seq profiles over the nodes inthe network resulted in a significantly reduced difference in entropy ratebetween normal and cancer tissue (Fig. 1A), indicating (aspointed out by us previously11) that the entropy increase incancer is driven by a subtle interplay between specific gene expression changesand where these happen on the network. Specifically, we posited that thetopological properties of the genes undergoing the largest changes in geneexpression would be key features dictating the change in signalling entropy.

Increased entropy in liver cancer is driven by increased entropy athubs:

(A) Boxplots comparing the entropy rate (SR) of 50 normal liver samples (N)to 50 matched liver cancer specimens (C), derived from RNA-Seq data of theTCGA consortium. P-value is from a one-tailed Wilcoxon rank sum test,testing the hypothesis that entropy rate is higher in cancer. Also shown isthe SR between normal and liver cancer for a case where the gene expressionprofiles were randomly permuted (perm) over the interaction network. Observehow the difference in the SR between normal and cancer is reduced and eventakes an opposite directionality, demonstrating that the interplay betweengene expression changes and network topology is dictating the highersignaling entropy in cancer. (B) Boxplots showing the change in the meanlocal entropy rate (LSR)(〈πiLSi〉C−〈πiLSi〉N)between normal and cancer of each node (gene) as a function of node degree,positive values indicating higher values in cancer. (C) Scatterplot of thedifferential change in the mean local entropy rate against the differentialchange in the mean invariant measure (INVP)(〈πi〉C−〈πi〉N).Each data point is one node (gene). (D) Boxplots showing the change in themean local entropy (LS) of each node (gene)(〈LSi〉C−〈LSi〉N)between normal and cancer, as a function of node degree.

Since each gene i contributes an amountπiLSi to the entropy rate of agiven sample (Methods), we computed for each gene the difference in the means ofits local entropy rate, πiLSi, betweennormal and cancer tissue. In order to help interpretation, we also computed foreach gene the difference in the means of the invariant measureπi between normal and cancer, as well asthe difference in the average local entropy LSi (Methods). Allthese changes were assessed in relation to the connectivity of the genes in thenetwork. We observed that the entropy rate increase in cancer is driven mainlyby hubs, i.e. the nodes of highest degree in the network (Fig.1B). Changes to the local entropy rates were driven by concomitantchanges in the average invariant measure (Fig. 1C). Thus,hubs exhibited preferential increases in their average invariant measure, whilstalso demonstrating positive increases in the average local entropy (Fig. 1D). Since the invariant measure value at a nodei represents the steady-state probability of finding a random walkerat this node, the observed preferential increase in the invariant measure athubs means that there is an increased signaling flux through these hub nodes incancer.

To gain insight as to why there is an increased signaling flux through hubs incancer, we focused on the hub gene exhibiting the largest increase in the localentropy rate. This was the gene BUB1 (Fig. 2A). Ascatterplot of the expression values of BUB1 and that of its neighbors(813 neighbors) in a representative normal sample versus the correspondingexpression values in a representative cancer sample, demonstrates that most ofthe expression differences involve increases in gene expression, implicatingboth the hub itself as well as some of its neighbors (Fig.2B). Thus, for the majority of neighbors of BUB1, theincreased expression of BUB1 will, according to the mass actionprinciple, drive increased signaling through this hub. Indeed, for each one ofBUB1's neighbors we ranked its neighbors according to thelargest increase in gene expression, revealing that the original hub (i.e.BUB1) ranked among the top 2% centile for 99% of the hub neighbors(SI Appendix, fig. S1). Interestingly, this effect wasnot unique to BUB1 since high-degree hubs generally exhibited asignificant skew towards increased gene expression in cancer (Fig. 2C–D).

Preferential overexpression of hub genes in cancer:

(A) Boxplot showing the local entropy rate (LSR) against normal/cancerstatus, for the hub gene (BUB1) exhibiting the largest increase inthe local entropy rate. P-value is from a Wilcoxon rank sum test. (B)Scatterplot of gene expression values between a representative normal(x-axis) and cancer (y-axis) sample for the gene showing the largestincrease in the local entropy rate (gene BUB1, marked in red) andthat of its neighbours in the PPI network (over 800 neighbours, shown inblack). (C) Boxplot of the average difference in gene expression betweennormal and cancer (positive values indicate higher expression in cancer)against node-degree class. Observe how the highest-degree hubs showpreferential increased expression in cancer, whereas the largest reductionsin expression target low-degree nodes. (D) Density plot of the averagedifference in gene expression between normal and cancer for two classes ofgenes: hubs (defined as nodes of degree >316) and nodes of degree1 (k = 1). The number of each is indicated and the P-value is from aKolmogorov-Smirnov test, testing for a difference in their statisticaldistributions.

Confirming the biological significance of these results, we reached very similarconclusions by repeating the above analysis in the independent Affymetrix geneexpression data set of normal liver and liver cancer tissue25 (SIAppendix, fig. S2–S3). Thus, the increased entropy rate in livercancer is driven mainly by the increased expression of the highest degree hubsin the PPI network.

Effect of cancer perturbations on signaling entropy

That the highest degree genes show preferential expression increases in cancer(Fig. 2C–D, SI Appendix, fig. S3) suggestsan intricate link between network topology and differential expression.Confirming this further, in both liver expression sets we also observed that thegenes exhibiting the largest, or most significant, decreases in expressionpreferentially mapped to low-degree nodes (Fig.2C–D, SI Appendix fig. S3–S4).

This intricate correlation between differential expression and node degreemotivated us to pursue a deeper understanding of the complex interplay betweennetwork topology, gene expression perturbations and entropy rate. Intuitively,and from the perspective of a gene i that interacts with an oncogenichub, overexpression of the latter would lead to an increased outgoing signalingflux of node i towards the hub, potentially leading to an increase in theoverall entropy rate (Fig. 3A). Interestingly,underexpression of a low-degree node, which may connect to a hub either directlyor indirectly through an intermediate node i would also lead to anincreased signaling flux through the hub (Fig. 3A). Thus,the two characteristic topological features of differential gene expressionchanges in cancer could synergize causing increased signaling flux through keyhubs. To test whether this is indeed the case, we performed a perturbationanalysis for the top 100 genes ranked according to fold-change between normalliver and liver cancer. The initial signaling distribution was defined byinvoking the mass action principle on the average expression profile over all 50normal liver samples. Next, each of the top 100 ranked genes was individuallyperturbed by changing its expression level according to the observed differencebetween normal and cancer tissue. Confirming our hypothesis, underexpressedgenes (which generally did not target hubs) led to marginal increases in theentropy rate, whilst overexpressed hubs caused significant entropy increases(Fig. 3B). Interestingly however, overexpression ledto marginal entropy decreases whenever it did not target the highest degreehubs, suggesting that such perturbations draw away signaling flux from the majorhubs (Fig. 3B).

Effect of cancer perturbations on signaling entropy:

(A) Examples of two expression perturbations typically found in cancer. Topdepicts the example of an oncogenic hub undergoing overexpression in cancer,which has the effect of drawing in signaling flux from a neighbour i.Example at the bottom depicts the underexpression of a low-degree“tumour suppressor” node (e.g. a transcripton factor),which from the perspective of node i causes, indirectly, an increasedsignaling flux through the nearby hub. (B) Perturbation analysis of the top100 genes ranked according to fold-change between normal and liver cancer.Plots shows the entropy rate after perturbation (y-axis) against node-degree(x-axis), with colors indicating over or underexpression. Black horizontalline defines the entropy rate of the average expression profile of normalliver (i.e. before the perturbation).

The effect of perturbations on signaling entropy is dependent on networktopology

To further investigate the effect of individual perturbations on signalingentropy, as well as the role of the underlying network topology, we devised asimulation framework on toy networks, perturbing each node in turn, andrecording the effect on the entropy rate (Fig. 4A,Methods). To simplify the analysis we considered an initial uniform edge weightconfiguration, defining an unbiased random walk on the graph. We note that thisinitial configuration represents a state of relatively high signaling entropy,but not of maximal entropy (see Methods). As activating perturbationswe consider local increases in gene expression, whereby all the weights of edgesconverging on a perturbed node i are assigned a relatively large weight(Fig. 4B). Thus, as seen from the perspective of aneighboring node j, before perturbation, node j has maximal localentropy, given by log kj (where kj is thedegree of node j), whilst after the perturbation, the node'slocal entropy is close to 0 (Fig. 4B). We emphasize againthat although in the initial configuration all local entropies are maximal, thatthe initial entropy rate over the whole network is not maximal (see Methods).Thus, after the perturbation, the global entropy rate of the network couldincrease or decrease.

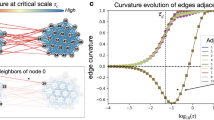

Cancer perturbations may increase the entropy rate on networks withscale-free topology but not on random Poisson graphs:

(A) A cartoon of the network perturbation analysis: each node i of thenetwork is perturbed in turn by changing its expression value. The case ofoverexpression is here indicated in red. The increased expression draws insignaling flux from neighbours (only one perturbed edge is shown). Theentropy rate of the network after perturbing node i,SRi, is computed and compared to the entropy rateSR of the original unperturbed network. For n nodes in thenetwork we get a distribution of entropy rate changes (SRi− SR, i = 1,…,n). (B) Zoomed-inversion of a network perturbation, whereby a node i undergoes aperturbation (here overexpression). From the perspective of a neighbouringnode j, the perturbation causes a low signaling entropy configurationaround node j. Key question is how does this perturbation affect theglobal entropy rate. (C) Perturbation analysis result, in which each node(gene) of the network was perturbed through overexpression (red) orunderexpression (green). Plotted is the global entropy rate (SR) after theperturbation (y-axis) against the degree of the perturbed node (x-axis), for3 different networks: Erdos-Renyi (ER) graph, scale-free (SF) network andthe full PPI network (PPI). Black dashed line denotes the entropy ratebefore the perturbation. In each plot there as many data points as there arenodes in the network, each value corresponding to the perturbation of onlyone node. Number of nodes (nn), average degree (avK) and median degree(medK) are given.

In order to understand the potential impact of network topology, we firstconducted the perturbation analysis above on Erdos-Renyi (ER) random graphs, forwhich the degree distribution is Poisson. For such ER graphs, we observed thatactivating perturbations (i.e. increases in gene expression), always led to areduction in the global entropy rate, irrespective of node degree (Fig. 4C). Repeating the analysis for inactivatingperturbations, i.e causing nodes to undergo underexpression, we observed thatalmost all nodes led to a decrease in entropy. Thus, given that cancer ischaracterised by an increase in signaling entropy, this suggests that theemergence of an increased signaling promiscuity regime in cancer must be dueeither to specific topological features not present in random graphs, or tonon-random combinations of perturbations.

To investigate this further, we next performed the same perturbation analysisabove, but now on networks characterised by a scale-free (or near scale-free)topology, a key feature of real biological networks26. Thescale-free networks were matched to the same size and average connectivity thanthe previously considered Erdos-Renyi graphs. Remarkably, in scale-free networkswe observed that activating perturbations exhibited a bi-modal response, withperturbations at lower-degree nodes resulting in a reduction of the globalentropy rate, whilst hubs exhibited increases (Fig. 4C).In fact, we observed two distinct regimes with an opposite functionalrelationship between entropy change and node-degree (Fig.4C). In the low-degree regime, the entropy rate decreased as nodedegree increases, whereas in the high-degree regime one observes entropyincreases (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, this bi-phasicbehaviour was not seen for inactivating perturbations where we observed amonotonic decrease of entropy with node degree (Fig. 4C).In stark contrast to Poisson networks, high-degree nodes in the scale-freenetwork exhibited a bi-modal response dependent on the directionality of theperturbation (Fig. 4C): overexpressed hubs led to entropyincreases, while underexpressed hubs led to corresponding decreases.

Next, we wanted to test whether this bi-phasic and bi-modal behaviour is alsoseen in real PPI networks. We first checked that our PPI network exhibited anapproximate scale-free topology (SI Appendix, fig. S5). Its clusteringcoefficient was also significantly higher than that of a degree-distributionmatched scale-free network (SI Appendix, fig. S5). Performing the perturbationanalysis on the PPI network, we observed once again two phases, which wasparticularly striking for activating perturbations, with one phase exhibiting anegative correlation between node degree and entropy, whilst the hub regimeexhibited a positive correlation (Fig. 4C). Veryinterestingly, however, increases in entropy were only observed for thehighest-degree hubs, with lower-degree hubs exhibiting decreases which weresurprisingly also of a larger magnitude (Fig. 4C). Thus,in networks with a scale-free or an approximate scale-free topology,overexpression of the highest degree hubs leads to an increase in the entropyrate. But increasing signaling flux through lower-degree nodes, even if ofrelatively high degree, leads to an overall reduction in the diffusion rate.

From the combined perturbation analysis, we can thus see that individualperturbations on an Erdos-Renyi graph, be they activations or inactivations (butboth causing a local reduction in entropy), invariably lead to a reduction inthe global entropy rate. This is in stark contrast to networks with a scale-freeor approximate scale-free topology, where we observe that gene activations canhave opposite effects on entropy rate depending on the degree of the activatingnodes.

Entropy rate increase in cancer requires a scale-free interaction networktopology

The previous perturbation analysis strongly supports the view that a scale-free,or near scale-free network topology, is important for the observed increasedentropy rate in cancer. To test this formally, we recomputed the entropy rate ofall 50 normal liver and 50 liver cancer samples, but now using an underlyingErdos-Renyi (ER) interaction network matched to the same size and averageconnectivity of the full PPI network. In order to faithfully preserve thecorrelation between gene expression and node degree of the PPI network, nodes ofthe ER network were ranked according to degree and gene expression valuesassigned according to their corresponding rank/centile in the original PPInetwork. Thus, this node mapping between the two networks preserves the observedrank correlation between differential expression and node-degree, allowing us toobjectively assess the importance of the scale-free property. Recomputation ofthe entropy rates of all 100 samples on the ER network revealed no significantdifference between normal and cancer, thus demonstrating that the observedentropy rate increase in cancer requires the scale-free property of theinteraction network (Fig. 5A). Supporting this further, weobserved, in two other matched normal-cancer RNA-seq expression sets from theTCGA, that the entropy was no longer higher in cancer when the PPI network wasreplaced with an equivalent ER graph (Fig.5B–C). In independent Affymetrix gene expression data, weobserved that the cancer-associated increase in the entropy rate was reducedupon computing entropy on an equivalent ER network, in three out of four studies(SI Appendix, fig. S6). Thus, in 6/7 data sets, there was a reduction in theentropy rate difference between cancer and normal tissue (Binomial, P = 0.008),supporting the view that a scale-free interaction topology is indeed necessaryfor the higher entropy signaling dynamics of cancer.

Entropy rate increase in cancer requires the scale-free topology of the PPInetwork:

(A) Boxplots of the entropy rate (SR) for the 50 normal liver and 50 livercancer samples as evaluated on the original full PPI network (left), as wellas on an equivalent Erdos-Renyi graph (middle). P-values are from aWilcoxon-rank sum test. Corresponding ROC curves and AUC values (right). (B)As A) but for TCGA RNA-Seq data from 27 colon cancers and 27 matchednormals. (C) As A) but for TCGA RNA-Seq data from 52 prostate cancers and 52matched normals.

Discussion

Signaling entropy, a measure of the overall uncertainty or promiscuity in signalingpatterns within a cellular sample, has been shown to be of biological significancein a variety of different contexts9,10,11. In cellulardifferentiation it provides a proxy to the energy potential (i.e. height) ofWaddington's epigenetic landscape, allowing the differentiation potentialof a sample to be assessed purely from its genome-wide transcriptomic profile10. Similarly, signaling entropy also provided us with a usefulframework in which to identify specific systems-level features characterisingcancer, one of which being the increased signaling promiscuity of cancer compared toits corresponding normal tissue9,10,11. This is important becausean increased signaling promiscuity could underlie the increased phenotypicplasticity of cancer, as observed e.g. by Pisco et al8.

In this work we aimed to obtain a deeper theoretical understanding as to (i) whysignaling entropy is increased in cancer and (ii) why it is such a robustdiscriminatory feature. We have here demonstrated that the increase in signalingentropy is driven by two factors. First, a subtle positive correlation betweendifferential gene expression and the degree of the corresponding proteins in the PPInetwork. This correlation amounts to hubs exhibiting preferential increases in geneexpression, whilst those genes exhibiting the most significant underexpression mappreferentially to low-degree nodes. Second, the observed increase of entropy incancer requires the scale-free (or near scale-free) topology characterising PPInetworks. Indeed, by considering a Poisson network with an identical rankcorrelation coefficient between differential expression and node-degree, we nolonger consistently observed a significant increased entropy rate in cancer (Fig. 5). Given the demonstrated biological significance of theentropy rate10,11, this last result thus exposes a deep connectionbetween the cancer phenotype and the underlying scale-free property of real PPInetworks. It suggests that if the degree distribution of a PPI network were Poisson,that the transcriptomic changes seen in cancer would not define a highly promiscuoussignaling regime. In other words, our data support the view that cancer“hijacks” the scale-free property of real signaling networksin order to facilitate increased signaling promiscuity and intra-tumourheterogeneity.

The novel insights described above also explain why the entropy rate provides such arobust discriminatory feature of the cancer phenotype. The robustness stems from thesubtle correlation between differential expression and node-degree. Although geneexpression data is notoriously noisy, there is generally speaking good agreementacross independent studies when comparing the changes in differential geneexpression between two marked phenotypes such as normal and cancer tissue27. Secondly, although current PPI networks only represent merecaricatures of the real interactions in a cell, the “hubness”of a protein is likely to be a very robust feature. Indeed, that a given protein hasexceptionally many interactions, thus defining a hub in a network, is likely to be avery robust feature, despite the fact that the specific interaction space of the hubmay contain many false negatives and false positives15. Thus, therelative robustness of differential expression and hubness drives the robustness ofthe observed correlation between differential expression and node degree, which inturn explains why increased signaling entropy is such a consistent feature of thecancer phenotype9,10. Given the robustness of signaling entropy as amarker of differentiation potency10, it is therefore tempting tospeculate that a subtle correlation between differential expression and node degreealso exists in the context of normal cellular differentiation. Furthermore, it willbe interesting to explore if the scale-free or near scale-free topology of PPInetworks is also a key element underlying the nature of pluripotency, multipotencyand terminal differentiation.

Although many previous studies have explored differential gene expression changes incancer and other diseases in relation to network topology28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37, most of these have eitherfocused on global topological properties, or on finding differential gene modules,or on studying absolute changes in differential expression. Indeed, a numberof studies agree in reporting that absolute differential expression correlatesnegatively with node degree, meaning that hubs exhibit, on the whole, much smallerchanges in expression between disease phenotypes28,30.Interestingly, however, relatively little attention has been paid to studying thedirectionality of differential gene expression in cancer in relation tonode degree. Here we have shown that there exists a subtle yet significantlypositive correlation between differential expression and protein-degree. On its own,the biological significance of this correlation is unclear. However, by interpretingthis correlation in the novel contextual framework of signalling entropy, we havehere shown how, in the context of real (near) scale-free networks, it could underpinthe increased phenotypic plasticity of cancer.

In summary, increased expression of oncogenic hubs, as well as reduced expression ofnetwork-peripheral tumour suppressor genes, in interaction networks characterised bya (near) scale-free topology, drives the high signaling entropy of cancer and couldthus underpin cancer's phenotypic robustness and plasticity. Furtherin-depth study of the complex interplay between local protein activity changes,their interaction network topology and the effect on signaling entropy iswarranted.

Methods

The protein protein interaction (PPI) network

We used a PPI network similar to that used in our previous publication38. Briefly, the human interaction network derives from the PathwayCommons Resource (www.pathwaycommons.org)15, which brings togetherprotein interactions from several distinct sources, including the Human ProteinReference Database (HPRD)14, the National Cancer Institute NaturePathway Interaction Database (NCI-PID) (pid.nci.nih.gov), the Interactome(Intact) http://www.ebi.ac.uk/intact/ and the Molecular InteractionDatabase (MINT) http://mint.bio.uniroma2.it/mint/. Protein interactions in thisnetwork include physical stable interactions such as those defining proteincomplexes, as well as transient interactions such as post-translationalmodifications and enzymatic reactions found in signal transduction pathways,including 20 highly curated immune and cancer signaling pathways from NetPath(www.netpath.org)39. The network focuses on non-redundant interactions, onlyincluded nodes with an Entrez gene ID annotation and on the maximally connectedcomponent thereof, resulting in a connected network of 8,434 nodes (uniqueEntrez IDs) and 303,600 documented interactions.

Normal and cancer tissue gene expression data sets

We focused on liver cancer because the associated normal tissue constitutes arelatively homogeneous mass of cells and thus the entropy rate is less likelyto be influenced by changes in tissue-type composition. We downloaded the level3 gene normalized RNA-Seq data from the TCGA (www.cancergenome.nih.gov) for amatched subset of 50 normal liver and 50 liver cancer samples. As validation, weconsidered an Affymetrix expression data set, consisting of 37 normal livers(including normal liver, cirrhosis and dysplasia) + 38 liver cancers25. To test generalisability, we also downloaded level 3 RNA-Seqgene normalised data from the TCGA for prostate cancer (52 cancers &52 matched normals) and colon cancer (27 cancers & 27 matchednormals). The other normal/cancer Affymetrix expression sets used have beendescribed previously10.

Construction of the sample specific stochastic matrix and entropyrate

The construction of the entropy rate follows the same method described in ourearlier work10,11. Briefly, we use the mass action principle todefine a stochastic matrix, pij, for each individual sample.In detail, let Ei denote the normalised expression level ofgene i in a given sample. For a given neighbour j ∈N(i) (where N(i) labels the neighbours ofi in the PPI), the mass-action principle means that the probabilityof interaction with j is approximated by the productEiEj, i.e. pij∝ EiEj. Normalising this to ensure that , we get for the stochasticmatrix,

, we get for the stochasticmatrix,

Clearly, if j∉ N(i), then pij = 0. From thisstochastic matrix one can then construct a local signaling entropy (LS)as

which reflects the level ofuncertainty or redundancy in the local interaction probabilities. We note thatthe above expression for the local entropy is not normalised so that the maximumpossible entropy depends on the degree (ki) of the node. Infact,

Finally, the signaling entropyrate, SR, is defined in terms of the stationary distribution (orinvariant measure) π of the stochastic matrix(πp = π), as24,40

i.e. this global signaling entropy rateis a weighted average of the local entropies LSi. We note thatalthough LSi is independent of the expression level of genei, that the gene's contribution to the entropy rate, i.e.πiLSi, is not. This is becauseπi will depend on the genei's expression level. In this work we refer to the termLSRi ≡πiLSi as the local entropy rateof gene i, whereas LSi is just the genei's local entropy.

The maximum entropy rate

Given a connected network, the maximum entropy rate, maxSR, over thenetwork does not depend on the gene expression data but only on the adjacencymatrix of the network. In fact, the maximum entropy rate is attained for astochastic matrix pij given by41

where v and  are the dominant right eigenvector and eigenvalueof the adjacency matrix A, respectively. Thus, it is important to notethat the configuration of maximal local entropy, i.e. the configuration wherefor each node i, pij =Aij/ki and LSi =log ki, is not the configuration of maximal globalentropy.

are the dominant right eigenvector and eigenvalueof the adjacency matrix A, respectively. Thus, it is important to notethat the configuration of maximal local entropy, i.e. the configuration wherefor each node i, pij =Aij/ki and LSi =log ki, is not the configuration of maximal globalentropy.

Perturbation simulation analysis

In what follows we describe the perturbation analysis performed onErdös-Renyi and scale-free networks, as well as on the full real PPInetwork described earlier. The calculation of the global signaling entropy rateis simplified significantly by the fact that the stochastic matrix defined byequation 1 has the detailed balance property, i.e. thestationary distribution obeys not only πp =π, but the more restrictive conditionπipij =πjpji. This detailed balancecondition can be shown to imply

where Fis a normalisation constant and  .

.

The initial configuration for the perturbative analysis is that of maximal localentropy for each node in the network, which as explained previously, does notrepresent the state of global maximum entropy. To construct this initialconfiguration we set the expression level of each gene/node to be identicalxi = x. Thus, in the initial configuration,xT,i = kix and from detailedbalance we obtain for the stationary distribution that

where V is the number of nodes in the networkand where  is the average degree. Asfar as the entropy is concerned, the local entropy of each node i issimply log ki, so the initial entropy rate is simply

is the average degree. Asfar as the entropy is concerned, the local entropy of each node i issimply log ki, so the initial entropy rate is simply

Now let us consider perturbing a genein the network by altering its expression level by an amount  . Without loss of generality we label theperturbed node by the index “1”, so that afterperturbation, the expression levels in the network are described by

. Without loss of generality we label theperturbed node by the index “1”, so that afterperturbation, the expression levels in the network are described by  . The new stationary distribution thenbecomes

. The new stationary distribution thenbecomes

For thelocal entropies, we get

where for i ∈N(1),  and

and  (j ≠ 1). Thus, the change in theentropy rate, ΔSR = SR′ −SRo, is easily computable following anyperturbation.

(j ≠ 1). Thus, the change in theentropy rate, ΔSR = SR′ −SRo, is easily computable following anyperturbation.

In the actual analysis, when performing activating perturbations, we set x= 2 and  , whilst, when modelinginactivating perturbations, we set x = 16 and

, whilst, when modelinginactivating perturbations, we set x = 16 and  . These values are typical for logged Affymetrix orIllumina data, with highly expressed genes normally exhibiting values largerthan 12 and lowly expressed genes showing values smaller than 4.

. These values are typical for logged Affymetrix orIllumina data, with highly expressed genes normally exhibiting values largerthan 12 and lowly expressed genes showing values smaller than 4.

References

Califano, A. Rewiring makes the difference. Mol Syst Biol 7, 463 (2011).

Dutkowski, J. & Ideker, T. Protein networks as logic functions in development and cancer. PLoS Comput Biol 7, e1002180 (2011).

Creixell, P., Schoof, E. M., Erler, J. T. & Linding, R. Navigating cancer network attractors for tumor-specific therapy. Nat Biotechnol 30, 842–8 (2012).

Schramm, G., Nandakumar, K. & Konig, R. Regulation patterns in signaling networks of cancer. BMC Syst Biol 4, 162 (2010).

Bandyopadhyay, S. et al. Rewiring of genetic networks in response to dna damage. Science 330, 1385–1389 (2010).

Ideker, T. & Krogan, N. J. Differential network biology. Mol Syst Biol 8, 565 (2012).

Csermely, P. & Korcsmaros, T. Cancer-related networks: a help to understand, predict and change malignant. Semin Cancer Biol 23, 209–12 (2013).

Pisco, A. O. et al. Non-darwinian dynamics in therapy-induced cancer drug resistance. Nat Commun 4, 2467 (2013).

West, J., Bianconi, G., Severini, S. & Teschendorff, A. E. Differential network entropy reveals cancer system hallmarks. Sci Rep 2, 802 (2012).

Banerji, C. R. et al. Cellular network entropy as the energy potential in waddington's differentiation landscape. Sci Rep 3, 3039 (2013).

Teschendorff, A. E., Sollich, P. & Kuehn, R. Signalling entropy: A novel network-theoretical framework for systems analysis and interpretation of functional omic data. Methods 67, 282–93 (2014).

Erdös, P. & Rényi, A. On random graphs. Pub Math 6, 290–297 (1959).

Barabasi, A. L. & Albert, R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science 286, 509–512 (1959).

Prasad, T. S., Kandasamy, K. & Pandey, A. Human protein reference database and human proteinpedia as discovery tools for systems biology. Methods Mol Biol 577, 67–79 (2009).

Cerami, E. G. et al. Pathway commons, a web resource for biological pathway data. Nucleic Acids Res 39, D685–D690 (2011).

Rolland, T. et al. A proteome-scale map of the human interactome network. Cell 159, 1212–26 (2014).

Albert, R., Jeong, H. & Barabasi, A. L. Error and attack tolerance of complex networks. Nature 406, 378–382 (2000).

Jeong, H., Mason, S. P., Barabsi, A. L. & Oltvai, Z. N. Lethality and centrality in protein networks. Nature 411, 41–42 (2001).

Serra-Musach, J. et al. Cancer develops, progresses and responds to therapies through restricted perturbation of the protein-protein interaction network. Integr Biol (Camb) 4, 1038–48 (2012).

Kim, J. et al. Robustness and evolvability of the human signaling network. PLoS Comput Biol 10, e1003763 (2014).

Wang, S. J., Wang, Z., Jin, T. & Boccaletti, S. Emergence of disassortative mixing from pruning nodes in growing scale-free networks. Sci Rep 4, 7536 (2014).

Teschendorff, A. E. & Severini, S. Increased entropy of signal transduction in the cancer metastasis phenotype. BMC Syst Biol 4, 104 (2010).

Haynes, C. et al. Intrinsic disorder is a common feature of hub proteins from four eukaryotic interactomes. PLoS Comput Biol 2, e100 (2006).

Gomez-Gardenes, J. & Latora, V. Entropy rate of diffusion processes on complex networks. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys 78, 065102 (2008).

Wurmbach, E. et al. Genome-wide molecular profiles of hcv-induced dysplasia and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 45, 938–947 (2007).

Barabasi, A. L. & Oltvai, Z. N. Network biology: understanding the cell's functional organization. Nat Rev Genet 5, 101–113 (2004).

Rhodes, D. R. et al. Large-scale meta-analysis of cancer microarray data identifies common transcriptional profiles of neoplastic transformation and progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 9309–9314 (2004).

Lu, X., Jain, V. V., Finn, P. W. & Perkins, D. L. Hubs in biological interaction networks exhibit low changes in expression in experimental asthma. Mol Syst Biol 3, 98 (2007).

Platzer, A., Perco, P., Lukas, A. & Mayer, B. Characterization of protein-interaction networks in tumors. BMC Bioinformatics 8, 224 (2007).

Komurov, K. & Ram, P. T. Patterns of human gene expression variance show strong associations with signaling network hierarchy. BMC Syst Biol 4, 154 (2010).

Komurov, K., White, M. A. & Ram, P. T. Use of data-biased random walks on graphs for the retrieval of context-specific networks from genomic data. PLoS Comput Biol 6, pii: e1000889 (2010).

Jonsson, P. F. & Bates, P. A. Global topological features of cancer proteins in the human interactome. Bioinformatics 22, 2291–2297 (2006).

Tuck, D. P., Kluger, H. M. & Kluger, Y. Characterizing disease states from topological properties of transcriptional regulatory networks. BMC Bioinformatics 7, 236 (2006).

Hudson, N. J., Reverter, A. & Dalrymple, B. P. A differential wiring analysis of expression data correctly identifies the gene containing the causal mutation. PLoS Comput Biol 5, e1000382 (2009).

Ulitsky, I. & Shamir, R. Identification of functional modules using network topology and high-throughput data. BMC Syst Biol 1, 8 (2007).

Chuang, H. Y., Lee, E., Liu, Y. T., Lee, D. & Ideker, T. Network-based classification of breast cancer metastasis. Mol Syst Biol 3, 140 (2007).

Yu, H., Kim, P. M., Sprecher, E., Trifonov, V. & Gerstein, M. The importance of bottlenecks in protein networks: correlation with gene essentiality and expression dynamics. PLoS Comput Biol 3, e59 (2007).

West, J., Beck, S., Wang, X. & Teschendorff, A. E. An integrative network algorithm identifies age-associated differential methylation interactome hotspots targeting stem-cell differentiation pathways. Sci Rep 3, 1630 (2013).

Kandasamy, K. et al. Netpath: a public resource of curated signal transduction pathways. Genome Biol 11, R3 (2010).

Latora, V. & Baranger, M. Kolmogorov-sinai entropy rate versus physical entropy. Phys Rev Lett 82, 520–524 (1999).

Demetrius, L. & Manke, T. Robustness and network evolution-an entropic principle. Physica A 346, 682–696 (2005).

Acknowledgements

A.E.T. is supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai Institute forBiological Sciences and the Max-Planck Gesellschaft.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.E.T. conceived and performed the research and wrote the manuscript. P.S. and R.K.helped with analytical computations. C.R.S.B. and S.S. contributed useful commentsto an earlier version of manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0International License. The images or other third party material in this article areincluded in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicatedotherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the CreativeCommons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder inorder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Teschendorff, A., Banerji, C., Severini, S. et al. Increased signaling entropy in cancer requires the scale-free property of proteininteraction networks. Sci Rep 5, 9646 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09646

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09646

This article is cited by

-

A unified resource and configurable model of the synapse proteome and its role in disease

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Relation extraction for biological pathway construction using node2vec

BMC Bioinformatics (2018)

-

Single-cell entropy for accurate estimation of differentiation potency from a cell’s transcriptome

Nature Communications (2017)

-

Large-scale gene co-expression network as a source of functional annotation for cattle genes

BMC Genomics (2016)

-

Epigenetic modulators, modifiers and mediators in cancer aetiology and progression

Nature Reviews Genetics (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.