Abstract

Simple models involving the gradual outboard accretion of material along curvilinear subduction zones are often inconsistent with field-based evidence. A recent study using 3-D geodynamic modelling has shown that the entrainment of an exotic continental fragment within a simple subduction system can result in a complex phase of growth. Although kinematic models based on structural mapping and high-resolution gravity and magnetic maps indicate that the pre-Carboniferous Tasmanides in southeastern Australia may have been subjected to this process, to date there has been little corroboration from crustal scale geophysical imaging. Here, we apply Bayesian transdimensional tomography to ambient noise data recorded by the WOMBAT transportable seismic array to constrain a detailed (20 km resolution in some areas) 3-D shear velocity model of the crust beneath southeast Australia. We find that many of the velocity variations that emerge from our inversion support the recently developed geodynamic and kinematic models. In particular, the full thickness of the exotic continental block, responsible for orocline formation and the tectonic escape of the back arc region, is imaged here for the first time. Our seismic results provide the first direct evidence that exotic continental fragments may profoundly affect the development of an accretionary orogen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Phanerozoic Tasmanides (or Tasman Fold Belt System) is located east of the locus of the Neoproterozoic Rodinia breakup1 and comprises an accretionary system that occupies the eastern third of the Australian continent2. The Tasmanides is the result of protracted accretionary growth outboard of the Archean and Proterozoic core of central and western Australia that occurred from the Early Cambrian through to the Jurassic. Its basement structure has proven difficult to study since vast Mesozoic-Cainozoic sedimentary and volcanic cover sequences obscure older outcrops and limit the power of direct observational techniques. The Lachlan Fold Belt, which forms the southern end of the Tasmanides, is thought to be particularly complex and may include an exotic continental block3,4, an amalgamation of multiple linear orogen parallel accretion events, a large orocline and several arc complexes2,3,5,6.

The evolution of accretionary orogens was recently addressed by Moresi et al.7 using 3-D geodynamic models, in which a lithospheric fragment impinges on a convergent continental margin. According to the numerical models, ingestion of the micro-continent resulted in slab retreat towards the proto-Pacific Ocean in an asymmetric southeast directed roll-back through eastern Victoria and northeast Tasmania, ultimately forming a large orocline. Although the 3-D numerical simulation correlates well with recent kinematic models of the Tasmanides2,3,4,8, which reconstructs the displacement of individual geological units over time, little evidence has been found for the location and 3-D geometry of key features such as the continental fragment. Many existing tomographic models of the Tasmanides only image the upper mantle and are unable to recover structures much below 100 km in size9,10, particularly in the crucial southern parts of the Lachlan Fold Belt. Several recent tomographic models offer higher resolution (~40–50 km) and are capable of imaging crustal structure11,12, but do not include Tasmania or Bass Strait, which form an important part of the orogenic system. The goal of this study is to use new ambient seismic noise data to image the 3-D structure of the crust in southeast mainland Australia, Bass Strait and Tasmania and test for direct evidence of a micro-continental fragment and associated structures as predicted by the model of Moresi et al.7

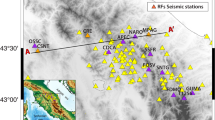

The ambient noise data used in this study comes from the WOMBAT transportable seismic array, the largest experiment of its kind in the southern hemisphere. Here, we use data from 582 of the stations in Tasmania (15 km separation), the adjacent mainland (50 km separation) and a number of the Bass Strait islands (Figure 1). Thus, a major challenge is that these datasets sample the crust at different scales and therefore are unlikely to produce good results if jointly inverted using conventional tomographic schemes based on regular parameterization11,13. Hence, we follow the same approach as Young et al.14 to jointly invert these multi-scale observations and constrain the 3-D shear wavespeed structure beneath the study area. Long term records of ambient seismic noise from simultaneously recording station pairs are cross-correlated and stacked to form inter-station empirical Green's functions15,16 (see Supplementary Fig. S1 online), from which Rayleigh-group speeds are obtained over a period range of 2 to 20 s. We then apply a novel two-stage transdimensional, hierarchical, Bayesian inversion approach17 that produces 2-D group velocity maps at different periods, from which a composite 3-D shear wavespeed model is obtained through a series of 1-D inversions12,14,18,19 (see Methods for more details and Supplementary Figs. S5 and S6 online for resolution tests and plots of uncertainty estimates respectively). The advantage of this approach is that the model resolution is variable and adapted to the irregular spatial distribution of the information provided by observations.

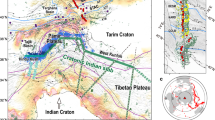

Tilt-filtered total magnetic intensity map (TMI) and location of seismic stations.

Base map comprises tilt-filtered total magnetic intensity (TMI) in grey-scale, overlain by semi-transparent pseudocolour TMI, with the spectrum from blue to red indicating the range from low to high anomalous magnetic field intensity respectively. Maps were created and magnetic data elaborated using Esri's ArcGIS platform (http://www.esri.com/software/arcgis). Major tectonic boundaries are outlined. Different colours represent different boundary ages. White triangles show the location of the WOMBAT stations used in this study. GC: Gawler Craton; CP: Curnamona Province; TFB: Thomson Fold Belt; DB: Darling Basin; SZ: Stawell Zone; HBZ: Hay-Booligal Zone; BZ: Bendigo Zone; SB: Selwyn Block beneath Melbourne Zone (MZ); WOMC: Wagga-Omeo Metamorphic Complex; MA: Macquarie Arc. mf: Moyston Fault; kf: Koonenberry Fault; af: Avoca Fault; hf: Heathcote Fault; gf: Governor Fault; bf: Bootheragandra Fault; if: Indi Fault; glf: Gilmore Fault Zone; tf: Tamar Fracture System.

We present period-dependent maps (Figure 2) and a horizontal slice taken from the final 3-D shear velocity model at 25 km depth (Figure 3). In general, we find that the group velocity maps are better discriminators of lateral structure at shallow to mid-crustal depths than the shear velocity model due to the non-uniqueness inherent in inverting group velocity for shear velocity. However, at greater depths, we find that the 1-D inversion process suppresses the effects of the thick sedimentary basins, thereby producing more reliable results in regions such as Bass Strait, where even the longer period maps show evidence of low sediment velocities. Although the tomographic results obtained here reveal a variety of anomalies across a range of depths, we predominantly focus on features that suggest the presence of an exotic continental block, a sedimentary basin resulting from rollback of the slab to the north of the micro-continent, extrusion of material from the overriding plate to the rear of the continental block, a tightly curved arc and arc magmas resulting from the re-establishment of subduction behind the accreted exotic block7.

Group velocity maps.

Maps of 6, 8, 12 and 16 s period Rayleigh wave group velocity. The tectonic boundaries from Figure 1 are shown. Acronyms are identical to those used in Figure 1, with the addition of BB and GB that indicate Bass and Gippsland basins respectively. White arrows point to the transition from Precambrian to Phanerozoic terranes. Peak sensitivity of the group velocity maps to shear wavespeed occurs at a depth approximately equal to the period in seconds multiplied by 1 km/s. Therefore, 6 s is equivalent to ~5–7 km in depth, 8 s to ~7–10 km, 12 s to ~10–15 km and 16 s to ~15–20 km. Maps were created and velocity data were elaborated using Esri's ArcGIS platform (http://www.esri.com/software/arcgis).

Horizontal slice from the tomographic shear-velocity model at 25 km depth.

White dashed line represents the near-surface extent of the Selwyn Block as suggested from geological constraints and aeromagnetic data. Red dashed line highlights the parts of the Selwyn Block boundaries that can be inferred from this study. Black dashed lines outline important features revealed by the tomographic model. Maps were created and velocity data were elaborated using Esri's ArcGIS platform (http://www.esri.com/software/arcgis).

The onset of terrain accretion over the eastern passive margin of Gondwana began in the Early Cambrian2, along what is now an arcuate-trending boundary that is clearly revealed by our model as an abrupt west-east transition from high to low velocities (white arrows in Figure 2). This prominent velocity change is congruent with the inferred east-dipping Escondida Fault, which is a good candidate for the expression of the transition from Precambrian to Phanerozoic crust in eastern Australia12,20 (Figure 2). The position of the fault is largely equivocal at the surface since it is buried by younger sediments and in some areas, particularly south of the Grampians Ranges, becomes challenging to identify using aeromagnetic data. However, the period-dependent maps in Figure 2 reveal the margin to be a major discontinuity, possibly east-dipping, that extends in depth to at least the mid-crust. It becomes a less dominant feature at 25 km depth (Figure 3), perhaps either failing to persist at depth or, more likely, passing down into crust of low velocity contrast and flattening in dip to be truncated by adjacent sub-parallel structures such as the Moyston Fault (mf). The Moyston Fault dips east21,22, and, together with a probable former northern extension adjacent to the Precambrian Curnamona Province (CP) - a position now overprinted by the younger Koonenberry Fault23 (kf) - appears to be a crustal penetrating fault that forms the western boundary of the Lachlan Orogen6 (Figures 1 and 2). In the central-upper part of the model we find a clear low velocity anomaly located in the upper crust, which correlates with the back-arc Darling and Newell basins (DB). According to Moresi et al.7, these were filled after the subduction zone became congested by the continental fragment and the slab started to tear. This crust is known to have undergone some thinning24, which may mean that the high velocities recorded in this area at 25 km depth are due to a shallower Moho (Figure 3). Alternative possible explanations include the presence of remnant underplated oceanic lithosphere; a lower crust dominated by Silurian back-arc rift-related volcanics, as seen in other Silurian basins in NSW25; or else a Proterozoic fragment detached from the supercontinent Rodinia during the break-up of Gondwana-Laurentia, which was eventually amalgamated in the accretionary terrane of the Lachlan Orogen2.

One remarkable feature that emerges from our tomographic model is a strongly curved region that is as much as ~0.5 km/s faster than the Darling Basin (SZ, Figure 2). This appears to mimic a distinct belt of deeply-sourced (minimum depth to top is ~1–5 km) magnetic highs, whose concentric, curved trends are revealed by the new tilt-filtered total magnetic intensity data26 (SZ, Figure 1). It is likely that this is the seismic expression of the northern end of the Cambrian Stawell Zone (SZ), an accretionary wedge that appears to be overprinted by a giant fold at its northern end27,28. This is one of the major fold hinges within the Lachlan Orocline. Another distinct low velocity area underlies the Hay-Booligal Zone (HBZ, Figure 2). By unfolding the Lachlan Orogen, it can be inferred that this area represents a piece of the Macquarie Arc7 (MA), trapped during right lateral strike-slip on the Bootheragandra Fault (bf). The eastern parts of the Lachlan Orocline, which according to the geodynamic model of Moresi et al.7 rolled-back and pivoted at the northern margin of the continental ribbon, correlate less well with velocity features in our model. This is partly because, with the exception of Bass Strait, the data coverage is limited to the onshore-regions in southeast Australia. The presence of the Bootheragandra Fault in the core of the eastern part of the Lachlan Orocline can be clearly inferred from our seismic models (Figures 2 and 3). According to Moresi et al.7, as the slab re-organizes and migrates behind the continental ribbon during roll-back and formation of the orocline, farther west the system is firmly controlled by the dextral strike-slip Bootheragandra Fault. This is clearly evident at all depths in our model and it is not only confined to the crust, but extends into the upper mantle, as recently revealed by teleseismic tomography29.

Re-establishment of slab retreat is known to be associated with emplacement of large volumes of basaltic magmas, accompanied by high-grade metamorphism and tectonic switching30. Adjacent to the Bootheragandra Fault, the eastern part of the tomographic model is extensively dominated by north-south trending high velocity anomalies, revealing a strong correlation between high temperature metamorphic belts, Ordovician volcanic arcs and granites with the velocity model. In particular, east of the Bootheragandra Fault, the Wagga-Omeo Metamorphic Complex is characterized by high velocities (WOMC, Figure 2), whereas the Macquarie Arc is identified as a low velocity belt.

The presence of three sedimentary basins in Bass Strait, two of which are clearly imaged in Figure 2 (marked as BB and GB), can be attributed to failed rifting associated with the diachronous break-up between Australia and Antarctica31. While continuity of western Tasmanian geology across Bass Strait into central Victoria can be inferred in outcrop and in aeromagnetic data32 (Figure 1), the thick basins make it difficult to assess the continuity of the Selwyn Block (SB) crust across Bass Strait at least at mid-upper crustal depths. More importantly, since the shape of the velocity anomalies found in Bass Strait at shorter periods resemble those of the sedimentary basins at depth, we have given consideration to the influence of low velocity areas in the uppermost part of the crust. The three sedimentary basins in Bass Strait are known to be deep; for example, Pilia et al.19 estimates that the Bass Basin may be up to 10 km thick, which might result in some vertical smearing and explain the reason why we still record a low velocity signature even at a period of 16 seconds (equivalent to about 15–20 km depth). On the other hand, this effect does not manifest in the 1-D inversion of group dispersion measurements. Furthermore, when attempting to identify the exact geographic extent of the Vandieland micro-continent, it has to be noted that a protracted tectonic evolution, characterized by a succession of geological events, has significantly modified the upper and mid crust post emplacement, thereby making interpretation at shallow depths difficult. However, a horizontal slice through the tomographic shear-velocity model at 25 km depth reveals for the first time the existence and lateral extent of the micro-continent (Figure 3) in the form of a distinct high velocity anomaly, which extends from Proterozoic northwestern Tasmania into mainland Australia (the region known as the Selwyn Block). Our new results correlate well with what has been inferred near the surface from aeromagnetic surveys and geological mapping and analysis3,4,32. The eastern margin of the continental fragment is clearly revealed by an easterly transition from high to low velocities in Tasmania, which may be caused by the juxtaposition of younger accreted material against Precambrian crust. At the surface, this juxtaposition occurs across the Tamar Fracture System (tf). Beneath Bass Strait, this transition becomes progressively narrower in a curvilinear path to southern mainland Australia, which appears to consistently match a transition from a stronger magnetic signature to the west to a more homogeneous and weaker response to the east.

The northern limit of the high velocity region that we associate with the Selwyn Block cannot easily be reconciled with existing models, since it does not continue as far northward into mainland Australia as the surface geology and deep seismic reflection data predicts. There are two possible reasons for this: (1) The Selwyn Block is compositionally heterogeneous and beneath Victoria it produces a seismic signature that is indistinguishable from that of surrounding rocks; (2) magma-induced heating of the lower crust associated with the recent Quaternary Newer Volcanics Province results in a localised region of lower velocity33,34 that overprints the signature of the Selwyn Block. In the latter case, it is interesting to note that the low velocity zone highlighted in Figure 3 almost exactly underlies the surface outcrop of the Newer Volcanics Province.

The main outcome of this study is that we find close agreement between the new seismic imaging results and key features postulated by the new dynamic model for accretionary margins as applied to the Tasmanides7. In particular, the continental fragment Vandieland, incorporated in the eastern margin of Gondwana during subduction accretion, has been detected. It occurs in the location predicted to have triggered a series of complex kinematic and dynamic processes, resulting in features such as a folded back-arc region and continental transform faulting, all of which make an appearance in the new seismic model. Our results are the first to demonstrate how a regional-scale shear-velocity model can geophysically image the full crustal thickness of ingested remnants of an exotic continental fragment at a former accretionary margin and provide evidence for associated orocline development. These findings have implications for the characterisation of cryptic colliders in other regions of the planet that have at some stage in their history hosted a similar tectonic setting, such as in other parts of Australia35, in the North American Cordilleras36 and in central Asia.

Methods

For each period of interest, the 2-D group velocity model is dynamically parameterised by a tessellation of Voronoi cells, which adapt throughout the course of the inversion to the spatially varying constraints provided by the data (see Supplementary Fig. S3 online). The parameterization is thus transdimensional in that the number, position, size and velocities of the cells are unknowns in the inversion and implicitly controlled by the data. The approach is also considered hierarchical since the level of noise is treated as unknown in the inversion process, resulting in a parsimonious trade-off between data noise and model complexity37. The inverse problem is tackled within a Bayesian framework that does not require explicit regularisation. The information is represented by probability density functions and the aim is to quantify the posterior probability density of the model parameters, conditional on the observed data.

The prior information represents our knowledge about the model before implementing the data constraints. In our case this is incorporated in a physically plausible and bounded range of the velocity field. The prior distribution is combined with the data likelihood distribution to construct a posterior solution. There is no analytical solution for the posterior and here it is approximated by efficiently sampling a range of model space using the reversible jump Markov chain Monte Carlo sampler38, which allows inference on both model parameters and model dimensionality (See Supplementary section S2 online for a more detailed description).

With the suite of the period-dependent group velocity maps, we can extract velocity values at a regular grid of points across the study area in order to generate 1-D group velocity dispersion curves. These can then be independently inverted for 1-D shear wave profiles by using the same technique described above and subsequently merged together to create a 3-D model. The model in this case is represented by a set of variable thickness layers, with the number, thickness and velocity of each layer free to vary during the inversion. The uncertainty estimates extracted from the 2-D posterior velocity distribution assessments (see Supplementary Fig. S6 online) are inherited for the 1-D inversions. This ensures that noisy measurements (i.e., large standard deviation values) will not unduly influence the final solution.

References

Direen, N. G. & Crawford, A. J. The Tasman Line: where is it, what is it and is it Australia's Rodinian breakup boundary? Aust. J. Earth Sci. 50, 491–502 (2003).

Glen, R. A. Refining accretionary orogen models for the Tasmanides of eastern Australia. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 60, 315–370 (2013).

Cayley, R. A. & Musgrave, R. J. A paradigm change - the giant Lachlan Orocline: consequence of microcontinent ingestion, stalled subduction and southeast-directed Siluro-Devonian subduction rollback superimposed on a single accreted Ordovician arc assemblage: the Lachlan Fold Belt of eastern Australia. AGU Fall Meet. Abstr. 1, 7 (2013).

Moore, D. H., Betts, P. G. & Hall, M. Towards understanding the early Gondwanan margin in southeastern Australia. Gondwana Res. 23, 1581–1598 (2013).

Collins, W. J. Hot orogens, tectonic switching and creation of continental crust. Geology 30, 535–538 (2002).

Cayley, R. A. et al. Crustal architecture of central Victoria: results from the 2006 deep crustal reflection seismic survey. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 58, 113–156 (2011).

Moresi, L., Betts, P. G., Miller, M. S. & Cayley, R. A. Dynamics of continental accretion. Nature 508, 245–248 (2014).

Cayley, R. A. Exotic crustal block accretion to the eastern Gondwanaland margin in the Late Cambrian–Tasmania, the Selwyn Block and implications for the Cambrian–Silurian evolution of the Ross, Delamerian and Lachlan orogens. Gondwana Res. 19, 628–649 (2011).

Rawlinson, N., Salmon, M. & Kennett, B. L. N. Transportable seismic array tomography in southeast Australia: Illuminating the transition from Proterozoic to Phanerozoic lithosphere. Lithos 189, 65–76 (2014).

Fishwick, S. & Rawlinson, N. 3-D structure of the Australian lithosphere from evolving seismic datasets. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 59, 809–826 (2012).

Arroucau, P., Rawlinson, N. & Sambridge, M. New insight into Cainozoic sedimentary basins and Palaeozoic suture zones in southeast Australia from ambient noise surface wave tomography. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37 (2010).

Young, M. K. et al. Crustal structure of the east Gondwana margin in southeast Australia revealed by transdimensional ambient seismic noise tomography. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 4266–4271 (2013).

Pilia, S., Rawlinson, N., Direen, N. G., Cummins, P. R. & Balfour, N. Structural controls on localized intraplate deformation and seismicity in Southern Australia: Insights from local earthquake tomography of the Flinders Ranges. J. Geophys. Res. B: Solid Earth 118, 2176–2190 (2013).

Young, M. K., Rawlinson, N. & Bodin, T. Transdimensional inversion of ambient seismic noise for 3D shear velocity structure of the Tasmanian crust. Geophysics 78, WB49–WB62 (2013).

Shapiro, N. M. & Campillo, M. Emergence of broadband Rayleigh waves from correlations of the ambient seismic noise. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31 (2004).

Shapiro, N. M., Campillo, M., Stehly, L. & Ritzwoller, M. H. High-resolution surface-wave tomography from ambient seismic noise. Science 307, 1615–1618 (2005).

Bodin, T. & Sambridge, M. Seismic tomography with the reversible jump algorithm. Geophys. J. Int. 178, 1411–1436 (2009).

Bodin, T. et al. Transdimensional inversion of receiver functions and surface wave dispersion. J. Geophys. Res. B: Solid Earth 117(B2) (2012).

Pilia, S. et al. Linking mainland Australia and Tasmania using ambient noise tomography: implications for the tectonic evolution of the eastern Gondwana margin. Gondwana Res. (2014), 10.1016/j.gr.2014.09.014.

Cayley, R. A. & Taylor, D. H. Grampians special map area geological report. Depart. of Natural Res. and Environ. (1997).

Cayley, R. A. & Taylor, D. H. Ararat 1:100 000 map area geological report. Geol. Surv. of Victoria, Report 115 (2001).

Korsch, R. J., Barton, T. J., Gray, D. R., Owen, A. J. & Foster, D. A. Geological interpretation of a deep seismic-reflection transect across the boundary between the Delamerian and Lachlan Orogens, in the vicinity of the Grampians, western Victoria. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 49, 1057–1075 (2002).

Greenfield, J. E., Musgrave, R. J., Bruce, M. C., Gilmore, P. J. & Mills, K. J. The Mount Wright Arc: A Cambrian subduction system developed on the continental margin of East Gondwana, Koonenberry Belt, eastern Australia. Gondwana Res. 19, 650–669 (2011).

Kennett, B. L. N., Salmon, M., Saygin, E. & Group, A. W. AusMoho: the variation of Moho depth in Australia. Geophys. J. Int. 187, 946–958 (2011).

Fergusson, C. L. Plate-driven extension and convergence along the East Gondwana active margin: Late Silurian-Middle Devonian tectonics of the Lachlan Fold Belt, southeastern Australia. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 57, 627–649 (2010).

Musgrave, R. & Rawlinson, N. Linking the upper crust to the upper mantle: comparison of teleseismic tomography with long-wavelength features of the gravity and magnetic fields of southeastern Australia. Explor. Geophys. 41, 155–162 (2010).

Hallett, M., Vassallo, J., Glen, R. & Webster, S. Murray-Riverina region: an interpretation of bedrock Palaeozoic geology based on geophysical data. Quarterly Notes of the Geol. Surv. of NSW 118, 1–16 (2005).

Rawlinson, N. et al. Complex continental growth along the proto-Pacific margin of East Gondwana. Geology 42, 783–786 (2014).

Rawlinson, N., Kennett, B. L. N., Vanacore, E., Glen, R. A. & Fishwick, S. The structure of the upper mantle beneath the Delamerian and Lachlan orogens from simultaneous inversion of multiple teleseismic datasets. Gondwana Res. 19, 788–799 (2011).

Foster, D. A. & Gray, D. R. Evolution and structure of the Lachlan Fold Belt (Orogen) of eastern Australia. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 28, 47–80 (2000).

Direen, N. G. Comment on “Antarctica-Before and after Gondwana” by SD Boger Gondwana Research, Volume 19, Issue 2, March 2011, Pages 335–371. Gondwana Res. 21, 302–304 (2011).

Cayley, R. A., Taylor, D. H., VandenBerg, A. H. M. & Moore, D. H. Proterozoic–Early Palaeozoic rocks and the Tyennan Orogeny in central Victoria: the Selwyn Block and its tectonic implications. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 49, 225–254 (2002).

Graeber, F. M., Houseman, G. A. & Greenhalgh, S. A. Regional teleseismic tomography of the western Lachlan Orogen and the Newer Volcanic Province, southeast Australia. Geophys. J. Int. 149, 249–266 (2002).

Davies, D. R. & Rawlinson, N. On the origin of recent intraplate volcanism in Australia. Geology, G36093–1 (2014).

Rosenbaum, G. Oroclines of the southern New England Orogen, eastern Australia. Episodes 35, 187–194 (2012).

Johnston, S. T. The Great Alaskan Terrane Wreck: reconciliation of paleomagnetic and geological data in the northern Cordillera. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 193, 259–272 (2001).

Bodin, T., Sambridge, M., Rawlinson, N. & Arroucau, P. Transdimensional tomography with unknown data noise. Geophys. J. Int. 189, 1536–1556 (2012).

Green, P. Trans-dimensional Markov chain Monte Carlo. Highly Struct. Stocha. Syst. 27, 179–198 (2003).

Acknowledgements

Major project support including that of S.P. was provided through the Australian Research Council grant LP110100256 and a CSIRO scholarship. We would like to thank Andreas Fichtner for his useful comments. Calculations were performed on the Terrawulf II cluster, a computational facility supported through the AuScope Australian Geophysical Observing System (AGOS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.P. provided group-wave traveltimes measurements for Bass Strait, computed the 2-D and 1-D inversions, assisted in interpretation and wrote most of the manuscript with N.R. N.R. and A.R. guided the study. R.C. co-wrote the paper and assisted in interpretation of the final model with N.D. R.M. provided the tilt-filtered TMI map. T.B. developed the rj-MCMC algorithm. M.Y. provided surface wave group traveltime measurements for mainland Australia and Tasmania. R.C. publishes with the permission of the Director of the Geological Survey of Victoria. R.M. publishes with the permission of the Director, Geological Survey of New South Wales, Division of Resources and Energy, NSW Department of Trade & Investment.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Pilia, S., Rawlinson, N., Cayley, R. et al. Evidence of micro-continent entrainment during crustal accretion. Sci Rep 5, 8218 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08218

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08218

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.