Abstract

Nacre realizes strength and toughness through hierarchical designs with primary “brick and mortar” structures of alternative arrangement of nanoplatelets and biomacromolecules and these have inspired the fabrication of nanocomposites for decades. However, to simultaneously solve the three critical problems of phase separation, low interfacial strength and random orientation of nanofillers for nanocomposites is a great challenge yet. Here we demonstrate that polymer-grafted graphene oxide sheets are exceptional building blocks for nanocomposites. Their liquid crystalline dispersions can be wet-spun into continuous fibres. Because of well-ordering and efficient load transfer, the composites show remarkable tensile strength (500 MPa), three to four times higher than nacre. The uniform layered microstructures and strong interlayer interactions also endow the fibres good resistance to chemicals including 98% sulfuric acid. We studied the enhancing effect of nanofillers with fraction in a whole range (0–100%) and proposed an equation to depict the relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A big problem for nanocomposites lies in phase separation, particularly at relatively high nanofiller fractions (> 10 weight %), due to the strong tendency of nanoparticle aggregation1,2. Several strategies have been proposed to surmount the obstacle, including layer by layer assembly (LBL)1, ice-templated method3 and vacuum assisted filtration4, since natural materials (e.g., nacre and bone) were found to be absence of phase separation even in the case of extremely large content of nanofillers (~95 volume % for nacre). Thus, various biomimetic composites have been obtained by alternative assembly of inorganic nanoplatelets (e.g., montmorillonoid (MTM), aluminum oxide and silicate) and organic polymers (e.g., polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and polymethyl methacrylate), approaching nacre-comparable performance5. Despite their exquisite microstructures, the non-covalent, weak interfaces between nanofillers and polymers impede the further progress of nacre-mimics. Full cross-linking could significantly improve the mechanical strength of nanocomposites, but makes the material rather brittle (ultimate strain 0.33%)1.

Due to its high aspect ratio and amazing mechanical properties, graphene and its derivatives are also under active investigation in nanocomposite field6. However, such composites7,8,9 (< 210 MPa) can hardly satisfy the theoretical prediction that declared ultrahigh mechanical strength10, due to the difficulty in efficiently transferring the property of single sheet to that of macroscopic composites. Accordingly, to access biomimetic composites that completely exceed biological layered materials in strength, toughness and scale, original designs from synthesis of building blocks to assembly method are needed.

Here we propose a “bottom up” strategy to make biomimetic materials by wet spinning assembly of polymer-grafted graphene oxide (PgG) building blocks. Because of the covalent and uniform immobilization of polymer chains on the surface of individual graphene oxide (GO) sheets, local phase separation is fundamentally avoided and strong interfacial interaction is introduced simultaneously. PgG sheets are highly dispersible in organic solvents and form liquid crystals (LCs) above a critical concentration, paving the way for producing highly ordered composites in large-scale. Wet-spinning the PgG LCs gives birth to continuous biomimetic fibres with ultrahigh strength (500 MPa), good toughness (7.8 MJ·m−3) and impressive Young's modulus (18.8 GPa). The volume fraction of GO in the composites can be easily tuned in a wide range (25–88%) by controlling the grafting polymer amount, which enables us to investigate the nanofiller-enhancing effect with fraction in a range of 0–100%. Additionally, the robust PgG fibres show remarkable chemical resistance, including 98% sulfuric acid, due to their compact layered structures and strong interlayer interactions, promising broad practical applications.

Results

Synthesis of PgG building blocks

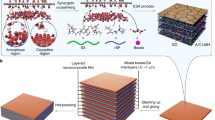

Figure 1 shows the preparation protocol for the biomimetic composites. Three steps are included: (i) synthesis of building blocks of PgG sheets, (ii) formation of colloidal LCs and (iii) spinning assembly into macroscopic fibres. We chose GO as the two dimensional (2D) backbone of adhesive building blocks, because of its exceptional attributes such as superior mechanical property, high aspect ratio (103–104), chemical activity of functional groups including in-plane double bonds and commercially large-scale availability11,12. Polymer chains were then covalently bonded onto the nanoplatelets through in situ free radical polymerization of vinyl monomers (e.g., glycidyl methacrylate, GMA)13. After removing the ungrafted polymers from the reaction system by cycles of centrifugation, decanting and redispersing for at least ten times, we obtained the neat PgG building blocks. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) measurements showed that typical PgGs were featured with uniform and dense clusters and held an average thickness of 3.5 nm (Fig. 2a, b), much higher than pristine GO sheets (average thickness <t> 0.8 nm). The average width (<w>) of PgG sheets was 0.8 μm with polydispersity (relative standard deviation) of 26% (Fig. S1). By adjusting the polymerization time (1, 1.5, 5, 18 h), we obtained a series of PgGs with desired grafted polymer contents, denoted as PgG-1 (the volume fraction of GO, fGO, 0.88), PgG-2 (fGO 0.62), PgG-3 (fGO 0.34) and PgG-4 (fGO 0.25) (Supplementary Table S1 and Fig. S2). Notably, control experiments demonstrated that the ungrafted or adsorbed polymers were completely removed from GO surfaces13.

Synthesis of PgG building blocks and wet spinning assembly approach to PgG fibres.

(i) Synthesis of PgG building blocks by in situ free radical polymerization of GMA in the presence of GO, followed by removing ungrafted polyGMA through cycles of centrifugation, decanting and redispersion. (ii) Formation of LC spinning liquid with spontaneous alignment of PgG sheets above the critical concentration. (iii) Wet spinning of PgG LCs into continuous fibres with B&M microstructures.

PgG building blocks and their alignment in solution.

(a), (b) AFM images of PgG sheets deposited from their DMF suspensions onto a mica substrate. (c), (d) POM images of PgG sheets in DMF with ϕ 0.32% and in chloroform with ϕ 0.39%. (e–g) 2D SAXS patterns of PgGs in DMF with ϕ 0.19% (e), 0.32% (f) and 0.66% (g). (h) SAXS profiles for PgG sheets in DMF with gradient ϕ of 0.19%, 0.32%, 0.55%, 0.66%, 0.76%, from bottom to top. (i), (j) Cryo-SEM images of PgG LC featured with lamellar ordering.

LC of PgG dispersions

The grafted polymers can sterically stabilize particles in polymer-favored solvents, resulting from an osmotic and configuration entropy effect14. PgG sheets were highly dispersible in organic solvents such as the less polar chloroform (relative dielectric constant εr, 4.81) and the polar tetrahydrofuran (εr, 7.58), dichloromethane (εr, 8.93), acetone (εr, 20.7) and dimethylfomamide (DMF) (εr, 36.7), no longer dispersible in water (εr, 80.4) where pristine GO is well dispersed. This in turn confirmed the efficient polymer functionalization on GO surfaces. According to Onsager's theory, the gain of free volume entropy as compensation for the loss of orientation entropy underlies the LC formation15. Similar to the LC behaviour of aqueous GO, PgG dispersions showed significant birefringence under polarized optical microscope (POM) in organic solvents (Fig. 2c, d), owing to their high asymmetry and fine dispersity. On the contrary, pristine GO would heavily aggregate in chloroform (Supplementary Fig. S3h). We observed the spreading Schlieren textures (Fig. 2c), implying that stable nematic phase formed at a low volume fraction (ϕ 0.32%). The observed isotropic-nematic transition range (0.14–0.32%, Supplementary Fig. S3) was close to that of theoretic prediction (0.22–0.31%) for a model of polydispersed infinitely thin platelets (Supplementary text)16. At high concentrations, the PgG dispersions involved vivid textures of aligned strips (Fig. 2c, d), which could be assigned to a periodic distortion structure17. Synchrotron small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) gave quantitative structure information on the LC dispersions. The anisotropy of SAXS 2D patterns became more pronounced with increasing ϕ (Fig. 2e–g), which was a sign of higher degree of orientation. As ϕ ≥ 0.32%, diffuse scattering peaks appeared in the SAXS profiles, indicating a local lamellar ordering of PgGs in the LC dispersions18. The calculated interlayer spacing (d = 2π/q, where q is the scattering vector) decreased from 86 nm to 57 nm as ϕ increased from 0.32% to 0.76%, which showed a deviation from the theoretical one dimensional swelling/deswelling behavior of 2D colloidal LCs (Fig. 2h)19,20. The deviation may be ascribed to the polydispersity of lateral size and the irregularity of shape of PgG. The lamellar-like structures of PgG LCs were directly visualized by cryo-scanning electric microscopy (cryo-SEM) (Fig. 2i, j). Additionally, chirality with random sign of dichroic ratio for PgG dispersions similar to aqueous GO19 was also observed (circular dichroism spectra data in Supplementary Fig. S4). PgG dispersions are also an example for chiral LC comprising achiral molecules21.

Wet-spinning assembly of PgG fibres

The pre-alignment in macromolecular LC decreases the extrusion force needed in the spinning process and affords much less defects in the produced fibres, as in the cases of spider silk, commercial Kevlar fibres and carbon nanotube (CNT) fibres22,23. Following the discovery of GO LC behaviors24,25,26,27 and the realization of continuous graphene fibres by wet-spinning assembly strategy19, various GO and GO-based composite fibres have been obtained28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. For their high solubility (> 30 mg·mL−1) and LC behavior, PgG sheets were directly used as building blocks to make composite fibres by industrially viable wet spinning technique (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S5). The PgG LC was smoothly injected into a rotating coagulation bath through a spinneret. The freshly fashioned gel fibres showed vivid birefringence under POM (Fig. 3a), indicating the alignment of PgG building blocks. The shrinking of the gel fibre into solid fibre was confirmed by in situ POM observations (Fig. 3b). A dried five meter-long PgG fibre was collected on a scroll after being washed with water (Fig. 3c). The fibres were woven into textiles and tied into knots, demonstrating their good flexibility, which is very important to actual applications (Fig. 3d).

Formation and structures of PgG fibres.

(a), (b) POM images of freshly wet spun gel PgG fibres and the evolution to solid fibres. (c) A five meter-long PgG fibre collected on a scroll. (d) Photograph of a hand-woven textile and SEM image (inset) of a knot made of PgG fibres. (e–h) SEM images of the rounded morphology (e), fracture sections in a top-view direction (f) and in a tilt viewing direction (g) and wrinkle surface (h) of a PgG fibre.

The microstructures of PgG fibres were characterized by SEM (Fig. 3e–h). The ruptured cross section showed rounded morphology for a fibre of 15 μm in diameter (Fig. 3e). Under zooming in, highly uniform layered structures were observed, revealing the “brick & mortar” (B&M) architecture of PgG fibres. Staggered blocks with layered structure were seen in the fibre cross-section, as indicated by the blue lines in Fig. 3f. The stagger structures probably inherited from the multi-domains in the LC spinning doping (Supplementary Fig. S3i–k). The formation of accordion-like structures was probably driven by the liquid surface tension during drying, as in the case of dehydration process of nematic aqueous GO droplet26. Such structures may result in out-of-plane interlocking that favours the fibre strength. Long-range ridges along the fibre axis indicate the coherent buckling behaviour of PgG sheets during the drying process (Fig. 3h).

Mechanical properties of PgG fibres

The difficulty in translating the excellent intrinsic mechanical properties (i.e. strength, stiffness) of individual nanofillers into those of macroscopic bulk materials made the mechanical performance of nanocomposites remain stagnant for a long time. Problems like aggregation of particles violate the load transfer, through a decrease of contact interface40,41. The interfacial strength also imposes restrictions on the load that can be transferred, which is a hierarchical issue in terms of chemical interactions42,43,44, macromolecular conformation2,45 and surface morphology46. Having delicate layered structures and enhanced interfacial strength, PgG-2 fibres held a tensile strength (σc) of 440 ± 60 MPa (the best value was 500 MPa) and a toughness of 6.9 ± 0.9 MJ·m−3 or 5.1 ± 0.7 J·g−1 (the fibre density was measured as 1.34 g·cm−3) (Fig. 4a).

Mechanical properties of PgG fibres.

(a) Tensile test curves of PgG-2 (1), neat GO (2) and PmG (3) fibres. The inset shows the stagger arrangement of PgG building blocks in the fibre and covalent bonding between polymer chains and GO sheets. (b) Relationship between tensile strengths and fGO of PgG fibres (squares). The blue curve is generated from equation (1). (c) Tensile strengths and toughness for artificial and natural layered materials. PDDA indicates poly(diallydimethylammonium chloride). (d) Enhancing coefficient (σc/σm) for typical fillers in polymer-based composites. The red symbols denote filler volume fraction above 10% and the blue ones below 10%. The star-shaped symbols represent PgG-2 and PmG fibres.

Our PgG-2 fibre possessed much higher absolute strength than nacre (~150 MPa)47 and other biomimetic materials including graphene-based and MTM-based layered-structure materials (80–109 MPa)48,49 and it is also stronger than the chemically crosslinked artificial nacre1 (400 ± 40 MPa) (Fig. 4c). Significantly, the specific strength (strength/density) (373 kN·m·kg−1) of our biomimetic PgG composites is even higher than those of Bainite (321 kN·m·kg−1), titanium (288 kN·m·kg−1), stainless steel (254 kN·m·kg−1), aluminium-alloy (214 kN·m·kg−1) and magnesium-alloy (158 kN·m·kg−1). The PgG fibres are nearly 2.5 times as strong as neat GO fibres (205 MPa), demonstrating the glue effect of polymer layer in the biomimetic composites. The σc of PgG-2 fibre was ~ 733 folds higher than that of neat polymer fibre (0.6 MPa for polyGMA). This is the best enhancing coefficient (σc/σm, where σm is the tensile strength of polymer) among all nanocomposites based on the ever best fillers such as CNTs (1.25–21)50,51, MTM (1.4–10.0)48,52, graphene (1.2–2.6)7,53, glass fibres (~2.4) and Kevlar fibres (~2) (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Table S2). This result may indicate in turn the highly efficient load transfer between nanofillers and polymer matrix in our composites because of their covalent linkage and homogeneous alignment. Therefore, we consider such composites integrating ultrahigh strength, good toughness and scalable productivity as the next generation of nacre-mimetic materials.

To further demonstrate the advantages of PgG fibres built from covalently bonded fillers and matrix, we also spun fibres from the blending of GO and polymer with the same fGO of PgG-2 (denoted as PmG fibres). PmG fibres showed a tensile strength of 101 ± 10 MPa (Fig. 4a). PgG-2 fibres are about 5 times the tensile strength of PmG fibres. This giant enhancement for the case of covalent bonding is mainly ascribed to the extra interfacial fracture energy that is 2.2 mJ·m−2, calculated by multiplying the rough density of polymer chains on PgG-2 (3788 chains μm−2, calculation details in Supplementary Table S1) and carbon-carbon single bond energy (346 kJ·mol−1)54.

Compared with neat GO fibres (σ 205 MPa), polymers can endow extra covalent bonding and van der Waals interaction between the ultrastiff nanofillers. We assume additional shear strength (σp) of grafted polymers to the original shear strength between neighboring neat GO sheets (σGO) to illustrate the grafted polymer effect. Based on the tension shear chain (TSC) model55 that is prevalently used to theoretically describe the mechanical properties of nanocomposites, the strength of our PgG composites σc is written as follows:

where w and t are the width and thickness (~0.8 μm and 0.8 nm) of GO sheets. The shear strength between PgG sheets is mainly contributed by polymer glue effect (σp) and interaction between GO sheets (σGO). The shear strength offered by polymer, σp(1 − fGO), is proportional to its volume fraction (1 − fGO) and the shear strength offered by GO sheets, σGOfGO, proportional to fGO. Based on the data of PgG-2 and neat GO fibres, σp and σGO were calculated to be 3.08 MPa and 0.4 MPa. This σp resulted from our macroscopic material is ~ 30% larger than the nanomechanics-measured interfacial stress before slippage (~2.3 MPa) between single graphene sheet and polymethyl methacrylate matrix56, suggesting the covalent bonding effect. Thus equation (1) re-written as σc = (1540−1340 fGO)fGO defines σc as a function of fGO, which is depicted as a curve shown in Fig. 4b. According to the curve, σc increases rapidly with increasing fGO below 0.4 and reaches a plateau at 0.45–0.65 and then drops quickly above 0.7. The trend can be explained as follows: for composites with relatively low fraction of nanofillers, σc is mainly determined by the enhancing effect of nanofillers; at a certain fraction, σc goes to a maximum due to the optimization of the two factors of shear strength and nanofiller fraction; above the critical fraction, the trend of σc is essentially influenced by the decrease of shear strength.

To examine the validity of equation (1), we synthesized PgGs with various fGO (0.25–0.88) and thus obtained the corresponding series of PgG fibres. Their tensile strengths are also shown in Fig. 4b. The experimental σc increases dramatically and achieved the highest value at around 0.62 (PgG-2 fibre) and then decreases notably upon the increase of fGO, which is in close agreement with equation (1). Optimized amount of polymer glue was also reported in the case of PVA-enhanced CNT yarns57. This is the first time to study the enhancing effect of nanofillers in a large-range of fraction (25–88%) and we discover that the critical fraction is actually very high (> 50%) for nanocomposites without phase separation. This finding breaks the rule of conventional nanocomposites that allows a very low critical fraction (< 10%) due to the strong aggregation of nanofillers. Despite complex assembly protocols were previously developed to fabricate layered-structured composites with high fraction of platelets, the enhancing effect as a function of filler fraction was never reported, likely due to their fractions were difficult to be tuned in a large range. Hence, such a new principle lights the design multifunctional and high performance nanocomposites.

Given that the theoretical in-plane modulus of graphene (E) is about 1000 GPa and σc of PgG fibres is 500 MPa and that most of stress is undertaken by the stiff graphene sheets in the nanocomposites, the strain (ε) of graphene sheets at breakage is at the order of magnitude of 0.05% (ε = σc/E), far smaller than the measured breakage strain of composites (3–10%). So PgG fibres take a ductile fracture with sliding mechanism (Supplementary Fig. S7). SEM observations showed emerging PgG sheets at the fracture section of composites indeed, further confirming the pullout nature of failure mechanism (Fig. 3g). According to the TSC model, there exists a critical aspect ratio (Sc) to predict the operative fracture mode52, Sc = 2σ/τ, where σ is the filler strength and τ is the interlayer shear strength. As the aspect ratio is above Sc, the material goes a brittle fracture, otherwise a ductile fracture. For σ = 130 GPa (tensile strength of graphene) and τ = 1.4 MPa (estimated shear strength between building blocks in PgG-2 fibre), Sc should be ~ 1.8 × 105, which is around two orders of magnitude higher than the actual average aspect ratio of GO in PgG (<w>/<t> = 1000). So this calculation result indicates a pull-out fracture mechanism for our composites.

Cyclic loading experiments manifested the damping behaviour of PgG fibres (Supplementary Fig. S6). A portion of energy (16.9%, 16.7%, 14.4%, 8.6% and 9.6%, respectively from cycle 1 to cycle 5) was stored, expressed as the area between loading and unloading curves in one cycle. The Young's modulus increased about 44% after five cycles, indicating the self-reinforcing behaviour of PgG fibres49. Non-covalent linkage between building blocks enables them self-adaptive re-arrangement under tension to better fit microstructures.

After reduction by hydroiodic acid58, PgG fibres held an electric conductivity of 186 S/m (Supplementary Fig. S11) and ~ 8% increase in tensile strength, probably due to the reduction of interlayer distance59.

Chemical resistence of PgG fibres

Chemical resistance is of significance for high performance fibres applied in harsh environment. So we measured the chemical resistance of our PgG fibres against organic solvents and strong acids. The PgG fibres held ~ 100% retention of tensile strength after being immersed in ethanol, acetone, ethyl acetate, n-hexane, tetrachloromethane (measured immediately after being taken out from the solvents) (Supplementary Fig. S8). Especially, our PgG fibres only swell slightly in 98% sulfuric acid and kept their full morphology even after immersion for one month (Fig. 5a). The H2SO4-immersed PgG fibres showed ~ 50% retention of tensile strength without being washed and recovered to ~ 100% after being washed with ethanol and dried (Fig. 5b). This superb chemical resistance may be ascribed to four factors: chemical inertia of constituents, ultrastrong interactions between large building blocks, highly ordered layered-architecture and hierarchical structures. Such attributes enable the slightly expanded interlayer of building blocks to readily recover to original compact structures after being washed and dried, as demonstrated by their highly ordered B&M architecture (SEM images in Fig. 5c, d). The chemical resistance nature of PgG fibres is very important to their practical applications. Raman spectra also confirmed the inertia of GO in PgG fibres to 98% sulfuric acid (Supplementary Fig. S10). On the contrary, those commercial strong fibres such as Kevlar, cotton and Nylon 6 fibres were completely dissolved within several minutes in 98% sulfuric acid (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. S9).

Chemical resistance of PgG fibres.

(a) Photographs of PgG fibre (left) and Kevlar fibre (right) immersed in 98% sulfuric acid for 1 month and 3 minutes, respectively. (b) Tensile strength retention of PgG fibres immersed in 98% sulfuric acid for different time. (c), (d) SEM images of cross section of a PgG fibre after 98% sulfuric acid immersion.

Discussion

The preparation of PgG fibres set a good example for fabrication of nacre-mimic materials with a large range of filler fraction (0–100%), which is significant for the development of theoretical modelling and computer calculation for nanocomposites and bio-mimics. Moreover, the corresponding rheology of such system is also a new area to be exploited. By comparison, the traditional blending way often leads to the problem of phase separation when the filler fraction is up to 10%. The long used LBL method can achieve the uniform alternative arrangement of fillers and macromolecules, but the absorbed amount of polymer is generally determined by its adsorption attributes at the interface of inorganic particles and solvents1,60. So it is hard to tune the filler fraction in the composites for the non-covalent adsorption methodology.

From the point of view of components, our covalent-grafting strategy can be readily extended to other colloids (e.g. MTM, nontronite and ceramic particles) and polymers (e.g., nylon, polyethylene terephthalate, light-emitting polymers, electrically conductive polymers and biomacromolecules), paving the way to multifunctional and high performance composites with tailored properties in a wide range of polymer fraction.

In summary, we have proposed a new strategy to fabricate strong, tough and scalable nacre-mimetic fibres by wet spinning assembly of building blocks of polymer-grafted GO. The covalent immobilization between GO and polymers avoids phase separation which always happens in the case of simple blending and simultaneously endows high interfacial strength. The polymer grafting also offered the building blocks good solubility in common organic solvents, allowing their formation of LCs. Both the covalent bonding and the pre-alignment in the LC liquids contributed to compact and uniform B&M structures and thus ultrahigh mechanical strength of composite fibres. Due to the absence of filler aggregation, we achieved nanocomposites with desired content of fillers and then discovered the critical filler fraction approaching the maximum of composite strength, which is much higher than the long accepted value for nanocomposites. A record of enhancing coefficient was obtained in our composites, one to two orders of magnitude higher than those of reported composites. The macroscopic assembled fibres showed remarkable chemical resistance, including 98% sulfuric acid, due to their compact microstructures and strong interlayer interaction. Such versatile fibres are widely useful in many fields like functional textiles, supercapacitors and pollution treatments.

Methods

Synthesis of PgG

Well-dispersed GO was synthesized from natural graphite powder (40 μm) using a modified Hummers method53. Neat PgG building blocks with given amount of grafted polyGMA were synthesized by free radical polymerization of GMA in the presence of GO according to the protocol previously reported13. The molar ratio of monomer (GMA) and initiator (azodiisobutyronitrile) is 200:1. After certain reaction time (1, 1.5, 5, 18 h), the reaction was quenched. The resultant solution underwent at least ten cycles of centrifugation, decanting and redispersion in DMF, to get the PgG solution without free polyGMA and possible absorbed polyGMA on GO. In a controlled experiment, GO was mixed with polyGMA in solution. After cycles of centrifugation, decanting and redispersion, both AFM and TGA can show the nearly absence of polyGMA, indicating that the free polyGMA and possible absorbed polyGMA can be washed away from GO in the cycles, i.e. only the covalently grafted polyGMA can survive the repeated washing process in our case. In addition, the weight percentage of polyGMA in PgG increases with the increase polymerization time. These observations are strong evidence for the grafting nature in our in situ free radical polymerization strategy.

Wet spinning of PgG fibres

The resulting PgG dispersions in DMF were concentrated to around 20 mg·mL−1 for obtaining the LC-state spinning liquid. The PgG LCs were loaded into a 5 ml plastic syringe with a spinning nozzle (PEEK tube with diameter of 250 μm) and injected into a rotating coagulation bath of 5 wt% CaCl2 in water-ethanol by an injection pump. After coagulation for 10 minutes, the gel fibres were drawn out, washed with water to remove extra ions and dried at 80°C in vacuum for 24 h, affording final PgG fibres.

Characterization

AFM images were taken in the tapping mode carrying out on a Nanoscope IIIa, with samples prepared by spin-coating sample solutions onto freshly cleaved mica substrates. POM observations were performed with a Nikon E600POL using a bright field transmission-mode and the liquid samples were squeezed into the home-made planar cells sealed by glass cement (1.5 mm in thickness) for observations. SAXS tests were carried out in Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF), Shanghai, China, using a fixed wavelength of 0.124 nm, a sample to detector distance of 5 m and an exposure time of 600 seconds. The 2D scattering patterns were collected on a CCD camera and the curve intensities vs. q were obtained by integrating the data from the patterns. Cryo-SEM images were taken on a Hitachi S3000N equipped with a cryo-transfer. Circular dichroism spectra were collected on a Bio-Logic MOS-450 spectrometer and the samples were injected into the quartz cuvette with a light path length of 0.5 cm. Common SEM images were taken on a Hitachi S4800 field-emission SEM system. Mechanical property tests were carried on a HS-3002C at a loading rate of 10% per minute.

References

Podsiadlo, P. et al. Ultrastrong and stiff layered polymer nanocomposites. Science 318, 80–83 (2007).

Ajayan, P. M. & Tour, J. M. Materials science: nanotube composites. Nature 447, 1066–1068 (2007).

Deville, S., Saiz, E., Nalla, R. K. & Tomsia, A. P. Freezing as a path to build complex composites. Science 311, 515–518 (2006).

Cheng, Q. F., Wu, M. X., Li, M. Z., Jiang, L. & Tang, Z. Y. Ultratough artificial nacre based on conjugated cross-linked graphene oxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 3750–3755 (2013).

Wang, J. F., Cheng, Q. F. & Tang, Z. Y. Layered nanocomposites inspired by the structure and mechanical properties of nacre. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 1111–1129 (2012).

Kim, H., Abdala, A. & Macosko, C. Graphene/polymer nanocomposites. Macromolecules 43, 6515–6530 (2010).

Wang, X., Bai, H., Yao, Z., Liu, A. & Shi, G. Q. Electrically conductive and mechanically strong biomimetic chitosan/reduced graphene oxide composite films. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 9032–9036 (2010).

Liang, J. et al. Molecular-level dispersion of graphene into poly(vinyl alcohol) and effective reinforcement of their nanocomposites. Adv. Funct. Mater. 19, 2297–2302 (2009).

Kou, L. & Gao, C. Bioinspired design and macroscopic assembly of poly(vinyl alcohol)-coated graphene into kilometers-long fibres. Nanoscale 5, 4370–4378 (2013).

Compton, O. C. et al. Tuning the mechanical properties of graphene oxide paper and its associated polymer nanocomposites by controlling cooperative intersheet hydrogen bonding. ACS Nano 6, 2008–2019 (2011).

Geim, A. K. & Novoselov, K. S. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 183–191 (2007).

Zhu, Y. W. et al. Graphene and graphene oxide: synthesis, properties and applications. Adv. Mater. 22, 3906–3924 (2010).

Kan, L. Y., Xu, Z. & Gao, C. General avenue to individually dispersed graphene oxide-based two-dimensional molecular brushes by free radical polymerization. Macromolecules 44, 444–452 (2010).

Vrij, A. Polymers at interfaces and the interactions in colloidal dispersions. Pure Appl. Chem. 48, 471–483 (1976).

Onsager, L. The effects of shape on the interaction of colloidal particles. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 51, 627–659 (1949).

Bates, M. A. & Frenkel, D. Nematic-isotropic transition in polydisperse systems of infinitely thin hard platelets. J. Chem. Phys. 110, 6553–6559 (1999).

Srajer, G., Fraden, S. & Meyer, R. Field-induced nonequilibrium periodic structures in nematic liquid crystals: nonlinear study of the twist Frederiks transition. Phys. Rev. A 39, 4828 (1989).

Michot, L. et al. Liquid–crystalline aqueous clay suspensions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 16101–16104 (2006).

Xu, Z. & Gao, C. Graphene chiral liquid crystals and macroscopic assembled fibres. Nat. Commun. 2, 571 (2011).

Gabriel, J. et al. Swollen liquid-crystalline lamellar phase based on extended solid-like sheets. Nature 413, 504–508 (2001).

Sekine, T. et al. Spontaneous helix formation in smectic liquid crystals comprising achiral molecules. J. Mater. Chem. 7, 1307–1309 (1997).

Behabtu, N., Green, M. J. & Pasquali, M. Carbon nanotube-based neat fibres. Nano Today 3, 24–34 (2008).

Vollrath, F. & Knight, D. P. Liquid crystalline spinning of spider silk. Nature 410, 541–548 (2001).

Xu, Z. & Gao, C. Aqueous liquid crystals of graphene oxide. ACS Nano 5, 2908–2915 (2011).

Kim, J. et al. Graphene oxide liquid crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 3043–3047 (2011).

Guo, F. et al. Hydration-responsive folding and unfolding in graphene oxide liquid crystal phases. ACS Nano 5, 8019–8025 (2011).

Dan, B. et al. Liquid crystals of aqueous, giant graphene oxide flakes. Soft Matter 7, 11154–11159 (2011).

Xu, Z., Sun, H. Y., Zhao, X. L. & Gao, C. Ultrastrong fibres assembled from giant graphene oxide sheets. Adv. Mater. 25, 188–193 (2013).

Hu, X. Z., Xu, Z. & Gao, C. Multifunctional, supramolecular, continuous artificial nacre fibres. Sci. Rep. 2, 767; 10.1038/srep00767 (2012).

Dong, Z. L. et al. Facile fabrication of light, flexible and multifunctional graphene fibres. Adv. Mater. 24, 1856–1861 (2012).

Cong, H. P., Ren, X. C., Wang, P. & Yu, S. H. Wet-spinning assembly of continuous, neat and macroscopic graphene fibres. Sci. Rep. 2, 613 (2012).

Xu, Z., Zhang, Y., Li, P. G. & Gao, C. Strong, conductive, lightweight, neat graphene aerogel fibres with aligned pores. ACS Nano 6, 7103–7113 (2012).

Hu, X. Z., Xu, Z., Liu, Z. & Gao, C. Liquid crystal self-templating approach to ultrastrong and tough biomimic composites. Sci. Rep. 3, 2374; 10.1038/srep02374 (2013).

Meng, Y. N. et al. All-graphene core-sheath microfibres for all-solid-state, stretchable fibriform supercapacitors and wearable electronic textiles. Adv. Mater. 25, 2326–2331 (2013).

Xiang, C. S. et al. Graphene nanoribbons as an advanced precursor for making carbon fibre. ACS Nano 7, 1628–1637 (2013).

Jalili, R. et al. Scalable one-step wet-spinning of graphene fibers and yarns from liquid crystalline dispersions of graphene oxide: towards multifunctional textiles. Adv. Funct. Mater. 10.1002/adfm.201300765 (2013).

Chen, L. et al. Toward high performance graphene fibres. Nanoscale 5, 5809–5815 (2013).

Liu, Z., Xu, Z., Hu, X. Z. & Gao, C. Lyotropic liquid crystal of polyacrylonitrile-grafted graphene oxide and its assembled continuous strong nacre-mimetic fibres. Macromolecules 46, 6931–6941 (2013).

Xu, Z., Liu, Z., Sun, H. Y. & Gao, C. Highly electrically conductive Ag-doped graphene fibers as stretchable conductors. Adv. Mater. 25, 3249–3253 (2013).

Wang, R. R., Sun, J., Gao, L., Xu, C. H. & Zhang, J. Fibrous nanocomposites of carbon nanotubes and graphene-oxide with synergetic mechanical and actuative performance. Chem. Commun. 47, 8650–8652 (2011).

Zhao, X., Zhang, Q. H., Chen, D. J. & Lu, P. Enhanced mechanical properties of graphene-based poly(vinyl alcohol) composites. Macromolecules 43, 2357–2363 (2010).

Barber, A., Cohen, S. & Wagner, H. Measurement of carbon nanotube-polymer interfacial strength. Appl. Phys. Lett. 82, 4140–4142 (2003).

Park, S. et al. Graphene oxide papers modified by divalent ions-enhancing mechanical properties via chemical cross-linking. ACS Nano 2, 572–578 (2008).

Gao, Y. et al. The effect of inter layer adhesion on the mechanical behaviors of macroscopic graphene oxide papers. ACS Nano 5, 2134–2141 (2011).

Lordi, V. & Yao, N. Molecular mechanics of binding in carbon-nanotube-polymer composites. J. Mater. Res. 15, 2770–2779 (2000).

Sager, R. et al. Effect of carbon nanotubes on the interfacial shear strength of T650 carbon fibre in an epoxy matrix. Compos. Sci. Technol. 69, 898–904 (2009).

Meyers, M., Lin, A. Y., Chen, P. & Muyco, J. Mechanical strength of abalone nacre: role of the soft organic layer. J Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 1, 76–85 (2008).

Tang, Z. Y., Kotov, N., Magonov, S. & Ozturk, B. Nanostructured artificial nacre. Nat. Mater. 2, 413–418 (2003).

Dikin, D. et al. Preparation and characterization of graphene oxide paper. Nature 448, 457–460 (2007).

Qian, D., Dickey, E. C., Andrews, R. & Rantell, T. Load transfer and deformation mechanisms in carbon nanotube-polystyrene composites. Appl. Phys. Lett. 76, 2868–2870 (2000).

Cheng, Q. F., Li, M. Z., Jiang, L. & Tang, Z. Y. Bioinspired layered composites based on flattened double-walled carbon nanotubes. Adv. Mater. 24, 1838–1843 (2012).

Bonderer, L., Studart, A. & Gauckler, L. Bioinspired design and assembly of platelet reinforced polymer films. Science 319, 1069–1073 (2008).

Xu, Z. & Gao, C. In situ polymerization approach to graphene-reinforced nylon-6 composites. Macromolecules 43, 6716–6723 (2010).

Ji, B. H. A study of the interface strength between protein and mineral in biological materials. J Biomech. 41, 259–266 (2008).

Ji, B. H. & Gao, H. J. Mechanical principles of biological nanocomposites. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 40, 77–100 (2010).

Gong, L. et al. Interfacial stress transfer in a graphene monolayer nanocomposite. Adv. Mater. 22, 2694–2697 (2010).

Liu, K. et al. Scratch-resistant, highly conductive and high-strength carbon nanotube-based composite yarns. ACS Nano 4, 5827–5834 (2010).

Pei, S., Zhao, J., Du, J., Ren, W. & Cheng, H. M. Direct reduction of graphene oxide films into highly conductive and flexible graphene films by hydrohalic acids. Carbon 48, 4466–4474 (2010).

Liu, Y. L., Xie, B., Zhang, Z., Zheng, Q. S. & Xu, Z. P. Mechanical properties of graphene papers. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 60, 591–605 (2012).

Holmberg, K., Jönsson, B., Kronberg, B. & Lindman, B. Interaction of polymers with surfaces. Surfactants and polymers in aqueous solution 403–435 (Wiley, Chichester, 2003).

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 51173162 and no. 21325417), Qianjiang Talent Foundation of Zhejiang Province (no. 2010R10021), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (no. 2013XZZX003), Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (no. 20100101110049) and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (no. R4110175). We thank the staffs of BL16B1 Beamline in the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility and the key project (Z12sr0042) for SAXS characterizations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.G. and X.Z. conceived and designed the research, analyzed the experimental data and wrote the paper; X.Z. conducted the experiments; Z.X. and B.Z. contributed the discussion; C.G. supervised and directed the project.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

supporting information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, X., Xu, Z., Zheng, B. et al. Macroscopic assembled, ultrastrong and H2SO4-resistant fibres of polymer-grafted graphene oxide. Sci Rep 3, 3164 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03164

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03164

This article is cited by

-

Microfluidics-enabled orientation and microstructure control of macroscopic graphene fibres

Nature Nanotechnology (2019)

-

Ink-based 3D printing technologies for graphene-based materials: a review

Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials (2019)

-

Nacre-inspired composites with different macroscopic dimensions: strategies for improved mechanical performance and applications

NPG Asia Materials (2018)

-

Strengthening of Ceramic-based Artificial Nacre via Synergistic Interactions of 1D Vanadium Pentoxide and 2D Graphene Oxide Building Blocks

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

A Mini Review on Nanocarbon-Based 1D Macroscopic Fibers: Assembly Strategies and Mechanical Properties

Nano-Micro Letters (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.