Abstract

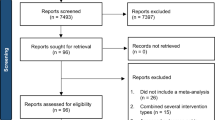

There is little comprehensive research into autistic adulthood, and even less into the services and supports that are most likely to foster flourishing adult autistic lives. This limited research is partly because autism is largely conceived as a condition of childhood, but this focus of research has also resulted from the orthodox scientific approach to autism, which conceptualizes autistic experience almost entirely as a series of biologically derived functional deficits. Approaching autism in this way severely limits what is known about this neurodevelopmental difference, how research is conducted and the services and supports available. In this Review, we adopt an alternative research strategy: we apply Martha Nussbaum’s capabilities approach, which focuses on ten core elements of a thriving human life, to research on autistic adulthood. In doing so, we identify areas where autistic adults thrive and where they often struggle, and highlight issues to which researchers, clinicians and policymakers should respond. The resulting picture is far more complex than conventional accounts of autism imply. It also reveals the importance of engaging autistic adults directly in the research process to make progress towards genuinely knowing autism and supporting flourishing autistic lives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Autism is a lifelong neurodevelopmental difference that influences the way a person interacts and communicates with others and experiences the world around them1. For decades, autism research focused predominantly on autistic children2, in line with the very earliest descriptions of autism3,4 and the tendency for society to depict autism as a disability of childhood5. The result is a substantial lack of understanding about the opportunities and challenges that autistic adults face in building their futures, achieving their goals and living satisfying and fulfilling lives. These issues clearly matter, however, and in the past decade there has been an increase in publications on autistic adulthood, a new journal specifically dedicated to autism in adulthood, a notable increase in funding dedicated to adult-related issues6 and numerous policy interventions designed to assist autistic adults to live good lives7.

Serious obstacles nevertheless continue to prevent researchers, clinicians, educators, policymakers and the broader public from fully grasping the nature of contemporary autistic adulthood. Overcoming these obstacles is vital not only because they constrain understanding but because they also hinder efforts to inform and transform the services and supports that might enhance autistic adults’ lives.

Paramount among these obstacles is the orthodox approach taken in conventional autism research, in which there is an overfocus on ‘deficits’ or ‘impairments’ of autistic adulthood and an overemphasis on specific attributes of individuals as opposed to the broader contexts in which autistic adults live8,9. This conventional research paradigm derives both from long-standing conventions in medicine, which prioritize a putatively objective standard of ‘bodily health’ over a subjective understanding of ‘well-being’10, and from the developmental psychopathology literature, which stresses the importance of ‘patterns of maladaptation’ in shaping the life course of autistic people11. Consequently, individual autistic adults’ behavioural, cognitive and neural functionings are frequently compared with some typical or ‘normal’ level of ability that is held as the ideal ‘state of health’9; interventions and treatments typically aim to remediate these apparent shortcomings to align functioning with the accepted norm. This narrow focus on deficits results in a radically constrained understanding of the experiences that shape autistic lives, limiting the range of supports and services to those that seek to ‘change the individual’ rather than consider how to ‘change the world’. Conventional research efforts are also routinely conducted without meaningful input from autistic people themselves12, meaning that often the wrong questions are posed and findings are misinterpreted. Research of this kind can be said to be ‘lost in translation’13. As such, most research on autism prioritizes researcher-defined normative life goals without discovering how much they matter to a diverse range of autistic people14,15.

In this Review, we — a team of autistic and non-autistic researchers — propose an alternative way of approaching adult autism research. First, we provide some context by briefly discussing the diagnosis and developmental trajectories of autistic adults. Next, we describe Nussbaum’s capabilities approach16,17, which outlines ten central capabilities that enable people, whether autistic or non-autistic, to lead lives that are of value to them on their own terms rather than to meet a predetermined normative standard set by others. We then examine each of the ten capabilities in the context of available autism research. This approach enables us to evaluate the opportunities and challenges facing autistic adults, the forces shaping them and the ways in which services and other interventions might enhance the quality of their lives.

Diagnosis and developmental trajectory

Adult diagnosis of autism first became available in the 1980s (ref.18) and was further encouraged by changes in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) (refs.1,19) several decades later. Many autistic adults initially seek their diagnosis following concerns about social relationships and mental health, sometimes precipitated by a personal crisis or by the diagnosis of their own children. For many, this search for diagnostic clarity is preceded by decades of feeling ‘different’ and of relationship or employment difficulties20,21. Challenges to adult autism diagnosis are discussed in Box 1.

A growing number of adults self-identify as autistic without a formal diagnosis22. This self-identification is controversial in research and clinical communities but is often accepted in the autistic community, in part because, even in high-income countries, autistic adults often remain undiagnosed2,23,24 and, even when formally diagnosed, are only minimally supported2,7,23,24,25. Those diagnosed later in life may have higher self-reported autistic traits and poorer quality of life, especially mental health, than those diagnosed in childhood26.

Following the normative tendencies of the conventional approach to autism research, the vast majority of studies that have examined the developmental trajectories of autistic adults diagnosed in childhood focus on areas thought to be critical for achieving ‘good’ adult outcomes. In longitudinal studies, these outcomes are often defined in terms of a set of standard ‘life achievements’, on which autistic adults typically fare badly14,15. For example, autistic adults with and without intellectual disability followed from childhood are less likely than non-autistic people to hold down a job, live independently or have friends and intimate relationships2,14,15. Other longitudinal studies have examined whether people remain ‘autistic’ (that is, meet instrument and/or clinical thresholds for autism) as they move from childhood into adulthood. These studies show that the diagnostic status of individuals diagnosed in childhood generally endures into adulthood15,27, with the exception of a minority of individuals who no longer display sufficient core autistic features to warrant a clinical diagnosis, which is sometimes described as an ‘optimal outcome’28. Yet despite initial variability, many people show little change in researcher-defined ‘autistic symptoms’ as they move into adulthood29, potentially placing them at greater risk for poor psychosocial outcomes in adulthood30.

More detailed research on the quality of life of autistic adults also largely focuses on the achievement of standard life outcomes, irrespective of whether those outcomes are considered meaningful by autistic adults themselves31,32. Studies that have complemented standard, researcher-defined measures with more subjective, autistic person-led measures (such as quality of life) consistently demonstrate that outcomes are more positive when subjective factors are accounted for14,15. For example, an autistic person who is highly dependent on others for their care — a so-called ‘poor outcome’ according to the standard framework — might nevertheless be happy and subjectively enjoy a very good quality of life. Another autistic person who no longer meets the diagnostic criteria for autism — a so-called ‘good’ outcome — might struggle to find their way in the world and feel different and distant from others. Approaches that focus on researcher-defined measures in this way limit understanding and risk failing to grant autistic people the dignity, agency and respect they deserve.

In considering how to respond to these limitations, it is helpful to establish two clear aims. First, research into autistic adulthood must recognize that people’s life chances (opportunities each individual has to improve their quality of life) are shaped by a range of factors beyond the person, consistent with an ecological perspective33. That is, quality of life is influenced both by biological factors at the heart of the conventional medical model and a broader set of contextual factors as stressed by the social model of disability34. Second, no one, autistic or not, has high quality of life if their life goals are primarily set by others. Thus, quality of life should not be measured by a standard set of outcomes judged to be important by researchers, clinicians or policymakers. Instead, the goals of each individual’s varied human life should be at least partly set by the person themselves35.

A capabilities approach to autistic lives

Martha Nussbaum’s16,17 capabilities approach to quality of life, which has been widely used to analyse social disadvantage in multiple settings, satisfies both of the aims outlined above. First, according to the capabilities approach, a human ‘capability’ is not an intrinsic ability that a person has or does not have solely by virtue of who they are. Instead, ‘capability’ refers to the actual opportunity to be or do something that is facilitated or constrained by features of the person and by the broader contexts in which a person is embedded. The relevant contexts can include close family and household influences; everyday community interactions; educational institutions; economic factors, including the cost of living; services and supports, including accessibility and performance of healthcare institutions; and the broader social and political context, including social attitudes towards autism. Second, flourishing human lives are characterized by a set of these capabilities which enable a person to achieve any number of a range of outcomes, rather than by the attainment of a small number of pre-specified outcomes. These capabilities are considered foundations for a range of doings and beings; they shape what a person can do and, critically, who and how they can be in the world. Capabilities are not a narrow or specific set of achievements, nor are they possessions. Similarly, capabilities cannot be ranked or interpreted by a group of people, such as professionals, or reduced to a single score on a standardized scale. Instead, they refer to the preconditions for a broad range of ways of living.

According to Nussbaum, there are ten central capabilities that most people need if they are to be able to choose and create lives that are meaningful and fulfilling on their own terms16,17 (Table 1). In what follows, we outline how analysing the life chances of autistic adults through this lens can enable a far richer understanding of autistic adults’ lives of all abilities (see Box 2) than the conventional research approach. We do so by highlighting the strengths and challenges of autistic adults in each of the ten central capabilities, and their causes, and consider the potential supports, services and changes in societal attitudes that might help to transform those challenges into strengths. Analysing these capabilities provides a way to examine the lives of autistic adults without narrow normative judgement, while also directing attention to issues that require intervention and support. Readers are advised that some of this material may be distressing and evoke difficult past associations.

Life

The first central capability is “being able to live to the end of a human life of normal length; not dying prematurely, or before one’s life is so reduced as to be not worth living”17. Autistic adults are currently at a substantial disadvantage in this capability. There are persistent patterns of premature mortality in the autistic population36,37. Autistic people are twice as likely to die prematurely as non-autistic people36,37,38, and this risk is greater for autistic women36,38 (but see ref.37) and those with intellectual disability36,37,38. The lives of autistic people are, on average, 16 years shorter than those of non-autistic people36. The risk of death is elevated in autistic people who experience poor physical health or chronic illness (including epilepsy)36,37,38,39. Little is known about the influence of social and economic factors, including access to healthcare, on these mortality rates, but it is widely hypothesized that an important contributor is the extent to which physicians listen to, and learn from, their autistic patients40.

Among the specific causes of premature mortality, there is a higher risk of suicide41,42. Suicide attempts are more frequent and more likely to result in death in autistic people than in non-autistic people36,37,43,44,45, possibly owing to co-occurring psychiatric conditions36. Research focused on understanding why autistic people are at increased risk of self-harm and suicide has identified individual risk markers common to those in the general population, including (younger) age46, low mood and rumination47. More work is needed to understand potentially unique risk markers for increased suicidality in autistic people, including broader interpersonal causes (such as thwarted belonging and perceived burdensomeness) which might mediate associations between autistic traits and suicidality48, and systemic issues (such as clinicians’ lack of knowledge49).

More generally, autistic quality of life in older adulthood (adults aged 50 years and older50) — albeit as assessed using normative measures — is seen as considerably poorer than that in non-autistic older adults51. Social isolation and loneliness are major issues for all older adults, leading to greater risk of dementia and other serious medical conditions52. Both social isolation and loneliness might disproportionately influence older autistic adults, who might be more prone to reclusiveness53, despite many autistic adults describing a longing for interpersonal connection54. For example, in a study in which autistic adults’ experiences of growing older were elicited, one autistic participant said “I think I’m a born loner, quite frankly … Maybe I’m not the kind of person to have a life. Oh, I’d love it, with a person that would understand me”54. There are few longitudinal and participatory studies focusing on autistic older people, including under-represented populations who might have poorer life satisfaction. Thus, little is known about how autistic adults can be supported to live a full and satisfying life into old age in diverse sociocultural contexts55,56.

Bodily health

The second central capability is “being able to have good health, including reproductive health; to be adequately nourished; to have adequate shelter”17. Once again, the evidence suggests that autistic adults are disadvantaged in this regard. Co-occurring physical conditions are common across the autistic lifespan57,58,59 and are more prevalent than in the general population for almost all conditions assessed43,58,59, even when lifestyle factors are considered58. Autistic adults with intellectual disability have distinctive needs59 and might be especially vulnerable to poor physical health60.

Risks for most physical health conditions are further exacerbated for autistic women58,61. Understanding the mechanisms for these differences in health outcomes is critical for reducing these inequalities. Moreover, further clarifying the temporal development of these health problems should inform how interventions are designed to prevent and treat them62. There are at present very few studies on autistic people’s reproductive health. Autistic women report challenging experiences with menstruation, including a cyclical amplification of sensory differences and difficulties with emotional regulation63,64, and autistic women are at greater risk for pregnancy complications65. Autistic women also report significant deterioration in everyday quality of life during menopause66. None of these concerns have yet been investigated in depth. Likewise, there are no studies specifically addressing the reproductive health experiences of autistic men, those with intellectual disability and/or those who are non-speaking; no studies have adopted a less gender-binary approach to reproductive health in autistic adults. This absence of research potentially leaves crucial areas of experience unsupported by clinicians and other policy interventions.

Autistic adults also face barriers to healthcare67,68,69. Despite greater healthcare utilization, medication use and higher healthcare costs than the general population70, autistic adults report more unmet health needs71, lower utilization of preventative care71 and more frequent use of emergency departments71,72 than non-autistic adults. Healthcare settings are often inaccessible to autistic adults, with significant risk of sensory and social overwhelm, miscommunication and lack of autistic-informed care67,73. Autistic people also experience reduced coordination of care compared with non-autistic people, particularly during the transition from paediatric to adult services74. Thus, autistic adults are often left to fend for themselves in navigating the healthcare system75, resulting in negative healthcare experiences and feelings of distrust66,67.

Autistic adults also report poor patient–provider communication (in both directions): autistic adults often face difficulties identifying and articulating their physical health symptoms76 and professionals often do not appreciate the need to adapt their communication style for autistic patients and do not take their autistic patients’ concerns seriously67,68,71. Clinicians’ limited knowledge of68,69 and lack of confidence in75 understanding autistic adults’ specific needs further exacerbate these difficulties. Some tools have been developed to assess barriers to healthcare access experienced by autistic adults from their own perspective71 or from their caregiver’s or healthcare provider’s perspective77. The person-related, provider-related and system-related barriers identified using these tools should facilitate future research that seeks to improve the care and health of autistic people71,78. However, research designed in collaboration with autistic people is needed to assess the most effective ways of improving their healthcare experiences56,67,78.

Many other external factors influence autistic adults’ physical health, such as access to affordable, appropriate housing. Initial studies suggest that autistic adults might be over-represented in homeless communities at rates substantially higher (12–18%79,80) than adult population prevalence estimates (1%81). The range of challenges facing autistic adults might predispose them to homelessness, and reduced social support networks might compound other risk factors, including unemployment, making it difficult for autistic adults to exit homelessness.

Other housing challenges also influence this crucial capability. Compared with other people with disabilities, autistic adults are less likely to live independently, leaving them vulnerable to the inadequacies of institutionalized housing. Formal institutional living and similar settings that purport to be community-based, but are often only nominally so82, have been criticized for displacing people from their families and communities and for providing poor and unresponsive services to residents83,84. Nonetheless, autistic adults continue to be over-represented in more restrictive and segregated settings85.

In sum, the bodily health of autistic adults is severely compromised at present in many regards, owing to failings in clinical provision and in the broader social and economic context within which they must lead their lives.

Bodily integrity

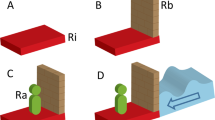

The third capability is that people should be “able to move freely from place to place; to be secure against violent assault; having opportunities for sexual satisfaction and for choice in matters of reproduction”17. This capability is underpinned by a person’s right to make decisions about their body.

There are good reasons to be concerned about autistic disadvantage in accessing this capability. Autistic children are at substantial risk of experiencing multiple forms and repeated occurrences of victimization and abuse86, and this vulnerability persists into adulthood87,88,89,90. In particular, there are elevated rates of sexual victimization in autistic compared with non-autistic adults89,90, especially in autistic women91,92,93 and those who identify as a gender minority92 or as a member of the LGBTQI+ community94. This increased vulnerability might be exacerbated by the fact that autistic people often have reduced access to good quality, effective sexual education95, which can impart vital protective knowledge, as well as by broader structural inequalities (for example, lack of access to healthcare67,68,69).

Autistic adults also experience increased rates of physical assault87,92 and domestic violence, largely perpetrated by people known to them90. Autistic women, particularly those who report multiple traumatic experiences, emphasize deeply distressing betrayals of trust91 and how they often “just couldn’t see it coming”93. Worryingly, these already high victimization rates are likely to be an underestimate: autistic adults are less likely to report experiences of violence to the police87 or even to confide in others87. Autistic adults who experience victimization therefore receive neither the requisite mental health support nor the critical social support that could reduce the likelihood of developing post-traumatic symptoms.

Concerns about physical safety also influence the ability to move freely. Many autistic adults want to be able to access work and go about their daily activities within their communities96, and parents often want this independence for their children too96. Yet both groups worry about safety. Use of public transportation can be challenging for autistic adults owing to lack of accessibility97 and difficulties with wayfinding and traffic judgement98. Furthermore, despite research showing that autistic drivers are more rule-abiding than non-autistic drivers99 and are no more likely to be at fault for a police-reported car crash100, few autistic people take up driving101, partly because of perceived difficulties in spatial awareness, motor coordination, processing speed and executive function96. Consequently, autistic adults can remain reliant on their parents. As one autistic adult expressed in a focus group on understanding autistic adults’ transportation needs and barriers: “If I want to go shopping in the middle of the day I can’t. I have to wait for my mom to come home from work”96.

Finding a balance between autonomy and safety is critical. Autistic children and adults can be more susceptible to wandering102,103, and parents sometimes advocate the use of measures such as tracking devices104. Yet wandering can occur for many reasons102 and is often purposeful104. Researchers and activists warn of the negative impact surveillance technologies can have on people’s independence and urge investment in alternatives such as community supports and safety skills training104,105.

Bodily integrity is inextricably linked to other capabilities. Violations of bodily integrity have adverse effects on other capabilities106, including mental health107, bodily health, interpersonal relationships and sense of agency. Threats to bodily integrity are also likely to influence autistic people’s sense of sexual well-being and their freedom to achieve it. Long-held views of autistic people being uninterested in sexual experiences108 have been firmly quashed by research showing that autistic adults desire sexual relationships to a similar extent as non-autistic adults109,110. Autistic adults in satisfying relationships are more likely to report greater sexual satisfaction, just like non-autistic adults111. They also identify with a wider range of sexual orientations94,109,112 and gender identities113,114,115,116, their sexual ‘debuts’ occur at a later age117 and they have fewer lifetime sexual experiences112 than non-autistic adults. The lack of qualitative studies on the realities of autistic adults’ sexual lives limits understanding, despite the fact that this topic is prioritized by the autistic community118.

Senses, imagination and thought

The fourth capability focuses on being “able to use the senses, to imagine, think, and reason — and to do these things in … a way informed and cultivated by an adequate education … being able to use imagination and thought in connection with experiencing and producing [creative] works … Being able to have pleasurable experiences and to avoid nonbeneficial pain”17. The dominance of the conventional medical model has meant that autism is often associated with deficits in this regard119. There is often a presumption that autistic adults will struggle with higher-order cognition or have low intelligence owing to poor performance on standard intelligence tests120. This stereotype persists even though there is little evidence for it in the everyday experience of the autistic population121. There is an even greater presumption of low intelligence in autistic people who are non-speaking or do not use traditional forms of communication122, who are routinely under-recruited in research123. Similarly, researchers, clinicians and educators have long presumed that creative and imaginative skills and aspirations are limited in autistic people124.

However, the predominant use of standard intelligence tests can lead to an underestimation of autistic people’s intellectual ability120, particularly in non-speaking people125. Autistic people have also been shown to excel at producing novel responses on creative tasks126 and are increasingly recognized for their creative talents127, with major companies investing in autistic people’s ‘out-of-the-box’ thinking128. These strengths have been linked to autistic people’s different way of perceiving the world, including detail-focused processing style129 and enhanced perceptual abilities130, which might be underpinned by heightened sensory perception131.

Nevertheless, autistic people are, in general, poorly served by the educational environments that might further enhance this capability132. They regularly encounter sensory overwhelm within the physical school environment133, struggle with complex social expectations and interactions134, experience bullying and social isolation135, and are stigmatized by a presumption of low competence136. Moreover, limited attention is given to their specific needs, strengths and preferences132,137, including by school staff who lack confidence in supporting autistic students138. Being excluded from139 or not completing140 school can have persisting negative effects on mental health and well-being.

Increasing numbers of autistic adults are enrolling in higher education141, but barriers exist there too. Autistic adults rarely receive relevant supports and accommodations, partly because they are hesitant to disclose their diagnosis or find it difficult to reach out for help141 and partly owing to the absence of formal transition planning142. Consequently, autistic adults are at high risk of dropping out of university143. There is also limited research on the destinations of autistic students who complete higher education144, so it is unclear how to best respond to these challenges.

The senses, imagination and thought capability also emphasizes the importance of being able to take pleasure from sensory experiences. Although research tends to focus on the challenges that autistic sensory differences — such as experiences of sensory overload — bring to people’s everyday lives145, sensory stimuli can also be a source of pleasure146,147. For example, one autistic adult reported enjoying “touching metal a lot … cold smooth metal is, like, just amazing”147. There is also evidence that autistic adults with limited spoken communication in a supported living environment find joy in the everyday, for example in the sound of the washing machine on the last spin or the feel of bubbles while dishwashing146,148.

However, these distinctive sources of pleasure are often pathologized. This is captured by the debate over certain ‘repetitive motor stereotypies’ such as hand-flapping1, which have been reclaimed by autistic adults as ‘stimming’149. These behaviours tend to be perceived as an individual problem with no clear purpose or function that prevent the person from learning skills and interacting with others150. Stimming behaviours are often the target behaviour for interventions that promote ‘calm’ or ‘quiet’ hands151 (cf. ref.152). However, there is very little evidence that stimming behaviours are harmful to autistic people or their peers (the same cannot be said for self-injurious behaviours, which might also be purposeful but are nevertheless harmful to the person). In fact, it now seems likely that stimming behaviours can serve as a source of pleasure or reassurance or a form of self-regulation149.

Emotions

The next capability is defined as “[b]eing able to have attachments to things and people outside ourselves; to love those who love and care for us, to grieve at their absence; in general, to love, to grieve, to experience longing … not having one’s emotional development blighted by fear and anxiety”17. The empirical literature shows that autistic adults have more difficulties recognizing others’ emotions153,154 and identifying and describing their own emotions (alexithymia) than non-autistic people155,156. However, emerging work suggests a far more nuanced picture: autistic adults describe feeling emotions and empathy intensely157 and often experience deeply satisfying emotional lives158.

At their most extreme, the conventionally reported difficulties with emotions were thought to preclude autistic people from the capacity to love or desire meaningful romantic and intimate relationships159. However, research is inconsistent with this claim160. Romantically involved autistic adults report high relationship satisfaction93,161. The strong bonds that autistic adults report with their partners, particularly with those who are also autistic160, extend to their autistic children, with whom they describe an intense connection and love162.

These reports speak strongly against an understanding of autism as a ‘disorder’ of affect. Rather than lack of interest, autistic adults often cite significant challenges with initiating and maintaining romantic relationships154, including difficulties reading and interpreting others’ emotions161, which can impact their capacity to remain romantically involved. The stereotyped assumptions of non-autistic people that autistic people are uninterested in interpersonal relationships might also be an obstacle163. These challenges can intensify feelings of loneliness and are linked to significant negative emotional experiences and poor mental health164. Autistic adults who desire intimate connection but whose needs are unfulfilled might be at particular risk of depression and low self-worth164,165.

This loneliness, depression and poor self-perception can take a substantial toll on mental health and well-being164,166,167. A substantial proportion of autistic adults experience a co-occurring psychiatric condition during their lifetime, with anxiety and mood disorders being the most common168,169. Rates of co-occurring psychiatric conditions are somewhat lower for autistic adults with intellectual disability170, but these rates might be underestimated owing to a lack of detailed understanding in how best to characterize and measure mental health in this context168. The risk of developing mood disorders increases with age168 and autistic adults are at elevated risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder107. Some mental health problems in autistic adults have been attributed to everyday discrimination and internalized stigma171.

The reliance on mental health assessments and diagnostic criteria that were established in non-autistic people168,172,173 and a lack of necessary expertise among health professionals174 might result in an overestimation or underestimation of mental ill health in the autistic population173. Some autistic characteristics might overshadow indicators of mental health conditions (for example, social withdrawal and sleep disturbance are common to both autism and depression), suggesting that co-occurring mental health conditions might go unrecognized173,175. Similarly, mental health diagnoses might overshadow an autism diagnosis, resulting in misdiagnosis175.

Mental health difficulties in autistic adults are likely to be compounded by the inadequacies of formal and informal supports. Autistic adults report a significantly higher number of unmet support needs than the general population25, struggle to obtain appropriate post-diagnostic support176 and face challenges in accessing individually tailored treatment for mental health problems25,176. As one autistic adult put it: “I haven’t requested any, because people like me don’t get support”25. There is a clear need for mental health interventions that are adapted to autistic people’s needs and preferences176.

Practical reason

The next capability, practical reason, is defined as “being able to form a conception of the good and to engage in critical reflection about the planning of one’s own life”17. The three key elements of this capability — choosing what one wants to do, critically reflecting on that choice and making a plan to realize it — are fundamental to making full use of all the other capabilities.

It is sometimes assumed that people with cognitive disability, including some autistic people, are incapable of practical reason, failing even at the initial task of deciding what it is that they value or desire177. Autistic people were traditionally thought to have impaired self-awareness178. A substantial minority of autistic adults have co-occurring intellectual disability (29%179) and some do not use speech to communicate180, which can make it difficult for others to gain insight into their thinking. However, research demonstrates that autistic people have a deep capacity to reflect on many aspects of the self, regardless of their intellect or communication preferences181,182.

The practical reason capability also requires people to be able to reflect critically on their choices, and to change their mind. Here, it seems that autistic people might approach decision-making differently to non-autistic people183,184. Autistic adults make more logically consistent, rational decisions185, are more circumspect in their decision-making, sample more information prior to making a decision186, are less susceptible to social influence187 and are more deliberative in their reasoning188,189.

However, first-hand accounts suggest that such an approach to decision-making can have its disadvantages. For example, autistic people report challenges changing their decisions, especially if the change is unanticipated or requires a shift in routine190. Indeed, autistic people’s tendency to focus intensely on topics or objects of interests (monotropism)191 can make it difficult to ‘move on’ or ‘change gears’192. Interrupting activities after such states of flow and difficulties starting new activities (autistic inertia) can lead to pervasive and often debilitating effects on autistic adults192, including on their ability to design and execute a plan.

Many of the above skills come under the broader umbrella of executive function (higher-order processes that underpin goal-directed activity and enable individuals to respond flexibly to change and plan their actions accordingly)193. Problems with planning, organization and future-oriented thinking are common in autistic adults189, are linked to adaptive difficulties194,195, might be compounded by particular contexts (such as in parenting196 or the workplace197) and are perceived to be real obstacles to achieving desired outcomes198. Interventions and supports that focus on planning and decision-making are scarce, but those that do exist are associated with gains in executive function-related behaviours in real-world settings199.

Affiliation

The next capability is “being able to live with and toward others, to recognise and show concern for other human beings, to engage in various forms of social interaction … and having the social bases of self-respect and nonhumiliation; being able to be treated as a dignified being whose worth is equal to that of others”17. Simply put, that the person is respected as a social being17. Prima facie this might be the capability in which autistic adults might be expected to be at the greatest disadvantage. After all, the term ‘autism’ comes from the Greek autos, meaning both ‘self’ and ‘by itself’, and autistic people are often described as preferring a life of self-isolation163. Dominant characterizations suggest that autistic people lack the motivation200 and/or cognitive building blocks201 for social interaction, which prevents them from establishing and maintaining the types of reciprocal relationships that are fundamental for this capability.

Research has repeatedly shown that autistic children and adolescents have fewer reciprocal friendships202,203, are often on the periphery of social networks202,203 and spend less time with their friends outside school than their non-autistic counterparts204. Autistic adolescents also report a growing awareness of feeling different from others despite wanting to ‘fit in’205,206, and frequently experience social exclusion and bullying135, which might exacerbate their challenges in making and keeping friends. These patterns persist into adulthood207. It is therefore unsurprising that many interventions in adolescence and early adulthood focus on formal social skills training208,209, with the aim of equipping autistic people to manage everyday social relationships on their own terms and, thereby, secure this capability.

However, such interventions fail to appreciate that autistic sociality is shaped by the sociocultural context in which people are embedded208,210,211. Autistic people can and do have fulfilling connections with others, even if negotiating those relationships can be challenging93. They are drawn to those who accept them for who they are154,159,161 and with whom they do not have to mask their autistic ways212,213. These friendships include (but are not restricted to) autistic-to-autistic interactions214,215. As one participant reported in a study on autistic adults’ experiences of loneliness and social relationships: “though many of us have only met each other three to four times, it feels as if we have known each other forever. Because all of a sudden you are in a community with someone where you are on the same wavelength … it is a really strong experience”216. Such autistic-to-autistic interactions promote self-understanding181,214,217, positive self-identity217,218 and well-being219.

Isolation owing to the COVID-19 pandemic has also revealed that autistic people long for social connection in the same way as everyone else, both in terms of close, trusting relationships and fleeting, incidental interactions. As one autistic interviewee said when describing their lockdown experience: “I didn’t realise how important that incidental human contact was to me. It was so incidental that it never really registered on my radar until it was gone”167. Autistic people’s need for human connection and the extent to which social isolation plays a role in autistic people’s mental health distress have been underestimated by conventional accounts.

The double empathy problem220 suggests that there is a misalignment between the minds of autistic and non-autistic people. This misalignment leads to a lack of reciprocity in cross-neurotype interactions and is the source of social communication difficulties between autistic and non-autistic people221,222. Empirical evidence suggests that non-autistic people have difficulties understanding the minds and behaviours of autistic people221,222, and that they are unwilling to interact with autistic people on the basis of initial judgements or interactions221,222,223. Thus, non-autistic people also interact less successfully with autistic people, compared with other non-autistic people224.

These cross-neurotype interaction difficulties can lead to stereotyping of and discrimination against autistic people. Although non-autistic people tend to deny feeling negatively inclined towards autistic people225, autistic people often report experiencing bullying, exclusion and discrimination. Attitudinal research has shown that considerable implicit biases are present, even among non-autistic people who report no explicit biases226, suggesting they may be unaware that they have negative attitudes towards autistic people. These implicit, negative biases are likely to be difficult to shift using short-term educational training programmes227. Such discrimination and stigma constitute a substantial barrier for autistic people seeking to develop social connections. Discrimination and stigma could be countered by widespread public acceptance campaigns (including those developed with autistic people228), and programmes that increase the number of everyday interactions between autistic and non-autistic people229,230.

Other species

The eighth capability requires that humans are “able to live with concern for and in relation to animals, plants and the world of nature”17. Prominent autistic naturalists (such as Temple Grandin) and environmentalists (such as Greta Thunberg) have captured the public’s attention231. Yet there is remarkably little written about autistic people’s connections to nature and non-human animals.

Research with parents of autistic children has revealed that natural elements (such as sand, mud, leaves, twigs and water) can keep children engrossed for extended periods of time232. Some autistic children also prefer interacting with animals over inanimate objects and humans233, and report strong attachments to pets234. Studies have therefore focused on the potential therapeutic benefits of interacting with nature for children, with some purporting to show ‘reduced autistic severity’ or improvements in family functioning following interaction with trained animals235.

Research with autistic adults also reveals benefits of interacting with animals and nature236. Nature and gardening are two of the interests most reported by autistic adults, particularly women, and the pursuit of these interests is positively associated with subjective well-being237. In a study using photovoice methodology, images of natural scenes were frequently included among the photographs shared by autistic adults, demonstrating the importance of nature in contributing to a good autistic life238. Autistic adults’ autobiographies reveal the emotional depth of these connections to nature239, which some autistic people say offer respite from the intensity of an often inhospitable social world.

Play

The capability of play emphasizes the right to be “able to laugh, to play, to enjoy recreational activities”17. This capability is one in which autistic adults might excel. Researchers and clinicians often refer to autistic people’s passions and interests as ‘highly restricted’, ‘perseverative’ or ‘circumscribed’, or as ‘obsessions’ or ‘fixations’, and as differing qualitatively (in content) and quantitatively (in intensity) from the interests of non-autistic people240. Yet autistic testimony attests that these passions are often a great source of joy and enjoyment241, which situates them within the play capability. Intense interests are common in autistic people237,242 and become more diverse over time243. They are not limited to the sciences or computers, as popular stereotypes suggest244, but extend broadly to a range of areas237,242 and might be more idiosyncratic in autistic adults with limited spoken language and/or intellectual disabilities245.

Autistic adults often view their capacity to pursue their passions as an advantage181,237,241,246 that can be affirming and have positive implications for identity and self-concept243. Indeed, one autistic participant, who once “owned about 15,000 CDs,” celebrated the capacity “to be intense in stuff”181. Passions and interests have been likened to experiences of flow237,247 and to monotropism191, which are driven by intrinsic (interest and knowledge) rather than extrinsic (prestige or achievement) motivation237. Finding others who share similar interests can form the basis of long-lasting friendships93. Nevertheless, exceptionally high intensity of engagement may, in some circumstances, negatively impact well-being237.

The generally positive effects of engaging in one’s interests also extend to taking part in recreational activities. Autistic adults report relatively high levels of weekly participation in exercise and hobbies248. However, they participate in conventional social and recreational activities to a lesser extent than the general population249, despite saying these are important to them250. Future research should consider the possible reasons for this disparity and the constraints that autistic adults face when engaging in meaningful and satisfying leisure activities. Inaccessible and inhospitable environments might be barriers for autistic adults251, and the effectiveness of programmes designed to support such participation appear to be limited251,252. Enhancing the play capability is important because engaging in recreational activities might buffer the relationship between perceived stress and quality of life253.

Control over one’s environment

The final capability emphasizes the importance of “being able to participate effectively in political choices that govern one’s life … being able to hold property and having property rights on an equal basis with others; having the right to seek employment on an equal basis with others; having the freedom from unwarranted search and seizure”17.

There is virtually no research on autistic adults’ engagement in mainstream political processes. Individuals with intellectual disability are less likely to vote than the general population254, especially if they live in supported accommodation rather than with family255. They often lack support and accessible information for political engagement255,256 and are even explicitly told they cannot vote due to their intellectual disability256. More research is needed on autistic citizenship to identify precisely how these obstacles can be overcome256.

Extant data suggest that autistic people might be more politically disengaged than non-autistic people. This suggestion stands in contrast to high-profile autistic activists and political commentators, such as Australia’s Grace Tame and Eric Garcia from the United States, and increasing autistic involvement in self-advocacy since the 1990s. The autistic self-advocacy movement grew out of the self-advocacy efforts of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities in the United States and the United Kingdom257, and is perhaps epitomized most by Jim Sinclair’s258 foundational essay (‘Don’t Mourn For Us’) which implored parents not to see their autistic child as a tragedy but, instead, to embrace their differences. Autistic and neurodiversity activists now promote individual self-advocacy, harnessing self-understanding and knowledge to ensure that individuals have greater control over their own lives. Such individual self-advocacy is complemented by collective advocacy, sometimes led by organizations run by and for autistic people (for example, Autistic Self-Advocacy Network), where autistic people collectively campaign on a range of issues259,260 and come together in dedicated autistic spaces and events261. Consequently, self-advocates have begun to shift conceptions of autism from a disorder that needs to be eradicated, prevented or ‘fixed’ to a distinct way of being, which demands acceptance and emphasizes human rights and a positive autistic identity and culture261,262,263,264,265,266,267.

There is much for autistic self-advocates to campaign about. Autistic people’s opportunities are constrained by others’ unjustified assumptions about their capacity268. Autistic adults are at far greater risk of prejudice, stigmatization and discrimination in many facets of their lives, such as education141,269, health40,72, care270, intimate relationships271, community171, justice272 and work273. Moreover, to navigate a world that is not typically set up for them, autistic adults often (consciously or unconsciously) hide or mask aspects of their autistic self274,275 to keep themselves safe or adjust their abilities through ‘compensation’276. Such adaptation can come at serious personal cost, including poor mental and physical health277,278, negative self-perceptions275,278 and autistic burnout279,280.

Work provides a particularly constrained environment. Autistic people face substantial challenges in gaining and sustaining meaningful employment, even relative to other disabled people281,282,283, despite possessing a range of skills that might be prized by employers127,246,282,283. Autistic adults who do obtain employment are often in positions that fail to match up with their abilities (malemployment) or for which they are overqualified (underemployment)284. They can also face challenges maintaining employment285, owing to inhospitable work environments286, negative experiences with (and sometimes bullying by) colleagues281, failure to have their needs and preferences met287, and experiences of discrimination, including following the disclosure of an autism diagnosis288. There is growing interest in paid short-term autism-specific employment programmes or internships, which are designed to reduce barriers to employment for autistic jobseekers, introduce them to workplace life and provide training in job-relevant skills289,290. These initiatives show promising effects on autistic trainees’ occupational self-efficacy289,290 but deserve sustained attention to determine whether they help autistic adults to secure and maintain suitable employment in the longer term. Research is also needed on what constitutes a successful employment outcome according to autistic people themselves, and how it should be measured291.

Summary and future directions

Autistic people deserve to live long, healthy and creative lives of their own design. Just like all people, they need to be equipped with a set of fundamental capabilities to do so. In this Review, we have examined the lives and life chances of autistic adults through Nussbaum’s capabilities16,17 lens. Doing so allows us to escape the narrowly normative focus on specific life outcomes and to consider the broader foundations for a range of possible good autistic lives. When approached in this way, the literature suggests that there are some capabilities in which autistic people have the potential to excel despite conventional stereotypes to the contrary, such as emotions, affiliation, play, connections to other species, practical reason and control over one’s own environment. At the same time, the literature suggests that in these capability areas and others (especially life, bodily health and integrity), autistic adults are often constrained by a range of social, economic and other environmental disadvantages and barriers, which prohibit them from enjoying a good life that they have the right to expect.

This Review suggests two clear directions for future research. First, it will be important for researchers to more clearly identify these externally shaped disadvantages and find ways to alleviate them. That is, once researchers are collectively equipped with a fuller understanding of what currently prevents autistic adults from enjoying a particular capability, they should be able to begin the task of removing those constraints so that further opportunities are provided. Second, it will be equally important to encourage autistic people themselves to reflect further on the capabilities to which they aspire and the obstacles which they believe obstruct them. The capabilities reviewed here are only a starting point and further amendment might be needed to capture the breadth and specificity of autistic experience (see ref.292). Determining what autistic capabilities to add to this list can be resolved only through research that is genuinely participatory (see Box 3); that is, research that places the interests of autistic adults first and takes their own experience and expertise as seriously as any other input.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th ed. (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013).

Howlin, P. Adults with autism: changes in understanding since DSM-III. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 51, 4291–4308 (2021).

Kanner, L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nerv. Child 2, 217–250 (1943).

Asperger, H. in Autism and Asperger Syndrome (ed. Frith, U.) 37–92 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1944).

Stevenson, J., Harp, B. & Gernsbacher, M. Infantilizing autism. Disabil. Stud. Q. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v31i3.1675 (2011).

Cervantes, P. E. et al. Trends over a decade in NIH funding for autism spectrum disorder services research. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 51, 2751–2763 (2021).

Lord, C. et al. The Lancet Commission on the future of care and clinical research in autism. Lancet 399, 10321 (2021).

Leadbitter, K., Buckle, K. L., Ellis, C. & Dekker, M. Autistic self-advocacy and the neurodiversity movement: implications for autism early intervention research and practice. Front. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.635690 (2021).

Pellicano, E. & den Houting, J. Annual research review: shifting from “normal science” to neurodiversity in autism science. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 63, 381–396 (2022).

Brock, D. In The Quality of Life (eds Nussbaum, M. & Sen, A.) 95–132 (Oxford Univ. Press, 1993).

Sroufe, L. A. & Rutter, M. The domain of developmental psychopathology. Child. Dev. 55, 17–29 (1984).

Jivraj, J., Sacrey, L.-A., Newton, A., Nicholas, D. & Zwaigenbaum, L. Assessing the influence of researcher–partner involvement on the process and outcomes of participatory research in autism spectrum disorder and neurodevelopmental disorders: a scoping review. Autism 18, 782–793 (2014).

Pellicano, E., Dinsmore, A. & Charman, T. Views on researcher–community engagement in autism research in the United Kingdom: a mixed-methods study. PLoS ONE 9, e109946 (2014).

Henninger, N. A. & Taylor, J. L. Outcomes in adults with autism spectrum disorders: a historical perspective. Autism 17, 103–116 (2013).

Howlin, P. & Magiati, I. Autism spectrum disorder: outcomes in adulthood. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 30, 69–76 (2017).

Nussbaum, M. Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2000).

Nussbaum, M. Creating Capabilities (Harvard Univ. Press, 2011). This foundational text is a primer on Nussbaum’s capabilities approach, which is an innovative model for assessing human development.

Lai, M. C. & Baron-Cohen, S. Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions. Lancet Psychiatry 2, 1013–1027 (2015).

Lord, C. et al. Autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 6, 5 (2020).

Crane, L. et al. Autism diagnosis in the United Kingdom: perspectives of autistic adults, parents and professionals. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 3761–3772 (2018).

Geurts, H. M. & Jansen, M. D. A retrospective chart study: the pathway to a diagnosis for adults referred for ASD assessment. Autism 16, 299–305 (2011).

Lewis, L. F. Exploring the experience of self-diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in adults. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 30, 574–580 (2016).

Lewis, L. A mixed methods study of barriers to formal diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in adults. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 47, 2410–2424 (2017).

Huang, Y., Arnold, S. R. C., Foley, K.-R. & Trollor, J. N. Diagnosis of autism in adulthood: a scoping review. Autism 24, 1311–1327 (2020).

Camm-Crosbie, L., Bradley, L., Shaw, R., Baron-Cohen, S. & Cassidy, S. People like me don’t get support: autistic adults’ experiences of support and treatment for mental health difficulties, self-injury and suicidality. Autism 23, 1431–1441 (2019).

Atherton, G., Edisbury, E., Piovesan, A. & Cross, L. Autism through the ages: a mixed methods approach to understanding how age and age of diagnosis affect quality of life. J. Autism Dev. Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05235-x (2021).

Woolfenden, S., Sarkozy, V., Ridley, G. & Williams, K. A systematic review of the diagnostic stability of autism spectrum disorder. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 6, 345–354 (2012).

Fein, D. A. et al. Optimal outcome in individuals with a history of autism. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 54, 195–205 (2013).

Simonoff, E. et al. Trajectories in symptoms of autism and cognitive ability in autism from childhood to adult life: findings from a longitudinal epidemiological cohort. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 59, 1342–1352 (2020).

Zimmerman, D., Ownsworth, T., O’Donovan, A., Roberts, J. & Gullo, M. J. High-functioning autism spectrum disorder in adulthood: a systematic review of factors related to psychosocial outcomes. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 43, 2–19 (2018).

McConachie, H. et al. What is important in measuring quality of life? Reflections by autistic adults in four countries. Autism Adulthood 2, 4–12 (2020).

Ne’eman, A. When disability is defined by behavior, outcome measures should not promote ‘passing’. AMA J. Ethics 23, E569–E575 (2021). This opinion piece presents a powerful call to researchers to rethink the measures they use to evaluate autistic people’s outcomes using a neurodiversity lens.

Bronfenbrenner, U. in International Encyclopedia of Education Vol. 3 2nd ed. (eds. Husen, T. & Postlethwaite, N.) 1643–1647 (Elsevier, 1994).

Oliver, M. The Politics of Disablement (MacMillan, 1990).

Raz, J. The Morality of Freedom (Oxford Univ. Press, 1986).

Hirvikoski, T. et al. Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 208, 232–238 (2016).

Hwang, Y. I., Srasuebkul, P., Foley-K-R, Arnold, S. & Trollor, J. N. Mortality and cause of death of Australians on the autism spectrum. Autism Res. 12, 806–815 (2019).

Woolfenden, S., Sarkozy, V., Ridley, G., Coory, M. & Williams, K. A systematic review of two outcomes in autism spectrum disorder: epilepsy and mortality. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 54, 306–312 (2012).

Bishop-Fitzpatrick, L. et al. Using machine learning to identify patterns of lifetime health problems in decedents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 11, 1120–1128 (2018).

Nicolaidis, C. et al. “Respect the way I need to communicate with you”: healthcare experiences of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism 19, 824–831 (2015). This qualitative study, which adopts a community-based participatory approach, presents a thorough analysis of the individual-level, provider-level and system-level factors that impact autistic people’s interactions with the healthcare system.

Cassidy, S. et al. Suicidal ideation and suicide plans or attempts in adults with Asperger’s syndrome attending a specialist diagnostic clinic: a clinical cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 1, 142–147 (2014).

Hedley, D. & Uljarević, M. Systematic review of suicide in autism spectrum disorder: current trends and implications. Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 5, 65–76 (2018).

Hand, B. N., Angell, A. M., Harris, L. & Carpenter, L. A. Prevalence of physical and mental health conditions in Medicare-enrolled, autistic older adults. Autism 24, 755–764 (2020).

Kirby, A. V. et al. A 20-year study of suicide death in a statewide autism population. Autism Res. 12, 658–666 (2019).

Kõlves, K., Fitzgerald, C., Nordentoft, M., Wood, S. J. & Erlangsen, A. Assessment of suicidal behaviors among individuals with autism spectrum disorder in Denmark. JAMA Netw. Open. 4, e2033565 (2021).

Hand, B. N., Benevides, T. W. & Carretta, H. J. Suicidal ideation and self-inflicted injury in medicare enrolled autistic adults with and without co-occurring intellectual disability. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50, 3489–3495 (2019).

South, M. et al. Unrelenting depression and suicidality in women with autistic traits. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50, 3606–3619 (2020).

Pelton, M. K. et al. Understanding suicide risk in autistic adults: comparing the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide in autistic and non-autistic samples. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50, 3620–3637 (2020).

Jager-Hyman, S., Maddox, B. B., Crabbe, S. R. & Mandell, D. S. Mental health clinicians’ screening and intervention practices to reduce suicide risk in autistic adolescents and adults. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50, 3450–3461 (2020).

Roestorf, A. et al. “Older adults with ASD: the consequences of aging”: insights from a series of special interest group meetings held at the International Society for Autism Research 2016–2017. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 63, 3–12 (2019).

van Heijst, B. C. & Geurts, H. M. Quality of life in autism across the lifespan: a meta-analysis. Autism 19, 158–167 (2015).

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System (National Academies Press, 2020).

Hwang, Y., Foley, K. & Trollor, J. Aging well on the autism spectrum: the perspectives of autistic adults and carers. Int. Psychogeriatr. 29, 2033–2046 (2017).

Hickey, A., Crabtree, J. & Stott, J. “Suddenly the first fifty years of my life made sense”: experiences of older people with autism. Autism 22, 357–367 (2018).

Michael, C. Why we need research about autism and ageing. Autism 20, 515–516 (2016).

Warner, G., Parr, J. R. & Cusack, J. Workshop report: establishing priority research areas to improve the physical health and well-being of autistic adults and older people. Autism Adulthood 1, 20–26 (2019). This study, in collaboration with members of the autistic and autism communities, identifies 11 priority areas for research on the physical health and well-being of autistic adults and older people.

Rydzewska, E., Dunn, K. & Cooper, S.-A. Umbrella systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on comorbid physical conditions in people with autism spectrum disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 218, 10–19 (2021).

Weir, E., Allison, C., Warrier, V. & Baron-Cohen, S. Increased prevalence of non-communicable physical health conditions among autistic adults. Autism 25, 681–694 (2020).

Gilmore, D., Harris, L., Longo, A. & Hand, B. N. Health status of medicare-enrolled autistic older adults with and without co-occurring intellectual disability: an analysis of inpatient and institutional outpatient medical claims. Autism 25, 266–274 (2021).

Dunn, K. D., Rydzewska, E., Macintyre, C., Rintoul, J. & Cooper, S.-A. The prevalence and general health status of people with intellectual disabilities and autism co-occurring together — a total population study. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 63, 277–285 (2019).

Kassee, C. et al. Physical health of autistic girls and women: a scoping review. Mol. Autism 11, 84 (2020).

Rubenstein, E. & Bishop-Fitzpatrick, L. A matter of time: the necessity of temporal language in research on health conditions that present with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 12, 20–25 (2019).

Simantov, T. et al. Medical symptoms and conditions in autistic women. Autism 26, 373–388 (2021).

Steward, R., Crane, L., Roy, E., Remington, A. & Pellicano, E. “Life is much more difficult to manage during periods”: autistic experiences of menstruation. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 4287–4292 (2018).

Sundelin, H. E., Stephansson, O., Hultman, C. M. & Ludvigsson, J. F. Pregnancy outcomes in women with autism: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Clin. Epidemiol. 10, 1817–1826 (2018).

Moseley, R. L., Druce, T. & Turner-Cobb, J. M. ‘When my autism broke’: a qualitative study spotlighting autistic voices on menopause. Autism 24, 1423–1437 (2020).

Bradshaw, P., Pellicano, E., van Driel, M. & Urbanowicz, A. How can we support the healthcare needs of autistic adults without intellectual disability? Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 6, 45–56 (2019).

Mason, D. et al. A systematic review of what barriers and facilitators prevent and enable physical healthcare services access for autistic adults. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49, 3387–3400 (2019).

Walsh, C., Lydon, S., O’Dowd, E. & O’Connor, P. Barriers to healthcare for persons with autism: a systematic review of the literature and development of a taxonomy. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 23, 413–430 (2020).

Zerbo, O. et al. Health care service utilization and cost among adults with autism spectrum disorders in a US integrated health care system. Autism Adulthood 1, 27–36 (2018).

Nicolaidis, C. et al. Comparison of healthcare experiences in autistic and non-autistic adults: a cross-sectional online survey facilitated by an academic–community partnership. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 28, 761–769 (2013).

Tregnago, M. K. & Cheak-Zamora, N. C. Systematic review of disparities in health care for individuals with autism spectrum disorders in the United States. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 6, 1023–1031 (2012).

Micai, M. et al. Autistic adult health and professional perceptions of it: evidence from the ASDEU project. Front. Psychiatry 12, 614102 (2021).

Anderson, K. A., Sosnowy, C., Kuo, A. A. & Shattuck, P. T. Transition of individuals with autism to adulthood: a review of qualitative studies. Pediatrics 141, S318–S327 (2018).

Unigwe, S. et al. GPs’ perceived self-efficacy in the recognition and management of their autistic patients: an observational study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 67, e445–e452 (2017).

Fiene, L. & Brownlow, C. Investigating interoception and body awareness in adults with and without autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 8, 709–716 (2015).

Walsh, C. et al. Development and preliminary evaluation of a novel physician-report tool for assessing barriers to providing care to autistic patients. BMC Health Serv. Res. 21, 873 (2021).

Walsh, C., O’Connor, P., Walsh, E. & Lydon, S. A systematic review of interventions to improve healthcare experiences and access in autism. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-021-00279-2 (2021).

Churchard, A., Ryder, M., Greenhill, A. & Mandy, W. The prevalence of autistic traits in a homeless population. Autism 23, 665–676 (2019).

Evans, R. The Life We Choose: Shaping Autism Services in Wales (National Autistic Society, 2011).

Brugha, T. et al. Epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders in adults in the community in England. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 68, 459–465 (2011).

Autistic Self Advocacy Network. ASAN Toolkit on Improving Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) https://autisticadvocacy.org/policy/toolkits/hcbs/ (2011).

Mandell, D. A house is not a home: the great residential divide in autism care. Autism 21, 810–811 (2017).

Paode, P. Housing for Adults with Autism and/or Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: Shortcomings of Federal Programs (Daniel Jordan Fiddle Foundation, 2020).

Allely, C. S. A systematic PRISMA review of individuals with autism spectrum disorder in secure psychiatric care: prevalence, treatment, risk assessment and other clinical considerations. J. Crim. Psychol. 8, 58–79 (2018).

Mandell, D. S., Walrath, C. M., Manteuffel, B., Sgro, G. & Pinto-Martin, J. A. The prevalence and correlates of abuse among children with autism served in comprehensive community-based mental health settings. Child Abuse Negl. 29, 1359–1372 (2005).

Gibbs, V. et al. Experiences of physical and sexual violence as reported by autistic adults without intellectual disability: rate, gender patterns and clinical correlates. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 89, 101866 (2021).

Weiss, J. A. & Fardella, M. A. Victimisation and perpetration experiences of adults with autism. Front. Psychiatry 9, 203 (2018).

Brown-Lavoie, S. M., Viecili, M. A. & Weiss, J. A. Sexual knowledge and victimization in adults with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 44, 2185–2196 (2014).

Griffiths, S. et al. The vulnerability experiences quotient (VEQ): a study of vulnerability, mental health and life satisfaction in autistic adults. Autism Res. 12, 1516–1528 (2019).

Bargiela, S., Steward, R. & Mandy, W. The experiences of late-diagnosed women with autism spectrum conditions: an investigation of the female autism phenotype. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 46, 328–3294 (2016).

Reuben, K. E., Stanzione, C. M. & Singleton, J. L. Interpersonal trauma and posttraumatic stress in autistic adults. Autism Adulthood 3, 247–256 (2021).

Sedgewick, F., Crane, L., Hill, V. & Pellicano, E. Friends and lovers: the relationships of autistic women in comparison to neurotypical women. Autism Adulthood 1, 112–123 (2019).

Pecora, L. A., Hancock, G. I., Mesibov, G. B. & Stokes, M. A. Characterising the sexuality and sexual experiences of autistic females. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49, 4834–4846 (2019).

Solomon, D., Panatalone, D. W. & Faja, S. Autism and adult sex education: a literature review using the information–motivation–behavioral skills framework. Sex. Disabil. 37, 339–351 (2019).

Lubin, A. & Feeley, C. Transportation issues of adults on the autism spectrum: findings from focus group discussions. Transp. Res. Rec. 2542, 1–8 (2016).

Kersten, M., Coxon, K., Lee, H. & Wilson, N. J. Independent community mobility and driving experiences of adults on the autism spectrum: a scoping review. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 74, 7405205140 (2020).

Deka, D., Feeley, C. & Lubin, A. Travel patterns, needs, and barriers of adults with autism spectrum disorder: report from a survey. Transp. Res. Rec. 2542, 9–16 (2016).

Chee, D. Y.-T. et al. Viewpoints on driving of individuals with and without autism spectrum disorder. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 18, 26–36 (2015).

Curry, A. E. et al. Comparison of motor vehicle crashes, traffic violations, and license suspensions between autistic and non-autistic adolescent and young adult drivers. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 60, 913–923 (2021).

Curry, A. E., Yerys, B. E., Huang, P. & Metzger, K. B. Longitudinal study of driver licensing rates among adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 22, 479–488 (2018).

Anderson, C. J. et al. Occurrence and family impact of elopement in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 130, 870–877 (2012).

Solomon, O. & Lawlor, M. C. “And I look down and he is gone”: narrating autism, elopement and wandering in Los Angeles. Soc. Sci. Med. 94, 106–114 (2013). This anthropological research analyses narratives from African American mothers of autistic children about wandering, highlighting the cultural context of these phenomena in a group under-represented in research.

Ne’eman, A. Safety versus autonomy: advocates for autistic children split over tracking devices. Vox https://www.vox.com/the-big-idea/2016/12/17/13993398/safety-autonomy-avonte-tracking-autism-wandering-schumer (2016).

Baggs, A. Wandering. Ballastexistenz https://ballastexistenz.wordpress.com/2005/08/01/wandering/ (2005).

Wolff, J. & de-Shalit, A. Disadvantage (Oxford Univ. Press, 2007).

Rumball, F., Happé, F. & Grey, N. Experience of trauma and PTSD symptoms in autistic adults: risk of PTSD development following DSM-5 and non-DSM-5 traumatic life events. Autism Res. 13, 2122–2132 (2020).

Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, H. Becoming an ‘autistic couple’: narratives of sexuality and couplehood within the Swedish Autistic self-advocacy movement. Sex. Disabil. 32, 351–363 (2014).

Dewinter, J., De Graaf, H. & Begeer, S. Sexual orientation, gender identity and romantic relationships in adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 47, 2927–2934 (2017).

Gilmour, L., Smith, V. & Schalomon, M. in Comprehensive Guide to Autism (eds Patel, V. B., Preedy, V. R. & Martin, C. R.) 569–584 (Springer, 2014).

Byers, E. & Nichols, S. Sexual satisfaction of high-functioning adults with autism spectrum disorder. Sex. Disabil. 32, 365–382 (2014).

Bush, H. H. Dimensions of sexuality among young women, with and without autism, with predominantly sexual minority identities. Sex. Disabil. 37, 275–292 (2019).

George, R. & Stokes, M. A. Gender identity and sexual orientation in autism spectrum disorder. Autism 22, 970–982 (2018).

Strang, J. F. et al. Increased gender variance in autism spectrum disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch. Sex. Behav. 43, 1525–1533 (2014).

Van Der Miesen, A. I. R., Hurley, H. & De Vries, A. L. C. Gender dysphoria and autism spectrum disorder: a narrative review. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 28, 70–80 (2016).

Warrier, V. et al. Elevated rates of autism, other neurodevelopmental and psychiatric diagnoses, and autistic traits in transgender and gender-diverse individuals. Nat. Comm. 11, 3959 (2020).

Barnett, J. P. & Maticka-Tyndale, E. Qualitative exploration of sexual experiences among adults on the autism spectrum: implications for sex education. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 47, 171–179 (2015).

Dewinter, J., van der Miesen, A. I. R. & Graham Holmes, L. INSAR Special Interest Group Report: stakeholder perspectives on priorities for future research on autism, sexuality and intimate relationships. Autism Res. 13, 1248–1257 (2020).

Dinishak, J. The deficit view and its critics. Disabil. Stud. Q https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v36i4.5236 (2016).

Dawson, M., Soulieres, I., Gernsbacher, M. A. & Mottron, L. The level and nature of autistic intelligence. Psychol. Sci. 18, 657–662 (2007). This pioneering study refutes the long-standing view that the majority of autistic people are intellectually impaired.

Goldberg Edelson, M. Are the majority of children with autism mentally retarded? A systematic evaluation of the data. Focus. Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 21, 66–83 (2006).

Alvares, G. A. et al. The misnomer of ‘high functioning autism’: intelligence is an imprecise predictor of functional abilities at diagnosis. Autism 24, 221–232 (2020).

Russell, G. et al. Selection bias on intellectual ability in autism research: a cross-sectional review and metaanalysis. Mol. Autism 10, 9 (2019).

Craig, J. & Baron-Cohen, S. Creativity and imagination in autism and Asperger syndrome. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 29, 319–326 (1999).

Courchesne, V., Meilleur, A.-A. S., Poulin-Lord, M.-P., Dawson, M. & Soulières, I. Autistic children at risk of being underestimated: school-based pilot study of a strength-informed assessment. Mol. Autism 6, 12 (2015).

Kasirer, A. & Mashal, N. Verbal creativity in autism: comprehension and generation of metaphoric language in high-functioning autism spectrum disorder and typical development. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8, 615 (2014).

de Schipper, E. et al. Functioning and disability in autism spectrum disorder: a worldwide survey of experts. Autism Res. 9, 959–969 (2016).

Austin, R. D. & Pisano, G. P. Neurodiversity as a competitive advantage. Harv. Bus. Rev. 95, 96–103 (2017).

Happé, F. & Vital, P. What aspects of autism predispose to talent? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 364, 1369–1375 (2009).

Mottron, L., Dawson, M., Soulières, I., Hubert, B. & Burack, J. Enhanced perceptual functioning in autism: an update, and eight principles of autistic perception. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 36, 27–43 (2006).

Proff, I., Williams, G. L., Quadt, L. & Garfinkel, S. N. Sensory processing in autism across exteroceptive and interoceptive domains. Psychol. Neurosci. 15, 105–130 (2021).

Goodall, C. ‘I felt closed in and like I couldn’t breathe’: a qualitative study exploring the mainstream educational experiences of autistic young people. Autism Dev. Lang. Impair. 3, 1–16 (2018).

Jones, E. K., Hanley, M. & Riby, D. M. Distraction, distress and diversity: exploring the impact of sensory processing differences on learning and school life for pupils with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 72, 101515 (2020).

Williams, E., Gleeson, K. & Jones, B. E. How pupils on the autism spectrum make sense of themselves in the context of their experiences in a mainstream school setting: a qualitative metasynthesis. Autism 23, 8–28 (2019).

Maïano, C., Normand, C. L., Salvas, M. C., Moullec, G. & Aime, A. Prevalence of school bullying among youth with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Autism Res. 9, 601–615 (2016).

Biklen, D. Presuming competence, belonging, and the promise of inclusion: the US experience. Prospects 49, 233–247 (2020).

Makin, C., Hill, V. & Pellicano, E. The primary-to-secondary school transition for children on the autism spectrum: a multi-informant mixed-methods study. Autism Dev. Lang. Impair. 2, 1–18 (2017).

Robertson, K., Chamberlain, B. & Kasari, C. General education teachers’ relationships with included students with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 33, 123–130 (2003).

Brede, J., Remington, A., Kenny, L., Warren, K. & Pellicano, E. Excluded from school: examining the educational experiences of students on the autism spectrum. Autism Dev. Lang. Impair. 2, 1–20 (2017).

Ringbom, I. et al. Psychiatric disorders diagnosed in adolescence and subsequent long-term exclusion from education, employment or training: longitudinal national birth cohort study. Br. J. Psychiatry 220, 148–153 (2021).

Nuske, A., Rillotta, F., Bellon, M. & Richdale, A. Transition to higher education for students with autism: a systematic literature review. J. Divers. High. Educ. 12, 280–295 (2019).