Abstract

In spring, Eurasia has experienced significant warming, accompanied by frequent extreme heat events. Whether the Arctic sea ice has contributed to the variation of spring Eurasian extreme heat events is still unclear. Here, through conducting statistical analyses of observed and reanalysis data, we demonstrate that the winter sea ice anomalies over the Barents-Kara Seas dominate the leading mode of interannual variation of spring extreme heat events over mid-to-high latitude Eurasia in the recent two decades. With faster decline rate and larger variability, the winter sea ice anomalies over the Barents-Kara Seas significantly enhance the troposphere-stratosphere interactions and further exert influence on the spring atmospheric circulations that favor the formation of Eurasian extreme heat events. Cross-validated hindcasts of the dipole mode index of spring extreme heat events using winter sea ice anomalies over the Barents-Kara Seas yield a correlation skill of 0.71 over 2001–2018, suggesting that nearly 50% of its variance could be predicted one season in advance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the global warming as well as Arctic amplification, one of the most pronounced changes that occurred in the Arctic is the rapid decline in sea ice extent1,2, thickness3,4, and ice season duration5,6. Satellite data since 1979 show that the negative trends of Arctic sea ice extent occur in all months, with the largest decreased trend in September. Since the 21st century, the reduction of winter sea ice is significant, with the strongest reduction in the Barents-Kara Seas (BK)7,8. The unprecedented decline in Arctic sea ice is speculated to be responsible for more frequent extreme weather events in mid-latitudes in recent decades. For example, a number of previous studies indicated that winter atmospheric responses to the autumn/winter Arctic sea ice reduction favor extreme cold winters in mid-latitude Eurasia and North America9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. Along with the dramatic reduction in sea ice, the ice-free surface provides sufficient moisture for snowy weather over Eurasia22,23,24. In addition, atmospheric responses to Arctic sea ice loss could also increase air pollution over eastern China and the Tibetan Plateau25,26. In the linkage between Arctic amplification and sea ice loss with mid-latitude weather, three potential dynamical pathways are revealed: changes in storm tracks mainly in the North Atlantic sector, changes in the characteristics of the jet stream, and regional changes in the tropospheric circulation that trigger anomalous planetary wave configurations27.

Different from severe cold and snowy mid-latitude winters in recent years, Eurasia has experienced a widespread and rapid warming in spring28,29,30. More frequent spring extreme heat events (EHE) could have devastating influence on the ecosystems and human health31,32,33. For example, northern Siberia experienced exceptionally high temperatures in spring 2020, with the hottest May on record. The temperature for March–May mean is 4.8 °C higher than the 1981‒2010 climatological average, exerting impact on the local natural environment34. However, despite the studied influence of atmospheric blocking on European spring temperature extremes35, currently understanding of the mechanisms for the spring EHE variation over Eurasia remains limited. Motivated by the aforementioned researches on the influence of the Arctic sea ice, this study investigates the relationship between the Arctic sea ice and spring EHE variations over Eurasia. Our analysis presents empirical evidence that, along with an accelerated decline of winter BK sea ice since the late 1990s36, there is an enhanced impact of winter BK sea ice on the dominant mode of spring EHE interannual variation over mid-to-high latitude Eurasia in the most recent two decades. We further suggest that winter BK sea ice could be a potential predictor for the interannual variation of spring EHE over Eurasia.

Results

Enhanced linkage between winter BK sea ice and following spring Eurasian EHE in the recent two decades

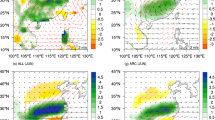

The singular value decomposition (SVD) method is used to reveal the dominant interannual coupled mode between spring Eurasian EHE and preceding winter BK sea ice concentration (SIC) during the period of 2001–2018 (Fig. 1a–c). The first SVD mode (SVD1) explains ~59.8% of the total covariance. The spring EHE pattern in SVD1 is characterized by a north-south dipole structure, with significant negative anomalies over northern Europe and western Siberia and positive anomalies over mid-latitudes and eastern Siberia (Fig. 1a). Correspondingly, the preceding winter sea ice pattern shows significant and negative anomalies in the BK region (Fig. 1b). The correlation coefficient between the two SVD1 time series reaches 0.83, statistically significant at the 99.9% confidence level based on the Student’s t test (Fig. 1c).

a Spring (MAM(0)) EHE pattern (units: %) in SVD1, and b preceding winter (DJF(−1)) SIC pattern in SVD1, which are obtained by regressing the SIC and EHE anomalies onto the normalized two SVD1 time series during 2001–2018, respectively. The two red boxes (P1: 35°−57°N, 20°−120°E, and P2: 50°−70°N, 125°−165°E) and blue box (N: 60°−76°N, 20°−120°E) in (a) are the domains used to define the spring EHE dipole mode index. The dashed blue box (76°−83°N, 11°−75°E and 68°−76°N, 50°−75°E) in (b) is the BK region used to define the winter BK sea ice index. Dotted areas in (a) and (b) denote anomalies significant at the 90% confidence level. c Normalized two SVD1 time series. The explained covariance by the SVD1 and the correlation (R) between the two SVD1 time series are shown in the top of (c). d Cross wavelet transform of the indices of winter BK sea ice and spring EHE dipole mode. In (d), the thick black contour denotes the 90% significance level and light shading indicates the cone of influence where edge effects might distort the picture.

To further understand the relationship in variations between winter BK sea ice and spring Eurasian EHE, the spatial-temporal characteristics of winter BK SIC and spring Eurasian EHE are investigated. According to the EHE dipole mode in Fig. 1a, the two EHE time series are defined as the EHE anomalies averaged over the two red boxes and one blue box. The two normalized EHE time series show an increasing trend during 1980–2021 (Supplementary Fig. 1a), indicating that there is a greater frequency of spring EHE over mid-to-high latitude Eurasia in the recent two decades. The normalized difference between the two EHE time series is referred to as the spring EHE dipole mode index. The moving t-tests with different windows consistently show a significant decadal change of the EHE dipole mode index around 2000 (Supplementary Fig. 1b). The moving t-test result indicates that there could be a decadal change in the leading mode of spring EHE interannual variability over mid-to-high latitude Eurasia around 2000. To confirm, we further calculate the dominant empirical orthogonal function (EOF) modes of spring EHE interannual variability over two subperiods of pre-2000 and post-2000. Interestingly, the leading EHE mode changed from a mono‐sign pre-2000 to a north-south dipole post-2000 (Supplementary Fig. 1c–d). Such a result indicates that the dipole mode becomes the dominant mode of spring EHE interannual variation over mid-to-high latitude Eurasia after 2000.

In winter, the BK sea ice experienced the strongest reduction over the Arctic during the 21st century. Compared to pre-2000, the mean state of BK SIC had a significant decrease in post-2000; in addition, the interannual variability of SIC had also a significant increase (Supplementary Fig. 2a–b). The EOF analysis further indicates that the variability of the BK SIC is the dominant mode of winter Arctic SIC after 2000 (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Such a sea ice leading mode in EOF (EOF1) exhibits a high similarity to that in SVD1 (Fig. 1b). According to the significant SIC anomalies in EOF1 and SVD1 modes, the winter BK sea ice index is defined as the normalized regional-mean SIC anomalies over the BK region (Supplementary Fig. 2d). The index analysis shows that winter BK SIC has strong interdecadal and interannual variations. The decline trend of winter BK SIC accelerated from −0.16 per 10-year in pre-2000 to −0.71 per 10-year post-2000, indicating a fourfold increase in the decreasing trend of winter BK SIC in the most recent two decades compared to previously. In addition, the interannual variability of winter BK SIC also increased from 0.47 pre-2000 to 0.99 post-2000.

Figure 1d shows the cross wavelet transform of the indices of winter BK sea ice and spring EHE dipole mode over the period of 1980–2021. The figure suggests that the two indices have significant common power in the period band of 4–8 year after 2000 and the winter BK sea ice leads the spring EHE changes, suggesting that the winter BK sea ice could be a precursor to spring Eurasian EHE interannual variations since 2000. On the interannual timescale, the correlation coefficient between spring EHE dipole mode index and preceding winter BK sea ice index during post-2000 (2001–2018) is −0.77, significant at the 99.9% confidence level.

Physical process for the linkage between winter BK sea ice and following spring Eurasian EHE

The analysis in the last section indicates that the winter BK SIC anomalies have significant seasonal lagged linkage with the dominant mode of the following spring EHE over mid-to-high latitude Eurasia in the recent two decades. The next question is: what physical processes are responsible for such a seasonal lagged linkage since 2000? In the remainder of the paper, we provide supporting analysis for this mechanism.

Sea ice decline increases the open water and thus greatly enhances turbulent heat fluxes from the ocean to the atmosphere, especially in winter when the sea-air temperature difference is large. Supplementary Fig. 3 shows the regressed surface turbulent heat fluxes (sensible plus latent heat fluxes) anomalies on the negative winter BK sea ice index in two subperiods. Along with the accelerated reduction and increased interannual variability of winter BK SIC in the recent two decades, the ocean releases more turbulent heat fluxes to the atmosphere over the BK region (Supplementary Fig. 3b). The area-mean upward turbulent heat flux anomalies associated with reduced winter BK sea ice are increased by 38% post-2000 compared with pre-2000.

More upward turbulent heat flux due to the larger decrease in sea ice indicates an enhanced sea ice influence on the atmosphere37. Corresponding to the rapid reduction of winter BK sea ice after 2000, the winter geopotential height exhibits positive anomalies over the Arctic and negative anomalies over northern Asia (Fig. 2a), which is relevant to the warm Arctic–cold Eurasian pattern38. To further examine the reduced winter BK sea ice-related circulation structure and wave activity flux (WAF) in three-dimensions, a vertical cross-section along the line connecting the positive and negative geopotential height centers (marked A and B in Fig. 2a) is presented. As shown in Fig. 3a, the geopotential height anomalies reflect an equivalent barotropic structure, and strong WAF propagates upward in the winter BK sea ice-related positive geopotential height region.

Vertical component of 200-hPa WAF (10−3 m2 s−2, shading) and 100-hPa geopotential height (m, contour) anomalies in a DJF(−1), b February–March (FM(0)), c March-April (MA(0)), and d April–May (AM(0)) regressed onto the negative winter BK sea ice index. The green line in (a) is from grid A (75°N, 50°E) to grid B (58°N, 163°E). The green boxes in (c) are the regions of Greenland (GL, 50°−70°N, 35°−90°W) and eastern Siberia (ES, 48°−68°N, 107°−177°E). Contour interval is 8 m. Blue and red contours indicate the negative and positive geopotential height anomalies. Hatched areas denote geopotential height anomalies significant at the 90% confidence level.

a Cross-section of geopotential heights (m, contour) and the zonal and vertical components of the WAF anomalies (m2 s−2, vector) regressed onto the negative winter BK sea ice index along the green line in Fig. 2a and extending northwestward and southeastward to grids (0°, 84°N and 180°, 55°N). The vertical component of the WAF in (a) is multiplied by 100. Gray shading in (a) denote geopotential height anomalies significant at the 90% confidence level. b Winter WN1 component of geopotential heights at 500-hPa (m, shading) regressed onto the negative winter BK sea ice index and the climatological WN1 (m, contour). Contour intervals are 10 m in (a) and 20 m in (b).

In the seasonal lagged impact of Arctic sea ice, previous studies suggested that stratosphere–troposphere interaction could be an important physical mechanism linking autumn BK sea ice anomalies and following winter atmospheric circulation anomalies39,40,41,42. Thus, we examine the contributions of zonal wavenumber 1 (WN1) and wavenumber 2 (WN2) components of atmospheric circulations, which are primary upward propagating waves that contribute to the weakening of polar vortex43. In the BK sea ice-related planetary-scale waves, the amplitude of WN2 anomalies is much smaller than WN1; therefore, the WN2 could play a limited role in the winter BK sea ice-related stratosphere–troposphere interaction, and consequently we focus on WN1 anomalies. As shown in Fig. 3b, WN1 anomalies after 2000 are in phase with its climatological mean. The linear constructive interference of WN1 greatly enhances the upward propagation of wave energy, so that notable upward WAF can be seen over most of the high-latitude region in winter after 2000 (Fig. 2a). The above analysis suggests that the reduction of BK sea ice after 2000 can enhance the upward transport of wave energy in winter by causing the in-phase WN1 disturbance.

The Eliassen–Palm (EP) flux in Fig. 4 further illustrates the impact of BK sea ice loss on wave propagation. The reduced BK sea ice is related to enhanced upward propagation of EP flux at 60°N in winter (Fig. 4a). The convergences of anomalous EP flux in the stratosphere decelerate the westerly winds44. In FM(0), weak upward propagation of anomalous EP flux still exists in the uppermost stratosphere, while downward propagation of anomalous EP flux starts in the lower troposphere (Fig. 4b). The enhanced upward propagating EP flux associated with the BK sea ice loss during winter to early spring results in a weakened stratospheric polar vortex (Fig. 2b). The lower stratospheric atmospheric anomalies can last for about two months, and propagate downward to the lower troposphere45,46. Therefore, during spring, there are anomalous downward propagating EP flux centered at 60 °N (Fig. 4c, d). In this process, the polar vortex gradually recovers and the positive geopotential height center extends towards Greenland, the Caspian Sea region, and eastern Siberia in MA(0) (Fig. 2c). In AM(0), the Arctic is covered by negative geopotential height anomalies, indicating the recovery of the polar vortex (Fig. 2d).

Zonal mean EP flux (108 m2 s−2, vector), EP flux divergence (m s−1 day−1, shading), and zonally mean zonal wind (m s−1, contour) anomalies in a DJF(−1), b FM(0), c MA(0), and d AM(0) regressed onto the negative winter BK sea ice index. Vectors are scaled by\(\sqrt{1000/P}\), and vertical EP flux is multiplied by 125 for display. Contour interval is 1 m s−1. Blue and red contours indicate the negative and positive zonal wind anomalies. Dotted areas denote EP flux divergence anomalies significant at the 90% confidence level.

Supplementary Fig. 4 presents the time-pressure cross-sections of geopotential height anomalies averaged over Greenland and eastern Siberia. Corresponding well to downward EP flux propagation at 60°N during FM(0) to MA(0) (Fig. 4b–d), the stratospheric positive geopotential height anomalies over Greenland and eastern Siberia gradually propagate downward and reach the troposphere in spring (Supplementary Fig. 4). Therefore, in spring, the reduced BK sea ice-related atmospheric circulations exhibit significant positive centers and Rossby wave source (RWS) over Greenland and eastern Siberia (Fig. 5). In addition, the anomalous geopotential height and RWS over Greenland in spring excite a horizontal Rossby wave train propagating across mid-to-high latitude Eurasia to the North Pacific (Fig. 5). This zonal wave train can result in negative geopotential height anomalies over western to northern Europe and western Siberia and positive geopotential height anomalies over the Caspian Sea region and eastern Siberia.

Spring RWS (10−11 s−2, shading) and geopotential height anomalies (m, contour) at 300-hPa regressed onto the negative winter BK sea ice index and the related horizontal WAF (m2 s−2, vector). WAF values lower than 0.05 m2 s−2 are not plotted. Contour interval is 5 m. Blue and pink contours indicate the negative and positive geopotential height anomalies. The RWS anomalies significant at the 90% confidence level are plotted. Hatched areas denote geopotential height anomalies significant at the 90% confidence level.

The BK sea ice-related spring atmospheric pattern shows a quasi-barotropic structure in the troposphere (Supplementary Fig. 5a–c), and it is highly similar to that associated with spring EHE dipole mode (Supplementary Fig. 5d–f). Such a similarity further supports the close connection between preceding winter BK sea ice and spring Eurasian EHE variability. The BK sea ice-related atmospheric pattern can affect the total cloud cover and surface heat fluxes over Eurasia (Supplementary Fig. 6a, c, e). Specifically, positive geopotential height anomalies over mid-latitudes and eastern Siberia could reduce total cloud cover there, allowing more shortwave radiation to reach and heat the surface of the region (Supplementary Fig. 6c). In turn, the warm land surface heats the surface air mainly by releasing long-wave radiation (Supplementary Fig. 6e), facilitating more EHE over the mid-latitudes and eastern Siberia (Fig. 1a). In addition, 850-hPa southerly winds over mid-latitudes and eastern Siberia induce a warm temperature advection, also contributing to more EHE over the region (Supplementary Fig. 6g). In contrast, the BK sea ice-related spring atmospheric pattern leads to more total cloud cover and cold temperature advection over northern Europe and western Siberia, consequently, providing supportive conditions for less EHE over the region. The aforementioned spring heat flux and temperature advection anomalies associated with the BK sea ice are consistent with that associated with the EHE dipole mode (Supplementary Fig. 6b, d, f, h), therefore providing a favorable climate background condition for the variation of the EHE dipole pattern over mid-to-high latitude Eurasia.

Over large parts of the high-latitude continents, warm temperature extremes often occur simultaneously with atmospheric blocking at the same location47. Therefore, the winter BK sea ice-related frequency of spring blocking is further calculated. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 7, along with the BK sea ice-related atmospheric pattern, there are significant increases in the frequency of blocking over eastern Siberia but a decrease over northern Europe and western Siberian. Such changes in the frequency of blocking also contribute to the dipole distribution of the EHE over high-latitude Eurasia.

In this study, the spring mean atmospheric circulations associated with the BK sea ice are diagnosed, which could provide a favorable background for the occurrence of Eurasian EHE. The occurrence of the EHE is directly associated with synoptic and intraseasonal atmospheric processes, therefore future study on the BK sea ice-related atmospheric circulations from the synoptic and intraseasonal timescales is necessary to further understand its connection with the spring Eurasian EHE occurrence.

Cross-validated hindcasts of the interannual variation of spring EHE dipole mode using winter BK SIC anomalies

The analysis in the last section shows there are interdecadal changes in the interannual variation of spring Eurasian EHE, as evidenced by a shift in its dominant mode around 2000. After that, the frequency and variability of EHE are significantly increased (Supplementary Fig. 1). More spring EHE could have devastating influences on the ecosystems and human activities31,32,33. Therefore, advanced prediction of spring Eurasian EHE variation is crucial for natural disaster prevention.

Previous studies have indicated that the dynamical prediction of climate over mid-to-high latitude is a big challenge48,49,50,51. The aforementioned BK sea ice anomalies lead the variability of spring EHE over Eurasia by one season. Could the BK sea ice signal be useful for the prediction of the spring EHE dipole mode? To answer this question, the method of leave-one-out cross-validated is used to hindcast the interannual variation of spring EHE dipole mode index based on the winter BK sea ice index and linear regression. The hindcasted index of spring EHE dipole mode shows good similarity with the observed one (Fig. 6). The correlation between hindcasted and observed indices is 0.71, significant at the 99.9% confidence level. This result suggests that the winter BK sea ice could explain about 50% of the interannual variation of spring EHE dipole mode. Our study here presents new insights into the prediction of spring Eurasian climate extremes derived from cryospheric variability.

Data and methods

Datasets

Daily maximum temperature data are derived from the Climate Prediction Center (CPC) Global Unified Temperature provided by the NOAA on a 0.5° × 0.5° grid. The monthly SIC data are derived from the Hadley Centre Sea Ice and Sea Surface Temperature data set (HadISST)52 on a 1° × 1° grid. The monthly geopotential height, temperature, zonal and meridional winds at standard pressure levels, total cloud cover, and surface heat fluxes data are from the National Centers for Environmental Prediction–Department of Energy (NCEP–DOE) reanalysis 2 dataset53 on a 2.5° × 2.5° grid.

EHE definition

We use TX90p as the extreme temperature index to represent the changes in EHE, which is calculated as the percentage of days above the 90th percentile based on daily maximum temperatures for the reference period of 1981-2010. The TX90p is recommended by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) Expert Team of Climate Change, Detection, Monitoring and Index (ETCCDMI). More details can be found at http://etccdi.pacificclimate.org/list_27_indices.shtml.

Blocking frequency definition

According to the definition of instantaneous blocking54, we detect blocking days in each grid point that satisfy the reversal of 500-hPa height gradient specified by this method. Then, the spring blocking frequency in each grid point is calculated as the percentage of total blocking days in spring to total spring days (92 days).

Winter BK sea ice index and spring EHE dipole mode index

The winter BK sea ice index is defined as the normalized regional-mean SIC over the BK region (76°−83°N, 11°−75°E, and 68°−76°N, 50°−75°E) in Fig. 1b. The spring EHE dipole mode index is defined as the normalized difference in regional-mean EHE between the red boxes (35°−57°N, 20°−120°E and 50°−70°N, 125°−165°E) and blue box (60°−76°N, 20°−120°E) in Fig. 1a.

Statistical analysis and significance

The main statistical tools utilized in this study include SVD analysis, EOF analysis, leave-one-out cross-validation analysis, moving t-test analysis, correlation analysis, linear regression analysis, and composite analysis. The analysis period in this study is the common period of the aforementioned datasets: December 1979 to May 2021. To study the interdecadal changes in winter sea ice and spring EHE, we divided the time period into two subperiods, called pre-2000 and post-2000. The two subperiods in the raw data analysis are 1980–2000 and 2001–2021. To extract the interannual variations of variables, all data are high-pass filtered by 7-year running mean before analyses. The first and last 3 years of the filtered time series are discarded; therefore, the two subperiods of pre-2000 and post-2000 for analysis on interannual variations are 1983–2000 and 2001–2018. The two-tailed F-test is used for composite analysis on sample variance. The two-tailed Student’s t test is used for moving t-test analysis, correlation analysis, linear regression analysis, and composite analysis on sample means.

The cross wavelet transform55 is adopted to explore the co-variability and relative phase between winter BK sea ice and spring Eurasian EHE in time-frequency space. The WAF56 is used to diagnose the three–dimensional propagation of stationary Rossby wave propagation associated with winter BK sea ice. The RWS57 is applied to detect the origin of the wave train. The EP flux is used to diagnose the vertical propagation of wave and the flux divergence is used to examine the wave forcing on the zonal wind44,58.

Data availability

CPC Global Unified Temperature dataset are publicly available at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cpc.globaltemp.html. NCEP-DOE Reanalysis 2 dataset are available at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.ncep.reanalysis2.html. HadISST dataset are available at https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst/data/download.html.

Code availability

The computer codes that support the analysis within this paper are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Comiso, J., Parkinson, C., Gersten, R. & Stock, L. Accelerated decline in the Arctic sea ice cover. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L01703 (2008).

Cavalieri, D. & Parkinson, C. Arctic sea ice variability and trends, 1979–2010. The Cryosphere 6, 881–889 (2012).

Rothrock, D., Yu, Y. & Maykut, G. Thinning of the Arctic sea-ice cover. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 3469–3472 (1999).

Kwok, R. Arctic sea ice thickness, volume, and multiyear ice coverage: losses and coupled variability (1958–2018). Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 105005 (2018).

Markus, T., Stroeve, J. & Miller, J. Recent changes in Arctic sea ice melt onset, freezeup, and melt season length. J. Geophys. Res. 114, C12024 (2009).

Stroeve, J., Markus, T., Boisvert, L., Miller, J. & Barrett, A. Changes in Arctic melt season and implications for sea ice loss. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 1216–1225 (2014).

Onarheim, I., Eldevik, T., Årthun, M., Ingvaldsen, R. & Smedsrud, L. Skillful prediction of Barents Sea ice cover. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 5364–5371 (2015).

Onarheim, I., Eldevik, T., Smedsrud, L. & Stroeve, J. Seasonal and regional manifestation of Arctic sea ice loss. J. Clim. 31, 4917–4932 (2018).

Honda, M., Inoue, J. & Yamane, S. Influence of low Arctic sea‐ice minima on anomalously cold Eurasian winters. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L08707 (2009).

Petoukhov, V. & Semenov, V. A link between reduced Barents-Kara sea ice and cold winter extremes over northern continents. J. Geophys. Res. 115, D21111 (2010).

Inoue, J., Hori, M. & Takaya, K. The role of Barents sea ice in the wintertime cyclone track and emergence of a warm-Arctic cold-Siberian anomaly. J. Clim 25, 2561–2568 (2012).

Cohen, J., Furtado, J., Barlow, M., Alexeev, V. & Cherry, J. Arctic warming, increasing snow cover and widespread boreal winter cooling. Environ. Res. Lett. 7, 014007 (2012).

Tang, Q., Zhang, X., Yang, X. & Francis, J. Cold winter extremes in northern continents linked to Arctic sea ice loss. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 014036 (2013).

Mori, M., Watanabe, M., Shiogama, H., Inoue, J. & Kimoto, M. Robust Arctic sea-ice influence on the frequent Eurasian cold winters in past decades. Nat. Geosci. 7, 869–873 (2014).

Vihma, T. Effects of Arctic sea ice decline on weather and climate: a review. Surv. Geophys. 35, 1175–1214 (2014).

Kug, J. et al. Two distinct influences of Arctic warming on cold winters over North America and East Asia. Nat. Geosci. 8, 759–762 (2015).

Overland, J. et al. The melting Arctic and midlatitude weather patterns: are they connected? J. Clim 28, 7917–7932 (2015).

Gao, Y. et al. Arctic sea ice and Eurasian climate: a review. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 32, 92–114 (2015).

Shepherd, T. Effects of a warming Arctic. Science 353, 989–990 (2016).

Wu, B., Yang, K. & Francis, J. A cold event in Asia during January–February 2012 and its possible association with Arctic sea ice loss. J. Clim 30, 7971–7990 (2017).

He, S., Xu, X., Furevik, T. & Gao, Y. Eurasian cooling linked to the vertical distribution of Arctic warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087212 (2020).

Liu, J., Curry, J., Wang, H., Song, M. & Horton, R. Impact of declining Arctic sea ice on winter snowfall. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 4074–4079 (2012).

Wegmann, M. et al. Arctic moisture source for Eurasian snow cover variations in autumn. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 054015 (2015).

Bailey, H. et al. Arctic sea-ice loss fuels extreme European snowfall. Nat. Geosci. 14, 283–288 (2021).

Wang, H., Chen, H. & Liu, J. Arctic sea ice decline intensified haze pollution in eastern China. Atmos. Oceanic Sci. Lett. 8, 1–9 (2015).

Li, F. et al. Arctic sea-ice loss intensifies aerosol transport to the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 1037–1044 (2020).

Cohen, J. et al. Recent Arctic amplification and extreme mid-latitude weather. Nat. Geosci. 7, 627–637 (2014).

Alexander, L. et al. Global observed changes in daily climate extremes of temperature and precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. 111, D05109 (2006).

Flanner, M. et al. Springtime warming and reduced snow cover from carbonaceous particles. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 2481–2497 (2009).

Ding, Z. & Wu, R. Quantifying the internal variability in multi-decadal trends of spring surface air temperature over mid-to-high latitudes of Eurasia. Clim. Dyn. 55, 2013–2030 (2020).

Augspurger, C. K. Reconstructing patterns of temperature, phenology, and frost damage over 124 years: Spring damage risk is increasing. Ecology 94, 41–50 (2013).

Ying, H. et al. Effects of spring and summer extreme climate events on the autumn phenology of different vegetation types of Inner Mongolia, China, from 1982 to 2015. Ecological Indicators 111, 105974 (2020).

Schwarz, L. et al. The health burden fall, winter and spring extreme heat events in the in Southern California and contribution of Santa Ana Winds. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 054017 (2020).

Copernicus. Heat in Siberia. [Press release]. https://climate.copernicus.eu/esotc/2020/heat-siberia. (2021).

Brunner, L., Hegerl, G. & Steiner, A. Connecting atmospheric blocking to European temperature extremes in spring. J. Clim. 30, 585–594 (2017).

Kumar, A., Yadav, J. & Mohan, R. Spatio-temporal change and variability of Barents-Kara sea ice, in the Arctic: ocean and atmospheric implications. Sci. Total Environ. 753, 142046 (2021).

Dai, A., Luo, D., Song, M. & Liu, J. Arctic amplification is caused by sea-ice loss under increasing CO2. Nat. Commun. 10, 121 (2019).

Luo, D. et al. Impact of Ural blocking on winter warm Arctic–cold Eurasian anomalies. Part I: Blocking-induced amplification. J. Clim 29, 3925–3947 (2016).

Nakamura, T. et al. A negative phase shift of the winter AO/NAO due to the recent Arctic sea‐ice reduction in late autumn. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 3209–3227 (2015).

Kim, B. et al. Weakening of the stratospheric polar vortex by Arctic sea-ice loss. Nat. Commun. 5, 4646 (2014).

Zhang, P. et al. A stratospheric pathway linking a colder Siberia to Barents-Kara Sea sea ice loss. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat6025 (2018).

Jaiser, R., Dethloff, K. & Handorf, D. Stratospheric response to Arctic sea ice retreat and associated planetary wave propagation changes. Tellus A 65, 19375 (2013).

Charney, J. & Drazin, P. Propagation of planetary-scale disturbances from the lower into the upper atmosphere. J. Geophys. Res. 66, 83–109 (1961).

Edmon, H. Jr, Hoskins, B. & McIntyre, M. Eliassen-Palm cross sections for the troposphere. J. Atmos. Sci. 37, 2600–2616 (1980).

Baldwin, M. & Dunkerton, T. Propagation of the Arctic Oscillation from the stratosphere to the troposphere. J. Geophys. Res. 104, 30937–30946 (1999).

Baldwin, M. & Dunkerton, T. Stratospheric harbingers of anomalous weather regimes. Science 294, 581–584 (2001).

Pfahl, S. & Wernli, H. Quantifying the relevance of atmospheric blocking for co-located temperature extremes in the Northern Hemisphere on (sub-) daily time scales. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L12807 (2012).

Spencer, H. & Slingo, J. The simulation of peak and delayed ENSO teleconnections. J. Clim. 16, 1757–1774 (2003).

Cohen, J. & Fletcher, C. Improved skill of Northern Hemisphere winter surface temperature predictions based on land–atmosphere fall anomalies. J. Clim 20, 4118–4132 (2007).

Hardiman, S., Kushner, P. & Cohen, J. Investigating the ability of general circulation models to capture the effects of Eurasian snow cover on winter climate. J. Geophys. Res. 113, D21123 (2008).

Sun, J. & Chen, H. A statistical downscaling scheme to improve global precipitation forecasting. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 117, 87–102 (2012).

Rayner, N. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 4407 (2003).

Kanamitsu, M. et al. NCEP–DOE AMIP-II reanalysis (R-2). Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 83, 1631–1644 (2002).

Davini, P., Cagnazzo, C., Gualdi, S. & Navarra, A. Bidimensional diagnostics, variability, and trends of Northern Hemisphere blocking. J. Clim 25, 6496–6509 (2012).

Grinsted, A., Moore, J. & Jevrejeva, S. Application of the cross wavelet transform and wavelet coherence to geophysical time series. Nonlin. Processes Geophys. 11, 561–566 (2004).

Plumb, R. On the three-dimensional propagation of stationary waves. J. Atmos. Sci. 42, 217–229 (1985).

Sardeshmukh, P. & Hoskins, B. The generation of global rotational flow by steady idealized tropical divergence. J. Atmos. Sci. 45, 1228–1251 (1988).

Andrews, D. On the interpretation of the Eliassen-Palm flux divergence. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 113, 323–338 (1987).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 41991281 and 41825010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S. conceived of the study. S.L. and S.Y. conducted the analysis under J.S.’s instruction. J.S. and S.L. wrote the manuscript. J.C. made suggestions and edits to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Joe Aslin, Heike Langenberg.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, J., Liu, S., Cohen, J. et al. Influence and prediction value of Arctic sea ice for spring Eurasian extreme heat events. Commun Earth Environ 3, 172 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00503-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00503-9

This article is cited by

-

Synergistic effects of Arctic amplification and Tibetan Plateau amplification on the Yangtze River Basin heatwaves

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2024)

-

Assessment of Arctic sea ice simulations in cGENIE model and projections under RCP scenarios

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Impacts of early-winter Arctic sea-ice loss on wintertime surface temperature in China

Climate Dynamics (2024)

-

Exceptionally Cold and Warm Spring Months in Kraków Against the Background of Atmospheric Circulation (1874–2022)

Pure and Applied Geophysics (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.