Abstract

Atmospheric deposition is a major source of the nutrients sulfur and selenium to agricultural soils. Air pollution control and cleaner energy production have reduced anthropogenic emissions of sulfur and selenium, which has led to lower atmospheric deposition fluxes of these elements. Here, we use a global aerosol-chemistry-climate model to map recent (2005–2009) sulfur and selenium deposition, and project future (2095–2099) changes under two socioeconomic scenarios. Across the Northern Hemisphere, we find substantially decreased deposition to agricultural soils, by 70 to 90% for sulfur and by 55 to 80% for selenium. Recent trends in sulfur and selenium concentrations in USA streams suggest that catchment mass balances of these elements are already changing due to the declining atmospheric supply. Sustainable fertilizer management strategies will need to be developed to offset the decrease in atmospheric nutrient supply and ensure future food security and nutrition, while avoiding consequences for downstream aquatic ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In addition to pressures from an increasing population and climate change, a fundamental challenge for intensive agriculture is ensuring an adequate supply of nutrients1,2,3,4. Sulfur (S) availability is central to food security, as it is an essential macro-nutrient for crop health and yield5,6. While selenium (Se), which is positioned below S on the periodic table and shares many chemical properties with S, is not thought to be required for plant growth, it is an essential dietary element for humans and livestock7,8. In many regions, low Se in crops can cause micronutrient deficiencies, with an estimated 0.5–1 billion people worldwide having inadequate Se intake9. Atmospheric deposition acts as a major source of S and Se to agricultural soils6,10. Sulfur and Se are emitted to the atmosphere by natural sources, including volcanoes and the marine and terrestrial biosphere, and anthropogenic activities, such as fossil fuel combustion, metal smelting, and manufacturing11,12. Until the 1990s, high levels of atmospheric S deposition in industrialized countries caused acidification of aquatic systems, decline of fish populations, and degradation of forests13,14. Over the last few decades, improvements in air pollution control and reductions in coal combustion in North America and Europe have reduced S emissions and deposition, decreased concentrations of fine particulate matter in the air, and enabled recovery of ecosystems damaged by acid rain5,6,14. Shifts away from coal energy generation are also essential for meeting the climate change mitigation goals of the Paris Agreement15. However, from an agricultural perspective, the decreases in deposition have raised questions about future deficiencies of S and Se.

Natural processes that replenish nutrients in agricultural soils are generally slower than the anthropogenic removal of nutrients through crop harvest, leading to a decline of soil nutrients2,16. Although this issue has been well studied for macronutrients such as nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P), attention has only been recently drawn toward the mass balances of S and Se in agricultural soils6,17,18. Previous work has highlighted the increasing prevalence of S deficiency in agricultural soils in the USA and, consequently, growing demand for S fertilizers, as anthropogenic S emissions decline5,6,19. Surveys in the UK and Germany have suggested that 23% and 40% of soils are at a high risk for S deficiency, respectively20,21. Even less research has focused on Se, although one study in the UK reported declines of Se in pastures due to decreases in atmospheric Se deposition22. A recent study using machine-learning algorithms forecasted declines (mean loss = 8.4%) in soil Se concentrations by the end of the twenty-first century, driven by reduced soil Se retention associated with climate change17. The driving mechanism for soil Se losses is that increasing aridification shifts the speciation of Se to more oxidized species that are weaker bound in soil and leach more readily during precipitation events. However, future changes in atmospheric inputs of Se to soils were not considered, since mapped estimates of atmospheric Se deposition were not previously available. Here, we calculate future changes in atmospheric S and Se deposition using a global aerosol–chemistry–climate model, SOCOL-AER, which includes the first atmospheric Se chemistry submodel of its kind10,12,23,24. The model simulates the emissions, transformations, atmospheric transport, and wet and dry deposition of S and Se. These projections of atmospheric deposition can inform future efforts to characterize and quantify the impacts of anthropogenic activities and climate change on nutrient availability.

We compare modeled deposition of S and Se in the recent past (2005–2009) to future simulations (2095–2099) under two Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) scenarios that span the range of future climate change projections: SSP1–2.6, where sustainably-driven development maintains global warming below 2 °C relative to preindustrial levels, and SSP5–8.5, where fossil fuel-driven development leads to warming of about 5 °C25. Whereas anthropogenic emissions of sulfur dioxide (SO2) are provided directly by the SSP scenarios, we estimate emissions of Se by applying scaling factors to SO2. The scaling approach successfully matches observed trends in particulate Se10 and is consistent with the available bottom-up Se emission inventories from several countries (Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary Figs. 10–13).

Results and discussion

Projected and observed declines in S and Se deposition

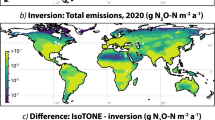

In the recent period (2005–2009), the model predicts hotspots of Se deposition in East Asia, Eastern Europe, and Eastern USA, areas of high anthropogenic emissions, as well as degassing volcanoes (e.g., Mt. Etna, Italy) (Fig. 1a). Selenium deposition is relatively high over most of the ocean, due to volatile marine biogenic emissions. Since atmospheric Se is mainly transported in submicron particles, the dominant deposition pathway is wet deposition (~80% of total deposition)10. Therefore, dry areas (eastern ocean basins and the Sahara) have particularly low Se deposition. Recent S deposition shows a similar spatial pattern to Se (Supplementary Fig. 2a), except that anthropogenic emissions are relatively more important in the S budget than for Se (60% vs. 34% of total emissions, Supplementary Table 1).

a Distribution of atmospheric Se deposition in the recent period, 2005–2009. b Modeled (red line) and observed (blue line) trend in wet Se deposition, averaged over six measurement stations in Ontario, Canada. Error bars indicate the 2σ variability between measurement stations. c Relative difference in Se deposition from the recent period (2005–2009) to the future (2095–2099) under the SSP1–2.6 scenario (for SSP5–8.5, see Supplementary Fig. 1). White grid cells indicate that the mean change is smaller than the 2σ interannual variability from the 2005 to 2009 simulation. Pie charts illustrate the Se source contributions to deposition for each continent for recent and future periods, with pie area proportional to total continental deposition.

Since the 1980s, anthropogenic emissions of S have decreased in North America and Europe, due to shifts away from coal energy generation26 and increasing implementation of air pollution control technology, including post-combustion scrubbers to capture SO2 emissions, switching from high S coal to low S coal, and removal of S from oil before combustion27. Due to the chemical similarities between S and Se, Se emissions are reduced concomitantly by these SO2 control technologies28. The model matches the observed declines in Se deposition in recent decades at the only sites where long-term deposition data are available, in Ontario, Canada (modeled = −41 ± 3% per decade, observed = −38 ± 13% per decade) and Western Europe (modeled = −38 ± 10% per decade, observed = −47 ± 18% per decade) (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 8). In a previous study comparing the model with a larger observational dataset for particulate Se, we found that 85% of modeled Se concentrations are within a factor of 2 of observations and the model captures the observed decline in particulate Se in North America10. Although long-term trends of Se are not available outside of Europe and North America, the model showed good agreement (R2 = 0.67) with shorter-term Se measurements from other continents10. In China and India, S and Se deposition approximately doubled between 1980s and 2000s (Supplementary Figs. 1b and 2b), due to increases in coal combustion29. More recently, emission controls have been implemented in China, resulting in a 62% decline of SO2 emissions between 2010 and 201730.

Under the two future socioeconomic scenarios, SSP1–2.6 and SSP5–8.5, global Se deposition is projected to decrease (−31% and −23%, respectively) by the end of the twenty-first century compared to 2005–2009 values (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1d). The projected decrease in deposition is particularly noteworthy over Asia, North America, and Europe, because anthropogenic emissions are mainly located in these continents. The underlying explanation for the decrease in S and Se emissions in SSP1–2.6 is a rapid transition away from fossil fuel energy generation toward renewable energies and increased air pollution controls. In SSP5–8.5, further air pollution control technology is implemented and energy production shifts from coal to natural gas, which contains less S and Se11,25. Although only two future scenarios were simulated in this study, analysis of SO2 emission projections suggests similar outcomes for other SSP scenarios (Supplementary Fig. 9). Certain areas over the ocean display increases in Se deposition in future scenarios, including the Eastern Pacific and Southern Ocean (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1d). These increases are stronger under SSP5–8.5 than SSP1–2.6 and are caused by projected changes in climate, including precipitation shifts and enhanced marine biogenic emissions due to sea ice decline (Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). Global S deposition shows steeper declines during the twenty-first century than global Se deposition (−56% vs. −31% for SSP1–2.6; −43% vs. −23% for SSP5–8.5), due to greater contributions from anthropogenic sources for total S emissions than Se (Supplementary Table 1).

Our model employs source tracking for Se to attribute deposition to the different sources: anthropogenic activities, volcanoes, marine biosphere, and terrestrial biosphere. During the recent period (2005–2009), most Se deposition over Asia, North America, and Europe is attributed to anthropogenic sources (75%), whereas Africa, South America, and Australia are dominated by biogenic and volcanic sources of Se (79%) (Fig. 1c). Marine biogenic sources contribute significantly to Se deposition in certain continental areas (e.g., 35% of Australian deposition in 2005–2009), illustrating the long-range transport of Se23. By the end of the twenty-first century, anthropogenic contributions to deposition diminish in the Northern Hemisphere (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Figs. 3–5). For SSP5–8.5, anthropogenic sources are still projected as the dominant contributor to deposition in certain regions, such as the Indo-Gangetic Plain, the Arabian Peninsula, Western Europe, and Northeastern China (Supplementary Fig. 5). Overall, however, biogenic and volcanic sources will become the major contributor (53–98%) to Se deposition over all continents under both future scenarios.

Impacts of deposition trends on agricultural regions

Because atmospheric deposition is the major input of S and Se to soils in many regions globally6,10,18,22, the projected changes in deposition will impact the mass balance of these nutrients in agricultural soils. We quantify trends in the deposition of S and Se to agricultural soils by calculating median deposition over model grid cells that are covered by >25% croplands or pastures31 (Fig. 2). As the deposition to agricultural soils in the Southern Hemisphere is less influenced by anthropogenic emissions, S and Se deposition over Africa, Australia, and South America will decrease only modestly in the future, ranging from 20 to 40% for S and 3 to 25% for Se. On the other hand, agricultural soils in Asia, North America, and Europe show strong decreases at the end of the twenty-first century from recent (2005–2009) values for S (85–90% for SSP1–2.6; 70–75% for SSP5–8.5) and Se (70–80% for SSP1–2.6; 55–65% for SSP5–8.5). These projected declines are on par with the relative changes in S deposition between the 1980s and 2000s for agricultural regions in Europe and North America (−70% and −35%, respectively) (Fig. 2), when agricultural S deficiencies became more prevalent. Therefore, we expect that if agricultural practices do not change, S deficiencies in plants and Se deficiencies in livestock and humans could become more frequent and severe in the Northern Hemisphere due to the substantial depletion of the atmospheric S and Se supply.

Median S and Se deposition over agricultural grid cells for different continents and time periods. Error bars indicate the interquartile range. Agricultural grid cells are defined by selecting grid cells covered by >25% croplands or pastures in the Ramankutty et al.31 database. For tabulated numerical data, see Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

Comparing current conditions with the end of the twenty-first century, atmospheric S and Se inputs to soil will decline, retention of Se in soils will decrease due to aridification with climate change17, and food demand will increase due to a growing global population2. The decline in the atmospheric source to soils, coupled with the enhanced soil Se losses (increased leaching and crop production), will increase the risk of S and Se deficiencies, unless adequate S and Se fertilizer management strategies are developed and implemented (Fig. 3a, b). Expanding existing strategies of S and Se fertilizer use8,32 for large-scale deployment would pose several logistical, economic, and environmental challenges. Known Se resources could be exhausted within 40 years if standard fertilization rates (20 g Se ha−1) are applied to all wheat fields32. Sulfate and selenate, the most common S and Se species in inorganic fertilizers, compete for the same uptake pathway in plants, meaning that excess sulfate in soil can limit Se uptake in crops8. A significant fraction of fertilized S and Se will not be assimilated by crops and can leach into surface waters6,8. Runoff of S and Se poses risks to ecosystems (Fig. 3c), as Se is toxic at high concentrations8,33 and excess S degrades soils through acidification, can result in sulfide phytotoxicity, and enhanced mercury methylation downstream in drainage waters6,14. The extent to which S and Se are mobilized from soil systems would depend on the local environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, precipitation, and land use) and soil properties (e.g., pH, organic carbon content, and clay content)17. In general, there is a strong need for studies that assess S and Se mass balances at a variety of scales (field plots, watersheds, and larger regions) and geographic locations. Other agricultural management practices could also be employed to increase the efficiency of S and Se uptake by plants, such as conventional breeding or genetic engineering34,35, thereby reducing the required amount of fertilizer inputs.

a Sulfur and Se fluxes in agricultural soils in the recent period, when atmospheric S and Se deposition have been the dominant source to soils. Arrow width is semi-quantitative in illustrating the relative magnitudes of fluxes. Soil processes are simplified in the diagram and are discussed more comprehensively in previous reviews67,68,69,70. b In the future, S and Se deposition is projected to decrease, while at the same time crop production must increase to satisfy rising food demand. Fertilizer use may become the dominant S and Se source to agricultural soils in the future, possibly enhancing S and Se runoff. c Fertilizer S and Se inputs have downstream ecological consequences. Sulfur inputs can lead to acidification, soil cation depletion, sulfide toxicity, and mercury methylation, whereas Se inputs can cause harmful algae blooms and toxic conditions for organisms.

S and Se mass balance in USA watersheds

To illustrate the impact of transient changes in deposition and agricultural inputs on the surface Se mass balance at a regional scale, we analyzed stream concentrations of Se (2000–2020) from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) database (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 15). Watersheds in the Northeastern USA show declines (likelihood of decreasing trend >92%) in Se stream fluxes (−15 to −28%) that follow steeper Se deposition declines in these watersheds (−39 to −58%). In these basins, Se deposition fluxes are greater or similar in magnitude to the stream Se fluxes (Supplementary Fig. 15), implying that atmospheric Se deposition is a major source in the surface mass balance. Since the declining stream Se trends deviate from nitrate and orthophosphate trends in the Northeastern USA watersheds, it is unlikely that wastewater or agricultural releases are responsible for the decline. Concentration-discharge relationships of S and Se in these basins also support the hypothesis that declining atmospheric inputs drive the stream flux declines (Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary Figs. 16–21).

Comparison between the relative trends in modeled Se deposition fluxes (Sedep), dashed blue line, over watersheds in the USA and flow-normalized fluxes of dissolved Se (Seriv), sulfate (Sriv), nitrate (Nriv), and orthophosphate (Priv), colored solid lines. Detailed information about the stream flux analysis and trends from other basins can be found in the Supplementary Discussion. Land cover data for 2011 are sourced from the USGS National Land Cover Database (https://doi.org/10.5066/P937PN4Z).

In contrast, basins in the Midwestern USA show increasing trends in the riverine S and Se (likelihood of increasing trend >90%) that more closely follow nitrate and orthophosphate trends and are inconsistent with decreasing atmospheric deposition trends. The substantial coverage of croplands in these basins (ranging between 21 and 32% of pixels) suggests that agricultural inputs could be driving the trends in riverine S and Se. Even though Se is not widely intentionally used in fertilizer, agricultural amendments derived from phosphate rocks contain trace amounts of selenium36. In the San Joaquin River Basin, an area known for high Se concentrations in agricultural irrigation drainage water causing toxicity in animals37, riverine Se fluxes have strongly decreased (−73%) from 2008 to 2019 (likelihood of decreasing trend = 97%). The recent decreases in Se are likely driven by restoration projects in the region that aim to reduce flows of agricultural runoff to the river38.

Undeniably, the trends in stream fluxes could be caused by combinations of source (e.g., wastewater, agriculture, deposition, geological) trends and sink (e.g., retention of nutrient in the catchment) behavior, as well as hydrological changes in the basin. Continued monitoring and analysis of stream concentrations will be needed to reveal further insights into the response of watersheds to the decreasing atmospheric inputs of S and Se, and/or potentially increasing inputs from fertilizers6,39. Since our model projects decreases of S and Se deposition across the Northern Hemisphere (Fig. 2), a critical next step is to conduct mass balance calculations for Asian and European catchments.

Outlook

We recognize that any impacts of declining atmospheric S and Se deposition on nutrition and food security will also depend on land management, crop type, and geochemical factors affecting speciation and bioavailability of these elements in soil. In addition, there is currently no consensus regarding the impact of climate change on biogenic emissions of sulfur40 and Se, which can affect both the sources and sinks of these elements in agricultural soils in the future. Further work characterizing the response of biogenic S and Se emissions to climate change and ocean acidification will refine our deposition projections. We emphasize that past and projected reductions in coal combustion emissions of S, Se, and other co-pollutants (e.g., carbon dioxide, methane, nitrogen oxides, mercury, and arsenic) will be effective for climate change mitigation and human and ecosystem health41. However, innovative strategies will need to be developed—integrating knowledge from agriculture, environmental sciences, and economics—to sustainably resupply agricultural soils with S and Se as atmospheric sources decline.

Methods

SOCOL-AER model

We use the aerosol–chemistry–climate model SOCOL-AERv212,24,42, which comprises the chemical submodel MEZON43, the dynamical submodel ECHAM544, and the size-resolving sulfate aerosol module AER45. Atmospheric Se chemistry was previously implemented in the SOCOL-AER model10,23. Including the Se module, SOCOL-AER includes around 89 gas phase chemical species, 299 gas phase reactions, 80 particulate tracers, and 16 heterogeneous reactions, representing a comprehensive description of atmospheric chemistry. Gas phase Se reaction rate constants are obtained from Table 2 in Feinberg et al.23 and gas phase S reaction rate constants are taken from the NASA/JPL Data Evaluation46. SOCOL-AER tracks the sulfate particle size distribution in 40 size bins between 0.39 nm and 3.2 µm. In terms of microphysical processes, the model considers aerosol sedimentation, nucleation, condensation, evaporation, and coagulation. Uptake of oxidized Se compounds in S aerosols is calculated by determining the gas phase diffusion rate and assuming a mass accommodation coefficient of 1. Wet and dry deposition in SOCOL-AER are based on state-of-the-art schemes that interact with grid cell meteorology and surface properties47,48,49. Previous studies have shown very good agreement (R2 ~0.6–0.7) between SOCOL-AER simulations and measurements of S deposition24 and Se deposition10, validating the application of the model in this study for predictions of future deposition.

For this study, we run the model in T42 resolution (~2.8° × 2.8°) and 39 vertical levels up to 80 km. The model is run with an operator splitting approach: a 2 h time step is used for the chemistry and radiation schemes, 15 min for dynamics and deposition, and 6 min for aerosol microphysics schemes.

Boundary conditions

Past emissions of anthropogenic SO2 to the atmosphere are taken from the Community Emissions Data Systems29, which were developed for Coupled Model Intercomparison Project—Phase 6 (CMIP6). Future projections of anthropogenic SO2 emissions are sourced from the CMIP6 project ScenarioMIP, which uses integrated assessment models to predict future trends in emissions for a subset of SSP scenarios25. Marine dimethyl sulfide (DMS) concentrations are prescribed by an observation-based climatology50 and sea-to-air transfer is determined using a wind-based parametrization51. Volcanic degassing is assumed to occur in grid boxes where volcanoes are located and emits a total of 12.6 Tg S year–1 52,53. Mixing ratio boundary conditions are applied for the gas phase species hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and carbonyl sulfide (OCS), which are set to 30 and 500 pptv, respectively45,54.

Emissions of Se in SOCOL-AER are based on the spatial distribution of S emissions, with scaling factors between S and Se derived from available measurements using Bayesian inversion methods10. Anthropogenic emissions of Se are calculated by scaling anthropogenic SO2 emissions using a mass ratio of 1.9 × 10–4 g Se (g S)–1. We assume the same S-to-Se scaling factor for future projections and historical simulations, given that using a constant S-to-Se scaling factor succeeded in matching observed trends of particulate Se10. Marine dimethyl selenide (DMSe) concentrations are scaled from the DMS climatology50 using a molar ratio of 2.1 × 10–4 mol Se (mol S)–1, as derived in the Bayesian inversion10. As with DMS, DMSe emissions are calculated using a wind-driven parametrization51. Volcanic degassing S emissions are scaled by 3.0 × 10–4 g Se (g S)–1 to yield volcanic Se emissions, which total 3.8 Gg Se year–1. Terrestrial biogenic emissions of Se are included using the spatial distribution of volatile organic carbon (VOC) emissions from the MEGAN-MACC inventory55, scaled to a global total of 5.0 Gg Se year–1 10.

Since SOCOL-AER is an atmosphere-only model, we prescribe sea ice coverage and sea surface temperatures using observed data from the Hadley Centre56 for the past periods (1980–1985 and 2004–2009). For the future scenarios (SSP1–2.6 and SSP5–8.5), we prescribe sea ice coverage and sea surface temperatures using 2094–2099 simulation data from the CESM1(CAM5) model for the analogous Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) scenarios, RCP2.6 and RCP8.557, since coupled-ocean simulations using the new SSP scenario forcings were not yet available. Other boundary conditions (greenhouse gas forcing; ozone-depleting substances; NOx, CO, and VOC emissions) are taken from the specifications of Chemistry-Climate Model Initiative REF-C2 sensitivity simulations for RCP2.6 and RCP8.558,59.

Model simulations

To compare with future projections with past simulations, we model three different periods: past (1980–1985), recent (2004–2009), and future (2094–2099). Each simulation consists of a 1 year spinup for the atmospheric S(e) species and 5 year that are used for analysis. The model was initialized with chemical fields from REF-C2 sensitivity simulations in SOCOL58,59, to reduce the time necessary for model equilibration. The future period is modeled with three scenarios: SSP1–2.6, SSP5–8.5, and SSP5–8.5 under recent climate conditions. To simulate SSP5–8.5 under recent climate conditions, we include anthropogenic SO2 and Se emissions from the SSP5–8.5 scenario for 2094–2099, but force the model with greenhouse gas concentrations, sea surface temperatures, sea ice coverage, and solar forcing from 2004 to 2009.

We track the influence of Se sources on deposition for the recent period, SSP1–2.6, and SSP5–8.5. To separate the contribution of each Se source category (anthropogenic activities, volcanoes, marine biosphere, and terrestrial biosphere), we run four individual simulations, each with one source category turned on and all others turned off. Because Se does not have any significant impacts on atmospheric chemistry or climate due to its low concentration23, we assume linear additive behavior between the four simulations. To identify the contribution of a certain source category to Se deposition, we divide the Se deposition in an individual source category simulation by total Se deposition summed over all four source category simulations. We decouple interactions between chemistry and radiation, to ensure that each of the four individual source category simulations have the same meteorology, which increases the signal-to-noise ratio.

To compare with Se observations (Figs. 1b and 4 and Supplementary Figs. 8 and 15), we use transient simulations for 1970–2017 that were conducted for Feinberg et al.10. These simulations were run in nudged mode for 1979–2017, meaning that model temperature, surface pressure, divergence, and vorticity were forced toward ERA-Interim reanalysis data60. As opposed with the free-running simulations that were explained previously, the meteorology in nudged simulations should follow observed meteorology closer, and therefore they are more appropriate for comparison with observed quantities.

Canadian deposition observations

We compare the model with measured wet Se deposition trends for 2003–2017 from six Ontarian sites in the Canadian National Atmospheric Chemistry database (http://donnees.ec.gc.ca/data/air/monitor/monitoring-of-atmospheric-precipitation-chemistry/metals-in-precipitation/): Burlington (43.4° N, 79.8° W), Rock Point (42.8° N, 79.5° W), St. Clair (42.4° N, 82.4° W), Point Pelee (42.0° N, 82.5° W), Sibley (48.5° N, 88.7° W), and Point Petre (43.8° N, 77.1° W). For comparison with measurements, we interpolate the model horizontally to the coordinates of the measurement station. We summarize the regional modeled and observed trend by averaging all available sites for each year and calculate the standard deviation between sites.

Stream flux analysis

All stream water data were downloaded and analyzed using the R packages dataRetrieval and EGRET61. The source of the stream concentration samples and daily discharge data is the USGS National Water Information System database (https://doi.org/10.5066/F7P55KJN). The EGRET package includes an implementation of the Weighted Regressions on Time Discharge and Season (WRTDS) method62. This method can be used to calculate monthly flow-normalized fluxes of chemical constituents. Flow-normalization removes the influence of interannual flow variations on the chemical flux, revealing the underlying trends in the watershed, which are often caused by anthropogenic factors63. In WRTDS models, the chemical constituent of interest is a function of discharge, seasonality, the long-term trend, and a random component. The method is usually well suited for time series of a decade or longer and a sampling frequency of at least six samples per year61. We therefore only selected sites that had Se measurements with sufficient sampling frequency and time span, for a total of 18 sites (Supplementary Fig. 14 and Supplementary Table 4). At each of these sites, we calculated WRTDS models for the flow-normalized fluxes of dissolved Se (parameter ID 01145) using available water quality samples and daily discharge data. WRTDS models were constructed using the default parameters of EGRET: half-window widths of 2 (in log discharge units) for discharge, 7 year for temporal trends, and 0.5 year for seasonality. Annual averages of fluxes are taken over the calendar year (January–December) to compare with modeled deposition fluxes. We also constructed WRTDS models of sulfate (SO42−, parameter ID 00945), nitrate (NO3−, 00618), and orthophosphate (PO43−, 00660) at sites where these parameters were available, in order to compare Se trends with other nutrients. We compare Se stream flux trends with modeled atmospheric Se deposition fluxes by averaging modeled deposition over the watershed region. Geographic shapefiles for the basins were downloaded from Falcone et al.64, except for the shapefile for the Powder River Basin (site ID 06313500), which was available from Falcone et al.65. Statistical significance of the derived WRTDS trends was assessed by calculating the likelihood of increasing or decreasing trends with a bootstrap approach66, using methods available in the R package EGRETci.

Data availability

Simulation data analyzed in this paper are published on ETH Zurich Research Collection (https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000417871). Stream concentrations and discharge are available from the USGS (https://doi.org/10.5066/F7P55KJN).

Code availability

SOCOL-AERv2 code is freely available upon request from the authors, on the condition that users have completed the ECHAM5 license agreement (http://www.mpimet.mpg.de/en/science/models/license/). Analysis of the stream concentration data was conducted using the R package EGRET (https://github.com/USGS-R/EGRET).

References

Mora, C. et al. Broad threat to humanity from cumulative climate hazards intensified by greenhouse gas emissions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 1062–1071 (2018).

Jones, D. L. et al. Nutrient stripping: the global disparity between food security and soil nutrient stocks. J. Appl. Ecol. 50, 851–862 (2013).

Smith, M. R. & Myers, S. S. Impact of anthropogenic CO2 emissions on global human nutrition. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 834–839 (2018).

Galloway, J. N. et al. Transformation of the nitrogen cycle: recent trends, questions, and potential solutions. Science 320, 889–892 (2008).

Haneklaus, S., Bloem, E. & Schnug, E. History of Sulfur Deficiency in Crops. Sulfur: A Missing Link between Soils, Crops, and Nutrition 45–58 https://doi.org/10.2134/agronmonogr50.c4 (2008).

Hinckley, E. L. S., Crawford, J. T., Fakhraei, H. & Driscoll, C. T. A shift in sulfur-cycle manipulation from atmospheric emissions to agricultural additions. Nat. Geosci. 13, 597–604 (2020).

Rayman, M. P. Selenium and human health. Lancet 379, 1256–1268 (2012).

Winkel, L. H. E. et al. Selenium cycling across soil-plant-atmosphere interfaces: a critical review. Nutrients 7, 4199–4239 (2015).

Combs, G. F. Selenium in global food systems. Br. J. Nutr. 85, 517–547 (2001).

Feinberg, A., Stenke, A., Peter, T. & Winkel, L. H. E. Constraining atmospheric selenium emissions using observations, global modeling, and Bayesian inference. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 7146–7155 (2020).

Wen, H. & Carignan, J. Reviews on atmospheric selenium: emissions, speciation and fate. Atmos. Environ. 41, 7151–7165 (2007).

Sheng, J. X. et al. Global atmospheric sulfur budget under volcanically quiescent conditions: aerosol-chemistry-climate model predictions and validation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 256–276 (2015).

Glass, N. R. et al. Effects of acid precipitation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 16, 162A–169A (1982).

Grennfelt, P. et al. Acid rain and air pollution: 50 years of progress in environmental science and policy. Ambio 49, 849–864 (2020).

Peters, G. P. et al. Key indicators to track current progress and future ambition of the Paris Agreement. Nat. Clim. Chang. 7, 118–122 (2017).

Amundson, R. et al. Soil and human security in the 21st century. Science 348, 1261071 (2015).

Jones, G. D. et al. Selenium deficiency risk predicted to increase under future climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 2848–2853 (2017).

Song, T. et al. The origin of soil selenium in a typical agricultural area in Hamatong River Basin, Sanjiang Plain, China. Catena 185, 104355 (2020).

Hinckley, E. L. S. & Matson, P. A. Transformations, transport, and potential unintended consequences of high sulfur inputs to Napa Valley vineyards. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14005–14010 (2011).

Hartmann, K., Lilienthal, H. & Schnug, E. Risk-mapping of potential sulphur deficiency in agriculture under actual and future climate scenarios in Germany. Asp. Appl. Biol. 88, 113–121 (2008).

McGrath, S. P. & Zhao, F. J. A risk assessment of sulphur deficiency in cereals using soil and atmospheric deposition data. Soil Use Manag. 11, 110–114 (1995).

Haygarth, P. M., Cooke, A. I., Jones, K. C., Harrison, A. F. & Johnston, A. E. Long‐term change in the biogeochemical cycling of atmospheric selenium: deposition to plants and soil. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 98, 16769–16776 (1993).

Feinberg, A. et al. Mapping the drivers of uncertainty in atmospheric selenium deposition with global sensitivity analysis. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 1363–1390 (2020).

Feinberg, A. et al. Improved tropospheric and stratospheric sulfur cycle in the aerosol–chemistry–climate model SOCOL-AERv2. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 3863–3887 (2019).

Gidden, M. J. et al. Global emissions pathways under different socioeconomic scenarios for use in CMIP6: a dataset of harmonized emissions trajectories through the end of the century. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 1443–1475 (2019).

Government of Ontario. The end of coal. https://www.ontario.ca/page/end-coal (accessed 20 October 2020).

Smith, S. J. et al. Anthropogenic sulfur dioxide emissions: 1850-2005. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 1101–1116 (2011).

Tian, H. Z. et al. Trend and characteristics of atmospheric emissions of Hg, As, and Se from coal combustion in China, 1980–2007. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 11905–11919 (2010).

Hoesly, R. M. et al. Historical (1750–2014) anthropogenic emissions of reactive gases and aerosols from the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS). Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 369–408 (2018).

Zheng, B. et al. Trends in China’s anthropogenic emissions since 2010 as the consequence of clean air actions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 14095–14111 (2018).

Ramankutty, N., Evan, A. T., Monfreda, C. & Foley, J. A. Farming the planet: 1. Geographic distribution of global agricultural lands in the year 2000. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 22, GB1003 (2008).

White, P. J. & Broadley, M. R. Biofortification of crops with seven mineral elements often lacking in human diets—iron, zinc, copper, calcium, magnesium, selenium and iodine. New Phytol. 182, 49–84 (2009).

Brandt, J. E., Bernhardt, E. S., Dwyer, G. S. & Di Giulio, R. T. Selenium ecotoxicology in freshwater lakes receiving coal combustion residual effluents: a North Carolina example. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 2418–2426 (2017).

Bañuelos, G. S., Lin, Z.-Q. & Broadley, M. Selenium biofortification. in Selenium in Plants (eds Pilon-Smits, E. A. H., Winkel, L. H. E. & Lin, Z.-Q.) 231–255 (Springer, 2017).

Malagoli, M., Schiavon, M., Dall’Acqua, S. & Pilon-Smits, E. A. H. Effects of selenium biofortification on crop nutritional quality. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 280 (2015).

Plant, J. A. et al. Arsenic and selenium. in Treatise on Geochemistry 2nd edn (eds Holland, H. D. & Turekian, K. K.) 13–57 (Elsevier, 2014).

Johnson, R. C. et al. Lifetime chronicles of selenium exposure linked to deformities in an imperiled migratory fish. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 2892–2901 (2020).

Singh, A., Quinn, N. W. T., Benes, S. E. & Cassel, F. Policy-driven sustainable saline drainage disposal and forage production in the Western San Joaquin Valley of California. Sustainability 12, 6362 (2020).

David, M. B., Gentry, L. E. & Mitchell, C. A. Riverine response of sulfate to declining atmospheric sulfur deposition in agricultural watersheds. J. Environ. Qual. 45, 1313–1319 (2016).

Boucher, O. et al. Clouds and aerosols. in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) 571–658 (IPCC AR5, Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Gaffney, J. S. & Marley, N. A. The impacts of combustion emissions on air quality and climate – From coal to biofuels and beyond. Atmos. Environ. 43, 23–36 (2009).

Stenke, A. et al. The SOCOL version 3.0 chemistry–climate model: description, evaluation, and implications from an advanced transport algorithm. Geosci. Model Dev. 6, 1407–1427 (2013).

Egorova, T. A., Rozanov, E. V., Zubov, V. A. & Karol, I. L. Model for investigating ozone trends (MEZON). Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 39, 277–292 (2003).

Roeckner, E. et al. The atmospheric general circulation model ECHAM 5. PART I: Model description. http://www.mpimet.mpg.de/fileadmin/publikationen/Reports/max_scirep_349.pdf (2003).

Weisenstein, D. K. et al. A two-dimensional model of sulfur species and aerosols. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 13019 (1997).

Burkholder, J. B. et al. Chemical kinetics and photochemical data for use in atmospheric studies, evaluation No. 18. https://jpldataeval.jpl.nasa.gov/pdf/JPL_Publication_15-10.pdf (2015).

Kerkweg, A. et al. An implementation of the dry removal processes DRY DEPosition and SEDImentation in the Modular Earth Submodel System (MESSy). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 6, 4617–4632 (2006).

Kerkweg, A. et al. Corrigendum to ‘Technical note: an implementation of the dry removal processes DRY DEPosition and SEDImentation in the Modular Earth Submodel System (MESSy)’. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 9569 (2009).

Tost, H., Jöckel, P., Kerkweg, A., Sander, R. & Lelieveld, J. A new comprehensive SCAVenging submodel for global atmospheric chemistry modelling. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 6, 565–574 (2006).

Lana, A. et al. An updated climatology of surface dimethlysulfide concentrations and emission fluxes in the global ocean. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 25, GB1004 (2011).

Nightingale, P. D. et al. In situ evaluation of air‐sea gas exchange parameterizations using novel conservative and volatile tracers. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 14, 373–387 (2000).

Andres, R. J. & Kasgnoc, A. D. A time‐averaged inventory of subaerial volcanic sulfur emissions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 103, 25251–25261 (1998).

Dentener, F. et al. Emissions of primary aerosol and precursor gases in the years 2000 and 1750 prescribed data-sets for AeroCom. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 6, 4321–4344 (2006).

Sheng, J. et al. Global atmospheric sulfur budget under volcanically quiescent conditions: Aerosol‐chemistry‐climate model predictions and validation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 256–276 (2015).

Sindelarova, K. et al. Global data set of biogenic VOC emissions calculated by the MEGAN model over the last 30 years. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 9317–9341 (2014).

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, 4407 (2003).

Meehl, G. A. et al. Climate change projections in CESM1(CAM5) compared to CCSM4. J. Clim. 26, 6287–6308 (2013).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of IGAC/SPARC chemistry-climate model initiative (CCMI) community simulations in support of upcoming ozone and climate assessments. SPARC Newsletter 40, 48–66 (2013).

Revell, L. E. et al. Drivers of the tropospheric ozone budget throughout the 21st century under the medium-high climate scenario RCP 6.0. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 5887–5902 (2015).

Dee, D. P. et al. The ERA-Interim reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 137, 553–597 (2011).

Hirsch, R. M. & De Cicco, L. A. User guide to Exploration and Graphics for RivEr Trends (EGRET) and dataRetrieval: R packages for hydrologic data. https://doi.org/10.3133/tm4A10 (2015).

Hirsch, R. M., Moyer, D. L. & Archfield, S. A. Weighted regressions on time, discharge, and season (WRTDS), with an application to Chesapeake Bay River inputs1. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 46, 857–880 (2010).

Oelsner, G. P. & Stets, E. G. Recent trends in nutrient and sediment loading to coastal areas of the conterminous U.S.: insights and global context. Sci. Total Environ. 654, 1225–1240 (2019).

Falcone, J. A., Baker, N. T. & Price, C. V. Watershed boundaries for study sites of the U.S. Geological Survey Surface Water Trends project: U.S. Geological Survey data release. https://doi.org/10.5066/F78S4N29 (2017).

Falcone, J. A. GAGES-II: Geospatial Attributes of Gages for Evaluating Streamflow. https://water.usgs.gov/lookup/getspatial?gagesII_Sept2011 (2011).

Hirsch, R. M., Archfield, S. A. & De Cicco, L. A. A bootstrap method for estimating uncertainty of water quality trends. Environ. Model. Softw. 73, 148–166 (2015).

Dinh, Q. T. et al. Bioavailability of selenium in soil-plant system and a regulatory approach. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 443–517 (2019).

Li, Z. et al. Interaction between selenium and soil organic matter and its impact on soil selenium bioavailability: a review. Geoderma 295, 69–79 (2017).

Kovar, J. L. & Grant, C. A. Nutrient cycling in soils: sulfur. in Soil Management: Building a Stable Base for Agriculture (eds Hatfield, J. L. & Sauer, T. J.) 103–115 (American Society of Agronomy and Soil Science Society of America, 2011). https://doi.org/10.2136/2011.soilmanagement.c7

Scherer, H. W. Sulfur in soils. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 172, 326–335 (2009).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Timofei Sukhodolov (PMOD/ETH) for help with setting up future climate simulations. Thanks to Connor Olson (Syracuse University) for assistance with Geographic Information System (GIS) software. We thank all researchers involved in collecting, analyzing, and publishing datasets as part of the European Monitoring and Evaluation Programme, Environment and Climate Change Canada, the USGS National Water Information System database, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs of the UK, and the US Environmental Protection Agency. This project was supported by a grant from ETH Zurich under the project ETH-39 15-2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S., T.P., and L.H.E.W. acquired funding for the project and supervised the work. A.F, A.S., T.P., and L.H.E.W. designed the research and C.T.D. and E.-L.S.H advised the research design for the stream analysis. A.F. performed the analysis and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Primary handling editor: Clare Davis

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Feinberg, A., Stenke, A., Peter, T. et al. Reductions in the deposition of sulfur and selenium to agricultural soils pose risk of future nutrient deficiencies. Commun Earth Environ 2, 101 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00172-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00172-0

This article is cited by

-

Biodegradation and bioavailability of low-molecular-weight dissolved organic sulphur in soil and its role in plant-microbial S cycling

Plant and Soil (2024)

-

Direct and Indirect Linkages Between Trace Element Status and Health Indicators - a Multi-tissue Case-Study of Two Deer Species in Denmark

Biological Trace Element Research (2023)

-

Understanding soil selenium accumulation and bioavailability through size resolved and elemental characterization of soil extracts

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Enhanced mitigation in nutrient surplus driven by multilateral crop trade patterns

Communications Earth & Environment (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.