Abstract

The earliest evidence of life captured in lithified microbial mats (microbialites) predates the onset of oxygen production and yet, modern oxygenic mats are often studied as analogs based on their morphological similarity and their sedimentological and biogeochemical context. Despite their structural similarity to fossil microbialites, the presence of oxygen in most modern microbial mats disqualifies them as appropriate models for understanding early Earth conditions. Here we describe the geochemistry, element cycling and lithification potential of microbial mats that thrive under permanently anoxic conditions in arsenic laden, sulfidic waters feeding Laguna La Brava, a hypersaline lake in the Salar de Atacama of northern Chile. We propose that these anoxygenic, arsenosulfidic, phototrophic mats are a link to the Archean because of their distinctive metabolic adaptations to a reducing environment with extreme conditions of high UV, vast temperature fluctuations, and alkaline water inputs from combined meteoric and volcanic origin, reminiscent of early Earth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although the exact date is not known, it is generally accepted that life appeared in the Precambrian, and most likely in the Archean, when superplume events and formation of large igneous provinces were prevalent1. During the Archean, oceanic conditions were anoxic1,2, ferruginous3, silicic4, and enriched in trace elements including Ni, Co, Au, As, Mn, and Ba5. Early microbial mats were abundant6,7,8,9,10,11,12 and stromatolites, their lithified remains, were biologically formed as early as 3.48-3.70 Ga ago6,13,14,15,16,17,18. This preceded the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) by over one billion years, even though recent geochemical evidence suggests a presence of oxygen earlier than the GOE by a few hundred million years19,20.

Because of the prevailing anoxia, the primary photosynthetic mode to support life in Archean microbial mats must have been initially anoxygenic21,22. Based on evidence from early Archean microbialites, hydrogen, ferrous iron, reduced sulfur, nitrite, or possibly organic molecules were possible electron donors for anoxygenic photosynthesis22. It was not until the discovery of arsenotrophy in modern systems of Mono Basin, California23,24,25 that the use of As(III) for photosynthesis in the Precambrian was proposed as well26.

Studies of shales show a significant increase in As(V) before the rise of atmospheric oxygen27. This accumulation of oxidized arsenic suggests biological activity and more arsenic cycling during the late Archean. Synchrotron studies of samples from the Tumbiana Formation (2.72 Ga) in Western Australia28 provide tantalizing evidence for arsenophototrophy as the photosynthetic mode in Archean microbialites. The stromatolitic structures in these samples show the coinciding spatial distribution of organic carbon and arsenic but not iron or sulfur.

In addition to the oxidation of As(III) to As(V) described above, a reductive pathway from photosynthetically generated As(V) back to As(III) forms a complete arsenic cycle. Arsenate reduction requires a low Eo′ electron donor such as H2 or acetate29, and thus could have evolved on early Earth23. The antiquity of this metabolism is shown by phylogenetic evidence in the deeply rooted Crenarchaeota29.

Microbial arsenic cycling has been investigated extensively in modern systems30,31,32,33,34,35,36. Oxidation of As(III) is either chemolithotrophic using O2 or NO3− as electron acceptor37,38 or phototrophic23. Reduction of As(V) is coupled to organic electron donors and is carried out by sulfate-reducing bacteria39. Alternatively, As(V) reduction can also be coupled to H2S oxidation in a chemolithotrophic reaction24. Until now, a living permanently anoxic microbial mat using both oxidative and reductive pathways in the absence of oxygen (e.g., complete arsenic cycling) has not been reported.

The Salar de Atacama, northern Chile, is an arid high altitude alkaline playa system subject to extreme UV exposure (≤64.3 W m−2), low relative humidity (0.4%), limited meteoric input (1–6 mm y−1) and extensive daily and seasonal temperature fluctuations. In spite of the aridity that may have prevailed for as long 150 million years40, several lakes have formed in the gypsum deposits of the southern Atacama41, including Laguna La Brava (23° 43′ 55″ S, 68° 14′ 49″ W; 2293 masl; Fig. 1). The Laguna La Brava is shallow (<0.7 m), contains <0.13 mM dissolved As, <0.006 mM HS− and has an alkalinity of 685 ± 12 mg CaCO3/L42. During the summer, the evaporation from the lake exceeds water input. Various types of oxygenic microbial mats and microbialites are found near the shoreline of the lake. Carbonate minerals, when present, are only found within the microbialites, not on the surface43.

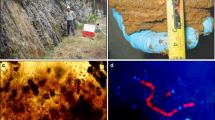

Description of the fieldsite: a Map of Northern Chile; b Detail of frame (a) showing Laguna La Brava in the southern Atacama; paleoshorelines visible to the north; c The channel showing the mats (purple); channel width in foreground is about 3 m; d Hand sample in cross section of studied mat; e Phase-contrast microscopic image showing Ectothiorhodospira-like bacteria from purple layer (see frame, d).

The La Brava mats studied here have not been previously described. They developed in a narrow channel between an alkaline groundwater spring and the lake proper (Fig. 1). A salient feature of these mats is their permanent anoxia. The biogeochemical measurements reported here demonstrate vigorous As and S cycling. These mats also precipitate carbonate minerals, a process potentially enhanced more by arsenic cycling than by sulfur. This modern example of arsenic and sulfur cycling represents a link to Precambrian environments.

Results

Site geochemistry

The La Brava spring is fed continuously by alkaline groundwater leached through calc-alkaline volcanic rock44. The water contains high concentrations of arsenic (0.82–1.51 mM) and sulfide (0.67-1.9 mM), and is low in iron (0.05–0.1 ppb) with a pH of 7.9–8.4 and a carbonate alkalinity of 342 ± 14 mg/L (n = 5). The flow rate of the spring fluctuates between 105 and 185 L s−1. A narrow channel (200 m long, 1–3 m wide, <15 cm deep) connects the spring and Laguna La Brava. Microbial mats cover the bottom of most of the stream (Fig. 1).

Measurements show that the sulfide concentration in the water column at the study site is 60–104 μM and total arsenic seasonally ranges from 180 to 250 μM. The minimum water temperature in the winter is −3.2 °C, and the maximum temperature in the summer is 31.4 °C. The pH ranges from 7.92 to 8.37, the salinity from 60–71 ppt and the water depth over the microbial mat from 30 to 70 mm.

Microscopy

Light microscopy revealed prolific population of the unicellular purple sulfur bacteria (PSB) resembling Ectothiorhodospira sp. (Fig. 1), and occasionally Chloroflexus-like filamentous green-nonsulfur bacteria. Hand samples show the presence of mineral grains (Fig. 2b). When these grains are subjected to the acid test (1 N HCl), rapid CO2 generation is observed consistent with carbonate minerals45.

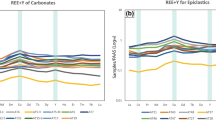

Geochemical and microbial metabolic observations in the channel mats; from left to right: a μXRF (top) and μXANES (bottom) images showing a heat map of As distribution (top) and point measurements indicating the presence of two As oxidation states (bottom; red lines depict As spectra at pt 1 and pt 2; black lines are As(III) and As(V) standards) in the surface of the mat (see white frame, b); b Hand sample in cross section showing the different layers and mineral precipitates in pink layer; dashed line indicates mat surface. Arrow indicates precipitated carbonate mineral. White frame shows location of measurements in (a); c Depth profiles of sulfide (black), pH (red), and oxygen (blue; minute concentration only detected near the surface of the water indicating anoxia in the mat and overlying water) solid lines represent daytime measurements, dashed lines are night-time observations; bold black horizontal line indicates mat-water interface (depth = zero mm; water depth indicated as negative integer); d 2D distribution of sulfate-reducing activity in upper 10 mm of the mat (pixels showing locations of SR; darker pixels indicate higher rates). Measurements were carried out in the Chilean summer of 2015. Please note that b–d have corresponding vertical (depth) scales.

Pigment analyses

The dominant photopigment in the photic zone (upper ~3 mm) was bacteriochlorophyll a (1.07–1.93 mg BChla.cm−3), with traces of BChlc (0–0.09 mg BChlc.cm−3). No chlorophyll a (Chla) was found.

Oxygen, sulfur, and pH distribution with depth

Polarographic microelectrode measurements covering both summer and winter seasons during multiple years (2012–2015) confirmed the permanent absence of O2 in the bottom half of the water column (Fig. 2c). The permanently anoxic nature of the mats was corroborated by needle optode measurements and further supported by sulfide measurements with polarographic and ion-selective Ag–Ag2S needle electrodes. These measurements revealed the presence of free sulfide in the water column and the mat. Measurements taken during the early afternoon showed a characteristic sulfide minimum between 1.25 and 1.75 mm depth in the purple layer of the mat. At night, in the absence of phototrophic oxidation, the concentration of sulfide increased with depth and resulted in a flux from the mat to the overlying water suggesting a source deeper in the mat (Fig. 2c).

Mat manipulations in situ showed that when the solar radiation was completely blocked during peak anoxygenic photosynthesis, an immediate increase of the sulfide concentration occurred in the upper layers (Supplemental Fig. 1). The maximum pH of 9.1 was observed at 2–2.5 mm depth during the early afternoon (Fig. 2c). In contrast, the pH decreased to 7.1 during the early morning. Sulfate reduction maps measured in the early afternoon revealed a relatively homogenous distribution of this respiratory pathway throughout the mat (Fig. 2d).

Arsenic measurements

Dissolved As in the porewater of mat samples was 45 ± 5 μM (n = 6; late summer) and 218 ± 12 μM (n = 3; winter). Elemental distribution maps generated by μXRF and μXANES in thin sections revealed the coexistence of As(III) and As(V) near the surface of the mat (Fig. 2a).

Arsenic and sulfur turnover

The potential of arsenic and sulfur metabolism was investigated by time series experiments. For arsenic, a spike of As(III) was immediately oxidized, and this only occurred in live slurries that were placed in the light or that received nitrate but no light (Fig. 3a). Light-supported As(III) consumption was 10× greater than in the dark incubated nitrate slurries (Fig. 3e, Supplemental Table 1). As(V) reduction was stimulated by addition of acetate and lactate. Little As(V) consumption was found in killed mats or when no electron donor was supplied (Fig. 3b).

Arsenic and sulfur consumption in homogenized La Brava mat samples (slurries). a, b time series of arsenic consumption (As additions at t = 0); a As(III) oxidation in various treatments showing rapid consumption of arsenite in the light and no or little change in other treatments; b As(V) reduction in various treatments, indicating rapid consumption in the presence of added acetate and lactate; c, d time series of sulfur consumption (S additions at t = 0); c Sulfide oxidation in various treatments showing rapid consumption of sulfide in the light, slower consumption with nitrate and no or little change in other treatments; d Sulfate reduction in various treatments, indicating rapid consumption in the presence of added acetate and lactate; all error bars indicate ±1 SD; e Comparison of maximum potential rates by treatment between arsenic (blue; see a, b) and sulfur (orange; see c, d) (see Supplemental Table 1). Pink-shaded rectangle shows oxidation rates, green rectangle indicates reduction rates.

For sulfur, a spike of HS− was consumed instantaneously in the light and faster than in the dark when nitrate was present (Fig. 3c). The reduction of amended sulfate was stimulated by acetate and lactate (Fig. 3d) at rates similar to arsenate (Fig. 3e, Supplemental Table 1). Oxidative and reductive As and S consumption were virtually nonexistent in dark incubations and killed slurry controls.

Metagenomics

Metagenomic analyses revealed the presence of aioA (in α −Proteobacteria (e.g., Rhodobacterales), which include sulfide-oxidizers), arrA (associated with δ- and γ-Proteobacteria, e.g., sulfate-reducing bacteria), and arxA genes (predominantly in Chromatiales, including Thiocapsa and Ectothiorhodospira)46.

Discussion

The closest Archean analog to the La Brava channel system are the lakes of the Tumbiana Formation. These lakes likely comprised diverse microbial habitats several 100 million years before the GOE, some anoxygenic phototrophic28,47, others possibly supporting some level of oxygenic photosynthesis17,47,48,49. These microbial communities lithified extensively28,49,50, and may have cycled S, As, and Fe for energetic purposes17,28.

The Tumbiana Formation extended over 680 km50 and included several lakes17. These lakes were shallow (<2 m49), hypersaline41,47, net evaporitic, and carbonate-rich, with an anoxic water column47,49,51,52, and fluvial input47,49. Surrounded by volcanoes, this largest known Archean series of lakes received direct (through water flowing through alkaline, subaerial basalts) and indirect (through tuff) volcanic inputs47, which resulted in a low iron, high carbonate content and high alkalinity53. The water column and sediments supported sulfur cycling and methanogenesis17,54,55,56,57,58. There was a diversity of microbial mats and stromatolites48,50 that actively precipitated carbonates17, with low-Mg calcite as the main mineral50,59. Although the solar luminosity during the lifetime of the Tumbiana lakes was likely 20% less than present50,60,61, in an atmosphere lacking ozone, the UV levels were expected to be significantly higher than present day sea level measurements57,62,63. These could have been comparable to the UV levels of the high altitude Andean lakes studied here. Temperatures may have fluctuated between 0 and 40 °C63. Most of these geochemical and physicochemical properties are shared by La Brava41,42,64,65,66,67,68,69, and the microbial mats and microbialites it comprises. The composition of the fluvial input to the Tumbiana lakes may also have been similar to the La Brava channel.

Hypersaline alkaline lakes, such as Mono Lake and Searles Lake, CA, contain high concentrations of arsenic (0.2–3 mM). Sediments in these lakes have been shown to exhibit complete arsenic cycling based on separate studies (reviewed in26), however, none were completely independent of either oxygen or nitrate. The La Brava channel mats with a correspondingly high arsenic concentration (~0.2 mM) cycle arsenic under completely anoxic conditions. Atmospheric oxygen is excluded from the mats because it reacts with the sulfide70 that is continuously supplied by upwelled groundwater.

The La Brava channel mats exhibit a purple appearance consistent with PSB (Fig. 1), and a microscopic morphology resembling Ectothiorhodospira sp., with BChla as the major photopigment. The absence of Chla suggests that oxygenic photosynthesis is not supported, which is further confirmed by microelectrode measurements (Fig. 2c). The sulfide minimum in the purple layer and the absence of oxygen demonstrate a sulfidotrophic anoxygenic phototrophic nature of these mats. Arsenic is also present in the porewater and both As(III) and As(V) are found in synchrotron measurements in the photosynthetic layer of the mat, suggesting arsenotrophic photosynthesis could be supported. Future studies using arsenic-specific electrodes could further validate this potential in situ.

Phototrophic oxidation of As(III) by Ectothiorhodospira sp. has been previously demonstrated23,25. The presence of arx genes in our mats was predominantly associated with gammaproteobacteria, which include Ectothiorhodiospira spp. Further gene expression analyses (e.g., metatranscriptomics) could help confirm the role of these organisms.

Experimental observations thus strongly support photosynthesis using both arsenite and sulfide as electron donors as the main oxidative pathways in the channel mats.

In slurries, the potential rate of sulfide consumption in the light was 2.7 times that of arsenite (Fig. 3e; Supplemental Table 1). Arsenite and sulfide were consumed immediately upon addition, suggesting both photosynthetic pathways are constitutively expressed. The turnover rates measured in slurries are typically higher than in intact mats in situ because there is no diffusion limitation and the mat homogenates are preincubated. For example, the phototrophic sulfide oxidation rate estimated from the light–dark shift experiment in situ (39 mM h−1 mg−1 BChla) is slightly lower than the rate in slurries (58 ± 11 mM h−1 mg−1 BChla). Enrichments from photosynthetic biofilms of Paoha, Mono Lake, oxidized As(III) at a rate ranging from 67–100 μM.h−1 (calculated from23), which translates to approximately 0.73 fmol As(III).cell−1.h−1. Using the conversion from BChla to cell number71, ~3.9.108 ml−1 Ectothiorhodospira cells in our slurry experiments oxidize As(III) in the light at a rate of 0.24 fmol As(III) cell−1 h−1.

The reductive part of the arsenic cycle was demonstrated when the mat slurries were amended with As(V) (as arsenate) instead of As (III). Lactate and acetate additions were consumed at similar rates in As(V) and SO42− experiments (Fig. 3e; Supplemental Table 1b). Although the unamended slurries contained sulfide (<0.1 mM), the slow decrease in As(V) in the control suggested slow or absent H2S-supported chemolithotrophic arsenate consumption24 (Fig. 3a, b).

The reduction and oxidation rates of sulfur and arsenic measured in slurries indicate a potential role for both elements in biogeochemical cycling within La Brava channel mats. Validation of the slurry experiment results, especially the similar reduction rates (Fig. 3e and Supplemental Table 1), can be seen by comparison of the bioenergetics of arsenate and sulfate reduction in the oxidation of representative organic matter (CH2O). This shows that their energy yields are similar, with arsenate reduction having a slight energy yield advantage under standard conditions72 but this may deviate under in situ conditions.

The similar potential rates of As(III) and As(V) consumption in La Brava channel mat slurries indicate tight cycling of arsenic, similar to that reported for other elements in microbial mats12. Arsenic cycling potentially enhances carbonate mineral precipitation. It is well established that microbial metabolisms alter pH (Fig. 2c), affecting carbonate mineral precipitation12. For example, balanced chemical equations show that arsenate reduction increases pH and alkalinity:

In contrast, sulfate reduction using these common electron donors decreases pH or has little net effect except in the case of hydrogen73:

This unequivocally demonstrates that arsenate reduction has a greater carbonate mineral precipitation potential than sulfate reduction because of the effect of increased alkalinity on the carbonate mineral saturation index74. Small grains of carbonate minerals are present in the purple layer of the La Brava mat (see abundant white inclusions, Fig. 2b). The precipitation of micritic calcium carbonate is a critical step in the formation and preservation of fine-grained Archean stromatolites in the rock record75, like those present in the Tumbiana Formation13,49,55,56.

Metagenomic analysis provides further evidence of arsenic cycling. The aio system is involved in As(III) oxidation and is widely found among bacteria and archaea. Some PSB (e.g., Ectothiorhodospira sp.76) use the arx system for arsenotrophic phototrophy. In La Brava channel mats, the presence of aio and arx genes combined with the rapid As(III) turnover in slurries, demonstrates the potential of oxidative arsenic conversion. It should be noted that nitrate-supported As(III) oxidation can also rely on the arx system (e.g., in Alkaliminicola sp77), but slower rates in our nitrate amended mat slurries indicated a minor role for this metabolism. This strengthens the link between La Brava mats and Archean microbialite analogs (Supplemental Table 2) because nitrate concentrations in that eon were very low78. The reductive part of the arsenic cycle yielding metabolic energy requires the highly conserved arr genes, which encode for respiration using As(V)29. Arsenate respiration is found in some sulfate-reducing bacteria72 and both sulfide and arsenite oxidation coexist in some PSB25. In mats containing both oxidized and reduced As and S species, this dual mode of respiration may be advantageous. Similarly, a range of arsenic and sulfur cycling genes have been found in microbial mats of Shark Bay, notably associated with sulfate-reducing bacteria79. Complete metagenomic analyses of La Brava mats are published elsewhere45.

The use of reduced sulfur species is prevalent in contemporary mats, including the La Brava channel mats. Prior to 1.8 Ga their use may have been limited by low H2S bioavailability that was insufficient to support extensive sulfidotrophic oxidation80, although a cryptic sulfur cycle was suggested for some of the Tumbiana lakes17,58. The use of H2 by photolithotrophs rather than chemolithotrophs could be excluded based on energetic and ecophysiological principles81,82,83. Ferrophototrophy was used to explain Fe isotopic composition in the highly metamosphosed Isua Supracrustal belt of Greenland84, but the absence of Fe(III) minerals in the Barberton Formation of South Africa did not support the widespread existence of this pathway during the Archean85. Several studies showed that iron-rich carbonates and oxides can form abiotically by reaction between ferric iron and organic carbon during metamorphism86. Fe(III) minerals are also absent in the Tumbiana Formation, indicating a minimal role for Fe(II) as photosynthetic electron donor28. Furthermore, under Archean conditions, sulfide and arsenite were preferable to Fe2+ based on midpoint electron potentials87.

The reduced conditions characteristic of the Archean era leave few possibilities for element cycles due to severe shortage of oxidizing agents, and consequently, early ecosystems were electron donor limited83. Because of the chalcophilic nature of arsenic and the widespread volcanic and geothermal activity inherent to the Archean Earth, major inputs of electron donors were from hydrothermal sources and included Fe(II), H2, As(III), and possibly S (Fig. 4)83,88,89. In deep time, the lack of Fe(III) minerals in fossil shallow coastal mats indicates a major sink for Fe(II) and S in pyrite, and diminished importance of photoferrotrophy relative to photosynthesis using other electron donors. Another possible electron donor is H28; however, competition for H2 from methanogens may have limited its availability within a mat17,83. Considering these limitations on Fe(II) and H2 availability, an alternative electron donor present in relative abundance would have been As(III), which had a pronounced hydrothermal flux89 during the Precambrian26,29. The As(III) availability for mat dwelling phototrophs in the Archean was also enhanced by preferential scavenging of Fe(II) over As(III) by S2-. However, it is plausible that As(III), H2, Fe(II), and perhaps some reduced sulfur were used at the same time. Contemporary PSB are known to use all of these reduced species for photosynthesis22,23,85.

Conceptual model of arsenic and sulfur cycling in the Archean based on observations of contemporary mats in the La Brava channel. The aqueous environment of the La Brava channel mats is permanently anoxic, replicating Archean conditions more closely than other modern mineral-forming mat systems. These mats support vigorous arsenic and sulfur cycling coupled to carbon fixation (anoxygenic photosynthesis) and reoxidation of organic C (anaerobic respiration). The La Brava channel is replete with reduced species (including As(III) and reduced sulfur) and mimics the vast hydrothermal delivery in the Archean. These reduced species are potential electron donors for anoxygenic photosynthesis, which we demonstrate for the La Brava mats and propose for Archean microbial mats. Precipitation of carbonate minerals may be enhanced by the effect of microbial metabolisms (especially arsenate reduction) on alkalinity and saturation indices (which were considerably higher in the Archean).

Although the δ13C value of organic matter in Tumbiana stromatolites could be attributed to CO2 fixation by oxygenic photosynthesis using the Calvin–Benson pathway, anoxygenic photosynthesis could not be ruled out47 because in PSB it also uses the Calvin cycle72. Furthermore, As cycling in the cm-wide domal (i.e., not tufted48) Tumbiana stromatolites is intimately linked with that of sulfur17,58. This As and S link has been shown in contemporary PSB isolated from Mono Lake, CA, and Big Soda Lake, NV, where arsenite-supported phototrophy occurred only in the presence of sulfide25.

An opportunistic use of multiple, scarce electron acceptors in the Archean must have been ecologically advantageous and was facilitated by the non-specific nature of the responsible dimethylsulfoxide reductase, a ubiquitous enzyme family which is common in many sulfate and arsenate respiring microbes90. Indeed, the bioenergetic enzymes arsenite oxidase and arsenate reductase originated in the Archean29. In an environment where the existence of life was challenged by a lack of electron donors and acceptors, robust arsenic cycling could have supported extensive development of microbial mats and microbialites and an exponential increase in Archean global primary production83.

Synchrotron studies of mat samples from the living La Brava channel mats showed the presence of both As(III) and As(V) in the actively metabolizing layer of the mat (Fig. 2a). This further supports the presence of active arsenic cycling in the mat and provides a conceptual link to certain Tumbiana stromatolites described in Sforna et al.28 (Fig. 4).

Here we demonstrate that in the permanently anoxic mats in the Atacama Desert, arsenic and sulfur cycling can sustain high microbial metabolic rates. In these mats, arsenate reduction is energetically preferred over sulfate reduction and has a greater potential to precipitate carbonates. This makes the La Brava mats excellent analogs for the Tumbiana stromatolites (Supplemental Table 2) and potential model systems for understanding Archean life (Fig. 4).

Methods

Site geochemistry

Sampling campaigns were undertaken during the Chilean summers of 2012, 2014, 2015, 2017, and the winter of 2015. Physicochemical measurements (i.e., pH, conductivity, light regime (UVAB, PAR), temperature) were taken repetitively in situ as described before41,42,91,92. The flow rate of the spring was determined using the cross-sectional method93. Water samples were collected on site in acid-washed bottles, filtered, and kept on ice in the dark until further processing (elemental composition, alkalinity titrations41,42,91,92). Mat samples for microscopy, slurry experiments, photopigment measurements, and molecular analysis were stored in gas-tight containers, kept either on ice or with dry ice, and transported to the lab.

Microscopy

The pink mat layer was dissected and viewed using a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 inverted microscope under phase contrast at 400× (LD Plan-neofluar 40×/0.75 Ph). Images were captured with an Axiocam ICm 1 camera and Zeiss Zen Pro 2.3 imaging software.

Pigment analyses

Photopigments were measured in the upper 10 mm of the mats by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; see41 for details) using a Waters 510 system with an online diode array detector (250–800 nm; Waters model 996;). Pigments were identified by comparing the peak retention times and the corresponding absorption spectra against standards available in the laboratory or, when not available, against data in the LipidBank database (http://www.lipidbank.jp). Chla and accessory cyanobacterial pigments (phycobilin, phycoerythrin) could not be detected.

Chla, BChla, and BChlc concentrations were also determined spectrophotometrically94. Mat samples were frozen and three individual layers separated (surface orange, pink middle and bottom tan laminae; Fig. 2b). Additionally, subsamples from the slurry experiments were frozen and kept at −20 °C overnight. Photopigments were extracted from the samples in cold methanol in the dark for 3 h. After centrifugation (5 min at 5000 × g), the absorption in the supernatant was measured on a Varian Cary 50 Probe spectrophotometer at 665 and 770 nm. BChla and BChlc concentrations were calculated using the specific absorption coefficient94. Chla was also not detected by this method.

Oxygen, sulfur, and pH distribution with depth

Depth profiles of pH, sulfide, and oxygen were measured in situ as described before41,42,95,96. Measurements were taken either at 2-h intervals during an entire diel cycle or during peak photosynthesis (12:30–14:00; PAR was 1945–2584 μE m−2 s−1, and UVAB varied from 59.0 to 64.3 W m−2; range for all campaigns) and the end of the night (5:00–6:30). For the light–dark shift, which records phototrophic activity and respiration97,98 (Supplemental Fig. 1), the sulfide profile was measured during peak photosynthesis, as above and then the mat was covered with a black 15 × 15 cm PVC plate with a 2 mm hole in the center for sulfide electrode insertion. Successive sulfide profiles were then measured after 15, 60, 90 (light–dark), 120, 180, and 240 min (dark–light). All profiles were measured using needle-encased glass electrodes to prevent breakage in the lithifying mats and a PA-2000 picoammeter (Unisense, Aarhus, Denmark). The complete absence of oxygen was confirmed with a needle optode, specially constructed by Unisense for use with the Field Microsensor Multimeter.

Arsenic measurements

Samples for As analyses were fixed in the field with EDTA according to Bednar et al.99 and analyzed within a week using Hydride Generation Atomic Fluorescence Spectroscopy (HGAFS; PS Analytical PSA 10.055 Millennium Excalibur, Orpington, Kent, England) according to manufacturer’s specifications.

Upon return to the laboratory, microbial mat samples were step-wise dehydrated with ethanol and impregnated with hard grade LR-white resin according to previously published protocols43,100. Thin sections (~100 μm thick) were scanned in a focused X-ray beam at the ID16b beamline of the ESRF28 with 0.5 µm step size. The 2D element maps were measured at 12.5 keV energy, just above the As K-edge and below the Pb-L3 edge. This made unambiguous detection of As possible. XANES spectra were collected by scanning the energy using 0.5 eV steps around the K-edge of As in X-ray fluorescence and transmission modes. The beam energy was calibrated by defining the edge position of the Legrandite (Zn2(AsO4)(OH)·(H2O)) mineral and As2O5 standards at 11.8745 keV.

Arsenic and sulfur turnover

Mat slabs (10 × 10 cm) were triple-bagged in high-density polyethylene and transported in air-tight containers to the lab, where slurries were prepared and turnover rates determined as described previously92,97,101. Briefly, slurries were prepared from the upper 10 mm of the mat, which represented the active part based on biogeochemical measurements (Fig. 2) and included the ~2.5-mm-thick photosynthetic purple layer. Slurries were obtained by homogenizing with equal volumes of mat and filter-sterilized site water, preincubated while gently stirring in an anaerobic tent (Coy) for 36–72 h under N2 atmosphere, dispensed in 37-ml aliquots, and incubated at room temperature under different experimental conditions (Fig. 3a–d, and Supplemental Table 1). For oxidation experiments: 250 μM addition of As(III) from NaAsO2 stock solution and 600 μM sulfide from Na2S·7–9H2O stock solution; treatments: autoclaved (30 min), live (no additions), nitrate (dark), or light (450 μE m−2 s−1 incandescent light source). For reduction experiments: 500 μM As(V) from a KH2AsO4 stock solution and 500 μM sulfate from Na2SO4 stock solution: autoclaved (30 min), live, acetate, and lactate (10 mM final concentration). Replicate samples were removed at 0.5–1 h intervals, filtered (0.22 μm), and analyzed for As or S species. As(III) and As(V) were measured using HGAFS as described above. Sulfide was measured with an ion-specific sulfide microelectrode (see above) and sulfate was analyzed using ion chromatography with suppressor (Dionex IC-300092). Slurry experiments were carried out twice (summer 2015 and 2017). In order to compare the two experiments, rates were calculated and normalized to the amount of bacteriochlorophyll present in the slurry.

Metagenomics

Samples were taken ~20 cm from the location of microelectrode measurements using a cut off sterile 10-ml syringe. The samples were fixed immediately in RNAlater and transported to the laboratory on ice for further processing as described previously42,46,102. Briefly, replicate DNA extractions (using the Power Biofilm DNA Isolation Kit, MO BIO Laboratories, Inc.) were pooled, sequenced, and sheared to a fragment size of ~400 bp. An amplified library was created using the Illumina TruSeq DNA kit 2 × 300 bp as per the manufacturer’s instructions and mutiplex-sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 1500 platform. Raw data are available from the European Nucleotide Archive under accession number PRJEB2559946. This database contains data from two Atacama lakes, Tebenquiche and La Brava (see41). The La Brava samples used in this study have SRA accession numbers ERR2407577–ERR2407578 both corresponding to the same channel mat sample. Assembled contigs >1000 bp were annotated, binned, and arsenic-related genes were selected for further analysis102. A full description of the metagenomic analysis is published elsewhere46.

Data availability

Raw metagenomics data are available from the European Nucleotide Archive under accession number PRJEB2559946. The La Brava samples used in this study have SRA accession numbers ERR2407577-ERR2407578. All other data underlying the figures in this manuscript are publicly available from the PANGEA repository (PDI-25269).

References

Lyons, T. W., Reinhard, C. T. & Planavsky, N. J. The rise of oxygen in Earth’s early ocean and atmosphere. Nature 506, 307–315 (2014).

Canfield, D. E. The early history of atmospheric oxygen: homage to Robert M. Garrels. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 33, 1–36 (2005).

Poulton, S. & Canfield, D. E. Ferruginous conditions: a dominant feature of the ocean through Earth’s history. Elements 7, 107–112 (2011).

Siever, R. The silica cycle in the Precambrian. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 56, 3265–3272 (1992).

Large, R. R. et al. Trace element content of sedimentary pyrite as a new proxy for deep-time ocean–atmosphere evolution. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 389, 209–220 (2014).

Walter, M. R., Buick, R. & Dunlop, J. S. R. Stromatolites: 3,400–3,500 m year-old from the North Pole area, Western Australia. Nature 284, 443–445 (1980).

Nisbet, E. G. & Fowler, C. M. R. Archean metabolic evolution of microbial mats. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 266, 2375–2382 (1991).

Tice, M. M. & Lowe, D. R. Hydrogen-based carbon fixation in the earliest known photosynthetic organisms. Geology 34, 37 (2006).

Van Kranendonk, M. J. Volcanic degassing, hydrothermal circulation and the flourishing of early life on Earth: new evidence from the Warrawoona Group. Earth-Sci. Rev. 74, 197–240 (2006).

Noffke, N., Eriksson, K. A., Hazen, R. M. & Simpson, E. L. A new window into Early Archean life: microbial mats in Earth’s oldest siliciclastic tidal deposits (3.2 Ga Moodies Group, South Africa). Geology 34, 253 (2006).

Noffke, N., Christian, D., Wacey, D. & Hazen, R. M. Microbially induced sedimentary structures recording an ancient ecosystem in the ca. 3.48 billion-year-old Dresser Formation, Pilbara, Western Australia. Astrobiology 13, 1103–1124 (2013).

Dupraz, C. et al. Processes of carbonate precipitation in modern microbial mats. Earth Sci. Rev. 96, 141–162 (2009).

Sakurai, R., Ito, M., Ueno, Y., Kitajima, K. & Maruyama, S. Facies architecture and sequence-stratigraphic features of the Tumbiana Formation in the Pilbara Craton, northwestern Australia: implications for depositional environments of oxygenic stromatolites during the Late Archean. Precambrian Res. 138, 255–273 (2005).

Allwood, A. C., Walter, M. R., Kamber, B. S., Marshall, C. P. & Burch, I. W. Stromatolite reef from the Early Archaean era of Australia. Nature 441, 714–718 (2006).

Allwood, A. C., Rosing, M. T., Flannery, D., Hurowitz, J. & Heirwegh, C. M. Reassessing evidence of life in 3,700-million-year-old rocks of Greenland. Nature 563, 241–244 (2018).

Nutman, A. P., Bennett, V. C., Friend, C. R. L., Van Kranendonk, M. J. & Chivas., A. R. Rapid emergence of life shown by discovery of 3,700-million-year-old microbial structures. Nature 537, 535–538 (2016).

Lepot, K. et al. Extreme 13C-depletions and organic sulfur argue for S-fueled anaerobic methane oxidation in 2.72 Ga old stromatolites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 244, 522–547 (2019).

Baumgartner, R. et al. Nano-porous pyrite and organic matter in 3.5 billion-year-old stromatolites record primordial life. Geology 47, 1039–1043 (2019).

Planavsky, N. J. et al. Evidence for oxygenic photosynthesis half a billion years before the great oxidation event. Nat. Geosci. 7, 283–286 (2014).

Lalonde, S. V. & Konhauser, K. O. Benthic perspective on Earth’s oldest evidence for oxygenic photosynthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 995–1000 (2015).

Bosak, T., Green, S. E. & Newman, D. K. A likely role for anoxygenic photosynthetic microbes in the formation of ancient stromatolites. Geobiology 5, 119–126 (2007).

Fischer, W. W., Hemp, J. & Johnson, J. E. Evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 44, 647–683 (2016).

Kulp, T. R. et al. Arsenic(III) fuels anoxygenic photosynthesis in hot spring biofilms from Mono Lake, California. Science 321, 967–970 (2008).

Hoeft, S. E., Kulp, T. R., Han, S. Lanoil, B. & Oremland, R. S. Coupled arsenotrophy in a hot spring photosynthetic biofilm at Mono Lake, California. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 4633–4639 (2010).

McCann, S. H. et al. Arsenite as an electron donor for anoxygenic photosynthesis: description of three strains of Ectothiorhodospira from Mono Lake, California and Big Soda Lake, Nevada. Life 7, 1, https://doi.org/10.3390/life7010001 (2017).

Oremland, R. S., Saltikov, C. W., Wolfe-Simon, F. & Stolz, J. F. Arsenic in the evolution of earth and extraterrestrial ecosystems. Geomicrobiol. J. 26, 522–536 (2009).

Fru, E. C. et al. The rise of oxygen-driven arsenic cycling at ca. 2.48 Ga. Geology 47, 243–246 (2019).

Sforna, M. C. et al. Evidence for arsenic metabolism and cycling by microorganisms 2.7 billion years ago. Nat. Geosci. 7, 811–815 (2014).

Van Lis, R., Nitschke, W., Duval, S. & Schoepp-Cothenet, B. Arsenics as bioenergetic substrates. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1827, 176–188 (2013).

Oremland, R. S. & Stolz, J. F. Arsenic, microbes and contaminated aquifers. Trends Microbiol. 13, 45–49 (2005).

Oremland, R. S. et al. A microbial arsenic cycle in a salt-saturated extreme environment. Science 308, 1305–1308 (2005).

Zhu, X. et al. Secondary minerals of weathered orpiment–realgar- bearing tailings in Shimen carbonate-type realgar mine, Changde, Central China. Mineral. Petrol. 109, 1–15 (2013).

Amend, J., Saltikov, C., Lu, G.-S. & Hernandez, J. Microbial arsenic metabolism and reaction energetics. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 79, 391–433 (2014).

Oremland, R. S., Saltikov, C. W., Stolz, J. F. & Hollibaugh, J. T. Autotrophic microbial arsenotrophy in arsenic-rich soda lakes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 364, fnx146, https://doi.org/10.1093/femsle/fnx146 (2017).

Saunders, J. K., Fuchsman, C. A., McKay, C. & Rocap, G. Complete arsenic-based respiratory cycle in the marine microbial communities of pelagic oxygen-deficient zones. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 9925–9930 (2019).

Hu, S.-Y. et al. Life on the edge: microbial biomineralization in an arsenic- and lead-rich deep-sea hydrothermal vent. Chem. Geol. 533, 119438 (2020).

Ilyaletdinov, A. N. & Abdrashitova, S. A. Autotrophic oxidation of arsenic by a culture of Pseudomonas arsenioxidans. Mikrobiologiya 50, 135–140 (1981).

Oremland, R. S. et al. Anaerobic oxidation of arsenite in Mono Lake water and by a facultative chemoautotroph, strain MLHE-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 4795–4802 (2002).

Newman, D. K., Ahmann, D. & Morel, F. M. M. A brief review of microbial arsenate respiration. Geomicrobiol. J. 15, 255–268 (1998).

Hartley, A. J., Chong, G., Houston, J. & Mather, A. E. 50 million years of climatic stability: evidence from the Atacama Desert, northern Chile. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 162, 421–424 (2005).

Farias, M. E. et al. Characterization of bacterial diversity associated with microbial mats, gypsum evaporites, and carbonate microbialites in thalassic wetlands: Tebenquiche and Brava, Salar de Atacama, Chile. Extremophiles 18, 311–329 (2014).

Farias, M. E. et al. Prokaryotic diversity and biogeochemical characteristics of benthic microbial ecosystems at La Brava, a hypersaline lake at Salar de Atacama, Chile. PLoS ONE 2, e0186867 (2017).

Sancho-Tomás, M. et al. Distribution, redox and (bio)geochemical implications of arsenic in living microbial mats of Laguna Brava, Salar de Atacama. Chem. Geol. 490, 13–21 (2018).

Deruelle, B. Petrology of the plio-quaternary volcanism of the South-Central and Meridional Andes. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 14, 77–124 (1982).

Green, O. Field staining techniques for determining calcite, dolomite and phosphate. In A Manual of Practical Laboratory and Field Techniques in Palaeobiology. 55–58 (Springer, Dordrecht, 2001).

Saona, L. A. et al. Analysis of co-regulated abundance of genes associated with arsenic and phosphate metabolism in Andean Microbial Ecosystems. https://doi.org/10.1101/870428 (2019).

Stüeken, E. E. et al. Environmental niches and metabolic diversity in Neoarchean lakes. Geobiology 15, 767–783 (2017).

Flannery, D. T. & Walter, M. R. Archean tufted microbial mats and the Great Oxidation Event: new insights into an ancient problem. Austral. J. Earth Sci. 59, 1–11 (2012).

Coffey, J. M., Flannery, D. T., Walter, M. R. & George, S. C. Sedimentology, stratigraphy and geochemistry of a stromatolite biofacies in the 2.72 Ga Tumbiana Formation, Fortescue Group, Western Australia. Precam. Res. 236, 282–296 (2013).

Awramik, S. M. & Buchheim, H. P. A giant, Late Archean lake system: the Mentheena Member (Tumbiana Formation; Fortescue Group), Western Australia. Precambrian Res. 174, 215–240 (2009).

Van Kranendonk, M. J., Webb, G. E. & Kamber, B. S. Geological and trace element evidence for a marine sedimentary environment of deposition and biogenicity of 3.45 Ga stromatolitic carbonates in the Pilbara Craton, and support for a reducing Archaean ocean. Geobiology 1, 91–108 (2003).

Bolhar, R. & van Kranendonk, M. J. A non-marine depositional setting, for the northern Fortescue Group, Pilbara Craton, inferred from trace element geochemistry of stromatolitic carbonates. Precambrian Res. 155, 229–250 (2007).

Stüeken, E. E., Buick, R. & Schauer, A. Nitrogen isotope evidence for alkaline lakes on late Archean continents. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 411, 1–10 (2015).

Hinrichs, K. Microbial fixation of methane carbon at 2.7 Ga; was an anaerobic mechanism possible? Geochem. Geophys. 3, 1–10 (2002).

Lepot, K., Benzerara, K., Brown, G. E. Jr & Philippot, P. (2008) Microbially influenced formation of 2,724-million-year-old stromatolites. Nat. Geosci. 1, 118–121 (2008).

Lepot, K. et al. Organic matter heterogeneities in 2.72 Ga stromatolites: Alteration versus preservation by sulfur incorporation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 6579–6599 (2009).

Stüeken, E. E., Catling, D. C. & Buick, R. Archean sulphur cycling by life on land. Nat. Geosci. 5, 722–725 (2012).

Marin-Carbonne, J. et al. Sulfur isotope’s signal of nanopyrites enclosed in 2.7 Ga stromatolitic organic remains reveal microbial sulfate reduction. Geobiolology 16, 121–138 (2017).

Buick, R. The antiquity of oxygenic photosynthesis: evidence from stromatolites in sulphate-deficient Archaean lakes. Science 255, 74–77 (1992).

Pavlov, A. A., Brown, L. L. & Kasting, J. F. UV shielding of NH3 and O2 by organic hazes in the Archean atmosphere. J. Geophys. Res. 106, 267–288 (2001).

Claire, M. W. et al. The evolution of solar flux from 0.1 nm to 160 μm: quantitative estimates for planetary studies. Astrophys. J. 757, 95. (12pp). (2012).

Cockell, C. S. & Raven, J. A. Ozone and life on the Archean Earth. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 365, 1889–1901 (2007).

Catling, D. C. & Zahnle, K. J. The Archean atmosphere. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax1420 (2020).

Risacher, F., Alonso, H. & Salazar, C. The origin of brines and salts in Chilean salars: a hydrochemical review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 63, 249–293 (2003).

Arrigada, C., Roperch, P., Mpodozis, C. & Fernandez, R. Paleomagnetism and tectonics of the southern Atacama Desert (25–28° S), northern Chile. Tectonics 25, TC4001 (2006).

Fernandez, A. B. et al. Microbial diversity in sediment ecosystems (evaporites, domes, microbial mats, and crusts) of hypersaline Laguna Tebenquiche, Salar de Atacama, Chile. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1284 (2016).

Corenthal, L. G., Boutt, D. F., Hynek, S. A. & Munk, L. A. Regional groundwater flow and accumulation of a massive evaporite deposit at the margin of the Chilean Altiplano. J. Geophys. Res. 43, 8017–8025 (2016).

Tapia, J. et al. Geology and geochemistry of the Atacama Desert. Ant. Leeuw. 111, 1273–1291 (2018).

Rasuk, M. C., P. T. Visscher, M. Contreras, M. E. Farias. Mats and microbialites from Laguna La Brava. In Extremophile microbial ecosystems in Central Andes Extreme Environments: Biofilms Microbial, Mats, Microbialites and Endoevaporites. (ed. Farias, M. E.) (Springer Verlag, 2020) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36192-1.

Millero, F. J. The thermodynamics and kinetics of the hydrogen sulfide in natural waters. Mar. Chem. 18, 121–147 (1986).

Kondratieva, E. N., Zhukov, V. G., Ivanovsky, R. N., Petushkova, Y. P. & Monosov, E. Z. The capacity of the phototrophic sulfur bacterium Thiocapsa roseopersicina for chemosynthesis. Arch. Microbiol. 108, 287–292 (1976).

Megonigal, J. P., Hines, M. E. & Visscher, P. T. Anaerobic metabolism and production of trace gases. In Treatise on Geochemistry, Vol. 8. (eds Holland, H.D. & Turekian, K. K.) 317–424 (Elsevier, The Netherlands, 2003).

Gallagher, K. L., Kading, T. J., Braissant, O., Dupraz, C. & Visscher, P. T. Inside the alkalinity engine: the role of electron donors in the organomineralization potential of sulfate reducing bacteria. Geobiology 10, 518–530 (2012).

Stumm, W. & Morgan, J. J. Chemical equilibria and rates in natural waters. 3rd edn. 1040 (John Wiley, New York, 1995).

Franz, C. M., Petryshyn, V. A. & Corsetti, F. A. Grain trapping by filamentous cyanobacterial and algal mats: implications for stromatolite microfabrics through time. Geobiology 13, 409–423 (2015).

McCann, S. H. et al. Arsenite as an electron donor for anoxygenic photosynthesis: description of three strains of Ectothiorhodospira from Mono Lake, California and Big Soda Lake, Nevada. Life 7, 1, https://doi.org/10.3390/life7010001 (2016).

Hoeft, S. E. et al. Alkalilimnicola ehrlichii sp. nov., a novel, arsenite- oxidizing haloalkaliphilic gammaproteobacterium capable of chemoautotrophic or heterotrophic growth with nitrate or oxygen as the electron acceptor. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57, 504–512 (2007).

Zerkle, A. L. & Mikhail, S. The geobiological nitrogen cycle: from microbes to the mantle. Geobiology 15, 343–352 (2017).

Wong, H. L. et al. Disentangling the drivers of functional complexity at the metagenomic level in Shark Bay microbial mat microbiomes. ISME J. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-018-0208-8 (2018).

Poulton, S. W., Fralick, P. W. & Canfield, D. E. The transition to a sulphidic ocean ~1.84 billion years ago. Nature 431, 173–177 (2004).

Kral, T. A., Brink, K. M., Miller, S. L. & McKay, C. P. Hydrogen consumption by methanogens on the early Earth. Org. Life Evol. Biosph. 28, 311–319 (1998).

Vignais, P. M. & Biloud, B. Occurrence, classification and biological function of hydrogenases: an overview. Chem. Rev. 107, 4206–4272 (2007).

Ward, L. M., Rasmussen, B. & Fischer, W. W. Primary productivity was limited by electron donors prior to the advent of oxygenic photosynthesis. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 124, 211–226 (2019).

Czaja, A. D. et al. Biological Fe oxidation controlled deposition of banded iron formation in the ca. 3770 Ma Isua Supracrustal Belt (West Greenland). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 363, 192–203 (2013).

Tice, M. M. & Lowe, D. R. Photosynthetic microbial mats in the 3,416-Myr-old ocean. Nature 431, 549–552 (2004).

Halama, M., Swanner, E. D., Konhauser, K. O. & Kappler, A. Evaluation of siderite and magnetite formation in BIFs by pressure-temperature experiments of Fe(III) minerals and microbial biomass. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 450, 243–253 (2016).

Martin, W. F., Bryant, D. A. & Beatty, J. T. A physiological perspective on the origin and evolution of photosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 42, 205–231 (2018).

Duda, J. P. et al. A rare glimpse of paleoarchean life: geobiology of an exceptionally preserved microbial mat facies from the 3.4 Ga Strelley Pool Formation, Western Australia. PLoS ONE 11, e0147629 (2016).

Fru, C. et al. Arsenic stress after Proterozoic glaciations. Sci. Rep. 5, 17789 (2015).

Miralles-Robledillo, J. M., Torregrosa, J., Martinez-Espinosa, R. M. & Pire, C. DMSO reductase family: phylogenetics and applications of extremophiles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20133349 (2019).

Dupraz, C., Fowler, A., Tobias, C. & Visscher, P. T. Stromatolitic knobs in Storr’s Lake (San Salvador, Bahamas): a model system for formation and alteration of laminae. Geobiology 11, 527–548 (2013).

Pace, A. et al. Formation of stromatolite lamina at the interface of oxygenic-anoxygenic photosynthesis. Geobiology 16, 378–398 (2018).

Mitchell, M. K. & Stapp, W. Field manual for water quality monitoring. 5th edn. (Thomson Shore Printers, Dexter, MI, 1986).

Stal, L. J., van Gemerden, H. & Krumbein, W. E. The simultaneous assay of chlorophyll and bacteriochlorophyll in natural microbial communities. J. Microbiol. Methods 2, 295–306 (1984).

Visscher, P. T., Beukema, J. & van Gemerden, H. In situ characterization of sediments: Measurements of oxygen and sulfide profiles with a novel combined needle electrode. Limnol. Oceanogr. 36, 1476–1480 (1991).

Pagès, A. et al. Diel fluctuations in solute distributions and biogeochemical cycling in a hypersaline microbial mat from Shark Bay, WA. Mar. Chem. 167, 102–112 (2014).

Visscher, P. T. et al. Formation of lithified micritic laminae in modern marine stromatolites (Bahamas): the role of sulfur cycling. Am. Mineral. 83, 1482–1494 (1998).

Epping, H. G., Khalili, A. & Thar, R. Photosynthesis and the dynamics of oxygen consumption in a microbial mat as calculated from transient oxygen microprofiles. Limnol. Oceanogr. 44, 1936–1948 (1999).

Bednar, A. J., Garbino, J. R., Ranville, J. F. & Wildeman, T. R. Preserving the distribution of inorganic arsenic species in groundwater and acid mine drainage samples. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36, 2213–2218 (2002).

Somogyi, A. et al. Optical design and multi-length-scale scanning spectro-microscopy possibilities at the Nanoscopium beamline of synchrotron Soleil. J. Synchrotron. Radiat. 22, 1118–1129 (2015).

Visscher, P. T. et al. Dimethyl sulfide and methanethiol formation in microbial mats: Potential pathways for biogenic signatures. Environ. Microbiol. 5, 296–308 (2003).

Kurth, D. et al. Arsenic metabolism in high altitude modern stromatolites revealed by metagenomic analysis. Sci. Rep. 7, 1024 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from NSF grant OCE 1561173 (US) to P.T.V. and ISITE project UB18016-BGS-IS (France) to P.T.V., E.V., A.B., and the São Paulo Research Foundation FAPESP, grant 2015/16235-2 (Brazil) to P.P.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.T.V., M.R.W., and P.P. discussed Archean microbialite biogeochemistry. P.T.V. discovered the anoxic mats, conceived the study, performed the fieldwork (with P.P. and M.E.F.), laboratory experiments, bulk of the analyses, and synthesized the data with K.L.G., P.T.V. and K.L.G. wrote the paper with input from C.D., P.P., M.R.W., R.B., and E.V. M.S.-T., A.S., K.M., and A.B. carried out synchrotron-based analyses, M.E.F., D.K., and B.P.B. performed molecular analyses, M.E.F. and M.C. introduced P.T.V. to the La Brava field site and provided logistic support for field and lab work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Primary handling editor: Joe Aslin

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Visscher, P.T., Gallagher, K.L., Bouton, A. et al. Modern arsenotrophic microbial mats provide an analogue for life in the anoxic Archean. Commun Earth Environ 1, 24 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-020-00025-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-020-00025-2

This article is cited by

-

Dissecting Light Sensing and Metabolic Pathways on the Millimeter Scale in High-Altitude Modern Stromatolites

Microbial Ecology (2023)

-

Lithifying and Non-Lithifying Microbial Ecosystems in the Wetlands and Salt Flats of the Central Andes

Microbial Ecology (2022)

-

Phosphate-Arsenic Interactions in Halophilic Microorganisms of the Microbial Mat from Laguna Tebenquiche: from the Microenvironment to the Genomes

Microbial Ecology (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.