Abstract

Ramsey interferometers using internal electronic or nuclear states find wide applications in science and engineering. We develop a matter wave Ramsey interferometer for trapped motional quantum states exploiting the s- and d-bands of an optical lattice and study it both experimentally and theoretically, identifying the different de-phasing and de-coherence mechanisms. Implementing a band echo technique, employing repeated π-pulses we suppress the de-phasing evolution and significantly increase the coherence time of the trapped state interferometer by one order of magnitude. Thermal fluctuations are the main mechanism for the remaining decay of the contrast. Our demonstration of an echo-Ramsey interferometer with trapped quantum states in an optical lattice has potential application in the study of quantum many-body lattice dynamics, and motional qubits manipulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Interferometers employing separated oscillating fields to create and probe superpositions of states, also known as Ramsey interferometry (RI), have originaly been developed for magnetic resonance to measure transition frequencies1,2 and were then extended to a general tool of spectrocopy and matter wave interferometry3,4,5. Typical sequences consist of two π/2 pulses separated by an time for free evolution or a π/2 − π − π/2 sequence. Ramsey interferometers using internal electronic or nuclear states already have played an important role in accurate quantum state engineering and quantum metrology, such as in nuclear magnetic resonance6, atomic clocks7, quantum information8 and quantum simulation9. In general, echo techniques are used in RIs to suppress de-phasing for significantly increasing the coherent time10,11,12. Even though motional states of particles are on the same footing as internal states in current quantum technologies, i.e., motional qubits13, motional logic gates14,15,16, motional quantum error correction17, quantum entanglement and coherent control18,19, quantum metrology with nonclassical motional states20, and communication multiplexing21, conventional echo-RIs rarely exploit the quantum interference of trapped motional states.

Recently, an RI with trapped motional states of a Bose–Einstein condensate (BEC) trapped in an anharmonic potential has been demonstrated with 92% contrast for several cycles22. This proof-of-principle experiment holds great promises for studying quantum many-body physics out of equilibrium, quantum metrology with non-classical motional states and quantum information processing with motional qubits. Recently, this new technique has been used to investigate decoherence and relaxation dynamics23, or to measure the phononic Lamb shift24.

Ultra-cold atoms trapped in an optical lattice (OL) are an ideal test platform for studying quantum many-body dynamics25, and have also been widely used as a high-precision metrology tool26. Conventionally, these atoms are prepared in the lowest band of the OL. Over last few years, there is an increasing experimental and theoretical interest to prepare atoms in higher bands27,28, opening a new way to simulate exotic orbital physics in strongly correlated matter with rich degrees of freedom, i.e., the formation of multi-flavor systems29, supersolid quantum phases in cubic lattices30, quantum stripe ordering in triangular lattices31 and Wigner crystallisation in honeycomb lattices32. A well-characterised RI with a clear understanding of the coherence mechanisms has potential applications in the study of coherence of trapped states in lattices33, nonequilibrium many body physics34, and its applications in metrology35.

In this paper, we demonstrate a RI with trapped motional quantum states (TMQS) of atoms employing the S- and D-bands in an OL. Due to the lack of selection rules for lattice band transition, a key challenge for constructing this RI is to realise π- and π/2-pulses analogous to those in conventional RIs. Using a shortcut loading method36,37, we have designed sequences of optical pulses38,39, analogous to a π- or π/2-pulse, to efficiently prepare a superposition of atoms in S- and D-band states in the OL at zero quasi-momentum with high fidelity within tens of microseconds, which is much shorter than the characteristic time scales of the decay process. Keeping the lattice on, we observe state interference and measure the decay of the coherent oscillations.

We have identified the mechanisms leading to the RI contrast reduction as following: the the homogeneity of the optical lattice depth, interaction-induced transverse expansion after loading the atoms from the harmonic trap into the optical lattice, laser intensity fluctuation and thermal fluctuations at finite temperature. We then implement a matter-wave band echo technique to significantly suppress all the contrast decay effects except for quantum and thermal fluctuations, increasing the coherence time to 14.5 ms compared to 1.3 ms without echo at condensate temperature of 50 nK and 10Er lattice depth.

Results

Experimental implementation

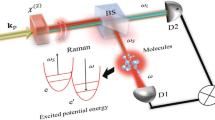

Our experiment start with a BEC of 87Rb prepared in a hybrid trap formed by a single-beam optical dipole trap with wavelength 1064 nm and a quadruple magnetic trap (Details are presented in our former works40,41). A nearly pure condensate of about 1.0 × 105 atoms at the temperature 50 nK is achieved with the harmonic trapping frequencies (ω x , ω y , ω z ) =2π × (24, 48, 58) Hz, respectively. The system’s temperature can be controlled by the evaporative cooling process (see Methods). After preparation of the condensate, a one dimensional optical lattice is formed by two counter-propagating laser beams with wavelength 852 nm resulting in a lattice constant d = 426 nm along x axis, as shown in Fig. 1(a). Using a shortcut control method38, the BEC is loaded into the lowest lattice band with the quasi-momentum q = 0 within a few microseconds with nearly 100% fidelity. The interaction energy of the condensate in the ground state of OL with a lattice depth of 10Er is 1.2 kHz (\(E_{\mathrm{r}} = \left( {\hbar k} \right)^2/2m\) is the recoil energy, k = 2π/426 nm−1 is the wave vector associated with the lattice and m is the atomic mass).

Experimental configuration for a Ramsey Interferometer in a V0 = 10Er lattice. a The BEC is divided into discrete pancakes in yz plane by an 1-dimensional optical lattice along x axis with a lattice constant d = 426 nm. b Band energies for the S-band and the D-band. c Wave-functions for the S-band and the D-band. The widths of the bands are shown by the area with0.08Er and 3.57Er, respectively. The band gap between S and D at q = 0 is 7.77Er. d Time sequences for the Ramsey interferometry. The atoms are first loaded into the S-band of OL, followed by the RI sequence: π/2 pulse, holding time t OL , and the second π/2 pulse. The dashed line indicates the time when the second π/2 pulse begins. The lattice is not shut down. Finally, band mapping is used to detect the atom number in the different bands. e The used pulse sequences designed by an optimised shortcut method

In the experiment, we construct the Ramsey interferometer with Bloch states ϕi,q with energy εi,q. We use the lowest band ϕS,0 and the second excited band ϕD,0 at quasi-momentum q = 0, denoted as |S〉, |D〉 respectively in the following, to form a superposition state ψ = a S |S〉 + a D |D〉. The two bands of S and D are considered a two-state system (spin-1/2 system), i.e., the two states can be expressed as \(\left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {a_{\rm{S}}} \\ {a_{\rm{D}}} \end{array}} \right)\). The scheme for the band energy and the superposition states are shown in Fig. 1b, c, respectively, with the lattice depth V0 = 10.0Er. During the lattice pulse sequence, an accusto-optic modulator controlled by an RF switch is used to switch on and off the lattice potential (light) quickly.

Manipulating the pseudo-spin system has its own challenges: unlike conventional RI where selection rules can be used to prepare population in two sates, the lattice band transition, similar to transition for vibration states in molecules42, has no selection rules. Thus a π/2-pulse analogous to those in conventional RIs had to be numerically designed, so that the atoms in S-band and D-band are to be transferred into the target states \(\left| {\psi _1} \right\rangle = \left( {\left| S \right\rangle + \left| D \right\rangle } \right)/\sqrt 2\) and \(\left| {\psi _2} \right\rangle = \left( { - \left| S \right\rangle + \left| D \right\rangle } \right)/\sqrt 2\), respectively. Extending our optimal control method38,39, we construct a π/2 pulse from a sequence of lattice pulses with special selected timing and duration as shown in Fig. 1(d). We achieve a fidelity of 98.5% and 98.0%, for atoms initially on the S- and D-band respectively. (see Methods).

The energy difference between S- and D-band is changing with quasi-momentum q, and the pulse sequences are desighed for q = 0. For a 10 E r lattice the applied short-cut pulses give more than 90% fidelity only in the region of q < 0.06ℏk.

The full time sequence for RI is shown in Fig. 1e. First the atoms in the harmonic trap are transferred into the S-band by a fast loading process, then the first pulse \(\hat R\left( {\pi /2}\right)\) is applied to prepare an initial superposition state \(\hat R\left( {\pi /2} \right)\left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} 1 \\ 0 \end{array}} \right) = \frac{1}{{\sqrt 2 }}\left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} 1 \\ 1 \end{array}} \right)\). The final state, after evolution in the OL for time t OL and a second π/2 pulse can be expressed as:

with \(\hat R\left( \alpha \right) = \left( {{\mathrm{cos}}\frac{\alpha }{2} - i\,{\mathrm{sin}}\frac{\alpha }{2}} \right)\hat \sigma _y\), and the evolution operator \(\hat U\left( t \right) = \left( {{\mathrm{cos}}\,\omega t + i\,{\mathrm{sin}}\,\omega t} \right)\hat \sigma _z\), here ω = (εD,0 − εS,0)/ℏ is the frequency difference between two states, and \(\hat \sigma\) the Pauli matrix, α denotes rotation angle around an axis in the Bloch sphere.

We then apply band mapping27 to read out the state of the RI. For band mapping, the lattice depth is exponentially-ramped down in the form e−t/η with a characteristic decay time η = 100 μs for a total length of 500 μs. Then absorption imaging is used to measure the population in the different bands after 31 ms time of flight (TOF) (see “Methods” section). The atoms originally occupying |S〉 state populate a narrow Gaussian distribution around 0ℏk. The atoms originally occupying the |D〉 are detected at ±2ℏk in the side zone. The total atom number we detected consists of condensed atoms and thermal atoms. From a bimodal fitting to each peak28, we can quantitatively determine the population of condensate, and we note the condensed atom number as NS (ND) for S-band (D-band) (see “Methods” section).

Ramsey Interferometer in an optical lattice

Experimental results on the time evolution of the atom population in the D-band pD(tOL) = ND/(NS + ND) with evolution time in the lattice t OL are shown in Fig. 2a for the time sequence \(\hat R\left( {\pi /2} \right) - \hat U\left( {t_{{\rm{OL}}}} \right) - \hat R\left( {\pi /2} \right)\), V0 = 10Er and T = 50 nK. Each solid point with error bar is the mean of three measurements, shown as red circles. The red solid line is a fit of an damped oscillation with a period of 41.1 ± 1.0 μs, which is consistent with the reciprocal of the band gap energy of about 40.8 μs. The details of the early RI oscillation for t OL < 100 μs is shown in Fig. 2b, displaying a nearly perfect oscillation between the S-band and the D-band with amplitude close to 1. At P1 nearly all the atoms are transmitted from the S-band to the D-band by two π/2 pulses which can be seen as a π pulse. At P2, the two π/2 pulses offset each other due to phase evolution of two states in the lattice, and the atoms are transferred to the S-band. However, when tOL gets longer, the oscillation amplitude decays, as shown in Fig. 2a. The contrast C(tOL) at t OL can be obtained by fitting the amplitude of oscillation p D (tOL) in Fig. 2a with

Signal for a Ramsey-interferometer between the S- and D-bands for V0 = 10Er. a The oscillation of the population of atoms in the D-band pD (initial temperature T = 50 nK). The dots with error-bars are the mean of three measurements, while single measurement is shown as red circle, and the red solid line is the corresponding fitting curve to the mean value. The images below show typical time of flight pictures after band mapping, the TOF images P1 is taken at 0 μs and P2 at 20 μs, the images P3 and P4 around 1.5 ms. b Detail of the oscillation for tOL < 100 μs (shown as black dots). c The decay of the interferometer contrast C(tOL) for different temperatures. The black dots, red squares and green diamonds corresponding to 50 nK, 110 nK and 180 nK, respectively, with the corresponding solid lines a guide to eye. Error-bars show the 95% confidence bounds of fitting result of the oscillation amplitude. The horizontal dashed line indicates the contrast drops to the value of 1/e that gives the coherence time τ

Figure 2c shows the measured contrast decay versus time tOL for the different initial temperatures of condensates, where each contrast value is fitted from about 20 experimental points with a time step 5 μs and each point is the mean value of three measurements. The error-bars are given by 95% confidence bounds. The horizontal dashed line in Fig. 2c indicates the contrast drops to the value of 1/e, which is used to define a coherence time τ. This time decreases from 1.3 ms to 0.8 ms when the temperature increases from 50 nK to 180 nK.

Contrast decay mechanisms

In order to improve the performance of the RI, we now investigate the mechanisms that lead to RI signal attenuation. We first study the effect of imperfect design of the π/2 pulse on the fidelity by solving Schrödinger equation with an uniform lattice potential, and the unbalanced population between the S- and D-bands (see “Methods” section). The numerical result (brown dashed line in Fig. 3a) shows that the imperfectly designing of π/2 pulses and the unbalanced population have negligible effects on the contrast decay during the evolution in lattice potential.

Contribution to contrast decay for π/2-π/2 RI. a The experimental contrast and the theoretical calculation for V0 = 10Er. The error-bars gives the 95% confidence bounds of fitting to the oscillation amplitude. In the theory, we begin with an ideal optical latice and add gradually the effect of lattice potential inhomogenity, transverse expansion of atom cloud, intensity fluctuation of laser amplitude, quantum fluctuation and the thermal fluctuation. b The coherence time versus the different depths V0. The error-bars are given by 95% confidence bounds of a quadratic fitting to experimental results at three time nearest to the coherence time

In our further theoretical analysis, we replace the ideal lattice potential by a non-uniform potential distribution to account for the Gaussian beam in the radial direction, as shown in Fig. 1a, and include the quasi-momentum distribution for the condensate distributed in the harmonic trap43. These two effects result in inhomogeneous broadening of the transition frequency ω between the S- and D-bands, and lead to to de-phasing and contrast decay. By solving the zero-temperature Gross–Pitaevskii equation(GPE) with the real inhomogeneous potential44 (see “Methods” section), we obtained the contrast as shown by the blue dotted line in Fig. 3a.

The atom-atom interaction leads to transverse expansion after the fast (non-adiabatic) loading of the atoms from the harmonic trap into the 1-d optical lattice. This expansion leads to a significant reduction on contrast (blue dashed line in Fig. 3a).

Moreover, stability of lattice depth in experiment would also influence the contrast we measured. In the GPE simulation, we investigate the influence of both the variation of intensity in a single run and the variation between different experimental runs. We find that the contrast decay shows a stronger dependence on the variation of the mean lattice depth in between different experimental runs. The variation within a single run has little influence if the mean laser power is unchanged. This is because the variation of lattice depth is small and adiabatic, and the contrast at long holding time is reduced by a variation of the mean value. Quantum fluctuations at zero temperature is further added using a truncated Wigner method (see “Methods” section) and the related results shown in green dashed line nearly overlap with the dash-dotted line. In our experiment, the atom number is high enough such that the influence by the quantum fluctuation is not significant.

Finally, we take into account the thermal fluctuations using a finite temperature truncated Wigner calculation (see “Methods” section). The result is shown in the orange solid line in Fig. 3a, agreeing well with the experimental results shown in black dots.

The relation of the coherence time to lattice depth is presented in Fig. 3b. When the lattice depth increases, the confinement in x-axis gets tighter, accordingly, the effects of the expansion in radial direction will increase due to the increased interaction energy. In addition, the non-uniformity of the lattice potential (the difference of the lattice potential from center to edge) also increases with the increasing of lattice depth. Due to these two effects, the coherence time τ decreases with increasing lattice depth. The theoretical curve in Fig. 3b, including all the decay mechanisms (orange solid line) fits well with an experimental measurement.

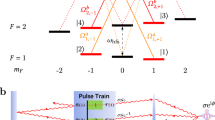

An Echo-Ramsey Interferometer with TMQS of atoms

To further improve the contrast of the RI with TMQS, we develop a matter-wave band echo technique. A π pulse is designed which swaps the atom population in S- and D-band. The pulse schema of our echo-RI scheme is shown in Fig. 4. In between the initial and final π/2 pulses we insert n identical π pulses. A single π pulse is realised with the operation \(\hat U\left( {t_{{\rm{OL}}}/2n} \right)\hat R\left( \pi \right)\hat U\left( {t_{{\rm{OL}}}/2n} \right)\). The full Echo–Ramsey pulse sequence is then: \(\hat R\left( {\pi /2} \right)\left[ {\hat U\left( {t_{{\rm{OL}}}/2n} \right)\hat R\left( \pi \right)\hat U\left( {t_{{\rm{OL}}}/2n} \right)} \right]^n\hat R\left( {\pi /2} \right)\). The contrast decay C(tOL) of a 4 × π pulse echo-RI versus the holding time at various temperatures between 50 nK and 180 nK is shown in Fig. 5a. The solid lines are fits with an exponential function, which allow to extract the coherence time τ.

Echo-Ramsey Interferometer. a Contrast C vs holding time t OL in the OL after using four π pulses. Solid curves are a fit with an exponential function to extract the coherence time τ. b Coherence time τ vs the number of applied π pulse n. The circle and cross are theoretical results at zero temperature with or without intensity fluctuations respectively. Experimental results and fitting curves with parameter β for the different temperatures are also shown. The error-bars are given by 95% confidence bounds of a quadratic fitting to experimental results at three time nearest to the coherence time. c Experimental (red dots) decay rate β induced by thermal fluctuations vs. temperature. The error-bars give a 95% confidence interval. The dashed line illustrates that the decay rate β is proportion to the temperature

The relationship between the coherence time τ and the number of π pulses n is shown in Fig. 5b for three different temperatures (T = 50, 110 and 180 nK). The zero-temperature theoretical results of the coherence time can again be obtained by solving the GPE including the non-uniform lattice potential and the radial expansion, as shown by the circles in Fig. 5b. When further taking into account of the laser intensity fluctuation, the calculated coherence time is shown with the cross points. After implementing one π pulse, the two theoretical points merger together, which shows that the intensity fluctuation can be well suppressed with one π pulse; however, in order to eliminate the effects of non-uniform lattice potential and transverse expansion, more echo pulses are needed; after applying n = 6 echo pulses, the theoretical curves get nearly flat, showing that the two effects are well suppressed. There remains a significant discrepancy between the experimental and the zero temperature theoretical calculations, which we attribute to thermal fluctuations. Lowering the condensate temperature, the thermal fluctuations get weaker, and the coherence time can be greatly increased with multiple echo-pulses. The measured coherence time τ for the RI at T = 50 nK is 14.5 ms, which is one order of magnitude longer than the case without echo-pulses.

We will now look at the remaining fluctuations that cannot be suppressed by the echo technique: We fit the experimental contrast with C0(tOL)exp[−βtOL], where C0 is the calculated contrast for zero temperature and the decay rate β characterises the additional decay. For different temperatures, the fitted values of β are shown in Fig. 5c with red dots, showing a linear dependence on the temperature. This is a strong indication that the remaining decay of the interference contrast of the echo–Ramsey interferometer is caused by thermal fluctuations. To confirm this, we conducted finite temperature truncated Winger calculations45,46 (see “Methods” section)

Finally, we look at the performance of the echo-RI for different lattice depth. As shown in Fig. 6a, the contrast decay rate strongly depends on the lattice depth for a condensate at 50 nK and using a sequence with six π pulses. The decay rate is small at medium optical lattice depth, and it becomes bigger for the shallow (<5Er) and deep lattices (<10Er). For the case of V0 = 4Er, the separation between D- and P-bands is small and it is hard to form a closed cycle between S- and D-band without any transition to P-band in practice. We should note that for the two pulse RI, transition to other bands is not so evident due to the short lattice time. When the echo technique is applied, the coherence time is much increased, and transition to other bands induced by atom-atom interaction become important. This can be seen in Fig. 6b, where the momentum distribution for 4Er has components (marked with a red square) different from ±2ℏk.

Contrast decay at different lattice depth. a The contrast decay rate from thermal effect β versus the different lattice depth V0 with six π pulses and T = 50 nK with the fitting results (solid points) and theoretical calculation at 50 nK (square points). Error-bars show a confidence interval of 95%. The error in theory reflect the variation in parameters like atom number, temperature and the different stochastic initial states (see Methods). Testing the significance of the model, we find the theory curve gives a χ2 that is more than 3 times smaller than a model, where β is independent of the lattice depth (red dashed line). This indicates a statistical significant better agreement between theory and experiment then just an potential depth independent decay rate β. b Typical TOF images for different lattice depths and the red square shows atom on other momentum, which causes an increasing of decay rate in experiment

When the lattice potential gets deeper, the band separation increases, and the coherence time increases accordingly. However, when the lattice depth is more than 10Er, the coherence time decreases quickly. In fact the probability for atoms to be excited to higher momentum states by the pulse is proportional to the lattice depth. For a very deep lattice the atoms can easily obtain higher momenta47. In Fig. 6b, the momentum distributions clearly show the components at 4ℏk for 20 Er. Since the Rabi transition is designed for the transition between the S- and D-band at zero quasi-momentum, the higher states will lead to a reduced pulse fidelity and a faster decay of the contrast.

Discussion

In summary, we have demonstrated a Ramsey interferometer for atoms within an OL. We further employ a matter wave band echo technique to significantly enhance the coherence time by one order of magnitude. We have identified the mechanisms leading to the contrast decay for the RI signal. The contrast decay is closely related to the homogeneity of the optical lattice, laser intensity fluctuation and interaction-induced transverse expansion, and finite temperature dynamics of a BEC. All except for the effects of finite temperature can be suppressed by a matter-wave band echo sequence. Thus, the damping from thermal fluctuations is well uncovered in this way.

So far, the π pulses and π/2 pulses for echo-RI using TMQS are designed based on zero temperature single atom dynamics. In future developments, it would be interesting to unveil quantum many body dynamics in OL, like loop structures and swallowtails48,49,50. These deliberate quantum control technologies could be applied in quantum information and precise measurements based on TMQS of atoms.

Methods

Design of Pi/2- and Pi-pulses

In a 1D optical lattice along x-direction, the eigen-states of the atom, i.e. the Bloch states, can be expressed as the superposition of momentum states \(\left| {i,q} \right\rangle = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{l = - \infty }^{ + \infty } c_{i,l}\left( q \right)\left| {2l\hbar k + q} \right\rangle ,\) where |2lℏk + q〉 is the basis in momentum space, i is the band index and q is the quasi-momentum, ci,l(q) is the superposition coefficient with l = 0, ±1, ±2,.... While the target state is considered to be the superposition of Bloch states, \(\psi = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_i A_i\left| {i,q} \right\rangle = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_i A_i\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_l c_{i,l}\left( q \right)\left| {2l\hbar k + q} \right\rangle\) with A i is the superposition coefficient.

Varying the pulse parameters, we numerically find a time sequence {t1 = 0, t2, t3,...} of optical lattice pulses

that creates a \(\frac{\pi }{2}\) pulse in the Ramsey interferometer, i.e., after this operation, the atoms on S-band and D-band are transferred into target states \(\left( {\left| S \right\rangle + \left| D \right\rangle } \right)/\sqrt 2\) and \(\left( { - \left| S \right\rangle + \left| D \right\rangle } \right)/\sqrt 2\), respectively. In our designed pulse sequences, both the laser intensity and the duration can be changed. From the numerical simulation, we find that with a fixed laser intensity our designed pulse sequence can still reach high fidelity and is easier to realize in the real experiment. So we keep the lattice depth constant and only change the time sequence in the design for experimental simplicity without losing of fidelity.

The evolution operator for t2i−1 < t < t2i is

and

for the free evolution operator at t2i < t < t2i+1, where p and m are,, respectively, the momentum and mass of a single atom. After applying the pulse sequence, the final states \(\left| {\psi _{f_1}} \right\rangle\) and \(\left| {\psi _{f_2}} \right\rangle\) can be written as

By changing the parameters of the pulse sequence, one can maximise the two fidelities F1 = \(F_1 = \left| {\left\langle {\psi _{A_1}|\psi _{f_1}} \right\rangle } \right|^2\) and \(F_2 = \left| {\left\langle {\psi _{A_2}|\psi _{f_2}} \right\rangle } \right|^2\). For V0 = 10Er, the time sequence for π/2 pulse as {0, 56.2, 84.2, 106.8, 129.9}(μs) with F1 = 96.9%,F2 = 97.9%.

The method for designing π pulse is similar to the case of π/2 pulse, but with other target states. After the sequence of optical lattice pules, the atoms should be transferred from |S〉 or |D〉 into the target states |D〉 or −|S〉, respectively. For V0 = 10Er, the time sequence for π pulse as {0, 49.2, 101.7, 123.8, 150.2}(μs), and the transfer of |S〉 and |D〉 to the target states are with the fidelity 98.5% and 98.0%, respectively.

During design of the pulse sequences, we have neglected atom-atom interaction because the duration of pulses is short enough and atom-atom interaction strength in our system is weak38. Numerical results of the GPE with atom-atom interaction show that the interaction leads to a change of fidelity <1% compared with our designed time sequence.

Data analysis

After the band mapping, we release the condensate from the trap and let it expand freely for 31 ms to perform time of flight (TOF) imaging. The TOF image shows the atoms from the S-band distributed in the center 0ℏk, while atoms from the D-band are distributed on the side zone ±2ℏk. We apply an algorithm to remove the background fringes51, and integrate the atom distribution in y-direction of the TOF image. Then the atomic distribution is fitted with a bimodal function

with a Gaussian thermal distribution F th and a Thomas Fermi like the condensate. i = 1,2,3 corresponds to the three atom clouds for −2ℏk, 0ℏk, and 2ℏk, respectively. We also add a restriction to all six amplitude terms H i and G i as H1/G1 = H3/G3. From the amplitude of each component H i and the width of condensate part χ i ,, we can determine the population of condensate in the S-band N S and in the D-band N D , and further calculate the population of the D-band as pD(tOL) = ND / (NS + ND). The experimental contrast at a certain time is given by fitting the measured amplitude of oscillation pD for 100 μs (about 2.5 periods) with a time step 5 μs using a cosine function, where the errorbar is given by the fitting error with 95% confidence bounds.

Contrast decay induced by atom-atom interaction

When atoms collide in the excite band they can decay to a lower band52,53. We calculate the collision decay of atom population in different bands using a simple rate equation model39,

where the factor KS(D) is given by summation of cross-section of the two-atom inelastic collision from different channels. Solving Eq.(10), the population from the D-band ND(t) decays as 1/(1 + t/τD), with the time constant of atom decay from the D-band given by 1/τD = KDND. NS(t) can similarly be given from the collision rate of atoms between the S- and the D-bands.

We measure the collisional decay rate of atoms in different bands by band mapping without the final π/2 pulse and get τD = 1.9 ± 0.3 ms, τS = 5.1 ± 0.8 ms.

During the collision decay, the potential energy of the D-band is transferred to kinetic energy in radial direction. This energy is large enough so that the majority of the decayed atoms will not be counted in for the condensed peaks. After the population decay atom number N S (t) and ND(t) is unbalanced, which leads to a reduction of the contrast by a factor \(\frac{{2\sqrt {N_SN_D} }}{{N_S + N_D}}\). From the measured NS and ND, we find that the influence of this population unbalance to the calculated contrast C0(t OL ) is less than 1% for an experiment with t OL < 2 ms as shown as the brown dashed line in Fig. 3a.

Applying the repeated π-pulses, the coherence time is much longer than this decay time: (i) The π-pulses reverse the population in the S- and D-bands, and therefore prevent a strong imbalance. (ii) In the data analysis, extract the remaining condensed part by bimodal fitting. Both together dramatically reduce the effect of collisional decal on the contrast of the observed interference between the remaining coherent parts, and the collisional decay time does not limit the coherence time of our interferometer signal, as long as the remained population in condensed part is large enough for detection.

The contrast decay induced by the quasi-momentum distribution and the nonuniform of optical lattice potential in radial direction

For these, we have to turn to numerical calculations taking the real potentials and their variation into account. Considering that the trapping frequencies in y,z-directions are very similar in our system, we can use use a mean field model (GPE) in cylindrical coordinates to describe the system at zero temperature. The evolution of the wave function Φ(r, t) is governed by

where r = (x, r, θ), Vext is the external potential, and \(U_0 = \frac{{4\pi \hbar ^2a_s}}{m}\) is the interaction term with a s the scattering length.

In our case, the radial part of wavefunction is in the ground state and uniform in θ coordinate. The lattice potential itself depends on the radial position r. We first neglect the kinetic term in radial direction and separate the wavefunction into radial part and axial part as \({\mathrm{\Phi }}\left( {r,t} \right) = \frac{1}{{\sqrt {2\pi } }}\psi \left( {x,t} \right)\phi \left( r \right)\), then Eq. (11) can be simplified to the following 1d GPE at a certain value r = r i as

\(V_{{\mathrm{ext,r}}_{\mathrm{i}}}\) is the combination of both harmonic potential \(V_{{\mathrm{trap}}} = \frac{m}{2}\omega _x^2x^2\) and lattice potential \(V_{{\mathrm{latt}},r_i} = V_0Q\left( t \right)e^{ - 2r_i^2/w_{{\mathrm{latt}}}^2}{\rm{cos}}^2\left( {kx} \right),\) where Q(t) takes value 0 or 1 depending on the time sequence, and wlatt is the waist of lattice laser. \(\rho _{r_i} = \frac{{{\mathrm{exp}}\left[ { - m\omega _rr_i^2/\hbar } \right]}}{{\sqrt {\pi \hbar /m\omega _r} }}N\) is the linear density. We solve Eq. (12) to get the ψ(x, t) and the population in the D-band \(p_{D_i}\) for position r i . We then calculate 30 different radial positions and take their weighted average according to the atom number distribution \(\mathop {\sum}\limits_i {\left( {2\pi r_i\rho _{r_i} \cdot p_{D_i}} \right)} /\mathop {\sum}\limits_i {\left( {2\pi r_i\rho _{r_i}} \right)}\). Finally, the oscillation amplitude of the average p D is fitted to get a contrast as shown in dotted line in Fig. 3a.

In this simulation, we consider the wave-function’s distribution instead of using a single atom model, thus the influence of quasi-momentum distribution is also included automatically.

Contrast decay induced by radial motion of the condensate

In the above calculation, we consider the distribution of lattice potential in radial direction, however, the radial size of he wave function also changes with time. To consider this effect, we need to estimate the expansion speed of the atom cloud in this direction.

We can take each site of the lattice as a small independent BEC with about 1.5 × 103 atoms (about 65 lattice sites), and calculate how it spreads after the trapping potential changed during switch on and loading into the lattice. When the lattice is turned on, the trapping frequency in x-direction increases to 20 kHz for 10Er, which is much larger than the harmonic trap of 2π × 24 Hz, this sudden increase of trap frequency induces the spread in the radial direction, which can be calculated as54,

where \(\omega _x,\omega _r = \sqrt {\omega _y\omega _z}\) are the frequency of the effective trapping potential in x and r-directions for the small BECs in each lattice site, respectively, and λ r = r i (t)/r i (0) is the expansion with r i (0) the initially radial position. Using this time-dependent radial expansion, we then follow a procedure like above to calculate the average p D and contrast as shown in dashed line in Fig. 3a of the main text.

Contrast decay induced by laser intensity fluctuations and thermal fluctuations

The laser intensity in our experiment fluctuates by about 0.1% during the holding time. The laser intensity changes are slow and do not cause excitation between the different bands. Simulations like above are then repeated with different laser intensities sampled from the measured fluctuations. The averaged result is shown in Fig. 3 of the main text with the purple dash-dotted line.

To calculate that contrast decay induced by thermal fluctuations we apply the finite-temperature truncated Wigner method45. We solve the 1d GPE with a stochastic initial wave function \(\psi \prime \left( x \right) = \psi + \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_j {\psi _j}\), where ψ is the zero-temperature condensate wave-function within the one-dimensional optical lattice, ψ j corresponding to the thermal fluctuations that is given by \(\psi _j = A\left( {r_0,\theta _0} \right)\left[ {u_j\left( x \right)\beta _j - v_j^ \ast \left( x \right)\beta _j^ \ast } \right]\), where \(A\left( {r_0,\theta _0} \right) = \sqrt {n_0\left( {0,r,\theta } \right)/{\int\!\!\!\int} n_0\left( {0,r,\theta } \right)r{\mathrm{d}}r{\mathrm{d}}\theta }\), with the condensation density n0(x, r, θ). For simplicity and without loss of generality, we choose r0 = 0,θ0 = 0. Here β j is a complex number with random phase which satisfies \(\beta _j^ \ast \beta _j = \bar N_j + 1/2\), where the quantum fluctuations are included by the 1/2 term. in which \(\bar N_j = \mathop {\sum}\limits_i {1/\left( {e^{E_{ji}/k_BT} - 1} \right)}\) and E ji = E j + Λ i is the summation of the energy of the jth Bogoliubov mode E j plus the ith eigen-energy Λ i of the radial harmonic potential. u j and v j are the jth Bogoliubov modes solved from the one-dimensional Bogoliubov de Gennes equation as45,

with

In the calculation, we use 300 excitation modes and repeat our simulation 15 times with different stochastic initial states. From the wave functions and the population distributions, we then obtain the contrast C(tOL), calculated at the different holding times tOL, which can then be compared to the experiment. In a separated calculation, we also calculate for the quantum fluctuations by taking \(\bar N_j = 0\), the result is shown in Fig. 3a of the main text with green dashed line, which is close to the result without quantum fluctuations, where the coherent time is only reduced by 0.2%.

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. Extra data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ramsey, N. F. A new molecular beam resonance method. Phys. Rev. 76, 996 (1949).

Ramsey, N. F. Molecular Beams (Oxford University Press, 1985).

Chebotayev, V. P., Dubetsky, B., Ya., Kasantsev, A. P. & Yakovlev, V. P. Interference of atoms in separated optical fields. JOSA B 2, 1791–1798 (1985).

Bordé, Ch. J. Atomic interferometry with internal state labelling. Phys. Lett. A 140, 10–12 (1989).

Riehle, F., Kisters, Th, Witte, A., Helmcke, J. & Bordé, Ch. J. Optical ramsey spectroscopy in a rotating frame: Sagnac effect in a matter-wave interferometer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 177–180 (1991).

Staudacher, T. et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy on a (5-Nanometer)3 sample volume. Science 339, 561–563 (2013).

Santarelli, G. et al. Quantumprojection noise in an atomic fountain: a high stability cesium frequencystandard. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 4619–4622 (1999).

Maître, X. et al. Quantum memory with a single photon in a cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 769–772 (1997).

Cetina, M. et al. Ultrafast many-body interferometry of impurities coupled to a Fermi sea. Science 354, 96–99 (2016).

Cronin, A. D., Schmiedmayer, J. & Pritchard, D. E. Optics and interferometry with atoms and molecules. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 1051–1129 (2009).

Zhang, S. M., Meier, B. H. & Ernst, R. R. Polarization echoes in NMR. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 2149 (1992).

Yan, B. et al. Observation of dipolarspin-exchange interactions with lattice-confined polar molecules. Nature 501, 521–525 (2013).

Negretti, A., Treutlein, P. & Calarco, T. Quantum computing implementations with neutralparticles. Quant. Inf. Proc. 10, 721 (2011).

Lee, P. J. et al. Phase control of trapped ion quantum gates. J. Opt. B: Quant. Semiclass. Opt. 7, S371 (2005).

Wineland, D. J. et al. Experimental issues in coherent quantum-statemanipulation of trapped atomic ions. J. Res. Nat. Inst. Stand. Technol. 103, 259–328 (1998).

Briegel, H. J., Calarco, T., Jaksch, D., Cirac, J. I. & Zoller, P. Quantum computing with neutral atoms. J. Mod. Opt. 47, 415–451 (2000).

Steinbach, J. & Twamley, J. Motional quantum error correction. J. Mod. Opt. 47, 453–485 (2000).

Sangouard, N., Simon, C., Riedmatten, H. & Gisin, N. Quantum repeaters based on atomic ensembles and linear optics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 33–80 (2011).

Zhuang, C. et al. Coherent control of population transfer between vibrational states in an optical lattice via two-path quantum interference. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 233002 (2013).

Dalvit, D., Filho, R. & Toscano, F. Quantum metrology at the Heisenberg limitwith ion trap motional compass states. New J. Phys. 8, 276 (2006).

Garaot, S. M. et al. Vibrational mode multiplexing of ultracold atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 213001 (2013).

van Frank, S. et al. Interferometry with non-classical motional states of a Bose-Einstein condensate. Nat. Comm. 5, 4009 (2014).

Scelle, R., Rentrop, T., Trautmann, A., Schuster, T. & Oberthaler, M. K. Motional Coherenceof Fermions Immersed in a Bose Gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 070401 (2013).

Rentrop, T. et al. Observation of the Phononic Lamb Shift with a Synthetic Vacuum. Phys. Rev. X. 6, 041041 (2016).

Bloch, I., Dalibard, J. & Zwerger, W. Many-body physics with ultracold gases. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 885–964 (2008).

Derevianko, A. & Katori, H. Colloquium: Physics of optical lattice clocks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 331–347 (2011).

Müller, T., Fölling, S., Widera, A. & Bloch, I. State preparation and dynamics ofultracold atoms in higher lattice orbitals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 200405 (2007).

Schori, C., Stöferle, T., Moritz, H., Köhl, M. & Esslinger, T. Excitations of asuperfluid in a three-dimensional optical lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 240402 (2004).

Krauser, J. S. et al. Coherent multi-flavour spin dynamics in a fermionic quantum gas. Nat. Phys. 8, 813–818 (2012).

Pinheiro, F., Bruun, G. M., Martikainen, J. P. & Larson, J. XYZ quantum Heisenberg models with p-orbitalbosons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 205302 (2013).

Wu, C., Liu, W. V., Moore, J. & Sarma, S. D. Quantum stripe ordering in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 190406 (2006).

Wu, C., Bergman, D., Balents, L. & Sarma, S. D. Flat bands and Wigner crystallization in the honeycomb opticallattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 070401 (2007).

Morsch, O. & Oberthaler, M. Dynamics of Bose-Einstein condensates in optical lattices. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 179–215 (2006).

Langen, T., Geiger, R. & Schmiedmayer, J. Ultracold Atoms Out of Equilibrium. Ann. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 6, 201–217 (2015).

Rentrop, T. et al. Observation of the Phononic Lamb Shift with a Synthetic Vacuum. Phys. Rev. X. 6, 041041 (2016).

Masuda, S., Nakamura, K. & Campo, A. D. High-fidelityrapid ground-state loading of an ultracold gas into an optical lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 063003 (2014).

Chen, X. et al. Fast optimal frictionless atom cooling inharmonic traps: Shortcut to adiabaticity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 063002 (2010).

Liu, X. X., Zhou, X. J., Xiong, W., Vogt, T. & Chen, X. Z. Rapid nonadiabatic loading in an optical lattice. Phys. Rev. A 83, 063402 (2011).

Zhai, Y. Y. et al. Effective preparation and collisional decay of atomiccondensates in excited bands of an optical lattice. Phys. Rev. A 87, 063638 (2013).

Wang, Z. K. et al. Observation of quantum dynamicaloscillations of ultracold atoms in the F and D bands of an opticallattice. Phys. Rev. A 94, 033624 (2016).

Hu, D. et al. Long-time nonlinear dynamical evolutionfor P-band ultracold atoms in an optical lattice. Phys. Rev. A 92, 043614 (2015).

Kneipp, K. et al. Population pumping of excited vibrational states by spontaneous surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 2444–2447 (1996).

Horikoshi, M. & Nakagawa, K. Suppression of dephasing due to a trapping potential and atom-atom interactions in atrapped-condensate interferometer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 180401 (2007).

Dalfovo, F., Giorgini, S., Pitaevskii, Lev, P. & Stringari, S. Theory of Bose-Einstein condensation in trapped gases. Rev. Mod. Phys. 71, 463–512 (1999).

Scott, R. G., Hutchinson, D. A. W., Judd, T. E. & Fromhold, T. M. Quantifying finite-temperature effects in atom-chip interferometry of Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 79, 063624 (2009).

Isella, L. & Ruostekoski, J. Nonadiabatic dynamics of a Bose-Einstein condensate in an optical lattice. Phys. Rev. A 72, 011601(R) (2005).

Zhai, Y., Zhang, P., Chen, X., Dong, G. & Zhou, X. Bragg diffraction of a matter wave driven by a pulsed nonuniform magnetic field. Phys. Rev. A 88, 053629 (2013).

Yoon, S., Dalfovo, F. & Watanabe, G. Swallowtail band structure of the superfluid Fermi gas in an optical lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 270404 (2011).

Seaman, B. T., Carr, L. D. & Holland, M. J. Period doubling, two-color lattices, and the growth of swallowtails in Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 72, 033602 (2005).

Koller, S. B. et al. Nonlinear looped band structure of Bose-Einstein condensates in an optical lattice. Phys. Rev. A 94, 063634 (2016).

Ockeloen, C. F., Tauschinsky, A. F., Spreeuw, R. J. C. & Whitlock, S. Detection of small atom numbers through image processing. Phys. Rev. A 82, 061606(R) (2010).

Spielman, I. B. et al. Collisional de-excitation in a quasi-two-dimensional degenerate bosonic gas. Phys. Rev. A 73, 020702(R) (2006).

Bücker, R. et al. Twin Atom Beams. Nat. Phys. 7, 608–611 (2011).

Castin, Y. & Dum, R. Bose-Einstein Condensates in time dependent traps. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 5315–5319 (1996).

Acknowledgements

We thank Z. K. Chen for the calculation of pulse time sequences and discussion. Thank P. Zhang, Q. Zhou, and B. Wu for helpful discussion. This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2016YFA0301501), and the NSFC (Grant Nos. 11334001, 61727819, 61475007, 91736208). G. J. Dong acknowledges the support by the National Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 11574085 and No. 91536218), and 111 Project (B12024), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2017YFA0304200). JS acknowledges support by the European Research Council, ERC-AdG QuantumRelax.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Z. designed the experiment, D.H., S.J. and L.N. performed the measurement, L.N. and D.H. analysed the data supervised by X.Z. and J.S., S.J. and L.N. did the theoritical calculations and modelling supervised by X.Z., J.S., G.D. and X.C.. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the result and writing of the manuscript. D.H. and L.N. contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, D., Niu, L., Jin, S. et al. Ramsey interferometry with trapped motional quantum states. Commun Phys 1, 29 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-018-0030-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-018-0030-7

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.