Abstract

Artificial photosynthesis is a desirable critical technology for the conversion of CO2 and H2O, which are abundant raw materials, into fuels and chemical feedstocks. Similar to plant photosynthesis, artificial photosynthesis can produce CO, CH3OH, CH4, and preferably higher hydrocarbons from CO2 using H2O as an electron donor and solar light. At present, only insufficient amounts of CO2-reduction products such as CO, CH3OH, and CH4 have been obtained using such a photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical conversion process. Here, we demonstrate that photocatalytic CO2 conversion with a Ag@Cr-decorated mixture of CaGa4O7-loaded Ga2O3 and the CaO photocatalyst leads to a satisfactory CO formation rate (>835 µmol h−1) and excellent selectivity toward CO evolution (95%), with O2 as the stoichiometric oxidation product of H2O. Our photocatalytic system can convert CO2 gas into CO at >1% CO2 conversion (>11531 ppm CO) at ambient temperatures and pressures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations in the atmosphere have increased drastically over the past few centuries owing to the combustion of carbon-rich fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas. As a major anthropogenic greenhouse gas, these ever-increasing CO2 emissions are detrimental to the environment and will affect both ecosystems and the global climate1. Therefore, there is a critical requirement of mitigating CO2 emissions to achieve sustainable development. Since the pioneering work on the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 into formic acid (HCOOH) and methyl alcohol (CH3OH) over semiconductors reported by Halmann and Inoue et al.2,3, the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 into other valuable feedstocks at ambient temperatures and pressures has attracted considerable attention from the scientific community as a feasible strategy for CO2 storage and conversion4,5,6,7,8.

In general, the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 over an excited semiconductor-based catalyst involves three main steps. First, CO2 molecules are adsorbed on the photocatalyst surface9,10,11. Second, the photogenerated electrons react with the adsorbed CO2 species and protons (H+) to yield products such as carbon monoxide (CO), methane (CH4), CH3OH, and HCOOH. Among these possible reduction products, CO is one of the most useful because it is widely combined with H2 to provide synthetic gas for use in many chemical processes, such as methanol synthesis12,13 and the industrial Fischer–Tropsch process that produce various chemicals and synthetic fuels14,15. Third, the products are desorbed from the photocatalyst surface. However, as the H/H2 redox potential (−0.41 V vs. NHE at pH 7) is more positive than that for CO2/CO (−0.52 V vs. NHE at pH 7), the generation of H2 from H+ is preferable for the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 into CO, where H2O acts as the electron donor16,17,18. Moreover, because of the high thermodynamic stability of the linear CO2 molecule, the fixation and activation of CO2 are also immense challenges in the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 by H2O4,19. Thus, although various heterogeneous photocatalysts have been reported for the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 into CO with H2O as the electron donor20,21,22,23,24, the photocatalytic activity for CO evolution remains limited to a few micromoles, while the photocatalytic conversion rate of CO2 into CO is <0.15%.

Based on the processes involved in the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 described previously, we deduce that the photocatalytic activity of the photocatalyst for CO2 conversion can be improved by increasing CO2 adsorption, charge separation, and product desorption. Due to the fact that CO2 acts as a Lewis acid that bonds easily with Lewis bases25, many studies have focused on improving CO2 adsorption by modifying the photocatalyst surface with a CO2 adsorbent, such as NaOH26, amino groups27, and rare earth species28, to increase the photocatalytic activity and selectivity for CO2 conversion by H2O. Our group reported that modifying the photocatalyst surface with alkaline earth metals (e.g., Ca, Sr, and Ba) enhanced the conversion of CO2 and the selectivity toward CO evolution29. Moreover, we found that a Ag@Cr core/shell cocatalyst suppresses the backward reaction from CO and O2 to CO2, and enhances the adsorption of CO2, resulting in a highly selective photocatalytic CO2 conversion30,31.

In this study, we exploited the above techniques and successfully fabricated a Ag@Cr-decorated mixture of CaGa4O7-loaded Ga2O3 and CaO photocatalyst, which exhibits a high CO formation rate (>835 µmol h−1) per 0.5 g of catalyst, in addition to high selectivity toward CO evolution (>95%) with the stoichiometric production of O2 as the oxidation product of H2O during the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 by H2O. Approximately 1.2% of the CO2 in the gas phase was transformed into CO (11531 ppm) as a product. The results reported in this study represent almost an order of magnitude higher than most previously published results, as summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Results and discussion

Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 by H2O

Table 1 shows the formation rates of CO, H2, and O2, selectivity toward CO evolution, and the balance between consumed electrons and holes over the bare Ga2O3, Ag-modified Ga2O3 (Ag/Ga2O3), Ag@Cr-modified Ga2O3 (Ag@Cr/Ga2O3), and Ag@Cr-modified Ca-loaded Ga2O3 (Ag@Cr/Ga2O3_Ca) photocatalysts during the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 by H2O. No liquid products were detected in the reaction solutions in these photocatalytic systems, and H2, O2, and CO were detected as gaseous products. As no reduction products other than H2 and CO were generated, the selectivity toward CO evolution and the balance between the consumed electrons and holes were calculated as follows:

where RCO and RH2 represent the formation rates of CO and H2, respectively. If H2O acts as an electron donor, the value of e−/h+ should be equal to 1.

We obtained stoichiometric amounts of H2 and CO as reduction products in addition to O2 as the oxidation product, indicating that H2O serves as the electron donor. Bare Ga2O3 exhibited a particularly low selectivity toward CO evolution (4%) as the electrons generated by charge transfer were not consumed in the reduction of CO2, but rather in the production of H2 from H+. Modifying Ga2O3 with a Ag cocatalyst enhanced the selectivity toward CO evolution (29%); however, this was not sufficient to obtain a selectivity >50%. In contrast, we succeeded in the selective photocatalytic conversion of CO2 by H2O over Ag@Cr/Ga2O3. A relatively high CO formation rate (499.6 µmol h−1) was achieved with 77% selectivity toward CO evolution. The photocatalytic reaction for the conversion of CO2 by H2O over Ag@Cr/Ga2O3 and Ag@Cr/Ga2O3_Ca was carried out for at least four times, and errors in the product formation rates (H2, O2, and CO) were smaller than 5%. Controlling both, the bulk and surface of the photocatalysts, is highly important for achieving a considerably high CO formation rate and selectivity toward CO evolution. We found that the amount of Ca species significantly affected the H2 and CO formation rates (for the product formation rates and selectivity over various Ag@Cr/Ga2O3_Ca photocatalysts see Supplementary Fig. 1). The formation rate of CO increased first and then decreased as the Ca content increased (Supplementary Fig. 1a–g). In contrast, the formation rate of H2 over the Ag–Cr/Ga2O3_Ca_x samples increased monotonically with increasing amount of Ca species. The Ag–Cr/CaGa4O7 photocatalyst was only active for H2 evolution derived from water splitting (Supplementary Fig. 1h). The Ag@Cr/Ga2O3_Ca photocatalyst exhibited the highest CO formation rate (794.2 µmol h−1), and the selectivity toward CO evolution was approximately 82%. Additionally, CO production from the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 after photoirradiation for 15 h over Ag@Cr/Ga2O3_Ca was more stable than that over Ag@Cr/Ga2O3 (for the product formation rates for 15 h see Supplementary Fig. 2), which indicates that the presence of Ca species is not only beneficial for improving the photocatalytic activity and selectivity, but also for improving stability during the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 to CO.

Various control experiments were carried out to confirm the source of CO during the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 by H2O, the results of which are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. We did not detect any appreciable amounts of products under dark conditions or in the absence of a photocatalyst. In addition, H2 was the main product formed when Ar gas was used instead of CO2 or in the absence of NaHCO3. The control experiments confirmed that the evolved CO originated from the CO2 gas introduced into the samples and not from carbon contaminants.

Photocatalyst characterization

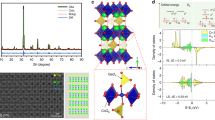

The actual amounts of the Ca species loaded into Ga2O3 at different CaCl2 concentrations were measured using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) (Supplementary Table 2). We found that almost all the Ca species were loaded into the Ga2O3 photocatalyst when the CaCl2 concentration was <0.001 mol L−1. However, not all the Ca species could be loaded into Ga2O3 at higher CaCl2 concentrations. Note that even when no CaCl2 was added during the preparation of Ga2O3, trace amounts of Ca were detected in Ga2O3, which is likely due to Ca impurities present in the experimental vessels or precursor reagents. Hereinafter, we refer to the Ca-loaded Ga2O3 photocatalysts as Ga2O3_Ca_x (x = 0.32, 0.62, 1.1, 1.6, 2.1, 3.3 mol%) based on the Ca/Ga molar ratio determined by ICP-OES. Figure 1a shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the bare Ga2O3, Ga2O3_Ca_x, and CaGa4O7 photocatalysts. As indicated, gradual changes in the diffraction peaks assigned to the (020), (311), (400), (002), and (330) facets of CaGa4O7 (JSPDS 01-071-1613) were observed as the amount of Ca species was increased. In general, a high Ca loading is favorable for the formation of CaGa4O7. We observed no distinct shifts in the diffraction peaks for the Ga2O3_Ca_x samples compared with those of bare Ga2O3. As the ionic radius of Ca2+ (0.099 nm)32 is larger than that of Ga3+ (0.062 nm)33, the unshifted XRD peaks imply that Ca2+ does not act as a dopant in the bulk Ga2O3 lattice. However, there was a clear increase in the peak intensity at 2θ = 30.1° and an apparent decrease in that at 2θ = 30.5° with increasing amount of Ca species (Fig. 1b), which are possibly ascribed to the formation of CaGa4O7 species on Ga2O3. The increased intensity of the Ca 2p X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) peak (Fig. 1c) also indicates that the amount of Ca species on the Ga2O3 surface increased with increasing Ca levels. In addition, the XPS peak locations in the Ca 2p spectra of the Ga2O3_Ca_x photocatalysts are similar to those of CaGa4O7, but different from those of CaO. The Ca 2p XPS profiles suggest that a thin CaGa4O7 layer forms on the Ga2O3 surface and that the amount of CaGa4O7 increases as the amount of Ca is increased. We further confirmed the morphological changes in the Ga2O3_Ca sample by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM), as shown in Fig. 1d. Both ends of the Ga2O3 nanoparticles gradually sharpened and their surfaces became smoother as the amount of Ca species increased, especially when the Ca amount was higher than 1.1 mol%. This smoothing of the Ga2O3 surfaces with increasing Ca/Ga molar ratio resulted in a decrease in the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) specific surface area of Ga2O3_Ca_x (Supplementary Fig. 4), which is attributable to the modification of CaGa4O7, as we confirmed from the XRD patterns and the XPS results that a CaGa4O7 layer was formed on the Ga2O3 surface.

a X-ray diffractograms; b enlarged X-ray diffractograms at 2θ = 29–31°; c Ca 2p X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy profiles; and d field-emission scanning electron microscopy images of A bare Ga2O3; Ga2O3_Ca_x with a Ca/Ga molar ratio x of B 0.32 mol%, C 0.62 mol%, D 1.1 mol%, E 2.1 mol%, and F 3.3 mol%; G CaGa4O7 (in a, b), and H CaO (in c).

The close linkage between CaGa4O7 and Ga2O3 on the Ga2O3 surface was confirmed by field-emission transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) (Fig. 2). The marked lattice spacings (0.296 and 0.255 nm) in Fig. 2b correspond to the (130) and (111) planes of CaGa4O7 and Ga2O3, respectively. The core–shell-structured Ag@Cr cocatalyst was successfully loaded onto the Ga2O3_Ca surface using the photodeposition method (Fig. 2c, d), as reported previously by us31.

Role of the Ca species

Figure 3 shows the Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of the CO2-adsorbed samples after introducing CO2 at ~0.2 Torr. When CO2 was introduced into the Ga2O3 sample, three absorbance peaks were observed at 1634, 1432, and 1225 cm–1, which can be ascribed to asymmetric CO3 stretching vibrations [νas(CO3)], symmetric CO3 stretching vibrations [νs(CO3)] of monodentate bicarbonate species (m-HCO3-Ga), and OH deformation vibrations [δ(OH)], respectively34,35,36. The absorbance peaks at 1699 and 1636 cm–1 for the CO2-adsorbed CaO sample can be attributed to bridging carbonate stretching and asymmetric CO3 stretching vibrations [νas(CO3)] of the bicarbonate species, respectively. The broad structureless absorbance peaks between 1480 and 1318 cm–1 can be attributed to the symmetric and asymmetric CO3 stretching of unidentate carbonate, as well as the symmetric CO3 stretching [νs(CO3)] of bicarbonate37,38,39,40,41. When the Ga2O3 surface was modified with a small amount of Ca species, absorbance peaks attributable to CO2 adsorption by both Ga2O3 and CaO were observed after CO2 was introduced into the Ga2O3_Ca_1.1 sample. However, when the Ga2O3 surface was modified with large amounts of Ca species, the absorbance peaks attributed to CO2 adsorption on Ga2O3 had low intensity and mainly corresponded to the broad peaks derived from the adsorption of CO2 on CaGa4O7. Supplementary Fig. 5 shows the FTIR spectra of CO2-adsorbed Ga2O3, Ga2O3_Ca_1.1, Ga2O3_Ca_3.3, and CaGa4O7 samples after introducing the same amount of CO2 at various pressures in the 0.1–40.0 Torr range. CO2 was adsorbed significantly more on the Ga2O3_Ca_1.1 surface than on the Ga2O3 surface due to its adsorption at both Ga and Ca sites. However, the CaGa4O7 surface was not conducive to CO2 adsorption; therefore, CO2 adsorbed less onto the Ga2O3_Ca_3.3 surface than the Ga2O3_Ca_1.1 surface.

Figure 4 shows the FTIR spectra of the adsorbed CO2 species on Ga2O3_Ca_1.1 after different durations of photoirradiation. As the photoirradiation time increased from 0 to 106 h, the bands at 1225 [δ(OH)-Ga] and 1408 cm–1 [νs(CO3)-Ca] decreased and vanished after 104 h. At the same time, new bands gradually appeared at 1581, 1388, and 1353 cm–1 (asymmetric CO2 stretching [νas(CO2)], CH deformation [δ(CH)], and symmetric CO2 stretching [νs(CO2)] assigned to formate species (HCOO–Ga/Ca), respectively)34,35,36. As the photoirradiation continued, the formate species were consumed and gaseous CO (fundamental vibration band at 2143 cm−1)42 was formed simultaneously. This result indicates that the bicarbonate species is the intermediate during the photocatalytic conversion of CO2, and the formates transform into CO with photoirradiation, which is consistent with our previous results43,44. It is worth mentioning that in addition to the presence of intermediate species on the Ga2O3 surface ([δ(OH)–Ga]), the modification by Ca species further increased the amount of intermediate on Ga2O3_Ca_1.1. As the photocatalytic conversion of H+ into H2 and the conversion of CO2 into CO are two competing processes in an aqueous solution, the high adsorption of CO2 at the base site leads to high photocatalytic activity and selectivity toward CO evolution during the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 by H2O.

In order to demonstrate that the presence of CaO on the Ga2O3 surface enhances the photocatalytic activity and selectivity during the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 into CO, we investigated the photocatalytic performance during the conversion of CO2 by H2O over various Ag@Cr/CaO/Ga2O3 photocatalysts, the results of which are shown in Fig. 5. We found that the Ag@Cr/Ga2O3_Ca_1.1 photocatalyst (with a low amount of CaO generated on the Ga2O3 surface) significantly enhanced the rate of CO formation during the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 by H2O compared with bare Ag@Cr/Ga2O3 (Fig. 5a, b). However, no significant change in the rate of CO formation and selectivity toward CO evolution was observed for the sample labeled “Ag@Cr/(1.1 mol%CaO/Ga2O3)” (in which 1.1 mol% CaO was physically loaded onto Ga2O3 by grinding before loading Ag@Cr cocatalyst onto the CaO/Ga2O3 surface) as compared to bare Ga2O3 (Fig. 5c). Because uncalcined CaO-loaded Ga2O3 easily dissolves in H2O, we increased the CaO loading on the Ga2O3 surface to 30 mol% using the same grinding method (labeled “Ag@Cr/(30 mol%CaO/Ga2O3)”), which resulted in an increased rate of CO formation and a decrease in H2 formation (Fig. 5d). However, no improvement in photocatalytic activity and selectivity was observed when 30 mol% CaO was mixed with the prepared Ag@Cr/Ga2O3 and ground together (Fig. 5e) or when they were directly mixed in the reaction solution (Fig. 5f). These results clearly reveal that the addition of CaO on the Ga2O3 surface enhances the rate of CO formation and suppresses that of H2 during the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 by H2O. In addition, the tight junction between Ga2O3, CaO, and the Ag@Cr cocatalyst is crucial for the superior photocatalytic activity and selectivity of the photocatalyst for the conversion of CO2 into CO. In our previous work, we confirmed that Ag acts as an active site while the Cr(OH)3·H2O layer exterior to the Ag core increases CO2 adsorption30,31. Hence, the Ag@Cr cocatalyst should be loaded at the CaO/Ga2O3 interface in order to facilitate contact between the CaO-adsorbed CO2 species and the Ag active sites.

Rates of formation of H2 (blue bars), O2 (green bars), and CO (red bars), as well as selectivity toward CO evolution (black diamonds) for various photocatalysts: a Ag@Cr/Ga2O3; b Ag@Cr/Ga2O3_Ca_1.1; c Ag@Cr/(1.1 mol%CaO/Ga2O3), namely Ga2O3 physically mixed with 1.1 mol% of CaO by grinding before loading the Ag@Cr cocatalyst; d Ag@Cr/(30 mol%CaO/Ga2O3), which is similar to c except for using 30 mol% of CaO; e Ag@Cr/Ga2O3 + 30 mol%CaO, namely Ag@Cr/Ga2O3 physically mixed with 30 mol% of CaO by grinding; and f Ag@Cr/Ga2O3 and 30 mol% of CaO without mixing before adding into the reaction solution. Schematic structures of the photocatalysts are shown at bottom. Photocatalyst powder: 0.5 g, reaction solution volume: 1.0 L, additive: 0.1 M NaHCO3, CO2 flow rate: 30 mL min−1, light source: 400 W high-pressure Hg lamp.

Notably, although CaGa4O7 exhibited high selectivity toward H2 evolution, the H2 formation rate for CaGa4O7 was significantly lower than that for Ga2O3_Ca_3.3 (for the product formation rates over Ag-Cr/Ga2O3_Ca_3.3 see Supplementary Fig. 6). This indicates that the presence of CaGa4O7 on the Ga2O3 surface enhances the overall photocatalytic efficiency during the photocatalytic reaction, including CO2 conversion and water splitting. The Mott–Schottky plot (Supplementary Fig. 7) and the absorption spectra converted from the diffuse reflectance spectra using the Kubelka–Munk equation (Supplementary Fig. 8) enabled us to estimate the conduction band (CB) and valence band (VB) positions of Ga2O3, Ga2O3_Ca_0.62, and CaGa2O7, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. Since the CB and VB of Ga2O3 are both more positive than those of CaGa4O7, a heterojunction system between Ga2O3 and CaGa4O7 can be formed that greatly improves the spatial separation efficiency of the photogenerated carriers45. Therefore, CaGa4O7/Ga2O3 exhibited a much higher photocatalytic efficiency than bare Ga2O3 and CaGa4O7.

We expect that by exploiting the high CO2 adsorption of CaO and the high photocatalytic efficiency of CaGa4O7/Ga2O3, we can further improve the photocatalytic activity and selectivity of the photocatalyst to maximize the conversion of CO2 into CO by H2O. Figure 6a shows the formation rates of H2, O2, and CO during the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 by H2O for the Ga2O3_Ca_3.3 photocatalyst physically mixed with 30 mol% of CaO and Ag@Cr as the cocatalyst. As indicated, a high formation rate of CO (>835 µmol h–1) was achieved, in addition to an excellent selectivity toward CO evolution (>95%), with a stoichiometric amount of evolved O2. Both 12CO and 13CO were detected using quadrupole mass spectrometry (MS), and the peaks at m/z = 28 and m/z = 29 were located at the same positions as those detected by gas chromatography (GC) during the photocatalytic conversion of 13CO2 (for the isotopic lead experiments see Supplementary Fig. 10). Indeed, our results indicate that the detected 12CO was produced from the reduction of 12CO2 derived from the NaHCO3 additive in the solution43. As shown in Fig. 6b, with the consumption of 12CO2 derived from NaHCO3, the amount of generated 12CO gradually decreased, while the 13CO content increased under continuous bubbling of 13CO2. The total amounts of 13CO and 12CO detected by MS were consistent with the amount of CO detected by GC (Fig. 6c), which indicates that the CO was generated as the reduction product of either CO2 introduced in the gas phase or from NaHCO3, rather than from any organic contaminants on the photocatalyst surface. The converted concentration of CO based on the CO formation rate was found to be 11,531 ppm, indicating that ~1.2% of CO2 in the gas phase was transformed into CO (see Supplementary Information for the calculation details. The actual amounts of CO detected are shown in Supplementary Movie 1).

a Formation rates of H2 (blue triangles), O2 (green squares), and CO (red circles), and selectivity toward CO evolution (black diamonds) for the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 by H2O; b 12CO and 13CO detected by MS (m/z = 28 and 29) from the photocatalytic conversion of 13CO2 by H2O; c CO time-course as determined by MS (red squares) and GC (blue diamonds) for the photocatalytic conversion of 13CO2 by H2O.

In our previous work, we had found that basic oxides and hydroxides such as Cr(OH)331, SrO44, and rare earth (RE) hydrates and oxides28 function as good CO2 storage materials by generating the corresponding (hydroxy)carbonate compounds (e.g., Cr(OH)x(CO3)y and RE2(OH)2(3−x)(CO3)x), and they improve the photocatalytic activity and selectivity toward CO evolution. Now, we propose a possible mechanism for the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 by H2O over Ag@Cr/CaO/CaGa2O7/Ga2O3, as shown in Fig. 7. During the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 in an aqueous solution of NaHCO3, the Cr(OH)3·H2O and CaO species that are in close contact with Ag particles easily form (hydroxy)carbonate species (named M(OH)x(CO3)y, M=Cr or Ca)31, which greatly increase the concentration of CO2-related species around the Ag active sites, thereby improving selectivity for the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 into CO instead of water splitting. On the other hand, the Ga2O3/CaGa4O7 heterojunction improves the efficiency for spatial separation of the photogenerated carriers, which also increases the photocatalytic activity for the conversion of CO2 into CO. Moreover, while the Cr(OH)3·xH2O shell outside the Ag particle can be oxidized to Cr6+ and dissolve into the solution during the photocatalytic conversion of CO246, the presence of CaO around the Ag active site compensates for the reduced activity from the dissolution of Cr species. As a result, Ag@Cr/Ga2O3_Ca is photocatalytically much more stable than Ag@Cr/Ga2O3.

Herein, we reported the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 using a Ag@Cr/CaO/CaGa4O7/Ga2O3 photocatalyst, in which a satisfactory CO formation rate (>835 µmol h−1) and an excellent selectivity toward CO evolution (95%) were achieved with the stoichiometric production of O2 as the oxidation product of H2O. Through the use of various characterization techniques, we found that the CaO and CaGa4O7 formed on the Ga2O3 surface improved the adsorption of CO2 at basic sites in addition to enhancing the total photocatalytic efficiency. In addition, the physical mixing of CaGa4O7/Ga2O3 with CaO was a particularly simple and convenient technique for exploiting the high CO2 adsorption ability of CaO and the high photocatalytic efficiency of CaGa4O7/Ga2O3. These results are of particular interest, considering that previously, only insufficient amounts of CO2 reduction products were produced during artificial photosynthesis.

Methods

Ca-modified Ga2O3 (Ga2O3_Ca) was prepared using the ammonia precipitation method reported by Sakata et al.47. In this method, Ga(NO3)3∙nH2O (12.6 g) was dissolved in 200 mL of deionized water or CaCl2 solution in ultrapure water at various concentrations. Hydroxylation was carried out by dripping an ammonium hydroxide solution until the pH level reached 9.1. The obtained hydroxides were centrifuged and dried overnight. The Ga2O3_Ca sample was obtained by calcining the precursor at 1273 K for 10 h. Ag@Cr/Ga2O3_Ca was synthesized using the photodeposition method reported in our previous work30. In this method, the as-prepared Ga2O3_Ca powder (1.0 g) was dispersed in ultrapure water (1.0 L) containing the necessary amounts of silver nitrate (AgNO3) and chromium (III) nitrate (Cr(NO3)3). The suspension was purged with Ar gas and irradiated under a 400 W high-pressure Hg lamp with Ar gas flowing for 1.0 h, followed by filtration and drying at room temperature (~298 K). The Ag/Ga and Cr/Ga molar ratios were both 1.0 mol%.

Characterization

The as-prepared Ga2O3_Ca samples were characterized using the following techniques: XRD (Model: Multiflex, Rigaku Corporation, Japan) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.154 nm); XPS (Model: ESCA 3400, Shimadzu Corporation, Japan) with Mg Kα radiation; SEM (Model: SU-8220, Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Japan); TEM (Model: JEM-2100F, JEOL Ltd, Japan); and UV–Visible spectroscopy (V-650, JASCO) with an integrated sphere accessory. The BET surface areas of the photocatalyst samples were determined from their N2-adsorption isotherms at 77 K using a volumetric gas-adsorption measuring instrument (Model: BELSORP-miniII, MicrotracBEL Corp. (formerly BEL Japan, Inc.), Japan). Prior to these measurements, each sample was evacuated at 473 K for 1 h using a sample pretreatment system (Model: BELPREP-vacII, MicrotracBEL Corp. (formerly BEL Japan, Inc.), Japan). ICP-OES (Model: iCAP7400, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was used to determine the actual amounts of Ca modified on the Ga2O3 surface. The FTIR spectra of the adsorbed carbon species were recorded using an FTIR spectrometer (Model: FT/IR-4700, JASCO International Co., Ltd., Japan) equipped with a mercury–cadmium–tellurium (MCT) detector and cooled with liquid N2 in the transmission mode at 303 K. Each sample (~30 mg) was pressed into a wafer (diameter: 10 mm) and introduced into the instrument in a cylindrical glass cell with calcium fluoride (CaF2) windows. The wafer was evacuated at 673 K for 30 min before being examined, followed by treatment with O2 at ~40 Torr for 30 min, after which the wafer was evacuated for 30 min and cooled to 303 K. The data for each FTIR spectrum were obtained from 128 scans with a resolution of 4 cm−1. The energy gap of the band structure and flat band potential of the Ga2O3_Ca samples were determined using the Davis–Mott and Mott–Schottky equations, respectively; the experimental details are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Photocatalytic reaction

The photocatalytic reduction of CO2 was carried out using a flow system with an inner irradiation-type reaction vessel. The synthesized photocatalyst (0.5 g) was dispersed in ultrapure water (1.0 L) containing 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3). The CO2 was bubbled into the solution at a flow rate of 30 mL min−1. The suspension was illuminated using a 400 W high-pressure Hg lamp with a quartz filter, and the assembly was connected to a water-cooling system. The amounts of evolved H2 and O2 were detected using a gas chromatography system fitted with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD-GC, Model: GC-8A, Shimadzu Corporation, Japan) and a 5A molecular sieve (MS 5A) column, and Ar was used as the carrier gas. The amount of evolved CO was analyzed using a gas chromatography system fitted with a flame ionization detector (FID-GC, Model: GC-8A, Shimadzu Corporation, Japan), a methanizer, and a ShinCarbon ST column, and N2 was used as the carrier gas. High-performance liquid chromatography (Model: LC-4000, JASCO, USA) was used to detect the presence of liquid products.

In the isotope experiment, 12CO2 was replaced by 13CO2. The formation rates of H2, O2, 12CO, and 13CO under photoirradiation were detected using a quadrupole mass spectrometer (BELMASS, Microtrac BEL) combined with a TCD-GC detector.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the [figshare] repository, [https://figshare.com/s/84a5d675a273e507fb55 and/or https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12927422].

References

IPCC; Pachauri, R. K. & Meyer, L. A., eds. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (IPCC, Geneva, 2014).

Halmann, M. Photoelectrochemical reduction of aqueous carbon dioxide on p-type gallium phosphide in liquid junction solar cells. Nature 275, 115–116 (1978).

Inoue, T., Fujishima, A., Konishi, S. & Honda, K. Photoelectrocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide in aqueous suspensions of semiconductor powders. Nature 277, 637–638 (1979).

Li, K., Peng, B. & Peng, T. Recent advances in heterogeneous photocatalytic CO2 conversion to solar fuels. ACS Catal. 6, 7485–7527 (2016).

Mikkelsen, M., Jørgensen, M. & Krebs, F. C. The teraton challenge. A review of fixation and transformation of carbon dioxide. Energy Environ. Sci. 3, 43–81 (2010).

Barber, J. Photosynthetic energy conversion: natural and artificial. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 185–196 (2009).

Cokoja, M., Bruckmeier, C., Rieger, B., Herrmann, W. A. & Kühn, F. E. Transformation of carbon dioxide with homogeneous transition-metal catalysts: a molecular solution to a global challenge? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 8510–8537 (2011).

Wu, L. Y. et al. Encapsulating perovskite quantum dots in iron-based metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) for efficient photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 9491–9495 (2019).

Tu, W., Zhou, Y. & Zou, Z. Photocatalytic conversion of CO2 into renewable hydrocarbon fuels: state-of-the-art accomplishment, challenges, and prospects. Adv. Mater. 26, 4607–4626 (2014).

Linsebigler, A. L., Lu, G. & Yates, J. T. Jr Photocatalysis on TiO2 surfaces: principles, mechanisms, and selected results. Chem. Rev. 95, 735–758 (1995).

Vu, N.-N., Kaliaguine, S. & Do, T.-O. Critical aspects and recent advances in structural engineering of photocatalysts for sunlight-driven photocatalytic reduction of CO2 into fuels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1901825 (2019).

Stöcker, M. Methanol-to-hydrocarbons: catalytic materials and their behavior. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 29, 3–48 (1999).

Tian, P., Wei, Y., Ye, M. & Liu, Z. Methanol to olefins (MTO): from fundamentals to commercialization. ACS Catal. 5, 1922–1938 (2015).

Khodakov, A. Y., Chu, W. & Fongarland, P. Advances in the development of novel cobalt Fischer−Tropsch catalysts for synthesis of long-chain hydrocarbons and clean fuels. Chem. Rev. 107, 1692–1744 (2007).

Dry, M. E. The Fischer–Tropsch process: 1950–2000. Catal. Today 71, 227–241 (2002).

White, J. L. et al. Light-driven heterogeneous reduction of carbon dioxide: photocatalysts and photoelectrodes. Chem. Rev. 115, 12888–12935 (2015).

Surdhar, P. S., Mezyk, S. P. & Armstrong, D. A. Reduction potential of the carboxyl radical anion in aqueous solutions. J. Phys. Chem. 93, 3360–3363 (1989).

Hisatomi, T., Kubota, J. & Domen, K. Recent advances in semiconductors for photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 7520–7535 (2014).

Morris, A. J., McGibbon, R. T. & Bocarsly, A. B. Electrocatalytic carbon dioxide activation: the rate-determining step of pyridinium-catalyzed CO2 reduction. ChemSusChem 4, 191–196 (2011).

Iizuka, K., Wato, T., Miseki, Y., Saito, K. & Kudo, A. Photocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide over Ag cocatalyst-loaded ALa4Ti4O15 (A = Ca, Sr, and Ba) using water as a reducing reagent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 20863–20868 (2011).

Nakanishi, H., Iizuka, K., Takayama, T., Iwase, A. & Kudo, A. Highly active NaTaO3-based photocatalysts for CO2 reduction to form CO using water as the electron donor. ChemSusChem 10, 112–118 (2017).

Yoshida, H. et al. Calcium titanate photocatalyst prepared by a flux method for reduction of carbon dioxide with water. Catal. Today 251, 132–139 (2015).

Huang, Z., Teramura, K., Hosokawa, S. & Tanaka, T. Fabrication of well-shaped Sr2KTa5O15 nanorods with a tetragonal tungsten bronze structure by a flux method for artificial photosynthesis. Appl. Catal. B 199, 272–281 (2016).

Pang, R., Teramura, K., Asakura, H., Hosokawa, S. & Tanaka, T. Highly selective photocatalytic conversion of CO2 by water over Ag-loaded SrNb2O6 nanorods. Appl. Catal. B 218, 770–778 (2017).

Bhugun, I., Lexa, D. & Savéant, J.-M. Catalysis of the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide by iron (0) porphyrins. Synergistic effect of Lewis acid cations. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 19981–19985 (1996).

Meng, X. et al. Photocatalytic CO2 conversion over alkali modified TiO2 without loading noble metal cocatalyst. Chem. Commun. 50, 11517–11519 (2014).

Liao, Y. et al. Efficient CO2 capture and photoreduction by amine-functionalized TiO2. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 10220–10222 (2014).

Huang, Z., Teramura, K., Asakura, H., Hosokawa, S. & Tanaka, T. CO2 capture, storage, and conversion using a praseodymium-modified Ga2O3 photocatalyst. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 19351–19357 (2017).

Teramura, K., Tatsumi, H., Wang, Z., Hosokawa, S. & Tanaka, T. Photocatalytic conversion of CO2 by H2O over Ag-loaded SrO-modified Ta2O5. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 88, 431–437 (2015).

Pang, R. et al. Modification of Ga2O3 by an Ag–Cr core–shell cocatalyst enhances photocatalytic CO evolution for the conversion of CO2 by H2O. Chem. Commun. 54, 1053–1056 (2018).

Pang, R., Teramura, K., Asakura, H., Hosokawa, S. & Tanaka, T. Effect of thickness of chromium hydroxide layer on Ag cocatalyst surface for highly selective photocatalytic conversion of CO2 by H2O. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 2083–2090 (2018).

Ogata, M., Fujimoto, K. & Shinkai, S. Molecular design of calix[4]arene-based extractants which show high Ca2+ selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 4505–4506 (1994).

Moriga, T., Kammler, D. R., Mason, T. O., Palmer, G. B. & Poeppelmeier, K. R. Electrical and optical properties of transparent conducting homologous compounds in the indium–gallium–zinc oxide system. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 82, 2705–2710 (1999).

Tsuneoka, H., Teramura, K., Shishido, T. & Tanaka, T. Adsorbed species of CO2 and H2 on Ga2O3 for the photocatalytic reduction of CO2. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 8892–8898 (2010).

Collins, S. E., Baltanás, M. A. & Bonivardi, A. L. An infrared study of the intermediates of methanol synthesis from carbon dioxide over Pd/β-Ga2O3. J. Catal. 226, 410–421 (2004).

Collins, S. E., Baltanás, M. A. & Bonivardi, A. L. Infrared spectroscopic study of the carbon dioxide adsorption on the surface of Ga2O3 polymorphs. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 5498–5507 (2006).

Fukuda, Y. & Tanabe, K. Infrared study of carbon dioxide adsorbed on magnesium and calcium oxides. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 46, 1616–1619 (1973).

Philipp, R. & Fujimoto, K. FTIR spectroscopic study of carbon dioxide adsorption/desorption on magnesia/calcium oxide catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. 96, 9035–9038 (1992).

Busca, G. & Lorenzelli, V. Infrared spectroscopic identification of species arising from reactive adsorption of carbon oxides on metal oxide surfaces. Mater. Chem. 7, 89–126 (1982).

Tsyganenko, A. & Filimonov, V. Infrared spectra of surface hydroxyl groups and crystalline structure of oxides. J. Mol. Struct. 19, 579–589 (1973).

Busca, G., Lamotte, J., Lavalley, J. C. & Lorenzelli, V. FT-IR study of the adsorption and transformation of formaldehyde on oxide surfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 109, 5197–5202 (1987).

Wenig, R. W. & Schrader, G. L. In situ FTIR (Fourier transform IR) spectroscopy of 1-butene and 1, 3-butadiene. Selective oxidation to maleic anhydride on vanadium-phosphorus-oxygen catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. 91, 1911–1918 (1987).

Teramura, K. et al. Which is an intermediate species for photocatalytic conversion of CO2 by H2O as the electron donor: CO2 molecule, carbonic acid, bicarbonate, or carbonate ions? J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 8711–8721 (2017).

Yoshizawa, S. et al. Important role of strontium atom on the surface of Sr2KTa5O15 with a tetragonal tungsten bronze structure to improve adsorption of CO2 for photocatalytic conversion of CO2 by H2O. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 37875–37884 (2019).

Habisreutinger, S. N., Schmidt‐Mende, L. & Stolarczyk, J. K. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 on TiO2 and other semiconductors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 7372–7408 (2013).

Pang, R., Teramura, K., Asakura, H., Hosokawa, S. & Tanaka, T. Effect of Cr species on photocatalytic stability during the conversion of CO2 by H2O. J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 2894–2899 (2019).

Sakata, Y., Hayashi, T., Yasunaga, R., Yanaga, N. & Imamura, H. Remarkably high apparent quantum yield of the overall photocatalytic H2O splitting achieved by utilizing Zn ion added Ga2O3 prepared using dilute CaCl2 solution. Chem. Commun. 51, 12935–12938 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This study was partially supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas, “All Nippon Artificial Photosynthesis Project for Living Earth” [grant number 2406] of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) of Japan and the Program for Element Strategy Initiative for Catalysts & Batteries (ESICB) [No. JPMXP0112101003], commissioned by the MEXT of Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.P. and K.T. designed the research. R.P. prepared the photocatalyst powder and conducted XRD, BET, XPS, SEM, TEM, ICP-OES, UV–Vis, and FTIR studies, electrochemical measurements, and the photocatalytic CO2-conversion experiments. M.M. carried out the isotopic labeling experiment. R.P., K.T., M.M., H.A., S.H., and T.T. discussed the results. R.P. and K.T. wrote the manuscript with contributions from the other authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pang, R., Teramura, K., Morishita, M. et al. Enhanced CO evolution for photocatalytic conversion of CO2 by H2O over Ca modified Ga2O3. Commun Chem 3, 137 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-020-00381-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-020-00381-2

This article is cited by

-

Fe-modified hydroxyl-rich structured Pt/Fex/γ-Al2O3/Al catalyst for CO oxidation at room temperature: behavior and mechanism

Reaction Kinetics, Mechanisms and Catalysis (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.