Abstract

Ocean deoxygenation driven by global warming and eutrophication is a primary concern for marine life. Resistant animals may be present in dead zone sediments, however there is lack of information on their diversity and metabolism. Here we combined geochemistry, microscopy, and RNA-seq for estimating taxonomy and functionality of micrometazoans along an oxygen gradient in the largest dead zone in the world. Nematodes are metabolically active at oxygen concentrations below 1.8 µmol L−1, and their diversity and community structure are different between low oxygen areas. This is likely due to toxic hydrogen sulfide and its potential to be oxidized by oxygen or nitrate. Zooplankton resting stages dominate the metazoan community, and these populations possibly use cytochrome c oxidase as an oxygen sensor to exit dormancy. Our study sheds light on mechanisms of animal adaptation to extreme environments. These biological resources can be essential for recolonization of dead zones when oxygen conditions improve.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The constant increase in global use of fertilizers and discharges of nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) is causing drastic changes to ocean biogeochemistry and increasing vulnerability of aquatic environments1,2. Nutrient-driven eutrophication is increasing not only along the coast, but also in otherwise nutrient-deficient open waters, fueling aquatic primary production worldwide1. Scarce water circulation and high rates of degradation can eventually lead to water column hypoxia (≤63 µmol O2 L−1 or ≤2 mg O2 L−1) and anoxia (undetectable oxygen)3. This phenomenon, ocean deoxygenation, is further enhanced by global warming as higher water temperatures stimulate metabolic processes and decrease oxygen solubility4. Oceanic models anticipate a global decrease in the total oxygen inventory of up to 7% by 2100, with a number of oxygen minimum zones (OMZs) losing more than 4% oxygen per decade5.

Anoxia in pelagic and benthic environments can be temporal and last minutes to hours as in the case of intertidal mud flats. Invertebrates can cope with these short-term events by activating anaerobic energy metabolism6. Anoxia, however, can persist for hundreds to thousands of years as in the case of certain stagnant bottom water of enclosed seas such as the Baltic and Black Seas3,7. In these systems, bottom water close to the seafloors is regularly characterized by very low oxygen (≤22 µmol O2 L−1), which precludes life to most animals7. These marine systems characterized by severe hypoxia or anoxia are often referred as dead zones7. While the term dead zone gives an idea of an ecosystem without life, it was shown that the core of large oceanic OMZs, where fish, macro-, and megafauna are absent, hosts relatively large abundances of protists and micrometazoans6.

Many pelagic zooplankton organisms have benthic stages and can survive hypoxic/anoxic conditions in the form of resting eggs8,9; such eggs have been shown to hatch once oxygen returns10. However, some eukaryotic organisms are adapted to live in anoxia, which may be due to the presence of copious organic matter and low predation pressure6,11. Nematodes are among the most abundant animals in these regions12,13,14, and have evolved strategies to cope with low oxygen conditions15,16. However, adaptation and community responses of benthic organisms to oxygen starvation have only recently started to be investigated6,17, and the mechanism through which they survive long-term anoxia is one of the most intriguing questions in marine ecology.

Marine OMZs are oxygen limited, but only occasionally become euxinic (i.e., both absent in oxygen and rich in sulfide), except in rare cases when sulfate reduction becomes important under nitrate-limited conditions18. Enclosed marine basins (e.g., Baltic and Black Seas), receiving high loads of organic matter and with euxinic waters, host microbial communities largely thriving on sulfur metabolism19. These areas are considered inhospitable to aerobically respiring organisms, as the main product of sulfate reduction, i.e., hydrogen sulfide (H2S), is toxic to aquatic life. Free H2S can lead to respiratory stress to benthic organisms already at micromolar concentrations20, and at ca. 14 µmol L−1, H2S effects on marine benthic organisms at a population level start arising21. However, certain aerobic organisms, including nematodes, gastrotrichs, and gnathostomulids, can live in sulfidic sediments22. Several nematode species can detoxify from sulfides by creating a viscous shield consisting of elemental sulfur in the epidermis13,23. Other nematode species live in symbiosis with sulfide-oxidizing bacteria, which may protect them from sulfide24. Under anoxic conditions and when nitrate is present, such bacteria are known to couple sulfide oxidation with nitrate reduction25,26, and this process may yield oxidized nitrogen compounds such as nitrous oxide (N2O)25,26. N2O has therefore been shown to be a good indicator of potential nitrate reduction at the oxic–anoxic interface of the Baltic Sea dead zone27. While microbial ecology studies in euxinic systems proliferate, there is a large knowledge gap concerning species diversity and potential metabolism of multicellular anaerobic eukaryotes. To our knowledge, there are no studies using RNA sequencing to analyze both rRNA and mRNA to investigate dead zone animals.

This study aimed to use molecular data to advance our understanding of micrometazoan diversity and metabolism in low oxygen and sulfidic environments. Specifically, we hypothesized that (1) low oxygen and high sulfide concentrations reduce metazoan diversity and alter community structure, and (2) mRNA transcripts translating for metazoan proteins in dead zone sediments (DZS) are significantly different (in amount and function) in response to oxygen, nitrous oxide, and sulfide concentrations. To tackle these hypothesis, we conducted a sampling campaign in the central Baltic Sea (Fig. 1), the largest dead zone in the world7. We analyzed sediments with conditions of normoxia (>300 µmol L−1 O2), severe hypoxia (ca. 10 µmol L−1 O2), severe hypoxia/anoxia (0‒5 µmol L−1 O2), and complete anoxia (0 µmol L−1 O2). These DZS presented different availability of oxidized nitrogen (i.e., N2O) and H2S.

Sediment cores and water samples were collected in April 2018 from each station indicated in the map. Sediments were either sectioned (0–2 cm sediment layer) for later molecular and microscopy analyses or kept intact and microprofiled onboard for porewater chemistry. Station A is 60-m deep and permanently oxygenated; Station D is 130-m deep and strictly hypoxic and sulfidic; Station E is 170-m deep, anoxic with N2O; Station F is 210-m deep and anoxic.

Here we show that DZS contain animal life adapted to cope with these harsh conditions. Alpha diversity and community structure based on rRNA data, differs significantly among anoxic and euxinic sites. Our results indicate that zooplanktons are present as resting stages in DZS, and the mRNA data suggest that these organisms use the enzyme cytochrome c oxidase (COX) as an oxygen sensor, which has previously been shown in, e.g., yeast28. In addition, nematodes can persist in anoxic and sulfidic sediments in niches like sulfide oxidation zones, or in low abundance potentially with a downregulated metabolism. To our knowledge, this is the first study using a comprehensive molecular dataset to study animals in dead zones. The findings imply that even on a low molecular level, dead zones might not be as dead as the terminology implies.

Results

Chemical environment characterization

Water column profiles: The measured oxygen concentration in the water column was high (>400 µmol L−1) vertically in the water column profile at Station A (Fig. 1). At the other three stations, the onset of a chemocline caused a sharp decrease in O2 concentration between 65- and 70-m depth (Fig. 2). At 100-m depth, we recorded an oxygen pocket at stations D–F with concentrations 18‒25 µmol L−1 (Fig. 2). At stations D and E, traces of O2 (<10 µmol L−1) were detectable in the bottom water, whereas station F had bottom water anoxia (Fig. 2). N2O did not show any trend at A, while it clearly peaked at the depth of the oxygen pocket at the impacted stations. At station F, below the peak, N2O decreased monotonically with depth, whereas it showed a slight increase in concentrations at station E in proximity of the bottom.

Top four panels: vertical concentration profiles of oxygen (O2) and nitrous oxide (N2O) in the water column at station A (a), station D (b), station E (c), and station F (d). Bottom four panels: concentration microprofiles of oxygen (O2), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), and nitrous oxide (N2O) in sediments of station A (e), station D (f), station E (g), and station F (h). Bold lines represent average microprofiles, and horizontal bars indicate standard error of the mean. The sediment–water interface is indicated by the horizontal dotted lines.

Sediment microprofiles: Porewater microprofile measurements showed that O2 was present at high concentrations (>300 µmol L−1) at the sediment–water interface at station A (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Hypoxic conditions (8.8 µmol L−1) and almost anoxic conditions (1.8 µmol L−1) were recorded at the sediment–water interface at stations D and E, respectively. No O2 was measured at station F. It cannot be excluded that minimal O2 contamination happened during sampling and microprofiling at station E, although great care was taken to mimic in situ conditions. O2 correlated negatively with H2S (rho = −0.78, P < 0.001) and positively with N2O (rho = 0.44, P < 0.001) in the measured sediment cores (tested for the whole dataset from all stations, Spearman correlations, Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

Oxygen penetrated into the sediment to 7.0, 1.4, and 0.7 mm at stations A, D, and E, respectively (Fig. 2). High N2O concentrations (471 nmol L−1) were recorded at the sediment–water interface at station E, where N2O penetrated to 3-mm depth (Fig. 2). Concentrations of N2O were two orders of magnitude lower at stations A (19 nmol L−1) and F (29 nmol L−1), and reached zero at 16- and 5-mm depth, respectively (Fig. 2). It was not possible to measure any N2O profile at station D. The highest porewater sulfide concentration was measured at station D (85 µmol L−1 H2S at 1-cm depth). At this station, sulfide reached the sediment–water interface determining a zone where both O2 and H2S were present (Fig. 2). At station E, H2S appeared below the oxic zone at 2-mm depth and reached 21 µmol L−1 at 1-cm depth. At station F, H2S appeared at 0.8 mm, where 32 µmol H2S L−1 was recorded at 1-cm depth. At station A, H2S was close to zero all the way down to 1-cm depth (Fig. 2).

Metazoan diversity, community composition, and metabolism

Eukaryotic diversity and community composition: The alpha diversity of the eukaryotic community composition in the 0–2 cm sediment layer, based on active taxa (i.e., 18S rRNA sequences), was different between stations (n = 3 per station, Fig. 3a). Full data are available in Supplementary Data 2 (SILVA taxonomy classifications), Supplementary Data 3 (NCBI NT taxonomy classifications), and Supplementary Table 2 (alpha diversity indexes). In more detail, station A had a higher alpha diversity (7.51 ± 0.06 Shannon’s H) compared with the other stations (one-way ANOVA post hoc Tukey test, P < 0.01 for all tests, Fig. 3a). Furthermore, there was also a lower alpha diversity at stations D (5.03 ± 0.24 Shannon’s H) and F (4.85 ± 0.23, P < 0.01) when compared with E (5.60 ± 0.04, P < 0.05, Fig. 3a). Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analysis of eukaryotic beta diversity showed that the stations formed different clusters, especially station A (O2 rich and almost no H2S), compared with the hypoxic–anoxic stations that all had higher concentrations of sulfide, when tested for the presence/absence and the relative abundance (PERMANOVA, Sørensen index, and Bray–Curtis dissimilarity, F = 13.4 and F = 43.1, respectively, P < 0.01 for both tests; Sørensen Fig. 3b, and Bray–Curtis in Supplementary Fig. 1). In the same analysis, station E that had the highest concentration of N2O clustered differently when compared with the other hypoxic–anoxic stations D and F. See Supplementary Fig. 2 for an overview of all eukaryotic phyla detected in the samples.

a Boxplot graphs showing the alpha diversity (Shannon’s H) of the eukaryotic community in the top 2 cm sediment, based on the SILVA-classified RNA data (extracted 18S rRNA data, n = 3 biologically independent samples per site). Statistically significant differences are denoted, * (P < 0.05) and ** (P < 0.01) followed by sampling sites that were different. The center line in the boxes represents the median; top and bottom lines of the boxes show the first and third quartiles. The top and bottom whiskers show the maximum and minimum values, respectively. b NMDS of the Sørensen index based on the presence/absence of the SILVA-classified 18S rRNA eukaryotic community composition for RNA samples. The colors denote sediment samples from stations A (brown), D (gray), E (purple), and F (blue).

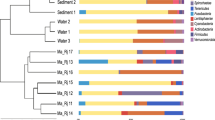

Looking closer at metazoan phyla, station A had a significantly higher relative abundance of Annelida (1.55 ± 0.91% in station A), Cnidaria (0.40 ± 0.03%), Kinorhyncha (0.49 ± 0.24%), Platyhelminthes (2.13 ± 0.61%), Priapulida (0.21 ± 0.03%), and Xenacoelomorpha (2.33 ± 0.47%) compared with the other stations (one-way ANOVA, post hoc Tukey test, all P < 0.05, Fig. 4a). In contrast, Arthropoda were significantly lower at station A compared with the other stations (12.09 ± 2.91% compared with stations D (38.47 ± 5.38%), E (30.13 ± 3.13%), and F (38.00 ± 2.97%), all P < 0.01, Fig. 4a). A similar pattern was observed for Rotifera, dominated by the class Monogononta, which had a higher relative abundance at stations D–F compared with A (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Data 2). The phylum Nematoda had the highest relative abundance at stations A and E. At station A, the relative abundance was 7.64 ± 0.55%, and was significantly higher compared with D (0.26 ± 0.05%) and F (0.46 ± 0.24%) (P < 0.01 for all tests, Fig. 4a). Similarly, station E also had a significantly higher relative abundance of Nematoda (5.43 ± 2.16%) compared with D and F (all P < 0.01, Fig. 4a). As Arthropoda, Rotifera, and Nematoda were the metazoan with the highest relative abundance in the sediment, data for these groups were analyzed further for community structure and metabolic functions.

a Metazoan 18S rRNA community composition in the sediment based on extracted 18S rRNA sequences from the RNA-seq (SILVA database). The heatmap shows taxonomy groups >0.01% (average of all samples). The colors denote relative abundance with white representing 0%, white–blue gradient 0–6%, blue–purple gradient medium 6–12%, and light purple–dark purple gradient 12–42%. b Relative abundance of Arthropoda classes/genera, and c Nematoda families/genera based on the RNA-seq 18S rRNA sequences classified against the NCBI NT database. The x axis shows the relative abundance (%) for the Arthropoda and Nematoda phyla. Bold text denotes genera with a high relative abundance, while stars denote taxonomic classifications that could not be assigned to a genus for specific classes or families. d RNA transcripts for Arthropoda and Nematoda that were successfully classified against the NCBI NR database. The y axis shows the sum of normalized read counts as counts per million sequences (CPM) of all eukaryotic taxa. Significant statistical differences between sites are denoted. * (P < 0.05) and ** (P < 0.01) followed by sampling sites that were different.

Arthropoda and Rotifera taxonomy and metabolism: There was a significantly larger relative abundance of the cladoceran genus Bosmina (class Branchiopoda, phylum Arthropoda) at stations D (68.7 ± 1.1% 18S rRNA of Arthropoda), E (67.4 ± 1.4%), and F (66.0 ± 3.0%) compared with A (9.3 ± 1.4%) (one-way ANOVA post hoc Tukey test, P < 0.01, Fig. 4b). The cladoceran genus Eubosmina (former genus name of Bosmina) also had significantly higher relative abundance at stations D–F (P < 0.01, Fig. 4b). Rotifera was dominated by the class Monogononta, and genera Synchaeta (no significant difference between stations in relative abundance), and a higher relative abundance of Keratella at E compared with stations A and D (P < 0.05, Supplementary Data 2).

RNA transcripts successfully classified against the NCBI NR database and related to Arthropoda taxonomy showed significantly lower number of database hits for station A when compared with D (one-way ANOVA, post hoc Tukey test, P < 0.05, Supplementary Data 4, Fig. 4d). Proteins affiliated with the family Bosminidae (including genera Bosmina and Eubosmina) at D–F were largely represented by aerobic respiration enzyme COX subunit I (IPR000883), and e.g., respiration chain enzyme NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 2 (IPR003917) and stress-related heat shock protein Hsp90 (IPR001404) (only four proteins affiliated for Bosminidae, Supplementary Table 3). Similarly, proteins affiliated with Rotifera at D–F were dominated by small heat shock protein HSP20 (IPR031107), COX subunit I (IPR000883), potassium channel inhibitor (IPR001947), and electron transport protein Cytochrome b (IPR030689) (17–134 proteins affiliated with Rotifera, Supplementary Table 4). These data indicate that Arthropoda and Rotifera animals were under stress in the hypoxic and anoxic sediments. The low molecular activity in the RNA transcript dataset suggests that these animals were surviving in resting stages (such as dormancy or eggs).

Nematoda taxonomy and metabolism: The 18S rRNA data for nematodes showed a high diversity of genera over several families (Fig. 4c). Alpha diversity for nematodes was higher at stations A, D, and F (Shannon’s H 4.1 ± 0.5) compared with station E (2.0 ± 0.5, one-way ANOVA post hoc Tukey test, P < 0.05, Supplementary Table 2). At station F, the genus Sabatieria had a significantly higher relative abundance compared with A (33.4 ± 21.3% compared with 0.1 ± 0.1%, respectively, P < 0.05, Fig. 4c). The genus Halomonhystera had a higher relative abundance at E (73.9 ± 9.3% compared with <10.5% for the other stations, P < 0.01 for all tests across stations, Fig. 4c). At station A, several genera belonging to different families had higher relative abundances compared with the other stations (e.g., families Axonolaimidae, Cyatholaimidae, Microlaimidae, and Xyalidae, P < 0.01 when tested for genera Axonolaimus, Cyatholaimus, Paracanthonchus, Calomicrolaimus, and Microlaimus, respectively, Fig. 4c). Unclassified nematode 18S rRNA sequences had a high relative abundance at station D compared with the other stations (P < 0.05, Fig. 4c).

RNA transcripts aligned against proteins in the NCBI NR database and linked to nematode taxonomy showed that station A had more database hits affiliated with nematodes (one-way ANOVA post hoc Tukey test, P < 0.01), as well as station E compared with D and F (P < 0.01, Fig. 4d). There were more proteins affiliated with Nematoda at A (310 ± 6 proteins, P < 0.01), followed by E (170 ± 45 proteins, P < 0.01). Stations D and F had a similar number of proteins (14 ± 6 and 21 ± 7, respectively) (Fig. 5). COX subunit I (IPR000883) had the highest counts per million sequence (CPM) values for all proteins at stations A and E, but was also present at D and F (Fig. 5). In stations D and F, the superfamily of proteolytic enzyme Peptidase C1A (IPR013128) had higher CPM values, as well as the Major facilitator superfamily (IPR002423), which includes proteins involved in membrane transport solutes (Fig. 5). Furthermore, the Chaperonin Cpn60/TCP-1 family (IPR002423) was higher at station D. Proteins involved in glycolysis included, e.g., pyruvate kinase and malate/L-lactate dehydrogenase, and these proteins were affiliated with nematodes in the hypoxic and anoxic sediments (stations D and E, Supplementary Data 4). Ribosomal proteins were available at all stations (Fig. 6). There was no detection of “transcription initiation” and “translation elongation factor” proteins at stations D and F, and the detection of RNA and DNA polymerases was also lower at the same stations (Fig. 6). In contrast, these essential proteins in gene transcription and protein translation were present at stations A and E (Fig. 6). Similarly, citrate synthase used in aerobic respiration was only detected at stations A and E (Supplementary Data 4).

Microscopy visual identification of DZS metazoan

In accordance with the molecular data, visual observation of samples confirmed the presence of a conspicuous number of Bosminidae-like resting stages in the anoxic sediment (Fig. 7a, see more photos in Supplementary Fig. 3). Microscopy analyses also confirmed the presence of nematodes Halomonhystera sp. (Fig. 7b), Sabatieria sp. (male Fig. 7c, female Fig. 7d, and juvenile Fig. 7e; Supplementary Fig. 4), and Linhomoeidae sp. (Fig. 7f).

a Bosminidae-like resting eggs. b Juvenile Halomonhystera with the inset showing a higher magnification of the buccal cavity (green frame). c Male Sabatieria sp. with the inset of buccal cavity (green) and copulatory spicules (blue). d Female Sabatieria sp. with the inset of buccal cavity (green). e Juvenile Sabatieria sp. f Juvenile Linhomoeidae with the inset of buccal cavity (green). Scale bars are 500 µm and 50 µm for insets.

Discussion

This study provides the first attempt to uncover metabolic pathways and diversity of active animals in DZS using up-to-date sequencing techniques29. Dead zone conditions—i.e., O2 concentration below 22 µmol L−1—generally lead to mass mortality of animals7. The investigated deeper stations D–F had euxinic waters for several years before the inflow of salty, oxygenated North Sea water (major Baltic inflow), which increased bottom water O2 levels to 10‒50 μM between June 2015 and January 201730. Since then, there were no more inflows. At the time of sampling, station F was anoxic (0 µmol L−1 O2), station E was anoxic to severely hypoxic (0‒5 µmol L−1 O2), and station D was severely hypoxic (7‒10 µmol L−1 O2). These sites have thus experienced dead zone conditions for at least 16 months continuously.

Nematodes had the highest diversity among metazoan taxa. In the sediment, organic material undergoes degradation and diagenesis26; thus, portions of the molecular data might derive from damaged ribosomes or degraded hereditary material. However, the presence of RNA transcripts (i.e., mRNA) strongly indicates that some nematode species were alive and metabolically active in this DZS. Nematodes are known to tolerate hypoxia15,31,32, and have been observed, e.g., in the Gulf of Mexico and Black Sea dead zones33,34,35. Benthic nematodes can temporarily cope with anoxia by migrating upward to the overlying oxic water until normoxic conditions return to the sediment32. However, at the sites here studied, 60–140-m migration would be extremely difficult to achieve, and would not explain why the nematodes were detected in the sediment. It is more likely that benthic nematodes were adapted and able to survive in the oxygen-deficient conditions. It has been proposed that the quantity of food for benthic fauna is usually high in oxygen-deficient zones, which together with complete absence of larger predators, would make these organic-rich sediments suitable for colonization of certain micrometazoans6. Nematodes are among the micrometazoan groups that have successfully evolved to cope with anoxia and sulfides23,24,36. For example, short time exposure to hypoxia (up to 7 days) had negligible effects on various nematode species37, while 14 days of anoxia decreased the general abundance, but species such as Sabatieria pulchra showed resistance38. Furthermore, Taheri et al.39 observed nematodes persisting in anoxic sediment after 307 days, including species belonging to the genus Sabatieria. Our results also showed that this genus was among the dominant nematodes at the hypoxic–anoxic stations in the 18S rRNA dataset, and found visually with microscopy.

Under such extreme conditions, certain nematodes are able to change to anaerobic metabolism (fermentation) or into a low metabolic state called cryptobiosis (reviewed in Tahseen40). Considering the lower number of sequences and the absence of essential enzymes for transcription and translation at stations D and F, it is possible that nematode communities at these stations consisted of low abundant taxa adapted or trying to survive in these extreme conditions. The strong difference in classified proteins further indicates that the metabolic activity was different at stations A and E compared with D and F. Furthermore, proteins affiliated with nematodes in the oxygen-deficient sediments, such as pyruvate kinase and malate/l-lactate dehydrogenase, were likely involved in anaerobic metabolisms41. Interestingly, citrate synthase was detected not only at the oxic station A, but also at the oxygen-deficient station E, which suggests that nematodes were able to use oxygen at extremely low concentrations. Previous studies have shown that as little as 17.6 µmol L−1 O2 can support aerobic respiration in nematodes from natural springs42. Our study indicates that nematodes might be able to respire aerobically at even lower oxygen concentrations (≤1.8 µmol L−1). Even though oxygen was present at station D, the nematode metabolic activity was lower than that at station A or E, which suggests that the high sulfide concentrations at station D might have had a detrimental effect on the nematode populations. However, nematode taxa belonging to the genus Sabatieria were found in the presence of high sulfide too, suggesting that these animals must have evolved efficient sulfide detoxification mechanisms40.

A striking pattern in our results was the high relative abundance of the genus Halomonhystera at station E also confirmed visually with microscopy. This genus has previously been reported from bacterial mats at 1280-m water depth in sulfide-rich sediments43. It is therefore likely that bacterial denitrification coupled to sulfide oxidation26 in the sediment at station E (as indicated by the clear overlap between the N2O and H2S profiles at 2‒3-mm depth) formed a niche habitat for Halomonhystera. The number of Nematoda taxa able to occupy such niche is small, which may also explain the lower diversity of nematodes at station E. Sulfide-oxidizing bacteria have previously been detected on nematode’s (Stilbonematinae) cuticle, and this ectosymbiosis likely helps to detoxify high levels of sulfide36,44. Other nematodes (Oncholaimidae) are non-symbiotic and show detoxification through secreting epidermis inclusions made of elemental sulfur23. Interestingly, nematodes also had the lowest diversity at station E, and this was possible due to a specific niche of survival in this sediment dominated by a few species such as Halomonhystera and Sabatieria.

In the hypoxic/anoxic sediments, a predominant portion of RNA transcripts, affiliated with pelagic taxa like Bosmina (formerly Eubosmina) and Rotifera, was attributed to COX subunit I. This protein can be used as an oxygen sensor as seen for mammalian tissue cells45 and yeast28. In addition, under anoxic conditions, COX functions as a nitrite reductase that produces nitric oxide in eukaryotic mitochondria46. The high number of 18S rRNA sequences and microscope observation of resting stages, but the limited number of RNA transcript-classified proteins detected for Bosmina, indicate that these populations consisted of resting eggs. Diapausing eggs of Bosmina have been found to be viable for 15‒21 years47, and possibly an egg bank in the sediment has accumulated over several years in the central Baltic Sea. Rotifer populations in the hypoxic/anoxic sediments had, in addition to COX subunit I, a major portion of the RNA transcripts attributed to the small heat shock protein HSP20. These shock proteins are upregulated in rotifer resting eggs48, and such eggs have been observed to be viable for up to 100 years47. Zooplankton egg banks (including rotifer) have previously been observed in Baltic Sea anoxic sediments, and these eggs hatched upon oxygenation10. Rotifers can tolerate low oxygen conditions49,50, and change to anaerobic metabolism during a few days up to a month51,52. Considering that there was a higher relative abundance of 18S rRNA sequences of rotifers at stations D–F compared with the oxic sediment at station A, it is likely that rotifer resting eggs were abundant and kept accumulating in the oxygen-deficient sediments, free from benthic predation, for a relatively long period of time. The enzyme citrate synthase—a proxy for aerobic metabolism53—was not present in either the Bosmina or Rotifera datasets at any station, further suggesting that these populations were dormant. Our results thus indicate that there is an available egg bank of zooplankton in sediments of the largest dead zones in the world. To our knowledge, this is the first study to indicate that dormant zooplankton uses COX subunit I as an oxygen sensor to cue for hatching.

To summarize, we have here shown that the diversity and community structure of metazoans in DZS are different between low oxygen areas, and that this is likely related to the concentration of sulfide in the sediment. Nematodes survive in specialized niches such as sulfide oxidation zones, or are in low abundance (potentially with a downregulated metabolism) in anoxic and sulfidic sediments. This was also indicated by the number of proteins classified to nematodes that were the highest in oxic and hypoxic sediments (sulfide oxidizing), when compared with sulfidic hypoxic and anoxic sediments. It has previously been shown that zooplankton eggs accumulate in anoxic sediment, and oxygen is a cue for hatching10. Our data further indicate that COX subunit I might be the key protein for sensing oxygen by the zooplanktonic dormant community. Reoxygenation of dead zones would therefore increase the flux of carbon to the water column, and thus enhance the benthic–pelagic coupling10. Moreover, nematode communities come back quickly after the onset of normoxia32,39,54, and would therefore increase the availability of food for recolonization of benthic communities. We conclude that animals are alive and adapted to survive in dead zones, and these biological resources are therefore not lost and could be important in the recovery of benthic metazoan communities if oxygen conditions improve.

Methods

Study area and sampling

The central Baltic Sea is characterized by permanent thermohaline stratification in its deeper basins27,55. Two large inflows of saline and oxygenated waters reached the inner Baltic Sea in 2003 and 2014, triggering oxidation processes in otherwise anoxic bottom waters. Oxygenation is however an ephemeral event in the Baltic as the inflow of denser water masses leads to even stronger stratification56. For this study, we visited four stations (A, D, E, F) along a gradient of depth and bottom water oxygen concentrations in April 2018 onboard of R/V Skagerak (Fig. 1). Station A is 60-m deep and permanently oxygenated (sampled April 25, long 19 °04′951, lat 57 °23′106); Station D is 130-m deep and strictly hypoxic (O2 ≤ 25 µmol L−1, sampled April 26, long 19°19′414, lat 57 °19′671); Station E is 170-m deep, anoxic, and nitrate-containing (sampled April 23, long 19°30′451, lat 57°07′518); Station F is 210-m deep, euxinic, and nitrate-free (sampled April 23, long 19°48′035, lat 57°17′225).

Water column oxygen profiles were measured by means of a CTD-rosette system (SBE 911plus, SeaBird Electronics, USA) equipped with O2 sensors (SBE 43 Dissolved O2 Sensor, SeaBird Electronics, USA). Water column sampling was carried out at different depths (n = 12) depending on the site water column height. The bottles from the CTD rosette were sampled immediately after withdrawal by means of a Viton© tubing, and subsamples for nitrous oxide (N2O) were collected in 12-mL Exetainers (Labco, UK). The water was allowed to overflow for at least three times the Exetainer volume, biological activity stopped with 100 µL of a 7 mol L−1 ZnCl2 solution, and Exetainers immediately closed air-tight, stored upside down and refrigerated until later analysis. Analysis of N2O was performed by the headspace technique on a gas chromatograph (SRI 8610C) equipped with an electron capture detector (ECD) using N2 as carrier gas.

Sediment was collected with a modified box corer, which allows sampling of undisturbed surfaces even in very soft and highly porous sediments57. Two to three box core casts were done at each station, and up to nine PVC cylinders (5-cm diameter, 30-cm length) were subsampled in total. Three of these sediment cores were immediately processed for later nucleic acid extraction, while the rest of the sediment cores were transferred into an aquarium for sediment microprofiling (see below). Each sediment core used to extract RNA was quickly moved onto a sterile bench. The sediment was gently extruded, and the top 0–2-cm slice was directly transferred into a sterile 50-mL centrifuge tube, which was snap frozen in liquid N2. Sediment slice samples (n = 12) were transferred from the seafloor to the liquid N2 container within 15–20 min.

Sediment microprofiling

The bottom water in the aquarium was kept at in situ oxygen and temperature (ranging between 3.8 and 7.4 °C depending on station), by circulating water with a cooling unit (Julabo, DE), and by flushing it with a mixture of air and N2/CO2. Sediment microprofiles for dissolved oxygen (O2), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), and nitrous oxide (N2O) concentrations were measured following the protocol illustrated by Marzocchi et al.30. Clark-type gas microsensors for O2, H2S, and N2O were specifically built at Aarhus University (Denmark)58,59,60. At each station, three to five microprofiles were measured in each replicate core (n = 2–3 for stations A, D, and F, and n = 1 for station E) by mounting the microsensors onto a motorized micromanipulator (MM33, Unisense, Denmark), and recording vertical profiles with a four-channel multimeter (Unisense, Denmark) communicating with a laptop. Profiles for O2 and N2O were measured at a vertical resolution of 50–100 µm, while H2S profiles were made using a vertical resolution of 250 μm. A water column of ~5 cm above the sediment was circulated by a gentle flow of air (station A) or N2 (stations D–F) toward the water surface with a 45° angle. This allowed to maintain a constant diffusive boundary layer during measurements. Before each core was measured, the O2 sensor was calibrated using a two-point calibration procedure in O2-saturated bottom water (100% O2) and ca. 1 cm inside the sediment (0% O2). The H2S sensor was calibrated in fresh anoxic solutions containing increasing amounts of a 10 mM Na2S stock solution. The N2O sensor was calibrated in N2O-free water and in N2O-amended water prepared by adding defined volumes of N2O-saturated water to defined volumes of N2O-free water.

Nucleic acid extraction and sequencing

RNA was extracted from ~2 g of thawed sediment following the RNeasy PowerSoil kit (QIAGEN). Sediment was thawed and homogenized but still cold when added into the bead and lysis solution. Extracted RNA was DNase treated with the TURBO DNA-free kit (Invitrogen), and was followed by ribosomal RNA depletion using the bacterial version of the RiboMinus Transcriptome Isolation Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). Quantity and quality of extracted nucleic acids were measured on a NanoDrop One spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). The RNA samples were confirmed to be free of DNA contamination using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent). Library preparation of RNA for sequencing was prepared with the TruSeq RNA Library Prep v2 kit skipping the poly-A selection step (Illumina). The RNA was sequenced on one Illumina NovaSeq6000 S4 lane with a paired-end 2 × 150-bp setup at the Science for Life Laboratory, Stockholm.

Microscopy visual identification

The remaining thawed sediments from station E (n = 3) were diluted in an isotonic solution of NaCl in distilled water, and manually sorted under the Nikon SMZ1000 microscope with ×8 to ×80 magnification. All detected nematodes were fixed in isotonic 4% formaldehyde solution for a minimum of 2 days, processed to absolute glycerin following standard protocols61, and mounted on permanent slides. Light microscopy photographs were taken using a Sony A7 mirrorless camera mounted on a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope with differential interference contrast.

Sequencing output and quality trimming

RNA sequencing yielded on average 81.7 million read pairs per sediment sample (n = 12 with n = 3 per site). Illumina adapters were removed from the raw.fastq sequences by using SeqPrep 1.262, PhiX sequences were removed by mapping the reads against the PhiX genome (NCBI Reference Sequence: NC_001422.1) using bowtie2 2.3.4.363. Quality trimming of the reads was conducted with Trimmomatic 0.3664 with the following parameters: LEADING:20 TRAILING:20 MINLEN:50. Final quality of the trimmed reads was checked with FastQC 0.11.565 in combination with MultiQC 1.766. After quality trimming, an average of 81.2 (min 73.0, max 87.9) million read pairs remained, with an average length of 144 bp. A full list with e.g. sequence facility labels, number of sequences before and after quality trimming, and number of extracted rRNA sequences is available in Supplementary Data 5.

Taxonomic annotation

Taxonomic annotation of the quality-trimmed reads was performed by first extracting SSU rRNA sequences using SortMeRNA 2.1b with the supplied SILVA reference database67, followed by annotation using Kraken2 2.0.768. Kraken2 was run using default settings with a paired-end setup against the small-subunit SILVA v132 NR9969 and NCBI NT databases (databases downloaded: 1 and 12 March 2019, respectively). Both SILVA and NCBI NT were used due to database limitations for nematodes using SILVA (see, e.g., Holovachov et al.70,71). The Kraken2 output reports were combined into a biom-format file using the python package kraken-biom 1.0.1 (with the following setup:—fmt hdf5 -max D–min S). The biom-format file was then converted to a text table using the python package biom-format 2.1.772 and used for further downstream analyses. To remove uncertainty in the dataset taxonomic classifications, less than ten sequence counts were removed. The final 18S rRNA data yielded on average 5,369,739 sequences (SILVA classifications) and 4,177,670 sequences (NCBI NT classifications). The final taxonomy results were normalized between stations as relative abundance (%), and analyzed further in the software Explicet 2.10.573. When visualizing lower taxonomic levels (Fig. 4b–c), freshwater and terrestrial taxa that were likely derived from database errors (Artropoda: Teloganopsis, Stenchaetothrips, and Metatrichoniscoides, and Nematoda: Fictor and Strongyloides) were included in the group “unclassified”. A full list of all classifications is available in Supplementary Data 3.

Protein classification of RNA transcripts

Here we followed a bioinformatics protocol closely resembling the SAMSA2 pipeline74 that uses the DIAMOND + MEGAN approach to classify non-rRNA-merged paired-end reads against a protein database75. Paired-end RNA sequences were merged using PEAR 0.9.1076 (~75% merging rate), and SortMeRNA was used to extract non-rRNA-merged reads. This was followed by protein annotation against NCBI NR (database downloaded 2 April 2019) using the aligner software Diamond 0.9.1077 in conjunction with BLASTX with an e-value threshold of 0.001. The diamond output files were analyzed in MEGAN 6.15.278 for taxonomy using default LCA parameters (NCBI taxonomy database: prot_acc2tax-Nov2018X1.abin) and protein annotation (NCBI NR accession linked to the InterPro database: acc2interpro-June2018X.abin) with databases available with MEGAN. The results of animals, indicated to be alive and active from the 18S rRNA sequence data, were then extracted from MEGAN and analyzed further. Sequence counts were normalized among samples as counts per million sequences (CPM, relative proportion ×1,000,000).

Statistics

Shannon’s H alpha diversity index for the taxonomy data was calculated in Explicet after subsampling read counts to the lowest sample size (Eukaryota SILVA: 4,312,510 counts, Eukaryota NCBI NT: 3,486,047 counts, and Nematodes NCBI NT: 12,776 counts). NMDS multivariate analysis and PERMANOVA tests (9999 permutations) were conducted in the software Past 3.2279. Statistics of taxonomic data was conducted using SPSS 25, and Shapiro–Wilk tests were used to test for normal distribution. Differences between alpha diversity and phylogenetic groups were then tested using one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey tests. All statistical tests are available in Supplementary Data 6.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support these findings are available in the paper and supplementary files. The raw sequence data have been deposited online and can be accessed at the NCBI BioProject PRJNA531756.

References

Michael Beman, J., Arrigo, K. R. & Matson, P. A. Agricultural runoff fuels large phytoplankton blooms in vulnerable areas of the ocean. Nature 434, 211–214 (2005).

Doney, S. C. The growing human footprint on coastal and open-ocean biogeochemistry. Science 328, 1512–1516 (2010).

Carstensen, J., Andersen, J. H., Gustafsson, B. G. & Conley, D. J. Deoxygenation of the Baltic Sea during the last century. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 5628–5633 (2014).

Keeling, R. F., Körtzinger, A. & Gruber, N. Ocean deoxygenation in a warming world. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2, 199–229 (2010).

Schmidtko, S., Stramma, L. & Visbeck, M. Decline in global oceanic oxygen content during the past five decades. Nature 542, 335 (2017).

Levin, L. A. Oxygen minimum zone benthos: adaptation and community response to hypoxia. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. 41, 1–45 (2003).

Diaz, R. J. & Rosenberg, R. Spreading dead zones and consequences for marine ecosystems. Science 321, 926–929 (2008).

Gyllstrom, M. & Hansson, L. A. Dormancy in freshwater zooplankton: Induction, termination and the importance of benthic-pelagic coupling. Aquat. Sci. 66, 274–295 (2004).

Roman M. R., Brandt S. B., Houde E. D., Pierson J. J. Interactive effects of hypoxia and temperature on coastal pelagic zooplankton and fish. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 1–18 (2019).

Broman E., Brüsin M., Dopson M., Hylander S. Oxygenation of anoxic sediments triggers hatching of zooplankton eggs. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 282, 1–7 (2015).

Cook, A. A. et al. Nematode abundance at the oxygen minimum zone in the Arabian Sea. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 47, 75–85 (2000).

Giere O. Meiobenthology: The Microscopic Motile Fauna of Aquatic Sediments, 2nd edn. (Springer-Verlag, 2009).

Zeppilli, D. et al. Characteristics of meiofauna in extreme marine ecosystems: a review. Mar. Biodivers. 48, 35–71 (2018).

Zeppilli, D. et al. Is the meiofauna a good indicator for climate change and anthropogenic impacts? Mar. Biodivers. 45, 505–535 (2015).

Moens T., et al. Ecology of free-living marine nematodes. Handbook of Zoology (ed. Schmidt-Rhaesa, A.) (De Gruyter, Berlin, 2013).

Fenchel T. Anaerobic eukaryotes. in: Anoxia: Evidence for Eukaryote Survival and Paleontological Strategies (eds Altenbach, A.V. Bernhard, J.M. Seckbach, J.) (Springer Netherlands, 2012).

Sperling, E. A. et al. Oxygen, ecology, and the Cambrian radiation of animals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13446–13451 (2013).

Canfield, D. E. et al. A cryptic sulfur cycle in oxygen-minimum–zone waters off the Chilean coast. Science 330, 1375 (2010).

Wright, J. J., Konwar, K. M. & Hallam, S. J. Microbial ecology of expanding oxygen minimum zones. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 381–394 (2012).

Diaz, R. J. & Rosenberg, R. Marine benthic hypoxia: a review of its ecological effects and the behavioural responses of benthic macrofauna. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 33, 245–203 (1995).

Vaquer-Sunyer, R. & Duarte, C. M. Sulfide exposure accelerates hypoxia‐driven mortalit. Limnol. Oceanogr. 55, 1075–1082 (2010).

Fenchel, T. & Finlay, B. J. Ecology and Evolution in Anoxic Worlds. (Oxford University Press, Oxford; New York, 1995).

Thiermann, F., Vismann, B. & Giere, O. Sulphide tolerance of the marine nematode Oncholaimus campylocercoides—a result of internal sulphur formation? Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 193, 251–259 (2000).

Polz, M. F., Felbeck, H., Novak, R., Nebelsick, M. & Ott, J. A. Chemoautotrophic, sulfur-oxidizing symbiotic bacteria on marine nematodes: Morphological and biochemical characterization. Micro. Ecol. 24, 313–329 (1992).

Han Y., Perner M. The globally widespread genus Sulfurimonas: versatile energy metabolisms and adaptations to redox clines. Front. Microbiol. 6, 1–17 (2015).

Burdige D. J. Geochemistry of Marine Sediments. (PRINCETON University Press, 2006).

Bonaglia, S. et al. Denitrification and DNRA at the Baltic Sea oxic–anoxic interface: substrate spectrum and kinetics. Limnol. Oceanogr. 61, 1900–1915 (2016).

Kwast, K. E., Burke, P. V., Staahl, B. T. & Poyton, R. O. Oxygen sensing in yeast: evidence for the involvement of the respiratory chain in regulating the transcription of a subset of hypoxic genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 5446–5451 (1999).

Cristescu M. E. Can environmental RNA revolutionize biodiversity science? Trends Ecol. Evol. 694–697 (2019).

Marzocchi, U. et al. Transient bottom water oxygenation creates a niche for cable bacteria in long-term anoxic sediments of the Eastern Gotland Basin. Environ. Microbiol. 20, 3031–3041 (2018).

Altenbach A., Bernhard J. M., Seckbach J. Anoxia: Evidence for Eukaryote Survival and Paleontological Strategies. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2011).

Wetzel, M. A., Fleeger, J. W. & Powers, S. P. Effects of hypoxia and anoxia on meiofauna: a review with new data from the Gulf of Mexico. Coast. Hypoxia 58, 165 (2001).

Rabalais, N. N., Turner, R. E. & Wiseman, W. J. Jr Gulf of Mexico hypoxia, aka “The dead zone”. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 33, 235–263 (2002).

Sergeeva, N. G., Mazlumyan, S. A., Lichtschlag, A. & Holtappels, M. Benthic Protozoa and Metazoa living in deep anoxic and hydrogen sulfide conditions of the Black Sea: Direct observations of actively moving Ciliophora and Nematoda. International Journal of Marine Science 4, 1–11 (2014).

Sergeeva, N. G., Gooday, A. J., Mazlumyan, S. A., Kolesnikova, E. A., Lichtschlag, A., Kosheleva, T. N., & Anikeeva, O. V. Anoxia (Editors: Alexander V. Altenbach, Joan M. Bernhard, Joseph Seckbach) Meiobenthos of the oxic/anoxic interface in the Southwestern region of the Black Sea: abundance and taxonomic composition (Springer, Dordrecht, 2012).

Hentschel, U., Berger, E. C., Bright, M., Felbeck, H. & Ott, J. A. Metabolism of nitrogen and sulfur in ectosymbiotic bacteria of marine nematodes (Nematoda, Stilbonematinae). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 183, 149–158 (1999).

Taheri, M., Braeckman, U., Vincx, M. & Vanaverbeke, J. Effect of short-term hypoxia on marine nematode community structure and vertical distribution pattern in three different sediment types of the North Sea. Mar. Environ. Res. 99, 149–159 (2014).

Steyaert, M. et al. Responses of intertidal nematodes to short-term anoxic events. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 345, 175–184 (2007).

Taheri, M., Grego, M., Riedel, B., Vincx, M. & Vanaverbeke, J. Patterns in nematode community during and after experimentally induced anoxia in the northern Adriatic Sea. Mar. Environ. Res. 110, 110–123 (2015).

Tahseen, Q. Nematodes in aquatic environments: adaptations and survival strategies. Biodivers. J. 3, 13–40 (2012).

Shih, J., Platzer, E., Thompson, S. & Carroll, E. Jr. Characterization of key glycolytic and oxidative enzymes in Steinernema carpocapsae. J. Nematol. 28, 431 (1996).

Pilz, M., Hohberg, K., Pfanz, H., Wittmann, C. & Xylander, W. E. R. Respiratory adaptations to a combination of oxygen deprivation and extreme carbon dioxide concentration in nematodes. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 239, 34–40 (2017).

Tchesunov, A. V., Portnova, D. A. & van Campenhout, J. Description of two free-living nematode species of Halomonhystera disjuncta complex (Nematoda: Monhysterida) from two peculiar habitats in the sea. Helgol. Mar. Res. 69, 57–85 (2015).

Ott, J. et al. Tackling the sulfide gradient: a novel strategy involving marine nematodes and chemoautotrophic ectosymbionts. Mar. Ecol. 12, 261–279 (1991).

Chandel, N. S., Budinger, G. R., Choe, S. H. & Schumacker, P. T. Cellular respiration during hypoxia. Role of cytochrome oxidase as the oxygen sensor in hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 18808–18816 (1997).

Castello, P. R., David, P. S., McClure, T., Crook, Z. & Poyton, R. O. Mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase produces nitric oxide under hypoxic conditions: Implications for oxygen sensing and hypoxic signaling in eukaryotes. Cell Metab. 3, 277–287 (2006).

Radzikowski, J. Resistance of dormant stages of planktonic invertebrates to adverse environmental conditions. J. Plankton Res. 35, 707–723 (2013).

Denekamp, N. Y. et al. Discovering genes associated with dormancy in the monogonont rotifer Brachionus plicatilis. BMC Genom. 10, 108–108 (2009).

Kizito, Y. S. & Nauwerck, A. Temporal and vertical distribution of planktonic rotifers in a meromictic crater lake, Lake Nyahirya (Western Uganda). Hydrobiologia 313, 303–312 (1995).

Esparcia A., Miracle M. R., Serra M. Brachionus plicatilis tolerance to low oxygen concentrations. in: Rotifer Symposium V (eds Ricci C, Snell TW, King CE). (Springer Netherlands, 1989).

Ozaki, Y., Kaneko, G., Yanagawa, Y. & Watabe, S. Calorie restriction in the rotifer Brachionus plicatilis enhances hypoxia tolerance in association with the increased mRNA levels of glycolytic enzymes. Hydrobiologia 649, 267–277 (2010).

Snell, T. W., Johnston, R. K. & Jones, B. L. Hypoxia extends lifespan of Brachionus manjavacas (Rotifera). Limnetica 38, 159–166 (2019).

Wiegand, G. & Remington, S. J. Citrate synthase: structure, control, and mechanism. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 15, 97–117 (1986).

Wetzel, M., Weber, A. & Giere, O. Re-colonization of anoxic/sulfidic sediments by marine nematodes after experimental removal of macroalgal cover. Mar. Biol. 141, 679–689 (2002).

Dalsgaard, T., De Brabandere, L. & Hall, P. O. J. Denitrification in the water column of the central Baltic Sea. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 106, 247–260 (2013).

Neumann, T., Radtke, H. & Seifert, T. On the importance of Major Baltic Inflows for oxygenation of the central Baltic Sea. J. Geophys. Res. 122, 1090–1101 (2017).

Blomqvist, S., Ekeroth, N., Elmgren, R. & Hall, P. O. J. Long overdue improvement of box corer sampling. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 538, 13–21 (2015).

Revsbech, N. P. An oxygen microsensor with a guard cathode. Limnol. Oceanogr. 34, 474–478 (1989).

Jeroschewski, P., Steuckart, C. & Kühl, M. An amperometric microsensor for the determination of H2S in aquatic environments. Anal. Chem. 68, 4351–4357 (1996).

Andersen, K., Kjær, T. & Revsbech, N. P. An oxygen insensitive microsensor for nitrous oxide. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 81, 42–48 (2001).

De Grisse A. T. Redescription ou Modifications De Quelques Techniques Utilisées Dans L’étude Des Nématodes Phytoparasitaires. (Mededelingen van de Rijksfakulteit voor Landbouwwetenschappen, Gent, 1969).

St John J. SeqPrep. (2011). Available: https://github.com/jstjohn/SeqPrep.

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357 (2012).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Andrews S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. (2010).

Ewels, P., Magnusson, M., Käller, M. & Lundin, S. MultiQC: summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 32, 3047–3048 (2016).

Kopylova, E., Noé, L. & Touzet, H. SortMeRNA: fast and accurate filtering of ribosomal RNAs in metatranscriptomic data. Bioinformatics 28, 3211–3217 (2012).

Wood D. E., Salzberg S. L. J. G. B. Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol. 15, R46 (2014).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596 (2013).

Holovachov O., Haenel Q., Bourlat S. J., Jondelius U. Taxonomy assignment approach determines the efficiency of identification of OTUs in marine nematodes. R. Soc. Open Sci. 4, 1–15 (2017).

Broman, E. et al. Salinity drives meiofaunal community structure dynamics across the Baltic ecosystem. Mol. Ecol. 28, 3813–3829 (2019).

McDonald, D. et al. The Biological Observation Matrix (BIOM) format or: how I learned to stop worrying and love the ome-ome. GigaScience 1, 7 (2012).

Robertson, C. E. et al. Explicet: graphical user interface software for metadata-driven management, analysis and visualization of microbiome data. Bioinformatics 29, 3100–3101 (2013).

Westreich, S. T., Treiber, M. L., Mills, D. A., Korf, I. & Lemay, D. G. SAMSA2: a standalone metatranscriptome analysis pipeline. BMC Bioinform. 19, 175–175 (2018).

Bağcı C., Beier S., Górska A., Huson D. H. Introduction to the Analysis of Environmental Sequences: Metagenomics with MEGAN. in: Evolutionary Genomics: Statistical and Computational Methods (ed Anisimova M). (Springer, New York, 2019).

Zhang, J., Kobert, K., Flouri, T. & Stamatakis, A. PEAR: a fast and accurate Illumina Paired-End reAd mergeR. Bioinformatics 30, 614–620 (2014).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59–60 (2015).

Huson, D. H. & Mitra, S. Introduction to the analysis of environmental sequences: metagenomics with MEGAN. Methods Mol. Biol. 856, 415–429 (2012).

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T. & Ryan, P. D. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 4, 9 (2001).

Acknowledgements

Individual financial support was provided by the Swedish Research Council Formas to SB (Grant no. 2017-01513); the Stockholm University’s strategic funds for Baltic Sea research to F.N.; the Swedish Research Council Formas to F.N. (Grant no. 2016-00804); the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency’s Research Grant (NV-802-0151-18) to FN in collaboration with the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management; the Swedish Research Council VR to P.O.J.H. (Grant no. 2015-03717); the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship grant to UM (Grant no. 656385). The authors acknowledge support from the National Genomics Infrastructure in Stockholm funded by Science for Life Laboratory, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation and the Swedish Research Council, and SNIC/Uppsala Multidisciplinary Center for Advanced Computational Science for assistance with massively parallel sequencing and access to the UPPMAX computational infrastructure. We thank Simon Creer for giving feedback on the paper, the captain and crew of R/V Skagerak (University of Gothenburg) for support at sea, Lars B. Pedersen at Aarhus University for sensor constructions, and Volker Brüchert for making the gas chromatographer available at the Department of Geological Sciences, Stockholm University. Open access funding provided by Stockholm University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.B. and S.B. drafted the paper together. E.B. conducted molecular laboratory work, bioinformatics, and molecular data analyses. S.B. sampled in the field, conducted sediment microprofiling, analyzed N2O samples, and conducted chemistry data analyses. O.H. sorted and identified nematodes and gave feedback on the paper. U.M. helped with chemistry data analysis and gave feedback on the paper. P.H. led the sea expedition and gave feedback on the paper. F.J.A.N. coordinated the study and helped draft the paper. The research was designed by S.B., E.B., and F.J.A.N.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Broman, E., Bonaglia, S., Holovachov, O. et al. Uncovering diversity and metabolic spectrum of animals in dead zone sediments. Commun Biol 3, 106 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-0822-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-0822-7

This article is cited by

-

Long-Term Pollution Does Not Inhibit Denitrification and DNRA by Adapted Benthic Microbial Communities

Microbial Ecology (2023)

-

Reconstruction of 100-year dynamics in Daphnia spawning activity revealed by sedimentary DNA

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

The effect of estuarine system on the meiofauna and nematodes in the East Siberian Sea

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.