Abstract

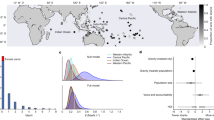

Marine ecosystem declines have spurred global efforts to restore degraded habitats, manage marine life and enhance recreation opportunities by installing built structures called artificial reefs in seascapes. Evidence suggests that artificial reefs generate ecosystem services and risks, yet a fundamental ecological characteristic—the area of seafloor occupied by these constructed reefs—remains poorly quantified. Here we calculate the physical footprint (seafloor extent) of artificial reefs in the US ocean using spatial data from all 17 US coastal states with ocean reefing programmes. Our synthesis revealed that purposely sunk reef structures such as ships and concrete pipes occupy 19.23 km2 of the ocean through 2020. Over the past five decades (1970–2020), the intentional reef footprint increased 20.85-fold (~1,980%), but this rate of increase slowed in the past decade (2010–2020) to 1.12-fold (~12%). These baseline findings will inform sustainable use of built marine infrastructure and generation of ecological functions.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The US artificial reef inventory produced by the authors is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10235600. The archive includes compiled data on permitted reef zones (Data S1) and reefed structures (Data S2).

References

Gissi, E. et al. A review of the combined effects of climate change and other local human stressors on the marine environment. Sci. Total Environ. 755, 142564 (2021).

Halpern, B. S., Selkoe, K. A., Micheli, F. & Kappel, C. V. Evaluating and ranking the vulnerability of global marine ecosystems to anthropogenic threats. Conserv. Biol. 21, 1301–1315 (2007).

Eddy, T. D. et al. Global decline in capacity of coral reefs to provide ecosystem services. One Earth 4, 1278–1285 (2021).

Scyphers, S. B., Powers, S. P., Heck, K. L. Jr & Byron, D. Oyster reefs as natural breakwaters mitigate shoreline loss and facilitate fisheries. PLoS ONE 6, e22396 (2011).

Krumhansl, K. A. et al. Global patterns of kelp forest change over the past half-century. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 13785–13790 (2016).

Waycott, M. et al. Accelerating loss of seagrasses across the globe threatens coastal ecosystems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 12377–12381 (2009).

Duarte, C. M. et al. Rebuilding marine life. Nature 580, 39–51 (2020).

Saunders, M. I. et al. Bright spots in coastal marine ecosystem restoration. Curr. Biol. 30, R1500–R1510 (2020).

Zhang, Y. S. et al. A global synthesis reveals gaps in coastal habitat restoration research. Sustainability 10, 3–5 (2018).

Becker, A., Taylor, M. D., Folpp, H. & Lowry, M. B. Managing the development of artificial reef systems: the need for quantitative goals. Fish. Fish. 19, 740–752 (2018).

Vivier, B. et al. Marine artificial reefs, a meta-analysis of their design, objectives and effectiveness. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01538 (2021).

Santos, M. N. & Monteiro, C. C. A fourteen-year overview of the fish assemblages and yield of the two oldest Algarve artificial reefs (southern Portugal). Hydrobiologia 580, 225–231 (2007).

Paxton, A. B. et al. Meta-analysis reveals artificial reefs can be effective tools for fish community enhancement but are not one-size-fits-all. Front. Mar. Science https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.00282 (2020).

Lima, J. S., Zalmon, I. R. & Love, M. Overview and trends of ecological and socioeconomic research on artificial reefs. Mar. Environ. Res. 145, 81–96 (2019).

Cresson, P., Ruitton, S. & Harmelin-Vivien, M. Artificial reefs do increase secondary biomass production: mechanisms evidenced by stable isotopes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 509, 15–26 (2014).

Layman, C. A., Allgeier, J. E. & Montaña, C. G. Mechanistic evidence of enhanced production on artificial reefs: a case study in a Bahamian seagrass ecosystem. Ecol. Eng. 95, 574–579 (2016).

Esquivel, K. E., Hesselbarth, M. H. K. & Allgeier, J. E. Mechanistic support for increased primary production around artificial reefs. Ecol. Appl. 32, e2617 (2022).

Bishop, M. J. et al. Effects of ocean sprawl on ecological connectivity: impacts and solutions. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 492, 7–30 (2017).

Airoldi, L., Turon, X., Perkol-Finkel, S., Rius, M. & Keller, R. Corridors for aliens but not for natives: effects of marine urban sprawl at a regional scale. Divers. Distrib. 21, 755–768 (2015).

Dafforn, K. A., Glasby, T. M. & Johnston, E. L. Comparing the invasibility of experimental ‘reefs’ with field observations of natural reefs and artificial structures. PLoS ONE 7, e38124 (2012).

Bohnsack, J. A. Are high densities of fishes at artificial reefs the result of habitat limitation or behavioral preference? Bull. Mar. Sci. 44, 631–645 (1989).

Collins, K. Environmental impact assessment of a scrap tyre artificial reef. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 59, S243–S249 (2002).

Chen, Q. & Chen, P. Changes in the heavy metals and petroleum hydrocarbon contents in seawater and surface sediment in the year following artificial reef construction in the Pearl River Estuary, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 27, 6009–6021 (2020).

Sherman, R. L. & Spieler, R. E. in Environmental Problems in Coastal Regions VI (ed C.A. Brebbia) 215–223 (Wessex Institute of Technology, 2006).

Islam, G. M. N., Noh, K. M., Sidique, S. F., Noh, A. F. M. & Ali, A. Economic impacts of artificial reefs on small-scale fishers in peninsular Malaysia. Hum. Ecol. 42, 989–998 (2014).

Brochier, T. et al. Successful artificial reefs depend on getting the context right due to complex socio–bio–economic interactions. Sci. Rep. 11, 16698 (2021).

Bugnot, A. B. et al. Current and projected global extent of marine built structures. Nat. Sustain. 4, 33–41 (2021).

Ramm, L. A. W., Florisson, J. H., Watts, S. L., Becker, A. & Tweedley, J. R. Artificial reefs in the Anthropocene: a review of geographical and historical trends in their design, purpose, and monitoring. Bull. Mar. Sci. 97, 699–728 (2021).

Steward, D. a. N. et al. Quantifying spatial extents of artificial versus natural reefs in the seascape. Front. Mar. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.980384 (2022).

Bayraktarov, E. et al. Priorities and motivations of marine coastal restoration research. Front. Mar. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.00484 (2020).

Schlappy, M. L. & Hobbs, R. J. A triage framework for managing novel, hybrid, and designed marine ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 3215–3223 (2019).

Sutton-Grier, A. E., Wowk, K. & Bamford, H. Future of our coasts: the potential for natural and hybrid infrastructure to enhance the resilience of our coastal communities, economies and ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Policy 51, 137–148 (2015).

Salaün, J., Pioch, S. & Dauvin, J.-C. Socio-ecological analysis to assess the success of artificial reef projects. J. Coast. Res. https://doi.org/10.2112/jcoastres-d-21-00072.1 (2022).

Hixon, M. A. & Beets, J. P. Shelter characteristics and Caribbean fish assemblages: experiments with artificial reefs. Bull. Mar. Sci. 44, 666–680 (1989).

Ido, S. & Shimrit, P.-F. Blue is the new green—ecological enhancement of concrete based coastal and marine infrastructure. Ecol. Eng. 84, 260–272 (2015).

Rella, A., Perkol-Finkel, S., Neuman, A. & Ido, S. in Coasts, Marine Structures and Breakwaters (ed Burgess, K.) 823–832 (ICE Publishing, 2017).

Macreadie, P. I., Fowler, A. M. & Booth, D. J. Rigs-to-reefs: Will the deep sea benefit from artificial habitat? Front. Ecol. Environ. 9, 455–461 (2011).

Lemoine, H. R., Paxton, A. B., Anisfeld, S. C., Rosemond, R. C. & Peterson, C. H. Selecting the optimal artificial reefs to achieve fish habitat enhancement goals. Biol. Conserv. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108200 (2019).

Rosemond, R. C., Paxton, A. B., Lemoine, H. R., Fegley, S. R. & Peterson, C. H. Fish use of reef structures and adjacent sand flats: implications for selecting minimum buffer zones between artificial reefs and existing reefs. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 587, 187–199 (2018).

Lindberg, W. J. et al. Density-dependent habitat selection and performance by a large mobile reef-fish. Ecol. Appl. 16, 731–746 (2006).

Paxton, A. B., Steward, D. a. N., Harrison, Z. H. & Taylor, J. C. Fitting ecological principles of artificial reefs into the ocean planning puzzle. Ecosphere https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3924 (2022).

Heery, E. C. et al. Identifying the consequences of ocean sprawl for sedimentary habitats. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 492, 31–48 (2017).

Paxton, A. B. et al. Artificial reefs facilitate tropical fish at their range edge. Commun. Biol. 2, 168 (2019).

Moore, J. D. Long-term corrosion processes of iron and steel shipwrecks in the marine environment: a review of current knowledge. J. Marit. Archaeol. 10, 191–204 (2015).

Raineault, N. A., Trembanis, A. C., Miller, D. C. & Capone, V. Interannual changes in seafloor surficial geology at an artificial reef site on the inner continental shelf. Cont. Shelf Res. 58, 67–78 (2013).

Baynes, T. W. & Szmant, A. M. Effect of current on the sessile benthic community structure of an artificial reef. Bull. Mar. Sci. 44, 545–566 (1989).

Turpin, R. & Bortone, S. A. Pre- and post-hurricane assessment of artificial reefs: evidence for potential use as refugia in a fishery management strategy. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 59, S74–S82 (2002).

Champion, C., Suthers, I. M. & Smith, J. A. Zooplanktivory is a key process for fish production on a coastal artificial reef. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 541, 1–14 (2015).

Dahl, K. A. & Patterson, W. F. Habitat-specific density and diet of rapidly expanding invasive red lionfish, Pterois volitans, populations in the northern Gulf of Mexico. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0105852 (2014).

Claisse, J. T. et al. Oil platforms off California are among the most productive marine fish habitats globally. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 15462–15467 (2014).

zu Ermgassen, P. S. E. et al. Estimating and applying fish and invertebrate density and production enhancement from seagrass, salt marsh edge, and oyster reef nursery habitats in the Gulf of Mexico. Estuaries Coast. 44, 1588–1603 (2021).

Topping, D. T. & Szedlmayer, S. T. Home range and movement patterns of red snapper (Lutjanus campechanus) on artificial reefs. Fish. Res. 112, 77–84 (2011).

Topping, D. T. & Szedlmayer, S. T. Site fidelity, residence time and movements of red snapper Lutjanus campechanus estimated with long-term acoustic monitoring. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 437, 183–200 (2011).

Collins, A. B., Barbieri, L. R., McBride, R. S., McCoy, E. D. & Motta, P. J. Reef relief and volume are predictors of Atlantic goliath grouper presence and abundance in the eastern Gulf of Mexico. Bull. Mar. Sci. 91, 399–418 (2015).

Keenan, S. F., Switzer, T. S., Knapp, A., Weather, E. J. & Davis, J. Spatial dynamics of the quantity and diversity of natural and artificial hard bottom habitats in the eastern Gulf of Mexico. Cont. Shelf Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2021.104633 (2022).

Pickens, B. A., Taylor, J. C., Finkbeiner, M., Hansen, D. & Turner, L. Modeling sand shoals on the US Atlantic shelf: moving beyond a site-by-site approach. J. Coast. Res. https://doi.org/10.2112/jcoastres-d-20-00084.1 (2021).

Gittman, R. K. et al. Engineering away our natural defenses: an analysis of shoreline hardening in the US. Front. Ecol. Environ. 13, 301–307 (2015).

Blouet, S., Bramanti, L. & Guizien, K. Artificial reefs geographical location matters more than shape, age and depth for sessile invertebrate colonization in the Gulf of Lion (northwestern Mediterranean Sea). Peer Community J. 2, e24 (2022).

R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing Version 4.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020); https://www.R-project.org/

ArcGIS Pro Version 2.9 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, 2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Schobernd, M. Bollinger, J. Walter and T. Barnes for thoughtful reviews of the manuscript. A.B.P. was supported during part of the study by CSS under NOAA/NCCOS Contract #EA133C17BA0062. D.N.S. was supported during part of the study by the Duke Rachel Carson Scholar Program. We thank R. Martore (South Carolina), J. Tinsman (Delaware), S. Newlin (Delaware), M. McDonough (Louisiana), M.l. Malpezzi (Maryland), M. Hawkins (Maryland), E. Wilkins (California) and B. Owens (California) for contributing artificial reef data from their respective states. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the US Government, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B.P., D.N.S., G.T.K., J.C.T., N.M.B. and K.L.R. conceptualized this research. Data on artificial reefs were provided by artificial reef coordinators for each state: K.J.M., J.R., Z.H.H., J.S.B., C.B., A.N., E.S., P.J.C., C.L., P.D.B., M.R., D.C.N., R.B.R., D.T.W., J.B.S. and P.W. Some state artificial reef coordinators converted their states’ data into the standard project format, and in other cases D.N.S. and A.B.P. converted data into the project format. A.B.P. and D.N.S. developed the footprint calculation approach with support from G.T.K., J.C.T., N.M.B. and K.L.R. A.B.P., D.N.S., K.J.M. and J.R. led development of structure categorization. M.R., D.T.W., Z.H.H., J.S.B., D.C.N., R.B.R., P.J.C. and C.B. assisted in developing structure categorizations and categorizing their states’ structures. J.R. wrote code required for Florida data wrangling and footprint estimations. R.B.R. and D.C.N. conducted spatial analyses for Alabama reef structures. A.B.P. and D.N.S. cleaned, processed and analysed the overall dataset. A.B.P., D.N.S. and B.J.R. developed synthesis code and produced figures and tables. A.B.P. and D.N.S. drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Sustainability thanks Sylvain Pioch, Timothée Brochier and Chungkuk Jin for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paxton, A.B., Steward, D.N., Mille, K.J. et al. Artificial reef footprint in the United States ocean. Nat Sustain 7, 140–147 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01258-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01258-7

This article is cited by

-

Mapped US artificial reef footprint

Nature Sustainability (2024)