Abstract

Tailoring the electrical transport properties of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides can enable the formation of atomically thin circuits. In this work, cyclic hydrogen and oxygen plasma exposures are utilized to introduce defects and oxidize MoS2 in a controlled manner. This results in the formation of sub-stochiometric MoO3−x, which transforms the semiconducting behavior to metallic conduction. To demonstrate functionality, single flakes of MoS2 were lithographically oxidized using electron beam lithography and subsequent plasma exposures. This enabled the formation of atomically thin inverters from a single flake of MoS2, which represents an advancement toward atomically thin circuitry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) exhibit interesting material properties which arise from confinement.1,2 TMDs are comprised of a MX2 stoichiometry, where M is a transition metal and X is a chalcogen (S, Se, or Te). Single-layer TMDs from group 6 transition metals, such as MoS2, are direct bandgap semiconductors.3 MoS2 has shown promise for incorporation in high-performance microelectronic and optoelectronic devices.4 For example, MoS2 is commonly used to create field-effect transistors, which exhibit on–off ratios of >106 and field-effect mobility of ~300 cm2/Vs.5,6 Besides transistors, group 6 TMDs have been used as an active layer for applications in light emitting diodes7 and catalysts.8,9 Recently, atomically thin circuits have been created by forming lateral metallic/semiconducting heterostructures between graphene and TMDs.10,11

Defects can strongly influence the electronic properties of MoS2.12,13 Atomic vacancies, interstitials, and grain boundaries have been extensively studied in MoS2. Of particular relevance to this work, sulfur vacancies are generally present in single-layer MoS2 upon synthesis,14 and they can be induced by processes such as ion beam exposure,15,16,17,18,19 plasma exposure,20,21,22,23,24,25 and annealing,26 to name a few. The chalcogen vacancies in MoS2 behave like highly localized n-type dopants, which are nearly dispersionless.27 These vacancies can also be isoelectronically filled via oxygen substitution28; however recent work has also shown that oxygen termination of edge states can induce metallic behavior.29 With extensive chalcogen vacancy formation and subsequent oxidation, sub-stoichiometric MoO3−x can exhibit metallic behavior since oxygen vacancies act as donor levels in MoO3.30

In this work, cycles of hydrogen and atmospheric exposure (or oxygen plasma) are used to (1) create chalcogen vacancies in MoS2 and then (2) oxidize the vacancies. MoS2 is lithographically converted to MoO3−x in a highly selective manner. This enables portions of a single MoS2 layer to be oxidized, which forms a lateral junction between semiconducting MoS2 and conducting MoO3−x. The optimized cyclic plasma is applied to lithographically patterned MoS2 to fabricate a functioning resistor-loaded inverter in a single-layer of MoS2; where the plasma exposed region acts as the resistor and the un-exposed region acts as the semiconductor, thus producing lateral semiconducting/metallic junctions that are necessary for the formation of truly atomically thin circuits.

Results and discussion

Previous work has demonstrated that extended H2 plasma exposures can be used to completely strip the top layer of sulfur atoms from MoS2.31 In order to controllably introduce S vacancies into MoS2, we utilized a 400 W inductively coupled remote H2 plasma (additional details in Methods section). Figure 1a shows optical micrographs of MoS2 flakes after exposure to varying times of H2 plasma. The exposures were done in cycles, in which the MoS2 was exposed to the plasma for ~10 s and then removed from the plasma chamber and exposed to atmosphere for imaging and electrical characterization (~10 min). The MoS2 flakes become more optically transparent with increasing total plasma exposure time. An atomic force microscopic (AFM) image, shown in Fig. 1b, after 100 s of total H2 plasma exposure indicates that the flake is still intact and that the change in optical contrast does not correspond to simple plasma etching of the MoS2. In fact, the flake thickness after plasma exposure was ~1 nm, which is notably thicker than an MoS2 monolayer (~0.7 nm). This suggests that the plasma-exposed MoS2 likely oxidized after exposure to atmosphere, as similar increases in thickness have been previously noted.32 Indeed, first-principles calculations and experimental studies have shown that S vacancies will readily oxidize in atmosphere.28 Additionally, oxidation of sulfur vacancies has been demonstrated as a self-limiting half-reaction in atomic-layer-etching applications.33 Owing to the favorable energetics and self-limiting nature, the ~10-min atmospheric exposure was believed to be sufficient to oxidize the sulfur vacancies, and additional atmospheric exposure time would have resulted in minimal additional oxidation.

Electronic properties of plasma treated MoS2. a Optical micrographs of pristine MoS2 and after various H2 plasma exposure time. b Atomic force microscopic image after 100 s of total H2 plasma exposure. Scale bar is 4 μm. c Transfer curves for pristine and cyclic and continuous H2 plasma exposed MoS2. d On/off ratio as function of the number of 10 s plasma+atmosphere cycles. Optical image of field-effect transistor is inset. Scale bar is 5 μm. e Sheet resistance (VGS = −25 V) as function of the number of 10 s plasma+atmosphere cycles. Inset shows linear I–V curve after five plasma cycles. f Average on-current (VGS = 30 V) for MoS2 transistors as a function of plasma cycles. Error bars for all figures show the standard error of the mean

Field-effect transistors (FETs) were fabricated to determine the effect of cyclic H2 plasma exposures followed by exposure to atmosphere on the electrical transport of MoS2. Figure 1c shows transfer curves for MoS2 exposed to varying H2 plasma exposures. Notably, the pristine device exhibits n-type characteristics with a large on/off ratio of ~109. MoS2 was plasma treated in approximately 10-s increments and subsequently exposed to ~10 min of atmosphere after each cycle (yellow) and treated with the equivalent continuous plasma time of 80 s (red). The incremental and continuous plasma exposures have very different effects on the transport properties of MoS2. The continuous plasma exposure induces insulating behavior in the MoS2, whereas the cyclic plasma exposure results in metallic-like conduction, which exhibits very little current variation with gate modulation. This suggests that exposure to atmosphere after the introduction of S vacancies, and not solely S vacancy generation, dictates the metallic conduction in the MoS2. The tunability of the transport was explored by measuring the electrical properties of MoS2, which were exposed to 10 s cycles of H2 plasma+an atmosphere exposure. The characteristics were collected as a function of cycles from six separate devices to determine the average and variance. Transfer curves for all six devices can be found in Figure S1. Figure 1d shows the on/off ratio collected from transfer curves as a function of the total plasma+atmosphere cycles. The on/off ratio rapidly decreases and hence quenches the semiconducting behavior. After five 10-s cycles of plasma treatment and atmosphere exposure, the on/off ratio is reduced to ~1 and saturates for additional cycles. Figure 1e reports the sheet resistance (Rs) of MoS2 in its “off” state (VG ~ -25 V). Rs decreases until it reaches a minimum value after 5–6 cycles of plasma/atmosphere exposures. This value corresponds with metallic-like behavior since the sheet resistance is at a minimum and the on/off ratio is ~1. The inset in Fig. 1e also reveals linear I–V characteristics, which demonstrates Ohmic contact, and behavior consistent with metallic-like transport. As the MoS2 is exposed to additional cycles of plasma/atmosphere, Rs begins to increase. This is likely due to excessive defect introduction that scatters carriers and further oxidation or material loss, which reduces the carrier concentration. The on-current (VGS = 30 V) is reported in Fig. 1f. Notably, there is a sharp decrease in the on-current after a single plasma cycle. With subsequent plasma cycles, the on-current gradually increases and plateaus when the metallic conduction is realized after five cycles. In this context, the term “on-current” is used loosely, as the metallic conduction shows no gate modulation and hence no “on-current.” With excessive plasma exposure (>9 cycles), the on-current sharply drops due to excessive defect introduction in the material. The change in off-current (Fig. 1e) is more pronounced than the change in on-current due to the absence of electrostatic doping.

Raman measurements were performed to characterize the extent of defects created by H2 plasma exposure. The Raman spectra for MoS2 is reported in Fig. 2a. Notably, the E12g, A1g, and LA(M) peaks are highlighted. To analyze the effect of plasma/atmosphere cycles, the peaks were fitted using a Gaussian/Lorentz (Voight) model. An example of this fit is shown in Fig. 2b. As expected, the full width at half maximum for the E12g and A1g peaks increase with the number of plasma cycles (Fig. 2c). This peak broadening indicates that the defect concentration scales with total plasma exposure time. Furthermore, the E12g and A1g peaks exhibit a shift in peak position as well as reduction in peak intensity (see Figure S2). However, with increasing plasma time, there is a demonstrable increase in the intensity of the LA(M) peak at ~227 cm−1. This is attributed to defect-induced scattering, which arises from zone-edge phonon modes.34 The ratio of the LA(M) peak intensity to that of the E12g and A1g peaks can be used to determine the average inter-defect distance (LD) by the following relationship34:

where I is the Raman peak intensity. A plot of the relationship between LD and the cumulative plasma exposure time is shown in Fig. 2d. An inter-defect spacing of around 2.1/nm is achieved after 5 plasma cycles, which corresponds with the onset of metallic behavior. Beyond six cycles, the A1g peak is no longer discernable.

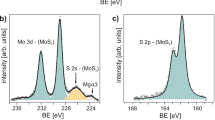

Ex situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was conducted to determine the chemical effects of the cyclic and continuous plasma treatments on MoS2. Figure 3a shows the XPS spectra of the Mo 3d region, whereas Fig. 3b shows the S 2p region. For the pristine sample, the peaks at around 229 eV and 232 eV correspond to Mo4+, which is expected for MoS2. A sample was exposed to 75 s of H2 plasma to emulate the cumulative hydrogen H2 plasma necessary to fully metalize the cyclic sample. Mo5+ (44%), Mo6+ (13%), and metallic Mo (43%) are exhibited, and the S 2p peak is no longer discernable. Consistent with previous work,31 this indicates that the H2 plasma effectively etches the sulfur atoms; however, much of the Mo atoms remain. The small Mo6+ presence suggests modest oxidation, which likely occurred during the atmospheric exposure between the H2 plasma treatment and the XPS measurements (~3 days in low vacuum). Although the MoS2 exposed with a continuous H2 plasma contains a high percentage of metallic Mo (43%), the material exhibits insulating behavior as indicated in Fig. 1c. It is believed that significant etching and loss of material continuity is responsible for the insulating behavior. Apparently, the oxidation that occurs during the atmospheric exposures, after sequential H2 plasma exposures, passivates the sulfur vacancies and slows the cumulative cation etching.

After a single cyclic exposure to H2 and O2 plasma (to emulate hydrogen plasma exposure followed by atmospheric oxidation), strong Mo6+ peaks are evident and S peaks are still exhibited. Peak fitting of the Mo 3d peaks reveal, the cumulative Mo content can be ascribed to MoS2 (17%), Mo5+ (22%), and Mo6+ (61%). In addition, all peaks are shifted to slightly higher binding energies, indicative of n-type doping, which is presumably due to sulfur vacancies in the MoS2 material remaining in the sample. The Mo6+ peak is indicative of extensive oxidation of the Mo; however, the remaining sulfur content suggests some residual MoS2. Recent work has shown that the generation of percolating edge states by defect engineering27 and oxidation of the edge of TMD flakes can result in metallic conduction.29 In addition, oxygen vacancies in sub-stoichiometric MoO3−x behave as n-type dopants, which can significantly increase the electrical conductivity of the material, and previous work has shown that sub-stoichiometric MoO3−x has states at the Fermi level.35 Here the hydrogen cycle of the cyclic plasma exposure generates S vacancies and the subsequent O2 plasma oxidizes the sulfur vacancies resulting in a heavily doped metallic-like layer of MoO3−x and oxidized edge states. Conveniently, the subsequent H2 and O2 plasma exposure enables the MoS2 flake to be modified via standard lithography and plasma processing to tune a resistor element into a single monolayer flake. This process enables a higher degree of control relative to the H2 plasma and subsequent oxidation in atmosphere.

Figure 3c shows the scanning transmission electron microscopic (STEM) images of MoS2 before (left) and after (right) a H2 → O2 plasma exposure. Notably, after the plasma exposure, the defect concentration is significantly increased, as indicated by the vacancies and pores found throughout the material. However, significant oxidation was not observed in the STEM images. This is likely because the MoO3−x can be volatilized at high vacuum, a phenomenon that has been noted in previous work.30 STEM images and XPS data support the claim that the cyclic plasma treatment effectively induces defects, which are subsequently oxidized. A large-area STEM image of the plasma-treated MoS2 can be found in Figure S5.

Figure 4a shows a schematic representative of the conversion of MoS2 to metallic MoO3−x. Before the plasma cycles, the FET consist of pristine MoS2 spanning between the source and drain with a 2-μm channel length. After plasma exposure and subsequent oxidation, the film is partially converted into non-continuous MoO3−x. Additional plasma cycles form a continuous percolating network of MoO3−x spanning between the source and drain that gives rise to the metallic behavior of the material, as shown in the right panel. This percolation of metallic MoO3−x is attributed to the steep decrease in sheet resistance and on/off ratio with >5 plasma cycles exhibited in Fig. 1. Specifically, the sheet-resistance (off-current) slowly lowers as portions of the MoS2 are converted to MoO3−x. Once a continuous percolating network of MoO3−x is formed (>5 cycles), a path is created for an electrical short between the source and drain. This results in a significant drop in sheet resistance and a complete reduction of the on/off ratio. In fact, similar behavior is exhibited when creating percolating conducting networks, for instance, of carbon nanotubes.36 Once a critical threshold of CNT concentration is exceeded, a continuous network results in a rapid increase in the electrical conductivity of many orders of magnitude.

Drain-induced barrier lowering (DIBL) for cyclic H2 plasma+atmosphere exposures. a Schematic showing the progressive formation of a percolating MoO3−x network with additional plasma+atmosphere cycles. Transfer curves for b pristine device and device after c 1 cycle of H2 plasma+atmosphere exposure. All devices have a 2-μm channel length. d DIBL as a function of plasma+atmosphere cycles. Error bars show standard error of the mean

As the MoS2 is progressively converted to MoO3−x, the effective channel length of the FET becomes reduced. The middle panel of Fig. 4a demonstrates this effect. Small portions of MoS2 suspended between percolating channels of MoO3−x can behave as short channels and exhibit short channel effects (SCEs). For example, drain-induced barrier lowering (DIBL, defined as ΔVth/ΔVSD) can occur when the electric field between the source and drain is sufficiently high to lower the barrier height of MoS2. This is manifested in higher off-currents for FETs and a shift in the threshold voltage with increasing source-drain voltage. The geometric screening length (λ) can be used to estimate the channel length at which SCEs will be exhibited. The geometric screening length is defined as:

where εTMD is the dielectric constant of MoS2 (~3.337), εox is the dielectric constant of SiO2, tTMDis the thickness of MoS2, tox is the oxide thickness, and SCEs are typically exhibited if the channel length is <2.5 × λ.38 For single-layer MoS2 on 290 nm SiO2, λ ~ 13 nm, indicating that SCEs, such as DIBL, are expected for channel lengths <33 nm.

Figure 4b, c show transfer curves for pristine MoS2 and MoS2 exposed to 1 cycle of H2 plasma/atmosphere (where 5 s of H2 plasma exposure cycles were used this time) at three different VDS values (0.1, 0.6, and 1.1 V) measured. The pristine MoS2 has a modest DIBL of ~4.7 V/V. With exposure to 1 cycle of H2 plasma/atmosphere the DIBL increases by >100% to a value of ~10.4 V/V. The effect of the plasma exposure plus atmosphere exposure cycles on the DIBL are shown in Fig. 4d. The DIBL correlates linearly with the number of cycles, and beyond 4 cycles (where LD = 2.67) the DIBL exceeded the VGS range used for the transfer curves. As the MoS2 is exposed to increasing number of cycles, an increase in DIBL reveals that the MoS2 → MoO3−x layer is growing, thus resulting in the formation of MoS2 short channels that are presumably <33 nm in width (2.5 × λ) between percolating MoO3−x. After 5 cycles of plasma+atmosphere exposure, there is a complete suppression gate modulation (Fig. 1d) and a sharp increase in the sheet resistance (Fig. 1e), indicating adequate conversion of the MoO3−x layer for percolation across the channel.

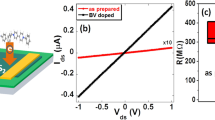

Plasma-induced defect generation and subsequent oxidation of the defects for metallic conduction can be applied in a lithographic manner to MoS2 to pattern novel devices from MoS2/MoO3−x lateral heterojunctions; however, extensive H2 plasma will rapidly etch carbon-based (poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA)) resist layers. Thus appropriate care must be taken to avoid over-etching the resist mask. To emulate the H2 plasma and atmospheric oxidation cycle, a cyclic H2 plasma → O2 plasma process (see XPS data in Fig. 3) was utilized to more controllably re-oxidize the sulfur vacancies generated by the H2 plasma. Specifically, an optimum 2s H2 plasma was followed by a 2s O2 plasma to achieve metallic conduction. By comparison, a comparable O2 plasma → H2 plasma process rapidly reduced MoS2 conductivity by presumably oxidizing and then reducing to effectively etch MoS2. This further demonstrates the importance of oxidation of the defect sites toward the generation of metallic conduction. Details about various cycle sequences of H2 and O2 plasmas for metallization can be found in Figure S3–S4.

To exploit the pseudo-metallic conduction (minimal gate modulation) that is exhibited with the generation of the MoO3−x, resistor-loaded inverters were created on a monolayer MoS2 flake. Figure 5a shows an optical image of a four-probe device (including back gate), which was created on a monolayer flake, that is composed of two FETs in series. After electrode deposition, the device was patterned with a PMMA-based electron beam resist to expose one channel. This channel was then exposed to the cyclic 2s H2 →2s O2 plasma process, as shown in the schematic of Fig. 5b, to induce the MoO3−x layer in the channel. Notably, the devices were fabricated on a 50-nm HfO2 gate dielectric in order to increase the gain of the inverter. Figure 5c shows a transfer curve for the portion of the device exposed to the cyclic plasma (black) as well as the portion that was masked by the PMMA during plasma exposure (red). The cyclic plasma exposure process significantly reduced the on/off ratio to ~102 while the masked device maintained an on/off ratio of >108. An on/off ratio of ~102 for the plasma-treated portion of the MoS2 was likely exhibited owing to slightly insufficient oxidation to create continuous percolating MoO3−x. The device exposed to the cyclic plasma effectively behaves as a resistor due to its significantly reduced on/off ratio. The input (VIN)–output (VOUT) characteristics for the resistor-loaded inverter are displayed in Fig. 5d and a circuit diagram is inset in the figure. VDD was varied from 1.5 to 2.0 V and VOUT was approximately the value for VDD. The threshold voltage for the inverter was slightly reduced for VDD = 2.0 V presumably due to modest on/off ratio of the plasma-treated portion. The voltage gain (dVOUT/dVIN) in the inverter is ~1 and can be further increased by reducing the thickness of the gate dielectric layer. This successfully demonstrates that metallic regions can be patterned in monolayer TMD flakes by a lithography-compatible cyclic plasma exposure. Other forms of atomically thin circuitry could be achieved with further optimization, such as edge-contact transistors and other more complex logic gates.

Lithographically patterned MoS2 inverter. a Optical image of lithographically patterned MoS2 inverter with one exposed channel. Scale bar is 5 μm. b Device structure showing one channel exposed to plasma to induce metallic conduction. c Transfer curves of the exposed and unexposed channel. d Input–output curves of resistor-loaded inverter

In summary, cycles of hydrogen and oxygen plasma are used to (1) create chalcogen vacancies in MoS2 and then (2) oxidize the vacancies. The MoS2 is lithographically converted to MoO3−x in a highly selective manner. This enables the formation of a lateral junction between semiconducting MoS2 and metallic MoO3−x. The cycles of plasma are applied to lithographically pattern a functioning resistor-loaded invertor in a single sheet of MoS2. This enables parallel processing to generate lateral semiconducting/metallic junctions, which are necessary for the formation of truly atomically thin circuits.

Methods

Material synthesis

MoS2 monolayers were synthesized through a chemical vapor deposition method conducted in a tube furnace system equipped with a 2” quartz tube. In a typical run, the growth substrates, e.g., Si with 285 nm SiO2 (SiO2/Si) substrates cleaned by acetone and isopropanol and coated with perylene-3,4,9,10-tetracarboxylic acid tetrapotassium salt as the growth seed, were placed face-down above an alumina crucible containing 0.5–1 mg of MoO3 powder, which was then inserted into the center of the quartz tube. Another crucible containing ~0.3 g of S powder was located at the upstream side of the tube. After evacuating the tube to ~5 × 10−3 Torr, the reaction chamber pressure was increased to ambient pressure through 500 sccm (standard cubic centimeter per minute) argon flow. Then the reaction was conducted at 700 °C (with a ramping rate of 30 °C/min) for 5 min with 80 sccm argon flow. At 700 °C in the center of the quartz tube, the temperature at the location of S powder was near 200 °C. After growth, the furnace was allowed to cool to room temperature.

Plasma exposures

The synthesized MoS2 was exposed to hydrogen and oxygen plasmas in this work. A 400-W inductively coupled remote H2 plasma was generated in an ALD system produced by Oxford Instruments; temperature was set to 150 °C and pressure to 200 mTorr with an H2 flow rate of 50 sccm. Oxygen plasmas were also generated using the same ALD system at a power of 100 W; temperature was set to 150 °C and pressure to 100 m Torr with an O2 flow rate of 100 sccm. Some MoS2 samples were subjected to atmospheric exposure after H2 plasma exposures. For these samples, each atmospheric exposure was 10 min in duration at atmospheric pressure. Relative humidity was approximately 50%, as controlled by the building ventilation.

Electrical characterization and device fabrication

MoS2 was synthesized on SiO2 (290 nm)/Si (heavily doped) wafers. Devices were fabricated using electron beam (E-beam) lithography. Electrodes were deposited using electron beam evaporation. The contacts were patterned via a lift-off process and consisted of Ti/Au (5/25 nm). Electrical properties were characterized with a probe station connected to an Agilent Tech B1500A semiconductor analyzer. The back-gate electrode for all devices reported in the work was the highly doped Si wafer.

Scanning transmission electron microscopy

STEM of the plasma-treated sample was performed at 120 kV with Cs probe correction on a NION UltraSTEM 200. Two consecutive 4k × 4k high-angle annular dark-field acquisitions were captured with ~0.3 Å pixel step size and 15 μs pixel dwell time. The two frames were used for scan aberration correction according to ref. 39, where the scan-corrected data of the first acquisition is presented in Fig. 3c. The image was additionally noise filtered by convolution of a 2-pixel sigma gaussian kernel. Holes in the MoS2 layer were evident for initial focus and low sampling/magnification scans and no additional holes appeared in the MoS2 layer between acquisitions indicating an origin other than STEM electron beam irradiation.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy

XPS data were collected using monochromatic Al Kα X-rays (1486.7 eV) at a pass energy of 26 eV in a PHI VersaProbe III UHV system, equipped with an auto dual-charge neutralizer. A spot size of 9 µm was used. Spectral deconvolution was carried out using the kolXPD software40 to fit the features observed in the Mo 3d and S 2p spectra and determine the chemical states present. Metallic Mo (elemental Mo0) peaks were fit with a Doniach–Sunjic lineshape41 convoluted with a Gaussian. All other peaks were fit with Voigt lineshapes.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Mak, K. F., Lee, C., Hone, J., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Atomically thin MoS2: a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 136805 (2010).

Radisavljevic, B., Radenovic, A., Brivio, J., Giacometti, V. & Kis, A. Single-layer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 147–150 (2011).

Chhowalla, M. et al. The chemistry of two-dimensional layered transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheets. Nat. Chem. 5, 263–275 (2013).

Jariwala, D., Sangwan, V. K., Lauhon, L. J., Marks, T. J. & Hersam, M. C. Emerging device applications for semiconducting two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. ACS Nano 8, 1102–1120 (2014).

Cheng, R. et al. Few-layer molybdenum disulfide transistors and circuits for high-speed flexible electronics. Nat. Commun. 5, 5143 (2014).

Radisavljevic, B., Whitwick, M. B. & Kis, A. Integrated circuits and logic operations based on single-layer MoS2. ACS Nano 5, 9934–9938 (2011).

Ross, J. S. et al. Electrically tunable excitonic light-emitting diodes based on monolayer WSe2 p-n junctions. Nat. Nano 9, 268–272 (2014).

Li, G. et al. All the catalytic active sites of MoS2 for hydrogen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 16632–16638 (2016).

Li, G. et al. Activating MoS2 for pH-universal hydrogen evolution catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 16194–16200 (2017).

Ling, X. et al. Parallel stitching of 2D materials. Adv. Mater. 28, 2322–2329 (2016).

Zhao, M. et al. Large-scale chemical assembly of atomically thin transistors and circuits. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 954–959 (2016).

Stanford, M. G., Rack, P. D. & Jariwala, D. Emerging nanofabrication and quantum confinement techniques for 2D materials beyond graphene. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2, 20 (2018).

Lin, Z. et al. Defect engineering of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. 2D Mater. 3, 022002 (2016).

Mahjouri-Samani, M. et al. Tailoring vacancies far beyond intrinsic levels changes the carrier type and optical response in monolayer MoSe2−x crystals. Nano. Lett. 16, 5213–5220 (2016).

Fox, D. S. et al. Nanopatterning and electrical tuning of MoS2 layers with a subnanometer helium ion beam. Nano Lett. 15, 5307–5313 (2015).

Stanford, M. G. et al. Focused helium-ion beam irradiation effects on electrical transport properties of few-layer WSe2: enabling nanoscale direct write homo-junctions. Sci. Rep. 6, 27276 (2016).

Stanford, M. G. et al. Tungsten diselenide patterning and nanoribbon formation by gas-assisted focused-helium-ion-beam-induced etching. Small Methods 1, 1600060 (2017).

Iberi, V. et al. Nanoforging single layer MoSe2 through defect engineering with focused helium ion beams. Sci. Rep. 6, 30481 (2016).

Ghorbani-Asl, M., Kretschmer, S., Spearot, D. E. & Krasheninnikov, A. V. Two-dimensional MoS2 under ion irradiation: from controlled defect production to electronic structure engineering. 2D Mater. 4, 025078 (2017).

Pudasaini, P. R. et al. High performance top-gated multilayer WSe2 field effect transistors. Nanotechnology 28, 475202 (2017).

Khondaker, S. I. & Islam, M. R. Bandgap engineering of MoS2 flakes via oxygen plasma: a layer dependent study. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 13801–13806 (2016).

Choudhary, N. et al. Two-dimensional lateral heterojunction through bandgap engineering of MoS2 via oxygen plasma. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 28, 364002 (2016).

Kang, N., Paudel, H. P., Leuenberger, M. N., Tetard, L. & Khondaker, S. I. Photoluminescence quenching in single-layer MoS2 via oxygen plasma treatment. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 21258–21263 (2014).

Islam, M. R. et al. Tuning the electrical property via defect engineering of single layer MoS2 by oxygen plasma. Nanoscale 6, 10033–10039 (2014).

Tosun, M. et al. Air-stable n-doping of WSe2 by anion vacancy formation with mild plasma treatment. ACS Nano 10, 6853–6860 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. Thermal oxidation of WSe2 nanosheets adhered on SiO2/Si substrates. Nano Lett. 15, 4979–4984 (2015).

Stanford, M. G. et al. High conduction hopping behavior induced in transition metal dichalcogenides by percolating defect networks: toward atomically thin circuits. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1702829 (2017).

Lu, J. et al. Atomic healing of defects in transition metal dichalcogenides. Nano Lett. 15, 3524–3532 (2015).

Addou, R. et al. One dimensional metallic edges in atomically thin WSe2 induced by air exposure. 2D Mater. 5, 025017 (2018).

Jadwiszczak, J. et al. Oxide-mediated recovery of field-effect mobility in plasma-treated MoS2. Sci. Adv. 4, eaao5031 (2018).

Lu, A.-Y. et al. Janus monolayers of transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 744 (2017).

Yamamoto, M. et al. Self-limiting layer-by-layer oxidation of atomically thin WSe2. Nano Lett. 15, 2067–2073 (2015).

Lee, C. H. et al. A self-limiting layer-by-layer etching technique for 2H-MoS2. Appl. Phys. Express 10, 35201 (2017).

Mignuzzi, S. et al. Effect of disorder on Raman scattering of single-layer MoS2. Phys. Rev. B 91, 195411 (2015).

Battaglia, C. et al. Hole selective MoOx contact for silicon solar cells. Nano Lett. 14, 967–971 (2014).

Li, J. et al. Correlations between percolation threshold, dispersion state, and aspect ratio of carbon nanotubes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 17, 3207–3215 (2007).

Yoon, Y., Ganapathi, K. & Salahuddin, S. How good can monolayer MoS2 transistors be? Nano Lett. 11, 3768–3773 (2011).

Xu, K. et al. Sub-10 nm nanopattern architecture for 2D material field-effect transistors. Nano Lett. 17, 1065–1070 (2017).

Ophus, C. & Ewalds, T. Guidelines for quantitative reconstruction of complex exit waves in HRTEM. Ultramicroscopy 113, 88–95 (2012).

Kolibrik.net. Custom develompent of electronics and software. Kolibrik.net (2017).

Doniach, S. & Sunjic, M. Many-electron singularity in X-ray photoemission and X-ray line spectra from metals. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 3, 285 (1970).

Acknowledgements

M.G.S. and P.D.R. acknowledge support by US Department of Energy (DOE) under Grant No. DOE DE-SC0002136. A.N.H. acknowledges support and the authors acknowledge the device fabrication and Raman analysis was performed at the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences, which is a DOE Office of Science User Facility. The material synthesis was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences (BES), Materials Sciences and Engineering Division. M.G.S. (UVA) acknowledges support through the UVA Engineering Distinguished Fellowship. The XPS used for this work was provided through the NSF-MRI Award #1626201. C.T.N. acknowledges support by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G.S. and P.D.R. conceived experiments. M.G.S. conducted plasma exposures, device fabrication, Raman characterization, and wrote the manuscript. A.N.H. conducted AFM microscopy. Y.-C.L. and K.X. synthesized the MoS2. M.G.S. (UVA) and S.M. conducted XPS and provided analysis. C.T.N. conducted STEM experiments. All authors contributed to data analysis and revisions of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stanford, M.G., Lin, YC., Sales, M.G. et al. Lithographically patterned metallic conduction in single-layer MoS2 via plasma processing. npj 2D Mater Appl 3, 13 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-019-0095-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-019-0095-5

This article is cited by

-

Evolution of defect formation during atomically precise desulfurization of monolayer MoS2

Communications Materials (2021)

-

Exploring the air stability of PdSe2 via electrical transport measurements and defect calculations

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2019)

-

Stable InSe transistors with high-field effect mobility for reliable nerve signal sensing

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2019)