Abstract

Radiative forcing (RF) time series for total ozone from 1850 up to the present day are calculated based on historical simulations of ozone from 10 climate models contributing to the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6). In addition, RF is calculated for ozone fields prepared as an input for CMIP6 models without chemistry schemes and from a chemical transport model simulation. A radiative kernel for ozone is constructed and used to derive the RF. The ozone RF in 2010 (2005–2014) relative to 1850 is 0.35 W m−2 [0.08–0.61] (5–95% uncertainty range) based on models with both tropospheric and stratospheric chemistry. One of these models has a negative present-day total ozone RF. Excluding this model, the present-day ozone RF increases to 0.39 W m−2 [0.27–0.51] (5–95% uncertainty range). The rest of the models have RF close to or stronger than the RF time series assessed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in the fifth assessment report with the primary driver likely being the new precursor emissions used in CMIP6. The rapid adjustments beyond stratospheric temperature are estimated to be weak and thus the RF is a good measure of effective radiative forcing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tropospheric ozone has increased since pre-industrial times primarily due to photochemical reactions involving components emitted to the atmosphere by anthropogenic activities1. Such emissions include methane (CH4), nitrogen oxides (NOx), carbon monoxide (CO), and non-methane volatile organic components (NMVOCs), collectively referred to as ozone precursors. In the stratosphere, the amount of ozone has decreased primarily due to anthropogenic emissions of ozone-depleting substances (ODSs)2.

Ozone is a greenhouse gas and considered as a “near-term climate forcer”3 due to its short global mean lifetime of ~23 days in the troposphere for the present day4. Hence, it is not well-mixed in the atmosphere and that challenges the estimation of the historical development of ozone in the atmosphere. There are limited long-term historical observations of ozone, in spatial coverage and in the vertical5,6,7,8. For climate impact calculations, the vertical distribution of ozone is crucial, as its effect on trapping thermal infrared radiation is largest in the upper troposphere9,10,11. Due to insufficient long-term observations, the time series of the historical development of ozone and its radiative forcing (RF) since pre-industrial times must be estimated using models.

Ozone is the third strongest anthropogenic greenhouse gas forcer assessed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in the fifth assessment report (AR5) with a total RF of 0.35 (0.15–0.55) W m−2 in 2011 relative to pre-industrial times (1750), where ozone changes in the troposphere are estimated to exert a RF of 0.40 (0.20–0.60) W m−2 and RF due to changes in stratospheric ozone of −0.05 (−0.15 to +0.05) W m−2 (5–95% uncertainty ranges)3. One of the main uncertainties in the estimates of tropospheric ozone RF is the incomplete knowledge of pre-industrial ozone concentrations12. The chemistry models have not been able to reproduce the low levels of ozone observed at the end of the nineteenth century12; however, those observations are highly uncertain7,8,13. A recent study puts forward a constraint on historical ozone levels using oxygen isotopes in ice cores and they concluded that historical ozone levels were in line with modeled ozone levels, and that early observations were biased low14.

Understanding past drivers of climate change is crucial for assessing future climate change. The climate models contributing to the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6)15 do not calculate the RF of the drivers by default. Separate initiatives under CMIP6, the Radiative Forcing Model Intercomparison Project (RFMIP)16, and the Aerosol and Chemistry Model Intercomparison Project (AerChemMIP)17 aim to give an accurate characterization of the effective RF (ERF) in the climate models and assess how anthropogenic emissions have contributed to global forcing over the historical period, respectively. The ERF includes rapid adjustments due to changes in atmospheric temperature, water vapor, and clouds without any response from surface temperature changes3,18,19 and goes beyond RF, which only includes the adjustment from stratospheric temperature3. ERF is the best measure to compare the global mean surface temperature change between different forcing mechanisms for perturbations to the Earth’s radiation budget, and in particular when the effect of the small land surface warming is removed in climate simulations keeping sea surface temperature constant20.

In this study, we calculate the historical time development of total ozone RF since 1850 from the Earth system models contributing to CMIP6 (Table 1). A radiative kernel is developed for total ozone RF by detailed radiative transfer code calculations on idealized ozone perturbations (see “Methods” section and Supplementary Fig. 1). This kernel is used to calculate the RF time series based on the modeled changes in ozone mixing ratios since the 1850s in the historical CMIP6 experiment. For those CMIP6 models without ozone chemistry schemes, ozone fields are provided through the input data sets for Model Intercomparison Projects (input4MIPs). In addition, we use the kernel to calculate the RF on these fields and compare the results with that of Checa-Garcia et al.21, who calculated RF on the input4MIPs ozone fields and the fields provided for the previous phase of CMIP. We focus on forcing due to total ozone changes, including both the effect of ozone increases due to ozone precursors and ozone decreases due to ODSs. Although these two effects mainly affect ozone in the troposphere and stratosphere, respectively, the two processes can have a substantial effect in the other region as well22,23. Ozone RF is often split into a tropospheric and stratospheric component3, but to split the RF based on the drivers (i.e., ozone precursors vs. ODSs) instead of the region in the atmosphere where the changes happen is more relevant for mitigation23. The RF calculated based on CMIP6 ozone fields is complemented with RF estimates based on simulations from a chemical transport model (CTM). Using the CTM results, RF is calculated due to changes in tropospheric ozone precursors only (ODSs changes excluded). In addition, RF is calculated in 1850 relative to 1750, to account for a different baseline, and the RF is extended up to 2020 (see “Methods” section).

Results

The vertical distribution of ozone is crucial for the RF calculations. In Fig. 1, the relative difference in annual zonal mean O3 between 1850 and 2010 is shown. The largest relative change in ozone over this period is found in the Northern Hemisphere (NH) troposphere, for the models that include tropospheric chemistry (all models, except the CNRM models). The increase is largest in the lower troposphere at mid-latitudes, with a tongue reaching up to the upper tropical troposphere where the relative increase for the models ranges from ~40 to ~80%. These are the regions with the largest ozone precursor emission sources24 and highest insolation, respectively. All models have an ozone reduction in the upper stratosphere and also in the lower stratosphere at the southernmost latitudes over Antarctica. The weakest maximum reduction in this region of 13% is found for the MRI-ESM2-0 model. The strongest ozone depletion is modeled by the UKESM1-0-LL model with a maximum reduction of 58%. This model is also the model with the weakest increase in tropospheric ozone, with an increase of 15–20% in the upper tropical troposphere in the Southern Hemisphere (SH), and it is likely to be that the ozone depletion has affected the troposphere to a larger extent in this model than for the other models. In other regions of the stratosphere, the sign of the change in ozone differs among the models. In particular, ozone depletion in the lower stratosphere at high northern latitudes is strong in some models, but less evident in other models for the annual means.

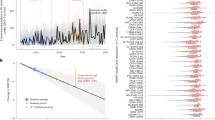

For the period before stratospheric ozone depletion, there is a large spread in the modeled total ozone column with ~60 Dobson Units (DU) difference in latitude bands between 60°S and 60°N for the annual mean and >100 DU difference in both polar regions during spring (Supplementary Fig. 2). At the end of the period, 2010, the simulated total ozone still has a large spread, but the values are lower. The temporal development also differs among the models. The largest decrease in ozone is seen for the UKESM1-0-LL model with the most rapid reduction between 1980 and 1990. In the GISS-E2-1-H model, total ozone increases from 1950 to 1980, with a rapid decrease thereafter. Ground-based measurements and satellite data are available from around 1980 for observations of total ozone25. Weber et al.25 estimated the trends in the observed total ozone prior to 1997 and from 1997 to 2016. In Fig. 2, these two trends are compared with the trends in the models from 1980 to 2000, and from 2000 to 2010. This is not an exact comparison, as the modeled data are averaged over 10 years. Most models have a negative trend for all regions over the period 1980–2000, whereas the models simulate a recovery post 2000, with trends closer to zero or above. This is the same feature as seen in the trend for the observations as estimated by Weber et al.25.

The period 1980–2000 to the left and the period 2000–2010 to the right, compared with the trend prior and post 1997 from Weber et al.25 using different merged data sets from satellite and ground-based observations for the period 1979–2016. The error bar indicates the 2σ trend uncertainty and does not include uncertainties due to possible drifts between the data sets and from the merging procedure.

Changes in ozone in the upper free troposphere produce stronger RF per DU change than ozone changes in the stratosphere and changes closer to the surface (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, there are limited observations available for evaluating the long-term trend of ozone in the troposphere, e.g., Oltmans et al.6 and Tarasick et al.7. The modeled ozone distribution for the year 2000 is compared with ozone sonde data in Supplementary Fig. 3. The models that include tropospheric chemistry are mostly within the range of the observations, indicating that seasonal cycle, latitudinal distribution, and vertical distribution of tropospheric ozone are well simulated. For ozone trends in the free troposphere, sonde data have been combined26,27,28 to generate the Trajectory-mapped Ozonesonde dataset for the Stratosphere and Troposphere (TOST) product. Gaudel et al.5 calculated trends over the period 1998 to 2012 using the TOST product for different latitude bands (shown in Fig. 3). The trend in TOST is close to zero between 30°S to 60°S similar to the trend in the models. In the northern extra tropics, a small positive trend is seen for the models that include tropospheric chemistry and for the TOST product. In the tropics, the TOST increase is larger than the modeled trends (30°S to 0 and 0 to 30°N). The largest increase in ozone in TOST was found after 2008 in the tropics, which we might not be able to capture due to the 10-year averages used in the figure. Ozone distribution and trends are influenced by internal natural variability including changes to the stratosphere–troposphere exchange29,30,31,32. The models simulate one possible climate realization and will not be able to reproduce observed inter-annual variability due to dynamical processes. A long time period is needed for tropospheric ozone trends assessment8. Also, Gaudel et al.5 compared the trend in TOST with trends in satellite-based product of tropospheric ozone. The products differ in the quantification of tropospheric ozone trends, both in sign and magnitude, and to determine why the trend in satellite products differ is a remaining issue5.

The relative change in tropospheric ozone (since 1850) in different latitude bands (a–e) and trend in tropospheric ozone 2000 to 2010 compared with the trend 1998 to 2012 in the TOST product5 (f–i). The error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals for the trend. The tropopause used for the models is the OsloCTM3 tropopause that is based on potential vorticity from the meteorological data generated by the Open IFS model at ECMWF. This definition differs from the one used in TOST, which is based on the WMO definition (2 K km−1 lapse rate) and individual models’ own definition. Models without tropospheric chemistry are indicated with a triangle.

The long-term trend in the modeled tropospheric ozone column is also shown in Fig. 3. The most rapid increase occurred between 1950 and 1980, prior to the period of good coverage in spatial and temporal scale of observations. The increase in ozone since 1850 is larger in the NH than in the SH. The increase in global tropospheric ozone since 1850 has a range of 40–60% for the models with tropospheric chemistry, except for the UKESM1-0-LL. The increase in the UKESM1-0-LL is ~24% since 1850, based on the tropopause diagnosed from the OsloCTM3 model (defined as potential vorticity of 2.5 potential vorticity unit, with upper limit 380 K potential temperature and lower limit of 5 km); this will differ from the tropopause definition used in other studies and in the individual models. However, Sellar et al.33 found a similar relative increase in tropospheric ozone of ~23% from a pre-industrial baseline for a different tropopause definition for UKESM1-0-LL. For comparison, in the Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Model Intercomparison Project the multi-model mean for tropospheric ozone increased by 41% in 2000 relative to 18504. With the exception of UKESM1-0-LL, the increase in tropospheric ozone in 2000 relative to 1850 is larger than 40% for all the models (Fig. 3).

Radiative forcing

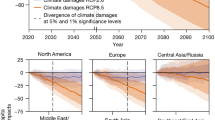

Figure 4 shows the kernel-derived total ozone forcing time evolution from the modeled changes in ozone since 1850 (base period 1850–59). The majority of the models show an increase in the forcing over the entire time period and the calculated RF time series are close to or, more frequently, above the best estimate of the RF time series in IPCC AR53 (Fig. 4). At the end of the time period (2010), the forcing is in the upper part of the range assessed by IPCC for total ozone RF in 2011 (Fig. 4). For the two CNRM models without tropospheric chemistry, the estimated RF in 2010 is −0.09 and −0.12 W m−2, within the range of ozone RF due to ODS assessed by IPCC AR53. The outlier of the models, which includes both tropospheric and stratospheric chemistry, is UKESM1-0-LL, with a negative total ozone forcing in 2010, only slightly weaker than the CNRM models without tropospheric chemistry. The ozone forcing in the UKESM1-0-LL model was weakly positive prior to 1990 and turned negative post 1990.

The total ozone RF are calculated using a radiative kernel on ozone fields for the historical experiment in CMIP6, the input4MIPs data and OsloCTM3 results. Also shown in the figure is the forcing time development calculated by Checa-Garcia et al.21 on the input4MIPs data, the total ozone forcing time series from IPCC AR5 relative to 1850, the total ozone RF range, and the range of ODS-caused ozone RF assessed by IPCC AR5 in 20113 adjusted to 1850 as the base period. Models without tropospheric chemistry are indicated with a triangle. The RF based on time-slice simulations using the OsloCTM3 is indicated by a square. The underlying numbers for this figure are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

Also shown in Fig. 4 are the forcing estimates of Checa-Garcia et al.21 using the input4MIPs data. It is noteworthy that the averaging periods in Checa-Garcia et al.21 are not the same as in this study, but the estimated RF for the input4MIPs data are similar to our values. In addition, if the RF calculation is split between long-wave and short-wave forcing, the trend is similar for the explicit RF calculations of Checa-Garcia et al.21 and for the kernel calculations in this study (Supplementary Figs 4 and 5). The short-wave RF is slightly stronger using the kernel compared with Checa-Garcia et al.21.

The temporal development of the RF since 1970 differs among the models (Fig. 4). For some models, the RF increases over the whole period (OsloCTM3, CESM-models, and BCC-ESM1). Some models have a flat or decreasing trend between 1980 and 1990 followed by an increase (GFDL-ESM4, input4MIPs, and E3SM-1-0, which used input4MIPs data in the troposphere). The GISS-E2-1-H and MRI-ESM2-0 models show an increase up to 1990. For the MRI-ESM2-0, the RF is constant thereafter, whereas GISS-E2-1-H has a renewed growth after 2000.

For OsloCTM3, the time period considered is extended both forward to 2020 (using IAMC-MESSAGE-GLOBIOM-ssp245 scenario emissions) and backwards to 1750. The RF in 1850 relative to 1750 is 0.03 W m−2, less than the 0.04 W m−2 from Skeie et al.34 adopted by Stevenson et al.12. For the period post 2010, the RF is 0.55 W m−2 in 2014, 0.54 W m−2 in 2017, and 0.56 W m−2 in 2020 relative to 1850. It is noteworthy that the OsloCTM3 model has the strongest total ozone RF and the value in 2010 (0.52 W m−2) is slightly above the upper range provided by IPCC AR5 (Fig. 4).

The RF between 2000 and 1850 from an additional simulation using OsloCTM3 with pre-industrial ODS in 2000 was 0.50 W m−2. The RF of 0.50 W m−2 due to changes in tropospheric ozone precursors is in the middle of the range assessed by the IPCC AR5 of 0.50 (0.30–0.70) W m−2 (5–95% uncertainty range) for ozone precursors3 and similar to the results of Søvde et al.22 (0.52 W m−2) and of Shindell et al.23 (~0.5 W m−2). Subtracting the RF from this simulation from the total ozone RF in OsloCTM3 gives an ozone RF of −0.06 W m−2 due to ODS, which is in the weaker part of the range assessed by the IPCC AR5 of −0.15 (−0.30 to 0.0) W m−2 (5–95% uncertainty range)3. For the two models that do not include tropospheric chemistry, ozone RF from ODSs is −0.13 W m−2 (CNRM-ESM2-1) and −0.08 W m−2 (CNRM-CM6-1) in 2000. The change is small in these two models for RF between 2000 and 2010 (Fig. 4). The OsloCTM3 RF and CNRM results for RF due to ODSs are in the weaker range of the IPCC AR5. Although not explicitly calculated, the ozone RF due to ODSs in UKESM1-0-LL is likely significantly stronger than in the OsloCTM3 and in the CNRM models.

Effective radiative forcing

The rapid adjustments other than stratospheric temperature adjustment are weaker than 0.1 W m−2 in a mean of simulations by three models (see “Methods”) using different sets of ozone fields adjusted to the present day (2014) relative to pre-industrial (1850). The adjustments from surface temperature, tropospheric temperature, surface albedo, water vapor, and clouds nearly cancel (each of the rapid adjustments are of ~0.1 W m−2 in magnitude or weaker). See Supplementary Fig. 6 for the rapid adjustment terms as a mean of the three models and different approaches for their quantification. The rapid adjustment calculations are within the uncertainties in these approaches and thus our RF estimates can be treated as similar to ERF.

Discussion

As CMIP6 model runs do not provide direct means of calculating time-varying RF due to anthropogenic changes in ozone, we calculate ozone forcing in this study based on the CMIP6 simulations over the historical period for those models that include tropospheric and/or stratospheric chemistry, using a radiative kernel. In addition, this study includes RF estimates using the OsloCTM3, a CTM driven by the same emission inventory as used in CMIP6, and RF estimates based on the ozone fields from input4MIPs prepared for CMIP6.

The full range of total ozone RF in 2010 (2005–2014) for models considering ozone changes in both troposphere and stratosphere is −0.064 W m−2 to 0.56 W m−2 relative to the 1850s. UKESM1-0-LL is the only model outside the range of AR5 for ozone and a clear outlier (see discussion below). Two models do not include tropospheric chemistry; hence, the ozone RF calculated is due to ODSs alone. These, as well as estimates from an additional simulation with the OsloCTM3, result in RF in the weaker part of the range assessed by IPCC AR5 for ozone changes due to ODSs. Similar to earlier findings from ODS-only simulations (which keep ozone precursor emissions constant), ozone decreases due to ODSs affect both the stratospheric and the tropospheric ozone burden22,23.

The UKESM1-0-LL model appears to have a much stronger ERF due to ODSs than many of the other models (Morgenstern et al., in review), although not explicitly calculated here. O’Connor et al.35 (revised version), e.g., report a present-day ERF from ODS of −0.18 W m–2 (including the direct radiative effect of the ODS themselves, the direct radiative effect of ozone, and other rapid adjustments) relative to the pre-industrial period. Given that previous estimates of the direct RF of ODS and ozone depletion are 0.36 W m–2 and −0.15 (−0.30 to 0.0) W m−2 (5–95% uncertainty range), respectively3, the offset by ozone depletion in UKESM1-0-LL appears to be too strongly negative. The study by Morgenstern et al. (in review) uses observed ozone trends from 1979 to 2000, to constrain the ERF due to ODSs from an ensemble of models and shows stronger ozone depletion in UKESM1-0-LL than observed, particularly in the SH. Using the tropospheric ozone kernel by Rap et al.36 on the UKESM1-0-LL model resulted in an RF in the lower range of IPCC AR5, similar to tropospheric RF calculated here if the stratosphere is masked (Supplementary Figs. 7a and 8a for two different definitions of the tropopause). This low estimate relative to IPCC AR5 may be due to the offset of −0.1 W m−2 from ODS on tropospheric ozone RF at the present day calculated by O’Connor et al.35, which is much stronger an effect from stratospheric ozone depletion than previous estimates (e.g., Søvde et al.22; Shindell et al.23). For the stratospheric ozone RF (Supplementary Figs. 7b and 8b), the UKESM1-0-LL is outside the range from IPCC AR53 and is consistent with the Morgenstern et al. study. There are indications that the ozone hole is too deep in UKESM1-0-LL, does not capture the observed inter-annual variability in ozone, and the negative trends in polar latitudes are too strong33. The model has larger ozone burden in Antarctic spring compared with the other CMIP6 models in the pre-industrial (Supplementary Fig. 2), whereas the OsloCTM3 with stratospheric ozone RF at and above the upper range of IPCC AR5 (Supplementary Figs. 7b and 8b) is the model with the lowest pre-industrial total ozone in the Antarctic spring (Supplementary Fig. 2). For the present day, the two models have modeled total ozone that is more similar to the rest of the models (Supplementary Fig. 2), but the magnitude in forcing differs. The main difference in total ozone is prior to the satellite era and it is hence difficult to exclude models, but we note UKESM1-0-LL as an outlier. UKESM1-0-LL is not able to reproduce the 1960–2000 surface temperature development33, although fixing ODS at 1950 levels, carried out as part of AerChemMIP17, does not have a large impact on the modeled global mean surface temperature behavior.

The multi-model mean for total ozone RF is 0.35 W m−2 with an SD of 0.16 W m−2 in 2010 (2005–2014) relative to 1850 (1850–1859) for the CMIP6 models (excluding the two models that do not include tropospheric chemistry), OsloCTM3 and input4MIPs (see Supplementary Table 2). This is 0.03 W m−2 stronger than what is calculated using input4MIPs data. Excluding, in addition, the outlier model, the multi-model mean estimate increases to 0.39 W m−2, 0.08 W m−2 stronger RF than calculated using the input4MIPs data only. The use of the kernel on input4MIPs ozone changes provides RF within 4% of the present-day total ozone RF (0.30 W m−2 for 2010–2014 relative to 1850–1860) in Checa-Garcia et al.21 using a different radiative transfer code on the same ozone fields. It is noteworthy that the time periods considered in Checa-Garcia et al.21 and this study differ.

Although the total RF calculated for the input4MIPs ozone field (0.31 W m−2) lies at the lower end of the CMIP6 range, it is similar to the AR5 mean (0.31 W m−2 relative to 1850). This can be explained by the input4MIPs ozone being a merger of two model simulations, which, for their historical simulations, included emissions following the Chemistry-Climate Model Initiative’s data protocol37. These emissions represent a merger of CMIP538 and RCP8.5 emissions, and not the official CMIP6 precursor emissions (which were not yet available at the time the input4MIPs database had to be prepared for CMIP6). On a global scale, the emission of NOx showed a rapid increase from 1990 to 2000, with ~15% higher anthropogenic emissions for the year 2000 in the CMIP6 emissions inventory compared with CMIP5, in which emissions remained stable from 1990 to 200024. As a consequence, CMIP6 precursor emissions result in global ozone changes that are fairly similar to those in input4MIPs up to the 1980s; however, they show a much stronger increase thereafter. The fact that the difference is mainly emission-driven can also be seen when comparing the input4MIPs ozone changes in Fig. 2 with those from CESM2(WACCM6), a slightly earlier version of which was used to derive the input4MIPs ozone. This also provides a possible explanation why most models driven by emissions of ozone precursors in CMIP6 have a higher RF compared with the IPCC AR5 best estimate3, which was heavily based on model simulations using the emission inventory of Lamarque et al.38, and a different time evolution post 1990. Post 1990, the RF based on the CESM2 models increases, whereas the RF based on the input4MIPs data are more stable (Fig. 4). Uncertainties in the historical emission inventories of tropospheric ozone precursors are not assessed in Hoesly et al.24, but assumed to be larger than the difference between the CMIP5 and CMIP6 emission inventories at the global scale, larger on the regional scale, and to increase back in time24. Uncertainties in the precursor emissions beyond the difference between CMIP5 and CMIP6 emissions are not considered in this study.

Finally, it is important to keep in mind that the spread in the total ozone RF as presented here are not based on results from 12 independent models. There are relationships among the models and the input4MIPs data (see Supplementary Table 1). CESM2(CAM6) uses prescribed ozone fields from a CESM2(WACCM6) simulation, BCC-ESM1 uses an earlier version of the chemistry scheme in CESM in the troposphere and input4MIPs data in the stratosphere, whereas E3SM-1-0 uses input4MIPs data in the troposphere. Also, the input4MIPs data are constructed using the chemistry schemes in an earlier version of the CESM(WACCM) model. If related models are excluded, the uncertainty range slightly increases (Supplementary Table 2).

Methods

Data

The climate models in CMIP6 include ozone in different ways for the historical simulations from 1850 up to the present day. Some models use prescribed ozone concentrations from the input4MIPs39, whereas other models include chemistry schemes, but they vary in complexity. Mainly, chemistry schemes in the models are either developed for the whole atmosphere, only for the troposphere or only for the stratosphere. In this study, we use a radiative kernel (see below) to calculate RF since 1850. We include the models that have uploaded monthly ozone fields to the CMIP6 database for the historical experiment, except those that use the ozone fields provided by input4MIPs and NorESM, which uses the same ozone input fields as CESM2(CAM6) and GISS-E2-1-G, which is identical to GISS-E2-1-H, except a different ocean model. Kernel ozone RF results for the models using input4MIPs, the NorESM compared with CESM2(CAM6), and GISS-E2-1-G compared with GISS-E2-1-H are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. An overview of the models included in this study is presented in Table 1. When several ensemble members are available, one member is chosen (Table 1). Total ozone RF is also calculated based on the ozone fields provided by input4MIPs and results from a CTM40 using the historical emission inventories prepared for CMIP624,41.

Chemical transport model

The CMIP6 simulations are supplemented by time-slice simulations using the Oslo Chemistry transport model (OsloCTM3)40,42. It is a three-dimensional chemistry transport model driven by three-hourly meteorological forecast data by the Open Integrated Forecast System (Open IFS, cycle 38 revision 1) at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts. The horizontal resolution is ~2.25° × 2.25° with 60 vertical layers ranging from the surface up to 0.1 hPa.

Time-slice simulations are performed for the years 1750, 1850, 1950, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010, 2014, 2017, and 2020, but with fixed year 2010 meteorological data for all simulations. For the year simulated, historical anthropogenic emissions are from Hoesly et al.24 and biomass burning emissions from van Marle et al.41, while natural emissions are kept constant. For the year 2017 and 2020, gridded emissions using the IAMC-MESSAGE-GLOBIOM-ssp245 scenario43 are used. A linear interpolation between 2015 and 2020 is assumed for 2017 emissions. The upper boundary conditions are taken from simulations done with the Oslo 2D model and the surface concentration of methane is scaled to observed concentration. Spin up is 1 year and the concentrations of long-lived components from the restart files used for initialization are scaled to historical values. Year 1850 is used as baseline in the forcing calculations. Forcing calculations for OsloCTM3 are also performed for the period between 1750 and 1850. It is noteworthy that the OsloCTM3 results are snapshots rather than the 10-year averages used for the CMIP6 results. An additional simulation with year 2000 emissions and pre-industrial stratospheric ODS concentrations is performed to isolate the forcing due to tropospheric ozone precursors.

The radiative kernel

A radiative kernel is constructed using a radiative transfer model, perturbing ozone in one model layer at a time, giving gridded monthly fields of RF per DU change (Supplementary Fig. 1). The radiative transfer code44 consists of a broadband code for long-wave radiation45 and the DIScrete Ordinate Radiative Transfer code for short-wave radiation46. The RF (all-sky) of total ozone changes is quantified at the tropopause, with stratospheric temperature adjustment. When stratospheric temperature adjustment is included, the RF at the tropopause will be similar to the forcing at the top of the atmosphere. The stratospheric temperature adjustment is calculated using the fixed dynamical heating approach, during an iterative process, taking short-wave and long-wave radiation into account47. The temperature changes from this iterative process will differ with altitude at the various model layers in the stratosphere. Meteorological fields of temperature, water vapor, and clouds are taken from the Integrated Forecast System of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts for year 2003 and applied as monthly mean fields. RF of well-mixed greenhouse gases using monthly data is within 1% of daily simulations45. The difference using the radiative kernel and the radiative transfer model applied for generating the kernel applying the OsloCTM3 ozone change is 0.001 W m−2 for both short-wave and long-wave radiation.

RF calculations

A radiative kernel is used for the RF calculation. The CMIP6 model results and input4MIPs ozone fields are bilinearly interpolated onto a T21 grid (~5.6° × 5.6°) and linearly interpolated in pressure to 60 vertical levels (ranging from the surface and up to 0.1 hPa), which is the resolution of the radiative kernel. Values in levels above the model top (Supplementary Table 1) are set to zero. To eliminate natural variability, 10-year averages are calculated. The time periods considered are 1850 (1850–1859) as the reference period for the forcing calculations, 1920 (1916–1925), 1930 (1926–1935), 1940 (1936–1945), 1950 (1946–1955), 1960 (1956–1965), 1970 (1966–1975), 1980 (1976–1985), 1990 (1986–1995), 2000 (1996–2005), 2007 (2003–2012), and 2010 (2005 to 2014). These 10-year averages of the mixing ratios are used in radiative kernel. To convert to DUs, the atmospheric fields from the OsloCTM3 are used. All results presented in this manuscript are for these interpolated and averaged model results, but with a horizontal distribution of T42 (~2.8° × 2.8°) for ozone field figures. As for the CMIP6 model results, the CTM results are interpolated to the T21 grid for the kernel calculations and T42 resolutions for the ozone field figures.

Effective radiative forcing

The rapid adjustment calculations other than stratospheric temperature adjustment are taken from two sources; offline calculations from the GFDL model as an additional simulation using setup as in RFMIP16 and simulations from the Precipitation Driver Response Model Intercomparison Project (PDRMIP)48 using the two models NorESM1 and MIROC-SPRINTARS. The estimates of rapid adjustments in the two PDRMIP models follow the approach in Smith et al.49 and Myhre et al.50, whereby the radiative kernel technique51 is applied to fixed sea surface temperature simulations. In this method, individual rapid adjustments are diagnosed by multiplying temperature, water vapor, and surface albedo radiative kernels by the model’s simulated change in those variables. Cloud rapid adjustments are diagnosed from change in cloud RF corrected for cloud masking using the non-cloud radiative kernels. This accounts for the fact that change in cloud RF includes not only cloud rapid adjustments but the radiative differences in non-cloud rapid adjustments under all-sky vs. clear-sky conditions. For added robustness, estimates are conducted with five different sets of radiative kernels49,51,52,53, including one set where water vapor and cloud adjustments are alternatively estimated using a partial radiative perturbation approach. This is a more direct but more computationally intensive method than radiative kernels where offline radiative transfer calculations are conducted on the base state of the model, while rapid adjustment variables from the perturbed forcing simulation are substituted into the calculation one at a time. The RFMIP calculations include ozone changes from pre-industrial (1850) to present-day and PDRMIP calculations apply a large perturbation of ten times anthropogenic changes to ozone into the lower part of the atmosphere from MacIntosh, et al.54 for NorESM1 and a five times anthropogenic emissions in MIROC-SPRINTARS.

Data availability

The radiative kernel is available at https://github.com/ciceroOslo/Radiative-kernels. The OsloCTM3 results and the results from the Kernel calculations are openly available via the NIRD Research Data Archive https://doi.org/10.11582/2020.00030. The CMIP6 model results and input4MIPs ozone fields are available at the Earth System Grid Federation (https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/cmip6/).

References

Monks, P. S. et al. Tropospheric ozone and its precursors from the urban to the global scale from air quality to short-lived climate forcer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 8889–8973 (2015).

WMO (World Meteorological Organization). Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2018, Global Ozone Research and Monitoring Project. Report No. 58. 588 (World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2018).

Myhre, G. et al. in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013).

Young, P. J. et al. Pre-industrial to end 21st century projections of tropospheric ozone from the Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Model Intercomparison Project (ACCMIP). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 2063–2090 (2013).

Gaudel, A. et al. Tropospheric Ozone Assessment Report: present-day distribution and trends of tropospheric ozone relevant to climate and global atmospheric chemistry model evaluation. Elem. Sci. Anth. 6, 39 (2018).

Oltmans, S. J. et al. Recent tropospheric ozone changes – a pattern dominated by slow or no growth. Atmos. Environ. 67, 331–351 (2013).

Tarasick, D. et al. Tropospheric Ozone Assessment Report: Tropospheric ozone from 1877 to 2016, observed levels, trends and uncertainties. Elem. Sci. Anth. 7, 39 (2019).

Cooper, O. R. et al. Global distribution and trends of tropospheric ozone: an observation-based review. Elem. Sci. Anth. 2, 000029 (2014).

Forster, P. M. D. & Shine, K. P. Radiative forcing and temperature trends from stratospheric ozone changes. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 10841–10855 (1997).

Lacis, A. A., Wuebbles, D. J. & Logan, J. A. Radiative forcing of climate by changes in the vertical distribution of ozone. J. Geophys. Res. 95, 9971–9981 (1990).

Hansen, J., Sato, M. & Ruedy, R. Radiative forcing and climate response. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 6831–6864 (1997).

Stevenson, D. S. et al. Tropospheric ozone changes, radiative forcing and attribution to emissions in the Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Model Intercomparison Project (ACCMIP). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 3063–3085 (2013).

Pavelin, E. G., Johnson, C. E., Rughooputh, S. & Toumi, R. Evaluation of pre-industrial surface ozone measurements made using Schonbein’s method. Atmos. Environ. 33, 919–929 (1999).

Yeung, L. Y. et al. Isotopic constraint on the twentieth-century increase in tropospheric ozone. Nature 570, 224–227 (2019).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Pincus, R., Forster, P. M. & Stevens, B. The Radiative Forcing Model Intercomparison Project (RFMIP): experimental protocol for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3447–3460 (2016).

Collins, W. J. et al. AerChemMIP: quantifying the effects of chemistry and aerosols in CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 585–607 (2017).

Boucher, O. et al. in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013).

Sherwood, S. C. et al. Adjustments in the forcing-feedback framework for understanding climate change. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 96, 217–228 (2015).

Richardson, T. B. et al. Efficacy of climate forcings in PDRMIP models. J. Geophys. Res. 124, 12824–12844 (2019).

Checa-Garcia, R., Hegglin, M. I., Kinnison, D., Plummer, D. A. & Shine, K. P. Historical tropospheric and stratospheric ozone radiative forcing using the CMIP6 database. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 3264–3273 (2018).

Søvde, O. A., Hoyle, C. R., Myhre, G. & Isaksen, I. S. A. The HNO3 forming branch of the HO2 + NO reaction: pre-industrial-to-present trends in atmospheric species and radiative forcings. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 8929–8943 (2011).

Shindell, D. et al. Attribution of historical ozone forcing to anthropogenic emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 567–570 (2013).

Hoesly, R. M. et al. Historical (1750–2014) anthropogenic emissions of reactive gases and aerosols from the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS). Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 369–408 (2018).

Weber, M. et al. Total ozone trends from 1979 to 2016 derived from five merged observational datasets – the emergence into ozone recovery. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 2097–2117 (2018).

Tarasick, D. W. et al. High-resolution tropospheric ozone fields for INTEX and ARCTAS from IONS ozonesondes. J. Geophys. Res. 115, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JD012918 (2010).

Liu, J. et al. A global ozone climatology from ozone soundings via trajectory mapping: a stratospheric perspective. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 11441–11464 (2013).

Liu, G. et al. A global tropospheric ozone climatology from trajectory-mapped ozone soundings. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 10659–10675 (2013).

Liu, J. et al. Origins of tropospheric ozone interannual variation over Réunion: A model investigation. J. Geophys. Res. 121, 521–537 (2016).

Lin, M., Horowitz, L. W., Oltmans, S. J., Fiore, A. M. & Fan, S. Tropospheric ozone trends at Mauna Loa Observatory tied to decadal climate variability. Nat. Geosci. 7, 136–143 (2014).

Hess, P., Kinnison, D. & Tang, Q. Ensemble simulations of the role of the stratosphere in the attribution of northern extratropical tropospheric ozone variability. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 2341–2365 (2015).

Hsu, J. & Prather, M. J. Stratospheric variability and tropospheric ozone. J. Geophys. Res. 114, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JD010942 (2009).

Sellar, A. A. et al. UKESM1: description and evaluation of the UK Earth System Model. J. Adv. Model Earth Syst. 11, 4513–4558 (2019).

Skeie, R. B. et al. Anthropogenic radiative forcing time series from pre-industrial times until 2010. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 11827–11857 (2011).

O’Connor, F. M. et al. Assessment of pre-industrial to present-day anthropogenic climate forcing in UKESM1. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 2020, 1–49 (2020).

Rap, A. et al. Satellite constraint on the tropospheric ozone radiative effect. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 5074–5081 (2015).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of IGAC/SPARC Chemistry-Climate Model Initiative (CCMI) community simulations in support of upcoming ozone and climate assessments. SPARC Newslett. 40, 48–66, http://www.sparc-climate.org/fileadmin/customer/6_Publications/Newsletter_PDF/40_SPARCnewsletter_Jan2013_web.pdf (2013).

Lamarque, J. F. et al. Historical (1850–2000) gridded anthropogenic and biomass burning emissions of reactive gases and aerosols: methodology and application. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 7017–7039 (2010).

Hegglin, M. I., Kinnison D., Lamarque, J. -F. & Plummer, D. CCMI ozone in support of CMIP6 - version 1.0, https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/INPUT4MIPS.1115 (2016).

Søvde, O. A. et al. The chemical transport model Oslo CTM3. Geosci. Model Dev. 5, 1441–1469 (2012).

van Marle, M. J. E. et al. Historic global biomass burning emissions for CMIP6 (BB4CMIP) based on merging satellite observations with proxies and fire models (1750–2015). Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 3329–3357 (2017).

Lund, M. T. et al. Concentrations and radiative forcing of anthropogenic aerosols from 1750 to 2014 simulated with the Oslo CTM3 and CEDS emission inventory. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 4909–4931 (2018).

Fricko, O. et al. The marker quantification of the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 2: a middle-of-the-road scenario for the 21st century. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 251–267 (2017).

Myhre, G. et al. Radiative forcing due to changes in ozone and methane caused by the transport sector. Atmos. Environ. 45, 387–394 (2011).

Myhre, G. & Stordal, F. Role of spatial and temporal variations in the computation of radiative forcing and GWP. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 11181–11200 (1997).

Stamnes, K., Tsay, S. C., Wiscombe, W. & Jayaweera, K. Numerically stable algorithm for discrete-ordinate-method radiative-transfer in multiple-scattering and emitting layered media. Appl. Opt. 27, 2502–2509 (1988).

Fels, S. B., Mahlman, J. D., Schwarzkopf, M. D. & Sinclair, R. W. Stratospheric sensitivity to perturbations in ozone and carbon dioxide: radiative and dynamical response. J. Atmos. Sci. 37, 2265–2297 (1980).

Myhre, G. et al. PDRMIP: a precipitation driver and response model intercomparison project—protocol and preliminary results. B. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 98, 1185–1198 (2016).

Smith, C. J. et al. Understanding rapid adjustments to diverse forcing agents. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 12,023–012,031 (2018).

Myhre, G. et al. Quantifying the importance of rapid adjustments for global precipitation changes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 11,399–311,405 (2018).

Soden, B. J. et al. Quantifying climate feedbacks using radiative kernels. J. Clim. 21, 3504–3520 (2008).

Pendergrass, A. G., Conley, A. & Vitt, F. M. Surface and top-of-atmosphere radiative feedback kernels for CESM-CAM5. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 317–324 (2018).

Shell, K. M., Kiehl, J. T. & Shields, C. A. Using the radiative kernel technique to calculate climate feedbacks in NCAR’s community atmospheric model. J. Clim. 21, 2269–2282 (2008).

MacIntosh, C. R. et al. Contrasting fast precipitation responses to tropospheric and stratospheric ozone forcing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 1263–1271 (2016).

Wu, T. et al. Beijing Climate Center Earth System Model version 1 (BCC-ESM1): model description and evaluation of aerosol simulations. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 977–1005 (2020).

Danabasoglu, G. et al. The Community Earth System Model Version 2 (CESM2). J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019MS001916 (2020).

Gettelman, A. et al. The Whole Atmosphere Community Climate Model Version 6 (WACCM6). J. Geophys. Res. 124, 12380–12403 (2019).

Voldoire, A. et al. Evaluation of CMIP6 DECK experiments With CNRM-CM6-1J. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 2177–2213 (2019).

Michou, M. et al. Present-day and historical aerosol and ozone characteristics in CNRM CMIP6 simulations. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019MS001816 (2019).

Séférian, R. et al. Evaluation of CNRM Earth-System model, CNRM-ESM 2-1: role of Earth system processes in present-day and future climate. J. Adv. Model Earth Syst. 11, 4182–4227 (2019).

Rasch, P. J. et al. An overview of the atmospheric component of the energy exascale Earth system model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 2377–2411 (2019).

Golaz, J.-C. et al. The DOE E3SM Coupled Model Version 1: overview and evaluation at standard resolution. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 2089–2129 (2019).

Krasting, J. P. et al. NOAA-GFDL GFDL-ESM4 model output prepared CMIP6 CMIP. https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.1407 (2018).

Yukimoto, S. et al. The Meteorological Research Institute Earth System Model Version 2.0, MRI-ESM2.0: description and basic evaluation of the physical component. J. Meteorological Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 97, 931–965 (2019).

Archibald, A. T. et al. Description and evaluation of the UKCA stratosphere–troposphere chemistry scheme (StratTrop vn 1.0) implemented in UKESM1. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 1223–1266 (2020).

Shindell, D. T. et al. Interactive ozone and methane chemistry in GISS-E2 historical and future climate simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 2653–2689 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the World Climate Research Programme, which, through its Working Group on Coupled Modelling, coordinated and promoted CMIP6. We thank the climate modeling groups for producing and making available their model output, the Earth System Grid Federation (ESGF) for archiving the data and providing access, and the multiple funding agencies who support CMIP6 and ESGF. R.B.S. and G.M. were funded through the Norwegian Research Council project KEYCLIM (grant number 295046) and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement 820829 (CONSTRAIN). D.S. acknowledges support from NASA-GISS and the NASA Center for Climate Simulation. F.M.O.C. and A.S. acknowledge funding from the Met Office Hadley Centre Climate Programme funded by BEIS and Defra (GA01101). F.M.O.C. also acknowledges the EU Horizon 2020 Research Programme CRESCENDO project, grant agreement number 641816. M.D. was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (grant numbers: JP20K04070). R.K. acknowledges support from an appointment to the NASA Postdoctoral Program at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, administered by Universities Space Research Associated. The CESM project is supported primarily by the National Science Foundation (NSF). This material is based upon work supported by the National Center for Atmospheric Research, which is a major facility sponsored by the NSF under Cooperative Agreement Number 1852977. The work of P.J.C.-S. was performed at LLNL under Contract DE-AC52-07NA27344 and was supported as part of the E3SM project funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and used resources of the NERSC Computing Center, which is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract Number DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.B.S. led the work and wrote the paper. G.M. had the original idea and contributed with ERF calculations. Ø.H. did the simulations for constructing the Radiative Kernel. R.B.S. performed the CTM simulations and the kernel calculations. D.J.L.O., D.P., T.T., B.H.S., and R.K. contributed with simulations for ERF calculations. P.J.C.-S., M.D., L.W.H., M.M., M.J.M., F.M.O.C., A.S., D.S., and T.W. contributed with CMIP6 ozone fields. M.I.H. contributed with the input4MIPs ozone fields. All authors gave input in the writing process.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Skeie, R.B., Myhre, G., Hodnebrog, Ø. et al. Historical total ozone radiative forcing derived from CMIP6 simulations. npj Clim Atmos Sci 3, 32 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-020-00131-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-020-00131-0

This article is cited by

-

A multi-model assessment of the Global Warming Potential of hydrogen

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)

-

Predicting habitat suitability of Litsea glutinosa: a declining tree species, under the current and future climate change scenarios in India

Landscape and Ecological Engineering (2023)

-

Quantifying contributions of ozone changes to global and arctic warming during the second half of the twentieth century

Climate Dynamics (2023)

-

Stratospheric ozone, UV radiation, and climate interactions

Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences (2023)

-

Chemistry-driven changes strongly influence climate forcing from vegetation emissions

Nature Communications (2022)