Abstract

The use of research evidence (URE) in policy and practice is relevant to many academic disciplines, as well as policy and practice domains. Although there has been increased attention to how such evidence is used, those engaged in scholarship and practice in this area face challenges in advancing the field. This paper attempts to “map the field” with the objective of provoking conversation about where we are and what we need to move forward. Utilizing survey data from scholars, practitioners, and funders connected to the study of the use of research evidence, we explore the extent to which URE work span traditional boundaries of research, practice, and policy, of different practice/policy fields, and of different disciplines. Descriptive and network analyses point to the boundary spanning and multidisciplinarity of this community, but also suggest exclusivity, as well as fragmentation among disciplines and literatures on which this work builds. We conclude with opportunities for to improve the connectedness, inclusiveness, relationship to policy and practice, and sustainability of URE scholarship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of research evidenceFootnote 1 (URE) in policy and practice is relevant to many academic disciplines; and indeed many policy and practice domains (Oliver and Boaz, 2019). Different methods and approaches to measuring, evaluating, promoting and describing the various ways in which evidence and policy/practice interact have sprung up (Gitomer and Crouse, 2019; Lawlor et al., 2019; Pedersen et al., 2020), reflecting the broad and diverse areas where this is a concern. There has also been an explosion of research into how such evidence is produced and used, with dedicated journals and increased funding for URE work emerging over last 15 years (see, e.g., Smith et al., 2019; Duncan and Oliver, 2019). Yet at the same time, those engaged in the scholarship and practice of URE face challenges advancing the field in terms of both accumulation of knowledge over time and across disciplines, and intervention and improvement in evidence use.

Our shared interest in advancing URE and its efforts, in collaboration with the William T. Grant Foundation, brought us together to “map the field”, with the objective of provoking a conversation about where we are and what we need to move forward. Our initial aim was to map the community of scholars, practitioners and funders directly connected with the study of URE. This exercise demonstrated two things. Firstly, most academic disciplines have a community of scholars working on this set of problems (Oliver and Boaz, 2019). These are not connected into a wider multi-disciplinary community, in part because each discipline has its own terminology and way of referring to the problem (e.g., ‘meta-science’ in neurobiology; ‘use of research evidence’ in education and social policy). This mitigates against easy conversation and collaboration between disciplinary scholars, and hinders development of this specialized area of research, leaving (particularly early career) researchers to relearn the same lessons over and over again.

Secondly, this demonstrated that there is a larger universe of scholars, funders, practitioners and policymakers who are either studying evidence production and use, putting into practice this knowledge, or funding and supporting research in this area. This larger universe remains unmapped. Mapping a field has the power to reveal the organization and structure of the scholarship and provide direction for its growth and sustainability (Beal et al., 1986; Rogers, 1995; Lievrouw, 1989). Although there have been attempts to identify this community (Nyanchoka et al., 2019; Pedersen et al., 2020; Waltman et al., 2019), these approaches have relied on bibliometric mapping and/or remain within academic disciplines. We believe that there is a clear need to map all those doing and supporting URE research, and those using this knowledge in practice, in order to know where to build links and between whom. This paper, however, focuses on an initial mapping exercise which explores the work and networks of those studying the use of research evidence. We close with a number of recommendations about how to build this community, and how to maximize the existing learning and work together to identify new, genuine knowledge gaps about how we make, find and use evidence.

Background and context

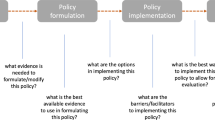

URE has its roots in knowledge utilization, which Backer (1991) describes as, “research, scholarly, and programmatic intervention activities aimed at increasing the use of knowledge to solve human problems (p. 226)” such as education, employment and healthcare. Importantly, the core components of the field—“evidence” and “use”—are broadly construed, incorporating a range of types of evidence, inclusive of research, and constituting varied forms and purposes as ‘use’, such as the categories of instrumental, conceptual, political/strategic, and symbolic commonly featured in evidence use scholarship (Weiss, 1979). The study of URE, is, at its core, focuses on understanding the formation of policy and practice and the role(s) evidence has in that process. In effect, this includes inquiry into how decisions are made; how research outputs reach decision-makers and how they respond to them; but also the rest of the research life-cycle. How are evidence bases created? What is funded, and how? Who in involved in setting research priorities, when and why; and in the production, interpretation and mobilization of knowledge?

Historically, the study of URE has come in and out of focus, peaking in the 1970s and early 1980s, a period during which many seminal works were produced and published in journals such as Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion, and Utilization, as well as in flagship journals such as Administrative Science Quarterly. The last 20 years have also seen the re-emergence of evidence use as a focus of inquiry; this time, explicitly recognizing the importance of the connections between how evidence is produced (through funding, research practices, partnerships and infrastructures), and how it is used (communicated, disseminated, received and responded to). In practical terms, this can be seen in the re-establishment of venues for scholarship, such as Evidence and Policy, the U.K’s What Works Centres, the U.S. Institute for Education Sciences’ investment in two knowledge utilization centers, and philanthropic support for the study of evidence use by the William T. Grant Foundation.

Alongside these practical investments, there has been a widening recognition that the core concerns of the URE community are shared by other scholars (Oliver and Boaz, 2019; Tseng, 2012; Tseng and Coburn, 2019). The study of the production of evidence has been generally undertaken under the broad umbrellas of science policy, research assessment or evaluation, and science and technology studies (see, e.g., Waltman et al., 2019; Ioannidis et al., 2015; Munafò et al., 2017; Jasanoff, 2004; Watermeyer, 2014), whereas the study of use has belonged to the more applied social sciences (e.g., health and education; see Boaz et al., 2019a; Bauer et al., 2015; Bransford et al., 2009; Finnigan and Daly, 2014). There are of course exceptions to this rule, such as the study of innovation and technology transfer within the STS community, and the engaged research movement (Nightingale, 1998; Holliman, 2019). Yet the community of scholars working on these problems have always recognized that there are links between the production and use of knowledge. For example, both camps recognize that research is more likely to be used/implemented/acted on if users are involved in setting research priorities (e.g., Thornicroft et al., 2002; Acworth, 2008; Martin, 2010; Nolan et al., 2007; Penuel et al., 2015; Van der Meulen, 1998). But until recently there have been few attempts to join these different disciplines in a way which satisfyingly exploits what we can learn from these different perspectives. There have been recent attempts to engage with this interdisciplinary community through conferences and institutes aiming to tackle the ‘emerging field’ of meta-science, research-on-research, and other variations on a similar theme (Oliver and Boaz, 2019).

Of course, the study of how evidence is produced and used is hardly ‘emerging’. Indeed, scholars and practitioners from fields as diverse as computer science to clinical medicine; from conservation to art history have made, and continue to make contributions to this field (see, e.g., Feyerabend, 1961; Mukerji, 2001; Parkhurst, 2017). The tendency to claim this as a new field means that we are both failing to learn from each other, and seeing this learning itself as an unimportant task. There is a danger that we will promise collaborators that there are new, quick fixes to the old, complex problems which are inherent in the relationship between evidence, policy and practice (see, e.g., French, 2018; Haskins, 2018). For funders in particular, the promise of a transformative new approach that will maximize research impact can feel too good an opportunity to miss. As a consequence, opportunities for thinking and learning across disciplines to tackle thorny problems are repeatedly lost. We have to be honest about what this means for the quality of scholarship in this area.

However, the diversity in the field is potentially a huge strength, bringing in theoretical perspectives, methods, approaches which help us to find new perspectives on the complex problem of evidence use. Yet there are also challenges. We have no way to describe this larger universe of funders, scholars, practitioners and policymakers; we struggle to find each other as a community, as such an inherently multi-disciplinary or inter-disciplinary field of study will rarely meet at conferences or virtually. We use different language to talk about what we do and how, and we promote our work in different spaces. We may replicate each other’s work, or solve the same problems over and over again, seldom realizing that we are working in parallel. This work is carried on in different geographies, disciplines, sectors and policy domains. But we have as yet no clear way to cross the boundaries.

Improving the use of evidence is one of the major policy and practice challenges of our age (Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking, 2017). We have more data available to us, and researchers are better equipped and more outward facing than ever before (Boaz et al., 2019b). Populations hold their governments to account, and researchers are under pressure to demonstrate the impact and public value of what they do. Ethically, morally, and practically, we should, as a community, learn better from each other, and take our lessons back to our home disciplines. To do this, it is imperative that those working on this set of related problems learn from each other more effectively. A first step in this process is to identify the different scholarly communities working on this set of problems, and characterize them and their discourses.

In this paper, we share our exploration of a scholarly community that emerged from the leadership of a foundation, conducted as a means to preliminarily map the URE community, and identify opportunities for expansion and coordination amongst the wider community. Specifically, we sought to better understand the strengths and challenges facing the URE community by answering the following questions: To what extent does URE span traditional boundaries of research, practice, and policy? Of different practice/policy fields? Of different disciplines?

We acknowledge this work represents only a partial view of the larger URE space, as will be evident in our data below, but also believe it is illustrative of the challenges facing the larger scholarly community and can serve to foster broader discussion and debate about the future of URE work.

Approach

We approached the challenge of “mapping” the scholarly community through an iterative surveying approach between 2016–2018. The survey was designed for the express purposes of mapping the landscape of URE work by asking participants to:

-

- characterize their own discipline, role, and policy/practice sector,

-

- identify key scholars whose work has influenced their own perspectives and work,

-

- identify key references which have influenced their own URE work.

This yielded descriptive information about work happening in this space, as well as network data in which individuals and disciplines are linked via referential relationships.

Sample

Our sample consists of a community of scholars and practitioners affiliated with URE efforts, particularly those tied to the work of the William T. Grant (US) and Nuffield foundations (UK). As the authors of this report were linked through the William T. Grant Foundation’s Using Research Evidence initiative, we began by approaching those invited to their annual gathering in 2016 (n = 102). We recognize that, as an invited event, limits the initial sample in many ways. It over-represents the United States, as well as scholars funded by the foundation, which has a substantive focus on child education and welfare. Nonetheless, the event has grown from grantees to broader set of U.S. scholars, as well as international scholars, policy leaders, and practitioners across policy areas. Moreover, as far as we are aware, it is the only academic conference to focus specifically on the study of the use of research evidence, and is therefore a reasonable seed sample to begin with.

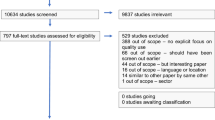

In order to grow from this initial set of participants, we used a snowball approach, using responses from the prompt to identify up to five individuals they would consult, either in person or through their work, about use of research evidence. We then invited those individuals to participate, achieving a total of 80 respondents of the 219 ultimately invited (39 from the 102 original sample, and 41 from the additional 117 identified through the snowball method). This approach helped us to better represent the URE landscape, as well as understand the potential scope of networks within a larger community; although, as indicated above, we as yet have only a partial understanding of who is working on this, and how.

Our sampling concluded in 2018 with the inaugural Transforming Evidence meeting, an international convening of scholars, practitioners and funders hosted by the Nuffield Foundation in London. This meeting had an explicit remit to cross disciplinary and sectoral boundaries. Participants were invited as leading scholars, funders, or practitioners with profile within, and knowledge of their communities. The survey was administered for the final time to this set (n = 54), and the data combined for a total of 134 participants.

Analysis

We rely on three analytical approaches: descriptive statistics, social network analysis and bibliometric analysis. First, we employ a basic descriptive approach to consider the composition of the URE community and the varied ways in which scholars and practitioners identify with URE work. More specifically, we describe the community in terms of discipline and policy area, present ways in which work is funded, and examine the keywords scholars use to describe their work and the fields to which they contribute.

Second, we utilize social network analysis to preliminarily explore the interpersonal links within this community. Participants were asked to identify up to five names of individuals who were either leading scholars who influenced their own work and perspectives on evidence production and use, or were advocates for better use of evidence, or better study of evidence. These individuals were characterized either through their survey response or by the researchers based on their publicly available biographies, and then added to the network. If multiple respondents nominated the same individual, they all have ties to that person. The characteristics of respondents and nominees were collated and used to analyze the network in terms of disciplines.

To explore the resulting network, we use UCINet to generate basic descriptors of network cohesiveness-density (the proportion of ties reported of all possible ties among respondents) and fragmentation (proportion of pairs of respondents that are “unreachable” through existing ties within the network). However, our approach to data collection—both limiting respondents to five nominations, as well as the high level of missingness resulting from response rates—creates limitations for the use of these metrics, which, particularly the whole-network measures, are sensitive to incomplete data.

Because of these limitations, we additionally consider homophily, an indicator of the extent to which an individual tends to associate with others like them. In our case, we explore homophily of disciplines, examining the extent to which nominated individuals are within one’s own disciplinary space or not. These measures are not sensitive to missingness in the data as they are calculated from individuals’ own responses. We generated homophily statistics by creating egonetworks in UCINet for each respondent, calculating the percentage of same-discipline scholars in their network.

Finally, we asked all respondents to nominate up to five key references of scholarly works which had influenced their own perspective about and work on how evidence was produced and used. These were compiled and descriptively analyzed to identify patterns and trends in influential works in the field. These data complement the social network analysis and provide further insight into the extent to which the community is drawing on a shared knowledge base or a more fragmented one.

Key findings

What did we learn about the composition and nature of the scholarly community we examined?

Our data revealed that the URE scholarly community spans the boundaries of research, policy, and practice, and represents diverse disciplines and fields of work, inhabiting a truly multidisciplinary space. However, its ability to boundary span is at once a strength to the community and a challenge.

A cross-sector community

Most of the respondents worked in an academic setting: more than two-thirds in an academic department of university-based research center. Others were embedded in independent research centres or think tanks (11%), philanthropic organizations or research funders (11%), non-profit or NGOs (5%), and government agencies (2%), with three individuals not identifying with any of these categories.

That the community crosses multiple sectors seemed to be reflected in the respondents’ field of practice as well (Fig. 1). Most respondents focused their work on education (26%) or health sciences (22%) as field of policy or practice. Other fields with which members identify include criminal justice (10%), 8% in public administration (8%), innovation and science policy (8%), human services (including social work and child welfare, 8%), international development (3%), communications (3%) and social policy (3%), and conservation and environmental science (3%). A few identified with other fields, such as housing, community psychology, sport, urban policy, and evaluation. In addition, a notable proportion of the actors described to be working beyond one specific field alone. One scholar remarked: “I work across issues, on topics identified by policymakers themselves. I would also describe myself as studying research utilization in policymaking, evidence-based policymaking, and research-based policymaking”. In this sense, both the community itself, and its members are often working across policy spaces.

Further evidence is found in grant support (Fig. 2); we asked respondents to report: What funding sources have supported your work, if any? Respondents indicated funded by a range of sources, from private philanthropies to government agencies, demonstrating the scope and scale of commitment across the globe. We note the multiple dimensions of diversity in this list, including level of system (local, state/regional, national, and international), governance (public, private, and corporate), and the range of policy areas in which funding is available. The range is promising, revealing breadth of support across multiple sectors. However, the data also reveal the range may also pose challenges for coordinating work across sectors and geographical boundaries, for scholars’ ability to access financial support across a highly distributed set of institutions, and for moving beyond a diffuse set of small research projects to a set of sustained work for the field.

A multidisciplinary space

Evident in Fig. 3, we find most members of this scholarly community identified with traditional social science disciplines, including sociology (27%), political science (20%), organizational studies (14%), psychology (12%), and economics (2%). Others identified with more interdisciplinary traditions, such as science and technology studies (8%), communication (3%), evaluation (1%), and social policy (1%). Although rare, other traditions such as law, learning sciences, and race studies or were mentioned as well. Surprisingly, three disciplines with a relatively rich history of exploring research use (i.e., economics, science and technology studies (STS), and communications) are among least commonly mentioned as the respondents’ disciplinary traditions, which we interpret not as an absence of work in this area but rather a sign of exclusiveness in our sample, potentially within our community, given the larger universe of scholars, funders and practitioners we know to be active.

Even within the URE community, multiple key topics were described by respondents. 90% of respondents selected one or more of the following categories: policy studies (21%), knowledge utilization (18%), evidence-based or evidence-informed decision-making, policy, practice (17%), research impact (15%), implementation science (11%), and knowledge mobilization (9%). However, we did offer an ‘other’ category, which yielded an additional 26 terms to describe the field to which members contribute, most of which are mentioned but once. These include literatures more closely tied to disciplines and policy or practice areas, such as politics of evidence or communication and information studies, as well as more terms with smaller niches within the URE space, such as sociology of knowledge, research on research use, and evaluation science. Even more diffuse than the set of other literatures were the range of key words respondents used to describe themselves and their work—263 different terms to be exact (see Fig. 4). This necessarily reflects diverse policy areas, disciplinary traditions, and methodological approaches, but may also inhibit the ability to locate and access prior knowledge about URE work, which perpetuates silos and slows the advancement of the field.

Even though they sound similar, and many people described themselves as contributing to one or more of these areas, each category in fact describes its own research tradition, with terms, concepts, tools, and an intellectual tradition of its own, a defining feature of multidisciplinarity (Wickson et al., 2006). Thus, for example, although common in the UK, none of the US respondents used the terms ‘knowledge mobilisation’ or ‘research impact’. Any cohesiveness observed in the scholarship is despite these differences, and reflects the efforts of scholarship to make their research relevant to different traditions.

How are these characteristics of the community reflected in interpersonal and bibliometric analyses?

The diversity of the URE community is further reflected in our network analysis, in which we asked respondents:

-

1.

Scholars contributing to the academic field of research use, or

-

2.

Scholars and others advocating for or ‘doing’ research use

Network analysis (Fig. 5) suggests that while there is a large cluster of reasonably high density indicating some coherence in terms of community, there are also several smaller, largely disconnected clusters, which broadly correspond to the policy sciences/social work/public administration disciplines. Standard network statistics confirm that the community displayed in Fig. 5 is lacks cohesion, with low density (.003) and high fragmentation (.990). Further, both visually and statistically we found evidence of disciplinary siloing. For example, we see dense clusters of education (bottom, red), health sciences (pink, at right), and organizational studies, blue, at top center). Homophily analysis, however, suggest a more promising foundation for boundary spanning among disciplines. Statistics reveal that the average respondent’s network is comprised of both internal and external scholars, with about half of scholars coming from outside their own discipline (mean proportion = .50), though the range is from 0 to 1.

We acknowledge that this analysis is incomplete, as we by no means captured the entire URE community, and that our responses are biased by the sample with which we started (the William T. Grant Foundation URE meeting) and missing data. Further, constraining respondents to five nominations, while advantageous for data collection, may limit identification of weak ties (such as those between disciplines). Together these likely contribute to low density and high frequency, and so we consider these findings exploratory. Nonetheless, we find the results a useful starting point for assessing the cohesiveness of the URE field, particularly given that the two meetings which provided the seed samples for these networks explicitly aimed to gather the interdisciplinary global—if small—community together. Our interpretation of these results is that, overall, we see less interdisciplinary connection than we believe is optimal for advancing the field, and that work is required to enable these relationships to develop.

The potential disconnect among scholarship in URE is also confirmed in our analysis of scholarly references individuals listed as particularly influential in their work. Respondents nominated 185 references across a range of disciplines, policy issues, and publication formats spanning more than five decades. Sixty two separate books were referenced, as well as 21 reports or conference proceedings. Articles from 57 journals were identified, overwhelmingly from health and education fields. The most referenced journal was Implementation Science, with five publications, and the most nominated author was Carol Weiss, with eight distinct publications.

Further, of the 182 nominated references (Appendix A), 140 were nominated by only 1 person; i.e., only 45 were nominated by two or more of our interdisciplinary community of 219 respondents. The oldest was Milgram’s Small World’s experiment from 1967. The first burst of publications is around 1977–1985, which seems to herald an explosion of research into education, political science, and network theory. The first paper explicitly about evidence is “Weiss (1977) Research for policy’s sake: The enlightenment function of social research. Policy Analysis, 3, 531–545” and the first STS paper in 1979 (Latour and Woolgar, 1979). From the 1990s onwards we see an expansion of publications about criminal justice, healthcare, and development, with continuing strong representation from education and political science.

This is evidently a small collection, but indicative of a few key features. Firstly, that there are very few papers which are cited by people from different fields—only four were nominated more than four times, and all were from politics and public policy, public sector management and evaluation. Thus, we can hypothesize that while many disciplinary conversations are being had about evidence production and use, few disciplines are managing to draw on interdisciplinary canonical literature for URE. Further, there is no evidence of these empirical studies building on core works in their own or other disciplines.

Secondly, as so few papers were nominated more than once, this indicates a highly fragmented network. This fragmentation relative to the social network suggests that individual scholars may have connections among one another but that those relationships have not yet yielded more interconnected scholarship.

Discussion

The significance and relevance of URE across disciplines and policy and practice domains has long been recognized, and has enjoyed a resurgence in the last decades as described earlier. At the same time, URE community may not reflect more traditional conceptualizations of a “field”—journals, professional associations, conferences, and employment prospects (i.e., do universities hire scholars in URE?). This raises concerns about the ability of the community to grow in size and influence, as well as its ability to accumulate and advance knowledge about the use of research in policy and practice.

So what can we learn from this preliminary work about the URE community? We began with an interest in mapping URE networks to understand of the coherence and inclusiveness of a particular scholarly community but also to point to what is needed to extend the boundaries of the community in order to advance and promote its collective work. Our findings, although only a partial view of the space, highlight the potential strengths of the URE scholarly community—its multidisciplinarity, boundary-spanning, the emerging conceptual coherence of its scholarship, and its broad base of support from funders. At the same time, we observe persistent challenges that may constrain the accumulation of knowledge and formal recognition of the work as a field, namely the fragmented, often siloed nature of URE networks, and both policy-specific and discipline-specific language and literatures.

How can increase connectedness of the community?

Without wanting to over-interpret our findings, network analysis provides an indication that the URE community at present is somewhat fractured, and that more could be done to strengthen links between disciplinary silos. More traditional fields of study enjoy professional associations, conferences, and associated journals that foster sharing of ideas, opportunities for collaboration, and a shared space to set research and policy agendas. The opportunities afforded by these structures make people and knowledge more accessible, which may help the community become more influential, recognizable, and cohesive. They also promote the accumulation of knowledge across disciplines and policy sectors, which will prevent researchers mistakenly thinking they are the first to foray into this terrain.

It is perhaps not surprising that this fragmentation has continued despite the rhetorical value placed on improved evidence use by all parties. Most conferences and workshops (even where professing the opposite) are heavily skewed towards single disciplines or sectors. It is very challenging for researchers to work across disciplinary boundaries; to learn about and use research from other fields; to overcome limited and intermittent funding and limited career-building opportunities. Facing up to these challenges feels a vital step if we are going to improve the quality of the research in this area.

Intentional efforts to bring together this diverse community, such as the URE meeting of the William T. Grant Foundation and the Transforming URE meeting funded by the Nuffield Foundation, which motivated this work, are starting points for improving the connectedness of the field. Further, journals such as Evidence and Policy which are inclusive of multiple disciplines and policy sectors promote sharing of work across boundaries. However, these may not be sufficient to achieve the level of connectedness needed to truly advance the work of the community. We call for more opportunities to listen, share, and build knowledge with each other. For example, funders can prioritize interdisciplinary and/or cross-sector programs of research that promote sustained connections across the community. Associations with special interest groups related to URE can create mechanisms for communication and sharing of research. Further strategies might be found by learning from and leveraging the ties of those boundary spanning scholars we find in our network and bibliometric analyses. In any of these strategies, time to meet and listen to each other, to learn the stories of work in progress is an essential ingredient if we are really going to do new and interesting work in this area.

How can we make the field more inclusive?

As we think about the connectedness within the boundary of the community, we must also pay attention to those outside and at the margins. In our silos we miss the opportunity to hear critical voices that challenge the dominant discourse in this space. For example, Althaus (2020) points out the contribution of indigenous knowledge could make to public policy, specifically pointing to both the products of policy and how evidence can inform policy (Boaz et al., 2019b). Work by Naquin et al. (2008) showcase a model for the development and use of evidence that is culturally congruent with indigenous peoples and validated by research and funding communities. Yet this work remains marginalized in URE.

Further, we noted earlier that the community was heavily academic. In contrast, we note that the work of knowledge mobilization—and, accordingly, important knowledge about research use and production—happens largely in the policy and practice communities. As URE focuses largely on improving ties between research and policy or practice, it follows that the community itself should be inclusive of those on-the-ground, creating richer opportunities to learn with and from policy and practice, as well as improve the flow of ideas between communities. An example of where we see these communities coming together is through co-production (e.g., Durose et al., 2011; Holmes et al., 2016) and research-practice partnerships (Penuel et al., 2015). Both approaches to the use of research center the user and promote engagement across research, practice, and policy boundaries. As these approaches secure greater support from the research institutions and funding agencies, the URE community has the opportunity to become more inclusive of a broader range of stakeholders.

How can we advance this work in policy and practice?

In addition to the need to be more connected and inclusive, a potential implication of our findings is that the URE community—and the broader study of the production and use of research—is not effective in promoting the evidence it generates. In other words, increased calls for evidence-based policy generate investments in capacity for the use of research: investments which can and should be informed by the decades of literature. However, the fragmented nature of the URE community, evident particularly in our citation network, make it difficult to point to a coherent set of best practices to inform capacity-building initiatives. Further, there is a real risk that without greater coherence, our collective work will result in repetitive or competing findings rather than robust, cumulative knowledge-based approaches needed to move the needle on deeply entrenched processes in both research production and policymaking communities. This community, perhaps more than any other, needs to base its work on the best evidence of what works (in supporting the use of evidence) for whom and in what circumstances. This is an area in which there is scope for the community to work more closely with research funders as key stakeholders.

How can we sustain the community in the long term?

URE has an extensive history in research, policy, and practice, yet has come in and out of focus over time. Our findings suggest URE has difficulty moving beyond projects that incrementally advance the knowledge base, evidenced in part by the high fragmentation in the bibliometric results. While efforts to increase the connectedness of the field may facilitate communication and contribute to a clearer body of knowledge on which to build, a more coordinated approach to supporting the work is needed. Noted above, one downside to a distributed set of funders is that there is no clear way of making sure the funding is more sustained and consistent so that we do not get pockets of excellence emerging only to disappear and risk that learning to be lost.

For funders, this means recognizing URE as a cross-cutting area where support for interdisciplinary and collaborative work is needed. Although all funders are interested in maximizing the value of their investments, only a few take the study of evidence production and use seriously. In turn, this means that careers in this area cannot be built, so all who want to work on this problem have to do so as an ‘add-on’ or one-off to their ‘real’ research. Significant bodies of empirical and theoretical research are not easy to generate, and so where funders do invest, they often do so without an informed knowledge of the real knowledge gaps, leading to waste repetition and lack of progress. Those who choose to conduct relevant research face challenges in continuing to pursue research in this area due to lack of funding opportunities. Finally, it is time to recognize that there is a broader audience for this work, and to make research about evidence production and use (whatever we call it) more broadly available, and to recognize this as a distinct area of study which funders can support together.

Conclusions

In summary, then, we argue that the community of scholars, practitioners, policymakers and funders who share interests in how evidence is made and used is poorly connected. This means that when new research is done about evidence production (under the umbrellas of ‘meta-science’, ‘research on research’, ‘use of evidence’ or some other term), it is all too easy to ignore the decades of research on this topic which has already been done. This leads to wasted research, repetitive investigations leading to the same conclusion, and, unfortunately, an over-claiming about what new research in this area can deliver. There is, in our view, no silver bullet and no easy answer to how evidence can be made and used more effectively; there is no substitute for human interaction and learning, and for joint thinking. But this takes time, investment in people and careers, and a shared endeavor founded on intellectual humility and generosity.

To deliver this, then, will take:

-

- time and opportunity to identify and map all those working on these related questions,

-

- engagement with these different communities to understand their research traditions, terminology and contributions to this interdisciplinary conversation,

-

- opportunity to spot and broker potential links between parts of this community who would benefit from better interdisciplinary collaboration,

-

- leadership, investment, and opportunity to share our learning with one another.

Only then can we truly begin to do new and exciting research with each other.

We leave these questions open for discussion, and call for further assessment and dialogue on the promise of URE. The last 15 years have brought significant momentum in the scholarship and practice of URE, and with continued engagement among government agencies, foundations, research institutions, non-profits, and others, we can collectively advance, and transform, the use of research evidence.

We urgently need a better understanding of who is working to improve use of evidence, who is studying the production and use of evidence, and who is supporting this work. Until we know how different members of our community frame and describe the set of shared problems we are engaged with, we will struggle to identify meaningful gaps or to learn from one another. The approach we have taken in this paper offers a way to begin (a) mapping and (b) engaging with the conversations ongoing in different parts of this wider universe. To advance, this demands more sustained, coordinated efforts and support from funders, academic associations and conferences, journals, and more. We offer some ideas and questions to both members of the URE community and those sectors best positioned to support the field moving forward.

This work has offered us an indication of the size and scope of this space, and a possible approach to begin identifying those connections which need to be built. In our view, this will take significant resources, in order to understand the different research traditions, the contributions they have made to this space, the conversations which need to be facilitated between different communities, and the ways to build those links. We do not underestimate this task; and this paper represents a small step forward. Rather, we have tried to illustrate the possible scale of the task, an approach which we think may help, and to imagine the potential benefits to us all which may be realized.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during this study are not publicly available due to the potential identifiability of survey participants.

Notes

Here we refer to research evidence, and subsequently evidence, as defined by Boaz et al. (2019b) as “any systematic and transparent gathering and analysis of empirical data” (p5). We recognize that definitions vary from field to field and that such evidence is but one form valued in policy and practice.

References

Acworth EB (2008) University–industry engagement: the formation of the Knowledge Integration Community (KIC) model at the Cambridge-MIT Institute. Res Policy 37:1241–1254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2008.04.022

Althaus C (2020) Different paradigms of evidence and knowledge: recognising, honouring, and celebrating indigenous ways of knowing and being. Aust J Public Adm. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12400

Backer TE (1991) Knowledge utilization: the third wave. Knowledge 12(3):225–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/107554709101200303

Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H et al. (2015) An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol 3(1):32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9

Beal GM, Dissanayake W, Konoshima S (1986) Knowledge generation, exchange and utilization. Westview Press, Boulder

Boaz A, Davies H, Fraser A, Nutley S (2019a) What works now? Evidence-informed policy and practice. Policy Press, Bristol

Boaz A, Davies H, Fraser A, Nutley S (2019) What works now? An introduction. In: Boaz A, Davies H, Fraser A, Nutley S (eds) What works now? Evidence-informed policy and practice. Policy Press, Bristol, UK, p. 1–16

Bransford JD, Stipek DJ, Vye NJ et al. (2009) The role of research in educational improvement. Harvard Education Press, Cambridge

Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking (2017) The promise of evidence-based policymaking: report of the Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking. Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking, Washington, DC

Duncan S, Oliver S (2019) The humanity of engagement at the core of developing and sharing knowledge. Res All 3(2):125–128. https://doi.org/10.18546/RFA.03.2.01

Durose C, Beebeejaun Y, Rees J, Richardson J, Richardson L (2011) Towards co-production in research with communities. AHRC Connected Communities Programme Scoping Studies. https://ahrc.ukri.org/documents/project-reports-and-reviews/connected-communities/towards-co-production-in-research-with-communities/

Feyerabend P (1961) Metascience. Philos Rev 70(3):396–405. https://doi.org/10.2307/2183383

Finnigan KS Daly AJ (eds) (2014) Using research evidence in education: from the schoolhouse door to Capitol Hill, Vol 2. Springer Science and Business Media, New York

French RD (2018) Lessons from the evidence on evidence‐based policy. Can Pub Adm 61(3):425–442

Gitomer DH, Crouse K (2019) Studying the use of research evidence: a review of methods. William T. Grant Foundation, New York

Haskins R (2018) Evidence-based policy: the movement, the goals, the issues, the promise. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 678(1):8–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716218770642

Holliman R (2019) Fairness in knowing: how should we engage with the sciences? The Open University, Milton Keynes

Holmes B, Best A, Davies H, Hunter DJ, Kelly M, Marshall M, Rycroft-Malone J (2016) Mobilising knowledge in complex health systems: a call to action. Evidence Policy 13(3):539–60

Ioannidis JPA, Fanelli D, Dunne DD, Goodman SN (2015) Meta-research: evaluation and improvement of research methods and practices. PLoS Biol 13(10):e1002264. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002264

Jasanoff S (ed) (2004) States of knowledge: the co-production of science and the social order. Routledge, London

Latour B, Woolgar S (1979) Laboratory life: the social construction of scientific facts. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills

Lievrouw LA (1989) The invisible college reconsidered: Bibliometrics and the development of scientific communication theory. Commun Res 16(5):615–28

Lawlor J, Mills K, Neal Z et al. (2019) Approaches to measuring use of research evidence in K–12 settings: a systematic review. Educ Res Rev 27:218–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.04.002

Martin S (2010) Co-production of social research: strategies for engaged scholarship. Public Money Manag 30(4):211–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2010.492180

Mukerji C (2001) Science, social organization of. In: Smelser NJ, Baltes PB (eds) International encyclopedia of social and behavioral sciences. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 13687–13691

Munafò MR, Nosek BA, Bishop DVM et al. (2017) A manifesto for reproducible science. Nat Hum Beh 1(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1108/17479886200800006

Naquin V, Manson S, Curie C et al. (2008) Indigenous evidence‐based effective practice model: indigenous leadership in action. Int J Leadersh Public Serv 4(1):14–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/17479886200800006

Nightingale P (1998) A cognitive model of innovation. Res Policy 27(7):689–709. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(98)00078-X

Nolan M, Hanson E, Grant G et al. (2007) Introduction: what counts as knowledge, whose knowledge counts? Towards authentic participatory enquiry. In: Nolan M, Hanson E, Grant G, Keady J (eds) User participation in health and social care research. Open University Press, Berkshire, UK, p. 1–13

Nyanchoka L, Tudur-Smith C, Iversen V et al. (2019) A scoping review describes methods used to identify, prioritize and display gaps in health research. J Clin Epidemiol 109:99–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.01.005

Oliver K, Boaz A (2019) Transforming evidence for policy and practice: creating space for new conversations. Pal Commun 5:60. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0266-1

Parkhurst J (2017) The politics of evidence: from evidence-based policy to the good governance of evidence. Routledge, London

Pedersen DB, Grønvad JF, Hvidtfeldt R (2020) Methods for mapping the impact of social sciences and humanities—a literature review. Res Eval 29(1):4–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvz033

Penuel WR, Allen AR, Coburn CE, Farrell C (2015) Conceptualizing research–practice partnerships as joint work at boundaries. J Educ Students Placed Risk 20(1–2):182–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2014.988334

Rogers E (1995) Diffusion of innovations, 4th edn. The Free Press, New York

Smith KE, Pearson M, Allen W et al. (2019) Building and diversifying our interdisciplinary giants: moving scholarship on evidence and policy forward. Evid Policy 15(4):455–460. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426419X15705227786110

Thornicroft G, Rose D, Huxley P et al. (2002) What are the research priorities of mental health service users? J Ment Health 11(1):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/096382301200041416

Tseng V (2012) The uses of research in policy and practice and commentaries. Soc Policy Rep 26(2):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2379-3988.2012.tb00071.x

Tseng V, Coburn C (2019) Using evidence in the US. In: Boaz A, Davis H, Fraser A, Nutley S (eds) What works now? Evidence-informed policy and practice.Policy Press, Bristol, pp 351–368

Van der Meulen B (1998) Science policies as principal–agent games: institutionalization and path dependency in the relation between government and science. Res Policy 27(4):397–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(98)00049-3

Waltman L, Rafols I, van Eck NJ, Yegros A (2019) Supporting priority setting in science using research funding landscapes. Research on Research Institute, London

Watermeyer R (2014) Issues in the articulation of ‘impact’: the responses of UK academics to ‘impact’ as a new measure of research assessment. Stud High Ed 39(2):359–377

Weiss CH (1977) Research for policy’s sake: the enlightenment function of social research. Policy Anal 3(4):531–545

Weiss CH (1979) The many meanings of research utilization. Public Adm Rev 39(5):426–431. https://doi.org/10.2307/3109916

Wickson F, Carew AL, Russell AW (2006) Transdisciplinary research: characteristics, quandaries and quality. Futures 38(9):1046–1059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2006.02.011

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the William T. Grant Foundation and the Nuffield Foundation for support of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Farley-Ripple, E.N., Oliver, K. & Boaz, A. Mapping the community: use of research evidence in policy and practice. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7, 83 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00571-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00571-2