Abstract

The Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011 had a serious psychological impact not only on residents, but also on public servants who worked for residents in prefectures and municipalities. Although public servants worked in highly stressful situations, disaster-related stress among them has not been studied, as has been the case for residents. We examine the stress trajectory of Ishinomaki public servants in Miyagi prefecture (N = 573; 317 men, 256 women), which was directly affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake, and analyse the effects of risk factors that included poor workplace communication, insufficient rest, having dead or missing family members, and living in a shelter. Six surveys were conducted (baseline approximately three months after the earthquake, and follow-up in approximately six-month intervals over a four-year period) using the Japanese version of the Kessler six-item Psychological Distress Scale. The analysis was conducted using five models, which included one for each risk factor and all four risk factors. Latent growth curve analysis indicated that stress response follows a cubic trajectory over four years. Psychological distress sharply reduced from 2011 to 2012 before stabilising and then slowly declining from 2014 to 2015. In the results of the analysis for each model, all risk factors affected stress response in the baseline. Individuals with poor levels of workplace communication experienced higher stress than those who had good levels of workplace communication. Our findings show that public servants’ stress responses decrease with time, regardless of whether or not there are risk factors involved. These results suggest that workplace communication in daily life can prevent the deterioration of mental health since risk factors affect the baseline of stress response.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

On March 11, 2011, at 14:46, a massive undersea earthquake, measuring 9.0 on the Richter scale, caused a tsunami that devastated the shoreline of east Japan from Tohoku (especially, Iwate Prefecture, Miyagi Prefecture, and Fukushima Prefecture) to the Kanto region. In total, 15,894 people died, while 2546 people were reported missing (Japan National Police Agency, 2017) and 77,436 people were living as internally displaced persons as of 2017 (Japan Reconstruction Agency, 2017). Ishinomaki city was one of the most seriously damaged areas in Miyagi Prefecture. Ishinomaki city had a population of 160,826 before the disaster. After the disaster, 3553 people had died, 425 were missing, and 53,038 houses were completely or partially destroyed (Miyagi Prefecture Government, 2017).

Previous research related to the Great East Japan Earthquake disaster targeted residents (Yabe et al., 2014; Yokoyama et al., 2014), children (Usami et al., 2012), pregnant women (Watanabe et al., 2016), and psychiatric patients (Matsumoto et al., 2014; Wada et al., 2013). This disaster affected the mental health of not only residents, but also public servants. Public servants are involved in affairs concerning life of residents in prefectures and municipalities. While public servants in prefectures conduct wide-area local government affairs encompassing municipalities, those in municipalities conduct basic local government affairs closely connected to residents’ daily lives (Council of Local Authorities for International Relations, 2010). Even though they were victims of the disaster, they had to support residents during the restoration of towns and cities. The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (2007) reported that public servants are one of the potentially supportive social resources for community recovery. However, Japanese residents want public servants to respond to their demand and recover the fundamentals of their lives immediately. If their demand is not fulfilled, some residents criticise the public servants. In addition, unlike temporal rescue workers who work in damaged areas for a defined period of time, public servants must respond to needs for a long period. They face victim-related and job-related stressors during this long period. Therefore, it is necessary to identify the long-term changes in the stress of public servants.

A recent systematic review of occupational groups affected by disaster (Brooks et al., 2017) suggested that pre-disaster experiences, job satisfaction, traumatic exposure, perception of safety, harm to self/close others, social support, and post-disaster impact on life were important to all workers. In terms of public servants, government staff who were in close proximity to disasters including terror attacks showed greater prevalence of low mental health, post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, depression, and alcohol abuse (Grieger et al., 2004, 2005; Hansen et al., 2013; Jordan et al., 2004) than those who were not. In Japan, public servants are often criticised by the public in everyday circumstances because many Japanese people believe that public servants are stable in various aspects, such as employment, salary, and social security. In terms of social factors in times of disaster, workers received a lack of positive acknowledgement from others, which was associated with low mental health (Brooks et al., 2017). Therefore, Japanese public servants in disaster areas would be more susceptible to low mental health than would be those with other occupations, because of proximity to the disaster and a lack of social acknowledgement.

In addition, Suzuki et al. (2014) revealed an association between four possible risk factors (i.e., poor workplace communication, insufficient rest, having dead or missing family members, and living in a shelter) and mental distress among public servants in the Miyagi prefectural government after the Great East Japan Earthquake. In other words, regardless of whether they were directly affected by the disaster, public servants may have experienced mental health problems. Of note, the long-term mental health trajectory of these public servants has not been addressed.

In this study, we focused on public servants in Ishinomaki city, a coastal city and the second most populated city in Miyagi Prefecture, and examined the previously noted four risk factors that may affect their mental health recovery process. Suzuki et al. (2014) did not reveal the long-term stress trajectory or investigate how the four risk factors affected public servants’ stress trajectory. The first goal was to test whether their stress trajectory could be captured by linear or curvilinear growth models. The secondary goal was to analyse these four factors that could affect the overall level and shape of the stress trajectory: poor workplace communication, insufficient rest, having dead or missing family members, and living in a shelter.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The current study was a secondary data analysis of a health survey conducted on local government employees of Ishinomaki city, Miyagi Prefecture. The survey began in June 2011, when the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred, and ended in July 2015. We used data from six periods in this research, which included demographic variables and psychological distress questionnaires with 1452 regular workers: Time 1, June 2011; Time 2, October 2011; Time 3, June 2012; Time 4, February 2013; Time 5, February 2014; and Time 6, July 2015. Their types of staff included: staff engaging in affairs related to the fundamentals of residents’ lives (e.g., residential taxes, family registers), staff engaging in the provision of infrastructure (e.g., water supply, garbage disposal), staff engaging in the welfare and health of residents (e.g., affairs of nursing insurance, nurses within the city-run hospital), and staff engaging in the establishment and management of various facilities (e.g., community hall, elementary and junior high schools).

We obtained permission for the use of secondary data from Ishinomaki city and the Ethics Review Committee of Tohoku University Graduate School of Education approved the study (No. 16-1-024).

Suzuki et al. (2014) had used a web-based survey to investigate the public servants in Miyagi Prefecture. This research targeted the public servants in Ishinomaki city. In Japan, prefectures and cities (municipalities) are mutually independent local government entities (Council of Local Authorities for International Relations, 2010). Therefore, participants in this research were different from Suzuki et al. (2014) participants.

Measures

Demographic variables

Demographic variables included sex, age, communication with co-workers (yes, regularly; yes, occasionally; or no, not at all), whether participants worked overtime exceeding 100 h (yes or no), whether they experienced living without a domicile (yes, I have, but not now; yes, I still live in an arranged situation; or no, not at all), and whether or not family members had been killed or were missing (yes or no). We considered exceeding 100 h of work as insufficient rest. This portion of the survey was used only once at Time 1. Workplace communication and responses to whether participants had experienced living without a domicile were categorised. For workplace communication, yes, regularly and yes, occasionally were categorised as ‘yes’. With regard to whether participants had experienced living without a domicile, yes, I have, but not now and yes, I still live in an arranged situation were categorised as ‘yes’. In this study, we did not report other items because we used them for other purposes (Wakashima et al., 2014).

Main outcome measurement

Psychological distress was measured with the Japanese version of the Kessler 6-item Psychological Distress Scale (K6) (Kessler et al., 2002; Kessler et al., 2003). The Japanese version of the K6 was recently developed using the standard back-translation method and it has been validated (Furukawa et al., 2008; Sakurai et al., 2011). The K6 consists of six questions with five possible responses (0–4) for each question: ‘none of the time’ (0 points), ‘a little of the time’ (1 point), ‘some of the time’ (2 points), ‘most of the time’ (3 points), and ‘all of the time’ (4 points). The participants were asked if they had the following symptoms during the past 30 days: feeling so sad that nothing could cheer you up, feeling nervous, feeling hopeless, feeling restless or fidgety, feeling that everything was an effort, or feeling worthless. Total scores ranged from 0 to 24. We used K-6 scores from Time 1 to Time 6.

Statistical analyses

We used latent growth curve models to describe the stress trajectory and to determine whether this trajectory differed by the abovementioned four factors. Latent growth modelling uses repeated measures of a single variable to estimate two latent factors—the initial intercept and the slope. In this study, the intercept indicates the stress response at the time of the first survey, while the slope indicates the change in the stress response.

We specified a linear slope by applying the slope factor loadings to 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 from Time 1 to Time 6, respectively. A quadratic slope was also added to the model with factor loadings of 0, 1, 4, 9, 16, and 25; similarly, cubic slope factor loadings of 0, 1, 8, 27, 64, and 125 were added to capture nonlinear trends. Maximum likelihood estimation was calculated for all latent growth curve models. Missing data were calculated using a process called full information maximum likelihood (FIML). FIML uses all available data for each person, estimating missing information from relationships among variables in the full sample. The analyses were conducted with Mplus 8.1 (Muthén and Muthén, 2017).

Results

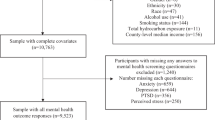

Figure 1 depicts the participants’ flow diagram. Table 1 shows participants’ basic characteristics. Overall, 147 participants (25.65%) had a Time 1 K6 score ≥ 10.

Our first goal was to estimate the trajectory of stress. We estimated a linear, quadratic, and cubic model. Table 2 provides the results of all latent growth analyses. For the linear model across all samples, the average initial level at Time 1(intercept) corresponded to an average rating of 6.26 (on a 0–24 scale) for K6 score and decreased by about 0.38 each time until Time 6. Therefore, we estimated it to be a quadratic and cubic model. The cubic model had the best fit to the data. Relative to the linear model, adding a quadratic term improved model fit (Δχ2(4) = 61.98, p < .001; ΔBIC = 62.69); relative to the quadratic model, adding a cubic term improved model fit (Δχ2(5) = 25.03, n.s.; ΔBIC = 1.59). Consequently, we estimated a cubic stress trajectory (Fig. 2).

Effects of covariates on growth parameters

Our second goal was to test for stress trajectory changes that were affected by the risk factors. We estimated five conditional growth curve models, one for each variable and one that examined all four variables simultaneously (Table 3).

With Model 1, we examined the effect of workplace communication on the trajectory. The results indicated that communication significantly influenced the intercept but not the slope of the curve. Participants with poor levels of communication showed higher stress levels than did effective communicators at all time points. With Model 2, we examined the effects of rest on the trajectory. The results indicated that rest significantly influenced the intercept, but not the slope of the curve. Participants getting insufficient rest showed higher stress levels than did those getting sufficient rest at all time points. With Model 3, we examined the effect of having dead or missing family members on the trajectory. The results indicated that having dead or missing family members significantly influenced the intercept and marginally influenced the linear, quadratic, and cubic slope. Participants with dead or missing family members showed higher stress levels than did those with no dead or missing family members at almost any time point. With Model 4, we examined the effect of the experience of living without a domicile on the trajectory. The results indicated that living without a domicile significantly influenced the intercept, but not the slope of the curve. Participants living without a domicile showed higher stress levels than did those who had a domicile at all time points. With Model 5, we examined the effect of all four variables simultaneously. The results were comparable to Models 1 through 4, except for the effect of having dead or missing family members on the intercept and the linear, quadratic, and cubic slopes. The intercept, which was significant in Model 3, revealed a nonsignificant trend in Model 5. Further, the linear, quadratic, and cubic slopes, which showed a nonsignificant trend in Model 3, became nonsignificant in Model 5. Therefore, although these four risk factors were associated with higher stress responses among participants, they were not associated with independent changes in the stress trajectory. Furthermore, the regression coefficients were not strongly changed when the risk factors were analysed simultaneously. Workplace communication, rest, having dead or missing family members, and living without a domicile are relatively independent risk factors for the stress trajectory. We observed that, among all risk factors, workplace communication affected the intercept the most.

Discussion

In this research, we investigated the stress levels of local government employees in Ishinomaki city after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Latent growth curve analyses suggested that the average trajectory of stress can be captured by a cubic curve. Psychological distress was sharply reduced at Time 3 from Time 1, but then became more stable (Time 4 and Time 5), and slowly declined from Time 5 to Time 6. Many studies revealed that the stress trajectory follows some distinct patterns (Bonanno and Diminich, 2013; Norris et al., 2009). However, it has been shown that the average value of distress will linearly decrease over time (Oe et al., 2016; Yabe et al., 2014). Our results reveal that distress not only decreased rapidly linearly, but also changed cubically.

We also found individual differences among the initial state of the stress trajectory. Workplace communication, insufficient rest, having dead or missing family members, and living in a shelter predominantly affected the initial stress state. It was revealed that risk factors affected the initial stress state but did not affect the subsequent long-term changes. In addition, from the result of four risk factors simultaneously, it was suggested that each of the risk variables are affected independently. Among the risk factors, workplace communication had been the most influential. Suzuki et al. (2014) revealed that poor workplace communication and insufficient rest, which were work-related stressors, impacted stress responses. Therefore, workplace communication was suggested to be an important variable in terms of capturing the mental health of public servants after the disaster. In this study, the reasons for workplace communication to affect stress responses the most can be outlined. First, employees were expected to work for a long time with co-workers; their relationships with coworkers were associated with psychological distress (Shigemi et al., 1997; Eguchi et al., 2012). When a disaster occurs, public servants must work long time for the benefit of the residents at the cost of all else. It is possible that because they work long time with co-workers, workplace communication might have a large influence on stress.

Second, the measurement of communication was different from Suzuki et al. (2014). Although Suzuki et al. (2014) measured the quality of the communication, this study measured the amount of communication. In addition, in the analysis, Suzuki et al. (2014) divided communication into ‘poor or reasonable’ and ‘good’; On the other hand, this study divided communication into ‘poor (not at all)’ and ‘reasonable (occasionally) or good (regularly)’. It was observed that ‘poor’ amount of communication was the problem. For this reason, it was concluded that workplace communication has a greater influence on stress response than the remaining factors. Moreover, workplace communication is the most controllable factor. Communication with colleagues in the workplace has positive effects on the mental health of workers. Sasaki et al. (2017) suggested that communication training, which is conducted in the workplace, could potentially improve the mental health of workers. It is important that all staff must acknowledge that workplace communication affects their mental health.

Limitations

The strength of this study is the longitudinal design and adequate samples used for analysis. This study reveals that the stress trajectory among local government employees in Ishinomaki city exhibited a cubic change from three months to four years after the Great East Japan Earthquake. However, this study has three limitations. First, although participants were informed that survey results would be classified and independent of any performance evaluation, they might have felt pressured to respond to the survey, and they may have provided false information about their working habits. Second, we did not investigate other risk factors such as health condition, income, alcohol consumption, and family psychiatric history. Harada et al. (2015) and Brooks et al. (2017) revealed many risk factors. In the future, we plan to address the relationship between these risk factors and the stress trajectory. Finally, this research failed to consider changes in circumstances of residents and workplace environment of public servants. For example, if residents have future prospect of living by receiving a domicile, the complaints against public officials will be reduced; this, in turn, may reduce the stress of public servants. In addition, changing from disaster-related departments to other departments will decrease individuals’ stress responses. It is possible that the stress trajectory among local government employees and changes in circumstances surrounding residents or servants might have been confounding.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, this study revealed that the stress trajectory among local government employees in Ishinomaki city exhibited a cubic change from three months to four years after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Further, four risk factors increased their base line stress response, but not the long-term stress trajectory. The amount of workplace communication especially affected stress responses. It was suggested that being aware of reasonable workplace communication could decrease stress after the disaster. People who experience less workplace communication will suffer the risk of high-stress response in the base line. Departments involved in the health of the staff must conveyed this to their staff through training. Moreover, public servants who recognise the importance of communication will be able to prevent mental health deterioration in areas where a large-scale disaster has not occurred. When a large-scale disaster occurs, we have to attend to not only the mental health of residents, but also that of the public servants who are responsible for the community’s recovery.

Data availability

This dataset was acquired by Tohoku University Graduate School of Education and Ishinomaki city for the psychological support of public servants in Ishinomaki city. Use of the dataset in the current study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tohoku University and Ishinomaki city; this dataset is not publicly available due to the personal information contained in the health survey data. Enquiries about the data should be directed to the corresponding author at Tohoku University Graduate School of Education, which commissioned the study.

References

Bonanno GA, Diminich ED (2013) Annual research review: positive adjustment to adversity–trajectories of minimal-impact resilience and emergent resilience. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Disciplines 54(4):378–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12021

Brooks SK, Dunn R, Amlot R, Rubin GJ, Greenberg N (2017) Social and occupational factors associated with psychological wellbeing among occupational groups affected by disaster: a systematic review. J Mental Health 26(4):373–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1294732

Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (2010) Local Government in Japan. http://www.clair.or.jp/j/forum/series/pdf/j05-e.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2019

Eguchi H, Tsuda Y, Tsukahara T, Washizuka S, Kawakami N, Nomiama T (2012) The effects of workplace occupational mental health and related activities on psychological distress among workers: a multilevel cross-sectional analysis. J Occupational Environ Med 54(8):939–947

Furukawa TA, Kawakami N, Saitoh M, Ono Y, Nakane Y, Nakamura Y, Tachimori H, Iwata N, Uda H, Nakane H, Watanabe M, Naganuma Y, Hata Y, Kobayashi M, Miyake Y, Takeshima T, Kikkawa T (2008) The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int J MethodsPsych Res 17(3):152–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.257

Grieger TA, Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ (2004) Posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and perceived safety 13 months after September 11. Psychiatric Services 55(9):1061–1063. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1061

Grieger TA, Waldrep DA, Lovasz MM, Ursano RJ (2005) Follow-up of Pentagon employees two years after the terrorist attack of September 11, 2001. Psychiatric Services 56(11):1374–1378. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.56.11.1374

Hansen M B, Nissen A and Heir T (2013) Proximity to terror and post-traumatic stress: a follow-up survey of governmental employees after the 2011 Oslo bombing attack. BMJ Open 3(7). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002692

Harada N, Shigemura J, Tanichi M, Kawaida K, Takahashi S, Yasukata F (2015) Mental health and psychological impacts from the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake Disaster: a systematic literature review. Disaster Military Med 1:17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40696-015-0008-x

Inter-Agency Standing Committee (2007) IASC guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. http://www.who.int/mental_health/emergencies/guidelines_iasc_mental_health_psychosocial_june_2007.pdf. Accessed 7 Nov 2018

Japan National Police Agency (2017) Damage and police responses to the northeast pacific earthquake. https://www.npa.go.jp/news/other/earthquake2011/pdf/higaijokyo.pdf. Accessed 7 Nov 2018

Japan Reconstruction Agency (2017) Number of evacuees nationwide. http://www.reconstruction.go.jp/topics/main-cat2/sub-cat2-1/20171227_hinansha.pdf. Accessed 7 Nov 2018

Jordan NN, Hoge CW, Tobler SK, Wells J, Dydek GJ, Egerton WE (2004) Mental health impact of 9/11 Pentagon attack: validation of a rapid assessment tool. Am J Preventive Med 26(4):284–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2004.01.005

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SL, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM (2002) Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 32(6):959–976

Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Normand SL, Manderscheid RW, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM (2003) Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch General Psychiatry 60(2):184–189

Matsumoto J, Kunii Y, Wada A, Mashiko H, Yabe H, Niwa S-i (2014) Mental disorders that exacerbated due to the Fukushima disaster, a complex radioactive contamination disaster. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 68(3):182–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12112

Miyagi Prefecture Government (2017) Information of earthquake damage and evacuation. http://www.pref.miyagi.jp/site/ej-earthquake/km-higaizyoukyou.html. Accessed 7 Nov 2018

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (2017) Mplus user’s guide: eighth edition. Author, Los Angeles

Norris FH, Tracy M, Galea S (2009) Looking for resilience: understanding the longitudinal trajectories of responses to stress. Social Science and Medicine 68(12):2190–2198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.043

Oe M, Maeda M, Nagai M, Yasumura S, Yabe H, Suzuki Y, Harigane M, Ohira T, Abe M (2016) Predictors of severe psychological distress trajectory after nuclear disaster: evidence from the Fukushima Health Management Survey. BMJ Open 6(10):e013400. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013400

Sakurai K, Nishi A, Kondo K, Yanagida K, Kawakami N (2011) Screening performance of K6/K10 and other screening instruments for mood and anxiety disorders in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 65(5):434–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02236.x

Sasaki N, Somemura H, Nakamura S, Yamamoto M, Isojima M, Shinmei I, Horikoshi M, Tanaka K (2017) Effects of brief communication skills training for workers based on the principles of cognitive behavioral therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Occupational Environ Med 59(1):61–66

Shigemi J, Mino Y, Tsuda T, Babazono A, Aoyama H (1997) The relationship between job stress and mental health at work. Industrial Health 35(1):29–35

Suzuki Y, Fukasawa M, Obara A, Kim Y (2014) Mental health distress and related factors among prefectural public servants seven months after the Great East Japan Earthquake. J Epidemiol 24(4):287–294. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20130138

Usami M, Iwadare Y, Kodaira M, Watanabe K, Aoki M, Katsumi C, Matsuda K, Makino K, Iijima S, Harada M, Tanaka H, Sasaki Y, Tanaka T, Ushijima H, Saito K (2012) Relationships between traumatic symptoms and environmental damage conditions among children 8 months after the 2011 Japan earthquake and tsunami. PloS ONE 7(11):e50721. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0050721

Wada A, Kunii Y, Matsumoto J, Itagaki S, Yabe H, Mashiko H, Niwa S (2013) Changes in the condition of psychiatric inpatients after the complex Fukushima disaster. Fukushima J Med Sci 59(1):39–42

Wakashima K, Kobayashi T, Kozuka T, Noguchi S, Ikuta M, Ambo H, Hasegawa K (2014) Longitudinal study of the stress responses of local government workers who have been impacted by a natural disaster. Int J Brief Ther Family Sci 4(2):69–94

Watanabe Z, Iwama N, Nishigori H, Nishigori T, Mizuno S, Sakurai K, Ishikuro M, Obara T, Tatsuta N, Nishijima I, Fujiwara I, Nakai K, Arima T, Takeda T, Sugawara J, Kuriyama S, Metoki H, Yaegashi N, Japan Environment and Children’s Study Group (2016) Psychological distress during pregnancy in Miyagi after the Great East Japan Earthquake: The Japan Environment and Children’s Study. J Affective Dis 190:341–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.024

Yabe H, Suzuki Y, Mashiko H, Nakayama Y, Hisata M, Niwa S-I, Yasumura S, Yamashita S, Kamiya K, Abe M, Mental Health Group of the Fukushima Health Management Survey (2014) Psychological distress after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Accident: Results of a Mental Health and Lifestyle Survey through the Fukushima Health Management Survey in Fy2011 and Fy2012. Fukushima J Med Sci 60(1):57–67. https://doi.org/10.5387/fms.2014-1

Yokoyama Y, Otsuka K, Kawakami N, Kobayashi S, Ogawa A, Tannno K, Onoda T, Yaegashi Y, Sakata K (2014) Mental health and related factors after the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami. PloS One 9(7):e102497. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102497

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Japanese Psychological Association’s ‘Research grants for reconstruction after disasters in 2016’ (KW).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KW and KA created the analysis plan, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. TH assisted in managing and analysing the data, statistical analysis, and providing critical comments on the methodological aspects of this study. SN supervised data collection for the entire study and participated in the interpretation of data and manuscript preparation. All of the authors discussed the data and results and critically revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

SN was an employee of Ishinomaki city as a clinical psychotherapist in 2012–2018. The remaning authors, KW, KA, and TH, declare no potential conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wakashima, K., Asai, K., Hiraizumi, T. et al. Trajectories of psychological stress among public servants after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Palgrave Commun 5, 37 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0244-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0244-7

This article is cited by

-

Executive function training for kindergarteners after the Great East Japan Earthquake: intervention effects

European Journal of Psychology of Education (2023)