Abstract

Evidence-based medicine is often described as the ‘template’ for evidence-based policymaking. EBM has evolved over the last 70 years, and now tends to be methodologically pluralistic, operates through specific structures to promote EBM, and is inclusive of a wide range of stakeholders. These strategies allow EBM practitioners to effectively draw on useful evidence, be transparent, and be inclusive; essentially, to share power. We identify three lessons EBP could learn from EBM. Firstly, to be more transparent about the processes and structures used to find and use evidence. Secondly, to consider how to balance evidence and other interests, and how to assemble the evidence jigsaw. Finally–and this is a lesson for EBM too–that understanding power is vital, and how it shapes how knowledge is produced and used. We suggest that advocates of evidence use, and commentators, should focus on thinking about how the type of problem faced by decision-makers should influence what evidence is produced, sought, and used.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This paper summarises how commentators and advocates have thought about evidence use in medicine and policy over the previous decades. We draw on existing literature to outline the debates about the main challenges to the evidence-use movements, and the strategies used by advocates to address these challenges. At times, the EBM and EBP movements have developed in parallel. Here, we compare the two movements, and identify lessons for each (and their critics) to learn. Finally, we summarise the main answered, and unanswered questions for researchers and practitioners of evidence-based decision-making.

Advocates of evidence-based policy (EBP) justifiably use evidence-based medicine (EBM) as a template for their activities. Health care is getting more effective, and the proliferation of clinical guidelines to cover more and more of the changing face of clinical practice indicates the success of this institutional approach (Montori, 2008). However, advocates of EBP sometimes use an idealised template of EBM, which indicates that all policy/practice decisions should be predominantly based on research evidence–even that only some forms of research are ‘valid’ enough to support decision-making–the randomised controlled trial (RCT) and systematic review. It is immediately obvious that this strict version simply wouldn’t work for EBP, as it dismisses too much useful information, and does not take account of people’s experiences and values. Critical commentators of EBP observe that ‘evidence-use’ is hard to diagnose and/or categorise (Parkhurst, 2017b; Smith 2013a), that focusing on evidence-use risks ignoring most of the machinery of decision-making (Oliver et al., 2014), and that what needs addressing by researchers and practitioners of evidence-based decision-making, is the ‘human factor’; power, actors, and context (Freudenberg and Tsui, 2013; Oliver et al., 2012; Wesselink et al., 2014).

This strict version is, however, a caricature. These days, most sensible people agree that there are good reasons for research evidence not overruling clinical experience by default: for example, the incompleteness of the evidence base or that clinical and lay experience should be recognised as vital components in the decision-making process, alongside a range of research types (Head, 2010). Instead, EBM is often presented as a practice where clinical decision-making is seen as a site of negotiation between different stakeholders, which include the (researcher-derived) evidence base, the clinician, the patient, and providers of care and services generally. Drawing on this perspective, we present three key lessons from these debates for practitioners of EBM and EBP.

First, that although the tools and practices developed by EBM (privileging RCTs and systematic reviews over practitioner discretion) and EBP (led by demands for evidence from political decision-makers) are different, there are opportunities for greater transparency about decision-making processes in policy. Second, we argue that EBM has developed ways to try and balance researcher, practitioner and public knowledge, without compromising methodological rigour or privileging some perspectives over others. Learning to assemble the evidence jigsaw is a complex process which goes beyond methodological pluralism, but requires research evidence to be applied in varying settings and balanced with other interests, potentially extending to the use of deliberative processes to develop consensus between different stakeholder values and priorities. Third, we argue that, whatever the epistemological stance of the practitioner, it is vital to understand the role of power in evidence-informed decision-making; that examining who exerts power and how, is fundamental to understanding how the practice of evidence-use occurs in both medicine and policy. Simply stating that power needs to be shared, or that deliberative processes should be used to reach consensus, does not helps us to describe, understand, or address underlying power imbalances in knowledge production, governance, or use.

The evolution of EBM: a roadmap for EBP?

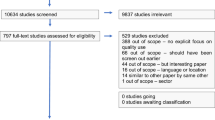

EBM has evolved significantly since its inception, with Cochrane’s answer to the injunctive of ‘do no harm’ (Cochrane, 1972). The opening salvo in the EBM movement was a call to use high-quality research evidence to select only effective interventions, ideally the RCT, which can provide evidence on effectiveness (whether an intervention has the desired outcome) and efficiency (whether this effect translates outside the research setting) of an intervention (Sibbald and Roland, 1998; Victora et al., 2004). RCTs reduce the role of chance in determining the outcome of experiments, and thus allow causal statements about the utility of interventions to be made with relative confidence. The 1990s saw the enshrinement of the RCT as the ‘gold standard’ form of evidence for EBM, often being portrayed as sitting atop the ‘hierarchy of evidence’ (Petticrew and Roberts, 2003) an heuristic to determine the credibility of research evidence in developing clinical guidelines and recommendations (see, e.g., GRADE (Ansari et al., 2009) and National institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) processes (NICE, 2004). Since these early days, limitations to the use of the RCT have been increasingly highlighted (Cartwright, 2007; Oliver et al., 2010; Victora et al., 2004), and in the last decade, the cultural hegemony of the RCT has come under attack as its ethical, pragmatic, political, and methodological limitations ––have become more apparent (Pearce et al., 2015).

To many advocates of EBP, including some politicians, it seemed self-evident that policy should be based on the best available evidence. Coming to prominence in the UK under the Blair Government, EBP assumed that with enough ‘sound evidence’ it was possible to move beyond the vagaries of party politics to reach “a firm high ground in the policy swamp” (Parsons, 2002, p 45). Drawing on the EBM template, the RCT was promoted as an optimal way to test and evaluate policy, with the UK civil service becoming increasingly supportive (Ettelt et al., 2015; Haynes et al., 2012; Oakley, 2000; Pearce and Raman, 2014; Pearce et al., 2015). In the US particularly, there is both a culture of policy innovation and experimentation, and, through the existence of the federal states, the means to conduct large-scale social experiments (Baron, 2009; Kalil, 2014).

However, it is now widely accepted in EBM that a range of evidence types should be used by clinicians and patients when making decisions, and that decision-making processes should be transparent and inclusive. This started in response to a need to cover more of the realities of patient experience and clinical practice (Greenhalgh and Hurwitz, 1999; Hammersley, 2007). We also now recognise the role of values and interpretation in understanding evidence, such that one piece of evidence may have multiple meanings (Pearce and Raman, 2014; Smith, 2014).

While these moves were significant in medicine, methodological pluralism has always been more acceptable in policy (Ingold and Monaghan, n.d.; Murphy and Fafard, 2012). Policy meanings affect the presentation, acceptance and framing of evidence and are vital to identifying levers for action (Grundmann and Stehr, 2012; Pearce et al., 2017).

Policymakers have always had to consider multiple framings of policy problems (Gold, 2009; Russell et al., 2008). In medicine, problem identification and diagnosis is relatively uncontested, whereas getting agreement on the nature of policy problems–let alone causes or solutions - is challenging (Cairney, 2012; Liverani et al., 2013; Weiss, 1979, 1991). The ‘hierarchy of evidence’ has less currency in an environment where policymakers must balance economic, financial, ideological and other perspectives on single issues (Lin, 2003). This is both a strength, in that policy has access to a diverse jigsaw of evidence, and a weakness in that the quality and reliability of such evidence is contested. It is not always clear what evidence is used, how it is identified, or who gets a voice in its production and interpretation (Dobrow et al., 2004; Oliver and de Vocht, 2017; Oliver and Lorenc, 2014).

Indeed, the narrow technocratic version of EBP which subscribes to the primacy of the RCT is now mainly used as a straw man (evidenced in, e.g., Freiberg and Carson, 2010; Marmot, 2004; Pawson, 2002). A significant amount of research and commentary has been conducted on multiple fronts; to guide policymakers to use research evidence more effectively in the UK (Cabinet Office, 1999; Campbell et al., 2007), Australia (Banks, 2009) and the USA (Laura and John Arnold Foundation, 2016); to investigate factors hindering evidence use (Innvaer et al., 2002; Oliver et al., 2013; Orton et al., 2011) and to develope interventions aiming to ‘upskill’ policymakers or help them to access the ‘best’ available evidence more efficiently (see, e.g., (Armstrong et al., 2013; Dobbins et al., 2009; Ward, 2017), or for a recent synthesis (Boaz et al., 2011)). Yet, there are still useful lessons that EBP could learn from EBM, and vice versa. Accepting that both EBM and EBP are more nuanced in practice, than in caricature, what lessons can they learn from one another?

Lesson one: be more transparent

EBP advocates could learn from EBP about how to develop clear and transparent processes and structures to inform decision-making. Institutions such as NICE provide epistemic governance and accountability regarding the creation and utilisation of knowledge–through, for example the clinical guidelines process, wherein groups of clinical and lay individuals assess systematic reviews of the literature and, together, produce sets of recommendations for clinical practice. Elsewhere, health research funders have supported collaborations between clinical and academic staff (such as the CLAHRCs, in the UK, and ZonMy in the Netherlands), in which research topics are co-developed, and/or findings implemented and evaluated.Footnote 1 Focusing more on research, the James Lind AllianceFootnote 2 is an example of the development and application of an explicit process to co-produce research agendas on health topics, drawing on the input of patients, carers, and practitioners to rank proposed research questions on a particular topic (Beresford, 2000; Jonathan Boote et al., 2010; Boote et al., 2002; Oliver, 2006; Stewart et al., 2011). However, there are few evaluations of whether these structures change either research or population-level outcomes.

Within policymaking, there has been similar investment in organisations institutionalise or formalise the process of identifying and codifying of evidence, and the translation of such evidence into policy recommendations. Again in the UK, the Blair/Brown Governments endorsed the “what works” principle, and funded What Works Centres, NICE and the Education Endowment Fund (Parsons, 2001). More recently, a variety of non-governmental bodies have entered the evidence ‘mix’, such as the Behavioural Insights Team, NESTA and IPPR in the UK, and Laura and John Arnold Foundation and Brookings in the US. While these are often well-resourced and sometimes influential, little is yet known about how, and how well, the knowledge produced by these new initiatives is taken up, or whether it leads to changes in population or patient outcomes (Head, 2017).

While many have recognised that the policy process is nuanced and negotiated rather than linear (Ettelt et al., 2015; Pearce et al., 2015; Sarewitz, 2009; Sarewitz et al., 2004), there remains strong support for the view that research evidence ought to inform more of policymaking (see, e.g., Armstrong et al., 2013; Dobbins et al., 2009; Ward, 2017). Yet, nothing in EBP compares to the transparency with which EBM finds and incorporates evidence into its decision-making processes.

Lesson two: balance inputs to assemble the evidence jigsaw

Next, it is important for decision-makers to think critically about what evidence is needed in the context of a particular decision; what research evidence, whose voices, which interests and values need to be heard. EBP advocates could usefully learn from EBM about the importance of context and individual variation in situations, the expertise of decision-makers, and technical advice on how to interpret research evidence for specific situations which may not be identical to research settings. As we have shown, EBP can learn from EBM in recognising that a ‘horses for courses’ sensibility can help match knowledge requirements with appropriate methodological approaches (Parkhurst and Abeysinghe, 2016; Petticrew and Roberts, 2003). This may should, in theory, also include public interests occasions, or the deployment of other methods on other occasions. EBM has come to mean the integration of individual clinical expertise with external clinical evidence (Sackett et al., 1996), with patient experience and perspectives (Stefanie Ettelt and Mays, 2011; Greenhalgh and Hurwitz, 1999; Trisha Greenhalgh, 2016; Green and Thorogood, 2009; Pope and Mays, 1993), and the standardisation of the profession through formal structures (Greenhalgh et al., 2014). One formative EBM text frames the inclusive nature of modern EBM as a way to ‘help’ the experienced medic, rather than overrule them with science (Sackett et al., 1996).

In addition, EBM has exerted considerable effects to include a greater range of stakeholders in both the production of new evidence (i.e., the research process), and the use of this evidence. Lay members are part of groups which develop clinical practice recommendations after deliberating on the evidence, and Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) boards in health and social care aim to move beyond research participation to actively involve patients and public as advisers in the research process, or possibly co-researchers (National Institute of Health Research, 2014). In short, PPI shifts research from something done ‘to’, ‘for’ or ‘about’ the public to an activity done ‘with’ or ‘by’ the public (Boote et al., 2010)

EBP can also be seen as a site of negotiation, between the historic challenges of balancing multiple perspectives, and more recent efforts to increase public participation and introduce greater rigour into evidence production. While policymaking is sometimes framed as an elite activity (Haas, 1992; Rhodes and Marsh, 1992; Scott, 2001), democratic processes should, in theory, also include public interests, either through representation by elected politicians or by more direct participation. Advocates of greater civil inclusion in policy research and processes argue that there is an instrumental and moral value to including lay people (Epstein et al., 2014; Jasanoff, 2003; Wynne, 1992). Others interpret this as a repudiation of expertise (Kuntz, 2012, 2016), even leading one political scientist to call for democracy to be replaced by epistocracy, ‘rule by the knowledgeable’(Brennan, 2016). In general, however, greater public participation and ‘open policymaking’ is becoming the norm (Burall et al., 2013; Burgess, 2014; Pallett, 2015). In practice, this trend faces the same problem as EBM: how to properly consider ‘lay’ perspectives that may differ radically from evidence provided by well-established sources. Finding ways to include civil society and other interests in democratic processes is challenging, time consuming, and arguably at odds with the smooth running of government. Similarly, in an era of ‘big politics’ many members of the public are feeling increasingly disempowered and therefore disinclined to participate in official inputs to policy (Bang, 2009; Flinders and Dommett, 2013; McCluskey et al., 2004). Despite the growth in knowledge production institutions like the What Works Centres, the structures set up to support EBP, and in particular the strategies employed by these structures, are much less explicitly delineated than the cognate structures for EBM

Lesson three: understand how power shapes knowledge production and use

Some have begun to use policy studies to explore the importance and dynamics of power, inclusivity and advocacy (e.g., Cairney, 2017; Liverani et al., 2013; Pearce, 2014; Wesselink et al., 2014; Head, 2008). Acknowledging the importance of power, however, has not yet been taken on board by practitioners when developing strategies to support evidence informed decision-making (Fafard, 2015; Head, 2010; Murphy and Fafard, 2012; Parkhurst, 2017b; Smith, 2013a).

As indicated above, practitioners of EBM recognise that there are power imbalances between researchers and the public; and between practitioners and patients. However, merely recognising such power differentials does not tell us how to negotiate them appropriately, particularly in terms of how to assign legitimacy to the evidence provided by each stakeholder (researcher; professional; patient), or about the circumstances under which it is appropriate to rely on the experience of one stakeholder over another. While EBM provides a forum for shared discussion and sense-making, the navigation of social hierarchies is uncharted territory.

The response to this dilemma has been to produce new and inclusive structures for the production of knowledge (through co-productive approaches) and for its implementation and use (through inclusion of stakeholders in guideline development groups). It is often assumed, that “appropriate” evidence, filtered and nuanced in the right way by the right actors (often termed “deliberative approaches” or “public deliberation” by scholars in the field), consensus is possible (for example, see Conklin et al., 2008; Duke, 2016; Smith, 2013b).

Yet, although new structures can formalise processes of decision-making, they do not necessarily lead to inclusion of a diverse (or appropriate) set of expert voices. Recruitment to stakeholder/advisory groups or decision-making committees is rarely a transparent process, and often by invitation. Moreover, treating participants in a deliberative process as ‘representatives’ of an (unclear) population is unfair, yet recognising their individual histories and agendas is almost impossible to square with the ideal of value-free, methodologically rigorous decision-making. Finally, consensus is seen as a desirable goal, which indicates that power has been balanced and evidence appropriately considered and used (Horst and Irwin, 2010). We dispute all these assumptions, and suggest that consensus may not always be possible (Hendriks, 2009) and that the effects of consensus-seeking can vary depending on political systems and cultures (Dryzek and Tucker, 2008). Indeed, terms such as ‘evidence uptake’ or ‘improvement of evidence use’ mask the complexities and politics of knowledge transfer (Parkhurst, 2017a)Footnote 3

Increased sensitivity to competing values and policy frames in society can help reconnect policymaking to its inescapably political context, an approach that stands in opposition to the technocratic orientation of EBP (Hawkins and Parkhurst, 2015; Parsons, 2002). As well as producing and utilising appropriate knowledge, maximising the use of evidence ultimately boils down to the importance of human judgement. Just as medical professionals have to judge the applicability of the available evidence to a patient, so policy experts must act as mediators between the knowledge base and policy problem (Grundmann, 2017; Ingold and Varone, 2012; Turnhout et al., 2013). EBM can therefore offer an active research agenda, but provides few lessons to EBP on reconciling different perspectives.

How can we better understand how, and why power matters?

We suggest that means looking at the entire system of ‘epistemic governance’ to better understand how knowledge is produced and used by decision-makers (Pearce and Raman, 2014). For instance, how issues are framed, and how politicised they become, affects what knowledge will be considered legitimate and credible, which research is commissioned and used, and who becomes authoritative and powerful (Hartley et al., 2017, Brown 2015). Both EBM and EBP impose political agendas by impelling practitioners to make choices based on the available research. For example, health policy research focuses on reducing morbidity and mortality, rather than, for instance, problematizing and understanding the roles of social categories (Liverani et al., 2013; Parkhurst and Abeysinghe, 2016). If we see evidence production as driven by ease rather than public need, this raises important question about how research agendas are set; about how the knowledge production system operates; and of whether researchers should be open about their political values or the envisaged political endgame of their research (Pielke Jr., 2007).

This implies that future approaches to evidence use must go beyond calls for more structures or greater methodological pluralism. Instead we need better heuristics to determine what kinds of evidence are needed and for what purposes, considering the kinds of question being asked, the actions which may be taken as a result, and the politicisation of the problem. One potential way to navigate these complex issues is to consider some types of question being asked, and how this might affect the type of evidence being used. Examples may include:

-

1.

What is the nature of this problem?

-

2.

What have others done?

-

3.

How do I win this argument?

-

4.

This is new, what do I do?

The substantive topic in question will affect which types of evidence are required to answer, a dynamic unrecognised within many hierarchies of evidence and evidence appraisal systems (such as GRADE). For example, a doctor may observe a new response to a drug, or a new combination of symptoms (Q type 3). This may be highly political (e.g., huge increase in presentation of gender dysphoria in a small community) or uncontroversial (such as a new side effect of a drug). The question “what do I do?” will need very different consideration for both these situations. Similarly, it is possible to imagine situations in both medicine and policy where there is a desire to ‘win an argument’, but marshalling the appropriate evidence will depend on the actors involved, the politicisation of the topic in question, and so forth.

Politicisation of the topic in question is an under-explored facet of the ‘evidence-based’ paradigm, and one which gets to the heart of the technocratic/democratic tensions in the ideology (van Eeten, 1999). This is at least partly by design. Presenting the EB process as value-free, methodologically driven, and uncontroversial allows decision-makers to de-politicise potentially risky debates, and disarms potential opponents by making it harder to challenge (Boswell, 2017). One reason for EBP coming to such prominence in the New Labour years may be that Blair was more fearful of a predominantly right-wing press than previous governments, helping to drive the depoliticisation of knowledge production and utilisation (Parsons, 2002). While EBM’s new structures focused on co-producing evidence through new methods, EBP’s new structures looked to tame existing methodological pluralism as a means of legitimising decision-making, through producing and legitimising evidence in a way which reduced the scope for political attack and was amenable to the trend for ‘joined-up government’ (Davies, 2009).

Conclusions

We have summarised major trends in the literature on EBP and EBM and identified three key lessons for practitioners and commentators in both. Yet, implicit in the research and solutions (brokers, collaborative structures, shared power and decision-making) of both EBP and EBM is that a mix of appropriate evidence, experts, processes and structures will lead to improved decision-making. In fact, we do not know whether collaborative or co-productive research structures lead to more effective decision-making, or even better research. EBP and EBM are clearly different in terms of the machinery of decision-making, the types and number of actors involved, the structural constraints, the range of decisions to be taken and the diversity of evidence requiring consideration. Yet, constructing EBP as similar to EBM is understandable; it is a cipher connoting a recognisable process, and comes with a ready-made set of polemical devices and methodological tools. While both EBM and EBP share a desire to use evidence more effectively in decision-making, unpacking the history, decision-making processes and responses to some of the methodological and political challenges encountered by each, we have demonstrated that there are also fundamental differences. Using a typology of questions as a lens to consider which kinds of evidence may be useful, shows us that politicisation of a policy issue, alongside methodological concerns, influences what is considered credible and useful evidence. Advocates concerned with increasing evidence uptake, in either field, should draw on ideas about politicisation and legitimacy when devising strategies to increase research use.

As our discussion on politicisation shows, whenever a decision is taken, a problem must be framed in order to bound any discussion. This process of framing is an expression of power, and informs the selection of evidence types which will be used in any discussion (Boswell, 2014; van Hulst and Yanow, 2014). Yet, rare indeed is the expression of power which does not lead to the prioritisation of some interests over others. Thus, we contend that conflict is an inevitable part of both policy and clinical practice, due to the values and perceptions of the actors involved in each. Collaborative decision-sharing structures are, while a nice idea, still subject to the same group dynamics, personal biases and relationships as any other human interaction (Hendriks, 2009). Neither have we solved the problem of how far researchers should go to influence debates about policy and practice, without compromising their neutrality and commitment to strict empiricism (Cairney and Oliver, 2017; Smith and Stewart, 2017).

Thus, while much has been learned over the previous decades, we still do not understand well how the power dynamics of knowledge production inform evidence use, which forms of interaction between evidence users and producers are most productive, or the impact of evidence use on policy or patient outcomes. We argue that key dimensions for future enquiry include: understanding what evidence is and is not produced, who produces evidence, how evidence is framed, how evidence is incorporated into decision-making processes, and how all of these dimensions may be influenced by the types of problems policymakers and clinicians seek to solve. These are the outstanding questions for the field.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this paper as no datasets were generated or analysed.

Notes

We note that there is a large and complex literature on evidence use (for example, Weiss, 1979; Nutley et al., 2007; Parkhurst and Abeysinghe, 2016), discusses what use ‘might’ be. This is of course fundamental to consider before addressing questions about what should be used, and how to ‘maximise’ it. However, we think this question is too complex to be properly addressed in the scope of this paper.

References

Ansari MT, Tsertsvadze A, Moher D (2009) Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations: a perspective. PLoS Med https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000151

Armstrong R et al. (2013) Knowledge translation strategies to improve the use of evidence in public health decision making in local government: intervention design and implementation plan. IS 8:121. http://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-121

Bang H (2009) Political community: the blind spot of modern democratic decision-making. Br Polit 4(1):100–116. https://doi.org/10.1057/bp.2008.38

Banks G (2009) Evidence-based policy making: what is it? how do we get it? (ANU Public Lecture Series, presented by ANZSOG, 4 February). Australian Government Productivity Commission, Canberra

Baron J (2009) Randomized trials: a way to stop ‘spinning wheels’? Education Week 29(03):32

Beresford P (2000) Service users’ knowledges and social work theory: conflict or collaboration? Br J Social Work 30(4):489–503. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/30.4.489

Boaz A, Baeza J, Fraser A (2011) Effective implementation of research into practice: an overview of systematic reviews of the health literature. BMC Res Notes 4:212. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-4-212

Boote J, Baird W, Beecroft C (2010) Public involvement at the design stage of primary health research: A narrative review of case examples. Health Policy 95(1):10–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.11.007

Boote J, Telford R, Cooper C (2002) Consumer involvement in health research: a review and research agenda. Health Policy 61(2):213–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-8510(01)00214-7

Boswell J (2014) ‘Hoisted with our own petard’: evidence and democratic deliberation on obesity. Policy Sci 47(4):345–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-014-9195-4

Boswell J (2017) What makes evidence-based policy making such a useful myth? The case of NICE guidance on bariatric surgery in the United Kingdom. Governance. Online First: 26 April 2017, https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12285

Brennan J (2016) Against democracy. Princeton University Press, Princeton, USA

Brown MB (2015) Politicizing science: conceptions of politics in science and technology studies. Social Stud Sci 45(1):3–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312714556694

Burall S, Hughes T, Stilgoe J (2013) Experts, publics and open policy-making: opening the windows and doors of Whitehall. Sciencewise, London, England

Burgess MM (2014) From ‘trust us’ to participatory governance: deliberative publics and science policy. Public Underst Sci 23(1):48–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662512472160

Cabinet Office (1999) Professional policy-making for the twenty-first century. Cabinet Office, London

Cairney P (2012) Understanding public policy. Theories and issues. https://doi.org/JK468 P64 D95 2013

Cairney P (2017) Evidence-based best practice is more political than it looks: a case study of the ‘Scottish Approach’. Evidence and Policy 13(3):9–10. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426416X14609261565901

Cairney P, Oliver K (2017) Evidence-based policymaking is not like evidence-based medicine, so how far should you go to bridge the divide between evidence and policy? Health Res Policy Syst 15(1):35

Campbell S, Benita S, Coates E, Davies P, Penn G (2007) Analysis for policy: evidence-based policy in practice. HM Treasury, London

Cartwright N (2007) Are RCTs the gold standard? BioSocieties 2(1):11–20.

Cochrane AL (1972) Effectiveness and efficiency: random reflections on health services. The Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7438.529

Conklin A, Hallsworth M, Hatziandreu E, Grant J (2008) Briefing on linkage and exchange: facilitating diffusion of innovation in health services. Rand Occasional Paper, Rand, UK

Davies JS (2009) The limits of joined-up government: towards a political analysis. Public Adm 87(1):80–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2008.01740.x

Dobbins M, Hanna SE, Ciliska D, Manske S, Cameron R, Mercer SLSL, Robeson P (2009) A randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of knowledge translation and exchange strategies. Implement Sci 4(61):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-61

Dobrow MJ, Goel V, Upshur REG (2004) Evidence-based health policy: context and utilisation. Soc Sci Med 58(1):207–217

Dryzek JS, Tucker A (2008) Deliberative innovation to different effect: consensus conferences in Denmark, France, and the United States. Public Adm Rev 68(5):864–876. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2008.00928.x

Duke K (2016) Exchanging expertise and constructing boundaries: the development of a transnational knowledge network around heroin-assisted treatment. Int J Drug Policy 31:56–63

Epstein D, Farina C, Heidt J (2014) The value of words: narrative as evidence in policy making. Evid Policy 10(2):243–258. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426514X13990325021128

Ettelt S, Mays N (2011) Health services research in Europe and its use for informing policy. J Health Serv Res Policy 16 Suppl 2:48–60 https://doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2011.011004

Ettelt S, Mays N, Allen P (2015) Policy experiments: investigating effectiveness or confirming direction? Evaluation 21(3):292–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389015590737

Fafard P (2015) Beyond the usual suspects: using political science to enhance public health policy making. J Epidemiol Community Health 69:1129–1132. http://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-204608

Flinders M, Dommett K (2013) Gap analysis: participatory democracy, public expectations and community assemblies in Sheffield. Local Gov Stud 39(4):488–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2012.751023

Freiberg A, Carson WG (2010) The limits to evidence-based policy: evidence, emotion and criminal justice. Aust J Public Adm 69(2):152–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8500.2010.00674.x

Freudenberg N, Tsui E (2013) Evidence, power, and policy change in community-based participatory research. Am J Public Health 104(1):11–14. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301471

Gold M (2009) Pathways to the use of health services research in policy. Health Serv Res 44(4):1111–1136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00958.x

Greenhalgh T (2016) Cultural contexts of health: the use of narrative research in the health sector. Health Evidence Network Synthesis Report 49. The Health Evidence Network

Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N (2014) Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? BMJ 348:g3725. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g3725

Greenhalgh T, Hurwitz B (1999) Narrative based medicine: why study narrative? BMJ 318(7175):48–50. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.318.7175.48

Green J, Thorogood N (2009) Qualitative methods for health research. Introducing qualitative methods. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305285708

Grundmann R (2017) The problem of expertise in knowledge societies. Minerva. 55(1):25–48

Grundmann R, Stehr N (2012) The power of scientific knowledge: from research to public policy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Haas PM (1992) Introduction: epistemic communities and international policy coordination. Int Organ 46(1):1–35

Hammersley M (2007) The issue of quality in qualitative research. Int J Res Method Educ 30(3):287–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437270701614782

Hartley S, Pearce W, Taylor A (2017) Against the tide of depoliticisation: the politics of research governance. Policy Polit 45(3):361–377. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557316X14681503832036

Hawkins B, Parkhurst J (2015) The ‘good governance’ of evidence in health policy. Evid Policy 12(4):575–592. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426415X14430058455412

Haynes L, Service O, Goldacre B, Torgerson D (2012) Test, learn, adapt: developing public policy with randomised controlled trials. cabinet office-behavioural. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2131581

Head BW (2008) Three lenses of evidence‐based policy. Aust J Public Adm 67(1):1–11

Head BW (2010) Reconsidering evidence-based policy: key issues and challenges. Policy Soc 29(2):77–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2010.03.001

Head BW (2017) Policy-relevant research: improving the value and impact of the social sciences. Soc Sci Sustain 1:199

Hendriks CM (2009) Deliberative governance in the context of power. Policy Soc 28(3):173–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2009.08.004

Horst M, Irwin A (2010) Nations at ease with radical knowledge: on consensus, consensusing and false consensusness. Social Stud Sci 40(1):105–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312709341500

Ingold K, Varone F (2012) Treating policy brokers seriously: evidence from the climate policy. J Public Adm Res Theory 22(2):319–346. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mur035

Innvaer S, Vist G, Trommald M, Oxman A (2002) Health policy-makers’ perceptions of their use of evidence: a systematic review-innvaer systematic review.pdf. J Health Serv Res & Policy 7(4):239–44. https://doi.org/10.1258/135581902320432778

Jasanoff S (2003) Technologies of humility: citizen participation in governing science. Minerva 41:223–244

Kalil T (2014) Funding what works: the importance of low-cost randomized controlled trials. whitehouse.gov. White House Archives. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2014/07/09/funding-what-worksimportance-low-cost-randomized-controlled-trials

Kuntz M (2012) The postmodern assault on science. EMBO Rep 13(10):885–889

Kuntz M (2016) Scientists should oppose the drive of postmodern ideology. Trends Biotechnol 34(12):943–945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.08.008

Laura and John Arnold Foundation (2016) Key items to get right when conducting randomized controlled trials of social programs. Laura and John Arnold Foundation

Lin V (2003) Competing rationalities: evidence-based health policy? in: Lin V, Gibson B (eds) Evidence-based health policy: Problems & Possibilities. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p 3–17

Liverani M, Hawkins B, Parkhurst JO (2013) Political and institutional influences on the use of evidence in public health policy. A systematic review. PloS One 8(10):e77404. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077404

Marmot MG (2004) Evidence based policy or policy based evidence? BMJ 328:906–907. https://doi.org/doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7445.906

McCluskey MR, Deshpande S, Shah DV, McLeod DM (2004) The efficacy gap and political participation: when political influence fails to meet expectations. Int J Public Opin Res 16(4):437–455. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edh038

Montori VM, Guyatt GH (2008) Progress in evidence-based medicine. Jama 300(15):1814–1816

Murphy K, Fafard P (2012) Taking power, politics, and policy problems seriously. J Urban Health 89(4):723–732

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2014) The guideline development process: an overview for stakeholders, the public and the NHS. National Institute for Clinical Excellence, London, England

National Institute of Health Research Research Design Service (2014) Patient and public involvement in health and social care research: a handbook for researchers. National Institute of Health Research, UK

Nutley SM, Walter I, Davies HT (2007) Using evidence: How research can inform public services. Policy Press, Bristol

Oakley A (2000) A historical perspective on the use of randomized trials in social science settings. Crime Delinquency 46(3):315–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128700046003004

Oliver K, de Vocht F (2017) Defining ‘evidence’ in public health: a survey of policymakers’ uses and preferences. Eur J Public Health ckv082. 27(2): 112–117

Oliver K, Everett M, Verma A, de Vocht F (2012) The human factor: re-organisations in public health policy. Health Policy 106(1):97–103

Oliver K, Innvaer S, Lorenc T, Woodman J, Thomas J (2013) Barriers and facilitators of the use of evidence by policy makers: an updated systematic review. manchester.ac.uk.

Oliver K, Innvar S, Lorenc T, Woodman J, Thomas J (2014) A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Serv Res 14(1):2.

Oliver K, Lorenc T (2014) New directions in evidence-based policy research: a critical analysis of the literature. Health Res Policy Syst 12(14):34

Oliver S (2006) Patient involvement in setting research agendas. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 18(9):935–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.meg.0000230089.68545.45

Oliver S, Bagnall A-M, Thomas J, Shepherd J, Sowden A, White I, Oliver K (2010) Randomised controlled trials for policy interventions: a review of reviews and meta-regression. Health Technol Assess Monogr 14(16):3–165

Orton L, Lloyd-Williams F, Taylor-Robinson, D, O’Flaherty M, Capewell S (2011) The use of research evidence in public health decision making processes: systemic review. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0021704

Pallett H (2015) Public participation organizations and open policy: a constitutional moment for British democracy? Sci Commun 37(6):769–794. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547015612787

Parkhurst JO (2017a) Mitigating evidentiary bias in planning and policy-making; comment on ‘reflective practice: how the world bank explored its own biases?’. Int J Health Policy Manag 6(2):103–105. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2016.96

Parkhurst JO (2017b) The politics of evidence: from evidence-based policy to the good governance of evidence. Routledge, New York, NY, Abingdon, Oxon

Parkhurst JO, Abeysinghe S (2016) What constitutes ‘good’ evidence for public health and social policy-making? From hierarchies to appropriateness. Soc Epistemol 30(5-6):665–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2016.1172365

Parsons W (2001) Modernising policy-making for the twenty first century: the professional model. Public Policy Adm 16(3):93–110

Parsons W (2002) From muddling through to muddling up-evidence based policy making and the modernisation of British government. Public Policy Adm 17(3):43–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/095207670201700304

Pawson R (2002) Evidence-based policy: the promise of ‘realist synthesis’. Evaluation 8(3):340–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/135638902401462448

Pearce W (2014) Scientific data and its limits: rethinking the use of evidence in local climate change policy. Evid Policy 10(2):187–203. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426514X13990326347801

Pearce W, Grundmann R, Hulme M, Raman S, Kershaw EH, Tsouvalis J (2017) Beyond counting climate consensus. Environ Commun 0(0):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2017.1333965

Pearce W, Raman S (2014) The new randomised controlled trials (RCT) movement in public policy: challenges of epistemic governance. Policy Sci 47(4):387–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-014-9208-3

Pearce W, Raman S, Turner A (2015) Randomised trials in context: practical problems and social aspects of evidence-based medicine and policy. Trials 16(1):394. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-0917-5

Petticrew M, Roberts H (2003) Evidence, hierarchies, and typologies: horses for courses. J Epidemiol Community Health 57(7):527–529. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.57.7.527

Pielke Jr, R A (2007) The honest broker: making sense of science in policy and politics. Cambridge University Press, USA

Pope C, Mays N (1993) Opening the black box: an encounter in the corridors of health services research. Br Med J 306(6873):315–318. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.306.6873.315

Rhodes RAW, Marsh D (1992) New directions in the study of policy networks. Eur J Political Res 21(1–2):181–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1992.tb00294.x

Russell J, Greenhalgh T, Byrne E, McDonnell J (2008) Recognizing rhetoric in health care policy analysis. J Health Serv Res Policy 13(1):40–6. https://doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2007.006029

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM, Haynes RB, Richardson WS (1996) Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 312(7023):71–72. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71

Sarewitz D (2009) The rightful place of science. Issues Sci Technol 25(4):89–94

Sarewitz D, Foladori G, Invernizzi N, Garfinkel MS (2004) Science policy in its social context. Philos Today 48(Supplement):67–83

Scott J (2001) Power (key concepts). Polity

Sibbald B, Roland M (1998) Understanding controlled trials. Why are randomised controlled trials important? BMJ 316(7126):201

Smith K (2013a) Beyond evidence based policy in public health: The interplay of ideas. Springer, UK

Smith K (2013b) Institutional filters: the translation and re-circulation of ideas about health inequalities within policy. Policy Polit 41(1):81–100. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557312X655413

Smith KE (2014) The politics of ideas: the complex interplay of health inequalities research and policy. Sci Public Policy 41(5):561–574. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/sct085

Smith KE, Stewart EA (2017) Academic advocacy in public health: disciplinary ‘duty’or political ‘propaganda’? Social Sci Med 189:35–43

Stewart RJ, Caird J, Oliver K, Oliver S (2011) Patients’ and clinicians’ research priorities. Health Expectations 14(4):439–448

Turnhout E, Stuiver M, Klostermann J, Harms B, Leeuwis C (2013) New roles of science in society: different repertoires of knowledge brokering. Sci Public Policy 40:354–365

van Eeten MJG (1999) ‘Dialogues of the deaf’ on science in policy controversies. Sci Public Policy 26(3):185–192. https://doi.org/10.3152/147154399781782491

van Hulst M, Yanow D (2014) From policy ‘frames’ to ‘framing’ theorizing a more dynamic, political approach. Am Rev Public Adm 46(1):92–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074014533142

Victora CG, Habicht J-P, Bryce J (2004) Evidence-based public health: moving beyond randomized trials. Am J Public Health 94(3):400–405. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.3.400

Ward V (2017) Why, whose, what and how? A framework for knowledge mobilisers. Evidence Policy 13(3):477–497 https://doi.org/10.1332/174426416X146347632787

Weiss CH (1979) The many meanings of research utilization. Public Adm Rev 39(5):426. https://doi.org/10.2307/3109916

Weiss CH (1991) Policy research as advocacy: pro and con. Knowl Policy 4(1):37–55

Wesselink A, Colebatch H, Pearce W (2014) Evidence and policy: discourses, meanings and practices. Policy Sci 47(4):339–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-014-9209-2

Wynne B (1992) Misunderstood misunderstanding: social identities and public uptake of science. Public Underst Sci 1(3):281–304. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-6625/1/3/004

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oliver, K., Pearce, W. Three lessons from evidence-based medicine and policy: increase transparency, balance inputs and understand power. Palgrave Commun 3, 43 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0045-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0045-9

This article is cited by

-

eHealth policy framework in Low and Lower Middle-Income Countries; a PRISMA systematic review and analysis

BMC Health Services Research (2023)

-

Pandemics, policy, and pluralism: A Feyerabend-inspired perspective on COVID-19

Synthese (2022)

-

The People-Centred Approach to Policymaking: Re-Imagining Evidence-Based Policy in Nigeria

Global Implementation Research and Applications (2022)

-

What counts? Policy evidence in public hearing testimonies: the case of single-payer healthcare in New York State

Policy Sciences (2022)

-

Follow *the* science? On the marginal role of the social sciences in the COVID-19 pandemic

European Journal for Philosophy of Science (2021)