Abstract

Visual-related quality of life in retinal diseases has not been explored in the Mexican population, so the study aims to identify it in patients undergoing surgery due to advanced diabetic retinopathy, rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, and other causes of vitrectomy; the Visual Function Quality-25 questionnaire was applied to 76 patients, pre-and postoperative. It was divided into 10 domains and interpreted according to the National Eye Institute scores, where the highest value was the best visual function. Student's t-test for related samples and Wilcoxon’s t-test were used to compare each domain between measurements, and Pearson’s R test to correlate the total score of age and quality of life; a p value < 0.05 was considered significant. Diabetic retinopathy patients showed an improvement 1 and 3 months after surgery in all domains; in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, there was an improvement observed up to 3 months, while a decrease in ocular pain was observed in other causes of vitrectomy. Differences found in all the quality-of-life scores were not statistical, but clinically significant. The study shows that visual-related quality of life domains improves after vitrectomy; the inclusion of this analysis might be considered relevant within the parameters of surgical success of the most prevalent vitreoretinal diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines quality of life as the perception that an individual has in the context of their culture, the values in which they live, their expectations, norms, and concerns1. Consists of both objective components and material circumstances of life, for example, illness, pain, disability, and other factors added to subjective components that are mainly the degree of satisfaction and the perception of living conditions2.

Currently, it is not enough to assess the value of visual acuity and the visual field as surgical success, but the quality of life perceived after eye surgery must be included. There are some instruments to assess the quality of life and visual function, including The Visual Disability Assessment (VF-14)3, the Activities of Daily Vision Scale (AVDS)4, the Quality of Life Questionnaire (QOLQ)5, Visual Function Quality-39 (VFQ-39)6 and Visual Function Quality-25 (VFQ-25)7; the latter has demonstrated validity and reliability for different populations in distinct languages in the 25-item adaptation derived from the original 51-item8.

The questionnaire measures the influence of visual disability and visual symptoms in physical and mental health domains and those related to visual functioning, problems involving vision, or the patient’s perception of their vision condition9. It has been evaluated in Spanish10, for Latino patients living in the United States9, Cubans8, and Colombians11, where internal reliability coefficients are lower than those necessary in the items of general health and driving (so they are eliminated from the questionnaire in its Spanish version)8,10.

It has been translated and adapted to the cultural environment and validated in Serbian, Turkish, Chinese, Japanese, Greek, French, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, and Spanish9,10. Among the retinal pathologies in which it has been evaluated, Okamoto and his group12 report a higher preoperative and postoperative score for macular hole and epiretinal membrane and retinal detachment. The VQF-25 has become a tool that has been used to assess the quality of life in subjects with cataracts13, glaucoma14, age-related macular degeneration15, and diabetic retinopathy16, among others.

However, the VFQ-25 questionnaire in its Spanish version has not been applied to the most prevalent retinal pathologies in Mexico. Our objective was to identify the quality-of-life score related to vision in patients with vitreoretinal diseases who undergo retinal surgery in a reference ophthalmological hospital and determine which are the domains of quality of life with higher impact after surgery.

Methods

It is an observational, prospective, comparative, and longitudinal study. Seventy-six patients between 18 and 80 years, who had diabetic retinopathy, rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, and other vitreoretinal pathologies (macular hole, epiretinal membrane, and causes of vitreous hemorrhage) in one eye, were included by non-probabilistic sampling determined by time; patients with other pathologies such as cataracts or glaucoma that compromises the visual function were excluded. Patients were followed-up after a vitrectomy at 1 and 3 months in person or by telephone between May and August 2019; they agreed to participate, understood, and signed the informed consent. This study followed the principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the hospital where it took place. The data was handled and analyzed with strict confidentiality and according to good practices.

The demographic variables considered were age and sex, and the best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was recorded before the intervention, which was converted to the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) for statistical calculations. Within the approximations, finger count was considered as 20/2000, hand movement = 20/4000, and light perception = 20/8000.

The researchers applied the Visual Function Quality-25 test; the questionnaire was divided into 10 domains: (1) general vision, (2) eye pain, (3) close activities, (4) distance activities, (5) social functioning, (6) mental health, (7) role limitations, (8) dependence, (9) color vision, and (10) peripheral vision. The Spanish version excludes the general health and driving items from the algorithm, for which there are 23 items8; its application time was less than 15 min. The researchers explained the questionnaire to the patients at the beginning of the application and provided additional support when necessary.

For the calculation and interpretation of the results, the National Eye Institute (NEI) scoring algorithm was used17, which considers the subscales with a score from 0 to 100, where 100 is the highest function. The total score was the mean of all items; in case an answer to a question was not related to vision or did not apply to the context, it was excluded from the overall score.

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistical test evaluated the data distribution; only items 3, 7, and 8 in the diabetic retinopathy group did not have a normal distribution. The means of each domain with missing data imputed by the last observation carried forward (LOCF) were compared using Student’s t-test for related samples and Wilcoxon’s t-test, as appropriate, and the variable quality of life total score between the different types of tamponades was calculated using Kruskal–Wallis. Also, the correlation coefficient of the total score concerning age was obtained by Pearson’s R test, which considered an r < 0.4 as a weak correlation, r ≥ 0.4–0.7 as moderate, and r > 0.7 as a strong correlation; a p value < 0.05 was considered significant. Data were stored and analyzed in GraphPad Prism version 8.0 for Mac.

Ethics approval

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Fundación Hospital Nuestra Señora de la Luz IAP. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Results

Of the presurgical sample, the mean age was 50.4 ± standard deviation (S.D.) 10.19 years, 44 men (57.89%) and 32 women (42.11%); 54% of the patients undergoing surgery for advanced diabetic retinopathy (n = 41), 30% for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (n = 23), and 12% for other causes of vitrectomy (n = 12).

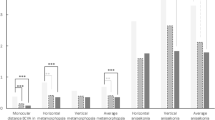

Forty-one patients diagnosed with advanced diabetic retinopathy aged 53.27 years ± 9.06; 61% (n = 25) were men. For this group, the preoperative quality-of-life total score was 43.01 ± 18.19 points, after 1 month 57.62 ± 20.95, and at 3 months 59.17 ± 19.11 (Table 1); the rest of the items also showed improvement in quality of life at 1 month, although the subjects evaluated reported higher ocular pain after surgery than before it (p < 0.001). This statistical difference persisted when the pre-surgical evaluation was compared with the 3 months follow-up after the intervention, except in the general vision and social performance items, although in both cases quality of life improved.

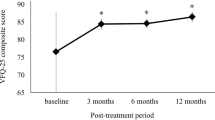

Neither of the cases had a significant difference in the scores obtained when the 1-month and 3 months after surgery; there was also no difference between sex and the quality-of-life total score before surgery (p = 0.27), at 1 month (p = 0.93), and 3 months (p = 0.18). Regarding the type of tamponade, there was a higher quality of life pre-surgical score when the tamponade was air/gas versus silicone (p = 0.04). The correlation between age and the pre-surgical total score had a weak positive linear correlation (r = 0.15, p = 0.34), but this changed when evaluating the total score 1 month (r = 0.43) and 3 months (r = 0.47) after surgery, where existed moderate positive correlations with statistical significance (p < 0.05, Figs. 1, 2).

In patients undergoing surgery for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, the mean age was 51.43 ± 12.31 years; 61% (n = 14) were men. The evaluation included 15 right eyes and eight left eyes. The higher quality of life scores were mental health and role difficulty items 1 month after surgery compared to the pre-surgical evaluation (p < 0.05, Table 2); however, the difference did not appear between the two post-surgical total scores. Five items showed significant improvement 3 months after surgery, and only the ocular pain variable had a higher score before surgery. There was also no change at 1 month and 3 months after surgery in the pre-surgical total score concerning patient sex or the type of tamponade (p > 0.05). In the correlation analysis, existed negative linear relations between age and the total score at 1 month (r = -0.44) and 3 months (r = -0.27), although there was no statistical difference (p > 0.05).

Regarding other causes of vitrectomy analyzed, the mean age was 53.17 ± 10.12 years; 58.3% (n = 7) were women. The evaluation included 11 right eyes and one left. The quality-of-life total score was 56.14 ± 10.11 before surgery, 66.49 ± 18.63 at 1 month, and 63.59 ± 24.59 at 3 months. Only the ocular pain variable showed a higher quality of life after surgery with statistical significance when compared with pre-surgical evaluation (Table 3). Quality-of-life items compared with the type of tamponade or patient sex had no difference but a weak positive correlation between age and the pre-surgical total score, not significant (r = 0.17, p = 0.59).

Discussion

Our study found an increase in quality of life 1 month after vitrectomy in each group and increased up to 16 points when compared to pre-surgical vision quality versus 3 months after vitrectomy evaluation, in patients with advanced diabetic retinopathy, 9 points in patients with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, and 6 points in patients undergoing surgery for other reasons. The type of air/gas tamponade showed a better quality of life score compared to those in which silicone was used, this may be because its use is generally limited to the most complex retinal disease cases who perceive a lower quality of life-related to vision; additionally, a correlation was identified between older age and an improvement in the quality-of-life score after surgery, particularly in patients with diabetic retinopathy.

These findings contrast with the reported by Okamoto and his group18, who applied the test to 51 patients diagnosed with diabetic retinopathy before undergoing surgery and 3 months later; the score reported in vitreous hemorrhage was 51.2 to 62.3, tractional retinal detachment 61.1 to 70.3 and excessive macular traction 55.2 to 59.4. The subscales that reported significant improvement after surgery were general vision, near and distance activities, social function, mental health, role difficulty, driving, and peripheral vision. However, no correlation was shown with age, duration of diabetes, HbA1C levels, or fasting glucose. Our study observed that the preoperative score was below the reported by Okamoto (43.00); however, the results after surgery are similar (57.51 and 59.17), indicating a significant improvement in the quality of life of patients undergoing vitrectomy in our country.

The quality-of-life total score in cases of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment has been reported at 80 points in women and 74.7 in men with follow-up at 6 months; according to Smeretschnig, the items with the greatest difference concerning normal controls were general vision, mental health, social functionality, driving, and color vision20. On the other hand, a group reported this difference at 3 months of operated patients versus controls, in near activities, peripheral vision, dependency, and mental health19, whose findings coincide with those of Du and his team21, although the latter applied the questionnaire one day before surgery. We compared the same patients over time and found a significant difference in the composite score, regarding mental health and role difficulty during the first month, while at 3 months these same variables are preserved, general vision showed an improvement, and eye pain, color vision, and peripheral vision scores decreased; it may be possible that the changes reported in each item are higher the more time passes after surgery, but this requires an additional long-term study.

In epiretinal membranes, vitrectomy has significantly improved the components of quality of life, being the most important post-surgical improvement among the pathologies studied12. It mainly impacts 10 subscales except for peripheral vision and general health (mean score 77.9). The results seem to be directly related to the presence and severity of preoperative metamorphopsia, but not visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, or central macular thickness22. On the contrary, Ghazi reports that there is an improvement of the metamorphopsia perception after surgery, and considers that the initial visual acuity correlates with the initial VFQ-25 score; however, in his study, VA does not improve considerably after surgery, and only remote activities, general vision, and the overall score had an improvement23. Matsuoka24 has reported that the greatest improvement-related items at 3 months after surgery are visual capacity, general vision, close activities, role difficulties, and the composite score, while at 12 months it is the improvement of the metamorphopsia-perception, general vision, close activities, distance activities, mental health, role difficulty, and the composite score. In this study, we found no difference in the pre-and post-surgical quality of life for this pathology, which was included in other causes of vitrectomy; the only item with a statistical difference was the eye pain that improved after surgery in the first month. However, further analysis is required to evaluate the quality of life and its correlation with the visual function test.

It is important to consider the quality of life as one of the variables within surgical success that are observed to increase, after surgery for retinal pathologies, which is more noticeable in older patients (43% in the evolution at 1 month), and in 47% of the cases 3 months after the intervention, which represents a 30% of change concerning the quality of life prior the vitrectomy, according to our findings. The relevance lies in the high prevalence of these diseases in our population and their poor control; to our knowledge, it is the first report of quality of life-related to vision in patients undergoing vitrectomy in Mexico. However, we recognized that it is necessary to generate effective strategies for achieving a complete follow-up in all temporalities of the evaluation, to limit a possible bias along the analysis; this must be taken into account for further studies.

In conclusion, vitrectomy performed in patients with advanced diabetic retinopathy improves the quality-of-life score associated with vision and in each of the items from the first month after surgery, while for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, the relevant improvement is observed up to 3 months after surgery. Another prospective study with a long-term follow-up that considers vision and sensory tests is suggested, in addition to increasing the sample of patients.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Quality of life assessment group. Qué calidad de vida?. Foro Mundial de la Salud 17, 385–387 (1996).

Haraldstad, K. et al. A systematic review of the quality of life research in medicine and health sciences. Qual. Life Res. 28, 2641–2650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02214-9 (2019).

Khadka, J. et al. Translation, cultural adaptation, and Rasch analysis of the visual function (VF-14) questionnaire. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 55, 4413–4420. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.14-14017 (2014).

Gothwal, V. K., Wright, T. A., Lamoureux, E. L. & Pesudovs, K. Activities of daily vision scale: What do the subscales measure?. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 694–700. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.09-3448 (2010).

Albuquerque, C. P. Psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of the Quality of Life Questionnaire (QOL-Q). J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 25, 445–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2012.00685.x (2012).

Gothwal, V. K., Reddy, S. P., Sumalini, R., Bharani, S. & Bagga, D. K. National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire or Indian Vision Function Questionnaire for visually impaired: A conundrum. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 53, 4730–4738. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.11-8776 (2012).

Hirneiss, C., Schmid-Tannwald, C., Kernt, M., Kampik, A. & Neubauer, A. S. The NEI VFQ-25 vision-related quality of life and prevalence of eye disease in a working population. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 248, 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-009-1186-3 (2010).

Rodriguez-Suárez, B. et al. NEI VFG-25 scale as a measuring instrument of the vision-related quality of life. Rev. Cub de Oftal. 30, 1–12 (2017).

Broman, A. T. et al. Psychometric properties of the 25-item NEI-VFQ in a Hispanic population: Proyecto VER. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42, 606–613 (2001).

Alvarez-Peregrina, C. et al. Crosscultural adaptation and validation into Spanish of the questionnaire National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire 25. Arch. Soc. Esp. Oftalmol. (Engl. Ed.) 93, 586–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oftal.2018.05.017 (2018).

Palencia-Flores, D. C., Camacho-López, P. A. & Cáceres-Manrique, F. M. Confiabilidad de escala NEI VF-25 en una población colombiana con enfermedad crónica. Rev. Mex. Oftalmol. 90, 174–181 (2016).

Okamoto, F., Okamoto, Y., Fukuda, S., Hiraoka, T. & Oshika, T. Vision-related quality of life and visual function after vitrectomy for various vitreoretinal disorders. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 744–751. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.09-3992 (2010).

Wan, Y. et al. Validation and comparison of the National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire-25 (NEI VFQ-25) and the Visual Function Index-14 (VF-14) in patients with cataracts: A multicentre study. Acta Ophthalmol. 99, e480–e488. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.14606 (2021).

Moreno, M. N. et al. Quality of life and visual function in children with glaucoma in Spain. Arch. Soc. Esp. Oftalmol. (Engl. Ed.) 94, 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oftal.2018.09.001 (2019).

Jelin, E., Wisløff, T., Moe, M. C. & Heiberg, T. Psychometric properties of the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ 25) in a Norwegian population of patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration compared to a control population. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 17, 140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1203-0 (2019).

Pawar, S. et al. Assessment of quality of life of the patients with diabetic retinopathy using National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire (VFQ-25). J. Healthc. Qual. Res. 36, 225–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhqr.2021.02.004 (2021).

Mangione, C. M. et al. Development of the 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire. Arch. Ophthalmol. 119, 1050–1058. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.119.7.1050 (2001).

Okamoto, F., Okamoto, Y., Fukuda, S., Hiraoka, T. & Oshika, T. Vision-related quality of life and visual function following vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 145, 1031–1036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2008.02.006 (2008).

Okamoto, F., Okamoto, Y., Hiraoka, T. & Oshika, T. Vision-related quality of life and visual function after retinal detachment surgery. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 146, 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2008.02.011 (2008).

Smretschnig, E. et al. Vision-related quality of life and visual function after retinal detachment surgery. Retina 36, 967–973. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000000817 (2016).

Du, Y. et al. Vision-related quality of life and depression in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 98, e14225. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000014225 (2019).

Okamoto, F., Okamoto, Y., Hiraoka, T. & Oshika, T. Effect of vitrectomy for epiretinal membrane on visual function and vision-related quality of life. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 147, 869–874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2008.11.018 (2009).

Ghazi-Nouri, S. M., Tranos, P. G., Rubin, G. S., Adams, Z. C. & Charteris, D. G. Visual function and quality of life following vitrectomy and epiretinal membrane peel surgery. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 90, 559–562. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2005.085142 (2006).

Matsuoka, Y. et al. Visual function and vision-related quality of life after vitrectomy for epiretinal membranes: A 12-month follow-up study. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 53, 3054–3058. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.11-9153 (2012).

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, Grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by I.S.M.V., G.J.R.N., I.Y.P.O., H.J.P.C., and S.A.S.V. I.S.M.V., H.J.P.C., and S.A.S.V. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Márquez-Vergara, I.S., Ríos-Nequis, G.J., Pita-Ortíz, I.Y. et al. Vision-related quality of life after surgery for vitreoretinal disorders in a Mexican population: an observational study. Sci Rep 13, 4885 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32152-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32152-z

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.