Abstract

The number of vegans is increasing and was estimated at 2.0% of the Austrian population. Austrian vegans were found to have lower intakes and levels of vitamin B12 compared to vegetarians and omnivores. Vegans are advised to consume reliable sources of vitamin B12, e.g., in the form of dietary supplements or fortified foods. This study aimed to investigate health and supplementation behavior, with special emphasis on the supplementation of vitamin B12, and to demographically characterize the community of Austrian adult vegans. A nonrandom, voluntary sample of adult vegans with a principal residence in Austria was recruited with an online cross-sectional survey via social media and messenger platforms. Associations between respondent characteristics (gender, education, nutritional advice by a dietitian or nutritionist) and health/supplementation behaviors were examined by cross-tabulation. The questionnaire was completed by 1565 vegans (completion rate 88%), of whom 86% were female, the median age was 29 years, 6% were obese, and 49% had completed an academic education. Ninety-two percent consumed vitamin B12 through supplements and/or fortified foods, and 76% had their vitamin B12 status checked. The prevalence of vitamin B12 intake through supplements and/or fortified foods was slightly (not statistically significant) higher among women vs. men (93% vs. 89%), those who were academically educated vs. those who were not (93% vs. 91%), and those who had taken nutritional advice vs. those who had not (97% vs. 92%). Professional nutritional advice had been taken by only 9.5% of female and 8.4% of male respondents. Those who had taken advice reported a lower smoking prevalence (p = 0.05, φ = 0.05), higher prevalence of checking vitamin B12 status (p < 0.01, φ = 0.10), vit B12 intake through supplements and/or fortified foods (p = 0.03, φ = 0.05), and taking supplements of omega-3 (p < 0.01, φ = 0.14), selenium (p = 0.02, φ = 0.06), and iodine (p = 0.02, φ = 0.06). Austrian vegans can be characterized as predominantly young, female, urban, highly educated, and nonobese. The rate of vitamin B12 intake through supplements and/or fortified foods is fairly high (92%), but should be further improved e.g., by increasing the share of vegans who follow professional nutritional advice (requiring a diploma in dietetics, nutritional science, or medicine in Austria).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The number of vegans is increasing and was estimated to be 2.0% of the Austrian population in 20211, 1.6% in Germany in 20162, and 3.0% in the U.S. in 20203; these estimates were based on varying survey dates and assessment methodologies and are therefore not directly comparable. An Austrian survey conducted in 2016 found a higher share of women among later adopters (past 3 years) than among earlier adopters (83% and 65%, respectively) and that the average age at vegan diet adoption was approximately 25 years4. For 86% of Austrian vegans, ethical motives (e.g., regarding factory farming) are the main consideration for choosing a vegan diet, ahead of health-related motives5. The FAO’s food balance sheets show a substantial decline in the Austrian pig meat supply (− 31%) and a slight decline in the bovine meat (− 8%) and poultry (− 5%) supply from 2010 to 20196. It is the position of the US Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics that “appropriately planned vegetarian, including vegan, diets are healthful, nutritionally adequate, and may provide health benefits in the prevention and treatment of certain diseases. These diets are appropriate for all stages of the life cycle, including pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood, adolescence, older adulthood, and for athletes …”7. In contrast, the German Nutrition Society does not recommend a vegan diet for pregnant or breastfeeding women, babies, children, or adolescents in its position paper, due to uncertainty in research data8,9. However, the German Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Medicine stated that the nutritional needs of growing children and adolescents can generally be met through a balanced, vegetable-based diet10. Likewise, the Spanish Association of Paediatrics advises infants and young children to follow an omnivorous diet or, at least, an ovo-lacto-vegetarian diet11. Vegans may have lower intakes of vitamin B12 (henceforth “B12”), calcium, iodine, vit D, zinc, and long-chain omega-3 fatty acids12,13,14. Austrian vegans, in particular, were found to have lower intakes and levels of B12, vit B2, and calcium when compared to vegetarians and omnivores5. B12 status assessment and intake of reliable B12 sources, such as fortified foods or supplements, are recommended consistently to all vegans7,8,15. The EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA) set an adequate intake for B12 at 4 μg/day for adults; for pregnant and lactating women, adequate intakes of 4.5 and 5 μg/day, respectively, were proposed16. If pregnant and/or lactating vegan women do not habitually use reliable B12 sources, they also place their offspring at risk for B12 deficiency17. B12 (cobalamin) is synthesized by certain bacteria and archaea but not by plants or animals. The synthesized B12 is transferred to and accumulates in animal tissues and even certain plant tissues (e.g. algae) through microbial interactions18. B12 is an essential molecule for humans, with functions in fatty acid, amino acid, and nucleic acid metabolic pathways; hypovitaminosis arises from inadequate absorption, genetic defects, or inadequate dietary intake19. B12 deficiency can present with nonspecific clinical features and in severe cases with neurological or hematological abnormalities20. However, it is important to emphasize that food supplements should only be used in cases in which supplementation is recommended (e.g. B12 supplementation recommended for vegans) and not as a general substitute for a healthy diet; it is advisable to consult a healthcare professional (e.g., a dietitian) and to make sure not to exceed the recommended dosage21. Users should be aware, that supplements can cause potential harm such as adverse reactions, drug interactions, monetary cost, delay of more effective therapy, false hope, and an increased medication burden22.

To date, there is a lack of knowledge about the health and supplementation behavior of Austrian vegans. This study aimed to investigate health and supplementation behavior, with special emphasis on the supplementation of B12, and to demographically characterize the community of Austrian adult vegans.

Methods

Respondents and survey administration

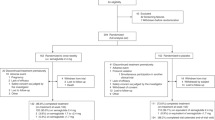

A nonrandom, voluntary sample of adult vegans with a principal residence in Austria was recruited with an online cross-sectional survey. The eligibility criteria for participation in the survey were (1) principal residence in Austria, (2) a current vegan diet, (3) age over 18 years, and (4) willingness to voluntarily participate in the survey. These criteria were queried at the beginning of the survey, and respondents who clicked the survey link but were not eligible were taken directly to the end of the survey. The online survey was created with the EFS Survey version 21.2 software (Tivian XI GmbH, Cologne, Germany). The online survey link was provided to Austrian vegan community groups, forums, and accounts via the social media and messenger platforms Instagram, Facebook, and WhatsApp. No compensation or incentives were offered for participation.

The survey included a total of 23 questions. The question regarding age (years) was asked in an open-ended response format, and gender was operationalized according to recommendations to address diversity23. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated (kg/m2) from self-reported body weight (kg) and height (cm). Respondents with a BMI of at least 30 were classified as obese. The International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) 2011 was used for the operationalization of educational levels, and respondents with an ISCED level of at least 6 (i.e., bachelor’s degree) were classified as “academically educated”. Self-rated general health was queried as in the Austrian wave of the European Health Interview Survey24. The survey tracked the proportion of respondents who currently resided in the capital Vienna. With a population of approximately 1.9 million, Vienna is by far the country's largest city, while the next largest cities have fewer than 300,000 inhabitants. Items on supplementation behavior were used as in an online survey on the use of supplements and fortified foods among German vegans conducted in 20162. The outcomes “B12 supplementation”, “vit B complex supplementation”, “multivitamin supplementation”, and “B12 fortified foods” were combined into an outcome expressing whether any B12 was consumed through supplements and/or fortified foods. To our knowledge, these items have not been tested for reliability or validity. Our survey, before being applied in this study, underwent face validity pretesting in a sample of ten individuals who provided feedback on the understandability, functionality, content, and completion time. Participation in the survey was anonymous and voluntary and could be terminated at any time without justification. The questionnaire was online for a period of 2 months from January until March 2022. There was no randomization or alternation of items, as later questionnaire sections built on responses and information given in the earlier sections. All items included a nonresponse option “don’t know/prefer not to say”. Respondents had the option to save and continue later, as well as to change their answers using the "Back" button. Duplicate participation by the same respondent was avoided by the use of cookies. Responses were stored in the online survey system after the last page of the survey was completed. At the time of conducting this research, anonymous surveys did not require formal review by a research ethics committee under Austrian research governance, in which the Declaration of Helsinki defines applicability to research on identifiable human data25. The survey followed ethical research practices (i.e., voluntary participation; reassurance of anonymity, data protection, and confidentiality; advance information on purpose and content; provision of contact details of the research team; and full disclosure of involved organizations). This information was summarized on the first page of the online survey. Anonymous electronic consent to voluntary participate was required to begin the survey, but no signatures were obtained. Reporting follows the Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS)26.

Statistical analysis

Responses were exported to SPSS statistical software version 27 (IBM Corp., 2021 Armonk, NY). Kolmogorov‒Smirnov tests and examination of quantile‒quantile plots were performed to assess the normality of metric data. Descriptive data are presented as medians with interquartile ranges (due to the violated normality assumption) or as frequencies with percentages. Subgroup analysis examined associations between respondent characteristics and health/supplementation behaviors by cross-tabulation. Twenty-one outcome items on health and supplementation behavior (as shown in Tables 1, 2, 3) were thereby compared in three dichotomous subgroup analyses by gender (male/female), completed academic education (yes/no), and ever taken professional nutritional advice by a dietitian or nutritionist (yes/no), giving a total of 63 statistical tests. Otherwise, no adjustments for confounders or sensitivity analyses were applied. These association analyses were prespecified but not based on a prospective sample size calculation. Because of the online survey design, a larger sample size did not cause any additional effort or cost. Thus, a sample size that was as large as possible was aimed for. A larger sample size implies that smaller effects reach statistical significance. The observed effects were therefore interpreted carefully with a focus on their effect sizes (comparison of percentages and φ). Due to a lack of knowledge about the distribution of participant characteristics in the vegan population, no adjustments for nonrepresentative samples, such as weighting of items, were made in the analysis. Exact chi-squared-based p values were reported, rounded to three decimal places. The multiplicity of testing (63 tests applied to the sample, with alpha 0.05) was corrected by the Bonferroni method, with a p value < 0.0008 consequently indicating statistical significance.

Results

Respondents

Approximately 2% of Austrian adults (i.e., approximately 145,000 individuals) follow a vegan diet1 and were therefore potentially eligible to participate. The link to the online survey was accessed by 2373 individuals, of whom 2027 began the survey after reading the introductory information. After verifying eligibility based on questions about age, vegan diet, and principal residence in Austria, 1784 individuals remained in the sample. Of these 1784 individuals, 1565 completed a valid questionnaire, resulting in a completion rate of 87.7%. Invalid data points include missing and implausible values (e.g., body weight of 851 kg, height of 58 cm), whereas the “don’t know/prefer not to say” selections were processed and reported in the analysis.

Survey respondents were fairly young (median 29 years), although up to 74 years of age and predominantly female (86%), and current residence in the federal capital Vienna was strongly overrepresented. Nearly half of the respondents (49%) had completed an academic education at a bachelor’s level or higher, compared to 13% in the general adult population27. Only 6% of the sample was obese, compared to 17% in the general adult population28. BMI was below 18.5 kg/m2 among 101 (7%) of the respondents. Although recommended for vegans by the German Nutrition Society9, only 9% of the respondents had already taken professional nutritional advice. In summary, Austrian vegans can be characterized as predominantly young, female, urban, highly educated, and nonobese (Table 1).

Health and supplementation behavior

General health status was self-rated as “very good” or “good” by 90.0% of the respondents, and 76.7% self-rated their dietary behavior as “healthy” or “somewhat healthy”. Regular participation in sports (i.e., at least three times a week) was reported by 62.2% of respondents. Regular alcohol consumption (i.e., at least several times a week) was reported by 6.4%, and 12.9% reported daily smoking. B12 status was checked at least once a year by 75.6% of respondents. Sixteen percent said they did not undergo any micronutrient status assessment, and another 22.2% did so less frequently than once a year. B12 supplements were taken by 82.2%, and 92.1% had any B12 intake through supplements and/or fortified foods. Other supplements that respondents took were: vit D (79.6%), omega-3 (50.8%), iron (49.5%), zinc (41.3%), protein (36.4%), calcium (35.8%), selenium (32.4%), vit B complex (31.7%), multivitamin (31.6%), iodine (29.1%), vit B2 (24.7%), and others (15.7%). Eight percent reported never taking nutritional supplements. Thus, the prevalence of supplement use was generally high and higher for individual components than for combined products.

The prevalence of “very good” or “good” general health was fairly similar among male (88.2%) and female (90.5%) respondents. This prevalence was lower in the general adult population (75%) but correspondingly similar across genders24. The prevalence of regular drinking (at least several times a week) was higher among male vegans than among female vegans (10.8% and 5.8%, respectively, p = 0.009) but markedly lower than in the general adult population (52% and 28%, respectively)24. The prevalence of daily smoking was similar among male (12.9%) and female (13.1%) respondents. In contrast, in the general adult population, this prevalence is higher among men (24 ß%) than among women (18%)24. Statistically significant differences in health and supplementation behaviors between genders were found for healthy eating behavior, regular drinking, checking B12 status, B12 supplementation, and iron supplementation with women showing more favorable behavior for all parameters; notably, women of childbearing age have an elevated requirement for iron29. The use of other dietary supplements was similar for both genders (Table 2). Due to a small number (n = 4) of respondents of diverse genders, the interpretability of their behaviors was limited. However, three respondents (75%) reported checking their B12 status, and four (100%) consumed B12 through supplements and/or fortified foods.

Academically educated respondents (i.e., ISCED levels 6 to 8), rated their eating, smoking, and sports behaviors significantly better than less educated respondents. The prevalence of B12 and vit D supplementation was slightly higher among academically educated respondents, whereas the use of other supplements was similar (Table 3).

Professional nutritional advice had been taken by only 9.5% of female and 8.4% of male respondents. Those who had received such advice reported a lower smoking prevalence, higher prevalence of checking B12 status, consuming B12 through supplements and/or foods as well as taking omega-3, selenium, and iodine supplements. Only 3.4% of those who took professional nutritional advice, did not consume B12 through supplements and/or fortified foods, and 11.6% did not have their B12 status checked (Table 4).

Discussion

This study provides novel insights into the health and supplementation behaviors as well as demographic characteristics of Austrian adult vegans. As in our study, in which vegans were predominantly female and young, vegetarianism was found to be three times more common among young adults in the U.S. (18–34 years) than among people over 65 years of age30. The share of female vegans (86%) and academically educated vegans (49%) in our study was roughly similar to data from a recent Swiss survey: 83% female, and 54% academically educated31. Self-rated health status and health behavior were markedly better in vegans than among the general Austrian adult population. Within the population of Austrian vegans, beneficial health behaviors and adherence to recommended checkups and supplementation of B12 were more prevalent among those respondents who were female, academically educated, and those who had taken nutritional advice. In contrast, general health status was not associated with these respondent characteristics. The prevalence of supplement use was generally high and higher for individual components than for combined products. The most frequently taken supplements were B12 (82%), vit D (80%), omega-3 (51%), and iron (50%). B12 supplementation was similarly assessed for German vegans (82%)2 and Czech children (86%)32. In a survey of healthcare professionals who were physically present at an international conference on plant-based nutrition, 98% of vegans self-reported supplementing B1233. Within our sample, 92% consumed B12 through supplements and/or fortified foods, and 76% had their B12 status checked at least once a year.

Limitations

This study recruited a nonrandom voluntary response sample via social media and messenger platforms, which introduces a risk of selection bias and limits the generalizability of the findings. The recruitment channels might have better reached younger recipients and those who frequently use social media. Since the distribution of demographic characteristics in the vegan population is not known, representativeness cannot be assessed by matching the sample to the population. Pregnancy or breastfeeding was not assessed or screened out. While most questions asked about usual behaviors, the questions on supplementation were on the current situation and might therefore have been biased by pregnancy or breastfeeding-related supplementation behaviors. Comparisons with other study results were limited by varying survey dates and methodologies.

Implications for future research

To obtain comparable data on the supplementation behaviors of vegans, standardized cross-national assessments are needed. Some societies do not recommend vegan diets for pregnant or breastfeeding women, babies, children, and adolescents, due to uncertainty in research data. Existing evidence suggests that the health of people who follow plant-based diets appears to be generally good, with several advantages but also some risks (hemorrhagic stroke, bone fracture)14. The extent to which these risks can be mitigated in certain populations (particularly children and pregnant or lactating women) by optimal food choices, fortification, and supplementation remains subject to future research.

Conclusions

Austrian vegans can be characterized as predominantly young, female, urban, highly educated, and nonobese. The rate of B12 intake through supplements and/or fortified foods is fairly high (92%) but should be further improved. Further improvement could be achieved by increasing the share of vegans who follow nutritional advice from health care professionals (requiring a diploma in dietetics, nutritional science, or medicine in Austria), and these professionals should put emphasis on recommending B12 intake through supplements and/or fortified foods and B12 status checks.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- EFSA:

-

European Food Safety Authority

- FAO:

-

Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- ISCED:

-

International Standard Classification of Education

- MDN:

-

Median

- NDA:

-

EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies

- vit:

-

Vitamin

- U.S.:

-

United States

References

Statista. Vegetarismus und Veganismus in Österreich. https://de.statista.com/themen/3804/vegetarismus-und-veganismus-in-oesterreich/#dossierKeyfigures. Accessed 30 Aug 2022.

Vollmer, I., Keller, M. & Kroke, A. Vegan diet: Utilization of dietary supplements and fortified foods. An internet-based survey. Ernahrungs Umschau 1, 144–153 (2018).

Stahler C. How many adults in the U.S. are vegan? How many adults eat vegetarian when eating out?. www.vrg.org/journal/vj2020issue4/2020_issue4_poll_results.php. Accessed 27 July 2022.

Ploll, U., Petritz, H. & Stern, T. A social innovation perspective on dietary transitions: Diffusion of vegetarianism and veganism in Austria. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 36, 164–176 (2020).

Elmadfa, I., Freisling, H., Nowak, V. et al. (eds) Österreichischer Ernährungsbericht 2008 (Bundesministerium für Gesundheit, 2009).

FAOSTAT. Food Balance 2010. www.fao.org/faostat. Accessed 28 July 2022.

Melina, V., Craig, W. & Levin, S. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: Vegetarian diets. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 116, 1970–1980 (2016).

Richter, M. et al. Vegane Ernährung Position der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Ernährung eV (DGE) (Utb GmbH, 2016).

Richter, M. et al. Update to the position of the German Nutrition Society on vegan diets in population groups with special nutritional requirements. Ernahrungs Umschau 2, 64–72 (2020).

Rudloff, S. et al. Vegetarian diets in childhood and adolescence: Position paper of the nutrition committee, German Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Medicine (DGKJ). Mol. Cell Pediatr. 6, 4 (2019).

Redecillas-Ferreiro, S., Moráis-López, A. & ManuelMoreno-Villares, J. Position paper on vegetarian diets in infants and children. Committee on Nutrition and Breastfeeding of the Spanish Paediatric Association. Anal. Pediatr. (English Ed.) 92, 306.e1-306.e6 (2020).

Craig, W. J. & Mangels, A. R. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Vegetarian diets. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 109, 1266–1282 (2009).

Neufingerl, N. & Eilander, A. Nutrient intake and status in adults consuming plant-based diets compared to meat-eaters: A systematic review. Nutrients 2, 14 (2021).

Key, T. J., Papier, K. & Tong, T. Y. N. Plant-based diets and long-term health: Findings from the EPIC-Oxford study. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 81, 190–198 (2022).

Pawlak, R. et al. How prevalent is vitamin B(12) deficiency among vegetarians?. Nutr. Rev. 71, 110–117 (2013).

EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products Nutrition, and Allergies. Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for cobalamin (vitamin B12). EFS2 25, 13 (2015).

Pawlak, R. To vegan or not to vegan when pregnant, lactating or feeding young children. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 71, 1259–1262 (2017).

Watanabe, F. & Bito, T. Vitamin B12 sources and microbial interaction. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 243, 148–158 (2018).

Rizzo, G. et al. Vitamin B12 among vegetarians: Status, assessment and supplementation. Nutrients 25, 8 (2016).

Shipton, M. J. & Thachil, J. Vitamin B12 deficiency—a 21st century perspective. Clin. Med. (Lond.) 15, 145–150 (2015).

British Nutrition Foundation. Food supplements factsheet. https://archive.nutrition.org.uk/attachments/article/1259/BNF%20Food%20supplements%20factsheet.pdf. Accessed 28 July 2022.

Moses, G. The safety of commonly used vitamins and minerals. Aust. Prescr. 44, 119–123 (2021).

Döring, N., Bortz, J. & Pöschl, S. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften (Springer, 2016).

STATISTIK AUSTRIA. Österreichische Gesundheitsbefragung 2019. Hauptergebnisse des Austrian Health Interview Survey (ATHIS) und Methodische Dokumentation (Wien, 2020).

World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310, 2191–2194 (2013).

Sharma, A. et al. A consensus-based checklist for reporting of survey studies (CROSS). J. Gen. Intern. Med. 36, 3179–3187 (2021).

STATISTIK AUSTRIA. Bildungsstand (ISCED 2011) der Bevölkerung ab 15 Jahren Bildungsstand der Bevölkerung ab 15 Jahren 2019 nach Altersgruppen und Geschlecht. Bildungsstandregister 2019. https://www.statistik.at/statistiken/bevoelkerung-und-soziales/bildung/bildungsstand-der-bevoelkerung. Accessed 28 July 2022.

Eurostat. Body mass index (BMI) by sex, age and income quintile. Third wave of EHIS conducted in 2019, data collection period 2018–2020 for Austria.

EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products Nutrition, and Allergies. Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for iron. EFS2 13, 4254 (2015).

Stahler C. How often do Americans eat vegetarian meals? And how many adults in the US are vegetarian? The Vegetarian Resource Group website. http://www.vrg.org/nutshell/Polls/2016_adults_veg.htm. Accessed 27 July 2022.

Swissveg. Anzahl VeganerInnen und VegetarierInnen 2021. https://www.swissveg.ch/2021_10_Anzahl_Veganer_Vegetarier?language=de. Accessed 28 July 2022.

Světnička, M. et al. Cross-sectional study of the prevalence of cobalamin deficiency and vitamin B12 supplementation habits among vegetarian and vegan children in the Czech Republic. Nutrients 25, 14 (2022).

Jeitler, M. et al. Knowledge, attitudes and application of critical nutrient supplementation in vegan diets among healthcare professionals-survey results from a medical congress on plant-based nutrition. Foods 25, 11 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all vegans who voluntarily participated in the survey and acknowledge the support of Clemens Reindl in setting up the online survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.F. and P.P. designed the study and developed the survey, analyzed, and interpreted the data. M.F. wrote a bachelor’s thesis in Dietetics at FH Campus Wien University of Applied Sciences based on which P.P. prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript".

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fuschlberger, M., Putz, P. Vitamin B12 supplementation and health behavior of Austrian vegans: a cross-sectional online survey. Sci Rep 13, 3983 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30843-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30843-1

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.