Abstract

Hypertension is a public health issue touted as a “silent killer” worldwide. The present study aimed to explore the sex differential in the association of anthropometric measures including body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-hip ratio with hypertension among older adults in India. The study used data from the Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) conducted during 2017–18. The sample contains 15,098 males and 16,366 females aged 60 years and above. Descriptive statistics (percentages) along with bivariate analysis were presented. Multivariable binary logistic regression analyses were used to examine the associations between the outcome variable (hypertension) and putative risk or protective factors. About 33.9% of males and 38.2% of females aged 60 years and above suffered from hypertension. After adjusting for the socioeconomic, demographic and health-behavioral factors, the odds of hypertension were 1.37 times (CI: 1.27–1.47), significantly higher among older adults who were obese or overweight than those with no overweight/obese condition. Older adults with high-risk waist circumference and waist-hip ratio had 1.16 times (CI: 1.08–1.25) and 1.42 times (CI: 1.32–1.51) higher odds of suffering from hypertension, respectively compared to their counterparts with no high-risk waist circumference or waist-hip ratio. The interaction effects showed that older females with overweight/obesity [OR: 0.84; CI: 0.61–0.74], high-risk waist circumference [OR: 0.89; CI: 0.78–0.99], and high-risk waist-hip ratio [OR: 0.90; CI: 0.83–0.97] had a lower chance of suffering from hypertension than their male counterparts with the similar anthropometric status. The findings suggested a larger magnitude of the association between obesity, high-risk waist circumference, high-risk waist-hip ratio and prevalent hypertension among older males than females. The study also highlights the importance of measuring obesity and central adiposity in older individuals and using such measures as screening tools for timely identification of hypertension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension is a public health issue touted as a “silent killer” worldwide. It disproportionately affects the people of low- and middle-income countries with weak healthcare systems1,2. Globally, cardiovascular diseases (CVD) have emerged as the primary cause of death and disability, and the highest burden of CVD is attributable to hypertension3. In 2017, high systolic blood pressure was the leading cause for 10.4 million deaths worldwide4. With the shift in age dimensions worldwide, the threat of increasing cases of chronic conditions hiked, especially among the higher age groups. As a developing country, India is also observing demographic transition with a projected 20% increase in 60 years and above population by 2050. Besides being prevalent among older adults, a substantial sex differential has also been noticed in hypertension. For instance, in India, 3 out of 10 males and 4 out of 10 females were diagnosed with hypertension in 20185. Evidence from the National Family Health Survey 2015–16 showed a higher prevalence of hypertension among men; however, at the age of 40 years and above, females were at higher risk than their male counterparts6.

Globally, various behavioural, socioeconomic, demographic and genetic factors have been linked with the occurrence of hypertension1. In the Indian scenario, existing literature had identified increasing age, obesity, smoking, diabetes and extra salt intake as common risk factors of hypertension7,8,9. Several studies have provided evidence on the mechanisms of obesity-induced hypertension10,11,12. Being a behavioural risk factor of hypertension, obesity has seen a threefold increase since 197513. In India, 29% and 38% of obese male and female between 15 and 49 years were hypertensive14. Subsequently, one study based on the Indian city of Mangalore also showed that obese adults aged 20 years and above were three times more likely to experience hypertension. In the Indian context, several systematic reviews have concluded that obese adults have a greater risk of being hypertensive7,8,15. A series of cross-sectional studies (1995–2015) in the Indian city of Jaipur had concluded that obesity measured in terms of increased Body mass index (BMI), waist-circumference and waist-hip ratio was significantly associated with the increasing risk of hypertension among older adults16,17. BMI is the most popular anthropometric indicator for measuring obesity among adults. Extant research has also used waist-circumference, hip circumference and waist-hip ratio as measures of central-obesity, which have systematic advantages over BMI18. A primary study covering the slums of the Indian city of Tirupati had reported that higher BMI increased the risk of self-reported hypertension among adults aged between 20 and 70 years19. One study covering adults aged 20 years and above from Jabalpur city showed that high BMI, waist-circumference and waist-hip ratio was associated with pre-hypertension and hypertension level blood pressure20. However, with the higher rates of chronic diseases and differences in adiposity measures among older adults of India, the present study focuses on the 60 years and above males and females who are highly vulnerable.

Owing to the literature, the present study aims to analyze the sex disparity in the relationship of anthropometric indices like BMI, waist circumference and waist-hip ratio with measured Hypertension among Indian older adults. The rationale of such analyses is as follows: First, even though there is ample evidence concerning the association of obesity and Hypertension among Indian adults, most of the findings are not nationally representative. A nationally representative data can provide an idea for other developing nations with the same epidemiological transition level as India. Thus, the present study can be used to reduce the knowledge gap in other developing countries. Second, although we know the prevalence of hypertension differs across sex in various age groups, the sex disparity in the association of anthropometric indices and hypertension is still left unexplored. It would be an exciting finding to explore the wide sex disparity of hypertension across age and the changes in the anthropometric measures among older males and females together affects this association. Although inequality in the prevalence of hypertension or in the association of hypertension with adiposity measures exists for other spheres too like urban–rural, rich–poor, the differences between the male and female sex persist in every age group and may increase with increasing age. Moreover, with the biological differences across the life course can immensely differentiate the association among males and females. For example, reproductive changes in the life of females, changes in lifestyle and alteration in physical work after retirement. Third, there is an incremental disparity between self-reported and diagnosed hypertension prevalence21. The prevalence of self-reported disease status in India has often been significantly understated than the actual disease burden22. Moreover, the recently concluded, nationally representative, Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) wave-I report stated that one in every five Indians aged 60 years and above were unaware of hypertension5. Utilizing the data from baseline wave of LASI, the present study provides an opportunity to look into the measured hypertension prevalence among older Indian adults. Further, we examined the sex difference in the relationship between obesity-related measures and hypertension among older adults in India.

Methods

Data source

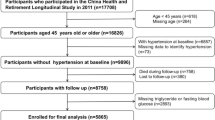

The present study used data from the LASI’s baseline wave, conducted during 2017–18. The survey is a joint undertaking of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, the International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), and the University of Southern California (USC)5. This nationally-representative longitudinal survey collected vital information on the physical, social, and cognitive well-being of India’s older adults, and is proposed to be followed up for 25 years. The data of over 72,000 individuals aged 45 and above and their spouses (irrespective of age) were collected from all states and union territories of India. The sample is based on a multistage stratified cluster sample design, including three and four distinct rural and urban area selection stages, respectively. The survey provides scientific insights and facilitates a harmonized design which helps in comparing with parallel international studies. Further, the details of sample design, survey instruments, fieldwork, data collection and processing, and response rates are publicly available in the LASI report available on the website Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI)5.

We used the data of 15,098 males and 16,366 females aged 60 years and above in India. Further, sample of those with overweight/obesity, high-risk waist circumference and waist-hip ratio may differ from the total sample as every older individual did not give consent for the measurements5. All the methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Outcome variable

The outcome variable was measured hypertension among older adults. Blood pressure was measured among the respondents after their consent (signed/oral). Omron HEM-7121 blood pressure monitors were used to measure the blood pressure of participants. To obtain accurate results participants were asked to avoid exercise, smoking, consuming alcohol or food within 30 min prior to the measurement and no wounds or swell in the area of measurement5. Three blood pressure measures were taken with a gap of 1 min for each in the relax position. The average of the last two readings were considered for the statistical analysis. Hypertension is defined as when an individual had systolic blood pressure of more than equals to 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure of more than equals to 90 mmHg23. Therefore, the variable was coded in binary form i.e., hypertension (no/yes).

All the data were collected by the trained investigators after completing their training on methods and process of study. A detailed instruction is also provided to them regarding taking blood pressure, anthropometric measurements and biological specimen collection.

Explanatory variables

The explanatory variables for the present study were taken into consideration after an extensive literature review. The main explanatory variables were overweight/obesity condition, high-risk waist circumference and high-risk waist-hip ratio of older adults. These body measurements were taken by the trained professionals under standardized protocols. Participants were asked to stand straight against a wall with bare foot onto the base of stadiometer to measure the height. Weight was measured using weighing scale with the participants wearing light clothes without footwear. BMI was calculated by dividing the weight (in kilograms) by the square of height (in m). The respondents having a BMI of 25 and above were categorized as obese/overweight24 coded as “yes”, else “no”.

Participant’s waist and hip circumference was measured using a soft measuring tape called gulik tape in standing position with light clothing5. High-risk waist circumference was coded as no and yes. Males and females who have waist circumferences of more than 102 cm and 88 cm respectively were considered as having high-risk waist circumference25. Further, the high-risk waist-hip ratio was coded as no and yes. Males and females who have a waist-hip ratio of more than equal to 0.90 and 0.85 respectively were considered as having a high-risk waist-hip ratio25.

Further, age was grouped into young old (60–69 years), old–old (70–79 years), and oldest-old (80+ years). Education was coded as no education/primary schooling not completed, primary completed, secondary completed, and higher and above. Marital status was coded as currently married, widowed, and others (separated/never married/divorced). Working status was coded as working, retired, and not working. Tobacco and alcohol consumption was coded as no and yes. Physical activity status was coded as frequent (every day), rare (more than once a week, once a week, one to three times in a month), and never26. And the family history of hypertension was coded as “no” or “yes”.

The monthly per capita expenditure (MPCE) quintile was assessed using household consumption data. The details of the measure are published elsewhere5. The variable was divided into five quintiles i.e., from poorest to richest. Religion was coded as Hindu, Muslim, Christian, and Others. Caste was recoded as Scheduled Tribes, Scheduled Castes, Other Backward Classes, and others. The Scheduled Castes include a group of the population that is socially segregated and financially/economically by their low status as per Hindu caste hierarchy. The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are among the most disadvantaged socioeconomic groups in India. The Other Backward Classes are considered low in the traditional caste hierarchy, but include the intermediate socioeconomic groups. The “others” caste category is identified as those having higher social status. Place of residence was coded as rural and urban. The region was coded as North, Central, East, Northeast, West, and South.

Statistical analysis

We reported descriptive statistics (percentage) along with the estimates from bivariate analysis. Additionally, we used binary logistic regression analysis27 to examine the association between the outcome variable (hypertension) and putative risk or protective factors. The multivariable analysis had four models to explain the adjusted estimates. Model-1 provides the adjusted estimates for the explanatory variables. Model-2, model-3, and model-4 provide the interaction effects28,29 of anthropometric measures of obesity and sex on hypertension among older adults. STATA 14 was used to analyze the dataset. Model-1 represents the adjusted odds ratio for all background characteristics; model-2, 3 and 4 were adjusted for all the background characteristics and represent the interaction effects30.

An "interaction variable" is a variable that is created from an initial set of variables to either fully or partially describe the interaction that is present. In exploratory statistical analyses, it is typical to employ original variable products as the foundation for assessing the presence of interaction, with the option of later adding other more realistic interaction variables. Multiple interaction variables are constructed when there are more than two explanatory variables, with pairwise-products indicating pairwise interactions and higher order products representing higher order interactions.

Thus, for a response Y and two variables x1 and x2 an additive model would be:

In contrast to this,

where Y is dependent variable (various Hypertension) and α is intercept, x1 is individual level independent variable, x2 is individual level independent variable, xa is alcohol users, xs is smokers, (β3 xs * xa ) is the interaction of sex and obesity related indicators and ε0 is error. Models lacking the interaction term d (x1 * x2) are frequently presented, although this confuses the main effect and interaction effect (i.e., without specifying the interaction term, it is possible that any main effect found is actually due to an interaction).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data is freely available in the public domain and survey agencies that conducted the field survey for the data and biomarker collection have collected informed consent "oral consent or signed consent" from the respondents. The study was approved by the Health Ministry’s Screening Committee, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), and the Institutional Review Boards at IIPS and its collaborating institutions. The survey ensured international ethical standards of confidentiality, anonymity, and informed consent.

Results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of 15,098 males and 16,366 females aged 60 years and above in India. Nearly half of the older participants belonged to the 60–69 age category (58% male and 59% female). About 53% of males and 81% of females were illiterate or not completed primary education. The proportion of currently married males (81%) was higher than that of females (44%). Moreover, 18% and 26% of males and females were found overweight/obesity. High-risk waist circumference was observed among 9% males and 37% females. Furthermore, 75% of males and 78% of females had a high-risk waist-hip ratio. Approximately 44% of overweight/obese older adults had hypertension. About, 47% of males and 43% of females with high-risk waist circumference suffered from hypertension. In contrast, 37% of males and 40% of females with a high waist-hip ratio suffered from hypertension. Hypertension is significantly higher among the oldest-old males and females. Widowed males (37%) and females (41.3%) had a higher chance of suffering from hypertension than their married counterparts. Retired males and females had a higher chance of suffering from hypertension than those currently working. Older males and females who never involved in physical activity suffered from hypertension. Besides, 39% of males and females who lived in urban areas were suffering from hypertension. In terms of region, older adults residing in the northeast region had a higher prevalence of hypertension.

Table 2 presents the multivariable association of hypertension with the explanatory variables among older adults in India. Model 1 shows that the odds of hypertension were 1.37 times (CI: 1.27–1.47), significantly higher among older adults who were obese or overweight compared to those with no overweight/obese condition. Older adults with high-risk waist circumference and waist-hip ratio had 1.16 times (CI: 1.08–1.25) and 1.42 times (CI: 1.32–1.51) higher odds of suffering from hypertension, respectively compared to their counterparts with no high-risk waist circumference or waist-hip ratio. The odds of hypertension were 1.20 times (CI: 1.10–1.31) higher among oldest-old than those who belonged to the young-old age category; 1.31 times (CI: 1.26–1.42) higher among widowed than those who were currently married; 1.14 times (CI: 1.06–1.24) higher among older adults who completed secondary education compared to those who were illiterate. Alcohol consumption among older adults was associated with 1.23 times (CI: 1.15–1.33) higher odds of suffering from hypertension. Belonging to households with richest MPCE and Other Backward Caste (OBC) was advantageous for older adults in reducing hypertension risk. Further, individuals belonging to the southern region had 1.25 times (CI: 1.15–1.36) higher odds of suffering from hypertension than those who belonged to the northern region.

Model 2, 3, and 4 estimate the adjusted odds ratio after introducing interaction effects. Females who were overweight or obese had lower odds of suffering from hypertension than their overweight/obese male counterparts [OR: 0.84; CI: 0.61–0.74]. Similarly, females who had high-risk waist circumference and waist-hip ratio had lower odds of suffering from hypertension compared to their male counterparts with the similar anthropometric status.

Discussion

Recent studies have observed that hypertension prevalence rates are on the rise in developing countries compared to developed countries with no improvement in awareness or control rates31,32,33. Based on an extensive nationally representative data of the older population in India, we examined BMI, waist-to-hip ratio and waist circumference to assess obesity and investigate their associations with hypertension. The overall 33.9% and 38.2% prevalence of hypertension among older males and females, respectively, indicates that the condition affects a sizable proportion of older Indian adults. The current prevalence estimates are comparable and higher than the pooled estimates among the Indian adults (18 years and above), with 29.8% being hypertensive8. However, in a recent study among multi-ethnic Asian populations, 33.1% Malaysian adults and 31.5% Chinese adults were hypertensive34. Another cross-sectional study in Indonesia found 31.0% of males and 35.4% of females having hypertension35.

Consistent with past studies, hypertension among the study sample was associated with their BMI, waist-to-hip ratio and waist circumference36,37,38,39,40. Several population-based studies have compared such anthropometric indicators with incident hypertension, and there are inconsistencies in the findings41,42,43. Some studies have specifically shown waist circumference to have an independent effect on the risk of hypertension and claimed that it could replace waist-to-hip ratio and BMI as a simple indicator for weight management44,45,46. A large community-based cross-sectional study in India reported the prevalence of isolated systolic hypertension as 2.8% among patients with normal BMI and 21.1% among those with a higher BMI47. Similarly, multiple studies have shown an increased prevalence of hypertension in people with adverse obesity-related measures48,49,50.

The prevalence of hypertension increased with age in males and females, also observed in the previous population-based studies51,52,53. The current findings further showed that older adults retired from work had increased odds of hypertension compared to their currently working counterparts. For aged people, especially the “oldest-old”, the “healthy worker effect” (survival bias) may exist54, where the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases might have caused retirement of individuals, thus leading to the inverse causality in the observed association. Although the regression results showed no statistical significance, the urban–rural gradient observed in the bivariate analysis is similar to previous findings from India that showed that the prevalence is higher in urban areas among males and females8,55. This urban–rural differential has reversed in many high- income countries where hypertension is more in the rural populations56. Thus, the current result shows that the changes influencing the reversal of concentration of hypertensive people in urban areas have not yet happened in India. However, the finding of a recent study suggested an urban–rural convergence of hypertension in India that is taking place due to a rapid urbanization with consequent changes in lifestyles and the resultant increase in overweight and obesity57.

Further, the significant positive association of alcohol consumption with prevalence of hypertension among older adults are consistent with several studies in different parts of the world that demonstrated the negative effects of higher levels of frequent drinking on cardiovascular health58,59,60. A recent study also established the causal pathway between moderate-to-heavy alcohol drinking and prevalence of hypertension61. The current study also found a higher percent of older males reporting tobacco use than older females which is parallel with other studies in India showing higher rates of tobacco use in males and those from lower socioeconomic groups62,63, however, the multivariate analysis showed no significant association of tobacco use with hypertension. Future studies may focus on this aspect. Also, the finding that showed a higher prevalence of hypertension among people who are disadvantaged in many of the socioeconomic indicators such as household per capita expenditure and marital status was in accordance with previous studies in India64. This reflects the changes in morbidity dynamics in Indian context since the burden of chronic diseases including hypertension begins to shift from higher to lower socioeconomic groups in the later stages of the epidemiological transition65,66.

Another important finding of the present study was the significant association of Muslim and other religious groups with higher prevalence of hypertension. The finding is in concordance with prior research showing the protective role of religion and religious behaviors on high blood pressure67,68. This suggests the need for a comprehensive evaluation of the role of specific religions in hypertension control. The analysis of regional variations in the prevalence rates also concurs with earlier studies that have shown a high prevalence of hypertension in South India7,69,70. The high prevalence of hypertension in South India maybe attributed to the higher presence of cardio-metabolic risk factors such as high BMI and central obesity in this region8,71.

It is reported that frequently used anthropometric indices in epidemiological studies such as BMI, waist circumference and waist-hip ratio, measure body fat with different results across sex and in different populations due to genetic and lifestyle differences72, which makes a comparison between studies difficult. The increased high-risk waist-circumference among older females than males in the current study is also in line with previous research reporting an accelerated shift toward a more central fat distribution in females after menopause while males have a centrally located fat distribution during adulthood73,74, resulting in increased risk of hypertension in old age females. While we have shown the prevalence of hypertension across various factors such as obesity-related-measures, alcohol consumption and physical inactivity that were significantly different among older males and females, results suggested that sex is a strong confounder.

The analyses of interactive effects of sex on the observed associations were conducted in order to intuitively show and compare the relationships between obesity measures and hypertension among older males and females. Findings of several clinical and epidemiological studies showing higher rates of hypertension with aging in females versus males, suggest that sex and/or sex hormones have a prominent role in hypertension75,76,77. Such studies showed that sex differences exist in hypertension and post-menopausal females have pronounced increases in hypertension compared to males in the same age groups78,79,80. The current findings in line with previous studies observed the effect of sex on the association of obesity related measures and hypertension suggesting that there are physiological differences among older males and females regarding the distribution of body fat and related cardiovascular health outcomes81,82,83,84. However, whether the sex differential is due to biological factors, inadequate treatment due to physician inertia or adherence, or inappropriate drug choices or sex-related differences in medications, all has to be further investigated.

The strengths of this study include the nationally representative survey with a large sample size. Also, various covariates consisting of separate obesity-related anthropometric measures increase the validity of the study. Nevertheless, cross-sectional design of the study is a major limitation that provides only a one-time measurement of obesity and related indices and hypertension. Hence, it is unfeasible to state any causal inferences from the study. Further, as health literacy, self-monitoring and taking medication would influence blood pressure significantly, not including such variables in the current analysis might lead to misclassification bias, which need to be addressed in future studies with longitudinal design.

Conclusion

All three indicators related to obesity studied here have shown significant association with the prevalence of hypertension suggesting the importance of weight reduction in prevention of hypertension. The findings also suggested the larger magnitude of the association between obesity, high-risk waist circumference, high-risk waist-hip ratio and hypertension among older males than females. The study also highlights the importance of measuring obesity and central adiposity in older individuals and using such measures as screening tool for timely identification of hypertension. Since it carries a higher risk for all-cause, as well as cardiovascular mortality, among modifiable risk factors, hypertension management should be a key health care priority for older population and policies should be developed with a focus on sex differences in related risks.

Data availability

The study uses secondary data which is available on reasonable request through https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/content/lasi-wave-i. The data used in the study can be deposited publicly. The data will also be available on request from the corresponding author.

References

WHO. A global brief on hypertension: silent killer, global public health crisis: World Health Day 2013. World Health Organization 2013.

WHO. Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2018. 2018.

Rg, A. et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 76, 2982–3021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010 (2020).

Stanaway, J. D. et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Stu. The Lancet 392, 1923–1994. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32225-6 (2018).

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), NPHCE, MoHFW HTHCS of PH (HSPH) and the U of SC (USC). Longitudinal Ageing Study in India ( LASI ) Wave 1, 2017–18, India Report. Mumbai: 2020.

Kumar, K. & Misra, S. Sex differences in prevalence and risk factors of hypertension in India: Evidence from the National Family Health Survey-4. PLoS ONE 16, e0247956. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247956 (2021).

Devi, P. et al. Prevalence, risk factors and awareness of hypertension in India : A systematic review. J. Hum. Hypertens. https://doi.org/10.1038/jhh.2012.33 (2013).

Anchala, R. et al. Hypertension in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence, awareness, and control of hypertension. J. Hypertens. 32, 1170 (2014).

Shah, S. N. et al. Indian guidelines on hypertension-IV (2019). J. Hum. Hypertens. 34, 745–758. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-020-0349-x (2020).

Rahmouni, K. et al. Obesity-associated hypertension: new insights into mechanisms. Hypertension 45, 9–14 (2005).

Kotsis, V. et al. Mechanisms of obesity-induced hypertension. Hypertens. Res. 33, 386–393. https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2010.9 (2010).

DeMarco, V. G., Aroor, A. R. & Sowers, J. R. The pathophysiology of hypertension in patients with obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 10, 364 (2014).

WHO. World Health Organization obesity and overweight fact sheet. World Health Organization 2016.

IIPS, ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) 2015–16 India. 2017.

Babu, G. R. et al. Association of obesity with hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus in India: A meta-analysis of observational studies. World J. Diabetes 9, 40 (2018).

Gupta, R. & Gupta, V. P. Hypertension epidemiology in India: Lessons from Jaipur heart watch. Curr. Sci. 97, 349–355 (2009).

Gupta, R. et al. 25-Year trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in an Indian urban population: Jaipur Heart Watch. Indian Heart J. 70, 802–807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ihj.2017.11.011 (2018).

Ghesmaty Sangachin, M., Cavuoto, L. A. & Wang, Y. Use of various obesity measurement and classification methods in occupational safety and health research: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Obes. 5, 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40608-018-0205-5 (2018).

Reddy, S. S. & Prabhu, G. R. Prevalence and risk factors of hypertension in adults in an Urban Slum, Tirupati, AP. Indian J. Community Med. 30, 84 (2005).

Bhadoria, A. S. et al. Prevalence of hypertension and associated cardiovascular risk factors in Central India. J. Fam. Community Med. 21, 29 (2014).

Gonçalves, V. S. S. et al. Accuracy of self-reported hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hypertens. 36, 970–978 (2018).

Onur, I. & Velamuri, M. The gap between self-reported and objective measures of disease status in India. PLoS ONE 13, e0202786 (2018).

World Health Organization. Hypertension. 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension (accessed 23 Jun 2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Association between obesity-related anthropometric indices and multimorbidity among older adults in Shandong, China: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036664 (2020).

Anusruti, A. et al. Longitudinal associations of body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio with biomarkers of oxidative stress in older adults: Results of a large cohort study. Obes. Facts https://doi.org/10.1159/000504711 (2020).

Kumar, M., Srivastava, S. & Muhammad, T. Relationship between physical activity and cognitive functioning among older Indian adults. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–13 (2022).

Osborne, J. & King, J. E. Binary logistic regression. In: Best Practices in Quantitative Methods. SAGE Publications, Inc. 2011. 358–84. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412995627.d29

Chauhan, S. et al. Interaction of substance use with physical activity and its effect on depressive symptoms among adolescents. J. Subst. Use https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2020.1851411 (2020).

Muhammad, T., Govindu, M. & Srivastava, S. Relationship between chewing tobacco, smoking, consuming alcohol and cognitive impairment among older adults in India: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 21, 85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02027-x (2021).

Van Der Weele, T. J. & Knol, M. J. A tutorial on interaction. Epidemiol. Methods 3, 33–72. https://doi.org/10.1515/em-2013-0005 (2014).

Ibrahim, M. M. Hypertension in developing countries: A major challenge for the future. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 20, 1–10 (2018).

Mohanty, S. K. et al. Awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in adults aged 45 years and over and their spouses in India: A nationally representative cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 18, e1003740 (2021).

Bhatia, M. et al. Diagnosis and treatment of hypertension among people aged 45 years and over in India: A sub-national analysis of the variation in performance of Indian states. Front. Public Health 9, 1654 (2021).

Liew, S. J. et al. Sociodemographic factors in relation to hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control in a multi-ethnic Asian population: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 9, e025869 (2019).

Peltzer, K. & Pengpid, S. The prevalence and social determinants of hypertension among adults in Indonesia: A cross-sectional population-based national survey. Int. J. Hypertens. 2018.

Gupta, R. et al. High prevalence and low awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in Asian Indian women. J. Hum. Hypertens. 26, 585–593. https://doi.org/10.1038/jhh.2011.79 (2012).

Manimunda, S. P. et al. Association of hypertension with risk factors & hypertension related behaviour among the aboriginal Nicobarese tribe living in Car Nicobar Island, India. Indian J. Med. Res. 133, 287–293 (2011).

Thankappan, K. R. et al. Prevalence, correlates, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in Kumarakom, Kerala: Baseline results of a community-based intervention program. Indian Heart J. 58, 28–33 (2006).

Hazarika, N. C., Biswas, D. & Mahanta, J. Hypertension in the elderly population of Assam. J. Assoc. Phys. India 51, 567–573 (2003).

Lloyd-Sherlock, P. et al. Hypertension among older adults in low-and middle-income countries: Prevalence, awareness and control. Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 116–128 (2014).

Fuchs, F. D. et al. Anthropometrie indices and the incidence of hypertension: A comparative analysis. Obes. Res. 13, 1515–1517. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2005.184 (2005).

Nyamdorj, R. et al. Comparison of body mass index with waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and waist-to-stature ratio as a predictor of hypertension incidence in Mauritius. J. Hypertens. 26, 866–870. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f624b7 (2008).

Taleb, S. et al. Associations between body mass index, waist circumference, waist circumference to-height ratio, and hypertension in an Algerian adult population. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-10122-6 (2020).

Siani, A. et al. The relationship of waist circumference to blood pressure: The Olivetti Heart Study. Am. J. Hypertens. 15, 780–786. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-7061(02)02976-X (2002).

Olinto, M. et al. Waist circumference as a determinant of hypertension and diabetes in Brazilian women: A population-based study. Public Health Nutr. 7, 629–635. https://doi.org/10.1079/phn2003582 (2004).

Lean, M., Han, T. & Morrison, C. Waist circumference as a measure for indicating need for weight management. BMJ 311, 158–161 (1995).

Midha, T. et al. Isolated systolic hypertension and its determinants: A cross-sectional study in the adult population of Lucknow district in North India. Indian J. Community Med. 35, 89 (2010).

Zhang, X. et al. Total and abdominal obesity among rural Chinese women and the association with hypertension. Nutrition 28, 46–52 (2012).

Kawamoto, R. et al. High prevalence of prehypertension is associated with the increased body mass index in community-dwelling Japanese. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 216, 353–361 (2008).

Kim, J. et al. The prevalence and risk factors associated with isolated untreated systolic hypertension in Korea: The Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey 2001. J. Hum. Hypertens. 21, 107–113 (2007).

Zhang, M. et al. Body mass index and waist circumference combined predicts obesity-related hypertension better than either alone in a rural Chinese population. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31935 (2016).

Gu, D. et al. Incidence and predictors of hypertension over 8 years among Chinese men and women. J. Hypertens. 25, 517–523. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e328013e7f4 (2007).

Sun, Z. et al. Ethnic differences in the incidence of hypertension among rural Chinese adults: Results from Liaoning Province. PLoS ONE 9, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086867 (2014).

Massamba, V. K. et al. Assessment of the healthy worker survivor effect in the relationship between psychosocial work-related factors and hypertension. Occup. Environ. Med. 76, 414–421 (2019).

Gupta, R., Gaur, K. & Ram, C. V. Emerging trends in hypertension epidemiology in India. J. Hum. Hypertens. 33, 575–587. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-018-0117-3 (2019).

Chow, C. K. et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in rural and urban communities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 310, 959–968. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.184182 (2013).

Gupta, R. Convergence in urban-rural prevalence of hypertension in India. J. Hum. Hypertens. 30, 79–82. https://doi.org/10.1038/jhh.2015.48 (2016).

O’Keefe, J. H. et al. Alcohol and cardiovascular health: The dose makes the poison or the remedy. Mayo Clinic Proc. 89, 382–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.11.005 (2014).

Puddey, I. B. & Beilin, L. J. Alcohol is bad for blood pressure. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 33, 847–852. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04452.x (2006).

Tumwesigye, N. M. et al. Alcohol consumption, hypertension and obesity: Relationship patterns along different age groups in Uganda. Prev. Med. Rep. 19, 101141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101141 (2020).

Puddey, I. B. et al. Alcohol and hypertension—New insights and lingering controversies. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 21, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-019-0984-1 (2019).

Singh, A., Arora, M., English, D. R., et al. Socioeconomic gradients in different types of tobacco use in India: Evidence from global adult tobacco survey 2009–10. BioMed Res. Int. 2015;2015.

Corsi, D. J. et al. Tobacco use, smoking quit rates, and socioeconomic patterning among men and women: A cross-sectional survey in rural Andhra Pradesh, India. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 21, 1308–1318 (2014).

Moser, K. A. et al. Socio-demographic inequalities in the prevalence, diagnosis and management of hypertension in India: Analysis of nationally-representative survey data. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086043 (2014).

Patel, V. et al. Chronic diseases and injuries in India. The Lancet 377, 413–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61188-9 (2011).

Reddy, K. S. & Yusuf, S. Emerging epidemic of cardiovascular disease in developing countries. Circulation 97, 596–601. https://doi.org/10.1177/095042228900300313 (1998).

Meng, Q. et al. Effect of religion on hypertension in adult Buddhists and residents in China: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–11 (2018).

Meng, Q. et al. Correlation between religion and hypertension. Intern. Emerg. Med. 14, 209–237 (2019).

Kusuma, Y. S., Babu, B. V. & Naidu, J. M. Prevalence of hypertension in some cross-cultural populations of Visakhapatnam district, South India. Ethn. Dis. 14, 250–259 (2004).

Gilberts, E. C. A. M., Arnold, M. J. C. W. J. & Grobbee, D. E. Hypertension and determinants of blood pressure with special reference to socioeconomic status in a rural south Indian community. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 48, 258–261. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.48.3.258 (1994).

Kinra, S., Bowen, L. J., Lyngdoh, T., et al. Sociodemographic patterning of non-communicable disease risk factors in rural India: A cross sectional study. Bmj 2010;341.

Misra, A., Wasir, J. S. & Vikram, N. K. Waist circumference criteria for the diagnosis of abdominal obesity are not applicable uniformly to all populations and ethnic groups. Nutrition 21, 969–976 (2005).

Trémollieres, F. A., Pouilles, J.-M. & Ribot, C. A. Relative influence of age and menopause on total and regional body composition changes in postmenopausal women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 175, 1594–1600 (1996).

Kotani, K. et al. Sexual dimorphism of age-related changes in whole-body fat distribution in the obese. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 18, 207–202 (1994).

Faulkner, J. L. & Belin de Chantemèle, E. J. Sex differences in mechanisms of hypertension associated with obesity. Hypertension 71, 15–21 (2018).

Zimmerman, M. A. & Sullivan, J. C. Hypertension: What’s sex got to do with it?. Physiology 28, 234–244 (2013).

Dubey, R. K. et al. Sex hormones and hypertension. Cardiovasc. Res. 53, 688–708 (2002).

Rana, B. K. et al. Population-based sample reveals gene-gender interactions in blood pressure in white Americans. Hypertension 49, 96–106. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000252029.35106.67 (2007).

Fava, C. et al. Association between Adducin-1 G460W variant and blood pressure in swedes is dependent on interaction with body mass index and gender. Am. J. Hypertens. 20, 981–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjhyper.2007.04.007 (2007).

Wenger, N. K. et al. Hypertension across a woman’s life cycle. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 71, 1797–1813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.033 (2018).

Kanter, R. & Caballero, B. Global gender disparities in obesity: A review. Adv. Nutr. 3, 491–498. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.112.002063 (2012).

Barbosa, A. R. et al. Anthropometric indexes of obesity and hypertension in elderly from Cuba and Barbados. J. Nutr. Health Aging 15, 17–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-011-0007-7 (2011).

Munaretti, D. B. et al. Self-rated hypertension and anthropometric indicators of body fat in elderly. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira (English Edition) 57, 25–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2255-4823(11)70011-x (2011).

Luz, R. H., Barbosa, A. R. & d’Orsi, E. Waist circumference, body mass index and waist-height ratio: Are two indices better than one for identifying hypertension risk in older adults?. Prev. Med. 93, 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.09.024 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai for providing the LASI dataset for undertaking the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the research paper: T.M. and S.S.; analyzed the data: S.S.; Contributed agents/materials/analysis tools: T.M., R.P. and R.R.; Wrote the manuscript: T.M., S.S., R.P. and R.R.; Refined the manuscript: T.M. and S.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Muhammad, T., Paul, R., Rashmi, R. et al. Examining sex disparity in the association of waist circumference, waist-hip ratio and BMI with hypertension among older adults in India. Sci Rep 12, 13117 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17518-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17518-z

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.