Abstract

There were limited data on adipose and serum zinc alpha-2-glycoprotein (ZAG) expression and its association with body composition in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD). This study aimed to quantify adipose and serum ZAG expression and evaluate their association with body composition and its longitudinal change, together with mortality in incident dialysis patients. We performed a single-center prospective cohort study. Patients who were planned for peritoneal dialysis were recruited. ZAG levels were measured from serum sample, subcutaneous and pre-peritoneal fat tissue obtained during peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion. Body composition and functional state were evaluated by bioimpedance spectroscopy and Clinical Frailty Scale respectively at baseline and were repeated 1 year later. Primary outcome was 2-year survival. Secondary outcomes were longitudinal changes of body composition. At baseline, the average adipose and serum ZAG expression was 13.4 ± 130.0-fold and 74.7 ± 20.9 µg/ml respectively. Both adipose and serum ZAG expressions independently predicted adipose tissue mass (ATM) (p = 0.001, p = 0.008, respectively). At 1 year, ATM increased by 3.3 ± 7.4 kg (p < 0.001) while lean tissue mass (LTM) remained similar (p = 0.5). Adipose but not serum ZAG level predicted change in ATM (p = 0.007) and LTM (p = 0.01). Serum ZAG level predicted overall survival (p = 0.005) and risk of infection-related death (p = 0.045) after adjusting for confounders. In conclusion, adipose and serum ZAG levels negatively correlated with adiposity and predicted its longitudinal change of fat and lean tissue mass, whilst serum ZAG predicted survival independent of body mass in advanced CKD patient.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dialysis is one of the promising treatments that can effectively remove toxin, maintain homeostasis, and prolong life expectancy in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD). However, dialysis therapy induces protein loss to the dialysate, excessive calories uptake, inflammation, and catabolism. All these culminate obesity and muscle wasting, which are most apparent at the first year of dialysis initiation1,2,3,4. These longitudinal changes in body composition not only cause metabolic problems, but also affect survival5,6,7,8.

Adipose tissue is one of the largest organs in the body. It functions as the major body energy storage, and secretes a wide range of pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators, also known as adipokines9, which modulate multiple inflammatory pathways and maintain body homeostasis. Zinc alpha-2-glycoprotein (ZAG) is one of the identified adipokines that is highly expressed in blood and adipose tissues from patients with CKD10,11,12. It acts as a lipid mobilizing factor which promotes lipolysis, inhibits lipogenesis, and regulates secretion of other adipokines13,14. Therefore, it is often regarded as one of the key body composition regulators, mediating obesity and wasting. Conflicting results have been reported regarding the linkage between serum ZAG expression and body composition in patients with CKD15,16,17, which supports its intrinsic paracrine and autocrine action that cannot be fully reflected by its circulating level14,18. However, there are by far only very limited data that reported adipose ZAG expression and its clinical relevance in patients with CKD.

The objectives of our study are to quantify the ZAG expression at adipose and serum levels in advanced CKD patients, to explore their association with cross-sectional and longitudinal change of body composition, and to identify its prognostic value.

Materials and methods

Study design

This is a single center prospective cohort study. The study was approved by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong—New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Reference Number CREC-2008.554). All study procedures were in compliant with the Declaration of Helsinki. Consecutive incident adult dialysis patients were recruited from 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2013 prior to peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion at Prince of Wales Hospital. Patients who have active malignancy, on anabolic steroids or corticosteroid therapy, and those who were previously on another modality of renal replacement therapy (e.g., hemodialysis, renal transplant) for more than 3 months were excluded.

Written informed consent was obtained before study enrollment. After enrollment, clinical and laboratory data were obtained by chart review. Comorbidity load was evaluated by the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) and the nutritional state was measured by the comprehensive Malnutrition-Inflammation Score (MIS). All subjects received standard dietary counselling by experienced dietitians at the time of dialysis training. In general, they were advised to have energy intake 25 to 35 kcal/kg/day (depending on body mass index (BMI)), 25–30% of which is fat, and protein 1.0–1.2 g/kg/day.

Body composition and functional state assessment

Basic anthropometric parameters including body weight, BMI (calculated as body weight divided by square of height), waist circumference (measured at mid-point between lowest lateral border of ribs and uppermost border of iliac crest), hip circumference (measured as widest portion of the buttocks), midarm circumference and triceps skinfold thickness were measured at baseline. Overweight, general, and central obesity were defined according to the WHO criteria on BMI and gender-specific median of waist circumference respectively.

Multi-frequency bioimpedance spectroscopy device (Body Composition Monitor [BCM], Fresenius Medical Care, Germany), was used to measure the volume of different body compartments19. Electrodes were attached to one hand and one foot with the patient in a supine position after drainage of dialysate. Extracellular water (ECW), intracellular water (ICW), lean tissue mass (LTM), and adipose tissue mass (ATM) were computed.

Frailty assessment was evaluated by retrospective review on clinical assessment forms and notes, as described previously20. Patients were classified into class 1 to 9 according to the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS)21, and they were diagnosed as frail if they belonged to class 4 to 9.

Anthropometry, body composition and function state assessments were repeated 1 year later.

Specimen collection

1–2 g of subcutaneous and pre-peritoneal adipose tissue samples were obtained during the insertion of peritoneal dialysis (PD) catheter (also known as Tenckhoff catheter) by mini laparotomy. The adipose tissue was then processed immediately and stored at − 80 °C overnight).

Serum samples were collected during the standard peritoneal equilibrium test (PET) session, which were performed around 4 weeks after dialysis catheter insertion, and when patient was stable, without concurrent peritonitis and in euvolemic state. The samples were sent to laboratory for processing immediately or stored in 4 °C overnight after collection.

Detection of ZAG

The methods of RNA extraction have been described previously20. ZAG mRNA expression in the adipose tissue was measured by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-QPCR), using the Applied Biosystems Step One Plus system (Foster City, CA). Commercially available Taqman primers and probes, including 2 unlabeled PCR primers and 1 FAM™ dye labeled TaqMan® MGB probe, were used (all from Applied Biosystems). We used the phosphoglycerate kinase-1 (Applied Biosystems) as the housekeeping gene. Results were analyzed with Sequence Detection Software v2.0 (Applied Biosystems) and the relative quantification method by ∆∆Ct was applied for expression of targets in fold compared to the expression detected in samples from healthy subjects.

Serum ZAG level was measured by the commercially available ELISA kit (Alpha-2 Glycoprotein/Glycoprotein/ZAG/A2GP1 Human ELISA kit, BMS 2201, Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, CA) following the instructions from manufacturer. All assays were performed in duplicate. The detection limit of ZAG is 0.174 ng/ml.

Outcome measures

All subjects were followed for a total of 3 years. The overall clinical management was decided by the attending clinician and was not affected by the study. The primary outcome measure was 2-year all-cause mortality following body composition re-assessment. The secondary outcomes were longitudinal changes of body composition.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS for Windows software version 24 (SPSS Inc., Chicago). Descriptive data were presented as mean ± SD. Baseline clinical parameters were compared by Student’s t-test, chi-square test, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), while the correlation was analyzed by Pearson and Spearman’s rank correlation as appropriate. The baseline and longitudinal change in body composition were compared among ZAG expression divided into tertiles. Multivariate linear regression models were then constructed to identify significant predictor of baseline and longitudinal change in body composition parameters. Kaplan Meier plots on ZAG expression in tertiles (low expression: 37.8–62.6 µg/ml; medium expression: 63.0–82.8 µg/ml; high expression: 83.0–149.1 µg/ml) were constructed and compared by log-rank test. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were constructed to further identify independent predictors of survival after adjustment of known potential confounders. The final p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All probabilities were two-tailed.

Results

Patient characteristics

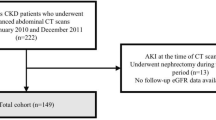

148 incident dialysis patients were enrolled (Fig. 1). Their baseline clinical characteristics, and ZAG expression are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 58.4 ± 11.3 years, and 111 (75%) were male. Serum ZAG level correlated with age (r = − 0.231, p = 0.006) and serum albumin (r = 0.27, p = 0.001), while adipose ZAG correlated with serum urea (r = 0.178, p = 0.03), residual renal function (r = − 0.233, p = 0.008) and serum lipids profile including total cholesterol (r = 0.175, p = 0.038), triglycerides (r = − 0.326, p < 0.001), high-density lipoprotein (r = 0.393, p < 0.001) and low-density lipoprotein (r = 0.177, p = 0.035). Their subsequent dialysis therapy including modality, dialysis adequacy and dialysate dextrose load were comparable between high and low adipose ZAG expression (Table 2).

There was no internal correlation between serum and adipose ZAG expressions (p = 0.1). There was also absence of significant correlation between serum ZAG and the product of adipose ZAG and all adiposity parameters including BMI (p = 1.0), waist circumference (p = 0.9), and ATM (p = 0.5).

Baseline body composition

The baseline anthropometric and body composition parameters are summarized in Table 3. Adipose ZAG correlated with all body composition parameters, whereas serum ZAG correlated with waist, midarm circumference and ATM only (Supplementary Table 1). 13% and 24.5% were general and central obese respectively. BMI, waist circumference and ATM, but not lean tissue mass (LTM), significantly reduced in a stepwise manner along adipose and serum ZAG expressions (Fig. 2). In multivariate linear regression analysis, both adipose (unstandardized B: − 2.093, p = 0.001) and serum ZAG expressions (unstandardized B − 0.201, p = 0.008) predicted baseline ATM independently after adjustment for confounders including age, serum albumin, residual kidney function and MIS score.

Longitudinal change in anthropometry

With time, 11 (7.4%) patients died, 6 (4.1%) patients underwent renal transplantation, 9 (6.1%) patients were switched to hemodialysis, and 5 (3.4%) patients were transferred to other centers (Fig. 1). 117 patients underwent follow-up body composition assessment. Their BMI and waist circumference were increased by 2.01 ± 6.09 (p < 0.001) and 4.0 ± 13.7 cm (p = 0.02) respectively (Table 3). The longitudinal change in BMI significantly correlated with baseline serum albumin (r = 0.23, p = 0.01). In univariate model, serum albumin (unstandardized B 0.126, p = 0.014) predicted the longitudinal BMI change. However, the significance of serum albumin disappeared in multivariate model, in which age became the only independent predictor in this model (p = 0.03).

Longitudinal change in body composition

At 1 year, ATM increased by 3.3 ± 7.4 kg (p < 0.001), while their LTM only mildly reduced by 0.4 ± 7.6 kg (p = 0.5). Patients with higher adipose but not serum ZAG level tended to gain ATM and lose LTM with time (Fig. 3). Adipose ZAG level positively correlated with longitudinal change of ATM (r = 0.276, p = 0.004) and ICW (r = 0.286, p = 0.003), but inversely correlated with change of LTM (r = − 0.296, p = 0.002). In multivariate linear regression model, adipose ZAG expression remained as significant predictor of change in LTM, ATM and ICW (Table 4). In the same model, dialysis adequacy by total Kt/V also predicted ATM and ICW change. Serum albumin (unstandardized B 0.351, p = 0.040) predicted LTM change in univariate model, but its significance disappeared in multivariate model after adjustment for confounders. Dialysate dextrose load did not predict longitudinal change of ATM (p = 0.2) and LTM (p = 0.2).

Survival

Our patients were further followed for a total of 314.7 patient-years after body composition reassessments. During the period, 8 (6.8%) patients underwent kidney transplantation, and 31 (26.5%) patients died. The causes of death were infection (n = 13), ischemic heart disease (n = 11), cerebrovascular accident (n = 3), malignancy (n = 2) and others (n = 2). The average survival was 1.7 ± 0.6 years. Patients who died were older (p = 0.007) with a lower serum albumin level (p = 0.02). They also had a higher comorbidity load (p = 0.003) and were frailer (p < 0.001). Patients with lower serum ZAG expression experienced a stepwise significantly worse survival (log-rank test, p = 0.02) (Fig. 4). In multivariate model, serum ZAG level (p = 0.003), CFS (p < 0.001), baseline BMI (p = 0.04), LTM (p = 0.03) and ATM (p = 0.04) predicted all-cause survival (Table 5, Supplementary Table 2). Neither did longitudinal change of LTM and ATM predict survival in this model. Using the same group of covariates, serum ZAG (adjusted hazard ratio (AHR) 0.95, p = 0.045), CFS (AHR 3.40, p = 0.002), serum albumin (AHR 0.82, p = 0.04) and presence of ischemic heart disease (AHR 0.09, p = 0.02) independently predicted infection-related death, while presence of ischemic heart disease (AHR 3.65, p = 0.045) remained as the only predictor of cardiovascular-related death.

Discussion

This study provides novel evidence of adipose and serum ZAG expression and its relationship with cross-sectional and longitudinal change in body composition and functional state in incident dialysis patients. In essence, adipose and serum ZAG level inversely correlated with adiposity, whilst patients with high adipose ZAG expression tended to gain fat and lose lean tissue with time on dialysis. Moreover, our result characterized the significance of serum ZAG level in survival prediction, which is independent from traditional risk factors like baseline and serial change in body composition. Here we provide evidence to the potential use of adipose and serum ZAG quantification from adipose and serum samples as biomarkers of adiposity and longitudinal change of fat and lean tissue, as well as to predict mortality in incident dialysis patients.

To date, limited data exist on correlation between body composition and ZAG expression at adipose tissue from human patients with CKD. There was only one published study that quantified adipose ZAG expression in 7 stage 5 CKD patients11. Here we report an absence of correlation between adipose and serum ZAG expression, which was illustrated in the past11,14. Such finding reinforces a key message that measurement of circulating ZAG level, as most published studies did, could not be used to deduce its expression at adipose tissue level. This also suggests the primary function of ZAG as an autocrine or paracrine rather than endocrine polypeptide14,18. Although ZAG is highly produced in adipose tissue11 which is extensively perfused by an extensive network of blood vessels, only a few adipokines like adiponectin and leptin that can flow freely and readily into the systemic circulation22. Moreover, the mode and route of metabolism could also influence the circulating level. By far there is no dedicated study that explored the mechanism of ZAG metabolism and elimination, though observational studies suggested a potential renal excretion route as plasma ZAG level increases when kidney function declines10,11,12, and its level decreases after patients regain renal excretory function through kidney transplantation23. Dialysis therapy itself may influence the circulating ZAG level11. However, the contributory role of renal clearance is less prominent in patients with advanced CKD who have very low renal excretory function, as reflected by the absence of correlation between serum ZAG level and both uremia and residual renal function from our results. Furthermore, we did not identify any correlation between serum ZAG and the product of adipose ZAG concentration and all adiposity parameters. Such finding supports the notion that adipose tissue is only one of the circulating ZAG sources. As a matter of fact, ZAG is also produced in the epithelial cells of various organs e.g., mammary gland, prostate, sweat gland, etc.24, and these may also contribute to the circulating level.

Our result expands the current evidence on the inverse relationship between adiposity and circulating ZAG level. While Leal et al.25 and Hosseinzadeh-Attar et al.15 used skinfold thickness and BMI respectively as proxy of adiposity, we used bioimpedance method to characterize fat tissue volume. However, inaccurate measurement of fat mass has been reported by using skinfold thickness and BMI26,27. In contrast, bioimpedance-based assessment is a reliable and sensitive tool to determine volume of different body compartments. It gives information on lean tissue mass, adipose tissue mass and hydration volume. Bioimpedance-based method is a practical, inexpensive tool that can achieve the substantial agreement with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA)26, and it is currently a suggested method to assess body composition by the KDOQI guideline28.

Indeed, our dialysis patients gained a sizable amount of weight after dialysis initiation, which is predominantly contributed by fat mass gain, rather than lean tissue mass gain or overhydration. Such finding is in concordant with previous studies29,30,31, and this problem tends to be more apparent at the start of dialysis30. While diabetes mellitus, peritoneal dialysate glucose absorption1 predicted fat gain in peritoneal dialysis patients, we extend the understanding by illustrating adipose ZAG accelerated the process of adipose mass acquisition. Further study in animal model showed that zinc administration could induce adipose tissue hypertrophy32 and affect secretion of other adipokines18. The difference in change of body built between high and low ZAG level groups could be explained by regression to the mean phenomenon33, but the chance of such is low given the change in both LTM and ATM were all in one direction with just a difference in magnitude. Further study is warranted to identify whether ZAG or zinc-based treatment could revert the process of fat accumulation. Nonetheless, our patients with high adipose ZAG expression also experienced a greater loss in lean tissue mass. It could be explained by the fatty infiltration at the intermuscular region secondary to fat accumulation. This causes decline in muscle mass, quality and strength, which could eventually lead to reduction in physical performance, mobility, increase in fall risk and sequential development of frailty34. Moreover, ZAG positively correlates with both adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) and hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), which play critical roles in myocyte apoptosis and proteosomal muscle degradation35 and result in cachexia and lean tissue wasting.

Our result reinforced the observation that patients with high ZAG expression have a better survival. In this aspect, ZAG plays an important role in the anti-inflammation and anti-fibrotic process18,36, as it reduces oxidative stress through down regulation of various pro-atherogenic factors production e.g., tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1)37, etc. Together with its lipolytic effect, which results in a better lipid and glucose metabolism15, patients with high ZAG expression are less likely to develop coronary artery disease38. Likewise, ZAG also upregulates the activity of beta-2 adrenergic receptor39, which results in reduction in cardiac expression of type I, IV collagen and fibronectin and subsequent myocardial fibrosis. The use of beta-2 adrenergic receptor agonist has been proven to confer protective effect against cardiovascular complications through attenuation of monocyte activation, inflammatory and fibrotic responses in the heart40. The association with survival persisted after adjustment with baseline and trajectory of body composition after dialysis initiation. As baseline and trajectory of body composition, especially obesity, were identified as key factors for survival in dialysis patients41,42, this suggests these factors are likely merely proxies of ZAG expression.

Our reported results on serum ZAG with survival is different from that reported by Bouchara et al.16. Such discrepancy could be explained by several reasons. Firstly, the nature of subjects in the two studies are different. While Bouchara A’s study recruited prevalent hemodialysis (HD) patients, we recruited patients newly started on PD therapy. As a matter of fact, HD and PD patients represent two distinct groups of individuals since they have a different circulating ZAG profile43. Secondly, the timing of obtaining blood specimen (i.e., a pre-, mid-, or post- dialysis sample) was not clearly specified in Bouchara A’s study. In fact, serum ZAG fluctuates during HD. It was reported that pre-dialysis ZAG level differs from post-dialysis level11, and therefore interpretation of serum ZAG at different time point may lead to a different conclusion. Compared to HD, PD is characterized by a longer dialysis time with a continuous clearance of solute and toxins. Therefore, serum ZAG expression in PD should be more stable during a day between different time point. In addition to the traditional factors like age, gender, and albumin, we constructed a more comprehensive analysis model by adjusting our results for comorbidity load, frailty44, as well as the baseline and dynamic change of bioimpedance-derived body composition parameters45 to the regression model. These factors may account for the difference in the outcomes that we reported. In short, our result provides grounds supporting the use of serum ZAG quantification in mortality risk stratification.

Our study carries several limitations. Firstly, the power of our study is restricted by nature of single center study with a limited sample size, and we were unable to establish the causal relationship with outcome based on the intrinsic limitation of a cohort study. Secondly, the adipose tissue sample obtained during the operation may contain other cell types that may affect the ZAG assay. Since we obtained the serum sample approximately four weeks after peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion, there was a chance that dialysis therapy may affect ZAG expression, though the effect is expected to be minimal given a short duration of dialysis. Thirdly, we measured ZAG expression once only at baseline, thus we are unable to provide information on any longitudinal change in ZAG expression. Moreover, ZAG expression could be affected transiently by dietary habits, which were unmeasured in the current study. However, all our subjects received standard counselling on the proper amount of energy, fat, and protein intake by experienced dietitians at the start of study. We also reduced the confounding effects of such by adding metabolic and nutritional parameters such as albumin, lipids profile and BMI into the statistical analysis model. Furthermore, ZAG levels are also altered in acute stress conditions like sepsis and critical illnesses46,47,48, though we attempted to reduce the bias through exclusion of patients who were critically ill and unfit for peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion. Lastly, we did not evaluate other associated up- and down-stream biomarkers, therefore we are unable to infer the overall pathogenic pathway and establish the pathophysiological mechanisms with the clinical outcomes we studied.

In conclusion, adipose and serum ZAG levels significantly and positively correlated with adiposity in advanced CKD patients. Our finding also showed adipose ZAG predicted longitudinal change in adiposity and lean tissue wasting, which suggests that ZAG plays an important role in modulation of body composition. From the current study, we provided sufficient evidence to support the role of ZAG in survival prediction. Further observational and interventional studies are warranted to explore and establish to causal relationship and potential benefits of ZAG-based therapy.

Data availability

Data described in the manuscript will be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Law, S. & Davenport, A. Glucose absorption from peritoneal dialysate is associated with a gain in fat mass and a reduction in lean body mass in prevalent peritoneal dialysis patients. Br. J. Nutr. 123(11), 1269–1276 (2020).

Choy, A.S.-M. et al. Weight change during the first year of peritoneal dialysis: Risk factors and prognostic implications. Hong Kong J. Nephrol. 17(2), 28–35 (2015).

Keane, D. et al. Changes in body composition in the two years after initiation of haemodialysis: A retrospective cohort study. Nutrients 8, 11 (2016).

Visser, W. J., Egmond, A., Timman, R., Severs, D. & Hoorn, E. J. Risk factors for muscle loss in hemodialysis patients with high comorbidity. Nutrients 12, 9 (2020).

Kalantar-Zadeh, K. et al. Associations of body fat and its changes over time with quality of life and prospective mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 83(2), 202–210 (2006).

Cabezas-Rodriguez, I. et al. Influence of body mass index on the association of weight changes with mortality in hemodialysis patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 8(10), 1725–1733 (2013).

Wang, K., Zelnick, L. R., Chertow, G. M., Himmelfarb, J. & Bansal, N. Body composition changes following dialysis initiation and cardiovascular and mortality outcomes in CRIC (chronic renal insufficiency cohort): A bioimpedance analysis substudy. Kidney Med. 3(3), 327–334 (2021).

Kim, C., Kim, J. K., Lee, H. S., Kim, S. G. & Song, Y. R. Longitudinal changes in body composition are associated with all-cause mortality in patients on peritoneal dialysis. Clin. Nutr. 40(1), 120–126 (2021).

Than, W. H., Chan, G.C.-K., Ng, J.K.-C. & Szeto, C.-C. The role of obesity on chronic kidney disease development, progression, and cardiovascular complications. Adv. Biomark. Sci. Technol. 2, 24–34 (2020).

Pelletier, C. C. et al. The relationship between renal function and plasma concentration of the cachectic factor zinc-alpha2-glycoprotein (ZAG) in adult patients with chronic kidney disease. PLoS ONE 9(7), e103475 (2014).

Pelletier, C. C. et al. White adipose tissue overproduces the lipid-mobilizing factor zinc alpha2-glycoprotein in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 83(5), 878–886 (2013).

Philipp, A. et al. Serum levels of the adipokine zinc-alpha2-glycoprotein are increased in chronic hemodialysis. Metabolism 60(5), 669–672 (2011).

Banaszak, M., Gorna, I. & Przyslawski, J. Zinc and the innovative zinc-alpha2-glycoprotein adipokine play an important role in lipid metabolism: A critical review. Nutrients 13, 6 (2021).

Ceperuelo-Mallafre, V. et al. Circulating and adipose tissue gene expression of zinc-alpha2-glycoprotein in obesity: Its relationship with adipokine and lipolytic gene markers in subcutaneous and visceral fat. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 94(12), 5062–5069 (2009).

Hosseinzadeh-Attar, M. J., Mahdavi-Mazdeh, M., Yaseri, M., Zahed, N. S. & Alipoor, E. Comparative assessment of serum adipokines zinc-alpha2-glycoprotein and adipose triglyceride lipase, and cardiovascular risk factors between normal weight and obese patients with hemodialysis. Arch. Med. Res. 48(5), 459–466 (2017).

Bouchara, A. et al. Serum levels of the adipokine zinc-alpha2-glycoprotein (ZAG) predict mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 94(5), 983–992 (2018).

Sorensen-Zender, I. et al. Zinc-alpha2-glycoprotein in patients with acute and chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 14, 145 (2013).

Mracek, T. et al. The adipokine zinc-alpha2-glycoprotein (ZAG) is downregulated with fat mass expansion in obesity. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 72(3), 334–341 (2010).

Kwan, B. C. et al. Bioimpedance spectroscopy for the detection of fluid overload in Chinese peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit. Dial. Int. 34(4), 409–416 (2014).

Chan, G.C.-K. et al. Adipose expression of miR-130b and miR-17–5p with wasting, cardiovascular event and mortality in advanced chronic kidney disease patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2, 2 (2021).

Rockwood, K. & Theou, O. Using the clinical frailty scale in allocating scarce health care resources. Can. Geriatr. J. 23(3), 210–215 (2020).

Fain, J. N., Madan, A. K., Hiler, M. L., Cheema, P. & Bahouth, S. W. Comparison of the release of adipokines by adipose tissue, adipose tissue matrix, and adipocytes from visceral and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissues of obese humans. Endocrinology 145(5), 2273–2282 (2004).

Kraemer, T. D. et al. Changes in AZGP1 serum levels and correlation with pulse wave velocity after kidney transplantation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 692213 (2021).

Tada, T. et al. Immunohistochemical localization of Zn-alpha 2-glycoprotein in normal human tissues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 39(9), 1221–1226 (1991).

Leal, V. O. et al. Zinc-alpha2-glycoprotein: Is there association between this new adipokine and body composition in hemodialysis patients?. Ren. Fail. 34(9), 1062–1067 (2012).

de Abreu, A. M., Wilvert, L. C. & Wazlawik, E. Comparison of body mass index, skinfold thickness, and bioelectrical impedance analysis with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in hemodialysis patients. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 35(6), 1021–1028 (2020).

Dubey, A. K. et al. Reliability of anthropometry-based equations compared to dual energy absorptiometry for assessing body composition in predialysis chronic kidney disease—A longitudinal study. J. Ren. Nutr. 30(3), 216–222 (2020).

Ikizler, T. A. et al. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for nutrition in CKD: 2020 update. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 76(3 Suppl 1), S1–S107 (2020).

Lo, W. K. Metabolic syndrome and obesity in peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 35(1), 10–14 (2016).

Choi, S. J. et al. Changes in body fat mass in patients after starting peritoneal dialysis. Perit. Dial. Int. 31(1), 67–73 (2011).

Than, W. H. et al. The change in the prevalence of obesity and new-onset diabetes in Chinese peritoneal dialysis patients over 25 years. Clin. Kidney J. 2, 2 (2021).

Huang, X. et al. Chronic high dose zinc supplementation induces visceral adipose tissue hypertrophy without altering body weight in mice. Nutrients 9, 10 (2017).

Barnett, A. G., van der Pols, J. C. & Dobson, A. J. Regression to the mean: What it is and how to deal with it. Int. J. Epidemiol. 34(1), 215–220 (2005).

Addison, O., Marcus, R. L., Lastayo, P. C. & Ryan, A. S. Intermuscular fat: A review of the consequences and causes. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 309570 (2014).

Das, S. K. et al. Adipose triglyceride lipase contributes to cancer-associated cachexia. Science 333(6039), 233–238 (2011).

Sorensen-Zender, I. et al. Zinc-alpha2-glycoprotein exerts antifibrotic effects in kidney and heart. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26(11), 2659–2668 (2015).

Leal, V. O. et al. Is zinc-alpha2-glycoprotein a cardiovascular protective factor for patients undergoing hemodialysis?. Clin. Chim. Acta. 413(5–6), 616–619 (2012).

Liu, M. et al. Serum zinc-alpha2-glycoprotein levels were decreased in patients with premature coronary artery disease. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 10, 197 (2019).

Russell, S. T. & Tisdale, M. J. Role of beta-adrenergic receptors in the anti-obesity and anti-diabetic effects of zinc-alpha2-glycoprotien (ZAG). Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1821(4), 590–599 (2012).

Noh, H. et al. Beta 2-adrenergic receptor agonists are novel regulators of macrophage activation in diabetic renal and cardiovascular complications. Kidney Int. 92(1), 101–113 (2017).

Kittiskulnam, P. & Johansen, K. L. The obesity paradox: A further consideration in dialysis patients. Semin. Dial. 32(6), 485–489 (2019).

Chang, T. I. et al. Association of body weight changes with mortality in incident hemodialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 32(9), 1549–1558 (2017).

Schmitt, R. ZAG-a novel biomarker for cardiovascular risk in ESRD patients?. Kidney Int. 94(5), 858–860 (2018).

Chan, G. C. et al. Depression does not predict clinical outcome of Chinese peritoneal dialysis patients after adjusting for the degree of frailty. BMC Nephrol. 21(1), 329 (2020).

Marcelli, D. et al. Body composition and survival in dialysis patients: Results from an international cohort study. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10(7), 1192–1200 (2015).

Welters, I. D., Bing, C., Ding, C., Leuwer, M. & Hall, A. M. Circulating anti-inflammatory adipokines High Molecular Weight Adiponectin and Zinc-alpha2-glycoprotein (ZAG) are inhibited in early sepsis, but increase with clinical recovery: A pilot study. BMC Anesthesiol. 14, 124 (2014).

Escote, X. et al. Zinc alpha-2 glycoprotein is overproduced in Cushing’s syndrome. Endocrinol. Diabetes Nutr. 64(1), 26–33 (2017).

Zhang, W. et al. Zinc-alpha2-glycoprotein knockout influenced genes expression profile in adipose tissue and decreased the lipid mobilizing after dexamethasone treatment in mice. Horm. Metab. Res. 52(10), 755–763 (2020).

Funding

This study was supported in part by the Hong Kong Society of Nephrology Research Grant, the Richard Yu Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) PD Research Fund, and CUHK research accounts 6905134 and 8601286. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.C.-K.C.: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, project administration. W.H.T.: data curation, investigation. B.C.-H.K.: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, project administration. K.-B.L.: Investigation. R.C.-K.C.: investigation. J.Y.-C.T.: investigation. J.K.-C.N.: investigation, data curation, writing—review & editing. K.-M.C.: investigation. W.W.-S.F.: investigation. P.M.-S.C.: investigation. M.-C.L.: investigation. C.-B.L.: investigation. P.K.-T.L.: supervision. C.-C.S.: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing—review & editing, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, G.CK., Than, W.H., Kwan, B.CH. et al. Adipose and serum zinc alpha-2-glycoprotein (ZAG) expressions predict longitudinal change of adiposity, wasting and predict survival in dialysis patients. Sci Rep 12, 9087 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13149-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13149-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.