Abstract

Interspecies hybrids can express phenotypic traits far outside the range of parental species. The atypical traits of hybrids provide insight into differences in the factors that regulate the expression of these traits in the parental species. In some cases, the unusual phenotypic traits of hybrids can lead to phenotypic dysfunction with hybrids experiencing reduced survival or reproduction. Cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs) in insects are important phenotypic traits that serve several functions, including desiccation resistance and pheromones for mating. We used gas chromatography mass spectrometry to investigate the differences in CHC production between two closely related sympatric Hawaiian picture-wing Drosophila species, Drosophila heteroneura and D. silvestris, and their F1 and backcross hybrid offspring. CHC profiles differed between males of the two species, with substantial sexual dimorphism in D. silvestris but limited sexual dimorphism in D. heteroneura. Surprisingly, F1 hybrids did not produce three CHCs, and the abundances of several other CHCs occurred outside the ranges present in the two parental species. Backcross hybrids produced all CHCs with greater variation than observed in F1 or parental species. Overall, these results suggest that the production of CHCs was disrupted in F1 and backcross hybrids, which may have important consequences for their survival or reproduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Interspecies hybrids that express phenotypic traits far outside the range present in the parental species can provide insights into the factors that regulate the expression of these traits1. These unusual phenotypic traits in hybrids can also reflect a type of phenotypic dysfunction in which hybrid individuals experience reduced survival or reproduction2,3. Several types of gene interactions may be involved in hybrid disruption, such as cis–trans regulation or post-transcriptional processes, including mRNA splicing and processing4,5. Further, translational alterations resulting in changed amino acids may result in proteins incapable of interacting, thus producing less-fit hybrid phenotypes6.

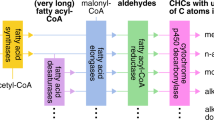

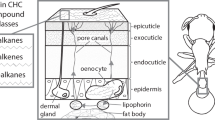

Cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs) are abundant components of insect cuticles7,8 that are produced through complex biochemical processes9,10 and involve the interaction of genes on different chromosomes11. CHCs display a wide range of distinct compounds that vary across insect taxa and occur as a complex mixture of hydrophobic linear, branched, saturated, and unsaturated compounds11,12,13. CHCs are known to act as pheromones and influence a wide variety of behaviors, including courtship, mate discrimination, learning, aggregation, and dominance5,8,14, and they have a strong influence on individual fitness, helping insects to resist starvation15, tolerate extreme environments16, and prevent desiccation17,18,19. In D. melanogaster, the alteration or disruption of genes involved in CHC biosynthesis can result in the complete absence20 or over-production21 of CHCs, changes that have the potential to negatively impact mating, copulation behavior, and survivability10,22.

The Hawaiian picture-wing Drosophila are a species-rich radiation that vary in CHCs with some species subgroups displaying more linear alkanes and unsaturated hydrocarbons and other subgroups possessing more monomethylalkanes and dimethylalkanes13. In the well-studied planitibia subgroup, nearly all species display the same main hydrocarbons with subtle but significant quantitative differences among species in the abundances of specific compounds and limited sexual dimorphism. A single exception, D. silvestris, shows strong sexual dimorphism in CHC composition as well as differences in the abundances of compounds in males (e.g. greater 2MeC30 and less 2MeC26) compared to the other species in the subgroup13.

Drosophila heteroneura and D. silvestris are sister species within the planitibia subgroup of the Hawaiian picture-wings23 that occupy the same larval host plant (Clermontia spp) and have coexisted at several locations on Hawaii Island24. Despite their shared ecology and plant host, they are morphologically and behaviorally distinct25. Divergence in CHC abundances between D. silvestris and D. heteroneura—apparently due to evolution of D. silvestris males (see above)—occurred recently (i.e., < 1 million years ago)23 as the two species became established on Hawaii Island. These two species are known to hybridize in nature, as both F1 and backcross individuals have been collected in the wild24. Under laboratory conditions these two species readily hybridize to yield fertile F1 progeny that differs from both species with respect to behavioral and morphological characters26,27. F1 hybrid females and males can be mated with each parental species to create backcross individuals that exhibit wide genetic and phenotypic variation due to recombination of the genes from the two parental species28. Recent genome comparisons of D. heteroneura and D. silvestris indicate that there was gene flow between these two species after their arrival on Hawaii Island from an older island29, and these species show significant sequence divergence for olfactory and gustatory genes that may be important in chemical communication30.

The ability to hybridize species in the laboratory allows the controlled examination of phenotypes in parental, F1 and backcross individuals to better understand the genetic basis of species differences, including differences in the regulation of gene expression. We examined the CHCs in laboratory populations of D. heteroneura and D. silvestris and their F1 and backcross hybrids. The CHC profiles of F1 and backcross hybrids displayed intermediate abundances of some CHCs and unusual amounts of other CHCs. Notably, a third group of CHCs was completely absence in F1 individuals. The disrupted production of CHCs in hybrids suggests that there are important differences between D. heteroneura and D. silvestris in the regulation of CHC production that have evolved since these species were founded on Hawaii Island. The importance of these differences for ecological adaptation or reproduction in D. silvestris and D. heteroneura remains to be determined.

Materials and methods

Hawaiian Drosophila population rearing

The populations of D. silvestris and D. heteroneura used in this study were initiated with individuals collected in the wild from the South Kona Forest Reserve, Kukuiopae (e 1: GPS coordinates 19.2972818613052, − 155.8117108345032) on the 16–17th of December 2012 and 29th of December 2009, respectively. Flies were attracted to baits comprising a fermented banana-yeast medium and fermented-mushroom spray spread on sponges and hung one to two meters from the ground near patches of Cheirodendron trigynum and Clermontia sp. The flies were captured using an aspirator and were immediately transferred to sugar-agar vials. The vials were transported to the University of Hawai’i at Hilo where individuals were identified to species and placed in one-gallon breeding jars. Populations of both species were maintained in an environmentally controlled room, following Hawaiian Drosophila-specific rearing procedures described in Price and Boake27. F1 hybrids were produced by placing one mature D. silvestris or D. heteroneura male with one or two D. silvestris or D. heteroneura females. For each of the two cross types, 50 groups of males and females were founded, with breeding individuals being replaced as they died. Breeding individuals were housed in a mating vial with adult food and a tissue soaked in Clermontia spp. leaf tea27. Adults were transferred to new vials every 4 days, and old mating vials were placed in larvae-rearing trays. After four weeks, larvae vials were placed in emergence jars, and emerged individuals were aspirated into jars weekly according to their respective genotype and sex. The production of backcross individuals was achieved in the same manner by mating F1 females from each parental cross (D. silvestris females x D. heteroneura males and D. heteroneura females by D. silvestris males) to mature males of each parental species (D. heteroneura and D. silvestris). The two types of backcross males were BC—S, males produced by mating F1 females with D. silvestris males; and BC—H, males produced by mating F1 females with D. heteroneura males: 20–30 pairs were used for the production of each backcross type.

Chemical analysis of cuticular hydrocarbons

Cuticular hydrocarbon extractions were obtained by placing individual flies in 4-ml vials which were held at − 80 °C for 10 min. After euthanization, 1 mL of hexane was added to each vial. Vials were then gently agitated for 10 min. The solvent from each sample was then transferred to a new clean 2-mL screw-top vial, and the volume was reduced to 30 uL under a stream of nitrogen gas. Extracts were stored at − 80 °C until used for analysis. All flies used for CHC analysis were 28–30-day-old virgin males and females. In the analysis of F1 hybrids and parental species, 320 ng of eicosane, as an internal standard, was also added to each vial to obtain absolute abundances.

Two gas chromatograph (GC) instruments were used to analyze CHC profiles. GC–MS analysis to identify CHCs was performed on an Agilent (Palo Alto, CA, USA) 6890 N GC interfaced with a Hewlett-Packard 5973 Mass Selective Detector. The GC was equipped with an HP-5MS column (30 m × 0.25 mm ID 0.25-μm film thickness), which was temperature-programmed from 180 to 320 °C at 3 °C min−1 following a 1-min delay. The injector temperature was 250 °C with the MS transfer line at 280 °C, and helium was the carrier gas (1.1 ml min−1). Detected CHCs were identified based on analyses of their mass spectra, retention indices, and comparison with the NIST08 mass spectral database and literature chromatographic data (Alves et al. 2010).

Quantification of CHCs in D. heteroneura, D. silvestris, F1 hybrid, and backcross individuals was done using an Agilent 6890 GC equipped with a flame-ionization detector (FID) and an HP-5 column (30 m × 0.25 mm ID 0.25-μm film thickness), with helium as the carrier gas (2.3 ml min−1). The injector, in splitless mode, and FID were held at 250 °C and 275 °C, respectively. The oven temperature program ran from 180 to 320 °C at 3 °C min−1 following a 1-min delay. Peak areas of major CHCs in each fly were quantified using ChemStation software (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California), and individual compounds were normalized to the standard.

Statistical analysis

The differences in CHC profiles among parental species, F1 hybrids, and backcross individuals were analyzed using T-tests, ANOVAs, principal components analyses (PCA), and logistic regression analysis using R × 64 3.1.1 and Minitab version 16. Tukey’s multiple-comparison tests were conducted to determine the groups that were significantly different following ANOVA. PCA were conducted to account for the underlying correlation structure among the compounds.

Results

The nine major CHCs detected were 2-methylhexacosane (2MeC26), 2-methyloctacosane (2MeC28), 2-methyltriacontane (2MeC30), 11 + 13-dimethylhentriacontane (11 + 13MeC31), 11,15-dimethylhentriacontane (11,15diMeC31), 2-methyldotriacontane (2MeC32), 11 + 13-dimethyltritriacontane (11 + 13MeC33), 11,15-dimethyltritriacontane (11,15diMeC33) and 11,15-dimethylpentatriacontane (11,15diMeC35). The pairs of compounds 11MeC31 and 13MeC31, along with 11MeC33 and 13MeC33, are known to coelute and have nearly identical mass spectra making absolute structural identification difficult. Therefore, the abbreviations 11 + 13MeC31 were used to indicate ambiguous identification of these peaks.

Parental and F1 hybrid analyses

The correlation structure of compound abundances differed between both species and sexes (Tables S1 and S2). Viewing just the strongest positive and negative pairwise correlations (i.e. r >|0.6|) between compounds revealed highly constrasting patterns among the four groups (Fig. 1), suggesting variation in the regulation of compounds production between sexes and between species.

Correlation graph showing the strongest correlations among the nine CHCs in the parental species. D. heteroneura females (n = 10) in the upper left, D. silvestris females (n = 10) in the upper right, D. heteroneura males (n = 10) in the lower left and D. silvestris males (n = 10) in the lower right panel. The solid lines indicate the strongly positive correlations (r > 0.6, P < 0.05), and the dashed lines indicate the strongly negative correlations (r < − 0.6, P < 0.05), between compounds. Graph drawn in MSWord from correlations between CHCs in females and males of both species presented in Tables S1 and S2.

Surprisingly, three of the nine compounds detected in the parental species were absent in both F1 females and males: 11 + 13MeC31, 11,15diMeC31, and 2MeC32 (Table S3). The mean relative percent abundances of each of the six CHCs detected in F1 hybrids and each species are reported in Table 1. The relative abundances of the six compounds in D. heteroneura, D. silvestris and F1 hybrid individuals were interdependent with some compounds highly significantly correlated (Table S4). In addition, the mean nanogram quantities for all nine CHCs, using the internal chemical standard, showed that the F1 individuals have reduced overall CHC production compared to D. heteroneura and D. silvestris (Table S3). D. heteroneura females also had a slightly lower total CHC production compared to the other parental species individuals.

For the six compounds observed in F1 individuals, the PCA of D. heteroneura, D silvestris, and their F1 hybrid females and males resulted in the first principal component (PC1) explaining 47.2% of the overall variation (Table S5). Three compounds showed positive loadings (2MeC26, 11,15diMe33, and 11,15diMeC35) and three compounds showed negative loadings (2MeC328, 2MeC30 and 11 + 13MeC33). PC2 explained 34.5% of the overall variation and had negative loadings for 2MeC26 and 2MeC28 and positive loadings for the other four compounds. PC3 explained 13.9% of the overall variation with a negative loading of two components (2MeC26 and 11 + 13MeC33) and positive loadings for the other components (Table S5).

Drosophila heteroneura and D. silvestris males exhibited significant differences for both PC1 and PC2 scores with F1 males intermediate between the two parental males on PC1 and similar to D. silvestris on PC2 (Fig. 2A and Table S6). D. heteroneura and D. silvestris females were more similar but significantly different for PC1 and PC2 with F1 females outside the range and significantly different from females of the two parental species for both PC1 and PC2 (Table S6). Interestingly, the F1 females and males differed significantly for PC1 and PC2 scores. D. silvestris, but not D. heteroneura, showed strong and significant sexual dimorphism for both PC1 and PC2 scores (Fig. 2A and Table S4).

Scatterplot of principal component scores with ordinations representing differences in CHC compositions among genotypes for PC1 and PC2. (A) Parental and F1 hybrid females and males from the analysis of the six compounds found in F1 individuals. PC1 explained 47.2%, and PC2 explained 34.5% of the overall variation in the six CHCs (see Table S5). (B) Parental and backcross males from analysis of all nine compounds found in parental and backcross individuals. PC1 explained 51.6%, and PC2 explained 13.5% of the overall variation in the nine CHCs (see Table S9). (C) Parental and backcross females from analysis of all nine compounds found in parental and backcross individuals. PC1 explained 49.3%, and PC2 explained 21.6% of the overall variation in the nine CHCs (see Table S10. Symbols: D. heteroneura (Het), D. silvestris (Sil), F1 Hybrid (F1), BC—H backcross to D. heteroneura, and BC—S backcrossed to D. silvestris.

For all but one individual compound, the mean relative abundances of CHCs differed significantly between D. heteroneura and D. silvestris males (Table 1 and Table S3). Four of these compounds also differed in abundances between D. heteroneura and D. silvestris females: 2Me26, 2MeC30, and 11,15diM3C31 and 11,15diMeC33. D. silvestris females and males differed significantly in the relative abundances of five compounds (2MeC28, 2MeC30, 11,15diMeC31, 11 + 13MeC33, and 11,15diMeC33), while D. heteroneura females and males differed significantly for three compounds (2Me26, 11,15diMeC31, 2MeC32) (Table 1 and Table S3). For F1 males, the mean relative abundances of three compounds were intermediate between those for D. heteroneura and D. silvestris males (2Me26, 2Me30, 11 + 13MeC33), while the abundances of three compounds were less than those of both parental species. For F1 females, the mean abundances of two compounds were close to those of D. silvestris females (2Me26 and 2Me30), while three compounds were less abundant, and one compound was more abundant, in F1 females compared to females of the two parental species.

Parental and backcross analyses

All nine CHCs that were detected in the parental species were also detected in backcross males and females (Tables 2 and 3) with the abundances of some of the CHCs significantly correlated within each sex (Tables S7 and S8). The PCA resulted in PC1 explaining 51.6% of the total variation for male genotypes and 49.3% for female genotypes (Tables S9 and S10). There were similar positive loadings for six of the CHCs and negative loadings for two of the CHCs for both males and females. PC2 explained 13.5% and 21.6% of the total variation in CHC composition of males and females, respectively. The three remaining principal components explained 10% or less of the total variation for both males and females (Tables S9 and S10).

PC1 scores for CHC abundance in the two classes of backcross males were closer to the parental species to which they were backcrossed but unique to each class of males (Fig. 2B,C; Table S11). For PC2 and PC3, the backcross males were not significantly different from D. silvestris and D. heteroneura males. Both types of backcross females were closer in overall CHC abundances to D. heteroneura females for PC1 and significantly different from D. silvestris; in contrast, for PC2, both backcross females were significantly different from D. heteroneura but not from D. silvestris females (Fig. 2C, Table S12).

The abundances of individual compounds showed a range of patterns across backcross and parental-species genotypes. Four compounds (2MeC26, 2MeC28, 2MeC30, and 11 + 13MeC31) differed significantly in abundance between BC-H and BC-S backcross males, being similar in abundances to the same compounds in the parental species to which they were backcrossed. For the 11,15diMeC31 compound, the backcross males were significantly different from D. heteroneura and similar to D. silvestris (Table 2). The other compounds (2MeC32, 11 + 13MeC33, 11,15diMeC33, 11,15diMeC35) did not differ between the BC-H and BC-S backcross males, generally showing abundances intermediate to those of males of the two parental species. Similarly, the abundances of individual compounds in BC-H and BC-S backcross females differed significantly from each other for three compounds (Table 3: 2MeC26, 2MeC28, and 11 + 13MeC31). For 2MeC30 and 11,15diMeC33, the two types of backcross females were similar to each other and significantly different from both parental species with the abundance of 11,15diMeC33 outside the range of the parental species. The two backcross females differed significantly from D. silvestris, but not D. heteroneura for 11,15diMeC31, and both backcross females differed from D. heteroneura but not D. silvestris for 11,15diMeC35. The abundance of 2MeC32 and 11,15MeC33 in the backcross females did not differ significantly from that for D. silvestris, with BC-H females showing significant differences from D. heteroneura for 11,15MeC33 (Table 3).

Discussion

This study examined the abundances of nine CHC compounds in two sympatric Hawaiian Drosophila species and their hybrids and found significant differences between the species and evidence of phenotypic disruption in both F1 and backcross hybrids. The differences in the correlation structure of CHC abundances between D. heteroneura and D. silvestris suggests that there may be an alteration in the regulation of CHC production that contributes to the phenotypic disruption in the hybrids. The species also differed in the abundances of most of the nine CHCs measured, with D. silvestris males exhibiting unique patterns of the overall abundances and ratios of compounds expressed. Alves et al.13 also observed that D. silvestris males exhibited the greatest differences in CHC abundances compared to two other closely related species in the planitibia subgroup, D. hemipeza from Oahu and D. planitibia from Maui. This suggests that there may have been a recent evolutionary change in CHC production in males of D. silvestris during the relatively brief history of this young species on Hawaii Island.

Phenotypic disruption of CHCs was extensive in both female and male hybrids between D. silvestris and D. heteroneura. Three of the nine CHCs were absent in F1 hybrids of both sexes, which translated to overall lower absolute CHC production in F1 hybrids compared to the parental species. For the six other compounds, F1 individuals were intermediate for PC1 scores but outside the range of the two parental species for PC2 scores with some individual compounds intermediate and others outside of the range of the parental species. Interestingly, all nine compounds were detected in backcross hybrids, where they showed greater variation in abundances in both females and males with some individuals more like the parental species and others more similar to the F1 hybrids. This type of alteration in F1 and backcrossed hybrids has also been shown in D. simulans and D. sechellia5,31.

The presence of CHCs in F1 and backcross hybrids in abundances outside of the range observed in D. silvestris and D. heteroneura, including the complete absence of CHCs in F1 hybrids, suggests a disruption in the biochemical and regulatory processes underlying these compounds in hybrids as a result of divergence of the parental species. Inter-species hybrids often experience failures in gene expression and regulation, which, may contribute to phenotypic dysfunction3. Several types of gene interactions may underlie hybrid dysfunctions such as cis–trans regulation and post-transcriptional processes, including mRNA splicing and processing4,5. CHC biosynthesis involves long-chain fatty acid synthesis via elongation, the transformation of long-chain fatty acids to aldehydes, and an oxidative decarboxylation phase9,11,20,32. The suppression or disruption of any gene involved in the biosynthesis of CHCs may lead to the loss or alteration of an enzyme necessary to produce a critical precursor essential for proper CHC synthesis32,33. For example, the oenocyte-specific knockdown in D. melanogaster of the expression of Cyp4g1, a gene involved in transforming aldehydes to hydrocarbons, resulted in a significant loss of detectable CHCs20. It has also been shown that the disruption of the NADH dehydrogenases CG8680 and CG5599 results in increased CHC production in D. melanogaster females and males21. A particular elongase or enzyme involved in the production of the dimethyl C31 and methyl C32 components may have been disrupted during the formation of the F1 hybrids in this study, resulting in the missing compounds (11 + 13MeC31, 11,15diMeC31, and 2MeC32). Desaturases and elongases involved in CHC production are known to evolve rapidly may contribute to between-sex variation, speciation and phenotypic disruption in hybrids34,35,36.

Evolutionary changes in the cis-regulatory regions of genes in the biochemical pathways of CHCs could lead to important differences in CHC abundances between closely related species5,10,11,32. For example, in D. simulans and D. mauritiana, hybrid females display CHC profiles that are intermediate to, but significantly different from, the two parental species, consistent with divergence at cis-regulatory regions36. Throughout the Drosophila genus the expression of the desaturase, DESAT-F, is correlated with long-chain CHC production, and this compound has undergone numerous alterations37. Due to the specificity of these pathways, it is possible that in closely related species there has been a change in the regulation of genes involved in the production of some CHCs11. CHC production may also involve complex interactions between genes on different chromosomes that result in altered phenotypes in hybrids11. For example, studies conducted by Noor and Coyne38 correlated two CHCs in D. pseudoobscura and D. persimilis with X and second chromosome effects in backcross males. However, in backcross females only the second chromosome significantly influenced the CHC phenotype. There is the potential for epistatic genetic effects in the mating isolation between D. silvestris and D. heteroneura28, and the difference in head shape in D. silvestris and D. heteroneura has been shown to have an X-effect and some autosomal genetic effects26,39.

The results presented here add to a growing number of studies that demonstrate that hybrids between species can experience substantial changes in gene expression and regulation contributing to phenotypic disruption1,2,3,5. In genus Drosophila, hybrid male sterility has been associated with changes in gene expression in F1 hybrids of D. simulans and D. mauritiana40,41, D. melanogaster and D. simulans42, D. pseudoobscura pseudoobscura and D. p. bogotana43,44 and F1 and backcross hybrids in two Hawaiian picture-wing Drosophila, D. planitibia and D. silvestris45,46. Similarly, hybrid disruption for brain morphology and neural gene expression was recently shown in two closely related sympatric Heliconius butterfly species1.

The differences in the relative abundances and ratios of CHC compounds between D. silvestris and D. heteroneura reported here and by Alves et al.13 suggests that CHCs may contribute to the behavioral reproductive isolation between these species27,47,48. Evolutionary changes in chemosensory systems between species have been shown to contribute to reproductive isolation and speciation through changes in the production and reception of CHCs49. These changes can involve the gain or loss of specific compounds49 or changes in the ratios of compounds5,32,50. Furthermore, the phenotypic disruption of CHCs could decrease F1 and backcross hybrid fitness through reduced dessication resistance and mating with parental species.

In summary, the two Hawaiian picture-wing Drosophila, D. heteroneura and D. silvestris, differed in the abundances of several CHCs and showed sexual dimorphism for some of these compounds. D. silvestris males appear to have diverged to a greater extent in CHC abundances compared to males of other species within the planitibia clade of Hawaiian picture-wing Drosophila13. The phenotypic disruption in F1 and backcross hybrids may have important consequences for the survival or reproductive success of hybrid individuals. These results also suggest that the biochemical pathways underlying CHC synthesis have diverged between these two closely related species. Additional studies are required with more extensive sampling, additional genetic analyses (e.g., Quantitative Trait Loci analyses) combined with genomic and gene expression analyses to better understand the changes in CHC production and the associated biochemical pathways43,44,51,52. Although the function of these CHCs in D. silvestris and D. heteroneura are still unknown, divergence in CHC abundance has been recent, as the two species appear to have diverged less than 1 million years ago23. It will be important to determine whether the differences in CHC abundances and the significant sequence divergence for chemosensory genes30 observed in these species has resulted in changes in chemosensory responses in D. silvestris and D. heteroneura and contribute to the behavioral reproductive isolation between them27,48.

References

Montgomery, S. H., Rossi, M., McMillan, W. O. & Merrill, R. M. Neural divergence and hybrid disruption between ecologically isolated Heliconius butterflies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2015102118 (2021).

Fitzpatrick, B. M. Hybrid dysfunction: Population genetic and quantitative genetic perspectives. Am. Nat. 171, 491–498 (2008).

Orr, H. A. & Presgraves, D. Speciation by postzygotic isolation: Forces, genes and molecules. BioEssays 22, 1085–1094 (2000).

Braidotti, G. & Barlow, D. Identification of a male meiosis-specific gene, Tcte2, which is differently spliced in species that form sterile hybrids with laboratory mice and deleted t chromosomes showing meiotic division. Dev. Biol. 86, 85–99 (1997).

Combs, P. A. et al. Tissue-specific cis-regulatory divergence implicates eloF in inhibiting interspecies mating in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 28, 3969–3975 (2018).

Rawson, P. D. & Burton, R. Functional coadaptation between cytochrome c and cytochrome c oxidase within allopatric populations of a marine copepod. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 12955–12958 (2002).

Pedigo, L. P. & Rice, M. Entomology and Pest Management 6th edn. (Prentice-Hall International, 2009).

Yew, J. Y. & Chung, H. Insect pheromones: An overview of function, form, and discovery. Prog. Lipid Res. 59, 88–105 (2015).

Howard, R. W. & Blomquist., G. J. Ecological, behavioral, and biochemical aspects of insect hydrocarbons. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 50, 371–393 (2005).

Chung, H. & Carroll, S. B. Wax, sex and the origin of species: Dual roles of insect cuticular hydrocarbons in adaptation and mating. BioEssays 37, 822–830 (2015).

Holze, H., Schrader, L. & Buellesbach, J. Advances in deciphering the genetic basis of insect cuticular hydrocarbon biosynthesis and variation. Heredity 126, 219–234 (2021).

Liimatainen, J. & Jallon, J. Genetic analysis of cuticular hydrocarbons and their effect on courtship in Drosophila virilis and D. lummei. Behav. Gene 37, 713–725 (2007).

Alves, H. et al. Evolution of cuticular hydrocarbons of Hawaiian Drosophilidae. Behav. Genet. 40, 694–705 (2010).

Tillman, J. A., Seybold, S. J., Jurenka, R. A. & Blomquist, G. J. Insect heromones: An overview of biosynthesis and endocrine regulation. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 29, 481–514 (1999).

Hoffmann, A. A., Sorenson, J. G. & Loeschcke, V. Adaptation of Drosophila to temperature extremes: Bringing together quantitative and molecular approaches. J. Therm. Biol. 28, 175–216 (2003).

Ohtsu, T., Kimura, M. T. & Katagiri, C. How Drosophila species acquire cold tolerance: Qualitative changes of phospholipids. European J Biochemistry 252, 608–611 (1998).

Toolson, E. C. Interindividual variation in epicuticular hydrocarbon composition and water loss rates of the cicada Tibicen dealbatus (Homoptera: Cicadidae). Physiol. Zool. 57, 550–556 (1984).

Lockey, K. H. Insect hydrocarbon classes: Implications for chemotaxonomy. Insect. Biochem. 21, 91–97 (1991).

Gibbs, A. & Pomonis, J. G. Physical properties of insect cuticular hydrocarbons: The effects of chain length, methyl-branching and unsaturation. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 112, 243–249 (1995).

Qiu, Y., Tittiger, C., Wicker-Thomas, C. & Le Goff, G. An insectspecific P450 oxidative decarbonylase for cuticular hydrocarbon biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 14858–14863 (2012).

Dembeck, L. M. et al. Genetic architecture of natural variation in cuticular hydrocarbon composition in Drosophila melanogaster. Elife 4, e09861. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.09861 (2015).

Savarit, F., Sureau, G., Cobb, M. & Ferveur, J. F. Genetic elimination of known pheromones reveals the fundamental chemical bases of mating and isolation in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 9015–9020 (1999).

Magnacca, K. N. & Price, D. K. Rapid adaptive radiation and host plant conservation in the Hawaiian picture wing Drosophila (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 92, 226–242 (2015).

Carson, H. L., Kaneshiro, K. Y. & Val, F. C. Natural hybridization between the sympatric Hawaiian species Drosophila silvestris and Drosophila heteroneura. Evolution 43, 190–302 (1989).

Kaneshiro, K. Y. & Boake, C. R. B. Sexual selection and speciation: Issues raised by Hawaiian Drosophila. TREE 2, 207–212 (1987).

Val, F. C. Genetic analysis of the morphological differences between two interfertile species of Hawaiian Drosophila. Evolution 31, 611–629 (1977).

Price, D. K. & Boake, C. R. B. Behavioral reproductive isolation in Drosophila silvestris, D. heteroneura and their F1 hybrids. J. Insect Behav. 8, 595–616 (1995).

Price, D. K., Sounder, S. & Russo-Tait, T. Sexual selection, epistasis and species boundaries in sympatric hawaiian picture-winged Drosophila. J. Insect Behav. 27, 27–40 (2013).

Kang, L., Garner, H. R., Price, D. K. & Michalak, P. A test for gene flow among sympatric and allopatric hawaiian picture-winged Drosophila. J. Mol. Evol. 84, 259–266 (2017).

Kang, L. et al. Genomic signatures of speciation in sympatric and allopatric Hawaiian picture-winged Drosophila. Genome Biol. Evol. 8, 1482–1488 (2016).

Gleason, J. M., James, R. A., Wicker-Thomas, C. & Ritchie, M. G. Identification of quantitative trait loci function through analysis of multiple cuticular hydrocarbons differing between Drosophila simulans and Drosophila sechellia females. Heredity 103, 416–424 (2009).

Chung, H. I. et al. Single gene affects both ecological divergence and mate choice in Drosophila. Science 343, 1148–1151 (2014).

Ward, H. K. & Moehring, A. J. Genes underlying species differences in cuticular hydrocarbon production between Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans. Genome 64, 87–95 (2021).

Chertemps, T., Duportets, L., Labeur, C. & Wicker-Thomas., C. A new elongase selectively expressed in Drosophila male reproductive system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 333, 1066–1072 (2005).

Chertemps, T. et al. A female-biased expressed elongase involved in long-chain hydrocarbon biosynthesis and courtship behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 4273–4278 (2007).

Serrato-Capuchina, A. et al. Pure species discriminate against hybrids in the Drosophila melanogaster species subgroup. Evolution 75, 1753–1774 (2020).

Finet, C., Slavik, K., Pu, J., Carroll, S. B. & Chung, H. Birth-and-Death evolution of the Fatty Acyl-CoA Reductase (FAR) gene family and diversification of cuticular ydrocarbon synthesis in Drosophila. Genome Biol. Evol. 11, 1541–1551 (2019).

Noor, M. A. F. & Coyne, J. A. Genetics of a difference in cuticular hydrocarbons between Drosophila pseudoobscura and D. persimilis. Genet. Res. 68, 117–123 (1996).

Templeton, A. R. Analysis of head shape differences between two interfertile species of Hawaiian Drosophila. Evolution 31, 630–641 (1977).

Michalak, P. & Noor, M. Genome-wide patterns of expression in Drosophila pure species and hybrid males. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20, 1070–1076 (2003).

Michalak, P. & Noor, M. Association of misexpression with sterility in hybrids of Drosophila simulans and D. mauritiana. J. Mol. Evol. 59, 277–282 (2004).

Landry, C. R. et al. Compensatory cis-trans evolution and the dysregulation of gene expression in interspecific hybrids of Drosophila. Genetics 171, 1813–1822 (2005).

Gomes, S. & Civetta, A. Hybrid male sterility and genome-wide misexpression of male reproductive proteases. Sci. Rep. 5, 11976 (2015).

Go, A. C. & Civetta, A. Divergence of X-linked trans regulatory proteins and the misexpression of gene targets in sterile Drosophila pseudoobscura hybrids. BMC Genom. 23, 30 (2022).

Craddock, E. M. Reproductive relationships between homosequential species of Hawaiian Drosophila. Evolution 28, 593–606 (1974).

Brill, E., Kang, L., Michalak, K., Michalak, P. & Price, D. K. Hybrid sterility and evolution in Hawaiian Drosophila: Differential gene and allele-specific expression analysis of backcross males. Heredity 117, 100–108 (2016).

Boake, C. R. B., Price, D. K. & Andreadis, D. K. Inheritance of behavioural differences between two interfertile, sympatric species, Drosophila silvestris and D. heteroneura. Heredity 80, 642–650 (1998).

Kaneshiro, K. Y. Ethological isolation and phylogeny in the planitibia subgroup of Hawaiian Drosophila. Evolution 30, 740–745 (1976).

Shirangi, T. R., Dufour, H. D., Williams, T. M. & Carroll, S. B. Rapid evolution of sex pheromone-producing enzyme expression in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 7, e1000168. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1000168 (2009).

Mullen, S. P., Millar, J. G., Schal, C. & Shaw, K. L Identification and characterization of cuticular hydrocarbons from a rapid species radiation of Hawaiian swordtailed crickets (Gryllidae: Trigonidiinae: Laupala). J. Chem. Ecol. 34, 198–204 (2008).

Etges, W. J. & Tripodi, A. D. Premating Isolation Is Determined by larval rearing substrates in cactophilic Drosophila mojavensis. VIII. Mating success mediated by epicuticular hydrocarbons within and between isolated populations. J. Evol. Biol. 21, 1641–1652 (2008).

Foley, B., Chenoweth, S. F., Uzhdin, S. V. & Blows, M. W. Natural genetic variation in cuticular hydrocarbon expression in male and female Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 175, 1465–1477 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the faculty and staff of the Natural Sciences Division of the University of Hawaii at Hilo for their support, as well as Karl Magnacca, Curtis Ewing, Christopher Yakym, Renee Corpuz, Matthew Mueller, Eva Brill, Jon Eldon, Kylle Roy, and Joanne Yew. Additionally, we are thankful for the aid of Dominick Skabakeis, Janice Nagata and Lori Carvalho for their assistance in running GC samples.

Funding

National Science Foundation EPSCoR Grant and the National Science Foundation CREST Award to DKP and EAS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.J.F., D.K.P. & E.A.S. conceived the study; T.J.F. & D.K.P. captured Hawaiian Drosophila species from the wild; T.J.F. & D.K.P. raised Drosophila and produced F1 and backcross individuals; T.J.F. & M.S.S. obtained and identified the CHC compounds by GC-MS; E.B.J. provided access to GC-MS and assisted in identifying CHC compounds. T.J.F., D.K.P. & E.A.S. performed statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. M.S.S. & E.B.J. edited the manuscript, and all authors reviewed and approved of the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fezza, T.J., Siderhurst, M.S., Jang, E.B. et al. Phenotypic disruption of cuticular hydrocarbon production in hybrids between sympatric species of Hawaiian picture-wing Drosophila. Sci Rep 12, 4865 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-08635-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-08635-w

This article is cited by

-

High Divergence of Cuticular Hydrocarbons and Hybridization Success in Two Allopatric Seven-Spot Ladybugs

Journal of Chemical Ecology (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.