Abstract

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PDd) is known to suppress the antioxidant system and is likely to aggravate severity of COVID-19, which results in a pro-oxidant response. This possible association has not been explored adequately in human studies. In this research, we report that the occurrence of non-invasive ventilation, intubation or death—all of which are indicative of severe COVID-19, are not significantly different in hospitalized COVID-19 patients with and without G6PDd (4.6 vs. 6.4%, p = 0.33). The likelihood of developing any of these severe outcomes were slightly lower in patients with G6PDd after accounting for age, nationality, presence of comorbidities and drug interventions (Odds ratio 0.40, 95% confidence intervals 0.142, 1.148). Further investigation that extends to both, hospitalized and non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients, is warranted to study this potential association.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PDd) is the most common enzyme deficiency in humans, affecting about 400 million people worldwide, with a high prevalence in persons of African, Asian, and Mediterranean descent1. An X linked disorder, G6PDd is caused by deficiency of Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, a cytosolic enzyme that catalyzes the pentose phosphate shunt. This is required to maintain the level of NADPH, which protects the red blood cells from oxidative injury. Affected patients are usually asymptomatic, but can develop episodic hemolysis following exposure to drug, food or chemicals which can potentiate an oxidative stress on the red blood cells2. G6PDd has been hypothesized to exacerbate severity of SARS-CoV-2 infections, as, the virus prompts a pro-oxidant response while simultaneously suppressing the antioxidant system3. Given that G6PDd results in a compromised antioxidant system, it is postulated that these individuals might suffer more severely from COVID-194. In addition, ex vivo studies show increased vulnerability of G6PD-deficient cells to SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to cells with healthy levels of G6PD5. The most recent observational research involving 182 COVID-19 patients in Sardinia, reported that hospitalized patients had a higher proportion of G6PDd compared those with asymptomatic or mild disease6. There is lack of adequate investigation on G6PDd and severity of COVID-19 clinical outcomes, specifically, whether G6PDd is associated with more severe disease outcomes in humans.. Bahrain has a high prevalence of G6PDd, estimated about 19 to 26.4%7,8,9. Moreover, Bahrain has recorded more than 120,000 COVID-19 cases up to date10. In light of these, the present study aimed to investigate whether G6PDd is associated with severe outcomes in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Results

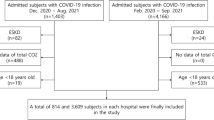

During 24th of February 2020 until 31st of July 2020, a random cohort of 1792 patients was sampled from the COVID-19 patients hospitalized at the participating treatment facilities and enrolled for this study. Out of these, 175 had G6PDd (9.76%). The demographic characteristics and pre-existing comorbidities for patients with and without G6PDd are shown in Table 1. Age distribution was comparable between the two groups; mean age of G6PDd patients being 46.9 ± 16.6 years and that for non-G6PDd being 45.8 ± 17.0 years. Males constituted 53.7% of the G6PDd group compared to 59.6% in the non-G6PDd category (p = 0.14). Diabetes Mellitus, Cardiovascular Disease (CVD), Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and other Chronic Lung Diseases excluding Asthma and COPD were present to a comparable proportion across patients with and without G6PDd. Patients with G6PDd were predominantly Bahraini nationals (91.4% vs. 52.9%) and had higher prevalence of Sickle Cell Disease (9.7% vs, 1.3%), Hypertension (36.6% vs. 29%), Asthma (7.4% vs. 4.1%) and Chronic Kidney Disease (9.7% vs, 3.8%).

The presenting symptomatology in the study subjects was quite varied and has been summarized in Table 2. Almost two thirds of the patients showed some symptoms at admission in both G6PDd and non-G6PDd groups (59.4% and 63.8% respectively), and cough was found to be the most common symptom in both groups (41.1% and 42.1% respectively). It can be seen that both G6PDd and non-G6PDd patients were comparable with respect to the symptoms on admission.

The drug interventions received by the subjects (Table 3) included Azithromycin, Hydroxychloroquine, Ribavirin, Kaletra, Tocilizumab and convalescent plasma. The number of G6PDd and non-G6PDd patients who received these were similar for most treatments except for azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine. Azithromycin was received by higher number of people with G6PDd (33.1% vs. 23.9%). Hydroxychloroquine was used more for people without G6PDd (31.2% vs. 18.9%).

Main outcome in the study included requirement of non-invasive ventilation or mechanical ventilation or death. The proportion of patients who suffered either of these outcomes was similar in G6PDd and non-G6PDd patients and ranged between 2.3 and 3.4% as described in Table 4.

The crude odds ratio of suffering the primary outcome for G6PDd patients was found to be 0.69 (95% CI 0.33, 1.45), as shown in Table 5. After adjusting for age, nationality, comorbidities (HTN, CKD, COPD, SCD) and drug interventions, the OR decreased slightly to 0.403 (0.142, 1.148), but remained statistically non-significant (p = 0.132, Supplementary Table S1). We also evaluated whether the co-presence of G6PDd and SCD had differential effect on the outcome, by testing for effect measure modification (Supplementary Table S2). SCD and G6PD did not appear to modify each other’s effect on the primary outcome (p = 0.92).

Discussion

The present study did not find hospitalized patients with G6PDd to have higher odds of requiring NIV, HFNC, MIV or death, after accounting for age, nationality, drug interventions and comorbidities (HTN, COPD, CKD SCD).

The patients in both G6PDd and non-G6PDd group were comparable in terms of age and sex. Our cohort was considerably younger with a mean age 45.9 years, compared to hospitalized patients in United States11,12 (median age 65 years) and United Kingdom13 (mean age of 70.5 years). The G6PDd groups was predominantly Bahraini nationals as compared to other nationalities, which is not surprising given that the prevalence of G6PDd has been reported to be highly prevalent in the native population of Bahrain from 19 to 26.4%7,8,9 and to the extent of 47% in those with sickle cell trait8. Owing to the same phenomenon, the occurrence of SCD was significantly high in the G6PDd group (9.7%) compared to the non-G6PD group (1.3%). Given recent studies on SCD and risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes14,15,16, we evaluated whether the copresence of SCD and G6PD would affect the outcome by looking at presence of effect measure modification of SCD on the G6PDd and the primary outcome. The result showed that SCD didn’t alter the risk of the primary outcome in G6PDd patients (Supplementary Table S2).

The medications used in this cohort should be interpreted with the study timeline. Early in the pandemic HCQ and Azithromycin received wide attention in its use in COVID19 patients17. Similarly, Kaletra and Ribavirin in were also used18,19,20. Hence, it was common to prescribe these drugs in hospital settings at that time. Moreover, the use of antibiotics was common in patients with pneumonia. As more evidence about the lack of benefit from these drugs and the potential harm was released, the use of these medications has decreased21,22,23,24,25,26. The benefit of steroids in hypoxic COVID19 patients was reported in June26 and it was only after that that steroids were used in hospitalized patients.

HCQ is known to increase risk of acute hemolysis in G6PDd patients and hence it is relatively contraindicated in G6PDd patients. This have led to the reduced use of HCQ in G6PDd patients. On the other hand, Azithromycin was used more commonly in G6PDd patients as the use of HCQ was limited. This has caused more patients in the G6PDd group to receive Azithromycin. The combination between the two drugs have been linked to increased risk of arrythmia, QT prolongation and this could explain the lower use of combination between HCQ and Azithromycin in the non G6PDd patients27.

G6PDd group was relatively worse compared to non-G6PDd counterparts with respect to presence of HTN, Asthma and CKD. Meta-analyses have reported HTN to confer a two-fold increase in hazards of mortality (adjusted HR 2.12; 95% CI 1.17, 3.82)28,29, while asthma being a respiratory condition is highly associated with worse outcomes in COVID-19 patients with an RR of 1.96; 95% CI 0.89, 4.3330. In addition, CKD has been reported to result doubling of the risk of mortality (RR: 2.11; 95% CI 1.72, 2.58) in hospitalized patients30. The higher prevalence of these conditions in G6PDd patients kept them at a higher baseline risk to develop worse disease outcomes.

The occurrence of CVD, DM and other Chronic Lung Diseases was not affected by G6PDd status. Diabetes has been established to be a one of the key risk factors severe COVID-19 outcomes and is significantly associated with death or tracheal intubation with 7 days of hospitalization31. Prospective studies have reported a two-fold increase in odds of death with CVD (OR 2.46; 95% CI 0.755, 8.044)28. Since both these major comorbidities were equally present in both patients with and without G6PD, it is likely that the risk of outcome attributable to these comorbidities would have been apportioned between the groups.

Patients had similar profile and range of presenting symptoms across the G6PDd and non-G6PDd groups with no significant differences. However, it is worth noting that the non-G6PDd group had marginally higher occurrence of symptoms (63.8%) compared to G6PD (59.4%). In addition, relatively larger proportion of the non-G6PDd required mechanical ventilation, non-invasive ventilation as well as oxygenation upon admission and hence, seemed to be worse off compared to the G6PDd group. One of the reasons for this could be that the G6PDd patients could have had a lower admission threshold because of presence of G6PDd and were perceived to be at a higher risk. This could be especially true given G6PDd deficient patients had significantly higher proportion of high-risk comorbidities of SCD, HTN, Asthma and CKD, as well as marginally higher occurrence of CVD.

Initially during the pandemic in Bahrain, patients with risk factors were admitted to hospitals even if they had mild disease. As opposed to cases without risk factors, who were hospitalized based on a clinical decision. Risk factors for severe COVID 19 included: Older Age, Smoking, Obesity, DM, CVD, Respiratory diseases and lung cancers32,33,34.

Patients in the G6PDd group were older on baseline and had more of these risk factors, namely CVD HTN and CKD. This has led to a lower hospitalization threshold for the G6PDd patients. This is also reflected upon the severity of disease in both groups. The G6PDd group were less symptomatic and none required advanced oxygenation on admission to the hospital, as most were admitted early during their disease course. Therefore, more patients with G6PDd were hospitalized when compared to non G6PDd patients. Patients who were in home isolation were not studied in this research and hence the outcomes of G6PDd on a population level could not be measured. Owing to these reasons, milder cases of COVID-19 in G6PDd were disproportionately high in this cohort. This has the potential to bias the results towards the null.

One of the main strengths of this study lies in the inclusion of majority of the national tertiary care hospitals that provided care for hospitalized COVID-19 patients. The fact that data collection from the EMR was done manually, reviewed and checked by the study authors and contributors, speaks to the quality of the data. The present study represents the only available research in Bahrain that looks at the role of G6PDd and COVID-19 outcomes.

Our study is restricted to hospitalized COVID-19 patients and therefore it is not possible to generalize the results to COVID-19 cases in the outpatient setting. Due to the same reason, it is not possible to infer the effect of G6PDd on COVID-19 symptomatology in milder cases that did not require hospitalization. Given the data was obtained from EMR, it is possible that the lifestyle factors not captured in EMR such as smoking and obesity, could not be accounted for in the analysis and could be potential confounders. In addition, time from symptom onset, inflammatory markers and frequency of G6PDd related admissions patients were also not captured in the EMR and could be source of unmeasured confounding.

In conclusion, the present study did not find any association between presence of G6PDd and occurrence of serious outcomes in COVID-19 patients. We recommend further large-scale studies that include both hospitalized and non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients, for a more comprehensive insight on the role of G6PDd the pathophysiology of COVID-19 outcomes.

Methods

Study population, patient selection and data extraction

The study population consisted of COVID-19 cases that were admitted at Bahrain Ministry of Health COVID-19 treatment facilities between 24 February to 31 July 2020. The four participating COVID-19 treatment facilities included Ebrahim bin Khalil Kanoo COVID-19 Centre, Salmaniya Medical Complex COVID-19 Centre, Hereditary Blood Disorder Centre (HBDC) COVID-19 Centre and Jidhafs COVID-19 Centre. Data on these patients was obtained from the electronic medical record (EMR) system, “I-SEHA”, which contains patient records and clinical information as text files. Patients with and without G6PDd were sampled randomly. Patients were included if they were above 18 years of age, had a diagnosis of COVID-19 disease and were admitted between the above specified dates. Data was extracted manually from EMR by five physicians and ten senior medical students, who reviewed all the cases and filled an electronic patient record form developed to collect data for this study.

Diagnosis of COVID-19

All patients were confirmed to be infected by SARS-CoV-2 by a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test of a nasopharyngeal sample. The PCR test was conducted using Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA) TaqPath 1-Step RT-qPCR Master Mix, CG on the Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA) 7500 Fast Dx RealTime PCR Instrument. The assay used and targeted the E gene. If the E gene was detected, the sample was then confirmed by RdRP and N genes. The E gene Ct value was reported and used in this study. Ct values > 40 were considered negative. Positive and negative controls were included for quality control purposes.

Exposure assessment

The exposure of interest was presence of G6PDd, information on which was obtained from the medical records. The original diagnosis of G6PDd was made through fluorescence spot test using whole blood. Patients with intermediate levels of G6PD were not considered as having the exposure of interest.

Outcome assessment

Primary outcome in this study was a composite endpoint that included either requirement of non-invasive ventilation, intubation or death.

Covariates

Information was collected on patients’ demographic details, vital signs, laboratory test results, medication lists, past medical history, clinical severity scale (as seen in the Supplementary Table attached in the appendix), oxygenation requirement on admission, the ratio of the oxygen saturation to the fraction of inspired oxygen (SpO2:FiO2) at admission, requirement of ICU care, ventilator use and outcomes. A complete list of variables collected is attached in Appendix A.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables have been described using frequencies and percentages and continuous variables, as means and standard deviations. Bivariate associations between the G6PDd status groups and the measured patient characteristics have been analyzed using Chi-squared (χ2) tests for categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables. A multi-variable logistic regression model was used to estimate the association between G6PDd and the primary and secondary outcomes. The primary outcome model adjusted for demographic factors, clinical factors and medications. Effect modification was analyzed using interaction term in a regression model. All analyses were performed using STATA software, version 16, (StataCorp. 2019. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol and manuscript for this study were reviewed and approved by the National COVID-19 Research Committee in Bahrain (Approval Code: CRT-COVID2020-061). This committee has been jointly established by the Ministry of Health and Bahrain Defense Force Hospital research committees in response to the pandemic, to facilitate and monitor COVID-19 research in Bahrain. All methods and retrospective analysis of data was approved by the National COVID-19 Research and Ethics Committee and carried out in accordance with the local guideline and ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki 1975. All data used in this study was collected as part of normal medical procedures. Informed consent was waived by the National COVID-19 Research and Ethics Committee for this study due to its retrospective and observational nature and the absence of any patient identifying information.

Data availability

Original data will be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Luzzatto, L., Ally, M. & Notaro, R. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Blood 136(11), 1225–1240. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019000944 (2020).

Nkhoma, E. T., Poole, C., Vannappagari, V., Hall, S. A. & Beutler, E. The global prevalence of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 42(3), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcmd.2008.12.005 (2009).

Yang, H. C., Ma, T. H., Tjong, W. Y., Stern, A. & Chiu, D. T. G6PD deficiency, redox homeostasis, and viral infections: implications for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Free Radic. Res. 24, 1–1 (2020).

Buinitskaya, Y., Gurinovich, R., Wlodaver, C. G. & Kastsiuchenka, S. Centrality of G6PD in COVID-19: the biochemical rationale and clinical implications. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 7, 584112. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.584112 (2020).

Wu, Y. H. et al. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency enhances human coronavirus 229E infection. J. Infect. Dis. 197(6), 812–816. https://doi.org/10.1086/528377 (2008).

Littera, R. et al. Human leukocyte antigen complex and other immunogenetic and clinical factors influence susceptibility or protection to SARS-CoV-2 infection and severity of the disease course. The Sardinian experience. Front. Immunol. 4(11), 3320 (2020).

Al, A. S. Frequency of G6PD deficiency among Bahraini students: A ten years’ study. Bahrain Med. Bull. 32(1), 18–21 (2010).

Mohammad, A. M., Ardatl, K. O. & Bajakian, K. M. Sickle cell disease in Bahrain: coexistence and interaction with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency. J. Trop. Pediatr. 44(2), 70–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/44.2.70 (1998).

Bhagwat, G. P. & Bapat, J. P. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in Bahraini blood donors. Bahrain Med. Bull. 9(3), 120–122 (1987).

The official website for the latest health developments, Kingdom of Bahrain. https://healthalert.gov.bh/en/category/daily-covid-19-report. Accessed 22 Dec 2020 (2020).

Garg, S. et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019—COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 69, 458–464. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3 (2020).

Richardson, S. et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA 323, 2052 (2020).

Alkundi, A., Mahmoud, I., Musa, A., Naveed, S. & Alshawwaf, M. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 hospitalized patients with diabetes in the United Kingdom: A retrospective single centre study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 165, 108263 (2020).

Abdulrahman, A. et al. Is sickle cell disease a risk factor for severe COVID-19: a multicenter national retrospective cohort. eJHAEM https://doi.org/10.1002/jha2.170 (2021).

Panepinto, J. A. et al. Coronavirus disease among persons with sickle cell disease, United States, March 20–May 21, 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 26(10), 2473 (2020).

Cariou, B. et al. Phenotypic characteristics and prognosis of inpatients with COVID-19 and diabetes: the CORONADO study. Diabetologia 63(8), 1500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-020-05180-x (2020).

Chu, C. M. et al. Role of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: initial virological and clinical findings. Thorax 59, 252–256 (2004).

Spanakis, N. et al. Virological and serological analysis of a recent Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection case on a triple combination antiviral regimen. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 44, 528–532 (2014).

Omrani, A. S. et al. Ribavirin and interferon alfa-2a for severe Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 14, 1090–1095. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70920-X (2014).

Horby, P. et al. Effect of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 1, 2 (2020).

Abdulrahman, A. et al. The efficacy and safety of hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID-19: a multicenter national retrospective cohort. Infect. Dis. Ther. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-021-00397-8 (2021).

Cao, B. et al. A trial of lopinavir–ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1787–1799 (2020).

Horby, P. W. et al. Lopinavir–ritonavir in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet 396(10259), 1345–1352 (2020).

Abaleke, E. et al. Azithromycin in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet 397, 605–612 (2021).

Tong, S. et al. Ribavirin therapy for severe COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 56(3), 106114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106114 (2020).

RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19—preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 693–704 (2020).

Rosenberg, E. S. et al. Association of treatment with hydroxychloroquine or azithromycin with in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 in New York State. JAMA 323(24), 2493–2502 (2020).

Gao, C. et al. Association of hypertension and antihypertensive treatment with COVID-19 mortality: A retrospective observational study. Eur. Heart J. 41(22), 2058–2066. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa433 (2020).

Noor, F. M. & Islam, M. M. Prevalence and associated risk factors of mortality among COVID-19 patients: A meta-analysis. J. Commun. Health 45(6), 1270–1282 (2020).

Gautret, P. et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: Results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 56(1), 105949 (2020).

Du, R. H. et al. Predictors of mortality for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2: A prospective cohort study. Eur. Respir. J. 55(5), 2000524. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00524-2020 (2020).

Simonnet, A. et al. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22831 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Associations of hypertension with the severity and fatality of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a meta-analysis. Epidemiol. Infect. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095026882000117X (2020).

Williamson, E. J. et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 584, 430–436. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the Bahrain National COVID-19 Taskforce for making this study possible and to RCSI Bahrain for publication funding support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.K. analyzed, interpreted the data and prepared the manuscript; A.A. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript; A.I.A. oversaw the data collection and entry; M.A.Q. was responsible for conception and design of the study and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, N., AbdulRahman, A., AlAwadhi, A.I. et al. Is glucose-6-phosphatase dehydrogenase deficiency associated with severe outcomes in hospitalized COVID-19 patients?. Sci Rep 11, 19213 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-98712-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-98712-3

This article is cited by

-

G6PD deficiency—does it alter the course of COVID-19 infections?

Annals of Hematology (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.