Abstract

Post-harvest storage of grains is crucial for food and feed reserves and facilitating seeds for planting. Ironically, post-harvest losses continue to be a major food security threat in the developing world, especially where jute bags are utilized. While jute fabrics flaunt mechanical strength and eco-friendliness, their water-loving nature has proven to be their Achilles heel. Increased relative humidity and/or precipitation wets jute, thereby elevating the moisture content of stored seeds and causing fungal growth. This reduces seed longevity, viability, and nutritional value. To address this crucial weakness of jute bags, we followed a nature-inspired approach to modify their surface microtexture and chemical make-up via alkali and wax treatments, respectively. The resulting wax-coated jute bags (WCJBs) exhibited significant water-repellency to simulated rainfall and airborne moisture compared to control jute bags (CJBs). A 2 months-long seed storage experiment with wheat (Triticum aestivum) grains exposed to 55%, 75%, and 98% relative humidity environments revealed that the grains stored in the WCJBs exhibited 7.5–4% lesser (absolute) moisture content than those in the CJBs. Furthermore, WCJBs-stored grains exhibited a 35–12% enhancement in their germination efficacy over the controls. This nature-inspired engineering solution could contribute towards reducing post-harvest losses in the developing world, where jute bags are extensively utilized for grain storage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2020, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the World Food Programme, underscoring that some fractions of humanity are still deprived of food security1. According to the United Nation’s Food and Agricultural Organization, developing sustainable agricultural practices to feed ~ 1010 humans in 2050 will be a mega-challenge of our lifetime; it is anticipated that annual food production worldwide must increase by approximately 70%2,3,4,5. At present, grain crops such as cereals, oilseeds, and pulses, which form the basis of global food security6,7,8, are produced at the scale of ~ 2 B tons/year7,9. By 2050, this is projected to increase by > 33%3,10. However, increasing crop yields beyond current levels is likely to be difficult due to climate change, groundwater depletion and pollution, and limited energy resources11,12,13,14. Food security in the emerging scenario will mandate a highly efficient supply chain from farm to consumer8.

Currently, post-harvest losses (PHLs), which entail quantitative and qualitative losses from harvest through to storage, processing, marketing, and consumption, claim 25–33% of the entire grains produced globally6,15,16,17,18. In developed countries, grain losses during storage can be as low as 1–2% because of the application of modern technologies9,19. In developing countries, contrastingly, up to 60% of cereals may be lost during storage due to poor storage infrastructure16,17,18,20, slower adoption of modern technologies21, and fragmented information sharing19. PHLs can be in the form of spoilage, seed viability loss, grain depletion, and nutritional loss22 resulting from biotic (e.g., insects, rodents, and fungi) or abiotic (e.g., temperature and air-moisture/humidity) factors9. Fungal infections account for 25–40% of PHLs23,24, and mycotoxin contamination can pose a significant health risk25.

Airborne water vapor (mass/volume)—commonly expressed as relative humidity (RH: the ratio of the partial pressure of water vapor to the saturation vapor pressure at a given temperature)—crucially influences the equilibrium seed moisture content (SMC); the specifics of water uptake vary with seed type and temperature26,27. Elevated SMC promotes the growth of bacteria, fungi, and insects and vice versa. For example, storage at 30 °C below 65% RH corresponds to an equilibrium SMC of 12–14% in cereals, which prevents fungal infestation15,27,28; on the other hand, storage at < 35% RH (or < 8% SMC)27,28,29 arrests the growth of insects on top of fungi. In contrast, at RH > 65%, as SMC exceeds 14%, storage bacteria, fungi, and insects start respiring and increasing temperature and deteriorating grains15,30,31. For example, the germination capacity of soybean (Glycine max), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), red clover (Trifolium pratense), and Timothy grass (Phleum pratense) seeds reduced substantially during 6–12 months of storage at 30 °C and 75% RH32. In this context, Harrington’s thumb rule states that for every 1% increase in SMC, shelf life decreases by 50%30,31,33,34,35; this exponential relationship underscores the role of storage bags in acting as a diffusion barrier for water vapor.

To keep SMC under check, the concept of “dry chain”—akin to “cold chain” for perishable products—has been put forth, wherein grains are dried upon harvest followed by the use of moisture-proof packaging until consumption28,36. Furthermore, to combat humid environments, researchers have developed moisture- and oxygen-proof hermetic storage systems such as GrainPro Superbags™ and Purdue Improved Crop Storage (PICS) bags28,36,37,38,39,40. However, these polypropylene bags are vulnerable to puncturing from sharp objects and rodents; cost and disposal also prevent widespread adoption. Therefore, low-cost solutions for preventing PHLs are still needed.

In the Indian subcontinent and sub-Saharan Africa, farmers exploit jute bags for grain storage because of their low cost, mechanical durability, and traditional usage over millennia9,21,41. These bags are stacked in traditional storage structures or outdoor stockpiles covered with tarpaulin9,21. Jute is water-loving (hydrophilic) in nature; and it also absorbs water due to its constituents—cellulose (~ 60%), hemicellulose (~ 20%), lignin (~ 10%), pectin, and water-soluble substances42,43,44,45. Stored grains are often exposed to high humidity, especially in the event of precipitation or increased RH, which wets the bags and elevates SMC, accelerates seed deterioration, and reduces germination efficacy28,32,46. In India, for example, nearly 60–70% of all the grains produced are stored in conventional structures of which ~ 35% of rice and wheat grains get damaged by PHLs47.

To address this weakness of jute bags, we took inspiration from nature—the various plants and animals that have evolved water-repellency by combining hydrophobic waxy coatings with micro/nanoscale surface roughness. Examples include lotus leaves (Nelumbo nucifera)48, bodies of sea-skaters (Halobates germanus)49, cuticles of springtails (Collembola)50, as well as certain desert plants51 and insects52, among others53. In this work, jute fabrics were treated with alkalis to induce surface roughness, followed by coating with paraffin wax to engender water repellency. The seed storage efficacy of these wax-coated jute bags (WCJBs) was then compared with that of control jute bags (CJBs, i.e., untreated jute bags) under specific relative humidity conditions over a 2-months-long storage duration. This was followed by a germination study in which the viability of seeds stored in WCJBs and CJBs was comparatively assessed.

Results

Water repellency

Our study demonstrates a simple surface treatment protocol to produce hydrophobic WCJBs through chemical treatment with alkali, followed by surface coating using paraffin wax that is inexpensive and readily available (Fig. 1).

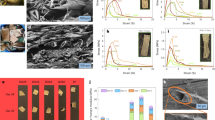

After wax coating, the characterization of jute surface morphologies using SEM revealed a smooth fiber surface in the CJBs while WCJBs appeared rougher (Fig. 2). Gaps between WCJB fibers (Fig. 2D–F) reduced in comparison to those between CJB fibers (Fig. 2A–C) because wax coating tends to bind adjacent fibers. In addition, following the alkali treatment and wax coating, fibers of WCJBs appeared swollen (Fig. 2D) than of CJBs (Fig. 2A).

When water droplets of ~ 8 μL were placed onto CJBs, they gradually penetrated into the fibers in ≤ 2 min (Fig. 3A,C,E), while WCJBs significantly repelled water droplets as demonstrated by water droplets failing to penetrate even after > 3 h during which they evaporated (Fig. 3B,D,F). Furthermore, when CJBs and WCJBs were exposed to simulated rainfall, the CJBs got wet by impacting water droplets that they accumulated (Movie 1). In contrast, water droplets simply rolled-off the WCJBs on impact, thereby preventing water accumulation (Movie 2).

Representative photographs showing time-dependent wetting of control jute bags (CJBs) and wax-coated jute bags (WCJBs). At 30 s, water droplets began to seep into the CJBs, whereas droplets could not penetrate into the WCJBs (A,B). Within 1 min, CJBs showed significant wetting; in contrast, water droplets did not spread on the WCJBs (C,D). From 2 min onwards, water droplets were completely absorbed by the CJBs, whereas the droplets on WCJBs could not penetrate even after > 3 h (E,F). (Note: we added dye to color the water in order to serve as a visual aid; experiments without dye yielded identical results).

Seed storage experiments

After comparing the wetting behaviors, we hypothesized that WCJBs should have superior potential for protecting stored grains from humidity than CJBs. Wheat (T. aestivum) grains were stored for 2 months in WCJBs and CJBs (controls) at 21.6 ± 0.5 °C under three different relative humidity conditions: 55%, 75%, and 98%. The SMC of the wheat prior to storage was 7.1%. During the study, we quantified changes in the mass of the storage bags containing grains every 3 days and also looked for signs of moisture accumulation on the bags, dampness, and fungal (mold) growth (Figs. 4, Fig. S1).

Moisture absorption through jute bags and the moisture content of wheat grains after 2 months of storage. (A) Total moisture absorbed through control jute bags (CJBs: unfilled shapes) and wax-coated jute bags (WCJBs: filled shapes) over the seed-storage period. Total moisture absorbed was taken as the sum of moisture uptake by jute bags and stored grains; the combined mean mass of the storage bag plus seed was ~ 170 g/bag. (B) Post-storage seed moisture content (SMC) of stored wheat grains at different relative humidity (RH) conditions. Horizontally-dotted line (SMC0) represents initial SMC (7.1%) before storage; error bars represent the standard errors (± SE) of means from three replicates.

Seed moisture content

For the 55% RH treatment, the total moisture absorbed by the WCJB + grain system was 46% lower than that of the CJB + grain system (Fig. 4A); the SMC of the grains stored in the WCJBs increased from 7.1 to 7.5%, whereas the SMC of the grains in the CJBs increased from 7.1 to 14.9% (Fig. 4B). Crucially, CJBs absorbed 12-times more moisture than that absorbed by WCJBs; thus, they acted as reservoirs for moisture influx into stored grains. Next, for the 75% RH treatment, the total moisture absorbed by the WCJB + grain system was 32% lower than the controls; the SMC of the grains stored in the WCJBs increased from 7.1 to 11%, whereas the SMC of the grains in the CJBs increased to 17%. Lastly, for the 98% RH treatment, the total moisture absorbed by the WCJB + grain system was 45% lower than the controls; the SMC of the grains stored in the WCJBs increased to 26%, whereas the controls increased to 32%. These findings demonstrate that WCJBs provide superior protection to stored grains than CJBs at \(\le\) 75% RH.

Fungal infestation

Due to their water repellency, WCJBs absorbed significantly lesser water than CJBs from the air during storage under different RH conditions. For the 55% RH treatment, we did not observe signs of fungal mold on bags or grains in WCJBs or CJBs (Fig. 5A,D). For the 75% RH treatment, the WCJBs and stored grains did not exhibit mold growth, whereas the CJBs and stored grains showed dampness and fungal growth towards the end of the study (Fig. 5B,E). Tiny droplets of condensed water appeared onto WCJBs towards the end of the study, as expected for hydrophobic surfaces but the droplets did not imbibe into the bag's surface54. For the 98% RH treatment, both WCJBs and CJBs and stored grains exhibited dampness and fungal growth (Fig. 5C,F). Condensed water droplets appeared on WCJBs after 2 weeks (Fig. 5F inset), and as they grew larger, many rolled off the surface. Fungal proliferation on the grains stored inside WCJBs was less prominent than that on the grains stored inside CJBs.

Photographs of wax-coated jute bags (WCJBs) and control jute bags (CJBs) with stored wheat grains after 8 weeks of storage under different relative humidity (RH) conditions. CJBs with wheat grains at 55% RH (A), 75% RH (B), and 98% RH (C); WCJBs and wheat grains stored at 55% RH (D), 75 % RH (E), and 98% RH (F). Red arrows indicate fungal (mold) growth. At 55% RH, neither WCJBs nor CJBs suffered from dampness or fungal growth, although seed moisture content increased from 7.1% to 7.5% in WCJBs and 14.9% in CJBs. WCJBs also performed well at 75% RH; however, grains stored in CJBs at 75% RH showed signs of fungal growth. At 98% RH, both WCJBs and CJBs and their stored grains exhibited dampness and fungal growth (dark grey patches). The inset photograph in (F) shows the accumulation of moisture on WCJBs in the third week of storage.

Seed germination efficacy

To further explore the effects of storage on seed health after our 2 months-long study, we investigated seed germination efficacy using the following formula:

In a 1 week-long study of germination (Fig. 6A), we found that grains stored in WCJBs performed better than those stored in CJBs (p < 0.05). For 55%, 75%, and 98% RH conditions, WCJBs afforded 32%, 35%, and 12% higher germination efficacy, respectively (Fig. 6B).

Seed germination on Petri dishes of wheat grains stored for 8 weeks in control jute bags (CJBs) and wax-coated jute bags (WCJBs) under different relative humidity (RH) conditions. (A) Seed germination patterns monitored for 7 days after sowing and (B) germination of seeds stored in control jute bags and WCJBs at 55%, 75%, and 98% RH. The percentage seed germination of wheat grains stored in WCJBs was higher than that of wheat grains stored in CJBs under all RHs. Error bars represent the standard error (± SE) of means from 90 seeds/treatment.

Discussion

Here we discuss the factors and mechanisms underlying the superior performance of WCJBs at safeguarding grains and seed germination efficacy. First, we discuss the effects of alkali and wax treatments on jute surface properties. Alkali treatment of cellulosic fibers, also known as mercerization, has been exploited to tune various fiber characteristics, such as elastic moduli, brittleness, surface roughness, and readiness for surface coating, of jute and cotton44,55,56,57,58. It dissolves hemicellulose and other fiber components causing swelling and constriction of pores in jute fabrics44,59,60,61. Researchers have demonstrated that mechanical properties such as tensile strength, flexural strength, tensile modulus, and flexural modulus are superior for 6% NaOH-treated jute fabric reinforced composites relative to the jute fabrics treated at higher alkali concentrations (> 6%)62. Therefore, we chose alkali concentration of 5% and treatment duration of 2 h to enhance surface roughness without significantly depleting mechanical strength44,59,63.

As alkali-treated jute fabrics were coated with paraffin wax, the combination of surface roughness and the hydrophobicity of the wax produced robust water repellency64. The intrinsic hydrophobicity of paraffin wax is characterized by the apparent contact angles of water droplets on smooth wax-coated surfaces: \({\theta }_{o}\approx 105^\circ\) 65. When a rough surface is coated with a hydrophobic coating, the resulting water-repellency is enhanced by the entrapment of air inside the surface asperities, which also prevent the penetration of water into the microtexture66. While water droplets rapidly penetrated the CJBs, water droplets placed onto WCJBs did not penetrate into the fibers due to the entrapment of air in the microtexture. Apparent contact angles of water drops were \({\theta }_{\mathrm{r}}\approx {130}^{^\circ }\) and they remained pinned as they evaporated (Fig. 3B,D,F). These air-trapped wetting states are described by the Cassie–Baxter model, which connects the macroscopic apparent contact angles on the rough surface, \({\theta }_{\mathrm{r}}\), with \({\theta }_{\mathrm{o}}\) and the area fractions of liquid–solid (\({\phi }_{\mathrm{L}\mathrm{S}}\)) and liquid–vapor (\({\phi }_{\mathrm{L}\mathrm{V}}\)) fractions underneath the drop as \(\mathrm{cos}{\theta }_{\mathrm{r}}={\phi }_{\mathrm{L}\mathrm{S}}\times \mathrm{cos}{\theta }_{o}-{\phi }_{\mathrm{L}\mathrm{V}}\)67. If the impacting droplets have momentum, they even bounce off the surface68. Therefore, WCJBs are not as vulnerable to precipitation as CJBs (Fig. 7).

Schematic showing the surface treatments of jute bags with alkali and wax coating, the seed storage experiment, and the germination experiment for stored wheat grains. Control jute bags, CJBs; hydrophobic (wax-coated) jute bags, WCJBs. While CJBs accumulate water and get wet, WCJBs prevent water accumulation and cause water droplets to roll off their surface. Post-storage seeds from WCJBs are more likely to have higher germination than seeds from CJBs (image credits: Xavier Pita, KAUST).

Water condensing on CJBs surface is expected to form thick films due to jute’s hydrophilicity54. Thus, CJBs appeared damp in the storage experiments and acted as reservoirs for moisture for the seeds stored inside. In contrast, water condensed as discrete droplets on WCJBs due to their hydrophobicity. As these droplets grew larger over time or due to coalescence, many of them rolled off as their weight approached the magnitude of pinning forces, which reduced the effect on the SMC of stored grains.

We also noticed that the fibers of WCJBs were somewhat swollen in contrast to those of CJBs (Fig. 2). This likely led to partial pore clogging of the treated-jute layer and reduced the flux of water vapor through the pores69. Additionally, paraffin wax seeping through pores from both surfaces could have further constricted the pores. This hypothesis is consistent with previous findings, where the durability of jute geotextiles was studied in soil, and the authors noticed that impregnation of nonwoven jute samples with bitumen reduced jute pore sizes because of the formation of a superimposing bitumen binder layer on the surface of both sides of the jute fabric70.

Lastly, we note that the differences in the SMC of wheat grains stored in WCJBs and CJBs were quite large, but this did not translate into exponential trends in germination efficacy as expected by Harrington’s thumb rule. This was presumably due to the short duration of our storage experiment, i.e., fungal infestation did not severely deteriorate the stored seeds. Thus, experiments with longer storage duration are warranted to probe this further.

Conclusion

Principles underlying water repellency in various animals and plants have been harnessed for developing technologies for separation and purification64,71, desalination72,73,74, cavitation mitigation75, coating-free entrapment of air underwater50,76,77, and producing super-water-repellent cotton56, among others65. However, their application in agricultural engineering and technology has remained limited78,79. This proof-of-concept study demonstrates that WCJBs can substantially extend the shelf life and germination efficacy of seeds stored under low RH conditions and facilitate increased resilience under higher RH conditions. We hope that these results will inspire multidisciplinary research towards identifying strengths and weaknesses of this approach. Many questions remain unanswered such as: How SMC and seed germination efficacy vary over longer experimental duration and with seed type?; How to dispose/recycle WCJBs?; Would wax coatings degrade during handling/transportation?; What is the simplest process for applying wax on jute fabrics?; How does the cost of WCJBs compare with alternatives, such as PICS? Life cycle analysis of wax-coated jute and its other water-proofing applications should also be explored. We hope that this nature-inspired approach can help us realize jute’s full potential for grain storage and beyond.

Methods

Materials and apparatus

Paraffin wax was obtained from common white candles manufactured by IKEA (Sweden); hexane and ethanol were purchased from VWR International S.A.S (Fontenay-Sous-Bois, France); ammonium acetate, glacial acetic acid, and calcium nitrate tetrahydrate (Ca(NO3)2·4H2O)) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA); sodium chloride, potassium sulfate, and sodium hydroxide were purchased from Fisher Scientific (New Jersey, USA). All chemicals were used as received from suppliers. Jute packaging sacks (Indian Sela Basmati Rice, 50 kg) were obtained from the Al Jawahir Company (Saudi Arabia). A Quanta 600 scanning electron microscope system was used for scanning electron microscopy. A Quorum Q150 TS sputter coater was used to coat jute bags (CJBs and WCJBs) with a 3 nm-thick platinum layer to avoid electrical charging during electron microscopy. A DSA100E contact angle goniometer (Kruss, Germany) was used to characterize the wettability of surfaces. Wheat grains (Triticum aestivum L.) were harvested from a field at King Abdulaziz University’s Agricultural Research Station in Hada Al-Sham (which extends between 39° 30′ and 40° 15′ East and 21° 45′ and 22° 10′ North, in Makkah, Saudi Arabia).

Surface treatment of jute

Jute sacks (fabric thickness ~ 11.28 ± 0.06 mm) were cut into 12.6 cm × 10.5 cm pieces and hand-sewn to produce jute storage bags (483 ± 97 g/bag). First, the bags were cleaned by immersion in water (10 min) and then 70% ethanol (20 min), before being dried in a thermal convection oven at 80 °C (30 min). Cleaned bags were then immersed in 0.5-M ammonium acetate solution (adjusted to pH 5 using 1.0% glacial acetic acid) for 30 min. After further oven drying at 80 °C (30 min), the bags were immersed in 5% (m/v) NaOH solution (1.25 M and pH ~ 14) for 2 h. These alkali-treated bags were washed with deionized water and again oven-dried at 80 °C (30 min). Subsequently, the bags were immersed in solutions of paraffin wax dissolved in hexane (6 g/L), during which they were turned upside-down several times to facilitate uniform coating. After 30 min of this treatment, the bags had absorbed ~ 100 mL of the wax solution and were left to dry overnight in a solvent hood at 21.6 °C ± 0.5 °C.

Wettability tests

Deionized water droplets with and without food coloring and the DSA100E contact angle goniometer were used to characterize the wettability of bag surfaces. WCJBs and CJBs were also exposed to simulated rainfall for ~ 1 min: they were placed at an angle of ~ 30° and the simulated raindrops were applied by releasing water droplets (~ 2 mL) from a syringe placed ~ 5 cm above the bags. The moisture absorption of WCJBs and CJBs was estimated by measuring their mass.

Seed storage experiments

Clean and healthy wheat (T. aestivum) grains, devoid of any physical damage, were selected and placed inside paper bags for initial weight measurement. These grains were then dried in an oven at 80 °C for 72 h, after which their mass did not change further; thus, SMC in the initial state was calculated as follows: \(SMC=({W}_{1}-{W}_{2})/{W}_{1}\), where \({W}_{1}\) is the initial weight of grains and \({W}_{2}\) is their final weight after drying. Subsequently, wheat grains were packaged in WCJBs and CJBs, and the bags were placed in airtight plastic containers with the following RHs: 55%, 75%, and 98%. The air humidity level was controlled in confined spaces by equilibrating it with supersaturated salt solutions of Ca(NO3)2·4H2O, NaCl, and K2SO480,81. Specifically, to obtain 55% RH, 50 g of Ca(NO3)2·4H2O was dissolved in 100 mL of deionized water by stirring; more salt was added until a saturated solution was formed with a salt:water ratio of 3:1 (w/w). This procedure was repeated to obtain 75% RH using NaCl (but with a 2:1 salt:water ratio) and 98% RH using K2SO4 (at a ~ 3:1 salt:water ratio). The saturated salt solutions were then poured into the lower compartment of the airtight plastic containers, which were integrated with humidity and temperature sensors (Fig. S1). The bags containing wheat grains were then placed on a plastic mesh tray (barrier) above the saturated salt solutions; therefore, they were exposed to air with well-controlled humidity. Experiments were carried out in triplicate; therefore, nine containers with WCJBs or CJBs were randomly placed and monitored for 2 months. Moisture absorption was determined by weighing each jute bag every 3 days. Total moisture absorbed was calculated in grams per gram of jute bag plus stored seed combined.

Seed moisture content and post-storage germination/viability

After 2 months of seed storage, grains from each bag was thoroughly homogenized and ~ 130 g of seed sub-sample was randomly withdrawn from each bag and put into paper bags, weighed, and then oven-dried at 80 °C for 72 h to determine post-storage SMC. To evaluate the germination efficacy of post-storage seeds, 30 grains from each storage bag were germinated in Petri dishes containing Whatman filter paper soaked in deionized water. These dishes were maintained in a dark incubator and allowed to germinate at 21.6 ± 0.5 °C. The germination patterns of seeds were monitored from the first day after sowing until the seventh day, after which the experiment was discontinued.

Statistical analysis

The seed storage experiment involved a completely randomized factorial design, which was used to investigate the effect of jute storage bags and RH on moisture absorption, SMC, and seed germination percentage. For analysis of data including triplicate samples per treatment, we used Origin Pro software to perform a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Tukey’s test applied for multiple comparisons of means; p < 0.05 was set as the level of statistical significance82.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings reported in this study are available in the paper.

References

World Food Programme. Hunger, Conflict, and Improving the Prospects for Peace. Rome, Italy. https://www.wfp.org/publications/hunger-conflict-and-improving-prospects-peace-fact-sheet-2020 (October 2020).

United-Nations. World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision.(United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2017).

Alexandratos, N. & Bruinsma, J. World Agriculture Towards 2030/2050: The 2012 Revision ESA Working Paper No. 12-03. Rome, FAO (FAO, 2012).

FAO. The Future of Food and Agriculture: Trends and Challenges (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2017).

FAO. Global Agriculture Towards 2050 1–4 (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2009).

Ulrike, G., Anja F., Thanh, N. T., & Olaf, E. Food security and the dynamics of wheat and maize value Chains in Africa and Asia.Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 4, (317) https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.617009 (2021).

FAO. Global Food Losses and Food Waste—Extent, Causes, and Prevention. Rome. http://www.fao.org/3/i2697e/i2697e.pdf (2011).

Mesterhazy, A., Olah, J. & Popp, J. Losses in the grain supply chain: Causes and solutions. Sustainability https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062342 (2020).

Jayas, D. S. Storing grains for food security and sustainability. Agric. Res. 1, 21–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40003-011-0004-4 (2012).

Lal, R. Feeding 11 billion on 0.5 billion hectare of area under cereal crops. Food Energy Secur. 5, 239–251. https://doi.org/10.1002/fes3.99 (2016).

Rodell, M., Velicogna, I. & Famiglietti, J. S. Satellite-based estimates of groundwater depletion in India. Nature 460, 999-U980. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08238 (2009).

Solander, K. C., Reager, J. T., Wada, Y., Famiglietti, J. S. & Middleton, R. S. GRACE satellite observations reveal the severity of recent water over-consumption in the United States. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07450-y (2017).

Scanlon, B. R., Longuevergne, L. & Long, D. Ground referencing GRACE satellite estimates of groundwater storage changes in the California Central Valley, USA. Water Resour. Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011wr011312 (2012).

Famiglietti, J. S. The global groundwater crisis. Nat. Clim. Chang. 4, 945–948 (2014).

FAO. Seeds Toolkit-Module 6: Seed Storage. Rome, pp. 112. http://www.fao.org/3/ca1495en/CA1495EN.pdf (2018).

Sawicka, B. Post-harvest losses of agricultural produce. In: Leal Filho, W., Azul, A., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P., Wall, T. (eds) Zero Hunger. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69626-3_40-1 (2019).

De Lucia, M. A. D. Agricultural Engineering in Development: Post-harvest Operations and Management of Foodgrains (FAO Agricultural Services, 1994).

Hodges, R. J., Buzby, J. C. & Bennett, B. Postharvest losses and waste in developed and less developed countries: Opportunities to improve resource use. J. Agric. Sci. 149, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021859610000936 (2011).

Kumar, D. & Kalita, P. Reducing postharvest losses during storage of grain crops to strengthen food security in developing countries. Foods 6, 8–8. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods6010008 (2017).

Abedin, M. R. M., Mia, M. & Rahman, K. In-store losses of rice and ways of reducing such losses at farmers’ level: An assessment in selected regions of Bangladesh. J. Bangladesh Agric. Univ. 10, 133–144. https://doi.org/10.3329/jbau.v10i1.12105 (2012).

Tesfaye, W. & Tirivayi, N. The impacts of postharvest storage innovations on food security and welfare in Ethiopia. Food Policy 75, 52–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.01.004 (2018).

Boxall, R. A. Post harvest-losses to insects–A world overview. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 48, 137–152 (2001).

Rachoń, L.B.-M.A. & Szumiło, G. Mycotoxin contamination of grain of selected winter wheat genotypes. Pol. J. Agron. 25, 13–18 (2016).

Kumar, R., Mishra, A. K., Dubey, N. K. & Tripathi, Y. B. Evaluation of Chenopodium ambrosioides oil as a potential source of antifungal, antiaflatoxigenic and antioxidant activity. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 115, 159–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.10.017 (2007).

Liu, Y. & Wu, F. Global burden of aflatoxin-induced hepatocellular carcinoma: A risk assessment. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 818–824. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.0901388 (2010).

Roberts, E. H. & Ellis, R. H. Water and seed survival. Ann. Bot. 63, 39–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a087727 (1989).

Bradford, K. J., Dahal, P. & Bello, P. Using relative humidity indicator paper to measure seed and commodity moisture contents. Agric. Environ. Lett. https://doi.org/10.2134/ael2016.04.0018 (2016).

Bradford, K. J. et al. The dry chain: Reducing postharvest losses and improving food safety in humid climates. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 71, 84–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2017.11.002 (2018).

Bewley, J. D., Bradford, K. J., Hilhorst, H. W. M. & Nonogaki, H. Seeds: Physiology of Development, Germination and Dormancy 3rd edn. (Springer, 2013).

Harrington, J. F. In Seed Biology, Vol. III (ed. Kozlowski, T. T.) (Academic Press, 1972).

Harrington, J. F. Biochemical basis of seed longevity. Seed Sci. Technol. 1, 453–461 (1973).

Delouche, J. C., Matthes, R. K., Dougherty, G. M. & Boyd, A. H. Storage of seed in sub-tropical and tropical regions. Seed Sci. Technol. 1, 671–700 (1973).

Roberts, E. H. Predicting the storage life of seeds. Seed Sci. Technol. 1, 499–514 (1973).

Roberts, E. H. Viability of Seeds (Springer, 2012).

Harrington, J. F. Drying, storage, and packaging seed to maintain germination and vigor. Seed Technology Papers. 44. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/seedtechpapers/44 (1959).

Bakhtavar, M. A. & Afzal, I. Climate smart dry chain technology for safe storage of quinoa seeds. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69190-w (2020).

Murdock, L. L. & Baoua, I. B. On Purdue Improved Cowpea Storage (PICS) technology: Background, mode of action, future prospects. J. Stored Prod. Res. 58, 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jspr.2014.02.006 (2014).

Baoua, I. B., Amadou, L. & Murdock, L. L. Triple bagging for cowpea storage in rural Niger: Questions farmers ask. J. Stored Prod. Res. 52, 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jspr.2012.12.004 (2013).

Murdock, L. L., Margam, V., Baoua, I., Balfe, S. & Shade, R. E. Death by desiccation: Effects of hermetic storage on cowpea bruchids. J. Stored Prod. Res. 49, 166–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jspr.2012.01.002 (2012).

Bakhtavar, M. A., Afzal, I. & Basra, S. M. A. Moisture adsorption isotherms and quality of seeds stored in conventional packaging materials and hermetic Super Bag. PLoS One https://doi.org/10.1371/jounal.pone.0207569 (2019).

Gupta, M. K., Srivastava, R. K. & Bisaria, H. Potential of jute fibre reinforced polymer composites: a review. Int. J. Fiber Textile Res. 5, 30–38 (2015).

Wang, W.-M., Cai, Z.-S. & Yu, J.-Y. Study on the chemical modification process of jute fiber. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 3, 155892500800300200. https://doi.org/10.1177/155892500800300203 (2008).

Rajesh, G. & Prasad, A. V. R. Tensile properties of successive alkali-treated short jute fiber reinforced PLA composites. Procedia Mater. Sci. 5, 2188–2196 (2014).

Mwaikambo, L. Y. & Ansell, M. P. Chemical modification of hemp, sisal, jute, and kapok fibers by alkalization. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 84, 2222–2234. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.10460 (2002).

Ali, A. et al. Hydrophobic treatment of natural fibers and their composites—a review. J. Ind. Text. 47, 2153–2183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1528083716654468 (2018).

Manandhar, A., Milindi, P. & Shah, A. An overview of the post-harvest grain storage practices of smallholder farmers in developing countries. Agriculture 8, 57 (2018).

Nagpal, M. & Kumar, A. Grain losses in India and government policies. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 4, 143–143 (2012).

Barthlott, W. & Neinhuis, C. Purity of the sacred lotus, or escape from contamination in biological surfaces. Planta 202, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004250050096 (1997).

Mahadik, G. A. et al. Superhydrophobicity and size reduction enabled Halobates (Insecta: Heteroptera, Gerridae) to colonize the open ocean. Sci. Rep. 10, 7785. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64563-7 (2020).

Das, R., Ahmad, Z., Nauruzbayeva, J. & Mishra, H. Biomimetic coating-free superomniphobicity. Sci. Rep. 10, 7934. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64345-1 (2020).

Pan, Z. et al. The upside-down water collection system of Syntrichia caninervis. Nat. Plants 2, 16076. https://doi.org/10.1038/nplants.2016.76 (2016).

Parker, A. R. & Lawrence, C. R. Water capture by a desert beetle. Nature 414, 33–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/35102108 (2001).

Darmanin, T. & Guittard, F. Superhydrophobic and superoleophobic properties in nature. Mater. Today 18, 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mattod.2015.01.001 (2015).

Narhe, R. D. & Beysens, D. A. Water condensation on a super-hydrophobic spike surface. Europhys. Lett. 75, 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1209/epl/i2006-10069-9 (2006).

Ray, D., Sarkar, B. K., Rana, A. K. & Bose, N. R. Effect of alkali treated jute fibres on composite properties. Bull. Mater. Sci. 24, 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02710089 (2001).

Chauhan, P., Kumar, A. & Bhushan, B. Self-cleaning, stain-resistant and anti-bacterial superhydrophobic cotton fabric prepared by simple immersion technique. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 535, 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2018.09.087 (2019).

Bhushan, B. Biomimetics: Lessons from nature—an overview. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 367, 1445–1486. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2009.0011 (2009).

Gassan, J. & Bledzki, A. K. Possibilities for improving the mechanical properties of jute/epoxy composites by alkali treatment of fibres. Compos. Sci. Technol. 59, 1303–1309. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0266-3538(98)00169-9 (1999).

Taha, I., Steuernagel, L. & Ziegmann, G. Optimization of the alkali treatment process of date palm fibres for polymeric composites. Compos. Interfaces 14, 669–684. https://doi.org/10.1163/156855407782106528 (2007).

Kuruvilla, J., Sabu, T., Pavithran, C. & Brahmakumar, M. Tensile properties of short sisal fiber-reinforced polyethylene composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 47, 1731–1739. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.1993.070471003 (1993).

Chen, H. et al. Effect of alkali treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of individual bamboo fibers. Cellulose 24, 333–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-016-1116-6 (2017).

Wang, X., Chang, L. L., Shi, X. L. & Wang, L. H. Effect of hot-alkali treatment on the structure composition of jute fabrics and mechanical properties of laminated composites. Materials https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12091386 (2019).

Oushabi, A. et al. The effect of alkali treatment on mechanical, morphological and thermal properties of date palm fibers (DPFs): Study of the interface of DPF–polyurethane composite. South Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 23, 116–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajce.2017.04.005 (2017).

Subramanian, N. et al. Evaluating the potential of superhydrophobic nanoporous alumina membranes for direct contact membrane distillation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 533, 723–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2018.08.054 (2019).

Gallo Jr, A., K. et al. Superhydrophobic sand mulches increase agricultural productivity in arid regions. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2102.00495 (2021).

Mishra, H. et al. Time-dependent wetting behavior of PDMS surfaces with bioinspired, hierarchical structures. ACS Appl. Mater Interfaces 8, 8168–8174. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.5b10721 (2016).

Kaufman, Y. et al. Simple-to-Apply wetting model to predict thermodynamically stable and metastable contact angles on textured/rough/patterned surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 5642–5656. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b00003 (2017).

Shi, M., Das, R., Arunachalam, S., & Mishra, H. Unexpected Suppression of Leidenfrost Phenomenon on Superhydrophobic Surfaces. arXiv preprint. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2102.02499.pdf (2021).

Gallo Jr., A., Tavares, F., Das, R. & Mishra, H., How Particle–Particle and Liquid–Particle Interactions Govern the Fate of Evaporating Liquid Marbles. Soft Matter, https://doi.org/10.1039/D1SM00750E (2021)

Ghosh, S. K., Ray Gupta, K., Bhattacharyya, R., Sahu, R. B. & Mandol, S. Improvement of life expectancy of jute based needlepunched geotextiles through bitumen treatment. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. E 95, 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40034-014-0036-y (2014).

Das, R. et al. Proof-of-concept for gas-entrapping membranes derived from water-loving SiO2/Si/SiO2 wafers for green desalination. JoVE https://doi.org/10.3791/60583 (2020).

Pillai, S. et al. A molecular to macro level assessment of direct contact membrane distillation for separating organics from water. J. Membr. Sci. 608, 118140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2020.118140 (2020).

Arunachalam, S. et al. Rendering SiO2/Si surfaces omniphobic by carving gas-entrapping microtextures comprising reentrant and doubly reentrant cavities or pillars. JoVE https://doi.org/10.3791/60403 (2020).

Das, R., Arunachalam, S., Ahmad, Z., Manalastas, E. & Mishra, H. Bio-inspired gas-entrapping membranes (GEMs) derived from common water-wet materials for green desalination. J. Membr. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2019.117185 (2019).

Gonzalez-Avila, S. R. et al. Mitigating cavitation erosion using biomimetic gas-entrapping microtextured surfaces (GEMS). Sci. Adv. 6, eaax6192. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aax6192 (2020).

Arunachalam, S., Das, R., Nauruzbayeva, J., Domingues, E. M. & Mishra, H. Assessing omniphobicity by immersion. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 534, 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2018.08.059 (2019).

Domingues, E. M., Arunachalam, S. & Mishra, H. Doubly reentrant cavities prevent catastrophic wetting transitions on intrinsically wetting surfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interface 9, 21532–21538. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b03526 (2017).

Vermeulen, S. J., Campbell, B. M. & Ingram, J. S. I. Climate change and food systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 37, 195–222. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-020411-130608 (2012).

Jury, W. A. & Vaux, H. The role of science in solving the world’s emerging water problems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15715–15720. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0506467102 (2005).

Wexler, A. & Hasegawa, S. Relative humidity–temperature relationships of some saturated salt solutions in the temperature range 0-degree to 50-degrees-C. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. 53, 19–26. https://doi.org/10.6028/jres.053.003 (1954).

Suma, A., Sreenivasan, K., Singh, A. K. & Radhamani, J. Role of relative humidity in processing and storage of seeds and assessment of variability in storage behaviour in Brassica spp. and Eruca sativa. Sci. World J. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/504141 (2013).

OriginPro. OriginLab Corporation. https://www.originlab.com/. Northampton, MA, USA (Version 2017).

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this publication was supported by funding from King Abdullah University of Science and Technology under award number BAS/1/1070-01-01. The co-authors thank Mr. Sankara Arunachalam (KAUST) for his assistance with the scanning electron microscopy of jute bags; Mr. Xavier Pita, Senior Scientific illustrator, KAUST, for creating Figs. 1 and 7; Dr. Nishan MA for sourcing and preparing the jute bags; Mrs. Juliet Aber for sewing the jute bags used in the seed storage experiment; Prof. Magdi Mousa of the King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, for providing the wheat grains used in this study; and Mr. Firas Atef Baba (KAUST) for providing the jute bags.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.O. designed and performed the surface treatments, characterized the materials, and conducted the seed storage and germination work; K.O. also analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. A.G.J. assisted with the experimental design, data analysis, analysis of wetting behaviors, and manuscript revision. H.M. conceived the idea, supervised the research, and co-composed the manuscript with K.O.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Based on this work, two of the co-authors, KO and HM, have filed a provisional patent application (USPTO Serial No. 63/141,104), while AGJ has no related conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Odokonyero, K., Gallo, A. & Mishra, H. Nature-inspired wax-coated jute bags for reducing post-harvest storage losses. Sci Rep 11, 15354 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93247-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93247-z

This article is cited by

-

Insect-inspired breathing interfaces: investigating robustness of coating-free gas entrapping microtextured surfaces under pressure cycles

Communications Engineering (2024)

-

Constraints on industrial-scale application of lignocellulosic fiber and biomass in food packaging

Iranian Polymer Journal (2024)

-

A logarithmically amortising temperature effect for supervised learning of wheat solar disinfestation of rice weevil Sitophilus oryzae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) using plastic bags

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Assessing the non-wettability and sustainability of cellulosic jute for roadway applications

Cellulose (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.