Abstract

The onset and worsening of some diseases are related to the variation and instability of gut microbiota. However, studies examining the personal variation of gut microbiota in detail are limited. Here, we evaluated the yearly variation of individual gut microbiota in 218 Japanese subjects aged 66–91 years, using Jensen-Shannon distance (JSD) metrics. Approximately 9% of the subjects showed a substantial change, as their formerly predominant bacterial families were replaced over the year. These subjects consumed fermented milk products less frequently than their peers. The relationship between the intake frequencies of fermented milk products containing Lacticaseibacillus paracasei strain Shirota (LcS) and JSD values was also investigated. The intra-individual JSD of subjects ingesting LcS products ≥ 3 days/week over the past 10 years was statistically lower than the < 3 days/week group (P = 0.045). Focusing on subjects with substantial gut microbiota changes, only 1.7% of the subjects were included in the LcS intake ≥ 3 days/week group whereas 11.3% were found in the < 3 days/week group (P = 0.029). These results suggest that about one-tenth of the elderly Japanese could experience a substantial change in their gut microbiota during a 1-year period, and that the habitual intake of probiotics may stabilize their gut microbiota.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The human gut microbiota is a highly complex ecosystem, composed of a large number of bacteria (1010–1011cells/g feces) drawn from several hundreds of bacterial species1. The composition of the human gut microbiota is associated with certain types of disorders and the development of diseases, such as obesity2, diabetes3,4 and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)5,6. In addition, some clinical trials have shown that a transplantation of fecal microbiota is highly effective in protecting against a recurrence of Clostridioides difficile infection7,8. Thus, the maintenance of favorable gut microbiota plays an important role in maintaining human health and in the prevention and treatment of many diseases.

The gut microbiota in human adults is generally recognized to remain stable in population-based studies. For example, most predominant bacterial species flourish in the human gut over periods of years9,10, and intra-individual (within-person) microbial variations are smaller than inter-individual (between-person) differences10,11,12,13. On the other hand, some studies have suggested that disturbance and instability in the gut microbiota are associated with risks to host health, such as exacerbation of human IBD14, neuro-inflammation and amyloidosis in a murine Alzheimer’s disease model15,16. Therefore, instability of gut microbiota may be considered as a potential risk to human health. However, studies examining details of the variation of gut microbiota within individuals are limited. Indeed, little is known about the incidence, causes and remedies for human microbial instability and the association between personal lifestyle and the temporal stability of gut microbiota.

Probiotics are defined by the World Health Organization (WHO)/Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) as ‘Live microorganisms which confer a health benefit on the host when administered in adequate amounts’17. Typical examples are lactobacilli and bifidobacteria. Certain types/species of bacteria are also important to gastrointestinal health, and the processes involved appear to be facilitated by the regular ingestion of fermented milk products containing lactic acid bacteria. The ingestion of a specific probiotic bacterium, the Lacticaseibacillus paracasei strain Shirota (LcS), previously known as Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota18, is very popular both in Japan and world-wide; respective rates of consumption averaged about 8.9 and 41 million bottles per day in the year 201919. LcS reaches the intestine alive20,21,22,23 and helps to ensure a good balance of gut microbiota23,24,25,26. Moreover, many other beneficial effects have been claimed for the regular ingestion of LcS, including improvement of bowel movements23,25, immunoregulation27,28 and protection against infection24,29,30,31. However, the impact of the regular consumption of the probiotics, including LcS products, on the stability of human gut microbiota remains unknown.

Over a 20-year period since 2000, we have been conducting an epidemiological study in the community of Nakanojo Town, Gunma Prefecture, Japan (the Nakanojo Study), assessing relationships between patterns of habitual physical activity and health in people aged 65 years and older32,33,34,35. Since 2014, we have also been collecting information on the subject’s frequency of the intake of fermented milk products, including LcS, and have previously reported the reduced risks of developing hypertension36 and infrequent bowel movements37 among elderly individuals who habitually take fermented milk products containing LcS.

Moreover, we started to analyze the subject’s fecal microbiota composition from 2015. These long-term collected data on the gut microbiota composition and the frequency of fermented product intake may provide an opportunity to explore the temporal variations of the gut microbiota in individual subjects and to identify any relationship between the consumption of probiotics and changes in microbiota composition.

The aim of this study was to assess the temporal variability of gut microbiota among elderly Japanese people over a 1-year period and to explore any possible associations between the intake frequency of fermented milk products containing LcS and the stability of the gut microbiota.

Results

We selected 218 elderly Japanese people from the participants of the Nakanojo Study32,33,34,35, who provided fecal samples annually for 2 consecutive years or longer. The intra-individual yearly variations and the inter-individual differences in the composition of microbiota were assessed using Jensen-Shannon distance38 (JSD) and Bray–Curtis dissimilarity39 (BCD) metrics. Higher values of JSD and BCD indicate more different compositions of gut microbiota.

The variations of gut microbiota within and between subjects

Firstly, we compared the intra-individual temporal variations and inter-individual differences in the gut microbiota, and defined the subjects who experienced large temporal variations in their gut microbiota. The intra-individual JSD values (Supplementary Fig. S1A) of the gut microbial composition [median (minimum–maximum) of 0.205 (0.056–0.606)] were significantly smaller than the inter-individual differences [0.401 (0.117–0.763) over the first year and 0.395 (0.104–0.763) over the second year] (Fig. 1A). In terms of BCD metrics, similar results were observed (Supplementary Fig. S2). In this study, subjects whose intra-individual variability exceeded inter-individual differences in microbiota were defined as “subjects who experienced a substantial change in gut microbiota”. Thus, the threshold of intra-individual JSD was set at 0.4, which was equivalent to the median of inter-individual JSDs (0.4) and approximately twice the median of intra-individual JSDs (0.2).

Intra-individual variations and inter-individual differences in gut microbial composition, quantified by Jensen-Shannon distance (JSD). (A) Comparison of JSD values between intra-individuals and inter-individuals by Steel’s tests. ***P < 0.001. (B) Distribution of intra-individual variations among the 218 subjects. The orange line indicates the median of the inter-individual JSDs (approximately 0.4).

The compositional changes of gut microbiota in subjects with JSD ≥ 0.4

Nineteen of 218 subjects (8.7%) had intra-individual JSD values higher than 0.4 (Fig. 1B), implying that they experienced a substantial change in the gut microbiota over a 1-year period. The detailed changes in the composition of the gut microbiota in annual fecal sample sets are presented in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S3. The 19 subjects with a JSD ≥ 0.4 showed that the noted compositional changes of microbiota were accompanied by the replacement of predominant bacteria at the family level over the 1-year period. In contrast, the remaining subjects with a JSD < 0.4 maintained the composition of the predominant bacterial community with moderate or little changes in their respective abundance.

Changes of the predominant gut microbial composition at the family level between the first and second year. The subjects were classified into three groups by intra-individual Jensen-Shannon distance (JSD) range [(A) JSD ≥ 0.4 (large), (B) 0.15 ≤ JSD < 0.4 (moderate) or (C) JSD < 0.15 (small variations in their gut microbiota between the 2 years)]. The 6 respective representatives are shown.

Table 1 shows the background data for the 19 subjects with a JSD ≥ 0.4 and the other 199 subjects with lower JSD values. The percentages of current smokers and of those taking antibiotic medicines were significantly higher for the former than for the latter (15.8% vs 3.5% and 10.5% vs 0.5%, respectively). Also, the diastolic blood pressure was significantly lower in the former than in the latter (69.5 ± 13.3 mmHg vs 74.5 ± 9.6 mmHg), although there was no difference in the prevalence of hypertension between the groups (Supplementary Table S1). In addition, the intake frequencies of fermented milk products containing LcS were lower for the former than for the latter; the frequency for the past 10-years was about one-third for the former versus the latter. Supplementary Figure S4 presents the principal coordinate analysis plots of gut microbiota for subjects with JSDs < 0.4 and ≥ 0.4. Permutational multivariat analyses of variance revealed that there were no significant differences in the gut microbiota between the subjects of the two JSD groups at the first and second year.

Supplementary Table S2 summarizes the changes in medical history, medication status and lifestyle in subjects with a JSD ≥ 0.4 between the two fecal collections. Two subjects developed a new disease (ID 5002: ischemic enteritis, ID 6461: choledocholithiasis) during the year. Other 3 subjects took antibiotics or gastric acid lowering medication during the week preceding the second collection (ID 6202, 5084 and 5300). Eleven subjects with a JSD ≥ 0.4 had no changes in their medical history, medication status or lifestyle (ID 5262, 7062, 6086, 5398, 5378, 7137, 6442, 6636, 5400, 5158 and 5144). No consistent changes in physical activity patterns, smoking habits or alcohol consumption were observed between the two time points among the 19 subjects with a JSD ≥ 0.4.

The persistence of temporal variations in individual gut microbiota

To investigate the persistence of the temporal variability in gut microbiota, 135 subjects who provided their fecal samples for three consecutive years were selected from the 218 subjects validated in this study (Supplementary Fig. S1B). The correlation between the intra-individual JSDs of the first–second (JSD1st–2nd) and second–third fecal samples (JSD2nd–3rd) were analyzed. We noted that JSD1st–2nd was strongly and significantly correlated with JSD2nd–3rd (Fig. 3; r = 0.57, P < 0.001). For subjects who showed a substantial variation over the next year (JSD2nd–3rd ≥ 0.4), 57.1% (8/14) were found in the subjects with a JSD1st–2nd ≥ 0.4 compared to only 6.6% (8/121) with a JSD1st–2nd < 0.4; a Fisher’s exact test showed the significant difference in the prevalence of JSD2nd–3rd ≥ 0.4 between these two groups (P < 0.001). In 83.7% of the subjects (113/135), both JSD1st–2nd and JSD2nd–3rd showed < 0.4, implying that there had been no substantial change in their gut microbiota over the 2 years. On the other hand, 10.4% (14/135) of the subjects experienced a substantial change in their gut microbiota once within the 2 year, with values of 0.4 or higher in either JSD1st–2nd or JSD2nd–3rd. Furthermore, 5.9% (8/135) showed continuous gut microbiota changes over the 2 years, with values of 0.4 or higher in both JSD1st–2nd and JSD2nd–3rd. Supplementary Figure S5 shows the changes in the composition of gut microbiota for these 8 subjects in 3 fecal collections. In 3 of the 8 subjects, JSD1st–3rd was also 0.4 or higher, suggesting that the composition of microbiota was remarkably different in each fecal collection. In the remaining 5 subjects, JSD1st–3rd was lower than 0.4; thus, the composition of their gut microbiota returned to the initial state in the 3rd sample collection (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Association between intra-individual Jensen-Shannon distance from the first to the second (JSD1st–2nd) and from the second to the third (JSD2nd–3rd) fecal collections with respect to yearly changes in the gut microbiota. Spearman’s rank correlation analysis assessed the association between the JSDs during two periods.

Relationships between the intake frequency of fermented milk products and temporal variations of gut microbiota

We investigated the relationship between the intake frequencies of fermented milk products (Supplemental Table S3) and the temporal variation of gut microbiota over a 1-year period in the 218 subjects mentioned above (Fig. 1B). Among subjects ingesting LcS products ≥ 3 days/week over a 10-year period, the intra-individual JSD of gut microbial composition was statistically lower than that of the < 3 days/week group [median (minimum–maximum) of 0.185 (0.057–0.494) and 0.211 (0.056–0.606), respectively, P = 0.045] (Fig. 4). In addition, the percentages of the subjects whose intra-JSDs showed ≥ 0.4 were 11.3% (18/160) in the < 3 days/week group but only 1.7% (1/58) in the ≥ 3 days/week group; a Fisher’s exact test showed that this 9% difference between the two groups was statistically significant (P = 0.029). With respect to intake over a 1-month and a 5-year period, the intra-individual JSD and the incidence of major variation of gut microbiota in the ≥ 3 days/week group tended to be similarly lower than those for the < 3 days/week group, although insignificantly so (Fig. 4). In terms of overall fermented milk products, the corresponding differences in the intra-individual JSD were not statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. S6). Similar results were observed by the BCD metrics (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Intra-individual Jensen-Shannon distance (JSD) in subjects consuming fermented milk products containing Lacticaseibacillus paracasei strain Shirota (LcS) < 3 or ≥ 3 days/week during the past 1-month, 5-year and 10-year periods. Independent differences in the JSD between groups were assessed by analyses of covariance, after adjusting data for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, and alcohol intake.

Table 2 shows the background data of subjects ingesting LcS products < 3 and ≥ 3 days/week over a 10-year period. Moderate alcohol consumers showed 45.6% (73/160) in the < 3 days/week group and 22.4% (13/58) in the ≥ 3 days/week group, with this inter-group difference being statistically significant (P < 0.05). On the other hand, no significant differences were detected in the taking of antibiotics or gastric acid lowering medicines between < 3 and ≥ 3 days/week groups. Furthermore, even after adjusting for the intake of antibiotics or gastric acid lowering medicines, the values of intra-individual JSD remained lower in subjects ingesting LcS products ≥ 3 rather than < 3 days/week (P = 0.055 or 0.048, respectively; data not shown). There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups with respect to any of the other variables examined, except the intake of vitamin C. In terms of the other intake periods and intake of overall fermented milk products, similar results were observed (data not shown).

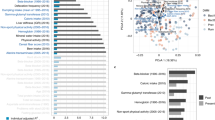

Figure 5 shows net changes in the abundance of each bacterial family during a year. In all bacterial families, the individual changes of relative abundance across the two time points were distributed in both positive (increasing) and negative (decreasing) directions, with their medians showing approximately 0% in both groups of LcS intake < 3 and ≥ 3 days/week. On the other hand, comparing dispersions of variations in each bacterial abundance between the two groups by Levene’s tests showed that Ruminococcaceae and Lactobacillaceae in the ≥ 3 days/week group were significantly lower than those in the < 3 days/week group (Fig. 5, P = 0.008 and 0.026, respectively).

Changes in the relative abundance of each predominant bacteria during a year in subjects consuming fermented milk products containing Lacticaseibacillus paracasei strain Shirota (LcS) < 3 or ≥ 3 days/week over the past 10-year period. Independent differences between groups in terms of dispersions of changes in the abundance were assessed by Levene’s tests. P values with < 0.05 are shown.

Discussion

This epidemiological study showed that the gut microbiota of the general Japanese elderly people is comprehensively stable (Fig. 1), supporting other population-based observations9,10,11,12,13. However, approximately 9% (19/218) of the subjects showed considerable changes in the composition of the gut microbiota over a year, with a replacement of the predominant bacterial families. Moreover, a strong positive correlation was observed between JSD1st–2nd and JSD2nd–3rd (Fig. 3), among the subjects who provided feces for 3 consecutive years. These results suggest that the stability of the gut microbiota composition in the elderly persists, and those who experience major changes in their gut microbiota are likely to have such changes subsequently. No common direction or trend in the changes of gut microbiota composition was observed (Figs. 2, and 5).

Among the 19 subjects who experienced a substantial change in the gut microbiota (JSD ≥ 0.4 group), 2 subjects developed new pathologies (ischemic enteritis and choledocholithiasis) over the year, and 3 other subjects took antibiotics or gastric secretion inhibitors just before the second fecal collection (Supplementary Table S2). Moreover, the 3-year investigation showed that continuous and significant changes in the gut microbiota were observed annually in 3 subjects (ID 5002, 5084, 5144; Supplementary Fig. S5). ID 5002 was the only subject who developed ischemic enteritis between the first and second year, and ID 5084 was found to be taking antibiotics. On the other hand, there were subjects whose gut microbiota changed significantly, but then returned to the state before the change (ID 6202, 6636, 5262, 5398, 6086; Supplementary Fig. S5). Among these subjects, one subject (ID 6202) was taking antibiotics at the second fecal collection, and unlike ID 5084 above, the changes in microbiota were transient. We attempted to determine the cause of the changes in the gut microbiota based on the personal characteristics collected through this study, but did not lead to clarification of the responsible factors. These results suggest that there might be “individual characteristics” that cannot be explained by the use of antibiotics, and changes in disease onset, physical condition and/or lifestyle habits. Relationships between the onset of disease and/or long-term effects of antibiotic use and the ongoing changes in the gut microbiota remain unknown. Because the number of subjects whose gut microbial composition changed was small in this study, larger-sample studies are needed to clarify the factors that influence continuous or transient changes in gut microbiota.

We have also done a comparison on the baseline characteristics between subjects who changed in their gut microbiota (JSD ≥ 0.4 group) and those who did not (JSD < 0.4 group). The percentages of antibiotics users and current smokers were significantly greater in the JSD ≥ 0.4 group compared to their peers (Table 1). However, antibiotic takers and current smokers were only 2 and 3 of the 19 subjects, respectively, suggesting limited effects on the substantial changes of gut microbiota.

Diastolic blood pressure was significantly lower in the JSD ≥ 0.4 group than that in the JSD < 0.4 group (Table 1), suggesting that blood pressure may be affected by microbiota changes, although both mean values were within an optimal range of diastolic pressure. On the other hand, the cause-and-effect relationship was unidentified in this study. Since previous studies have reported that gut microbiota may affect blood pressure40,41, it is possible that changes in the microbiota may affect the blood pressure. Future studies will be necessary to clarify the causal relationship and its clinical importance through prospective and interventional studies.

Many other factors such as the intake of dietary fiber and the frequency of defecation also have an influence on gut microbiota42,43. Although the nutrient intake and stool frequency were similar for two groups of subjects with different JSDs, the intake frequencies of products containing lactic acid bacteria in subjects with a JSD ≥ 0.4 were less than those of their peers (Table 1).

Lactic acid bacteria have been used in the production of fermented food and patronized in all over the world since ancient times, and LcS is recognized as a representative probiotic strain. The present investigation confirmed statistically significant differences in the intra-individual variation of gut microbiota over a year between subjects taking LcS fermented milk products < 3 and ≥ 3 days/week for the past 10 years. The incidence of “substantial variation of gut microbiota” in the latter subjects was less than one-fifth of that in the former subjects. Likewise, lower dispersions of variations in the bacterial abundance of Ruminococcaceae and Lactobacillaceae over a year were seen in subjects ingesting LcS products ≥ 3 rather than < 3 days/week. Therefore, it appears that habitual intake of fermented milk products containing LcS is associated with a more stable gut microbiota composition, mainly by suppressing the variations of these bacterial families.

LcS has been shown to have a high tolerance to gastric and bile acids44 and to reach the intestine alive20,21,22,23, suggesting that the production of organic acids such as lactic acid is increased45, lowering pH in the intestine. LcS is also known to provide a good balance of gut microbiota both by increasing the abundance of beneficial bacteria such as bifidobacteria and lactobacilli and by decreasing the abundance of harmful bacteria23,24,25,26. Together, these improvements in gut microbiota and environments by LcS may contribute directly to the stability of the composition of gut microbiota, leading to the stabilization of gut microbiota among subjects taking LcS-containing fermented milk products ≥ 3 days/week.

Furthermore, LcS is known to have a preventive effect of infection24,29,30,31, which may reduce the frequency of drug use and consequently stabilize gut microbiota. However, no differences were detected in the taking of antibiotics or gastric acid lowering medicines between < 3 and ≥ 3 days/week groups, and the values of intra-individual JSD remained lower in the ≥ 3 days/week group after adjusting for the intake of antibiotics or gastric acid lowering medicines. Thus, the intake of antibiotics or gastric acid lowering medicines does not appear to have great effect on the relationship between the intake frequency of lactic acid bacteria and the stability of microbiota.

Other factors such as stress suppression may be involved in the stabilization of gut microbiota by LcS, as LcS has been reported to suppress naturalistic stresses46,47,48. Moreover, LcS has also been reported to have immunoregulatory effects, including the enhancement of natural killer cell activity49,50,51 and the maintenance of salivary Immunoglobulin A (IgA) level28. Recent reports have suggested that gut microbiota are regulated by host IgA52,53,54, so that the effect of LcS on humoral immunity of the host may have contributed to the stabilization of gut microbiota. Further studies are needed to clarify the mechanism of higher stability among subjects who habitually take fermented milk products containing LcS.

There are some limitations to the current investigation. The design was partly retrospective and observational rather than prospective and experimental, so that causation cannot be inferred. The estimated frequency of LcS intake was based on questionnaires completed regularly and repeatedly by the subjects, using a standardized methodology36,37. Furthermore, the relative abundances of the gut microbiota were determined using the standardized methodology of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene amplicon analysis37,47. These facts strengthen the practical significance of the observed relationship between the frequency of LcS-containing product consumption and intra-individual variations in gut microbiota. On the other hand, individuals ingesting fermented milk supplements ≥ 3 days/week might differ from their peers in terms of a greater overall interest in a healthy lifestyle, including other facets of behavior that could limit instability in their gut microbiota. Among the lifestyle covariates we examined, and with the exception of less alcohol consumption and more vitamin C consumption in those ingesting fermented milk ≥ 3 days/week, the two groups appeared to be well matched. Moreover, we covaried the major important lifestyle determinants of gut microbiota (age, sex, body mass index, cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption), although the statistical adjustment for these factors may have been incomplete. Although most people drink up the entire bottle of LcS, the amount and frequency of fermented milk intake are not necessarily closely related. Also, the variations of gut microbiota are linked to many other aspects of food intake, such as the content of dietary fiber and cereals, and the response to a frequent intake of LcS-containing fermented milk might diverge in a population whose diet differed substantially from the rice-based nutrition of the elderly in rural Japan. In addition, we could not consider the impact of uncollected data such as stress, long-term status of medication and changes in family structure on the intra-individual stability of gut microbiota. Therefore, it is necessary to replicate this study in populations of various ages and consuming various diets. Moreover, relationships between the instability of gut microbiota and potential risks to human health are still unresolved, and prospective studies are required to examine the clinical significance of the stability of gut microbiota and the effectiveness of continuous intake of LcS fermented milk products.

In conclusion, our study suggests that about one-tenth of elderly Japanese could experience a substantial compositional change in the predominant gut microbiota during a year. Also, those who experienced major changes in their gut microbiota were more likely to have subsequent microbiota changes. These results suggest that the individual stability of gut microbiota is continuously maintained and is regulated by lifestyle habits. Moreover, this study has shown for the first time that the habitual intake of probiotics, particularly LcS, may stabilize the elderly’s gut microbiota. Elucidating the mechanism of gut microbiota stabilization through the intake of probiotics and how this gut microbiota stabilization affects the health of the elderly may provide hints for the construction of a healthy society with longevity.

Methods

Subjects

The subjects were self-supporting and independent Japanese volunteers aged 65 years or older who had been recruited to the Nakanojo Study32,33,34,35. Criteria of recruitment included attendance at an annual medical examination, functional independence, and the absence of chronic or progressive conditions that could limit physical activity or have a major effect on the individual’s perceived quality of life (e.g., cancer, arthritic diseases, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and dementia). In the present study, we selected 218 subjects (99 males and 119 females) aged 66–91 years who provided fecal samples once a year for at least 2 consecutive years (Fig. S1).

Collection and treatment of fecal samples

Fecal samples were collected and treated as described previously37. In brief, subjects were given sterile feces tubes (Sarstedt AG & Co., Nümbrecht, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany) containing 2 ml of a ribonucleic acid (RNA) stabilization solution (RNAlater; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, United States) for the analyses of gut microbiota. Using the collection spoon attached to the tube cap, each subject placed a spoonful of fecal sample (approximately 500 mg) into each collection tube immediately after defecating. Samples were stored at room temperature and sent to the Yakult Central Institute within a couple of days. After arrival at the Institute, samples were weighed to calculate the fecal volume (average weight 475 ± 347 mg), suspended in nine volumes of RNAlater, and then homogenized. Two hundred μl of the fecal homogenate (equivalent to 20 mg of feces) was added to 1 ml of sterilized phosphate-buffered saline and then centrifuged at 10,000×g for 5 min. The supernatant (1 ml) was discarded, and the resulting fecal homogenate was stored at − 80 °C until deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) extraction.

Assay of gut microbiota

The relative abundances of the fecal bacterial families were determined by amplicon sequencing analysis targeting the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene, as described previously37,47, using the open-source Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) software55. Briefly, DNA was extracted from fecal samples56, and the V1–V2 region of the 16S rRNA gene of gut microbiota was amplified using the forward primer 27Fmod2-MiSeqV2 and the reverse primer 338RMiSeqV2-00144. The amplicons were purified using an Agencourt AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter K. K., Koto, Tokyo, Japan), quantified using a Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, United States), and sequenced using a MiSeq sequencing system (Illumina K. K., Minato, Tokyo, Japan).

Evaluation of gut microbiota variation

Differences in the relative abundance of the bacterial family composition between and within subjects were evaluated by calculating the JSD metrics38, which are generally used in enterotypes classification of the human gut microbiome57. The difference JSD (a, b) between samples a and b is defined as

where Pa and Pb are the abundance distributions of samples a and b and JSd (x, y) is the Jensen-Shannon divergence between two probability distributions x and y defined as

where \(m=\frac{x+y}{2}\) and KLD (x, y) is the Kullback–Leibler divergence between x and y defined as

We added a pseudocount of 0.0000001 to the abundance distributions and renormalized them to avoid zero in the numerator and/or denominator of equation. The differences in the composition of gut microbiota were also evaluated by calculating a BCD metrics39 using “vegdist” function in a “vegan” package of R software (version 3.3) (https://cran.r-project.org/)58. With these metrics, higher values indicate more widely differing compositions of gut microbiota. Substantial variation of gut microbiota within a subject was arbitrarily defined as JSD ≥ 0.4, which was higher than the median of inter-individual JSDs in this study.

Estimation of the frequency of intake of fermented milk products

The intake frequency of fermented milk products containing LcS was estimated by a modified self-administered questionnaire59,60, with pictures of a series of commercially available LcS-containing products, including “Yakult”, “Joie”, “Soful”, and “Pretio” (Yakult Honsha Co. Ltd., Minato, Tokyo, Japan), each of which contains 0.9–40 billion live LcS per bottle. Subjects were asked how many days per week they had ingested products of the type illustrated over 1-month, 5-year, and 10-year periods before the collection of fecal samples. The intake frequency of general fermented milk products, such as yogurt (including the above Yakult Honsha Co. Ltd. products), was also estimated by the same procedure. Subjects were classed as consuming a bottle of the product less than 3 days per week (designated as “ < 3 days/week”) or 3 days or more per week (designated as “ ≥ 3 days/week”), as categorized in our previous report36.

Measurement of blood pressure, physical activity patterns and physical health

Blood pressure was measured after 5 min of seated rest, using an automatic sphygmomanometer (BP-103iII; Colin Medical Technology Co. Ltd., Komaki, Aichi, Japan). At least one further measurement was made after a further 5-min rest if the initial reading suggested that an individual had become hypertensive (or rarely, hypotensive). Physical activity patterns were measured for 24 h per day over a 1-month period, using a uniaxial acceleration sensor (Lifecorder; Suzuken Co. Ltd., Nagoya, Aichi, Japan), as described previously32,33,34,35. The average number of steps taken per day and the daily cumulative duration of moderate-intensity exercise [activity demanding an energy expenditure greater than 3 metabolic equivalents (METs)] were calculated for each subject. Preferred and maximal walking speeds were determined over a 5-m distance, using a stopwatch (SVAE101; Seiko Corp., Minato, Tokyo, Japan), as described previously61. Subjects completed two trials to determine each of comfortable and maximal walking speeds; the averaged and the higher velocities were each recorded for each of the two measurements. Peak handgrip force was assessed for the dominant hand, using a Smedley dynamometer (ES-100; Evernew Co. Ltd., Koto, Tokyo, Japan). Two trials were performed, and the larger of the two readings was noted. Quantitative ultrasound measurements of osteosonic index for the calcaneus were made using an Achilles ultrasonic bone densitometer (AOS-100; Aloka Co. Ltd., Mitaka, Tokyo, Japan), as described previously62.

Assessment of anthropometric characteristics, blood profiles and medical history

The physical characteristics of subjects (age, sex, height, body mass, and body mass index) were determined by standard anthropometric techniques63. Biochemical profiles (triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, glycosylated hemoglobin A1c, blood sugar, glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase, glutamic pyruvic transaminase, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, albumin, creatinine, uric acid concentrations, and the estimated glomerular filtration rate) were also measured by standard methods (Health Sciences Research Institute Inc., Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan). The medical history was obtained from the doctor’s records.

Investigation of nutrient intake

The nutritional status of the subjects was evaluated by a certified nutritionist over a 1-week period, using Version 3.5 of the Food Frequency Questionnaire Based on Food Groups64 (FFQg; Kenpakusha Co. Ltd., Bunkyo, Tokyo, Japan), which is a 20-item questionnaire regarding the consumption of items from 29 food groups and 10 methods of food preparation. On the basis of responses to this questionnaire, the daily intake of energy, nutrients, and food groups was estimated for the 1- to 2-month period prior to the fecal sampling. The estimated nutrients included protein, lipid, carbohydrate, dietary fiber, saturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, cholesterol, sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, iron, and vitamin C.

Determination of defecation and medication status

The frequency of defecation was estimated by a self-administered questionnaire. Subjects were asked how many days they had defecated over a 1-week period before the fecal sampling. The consistency of the feces was estimated using the Bristol Stool Form Scale65 (BSFS), a diagnostic tool designed to classify the shape and type of human feces into seven distinct categories: separate hard lumps, like nuts (= 1); sausage-shaped, but lumpy (= 2); like a sausage, but with cracks on its surface (= 3); like a sausage or snake, smooth and soft (= 4); soft blobs with clear-cut edges (= 5); fluffy pieces with ragged edges, a mushy stool (= 6); and watery, no solid pieces, entirely liquid (= 7). The medication status was estimated using a self-administered questionnaire. Subjects filled out all the names of antibiotics and gastric acid lowering medicines that they had taken over a 1-week period before the fecal sampling.

Statistical analyses

Version 3.3 of the R software (https://cran.r-project.org/) was used throughout58. Steel’s tests assessed differences between the values of intra-individual JSD and inter-individual JSD. Analytical subjects were divided into two groups, based on the intra-individual JSD (< 0.4 and ≥ 0.4) or based on the intake frequency of fermented milk products (< 3 and ≥ 3 days/week) over 1-month, 5-year, and 10-year periods. Analyses of covariance assessed independent differences between groups with respect to anthropometry, physical activity, defecation, physical health, fermented milk products consumption, nutrition, and/or blood characteristics, after controlling data for age and/or sex or with respect to intra-individual JSD and BCD, after controlling for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status and alcohol consumption. Chi-square tests assessed differences between groups in male/female ratio and the percentages of current smokers, current alcohol consumers, and medicine users. Fisher’s exact tests assessed differences between groups in terms of the prevalence of diseases. Permutational multivariat analyses of variance66 with 10,000 permutations assessed differences between groups with respect to gut microbiota at the family level in the first and second year, using JSD metrics as dissimilarity indices67. Spearman’s rank correlation analyses assessed associations between JSD1st–2nd and JSD2nd–3rd. Fisher’s exact tests assessed differences between groups in terms of the incidence of substantial variation of gut microbiota (JSD ≥ 0.4). Levene’s tests assessed differences between groups in terms of the dispersions of changes in the relative abundance of gut microbiota families. All statistical contrasts were made at the 0.05 level of significance.

Ethics approval

The protocol was approved and the study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the ethics review committee of the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology with written informed consent provided by all subjects in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data availability

Gut 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject accession code PRJNA686801. The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available in this article and its Supplementary File, or from the corresponding author upon request.

Change history

04 August 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95564-9

References

Guarner, F. & Malagelada, J. R. Gut flora in health and disease. Lancet 361, 512–519 (2003).

Turnbaugh, P. J. et al. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 444, 1027–1031 (2006).

Karlsson, F. H. et al. Gut metagenome in European women with normal, impaired and diabetic glucose control. Nature 498, 99–103 (2013).

Qin, J. et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature 490, 55–60 (2012).

Chu, H. et al. Gene-microbiota interactions contribute to the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Science 352, 1116–1120 (2016).

Qin, J. et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 464, 59–65 (2010).

Van Nood, E. et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 407–415 (2013).

Kelly, C. R. et al. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on recurrence in multiply recurrent Clostridium difficile infection a randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 165, 609–616 (2016).

Fu, B. C. et al. Temporal variability and stability of the fecal microbiome: The multiethnic cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 28, 154–162 (2019).

Mehta, R. S. et al. Stability of the human faecal microbiome in a cohort of adult men. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 347–355 (2018).

Faith, J. J. et al. The long-term stability of the human gut microbiota. Science 341, 1237439 (2013).

Schloissnig, S. et al. Genomic variation landscape of the human gut microbiome. Nature 493, 45–50 (2013).

Hisada, T., Endoh, K. & Kuriki, K. Inter- and intra-individual variations in seasonal and daily stabilities of the human gut microbiota in Japanese. Arch. Microbiol. 197, 919–934 (2015).

Braun, T. et al. Individualized dynamics in the gut microbiota precede Crohn’s disease flares. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 114, 1142–1151 (2019).

Minter, M. R. et al. Antibiotic-induced perturbations in gut microbial diversity influences neuro-inflammation and amyloidosis in a murine model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 6, 30028 (2016).

Minter, M. R. et al. Antibiotic-induced perturbations in microbial diversity during post-natal development alters amyloid pathology in an aged APPSWE/PS1ΔE9 murine model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 7, 10411 (2017).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Health Organization (FAO/WHO). Health and nutrition properties of probiotics in food including powder milk with live lactic acid bacteria. http://www.fao.org/3/a-a0512e.pdf (2001).

Zheng, J. et al. A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 70, 2782–2858 (2020).

Yakult Honsha Co. Ltd. Supplemental Materials for Financial Statements. https://www.yakult.co.jp/english/ir/management/pdf/20_04_hosoku_en.pdf (2020).

Mai, T. T., Hop, D. V., Anh, T. T. & Lam, N. T. Recovery of Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota (LcS) from the intestine of healthy Vietnamese adults after intake of fermented milk. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 26, 72–77 (2017).

Wang, R. et al. Survival of Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota in the intestines of healthy Chinese adults. Microbiol. Immunol. 59, 268–276 (2015).

Sakai, T. et al. M-RTLV agar, a novel selective medium to distinguish Lactobacillus casei and Lactobacillus paracasei from Lactobacillus rhamnosus. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 139, 154–160 (2010).

Matsumoto, K. et al. The effects of a probiotic milk product containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on the defecation frequency and the intestinal microflora of sub-optimal health state volunteers: A randomized placebo-controlled cross-over study. Biosci. Microflora 25, 39–48 (2006).

Nagata, S. et al. Effect of the continuous intake of probiotic-fermented milk containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on fever in a mass outbreak of norovirus gastroenteritis and the faecal microflora in a health service facility for the aged. Br. J. Nutr. 106, 549–556 (2011).

Nagata, S. et al. The effectiveness of Lactobacillus beverages in controlling infections among the residents of an aged care facility: A randomized placebo-controlled double-blind trial. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 68, 51–59 (2016).

Wang, C. et al. Intestinal microbiota profiles of healthy pre-school and school-age children and effects of probiotic supplementation. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 67, 257–266 (2015).

Nagao, F., Nakayama, M., Muto, T. & Okumura, K. Effects of a fermented milk drink containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on the immune system in healthy human subjects. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 64, 2706–2708 (2000).

Tamura, M. et al. Effects of probiotics on allergic rhinitis induced by Japanese cedar pollen: Randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 143, 75–82 (2007).

Gleeson, M., Bishop, N. C., Oliveira, M. & Tauler, P. Daily probiotic’s (Lactobacillus casei Shirota) reduction of infection incidence in athletes. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 21, 55–64 (2011).

Shida, K. et al. Daily intake of fermented milk with Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota reduces the incidence and duration of upper respiratory tract infections in healthy middle-aged office workers. Eur. J. Nutr. 56, 45–53 (2017).

Kushiro, A., Shimizu, K., Takada, T., Kusunoki, I. & Aiba, N. Decreased number of days of fever detection and duration of fever with continuous intake of a fermented milk drink: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of elderly nursing home residents. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health 38, 151–157 (2019).

Aoyagi, Y. & Shephard, R. J. Steps per day: The road to senior health?. Sports Med. 39, 423–438 (2009).

Aoyagi, Y. & Shephard, R. J. Habitual physical activity and health in the elderly: The Nakanojo Study. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 10, S236–S243 (2010).

Aoyagi, Y. & Shephard, R. J. A model to estimate the potential for a physical activity-induced reduction in healthcare costs for the elderly, based on pedometeraccelerometer data from the Nakanojo study. Sports Med. 41, 695–708 (2011).

Aoyagi, Y. & Shephard, R. J. Sex differences in relationships between habitual physical activity and health in the elderly: Practical implications for epidemiologists based on pedometer/accelerometer data from the Nakanojo Study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 56, 327–338 (2013).

Aoyagi, Y. et al. Habitual intake of fermented milk products containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota and a reduced risk of hypertension in older people. Benef. Microbes 8, 23–29 (2017).

Aoyagi, Y. et al. Independent and interactive effects of habitually ingesting fermented milk products containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota and of engaging in moderate habitual daily physical activity on the intestinal health of older people. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1447 (2019).

Endres, D. M. & Schindelin, J. E. A new metric for probability distributions. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 49, 1858–1860 (2003).

Chao, A., Chazdon, R. L., Colwell, R. K. & Shen, T.-J. A new statistical approach for assessing similarity of species composition with incidence and abundance data. Ecol. Lett. 8, 148–159 (2004).

Wilck, N. et al. Salt-responsive gut commensal modulates TH17 axis and disease. Nature 551, 585–589 (2017).

Chen, L. et al. Modest sodium reduction increases circulating short-chain fatty acids in untreated hypertensives: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Hypertension 76, 73–79 (2020).

Flint, H. J., Scott, K. P., Louis, P. & Duncan, S. H. The role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 9, 577–589 (2012).

Rinninella, E. et al. What is the healthy gut microbiota composition? A changing ecosystem across age, environment, diet, and diseases. Microorganisms 7, 14 (2019).

Kobayashi, Y., Tohyama, K. & Terashima, T. Studies on biological characteristics of Lactobacillus. II. Tolerance of the multiple antibiotic resistant strains, L. casei PSR3002, to artificial digestive fluids. Jpn. J. Bacteriol. 29, 691–697 (1974).

Bian, L. et al. Effects of the continuous intake of Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota-fermented milk on risk management of long-term inpatients at health service facilities for the elderly. Int. J. Probiot. Prebiot. 6, 123–132 (2011).

Kato-Kataoka, A. et al. Fermented milk containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota prevents the onset of physical symptoms in medical students under academic examination stress. Benef. Microbes 7, 153–156 (2016).

Kato-Kataoka, A. et al. Fermented milk containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota preserves the diversity of the gut microbiota and relieves abdominal dysfunction in healthy medical students exposed to academic stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 3649–3658 (2016).

Takada, M. et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota relieves stress-associated symptoms by modulating the gut–brain interaction in human and animal models. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 28, 1027–1036 (2016).

Morimoto, K., Takeshita, T., Nanno, M., Tokudome, S. & Nakayama, K. Modulation of natural killer cell activity by supplementation of fermented milk containing Lactobacillus casei in habitual smokers. Prev. Med. 40, 589–594 (2005).

Takeda, K. et al. Interleukin-12 is involved in the enhancement of human natural killer cell activity by Lactobacillus casei Shirota. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 146, 109–115 (2006).

Takeda, K. & Okumura, K. Effects of a fermented milk drink containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on the human NK-cell activity. J. Nutr. 137, 791S-793S (2007).

Suzuki, K. et al. Aberrant expansion of segmented filamentous bacteria in IgA-deficient gut. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 1981–1986 (2004).

Okai, S. et al. High-affinity monoclonal IgA regulates gut microbiota and prevents colitis in mice. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 16103 (2016).

Sugahara, H. et al. Decreased taxon-specific IgA response in relation to the changes of gut microbiota composition in the elderly. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1757 (2017).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 335–336 (2010).

Matsuki, T., Watanabe, K., Fujimoto, J., Takada, T. & Tanaka, R. Use of 16S rRNA gene-targeted group-specific primers for real-time PCR analysis of predominant bacteria in human feces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 7220–7228 (2004).

Arumugam, M. et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 473, 174–180 (2011).

Ihaka, R. & Gentleman, R. R: A language for data analysis and graphics. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 5, 299–314 (1996).

Kobayashi, M., Tsubono, Y., Sasazuki, S., Sasaki, S. & Tsugane, S. Vegetables, fruit and risk of gastric cancer in Japan: A 10-year follow-up of the JPHC study cohort I. Int. J. Cancer 102, 39–44 (2002).

Zhang, S., Tomata, Y., Sugiyama, K., Sugawara, Y. & Tsuji, I. Citrus consumption and incident dementia in elderly Japanese: The Ohsaki Cohort 2006 Study. Br. J. Nutr. 117, 1174–1180 (2017).

Aoyagi, Y. et al. Walking velocity measured over 5 m as a basis of exercise prescription for the elderly: Preliminary data from the Nakanojo Study. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 93, 217–223 (2004).

Shephard, R. J., Park, H., Park, S. & Aoyagi, Y. Objective longitudinal measures of physical activity and bone health in older Japanese: The Nakanojo Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 65, 800–807 (2017).

Shephard, R. J., Park, H., Park, S. & Aoyagi, Y. Objectively measured physical activity and progressive loss of lean tissue in older Japanese adults: Longitudinal data from the Nakanojo study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 61, 1887–1893 (2013).

Takahashi, K. et al. Validation of food frequency questionnaire based on food groups for estimating individual nutrient intake. Japanese J. Nutr. Diet. 59, 221–232 (2001) (in Japanese).

Heaton, K. W. et al. Defecation frequency and timing, and stool form in the general population: A prospective study. Gut 33, 818–824 (1992).

Anderson, M. J. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA). Wiley StatsRef Stat. Ref. Online 12, 1–15 (2017).

Gibson, K. M. et al. Gut microbiome differences between wild and captive black rhinoceros—implications for rhino health. Sci. Rep. 9, 7570 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This article focuses particularly on data from an interdisciplinary study on the habitual physical activity and health of elderly people living in Nakanojo, Gunma, Japan (the Nakanojo Study). We gratefully acknowledge the expert technical assistance of the research and nursing staff of the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology, the Yakult Central Institute, the University of Tokyo, and the Nakanojo Public Health Center. We thank the subjects whose conscientious participation made the Nakanojo Study possible.

Funding

This study was supported by Grants [Grant-in-Aid for Encouragement of Young Scientists: 12770037 and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C): 15500503, (C): 17500493, (B): 19300235, and (B): 23300259] from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and Grants from the Yakult Honsha Co. Ltd. and the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology. R.A., Ka.S., H.M., Ke.S., M.K., H.T. and S.M. are affiliated with the Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd., S.P. and Y.A. with the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology and R.S. with the University of Toronto.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.A.: study concept, assay of gut microbiota and preparation of manuscript. Ka.S., H.M., Ke.S., M.K., H.T., S.M.: assay of gut microbiota. S.P.: acquisition of subjects and data, analysis of data. R.S.: interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript. Y.A.: study concept and design, acquisition of subjects and data, analysis and interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained a repeated error in the Abstract, Introduction, the legend of Figure 4 and 5, the legend of Table 2, and in the Supplementary Information file, where “Lactocaseibacillus paracasei” now reads: “Lacticaseibacillus paracasei”.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amamoto, R., Shimamoto, K., Park, S. et al. Yearly changes in the composition of gut microbiota in the elderly, and the effect of lactobacilli intake on these changes. Sci Rep 11, 12765 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91917-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91917-6

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.