Abstract

The paper demonstrates an effective technique to significantly enhance the bandwidth and radiation gain of an otherwise narrowband composite right/left-handed transmission-line (CRLH-TL) antenna using a non-Foster impedance matching circuit (NF-IMC) without affecting the antenna’s stability. This is achieved by using the negative reactance of the NF-IMC to counteract the input capacitance of the antenna. Series capacitance of the CRLH-TL unit-cell is created by etching a dielectric spiral slot inside a rectangular microstrip patch that is grounded through a spiraled microstrip inductance. The overall size of the antenna, including the NF-IMC at its lowest operating frequency is 0.335λ0 × 0.137λ0 × 0.003λ0, where λ0 is the free-space wavelength at 1.4 GHz. The performance of the antenna was verified through actual measurements. The stable bandwidth of the antenna for |S11|≤ − 18 dB is greater than 1 GHz (1.4–2.45 GHz), which is significantly wider than the CRLH-TL antenna without the proposed impedance matching circuit. In addition, with the proposed technique the measured radiation gain and efficiency of the antenna are increased on average by 3.2 dBi and 31.5% over the operating frequency band.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Highly reliable and portable ultra-high frequency (UHF) wireless communication systems mainly employ monopole or dipole antennas. As the physical size of the antenna is proportional its operating wavelength, UHF-band antennas can have a length between 0.1 to 1 m. Various types of small UHF-band antennas have been previously proposed; however, they cannot be adapted for conformal installations and/or their bandwidth is limited1,2,3. Another method to reduce the antenna size is using metamaterials (MTMs) or left-handed (LH) (\(\varepsilon <0\), \(\mu <0\)) materials4,5,6. In practice, when creating a MTM the parasitic elements associated with transmission-lines (TLs), i.e. right-handed (RH) (\(\varepsilon >0\), \(\mu >0\)), combine with the LH characteristics to create a MTM structure commonly referred to as composite right/left-handed transmission-line (CRLH-TL)7. Antennas based on CRLH-TLs can be designed to operate in different modes, such as the zeroth-order resonance (ZOR) mode, + 1, and − 1 modes8,9. The zeroth-order resonance frequency makes CRLH-TLs independent of its physical dimensions. This property is taken advantage of here to miniaturize the antenna. As CRLH-TL can be easily realized using standard printed circuit board (PCB) technologies they have been used in the design of multiband antennas10, frequency reconfigurable antennas11 and pattern reconfigurable antennas8. However, the inherent narrow bandwidth of CRLH-TLs limits the range of applications of this type of antenna.

To overcome the bandwidth limitation of CRLH-TL antenna, it is necessary to introduce an active device that presents a negative reactance that counteracts the positive reactance of the antenna. This is achieved here with the use of a non-Foster impedance matching circuit. The challenging aspect of NF-IMC design is a stability-performance tradeoff, where instability leads to oscillation or latching. Optimal performance is achieved at the stability threshold, leaving little margin for error due to imperfect modeling, fabrication tolerances, and environmental changes. Numerous designs of the non-Foster circuit have been previously reported to realize wideband matching of electrically small antennas12,13,14,15. The improvement in the matching performance reported using NF-IMC is mainly in terms of reflection-coefficient, which does not completely characterize the antenna’s operational band.

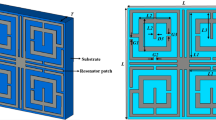

In this paper we demonstrate that by combining the proposed non-Foster impedance matching circuit (NF-IMC) with a narrowband CRLH-TL microstrip antenna it is possible to significantly enhance the antenna’s bandwidth and radiation gain performance without compromising its stability. This is due to the negative reactance created by the NF-IMC that is used to cancel the antenna’s high and positive reactance over its operating frequency range. The proposed antenna described here is implemented with six unit-cells of CRLH-TL, where the equivalent circuit of each unit-cell consists of series left-handed capacitance and shunt spiral left-handed inductance. The size of the proposed antenna is 56 \(\times \) 20 \(\times \) 0.8 mm3 or 0.261 \({\uplambda }_{0}\times \) 0.093 \({\uplambda }_{0}\times \) 0.003 \({\uplambda }_{0}\), where \({\uplambda }_{0}\) is at the minimum operation frequency of the antenna which is 1.4 GHz. The size of the non-Foster circuit is 0.074 \({\uplambda }_{0}\times \) 0.044 \({\uplambda }_{0}\) (16 \(\times \) 9.5 mm2). The proposed antenna has a measured bandwidth of > 1 GHz across 1.4–2.45 GHz for |S11|≤ − 18 dB, which is significantly wider than the CRLH-TL antenna without the non-Foster circuitry. With NF-IMC the measured antenna's radiation gain is shown to improve over its operating frequency range on average by approximately 3 dB.

Design of non-foster impedance matching circuit

Impedance matching circuits (IMCs) using conventional passive elements such as a LC-circuit are applicable only for narrowband devices. To circumvent this issue the negative impedance property of NF-IMC is exploited here to reverse the reactance slope of conventional LC-circuits, as illustrated in Fig. 1, to thereby accomplish impedance matching over a wider band. The design of the NF-IMC is based on the generic principle described in16 involving the use of cross-coupled transistors, as shown in Fig. 2a. This circuit is utilized here to convert the load impedance (Zref) seen by the two transistors to its negative equivalent. Positive feedback loop is created by cross coupling the gate and drain of the two transistors, which is typically used to design an oscillator circuit. Therefore, avoiding oscillations and ensuring stability are critical in the design of the NF-IMC. In the cross-coupled transistor arrangement the phase of the current at the input and output are identical, but there is a phase difference between the input and output voltages of 180°. From the small-signal model of the simplified NF-IMC topology in Fig. 2b, it can be shown that

where \({r}_{o}\) and \({g}_{m}\) are the transistor’s output resistance and transconductance, respectively. Assuming \({g}_{m}{r}_{o}\gg 1\) and is large compared to \({Z}_{ref}\), (1) can be approximated as \({Z}_{in}={-Z}_{ref}.\) The actual NF-IMC used in Fig. 2c was obtained through optimization using ADS from Keysight Technologies to provide impedance matching from 1.4 to 2.45 GHz. The optimized parameters of the NF-IMC are given in Table 1. Avago ATF-53189 transistor with an operating frequency of 50–6500 MHz was used here. The bias voltage VDD is 2 V.

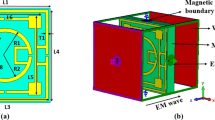

Active feedback is necessary in NF-IMC to realize the desired negative impedance. However, NF-IMCs can generate positive feedback when connected to the antenna system which can adversely affect its stability. As NF-IMC’s delicate stability is vulnerable to environmental changes, a small perturbation in antenna’s impedance could increase the positive feedback and make the NF-IMCs deviate from the stable condition into a large signal oscillator. It was therefore important to establish the stability of the NF-IMC. Stability over a wide band was achieved by cross coupling the transistors with series LC circuit. The stability was confirmed by checking impedance of the NF-IMC and the time domain transient response, as shown in Fig. 3. The stability was maintained by making the impedance of the non-Foster matching circuit smaller than the impedance of the antenna, which is confirmed in Fig. 3a over 1.4–2.45 GHz. Figure 3b shows the time domain transient response of the NF-IMC is stable after 0.2 microseconds of switching ‘on’ the NF-IMC.

Design of proposed CRLH-TL antenna

The equivalent circuit of a typical CRLH-TL unit-cell is constituted from a left-handed (LH) and right-handed (RH) circuitry7, where the LH circuit is composed of the series capacitors (\({C}_{L}\)) and the shunt inductors (\({L}_{L}\)). In practice, the unavoidable parasitic reactance elements are introduced in transmission-line structure, in particular series RH inductances (\({L}_{R}\)) and the parasitic shunt RH capacitances (\({C}_{R}\)) which compromise the existence of the purely LH circuit. The zeroth-order resonant frequency of the CRLH-TL is affected by these parasitic effects. Below the zeroth-order resonant frequency, CRLH-TL structure exhibits LH characteristics, and above zeroth-order resonant frequency, CRLH-TL exhibits RH characteristics. At the zeroth-order frequency, the resonant frequency is independent of the physical size. This property is exploited here to miniaturize the antenna. The zeroth-order resonant frequency is controlled by the series and shunt resonant frequencies defined by

The propagation constant (β) for a CRLH unit-cell is given by

where

Figure 4 shows the dispersion diagram of a typical CRLH-TL unit-cell when ωse and ωsh are unequal. At these resonant frequencies (ωse and ωsh) where β = 0, an infinite wavelength can be supported. According to the transmission-line theory CRLH-TL resonates at a frequency given by 7

where, l, n and N are the physical length of the resonator, mode number, and number of unit cells, respectively. When n is zero, the wavelength, λg = 2π/|βn|, becomes infinite and the resonant frequency of the zeroth-order mode becomes independent of the size of the resonator.

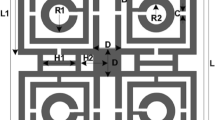

The antenna was designed by determining the reactance values in Eqs. (2) & (3) such that each of the two zeroth-order resonant frequencies define the boundary of the frequency range of interest. This was done by using the optimization tool in ADS by Keysight Technologies. The CRLH-TL unit-cell parameters were then converted to their physical implementation on microstrip technology, where \({C}_{L}\) is implemented by etching a spiral slot on a rectangular patch, and the \({L}_{L}\) is realized using a high impedance spiraled microstrip-line that is grounded with a metalized via-hole. The inductor was spiraled purely to minimize the spaced used. As mentioned earlier the parasitic RH elements (\({C}_{R}\) & \({L}_{R}\)) are unavoidable components in the transmission-line structure due to existence of the voltage gradient between the patch and ground plane, and the currents flowing on the surfaces, respectively13. As these parameters effect the overall frequency range of the antenna it was therefore necessary to optimize the structural parameters of the antenna unit-cell using ADS to realize the desired performance. The physical layout of the proposed antenna, which consists of a cascade of six unit-cells, and its equivalent circuit are shown in Fig. 5. The dispersion diagram of the CRLH-TL unit-cell depicted in Fig. 6 shows the LH and RH regions are 1.14 GHz < fLH < 1.41 GHz and 2.45 GHz < fRH < 3.6 GHz, respectively. It also shows the propagation constant of the CRLH-TL unit-cell is near zero in the frequency range of interest between 1.4 and 2.46 GHz. The simulation analysis in Fig. 7 reveals show the input impedance of the antenna is affected by the number of unit-cells. The antenna was implement using six unit-cells so that its impedance was compatible with the 50Ω NF-IMC board.

The proposed CRLH-TL antenna was constructed on the FR-4 lossy substrate with \({\varepsilon }_{r}\)=4.4, thickness h = 0.8 mm, and tan \(\delta \)=0.025. The equivalent circuit parameters of the CRLH-TL unit-cell were extracted using the pseudo-inverse method17 from the measured S-parameters. This involved converting the S-parameters to ABCD-parameters and the corresponding impedance and admittance from which the values of the lumped elements were obtained. The averaged values of the unit-cell parameters over the frequency of interest (1.4–2.45 GHz) are: \({L}_{L}=0.39 nH\), \({C}_{L}=6.12 pF\), \({L}_{R}=2.11 nH\), and \({C}_{R}=10.74 pF\). The structural parameters of the optimized antenna are given in Table 2, where \({\uplambda }_{0}\) is the free-space wavelength at 1.4 GHz.

The input capacitance of the antenna is approximated by \(Imag \left({Z}_{in}\right)=1/j\omega C\). The antenna’s input capacitance as a function of frequency is shown in Fig. 8. The input capacitance of the antenna was counteracted with the negative reactance generated by the NF-IMC and thereby overcome the inherent narrowband characteristic of the antenna.

Fabricated prototype and measurements

The fabricated prototype of the proposed antenna based on CRLH-TL is combined with the NF-IMC as shown in Fig. 9. An SMA male to SMA male coupler is used to connect the antenna to NF-IMC board. With the antenna connected to the NF-IMC board the measured reflection-coefficient is better than − 18 dB across 1.4–2.45 GHz, which corresponds to a fractional bandwidth of 54.54%. Simulated and measured reflection-coefficient responses of the proposed antenna before and after applying NF-IMC are shown in Fig. 10. Although there is reasonably good correlation between the simulated and measured results the large disparity between 1.4 to 1.5 GHz is attributed to the manufacturing tolerances and unaccounted mismatch with the SMA male to SMA male coupler.

The simulated and measured radiation gain and efficiency in the xy-plane (E-plane) of the proposed antenna before and after applying NF-IMC are shown in Fig. 11. There is good correlation between the simulated and measured results. It is evident from these results that with NF-IMC the measured radiation gain increases by 3.2 dBi from an average of 2.4 dBi to 5.6 dBi across 1.4–2.45 GHz. Over the same frequency span the measured radiation efficiency of the antenna increased by 31.5% from an average of 54.5% to 86%.

Figure 12 shows how the current density is distributed over the surface of the antenna at various frequencies in its operating frequency band. It reveals the magnitude of the current is strongest over the middle two and outer unit-cells. The measured 2D radiation patterns of the antenna in the xy-plane (E-plane) and xz-plane (H-plane) with and without NF-IMC at 1.4 GHz and 2.45 GHz are shown in Fig. 13. The antenna’s radiation energy is mainly focused in the x-direction. The beamwidth is much narrower in the xy-plane (E-plane).

The performance of the proposed CRLH-TL antenna with NF-IMC is compared with other state-of-the-art antennas reported in literature. The results of this study are summarized in Table 3. The main advantages of the proposed work are its simplicity and stability over a very wide (> 1 GHz) operating frequency range.

Conclusions

It has been shown that by incorporating a non-Foster impedance matching circuit (NF-IMC) in-line with a miniature antenna, which is based on composite right/left-handed transmission-line technology, the operating bandwidth and radiation gain of the antenna can be substantially enhanced without affecting the antenna’s stability. This is because the negative reactance generated by the NF-IMC is used to counteract the input capacitance of the antenna. The results presented demonstrate the effectiveness of this technique where the antenna’s bandwidth is shown to increase from 380 MHz to greater than 1 GHz. Moreover, by incorporating the NF-IMC the average radiation gain and efficiency are shown to improve by 3.2 dBi and 31.5% over its operating bandwidth.

References

Nandi, S. & Mohan, A. CRLH unit cell loaded quad-band monopole antenna. Microwave Opt. Tech. Lett. 58(3), 653–658 (2016).

Kim, S. & Lee, J. Frequency and bandwidth of the negative/positive nth mode of a composite right-/left-handed transmission line. J. Electromagn. Eng. Sci. 18, 1–6 (2018).

Nelaturi, S. & Sarma, N. A compact microstrip patch antenna based on metamaterials for WiFi and WiMAX application. J. Electromagn. Eng. Sci. 18, 182–187 (2018).

Yuan, Y. et al. Independent phase modulation for quadruplex polarization channels enabled by chirality-assisted geometric-phase metasurfaces. Nat. Commun. 11, 4186. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17773-6 (2020).

Zhang, K. et al. Polarization-engineered non interleaved metasurface for integer and fractional orbital angular momentum multiplexing. Laser Photon. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202000351 (2021).

Yuan, Y. et al. A fully phase-modulated metasurface as an energy-controllable circular polarization router. Adv. Sci. 7(18), 2001437. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202001437 (2020).

Caloz, C. & Itoh, T. Electromagnetic Metamaterials: Transmission Line Theory and Microwave Applications (Wiley-IEEE Press, 2005).

Zhang, J., Yan, S. & Vandenbosch, G. A. E. Realization of dual-band pattern diversity with a CRLH-TL-inspired reconfigurable metamaterial. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 66(10), 5130–5138 (2018).

Lee, H., Ren, D. & Choi, J. H. Dual-band and polarization-flexible CRLH substrate-integrated waveguide resonant antenna. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. 17(8), 1469–1472 (2018).

Gupta, A. & Chaudhary, R. K. ‘A miniaturized dual-band ZOR antenna using epsilon negative transmission line loading’. Int. J. Microw. Wireless Technol. 9(8), 1735–1739 (2017).

Khan, M. S. et al. A frequency-reconfigurable series-fed microstrip patch array with interconnecting CRLH transmission lines. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Letters 15, 242–245 (2016).

Shih, T.-Y. & Behdad, N. Wideband, non-Foster impedance matching of electrically small transmitting antennas. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 66(11), 5687–5697 (2018).

Kim, T.-H., Yun, G.-H., Lee, W. & Yook, J.-G. Highly efficient WPT system with negative impedance converter for Q-factor improvement. IEEE Access 7, 108750–108760 (2019).

White, C. R., Colburn, J. S. & Nagele, R. G. A non-Foster VHF monopole antenna. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 11, 584–587. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2012.2201129 (2012).

Go, J.-G. & Chung, J.-Y. Non-Foster matching circuit design to improve VHF and UHF-band small antenna impedance matching. J. Korean Inst. Electromagn. Eng. Sci. 29, 159–166 (2018).

Linvill, J. G. Transistor negative impedance converters. Proc. IRE 41(6), 725–729 (1953).

Kou, N., Shi, Y. & Li, L. New equivalent circuit analysis and synthesis for broadband composite right/left-handed transmission line metamaterials. ACES J. 31, 884–893 (2016).

Shi, T., Tang, M.-C., Wu, Z., Xu, H.-X. & Ziolkowski, R. W. Improved signal-to-noise ratio, bandwidth-enhanced electrically small antenna augmented with internal non-foster elements. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 67(4), 2763–2768 (2019).

Shen, Y. & Chio, T. Matching electrically small antenna using non-Foster circuit in the FM-band. The 8th Europ. Conf. on Ant. & Propag. (EuCAP 2014), The Hague, 2014, pp. 333–336.

Albarracín-Vargas, F. et al. Design method for actively matched antennas with non-Foster elements. IEEE Trans. Ant. Propag. 64(9), 4118–4123 (2016).

Zhang, T. et al. Unconditionally stable non-foster element using active transversal-filter-based negative group delay circuit. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Comp. Lett. 27(10), 921–923 (2017).

Batel, L., Pintos, J. & Rudant, L. Superdirective and broadband compact antenna array using non-Foster elements. Int. Workshop on Antenna Technology (iWAT), Miami, FL, USA, 2019, pp.17–20.

Jacob, M. M. et al. Non-Foster matched antennas for high-power applications. IEEE Trans. On Ant. Propag. 65(9), 4461–4469 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work is partially supported by RTI2018-095499-B-C31, Funded by Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, Gobierno de España (MCIU/AEI/FEDER,UE), and innovation programme under grant agreement H2020-MSCA-ITN-2016 SECRET-722424 and the financial support from the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) under grant EP/E022936/1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A., B.S.V., C.H.S., R.A.A.-A., F.F., I.H., T.A.D., and E.L.; methodology, M.A., B.S.V., F.F., I.H., T.A.D., and E.L.; software, M.A., B.S.V., and C.H.S.; validation, M.A., B.S.V., A.A.A., L.A., N.O.P., C.H.S., R.A.A.-A., F.F., I.H., T.A.D., and E.L.; formal analysis, M.A., B.S.V., C.H.S., R.A.A.-A., F.F., I.H., T.A.D., and E.L.; investigation, M.A., B.S.V., C.H.S., R.A.A.-A., F.F., I.H., T.A.D., and E.L.; resources, M.A., B.S.V., C.H.S., R.A.A.-A., F.F., I.H., T.A.D., and E.L.; data curation, M.A., B.S.V., A.A.A., L.A., N.O.P., C.H.S., R.A.A.-A., F.F., I.H., T.A.D., and E.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.; writing—review and editing, M.A., B.S.V., A.A.A., L.A., N.O.P., C.H.S., R.A.A.-A., F.F., I.H., T.A.D., and E.L.; visualization, M.A., B.S.V., C.H.S., R.A.A.-A., F.F., I.H., T.A.D., and E.L.; supervision, E.L.; project administration, R.A.A.-A., F.F., and E.L.; funding acquisition, R.A.A.-A., F.F, E.L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alibakhshikenari, M., Virdee, B.S., Althuwayb, A.A. et al. Bandwidth and gain enhancement of composite right left handed metamaterial transmission line planar antenna employing a non foster impedance matching circuit board. Sci Rep 11, 7472 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86973-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86973-x

This article is cited by

-

Circularly polarized printed dual port MIMO antenna with polarization diversity optimized by machine learning approach for 5G NR n77/n78 frequency band applications

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor and risk of heart failure in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

Scientific Reports (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.