Abstract

Changes in plant abiotic environments may alter plant virus epidemiological traits, but how such changes actually affect their quantitative relationships is poorly understood. Here, we investigated the effects of water deficit on Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) traits (virulence, accumulation, and vectored-transmission rate) in 24 natural Arabidopsis thaliana accessions grown under strictly controlled environmental conditions. CaMV virulence increased significantly in response to water deficit during vegetative growth in all A. thaliana accessions, while viral transmission by aphids and within-host accumulation were significantly altered in only a few. Under well-watered conditions, CaMV accumulation was correlated positively with CaMV transmission by aphids, while under water deficit, this relationship was reversed. Hence, under water deficit, high CaMV accumulation did not predispose to increased horizontal transmission. No other significant relationship between viral traits could be detected. Across accessions, significant relationships between climate at collection sites and viral traits were detected but require further investigation. Interactions between epidemiological traits and their alteration under abiotic stresses must be accounted for when modelling plant virus epidemiology under scenarios of climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As sessile organisms, plants are continuously exposed to combinations of abiotic and biotic stresses1. In response to these constraints, plants have evolved specific mechanisms to detect environmental changes and respond to complex stress conditions, minimizing damage while maintaining valuable resources for growth and reproduction2,3. Soil water deficit (WD) and virus infection are two important factors impacting plant performance that frequently occur simultaneously in natural conditions4,5.

Viruses are obligate parasites and, as such, cannot complete their life cycle without exploiting a suitable host. Hence, the success of viral infection depends on the physiological machinery of the host plant, and thus any environmental change that affects plant physiology—mostly through alteration of host signaling pathways—may also affect viral infection outcomes6. Thus, in the context of climate change, recent studies have focused on important viral life traits (e.g. accumulation, virulence, vectored-transmission rate) in the tripartite plant-vector-pathogen interaction field7,8,9,10.

Virulence, defined here as the degree of damage caused to a susceptible host plant, may be affected by environmental factors such as air temperature, edaphic water availability, and atmospheric CO210,11,12. Specific environmental conditions can also modulate virulence in such a way that viral infection is positively correlated with host fitness13,14,15,16,17,18,19. We have also shown recently that virulence can increase under water deficit20.

The contrasting effect of abiotic stresses on viral accumulation through the hijacking of plant signaling and defense pathways has received much recent attention11,21,22,23. For instance, while Barley yellow dwarf virus titer increases by more than 30% in wheat grown under elevated atmospheric CO2 (eCO2) or elevated temperature22,24, titers of Soybean mosaic virus or Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) are negatively impacted in plants grown under water deficit10,25. However, no clear trends were described between viral accumulation and virulence under these challenging conditions.

Most plant viruses rely on arthropods to spread, with aphids being by far the most widespread vectors26. Virus acquisition from an infected plant, virus retention, and virus inoculation to a new plant are critical steps that mediate the success of the infection27. Virus transmission efficiency depends not only on the intrinsic strategy of the virus and vector behavior, but also on the physiological status of the host plant, the environment, and thus on tripartite plant-vector-pathogen interactions28,29,30. For example, vectored-transmission of CaMV and Turnip mosaic virus increased significantly when Brassica rapa source plants experienced a severe water deficit31. The same abiotic stress applied to Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh (Col-0 accession) infected with Turnip yellows virus, drastically reduced transmission efficiency, likely due to an altered feeding behavior of the aphid vector32.

The viral traits discussed above are expected to interact tightly, allowing successful coevolution of hosts and pathogens, as originally described through the trade-off hypothesis33,34. This hypothesis predicts the existence of an optimal level of virulence that integrates the benefits of transmission and the cost of killing the host and, so for, relies on two key assumptions: (1) a positive correlation between accumulation and transmission, and (2) a positive correlation between accumulation and virulence33,35. While the first assumption has been demonstrated for several vector-borne plant viruses, the latter remains controversial36,37,38,39. Overall, available data do not allow a prevailing correlation between these three viral traits in plant viral pathosystems to be confirmed or refuted35,40. Moreover, data on how these different viral traits would interact in a disturbed environment are scarce.

In a previous study, we have shown that water deficit altered the relationship between transmission rate and virulence of CaMV in A. thaliana10. However, the restricted number of accessions assessed precluded analysis of other viral trait relationships that may help explain the transmission–virulence trade-off.

Here, we examined the effect of an edaphic water deficit on viral traits when A. thaliana plants were infected with CaMV. Relationships between virulence, as quantified by the relative change in aboveground dry mass, accumulation and aphid transmission, were analyzed under both well-watered and water deficit conditions. We quantified these viral traits in a set of 24 natural A. thaliana accessions originating from the Iberian Peninsula for the following reasons: (1) this region is characterized by a wide range of climatic conditions, notably in terms of annual precipitation, and (2) CaMV has been found to infect natural populations of A. thaliana41. These accessions were grown under strictly controlled environmental conditions in the high-throughput phenotyping platform PHENOPSIS42. We previously demonstrated a significant variation in CaMV virulence among these specific A. thaliana accessions that was not related to climatic variables, specifically annual precipitation, of original local populations10,20. Here, we explicitly tested the trade-off hypothesis, namely that virulence is positively related to vectored-transmission rate whatever the conditions of water availability and discuss the observed relationships between viral traits and climatic variables.

Results

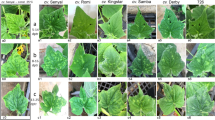

The CaMV isolate Cabb B-JI successfully infected plants from all 24 A. thaliana accessions grown in two independent experiments, regardless of watering treatment. Infected plants showed characteristic symptoms of a CaMV infection: chlorotic lesions, vein-clearing and crinkled rosette leaves.

Changes in viral traits under water deficit

For each of the 24 accessions of the A. thaliana plant species, we determined vegetative growth, virulence (expressed as reduction of aboveground rosette dry mass), viral accumulation and transmission efficiency by aphids in CaMV-source plants under well-watered (WW) and water deficit (WD) treatments. Under well-watered conditions, mean aboveground dry mass of mock-inoculated (± se) ranged from 500 ± 40 mg (Per-0) to 1087 ± 50 mg (Mat-0) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). CaMV infection induced a reduction in vegetative growth in all A. thaliana accessions (Figs. 1, 2A; P < 0.001, Supplementary Table S2). Moreover, a highly significant variation in accession responses to CaMV infection and WD was found (Figs. 1, 2), as indicated by a significant interactive effect between accession and inoculation, and between accession and watering (Supplementary Table S3; P = 0.013 and P = 0.021, respectively). Under the WW treatment, CaMV virulence varied greatly, with some accessions exhibiting less than 11.1 ± 8.8% reduction in vegetative growth (Piq-0), while in the most CaMV-susceptible accessions vegetative growth decreased up to 60.1 ± 5.7% (Ini-0) (–38% on average across accessions; Fig. 2A). As expected from Fig. 1, the combination of viral infection and WD was even more detrimental to vegetative growth of all accessions (–58% on average across accessions; Fig. 2A).

Effects of CaMV infection and watering treatment on vegetative growth of 24 A. thaliana accessions. Bars are mean ± 95% CI of rosette dry mass (mg) at 30 dpi of plants grown under well-watered (WW) and water deficit (WD) treatments: mock-inoculated:WW (white bars; n = 4), mock-inoculated:WD (dark grey bars; n = 4), CaMV-infected:WW (light grey bars; n = 15) and CaMV-infected:WD (black bars; n = 15) treatments. Data are from Experiment 1 and 2 (experiment 1, n = 13; experiment 2, n = 12 accessions). Different letters indicate a significant difference between treatments for each accession. Accessions are ordered alphabetically by experiment from Bla-1 to Sf-2 (experiment 1) and from Ala-0 to Vad-0 (experiment 2). Col_E1: Col-0 of experiment 1 and Col_E2: Col-0 of experiment 2.

source plants (n = 11 per accession and per treatment). (C) Transmission rate, i.e., mean proportion of infected receptor plants (n = 9 receptor plants per source plant, 11 source plants per accession and per treatment). Data are from experiment 1 and 2 (experiment 1, n = 13; experiment 2, n = 12 accessions). Accessions are ordered by virulence level under well-watered conditions. Bars and error bars are means ± se of plant grown under CaMV-infected:WW (light gray bars) and CaMV-infected:WD (black bars) treatments at 30 dpi. (A), all differences between watering treatments are significant but Bea-0 (n.s.: not significant). (B, C), statistically significant differences between watering treatments for each accession following Wilcoxon test are indicated (*: P < 0.05; : P < 0.10).

CaMV traits of A. thaliana accessions under well-watered (WW) and water deficit (WD) treatments. (A) CaMV virulence determined as vegetative growth reduction (%) (n = 15; per accession and per treatment). (B) CaMV-accumulation in

For instance, vegetative growth decreased from 43.5 ± 3.8% in Piq-0 to 74.0 ± 1.5% in Ini-0 (Fig. 2A). Bea-0 was the only accession that exhibited a similar reduction of vegetative growth under both watering conditions (Fig. 2A). Noticeably, variation of aboveground dry mass between accessions was significantly lower under WD than under WW (among-accession coefficient of variation = 31% under WW vs. 13% under WD; statistic of signed-likelihood ratio test = 107.8; P < 0.001). A positive and significant rank correlation between virulence under WW treatment and virulence under WD treatment was found (⍴ = 0.63, P = 0.001; Fig. 3A). Thus, WD did not significantly affect the ranking of A. thaliana accessions according to CaMV virulence.

Effect of water deficit on CaMV traits in A. thaliana accessions. Relationships between mean values of (A) CaMV virulence (expressed as the % of vegetative growth reduction). (B) CaMV accumulation (N0 CaMV / N0 UBC21_Actin) or (C) transmission rate (%) under well-watered (WW) and water deficit (WD) treatments. Dashed lines represent 1:1 line, and solid lines represent significant linear regressions. Spearman’s correlation coefficients and associated P values are reported for each trait.

Viral accumulation estimated by qPCR varied greatly among accessions whatever the watering treatment (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Table S4). CaMV accumulation was 20-fold higher in Lch-0 than in Ala-0 accession when plants grew under WW conditions, while a fourfold CaMV accumulation difference was measured between Fei-0 and Lam-0 accessions in the WD treatment (Fig. 2B). Under WD, viral accumulation increased significantly, or marginally significantly, in seven accessions (Ini-0, Sfb-6, Ala-0, Bea-0, Lam-0, P < 0.05; Mat-0, Cdm-0, P < 0.10), while it decreased significantly in three others (Lch-0, Orb-10 and Ovi-1, P < 0.05) (Fig. 2B). Contrary to what was observed in virulence analyses, no correlation between viral accumulation under WW and under WD treatments was detected (r = –0.10, P = 0.66; Fig. 3B).

Under WW conditions, transmission rate varied from 26.3 ± 3.8% to 56.9 ± 4.2% (Sf-2 and Col-0, respectively) (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Table S5). Under WD, transmission rate varied also in a similar range (22.2 ± 5.2–58.5 ± 3.7% for Lam-0 and Can-0, respectively) (Fig. 2C). A significant and positive relationship between transmission rate under WW and WD treatments was detected (r = 0.58, P = 0.003; Fig. 3C). Thus, an accession for which CaMV transmission was high under WW showed also a high transmission efficiency under WD (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, a significant alteration of the transmission rate when source plants were subjected to WD was observed in four accessions. The transmission rate increased significantly in Can-0 (from 41 to 59%; P = 0.004) and Ini-0 (29% to 45%; P = 0.009), while it decreased significantly in Bos-0 (from 50 to 39%; P = 0.044) and Lam-0 (from 33 to 22%; P = 0.049) in response to the WD treatment (Fig. 2C).

Water deficit changes relationships between viral traits

Under WW conditions, a significant and positive correlation was found between viral accumulation and CaMV transmission rate (⍴ = 0.49, P = 0.016; Fig. 4A). Under this watering treatment, no significant rank correlation between viral accumulation and CaMV virulence could be detected (⍴ = 0.15, P = 0.481; Fig. 4B). No significant correlation between CaMV virulence and viral transmission was also found under WW treatment (⍴ = 0.13, P = 0.531; Fig. 4C). Changes in viral traits in response to WD across accessions (Fig. 2) led to an alteration of the relationships between these traits. Specifically, the correlation between viral accumulation and CaMV transmission was significantly reversed under WD (⍴ = –0.46, P = 0.024; Fig. 4D). As observed in the WW treatment, no correlation between CaMV virulence and viral accumulation (⍴ = 0.03, P = 0.872; Fig. 4E), or between virulence and viral transmission (⍴ = − 0.06, P = 0.776; Fig. 4F), was observed.

Relationships between CaMV traits in A. thaliana accessions under two contrasting watering regimes. Relationships between CaMV virulence on vegetative growth, transmission rate and accumulation under well-watered (A–C) and water deficit (D–F) conditions. Solid lines represent significant linear regressions. Spearman’s correlation coefficients and associated P values are reported for each relationship.

Relationships between viral traits and biogeographic origin of accessions

Correlations between climate at the collection sites of the accessions and viral traits were investigated (Supplementary Fig. S1). CaMV virulence was significantly positively correlated to isothermality—defined as the ratio of mean diurnal range of temperature (mean of monthly(max. temp—min. temp)) and temperature annual range—under WW, and positively, but not significantly, under WD (WW: r = 0.50, P = 0.04; WD: r = 0.27, P = 0.21; Supplementary Fig. S1). Viral accumulation under WW was significantly negatively correlated with precipitation seasonality, i.e. the coefficient of variation of monthly precipitations (WW: r = –0.43, P = 0.04; Supplementary Fig. S1). Virus accumulation under WD was significantly negatively correlated with isothermality (WD: r = –0.51, P = 0.014; Supplementary Fig. S1). Viral transmission was significantly correlated to isothermality only under WD conditions (WD: r = 0.42, P = 0.046; Fig. S1).

Discussion

In a previous independent study, we showed that water deficit altered the transmission-virulence trade-off in the CaMV-A. thaliana pathosystem10. However, due to the restricted number of A. thaliana accessions, we were unable to test two key assumptions of the transmission-virulence trade-off hypothesis: (1) correlation between accumulation and transmission, and (2) correlation between accumulation and virulence. Here, we measured CaMV accumulation, virulence on vegetative growth and transmission rate by the aphid M. persicae in 24 natural Iberic accessions of A. thaliana presenting a large genetic variability and grown under two contrasting watering treatments43. To reflect variable plant responses levels to water deficit and, potentially, to virus infection, we selected the 24 natural accessions of A. thaliana from a large variety of climatic regions and altitudes distributed evenly across the Iberian Peninsula44. Significant relationships between climate parameters (isothermality, temperature and precipitation patterns and seasonality) and viral traits were detected depending of the watering treatment. Climatic conditions are frequently identified as factors of local adaptation of plant species. In A. thaliana, climatic factors have been found to be significantly associated to several traits, including flowering phenology, growth and functional strategies45,46,47, as well as genomic regions associated with regulation of gene expression, especially at regional and micro-geographic scales48,49. Contrary to a study by Montes and colleagues9, where no relationship between Cucumber mosaic virus viral accumulation and climatic variables from the original local populations could be detected, CaMV viral accumulation under well-watered conditions was significantly negatively correlated with precipitation seasonality while under WD, a negative correlation was detected between viral accumulation and isothermality. Interestingly, vectored-transmission was positively correlated to isothermality when plants were submitted to a WD. Under WD, CaMV accumulation within low temperature fluctuations environment-accessions was reduced while vectored-transmission would be higher than in other accessions. These relationships may result from the interrelationships between local climate conditions, occurrence of selective pathogens and the functional strategies of the plant genotypes9,20. The adaptive value of these relationships will require further investigations combining experiments under field and controlled conditions.

Plant signaling pathways and responses to various abiotic stresses partly overlap those induced by viral infection, and their mutual interference is not a novel concept. Indeed, the effect of abiotic plant stresses on viral accumulation and virulence through the hijacking of plant signaling and defense pathways has received recent attention21,22,50. In accordance with previous results20, we showed here that application of a water deficit to CaMV-infected A. thaliana leads to higher virulence, and was overall more detrimental to plant performance compared with virulence under well-watered condition regardless of accession. Under WD, CaMV accumulation was altered in 10 accessions; in most cases there was a significant increase of this viral trait. While a negative (or no) effect of WD on viral accumulation has already been shown in several viral pathosystems10,25,31,32, to our knowledge, such a positive effect on virus accumulation has not previously been reported.

In the context of climate change, a number of studies have investigated vectored-transmission in contrasted abiotic environments [for review see51]. WD applied to CaMV-source plants did not significantly impact CaMV transmission rate, except in four accessions. In these four accessions, WD had a contrasted effect on the transmission success, linked to the accession origin. While CaMV transmission by the aphid M. persicae increased in Can-0 and Ini-0 accessions under water deficit, it decreased in Bos-0 and Lam-0 accessions.

A positive correlation between CaMV transmission rate and accumulation was observed, which had not been detected when using fewer accessions10. This discrepancy might be explained by the different growing conditions (8-h vs. 12-h day length) used in the two studies. The positive correlation between CaMV transmission rate and accumulation observed here, and already shown in other pathosystems, might reflect the fact that a high availability of virus particles within plant cells increases the chance of acquisition by the vector37,52. However, in this study, factors other than accumulation might also explain alteration of virus transmission when plants experienced a water deficit. Indeed, in the specific case of Can-0 accession, which exhibited a significant increase of CaMV transmission under WD, accumulation did not seem to be the limiting factor as virus accumulation remained stable whatever the watering treatment. This observation was supported by the inverse relationship between CaMV transmission and virus accumulation under WD. As a result, plants with a lower virus content became significantly better source plants for vectored-transmission under WD. A lack of positive correlation between accumulation and transmission rate has already been shown in CaMV-infected B. rapa source plants experiencing severe WD31. The significant increase in transmission rate was suggested to be due to a change in host plant physiological status that could trigger a direct effect on virus behavior53,54. As a consequence, these rapid changes in virus behavior may actually predisposes the infected plant to a more efficient virus acquisition and transmission by aphid vectors53,54. This remarkable phenomenon has been termed ‘transmission activation’ and can be triggered by abiotic stresses such as CO2 treatment55.

We were unable to find any other relationship between viral traits. Unsuccessful validation of the trade-off hypothesis—i.e. a negative correlation between virulence and transmission—might be explained by the fact that one of the two required assumptions of this trade-off—i.e. a positive correlation between accumulation and virulence—was not demonstrated in our model system. Moreover, the trade-off hypothesis is an adaptive hypothesis that supposes a common evolutionary history between the host and the pathogen, suggesting efficient development of the parasite without harming the host35. Indeed, with the rise of metagenomics, sequence data collected in natura confirm that most virus-infected plants are asymptomatic56. Also, it is important to note that, in our system, the virus isolate did not co-evolve with these specific plant accessions even though several other CaMV isolates are reported to infect natural A. thaliana populations in Spain41. The isolate CaMV Cabb B-JI was originally isolated from B. rapa and fixed by cloning the genome sequence57. Moreover, the trade-off hypothesis, which assumes a simplified biology where virulence and transmission of the parasite are independent of the characteristics of the host, remains controversial58. In fact, viral traits are the result of multiple interactions within the host, such as immune responses to counteract the development of infection.

In conclusion, our results reaffirm that water deficit might have substantial effects on key viral traits, with epidemiological consequences for plant viral disease. The multi-faceted relationships between virulence, viral accumulation and vectored-transmission according to the environmental conditions experienced by the host invite further investigation.

Methods

Experimental design and A. thaliana growth treatments

We selected 24 natural accessions of A. thaliana originating from the Iberian Peninsula sequenced by Carlos Alonso-Blanco and collaborators and belonging to four distinct genetic lineages as determined by the 1001 genomes Project (S2 Fig, Supplementary Table S6) (http://1001genomes.org/))44. These accessions were grown in two independent experiments (experiment 1, n = 13; experiment 2, n = 12; Col-0 accession in common), under combinations of well-watered (WW), water deficit (WD), CaMV-inoculation (CaMV) and mock inoculation (Mock) treatments. Plants were analyzed in four treatments: Mock:WW (n = 4 plants per accession), Mock:WD (n = 4), CaMV:WW (n = 15) and CaMV:WD (n = 15) in each independent experiment.

Experiments were conducted in the PHENOPSIS facility. This phenotyping platform allows automated watering, weighing and imaging of 504 potted plants under strictly controlled environmental conditions42. Three to five seeds were sown at the soil surface in 225-ml pots filled with a 30:70 (v/v) mixture of clay and organic compost (substrate SP 15% KLASMANN) and placed randomly in the PHENOPSIS growth chamber. Soil water content was estimated for each pot before sowing, as previously described42. The soil surface was moistened with deionized water, and pots were placed in the dark for 2 days at 12 °C air temperature and 70% air relative humidity. Pots were dampened with sprayed deionized water three times a day until germination. After the germination phase (ca. 7 days), plants were cultivated under 12-h day length at 200 μmol m–2 s–1 photosynthetic photon flux density at plant height. Air temperature was set to 20 °C, and air relative humidity was adjusted in order to maintain constant water vapor pressure deficit at 0.6 kPa. At the appearance of the cotyledons, one plant was kept per pot, and the temperature was set at 21/18 °C day/night, while the vapor pressure deficit was set at 0.75 kPa. Each pot was weighed daily and watered with deionized water to reach the target soil relative water content. Soil relative water content was maintained at 1.4 g H2O g–1 dry soil (WW) until application of the treatments. CaMV- or mock-inoculation (see below) was performed at the emergence of the tenth rosette leaf. WD was applied 1 week after inoculation—the approximate timing of first symptom appearance. Irrigation of half of the CaMV- and mock-inoculated plants was stopped to reach WD treatment at 0.50 H2O g–1 dry soil, reached after 7 days of water deprivation, and then maintained at this value until the end of the experiment. Under WW, soil relative water content was maintained at 1.4 g H2O g–1 dry soil. All environmental data, including daily soil water content, air temperature, and vapor pressure deficit, are available in the PHENOPSIS database59.

Virus purification and mechanical inoculation of source plants

The CaMV isolate Cabb B-JI—a non-circulative aphid-transmitted virus—was used in this study57. Virus particles were purified from CaMV-infected Brassica rapa cv. “Just Right” (turnip) plants as previously described60. The quality and quantity of purified virus were assessed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under denaturing treatments (12% SDS-PAGE) and by spectrometric measurements at 230, 260, and 280 nm (NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer). Virus concentration was estimated by spectrometry using the formula described by Hull and Shepherd60. At the 10-leaf stage, A. thaliana source plants were mechanically inoculated as previously described10. Briefly, CaMV-infected turnip extract was prepared from 1 g of infected leaf material [turnip leaves presenting systemic symptoms collected at 21 days post inoculation (dpi)] ground in 1 mL of distilled water with carborundum. Purified CaMV particles were then added to this mix at a final concentration of 0.2 mg mL–1 to optimize infection success. For each inoculated plant, 10 μL of the solution described above was deposited on each of three middle-rank leaves. Leaves were then rubbed with an abrasive pestle. The control group was mock-inoculated in a similar way to mimic the wounds induced by mechanical inoculation. Mock-inoculation was performed with a mix containing non-infected turnip plant extract and the buffer used for virus purification (100 mM Tris–HCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, pH 7). All plants were randomly inoculated, independently of accession and watering regime.

Measurement of plant traits

Harvests were carried out at 30 dpi following transmission experiments (see below). Each rosette was cut, fresh mass was measured then the tissue was kept in deionized water for 24 h at 4 °C to determine the water-saturated weight (mg). Collected rosettes were subsequently oven-dried at 65 °C for at least 5 days, and their dry masses determined.

Virulence, described as the impact of CaMV infection on vegetative growth61, was estimated for each accession as the relative change of mean aboveground dry mass (ADM) of the rosette as: (ADMCaMV:WW – ADMMock:WW)*100 /ADMMock:WW) and (ADMCaMV:WD – ADMMock:WW)*100 /ADMMock:WW).

Aphid rearing

The colony of the aphid-vector species Myzus persicae, collected over 30 years ago in the south of France, was maintained on eggplants (Solanum melongena) in insect-proof cages, in a growth chamber at 24/19 °C with a photoperiod of 14/10 h (day/night), ensuring clonal reproduction (G. Labonne, pers.comm.). Aphids were transferred to new cages and to new non-infested host plants (S. melongena) every 2 weeks, in order to avoid overcrowding and induction of the development of winged morphs.

Transmission assays

CaMV transmission efficiency was assessed at 30 dpi. Batches of 20 M. persicae larvae (L2–L4 instars) were starved for 1 h before being transferred to the rosette center of a CaMV-mechanically infected source plant for virus acquisition; 11 symptomatic mechanically infected source plants were used per accession and watering treatment. When aphids stopped walking and inserted their stylets into the leaf surface, they were allowed to feed for a short 2-min period. Viruliferous aphids were then immediately collected in a Petri dish and individually transferred to 1-month-old Col-0 plantlets (receptor plants) grown under non-stressing treatments (one aphid per receptor plant; nine receptor plants per source plant) as described10. After an inoculation period of 3 h, aphids were eliminated by insecticide spray (0.2% Pirimor G). Receptor plants were then placed in a growth chamber with the same treatments of air humidity, temperature and light as source plants and maintained under non-stressing conditions. Symptoms of virus infection were recorded 21 days later by visual inspection on receptor plants, following the procedure previously reported10 and virus transmission rate was then calculated. Following transmission experiments, three leaf discs in the center of the rosette were randomly collected on each mechanically infected source plant and stored at – 80 °C for further nucleic acid extraction and virus quantification.

Plant DNA extraction

Total DNA from CaMV-infected samples (pool of three leaf discs collected per plant) was extracted according to a modified Edwards’ protocol with an additional washing step with 70% ethanol62. DNA was resuspended in 50 μL of distilled water, and ten-fold dilutions were used as qPCR templates. Quality and quantity of the extracted total nucleic acid were assessed by spectroscopic measurements at 230, 260 and 280 nm (NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer).

Viral accumulation

CaMV DNA quantification (11 biological replicates per accession and treatment) was performed in duplicate by qPCR in 384-well optical plates using the LightCycler FastStart DNA Master Plus SYBRGreen I kit (Roche) in a LightCycler 480 (Roche) thermocycler according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Specific primers designed for quantification of the CaMV genome (Ca4443-F: 5′-GACCTAAAAGTCATCAAGCCCA-3′ and Ca4557-R: 5′-TAGCTTTGTAGTTGACTACCATACG-3′) and two housekeeping genes: A. thaliana ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme 21 gene (UBC21; GenBank accession DQ027035; UBC21_At_F: 5′-TGCAACCTCCTCAAGTTCGA-3′ and UBC21_At_R: 5′-GCAGGACTCCAAGCATTCTT-3′) and A. thaliana Actin gene (GenBank accession GQ339782.1; F-Act2: 5′-GACYBTAYGGTAACATTGTGCTC-3′ and R-ActBra: 5′-GATCTCTTTGCTCATACGGTCTG-3′) were used at a final concentration of 0.3 μM. All qPCR reactions were performed with 40 cycles (95 °C for 15 s, 62 °C for 15 s and 72 °C for 15 s) after an initial step at 95 °C for 10 min. The qPCR data were analyzed with the LinReg PCR program to account for the efficiency of every single PCR reaction63. The absolute initial viral concentration in A. thaliana plants, expressed in arbitrary fluorescence units (N0 CaMV) was divided by that of A. thaliana UBC21 and Actin genes, in order to normalize the amount of plant material analyzed in all samples.

Data analyses

All analyzes were performed in the programming environment R64. Variations of vegetative growth (aboveground dry mass), viral accumulation and transmission rate among accessions in response to virus infection and watering treatment were analyzed in both parametric (type III) and non-parametric (rank-based) ANOVAs. Non-parametric procedure was used because of unbalanced sampling across factor levels and risks of deviation from Normality and heteroscedasticity. Data of the two experiments were analyzed together since no significant interactive or main effect of experiment was found for aboveground dry mass, viral accumulation, and viral transmission of the control accession Col-0 (Supplementary Table S7). For each accession, the effects of the treatments on traits were analysed by non-parametric tests for two (Wilcoxon) or more (Kruskal–Wallis) samples. For each accession, relative change was calculated as the ratio of the difference between the trait value of each replicate plant and mean trait value under control conditions (mock:well-watered) to the mean trait value under control conditions. Non-parametric ANOVAs were performed using the raov function of the Rfit package65. Bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (CI) of mean trait values were computed following the mean_cl_boot procedure of the Hmisc package66. We used the R package cvequality (Version 0.1.3)67 to test for significant differences between coefficients of variation. Nonlinear models were fitted using the nls function and 95% confidence intervals for the parameters of fitted models were computed with the confint function of the package mass68. The effect of watering on transmission rate was analyzed using generalized linear models with the binomial model in the glm function of the stat package applied to the proportion of infected and uninfected plants in the transmission assays. Relationships between traits were examined with Spearman’s rank-order coefficients of correlation (⍴) using the function cor.test. Relationships between traits and climate at the collection sites of the accessions (obtained from WorldClim v. 1.4, http://worldclim.org)69 were examined in generalised least squares models in order to take spatial autocorrelation into account. First, we tested the bivariate relationships between traits and climatic variables, then we added a Gaussian autocorrelation structure to the model. Pearson’s correlation coefficients are reported with GLS P values.

Statement on experimental research on plants

Seeds used in the present study were obtained with permission from Rebecca Schwab and Detlef Weigel (Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tuebingen, Germany) and comply with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

References

Rejeb, I. B., Pastor, V. & Mauch-Mani, B. Plant responses to simultaneous biotic and abiotic stress: Molecular mechanisms. Plants (Basel) 3, 458–475. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants3040458 (2014).

Pandey, P., Ramegowda, V. & Senthil-Kumar, M. Shared and unique responses of plants to multiple individual stresses and stress combinations: Physiological and molecular mechanisms. Front. Plant. Sci. 6, 723. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00723 (2015).

Zhang, H. & Sonnewald, U. Differences and commonalities of plant responses to single and combined stresses. Plant J. 90, 17 (2017).

Szczepaniec, A. & Finke, D. Plant-vector-Pathogen interactions in the context of drought stress. Front. Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2019.00262 (2019).

Jones, R. A. Plant virus emergence and evolution: Origins, new encounter scenarios, factors driving emergence, effects of changing world conditions, and prospects for control. Virus Res. 141, 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2008.07.028 (2009).

Pallas, V. & Garcia, J. A. How do plant viruses induce disease? Interactions and interference with host components. J. Gen. Virol. 92, 2691–2705. https://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.034603-0 (2011).

Chung, B. M. et al. The effects of high temperature on infection by potato virus Y, potato virus A, and potato leafroll virus. Plant Pathol. J. 32, 321–328. https://doi.org/10.5423/PPJ.OA.12.2015.0259 (2016).

Del Toro, F. J. et al. Ambient conditions of elevated temperature and CO2 levels are detrimental to the probabilities of transmission by insects of a Potato virus Y isolate and to its simulated prevalence in the environment. Virology 530, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2019.02.001 (2019).

Montes, N., Alonso-Blanco, C. & Garcia-Arenal, F. Cucumber mosaic virus infection as a potential selective pressure on Arabidopsis thaliana populations. PLoS Pathog. 15, 24. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1007810 (2019).

Bergès, S. E. et al. Interactions between drought and plant genotype change epidemiological traits of cauliflower mosaic virus. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 703. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.00703 (2018).

Aguilar, E. et al. Effects of elevated CO2 and temperature on pathogenicity determinants and virulence of potato virus X/potyvirus-associated synergism. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 28, 1364–1373. https://doi.org/10.1094/MPMI-08-15-0178-R (2015).

Chung, B. N. et al. Effects of temperature on systemic infection and symptom expression of turnip mosaic virus in Chinese cabbage (Brassica campestris). Plant Pathol. J. 31, 363–370. https://doi.org/10.5423/PPJ.NT.06.2015.0107 (2015).

Pagan, I., Alonso-Blanco, C. & Garcia-Arenal, F. The relationship of within-host multiplication and virulence in a plant-virus system. PLoS ONE 2, e786. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0000786 (2007).

Xu, P. et al. Virus infection improves drought tolerance. New Phytol. 180, 911–921. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02627.x (2008).

Westwood, J. H. et al. A viral RNA silencing suppressor interferes with abscisic acid-mediated signalling and induces drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant Pathol. 14, 158–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1364-3703.2012.00840.x (2013).

Aguilar, E. et al. The P25 protein of potato virus X (PVX) is the main pathogenicity determinant responsible for systemic necrosis in PVX-associated synergisms. J. Virol. 89, 2090–2103. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02896-14 (2015).

Szittya, G. et al. Low temperature inhibits RNA silencing-mediated defence by the control of siRNA generation. EMBO J. 22, 633–640. https://doi.org/10.1093/emboj/cdg74 (2003).

Zhang, X., Zhang, X., Singh, J., Li, D. & Qu, F. Temperature-dependent survival of Turnip crinkle virus-infected arabidopsis plants relies on an RNA silencing-based defense that requires dcl2, AGO2, and HEN1. J. Virol. 86, 6847–6854. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00497-12 (2012).

Leisner, S. M., Turgeon, R. & Howell, S. H. Effects of host plant development and genetic determinants on the long-distance movement of cauliflower mosaic virus in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 5, 191–202 (1993).

Bergès, S. E. et al. Natural variation of Arabidopsis thaliana responses to Cauliflower mosaic virus infection upon water deficit. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008557 (2020).

Suntio, T. & Makinen, K. Abiotic stress responses promote Potato virus A infection in Nicotiana benthamiana. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13, 775–784. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1364-3703.2012.00786.x (2012).

Nancarrow, N. et al. The effect of elevated temperature on Barley yellow dwarf virus-PAV in wheat. Virus Res. 186, 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2013.12.023 (2014).

Matros, A. et al. Growth at elevated CO2 concentrations leads to modified profiles of secondary metabolites in tobacco cv. SamsunNN and to increased resistance against infection with potato virus Y. Plant Cell Environ. 29, 126–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01406.x (2006).

Trebicki, P. et al. Virus disease in wheat predicted to increase with a changing climate. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 3511–3519. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12941 (2015).

Nachappa, P., Culkin, C. T., Saya, P. M. 2nd., Han, J. & Nalam, V. J. Water stress modulates soybean aphid performance, feeding behavior, and virus transmission in Soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 552–567. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.00552 (2016).

Bragard, C. et al. Status and prospects of plant virus control through interference with vector transmission. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 51, 177–201. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102346 (2013).

Blanc, S., Uzest, M. & Drucker, M. New research horizons in vector-transmission of plant viruses. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14, 483–491 (2011).

Smyrnioudis, I. N., Harrington, R., Katis, N. I. & Clark, S. J. The effect of drought stress and temperature on spread of barley yellow dwarf virus (BYDV). Agric. For. Entomol. 2, 6 (2000).

Bosquee, E., Boullis, A., Bertaux, M., Francis, F. & Verheggen, F. J. Dispersion of Myzus persicae and transmission of Potato virus Y under elevated CO2 atmosphere. Entomol. Exp. Applic. 166, 6 (2017).

Dader, B., Fereres, A., Moreno, A. & Trebicki, P. Elevated CO2 impacts bell pepper growth with consequences to Myzus persicae life history, feeding behaviour and virus transmission ability. Sci. Rep. 6, 19120. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep19120 (2016).

van Munster, M. et al. Water deficit enhances the transmission of plant viruses by insect vectors. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174398 (2017).

Yvon, M., Vile, D., Brault, V., Blanc, S. & van Munster, M. Drought reduces transmission of Turnip yellows virus, an insect-vectored circulative virus. Virus Res. 241, 131–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2017.07.009 (2017).

Anderson, R. M. & May, R. M. Coevolution of hosts and parasites. Parasitology 85, 411–426 (1982).

Ewald, P. W. Host–parasite relations, vectors, and the evolution of disease severity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 14, 465–485 (1983).

Froissart, R., Doumayrou, J., Vuillaume, F., Alizon, S. & Michalakis, Y. The virulence-transmission trade-off in vector-borne plant viruses: A review of (non-)existing studies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 365, 1907–1918. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0068 (2010).

Doumayrou, J., Avellan, A., Froissart, R. & Michalakis, Y. An experimental test of the transmission-virulence trade-off hypothesis in a plant virus. Evolution 67, 477–486 (2013).

Escriu, F., Perry, K. L. & Garcia-Arenal, F. Transmissibility of cucumber mosaic virus by Aphis gossypii correlates with viral accumulation and is affected by the presence of its satellite RNA. Phytopathology 90, 1068–1072 (2000).

Poulicard, N., Pinel-Galzi, A., Hebrard, E. & Fargette, D. Why Rice yellow mottle virus, a rapidly evolving RNA plant virus, is not efficient at breaking rymv1-2 resistance. Mol. Plant Pathol. 11, 145–154 (2010).

Rodriguez-Cerezo, E., Elena, S. F., Moya, A. & Garcia-Arenal, F. High genetic stability in natural populations of the plant RNA virus Tobacco Mild Green Mosaic virus. J. Mol. Evol. 32, 328–332 (1991).

Alizon, S., Hurford, A., Mideo, N. & Van Baalen, M. Virulence evolution and the trade-off hypothesis: History, current state of affairs and the future. J. Evol. Biol. 22, 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01658.x (2009).

Pagan, I. et al. Arabidopsis thaliana as a model for the study of plant-virus co-evolution. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 365, 1983–1995. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0062 (2010).

Granier, C. et al. PHENOPSIS, an automated platform for reproducible phenotyping of plant responses to soil water deficit in Arabidopsis thaliana permitted the identification of an accession with low sensitivity to soil water deficit. New Phytol. 169, 623–635. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01609.x (2006).

Alonso-Blanco, C. et al. 1,135 Genomes reveal the global pattern of polymorphism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell 166, 481–491 (2016).

Castilla, A. R. et al. Ecological, genetic and evolutionary drivers of regional genetic differentiation in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Evol. Biol. 20, 71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-020-01635-2 (2020).

Vasseur, F. et al. Adaptive diversification of growth allometry in the plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115(13), 3416–3421. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1709141115 (2018).

Vasseur, F. et al. Climate as a driver of adaptive variations in ecological strategies in Arabidopsis thaliana. Ann. Bot. 122(6), 935–945. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcy165 (2018).

Sartori, K. et al. Leaf economics and slow-fast adaptation across the geographic range of Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci. Rep. 9, 0758. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46878-2 (2019).

Brachi, B. et al. Investigation of the geographical scale of adaptive phenological variation and its underlying genetics in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Ecol. 22, 4222–4240. https://doi.org/10.1111/Mec.12396 (2013).

Frachon, L. et al. A genomic map of climate adaptation in Arabidopsis thaliana at a micro-geographic scale. Front. Plant Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.00967 (2018).

Zhang, S. et al. Antagonism between phytohormone signalling underlies the variation in disease susceptibility of tomato plants under elevated CO2. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 1951–1963. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/eru538 (2015).

van Munster, M. Impact of abiotic stresses on plant virus transmission by aphids. Viruses https://doi.org/10.3390/v12020216 (2020).

Normand, R. A. & Pirone, T. P. Differential transmission of strains of cucumber mosaic virus by aphids. Virology 36, 538–544 (1968).

Gutiérrez, S., Michalakis, Y., van Munster, M. & Blanc, S. Plant feeding by insect vectors can affect life cycle, population genetics and evolution of plant viruses. Funct. Ecol. 27, 13 (2013).

Martiniere, A. et al. A virus responds instantly to the presence of the vector on the host and forms transmission morphs. Elife 2, e00183 (2013).

Drucker, M. & Then, C. Transmission activation in non-circulative virus transmission: A general concept?. Curr. Opin. Virol. 15, 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2015.08.006 (2015).

Roossinck, M. J., Martin, D. P. & Roumagnac, P. Plant virus metagenomics: Advances in virus discovery. Phytopathology 105, 716–727. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-12-14-0356-RVW (2015).

Delseny, M. & Hull, R. Isolation and characterization of faithful and altered clones of the genomes of cauliflower mosaic virus isolates Cabb B-JI, CM4-184, and Bari I. Plasmid 9, 31–41 (1983).

Ebert, D. & Bull, J. J. Challenging the trade-off model for the evolution of virulence: Is virulence management feasible?. Trends Microbiol. 11, 15–20 (2003).

Fabre, J. et al. PHENOPSIS DB: An information system for Arabidopsis thaliana phenotypic data in an environmental context. BMC Plant Biol. 11, 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-11-77 (2011).

Hull, R. & Shepherd, R. J. The coat proteins of cauliflower mosaic virus. Virology 70, 217–220 (1976).

Doumayrou, J., Leblaye, S., Froissart, R. & Michalakis, Y. Reduction of leaf area and symptom severity as proxies of disease-induced plant mortality: The example of the Cauliflower mosaic virus infecting two Brassicaceae hosts. Virus Res. 176, 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2013.05.008 (2013).

Edwards, K., Johnstone, C. & Thompson, C. A simple and rapid method for the preparation of plant genomic DNA for PCR analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 1349 (1991).

Ruijter, J. M. et al. Amplification efficiency: Linking baseline and bias in the analysis of quantitative PCR data. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, e45 (2009).

Team, R. C. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/. (2017).

Kloke, J. D. & McKean, J. W. Rfit: Rank-based estimation for linear models. The R Journal 4, 57–64 (2012).

Harrell, F. E. J. et al. Hmisc: Harrell Miscellaneous. R package version 4.4–1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=Hmisc. (2020).

Marwick, B. & Krishnamoorthy, K. cvequality: Tests for the Equality of Coefficients of Variation from Multiple Groups. R software package version 0.1.3. (2019).

Venables, W. N. & Ripley, B. D. Modern Applied Statistics with S 4th edn. (Springer, New York, 2002) (ISBN 0-387-95457-0).

Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. WorldClim 2: New 1km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol. 37(12), 4302–4315 (2017).

Vidigal, D. S. et al. Altitudinal and climatic associations of seed dormancy and flowering traits evidence adaptation of annual life cycle timing in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Env. 39, 1737–1748. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.12734 (2016).

Méndez-Vigo, B. et al. Altitudinal and climatic adaptation is mediated by flowering traits and FRI, FLC, and PHYC genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 157(4), 1942–1955. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.111.183426 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank Alexis Bédiée, Rémy Dussaut and Léa Durand for technical support and image analyses. We are grateful to Rebecca Schwab, Detlef Weigel (Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tuebingen, Germany) and François Vasseur (CEFE, CNRS, Montpellier, France) for providing seeds of A. thaliana accessions. We are grateful to Helen Rothnie for critical reading and editing of the manuscript. This research was funded by the European Union and the Region Languedoc-Roussillon “Chercheur d’Avenir” (FEDER FSE IEJ 2014-2020; Grant Project “APSEVIR” #2015005464).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.E.B., M.v.M. and D.V. conceptualized the study. S.E.B., M.Y., D.M. and M.D. performed the experiments. S.E.B., M.v.M. and D.V. analyzed the data and wrote the original draft. All coauthors edited and reviewed the final version of the paper. All coauthors have agreed both to be personally accountable for his own contribution and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work is appropriately resolved.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bergès, S.E., Vile, D., Yvon, M. et al. Water deficit changes the relationships between epidemiological traits of Cauliflower mosaic virus across diverse Arabidopsis thaliana accessions. Sci Rep 11, 24103 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03462-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03462-x

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.