Abstract

NG2-glia, also referred to as oligodendrocyte precursor cells or polydendrocytes, represent a large pool of proliferative neural cells in the adult brain that lie outside of the two major adult neurogenic niches. Although their roles are not fully understood, we previously reported significant clonal expansion of adult NG2-cells from embryonic pallial progenitors using the StarTrack lineage-tracing tool. To define the contribution of early postnatal progenitors to the specific NG2-glia lineage, we used NG2-StarTrack. A temporal clonal analysis of single postnatal progenitor cells revealed the production of different glial cell types in distinct areas of the dorsal cortex but not neurons. Moreover, the dispersion and size of the different NG2 derived clonal cell clusters increased with age. Indeed, clonally-related NG2-glia were located throughout the corpus callosum and the deeper layers of the cortex. In summary, our data reveal that postnatally derived NG2-glia are proliferative cells that give rise to NG2-cells and astrocytes but not neurons. These progenitors undergo clonal cell expansion and dispersion throughout the adult dorsal cortex in a manner that was related to aging and cell identity, adding new information about the ontogeny of these cells. Thus, identification of clonally-related cells from specific progenitors is important to reveal the NG2-glia heterogeneity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

NG2-cells or NG2-glia, also known as oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs), represent a rapidly responding reservoir of new oligodendrocytes1,2,3. These cells express both the neuron-glia antigen 2 (NG2) chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan and the alpha receptor for platelet-derived growth factor (PDGFRα), as well as the oligodendrocyte marker, Olig2 (oligodendrocyte transcription factor 2). NG2-glia have been attributed different names over the years. Here, the terms NG2-glia or NG2-cells are used to define the glial cells expressing NG2, Olig2 and PDGFRα, in order to distinguish them from non-glial cells that also express NG24,5. In addition to oligodendrocytes, NG2-glia have the potential to generate a variety of cell types in vitro and in vivo, like astrocytes and neurons, both at postnatal or adult stages4,6,7,8. While the adult differentiation of these cells remains unclear9,10,11, several studies have focused on the capacity of NG2-glia to reprogramme into neurons in vivo12,13, opening the window to develop new therapeutic strategies involving this cell type.

NG2-glia come into close contact with other glial cells and neurons14, and they can receive direct synaptic inputs from neurons15, adjusting their behavior in response to neuronal activity. Furthermore, these cells are subject to the effects of a huge pool of transcription factors, neurotrophins, growth factors, metalloprotease inhibitors, cell adhesion and extracellular matrix, morphogens and immunomodulatory factors16. Transcriptome analysis has identified differences in mRNA content between NG2-glia and oligodendrocytes, suggesting the existence of two individual glial cell populations17. This molecular diversity reflects the potential heterogeneity of the NG2-glia population based on either their location or on the developmental factors that could affect their activity6. In addition, there is significant heterogeneity among NG2-glia in terms of proliferation, differentiation and cell cycle rates3,18,19. However, it seems that the proliferative activity of NG2-glia is independent of their role in myelination, suggesting that this pool of cells may have other roles.

Like stem cells, NG2-glia can divide asymmetrically, preventing the exhaustion of NG2-cells in the adulthood11,20. In this respect, we previously reported significant clonal expansion of NG2-cells from SVZ pallial embryonic progenitors between P120 and P24021. Here, to specifically target the cell progeny derived from postnatal NG2-progenitors at the single cell level, we used the new StarTrack clonal analysis strategy, NG2-StarTrack8. Previously, NG2-EGFP-StarTrack was used to target the progeny of NG2-cells at several time points. Specifically targeting NG2-progenitors at embryonic and postnatal stages demonstrated their heterogeneous potential. Indeed, these progenitors can produce different neural cell types in the pallial cortex in vivo, depending on the embryonic or postnatal stage targeted. Here, we performed a clonal analysis to target individual postnatal progenitors (P0) with these piggyBac plasmids and we analyzed the cell progeny of these progenitors at different adult stages (P90, P240 and P365). Clonal analyses revealed that the labeled sibling cells produced larger clusters of NG2-cells in older animals, situated in the white matter (WM), and in both the grey matter (GM) and WM. Although a small percentage of clonally-related cells were identified as astrocytes, there was no clear clonal relationship between astrocytes and NG2-cells. Together, our results reveal new information regarding the fate potential of postnatal progenitors in relation to NG2-glia heterogeneity, as well as the clonal relationship of NG2-cell progeny in different pallial areas with age.

Results

StarTrack clonal analysis to decipher the progeny of postnatal NG2-progenitors

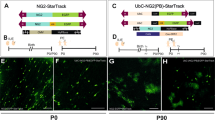

The StarTrack approach22 is based on 12 piggyBac plasmids that encode up to 6 different fluorophores (with either a nuclear or cytoplasmic localization), each driven by the GFAP-promoter, which are transfected along with a piggyBac transposase plasmid (hyPBase). This method allows single progenitor cells and their cell progeny to be targeted by piggyBac-driven stochastic integration into the genome. This strategy was modified to target the NG2 lineage in vivo by using novel plasmids carrying the mouse NG2-promoter (mNG2), referred to as NG2-StarTrack (Fig. 1A 22). Here, the mixture of NG2-StarTrack plasmids and the hyPBase transposase was injected into the lateral ventricles (LVs) of mice, which were electroporated at P0-P1 (Figs. 1B, S1). At P90, P240 and P365 we then performed a clonal analysis to assess the age-related changes in the postnatal NG2 derived cell progeny and in the progenitor cell potential.

Clonal NG2-StarTrack approach. (A) Scheme of the twelve NG2-StarTrack piggyBac vectors along with the CMV-HyPBase transposase. The NG2-StarTrack contains inverted terminal repeats (IR) that the transposase recognizes, allowing it to randomly integrate copies of the NG2-StarTrack plasmids into the genome. (B) The consequences of postnatal electroporation at P0 were analyzed at different adult ages (P90, P240 and P365). (C) Targeted pallial pNSC produced different fluorescent cells in the cortex with immature morphologies, close to the LVs, as well as cells with different neural morphologies. White insets define the amplified images: (D) clonal related cells in the corpus callosum; (E) Small group of sibling cells in the GM; (F) Larger group of sibling cells in the GM. (G) Diagram of clonal analysis. Targeting single NSCs generates an inheritable and stable label in their progeny, creating a color and a barcode. The barcode is formed by a serial number (1–6) taking into account the presence or absence of XFPs and their location (cytoplasmic and nuclear). The labelled cells are widespread throughout the cerebral cortex along the rostro-caudal axis: PE postnatal electroporation, CC corpus callosum, NSC neural stem cell, XFPs different fluorescent proteins. Slice 50 µm. Scale bar 100 µm and 50 µm.

NG2-StarTrack labelled cells in the dorsal cortex formed either big clusters, small groups or remained as individual cells (Fig. 1C). Different morphologies could be distinguished in WM (Fig. 1D) and GM (Fig. 1E,F), although the labeled immature cells located close to the ventricle were not considered in these clonal analyses. The cell progeny of targeted NG2-progenitors displayed an inheritable and stable color code at the single-cell level (Figs. 1G and S1). The different fluorescent reporter proteins were detected in separate channels to define the presence/absence of each fluorophore: 1, YFP; 2, mKO; 3, mCerulean; 4, mCherry; 5, mTSapphire; 6, EGFP (Fig. S1B). Each channel was assigned an emission color, except for mT-Sapphire that was represented as dark blue and far red in grey color. Accordingly, the cellular barcode allows the clonally-related cells to be rapidly recognized based on the presence (represented as 1–6) or absence (0) of the fluorescent proteins and their location, whereby the first number corresponds to cytoplasmic labeling and the second number to its nuclear location (Figs. 1G and S1C). Hence, the theoretical color-code created for each clonal cluster can produce more than 14,000 combinations23. Sequential sections along the rostro-caudal axis were used to analyze both the location and spatial dispersion of the sibling cells. The frequency of the different color-code combinations was also estimated to rule out the clones that appeared more frequently (data not shown).

Characterization of the adult NG2 derived progeny of early postnatal progenitor cells

NG2-StarTrack can target single progenitor cells with an active NG2 promoter and their derived cell progeny, identified using different neural markers at distinct adult ages (Fig. 2). The cell’s morphology and immunolabeling indicated the identity of the sibling cells, and among the 9 animals used in the clonal analysis (3 animals at each age) the proportion of NG2-cells was around 97% of the total cells analyzed (4496 of total cell analyzed) (Fig. 2B). This proportion was higher than that of the sibling astrocytes analyzed at all ages, which represented just 3% of the total cells (Fig. 2B). Similarly, the dispersion of these clonal astrocytes along the rostro-caudal axis was more restricted than that of the NG2 sibling clusters (Fig. 2B).

Cell derived progeny of targeted postnatal progenitor cells. (A) Scheme of the NG2-StarTrack approach. P0 pups were electroporated and analyzed at adult stages (P90; P240; P365). (B) NG2-cells represent 97% of the clonally related cells (4368 cells) and protoplasmic astrocytes just 3% (128 cells) in the total of 12 animals analyzed. The dispersion of total NG2-cells along the rostro-caudal axis was greater than that of astrocytes. Also, the dispersion of sibling NG2-cells relative to astrocytes showed significant differences. (C–J) Co-localization of neural markers with NG2-StarTrack labeled cells in the adult cerebral cortex (P90). (C, D) Astrocytes co-localize with GFAP and S100β. (E, F) Cluster of NG2-cells in the grey and white matter were identified with Olig2. (G, H) PDGFRα marked NG2- cells. (I–F) APC identified some immature oligodendrocytes: NG2-cells in red, astrocytes in green. Statistically significant differences are indicated by asterisks: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. The line in the bars indicates the mean of data. Slices 50 µm. Scale bar: 20 µm.

Although, the morphology of the labelled cells might be sufficient to identify the different types of glial cells, except for those with only nuclear labeling, we performed immunohistochemistry to assess the distribution of different glial markers. Labelled astrocytes were identified through the expression of both glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP: Fig. 2C) and S100 calcium binding protein beta (S100β: Fig. 2D). Cells in the NG2 lineage co-localized with labelling for Olig2 (Fig. 2E,F) and PDGFRα (Fig. 2G,H). The expression of NG2 is downregulated in oligodendrocytes, and some immature oligodendrocytes were labelled by these antibodies and identified by their expression of adenomatous polyposis Coli (APC/CC1: Fig. 2I–J). These cells did not express neuronal markers. After their characterization, the different groups of cells were classified in function of their cortical location, either in the GM, WM or both, revealing the identity of the progeny of dorsal postnatal progenitors after NG2-StarTrack targeting. The clonally-related cells in the GM and WM were mainly identified as NG2-cells, although some labelled astrocytes were detected in the GM. There were differences among the clusters of glial cells in terms of the number of cells and their dispersion along rostro-caudal axis.

Clonal analysis of adult derived NG2-cell progeny after NG2-StarTrack targeting of individual postnatal progenitors

We then analyzed the clonal cell pattern of the pallial glial cells derived from postnatal (P0) progenitors with an active NG2 promoter (Fig. 3A) at different adult ages (P90, P240 and P365). We randomly selected 66 NG2-cell clones from three different animals of each age (P90:18, P240:30 and P365:18), attending to their color code and frequency. Their rostro-caudal location was calculated from the rostral end of the LV as the initial point of electroporation, and their dispersion was defined by the position of all the sibling cells at the different levels along the rostro-caudal axis. There was an increase in the number of cells per NG2 clone with age (Fig. 3C) and therefore, there was greater cell dispersion of most sibling NG2-cells (Fig. 3B), forming larger clones (Fig. 3C) with age (Fig. 3D). While the clones at P90 dispersed across 50–200 microns, in older animals the clones were larger and had a more heterogeneous dispersion. Hence, the biggest NG2 clone contained 607 cells at P240 (8 months) and the smallest just 2 cells (Fig. 3D). In addition, sibling NG2-cells were located in the GM, WM or both as mentioned above (Fig. 3E–I). At P240, the clones located in the WM and GM had more cells and a greater dispersion than at other ages (Fig. 3H,I). Nonetheless, the sibling cells located in the GM alone had fewer cells (Fig. 3E,G,I) and less cell dispersion than those in the WM. In addition, the presence of regionally mixed clones formed by NG2-cells located in both the GM and WM was notable, occupying the deeper cortical layers and the corpus callosum (Fig. 3F). Those clones located in both cortical areas constituted 62% of total labelled NG2-cells (Fig. 3G) displaying a huge cell dispersion, between 200 and 650 microns, at P240 and P365 (Fig. 3H). In this regard, the biggest clonal clusters were located in the WM (P240) or in both the WM and GM at the different ages analyzed (Fig. 3I). Together, the clonally-related NG2-cells formed larger clones in older animals, with an increase in cell dispersion. Moreover, some clonal cells were located in both the corpus callosum and the deeper layers of the dorsal cortex. These mixed clones were identified at all ages and they had more cells per clone.

Clonal analysis and distribution of NG2-cells. (A) Diagram of the PE and NG2-StarTrack vectors. The tissue was analyzed from P90 onwards and clonal related cell progeny were located in dorsal areas of the brain. (B) The dispersion of the sibling NG2-cells increased with age. (C) The number of cells per clone was higher with age. (D) Clonal relationship of dispersion and the size of sibling cells at P90, P240 and P365. The dots show the different clonally related cells at each age and was normalized to the total number of cells per clone. (F) NG2-StarTrack labeled sibling cells in the corpus callosum and deeper layers of the cerebral cortex. The different channels show the presence/absence of the fluorescent protein and their locations (cytoplasmic or nuclear). Circles represent the color code of the clonal cells. (G) Proportion of sibling NG2-cells located in the GM, WM or both. (H) The dispersion of those clones was heterogeneous, from 150 to 650 μm depending on the clone size (fewer cells per clone was correlated with less dispersion along the rostro-caudal axis) A total of 10 clones were located in both areas (P90:3, P240:5 and P365:2). (I) Floating bars of clonal related NG2-cells in the GM, WM and both at the different time points. The larger clusters of sibling cells are located in both tissues at P90 and P365. The dark line in the bars and scatter dot-plot represents the mean. The data was represented as the mean ± SEM and the dots represented the different clones (B, C, E). P90 data is represented in blue, P240 in green and P365 in red. The GM is in soft grey, the WM in grey and Both are in dark grey. PE postnatal electroporation, CC corpus callosum, GM Grey matter, WM white matter; Both, grey and white matter; XFPs, different fluorescent proteins: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Slices 50 µm. Scale bar: 50 µm.

Clonal analysis of adult derived-astroglial progeny following NG2-StarTrack targeting of single postnatal progenitors

After targeting pallial progenitor cells at P0, we designed a temporal clonal analysis (Fig. 4) to analyze the astrocytes labelled with the NG2-StarTrack at adult stages (P90, P240 and P365: Figs. 4A and 5A). From individual tagged postnatal NG2-progenitors we randomly selected 4368 adult labelled cells, from which 128 were identified as astrocytes in 40 clones located in the GM (P90:13; P240:15; P365:12). The number of fibrous astrocytes per clone was very low, usually just per one cell and thus, they were not considered in the clonal analysis. The cells were characterized based on both their morphology and marker expression (Figs. 4B and S1D,E). The astroglial clones displayed significant fewer cells per clone than the NG2 clones (Fig. 4B,C) and at P90, 8% of the labelled cells were astrocytes and 92% corresponded to NG2-glia. By contrast, astrocytes made up 2% of the tagged cells at P240 and P365. Comparing between ages, the number of protoplasmic astrocytes per clone at P90 was significantly different in older animals (Fig. 4D), with a maximum of 15 cells per clone at P240. Some labelled astrocytes with no sibling cells were observed at different ages (P90:3; P240:1; P365:3) and although yet they were not considered in the final clonal analysis, they could provide information about the behavior of early postnatal progenitors. In addition, the dispersion of astrocytes was apparently similar at all the ages selected (Fig. 4E,F). The majority of clonally-related astrocytes dispersed from 50 to 200 microns along the rostro-caudal axis (Fig. 4F), while the clonal size varied from 2 to 15 cells (Fig. 4D,F). Indeed, in relationship to the size of the clones, astrocytes exhibited homogeneous proliferation with age, in contrast to the NG2-glia clones in which the number of sibling cells increased in older animals (Fig. 5B). Comparing the cell distribution over the electroporated area (Fig. 5C), labelled astrocytes were preferentially located caudally to the NG2 labelled cells, which was most evident at P240 and P365 (Fig. 5C). Nevertheless, the distribution of these glial cells along the rostro-caudal axis was not significantly different (Fig. 5D). In summary, astroglial NG2-derived cell clones had a smaller dispersion and there were fewer cells per clone at the different ages analyzed, reflecting a homogeneous behavior of the tagged postnatal progenitor cells that contrasted with that of the progenitors that gave rise NG2-cells.

Clonal analysis and distribution of protoplasmic astrocytes. (A) Scheme of the postnatal electroporation and data analysis from P90 onwards. Diagram of the NG2-StarTrack mixture used to perform the clonal analysis. (B) Confocal imaging displayed two astrocytes surrounding by big group of sibling NG2-cells. (C) There were fewer of astrocytes than NG2-cells analyzed. (D) The number of clonal astrocytes increased at P240 but not at P365. (E) The dispersion of cells was constant with ageing. (F) Relationship of clonal dispersion and size of clonally-related astrocytes at P90, P240 and P365. The dots indicate the different clonal related cells per age and their size was normalized according to the number of sibling cells. The dispersion along the rostro-caudal axis was from 50 to 200 microns. The dark line in the bars and scatter dot-plot represents the mean, and the data was represented as mean ± SEM. The dots represent the different clones: P90 data is in blue, P240 in green and P365 in red. The dark line represents the mean in the dot plot graphs (C, D, E): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. PE postnatal electroporation, XFPs different fluorescent proteins. Slices 50 µm. Scale bar: 50 µm.

Summary of the temporal clonal analysis of NG2-derived cell progeny and their dispersion throughout the rostro-caudal axis. (A) Diagram of the NG2-StarTrack mixture and representation of the location of sibling cells in the adult brain. (B) Representative graph of the number of cells per clone with age, taking into account their cell identity. There are more NG2-cells with age whereas the number of astrocytes remains constant with age. (C) Dispersion of NG2 derived cell progeny along the rostro-caudal axis. Labeled cells were located between 500 to 4000 microns (starting from the beginning of the LVs). Astrocytes appeared caudally with respect NG2-cells at all ages but the dispersion pattern was similar (D). Astrocytes are in green and NG2-cells in red: PE postnatal electroporation, XFPs different fluorescent proteins, LV lateral ventricle.

To conclude, we reveal that clones of NG2-cells in the cortical GM and WM show the largest cell dispersion at the different ages. In addition, we showed a lack of regional mixing of the clones of NG2-cells. These results witness the heterogeneity in both the postnatal NG2-progenitors and their cell progeny.

Discussion

This study is a NG2-StarTrack clonal analysis of the adult cell progeny derived from individual NG2 pallial progenitors at early postnatal ages. To tag NG2- progenitor cells, we used the genomic multicolor genetic tracing tool, NG2-StarTrack, designed to track the cell progeny of individual postnatal progenitors from the SVZ in vivo8. Our data revealed the presence of clones of either NG2-glia or astrocytes with different spatio-temporal extensions. However, in contrast to embryonic NG2-progenitors7,8,24, no neuronal cells were derived from postnatal progenitors in cortical areas. Previous lineage analysis of neural cells reported the capability of progenitor cells to generate both astrocyte and oligodendrocyte cells in vitro25,26,27,28 and in vivo29.

NG2-cell clones were widespread throughout the cortical rostro-caudal axis, either in the WM and GM. In addition, a subpopulation of astroglial cells were tagged with the NG2-StarTrack mixture. These clones had a constant number of cells over time, unlike the NG2-cell clones that increased in number and dispersion. We also reveal the existence of regional mixed clones formed by clonally-related NG2-cells in both the cortical GM and WM. These mixed clones had more cells and a greater dispersion in the temporal analysis, arguing the NG2-cell heterogeneity may not only be related to their fate but also, to their location and to ontogenic processes6,11. Regional heterogeneity of NG2-cells has been reported, based on different properties like cell cycle length30,31, proliferative response18 and differentiation rates32. Even, NG2-cells in the same area present differences in terms of their transcription factor expression or that of the GPR17, G-protein couple receptor (GPCR33). In the adult brain, our lineage-tracing analyses of NG2-postnatal precursors revealed they proliferated distinctly and displayed different cell fate patterns across adulthood. As reported for the adult progeny of embryonic progenitors, the number of clonally-related cortical NG2-cells increases notably with age21. Nevertheless, some of those clones were in both the GM and WM, in contrast to embryonic progenitors. These postnatal progenitors proliferate and differentiate into NG2-cells, producing larger clones at older ages, and showing greater heterogeneity in terms of both cell dispersion and clonal size. This clonal expansion could be related to their proliferative activity over the animal’s lifetime and beyond the neurogenic niches1,34,35. Otherwise, other studies using Cre-lox mice reported that the proliferative rate of NG2-cells decreased with age3,4,5. As previously suggested using a different StarTrack approach21, it is possible that those pallial-derived NG2 clones increase their size at the expense of the direct differentiation in oligodendrocytes of ventral derived NG2 clones. Thus, those differences can be explained as a heterogeneous pool of progenitor cells with different proliferative properties throughout age and domain. Further, previous data reported that the mitotic status of adult NG2-cells is unrelated to their developmental origin3. However, there is a coexistence of both slow-cycling stem cell‐like NG2-cells with more rapidly cycling amplifying cells3,20,30, promoting that the cell cycle of NG2-cells varies in relation to the brain areas and age. Moreover, a smart approach on lineage-targeted transcriptomics reveals the role of transcription factors in lineage transition of glial cells in both physiologic and pathological conditions36. At this respect, complementary genetic approaches might assess new insights related to their NG2-cells heterogeneity and fate potential.

Our data show that postnatal progenitor cells gave rise to only glial lineages in cortical areas, while embryonic NG2-progenitors produce both neuronal and glial cell lineages8. In this regard, time-lapse imaging37 and in vivo StarTrack tracing38 revealed the impact of progenitor location on fate potential. Furthermore, it has been proposed that NG2-glia can differentiate into neurons under specific conditions and locations39. In this respect, several in vitro and in vivo approaches have been used to decipher the multipotent potential of progenitor cells and their capacity to generate different neural cell types40,41. Cre-inducible mouse lines produced few astrocytes after induction19, but in other transgenic mice, no astrocytes or neurons were found at adult stages42. All these differences suggest the need to focus on progenitor heterogeneity8,43,44 which is essential to address the cell fate of neural cells.

NG2-glia generate astrocytes during development7,44,45, although it remains unclear if that capacity persists in adults39,46,47. The small subpopulation of astroglial cells in relation the number of NG2-cells, derived from NG2 postnatal progenitors, revealed that these cells have different proliferation rates related not only to age but also, to their origin. Clonal astrocytes were less abundant than NG2-cells at all stages and their cell dispersion in the rostro-caudal axis was homogeneous. Thus, as well NG2-glia, astrocytes are characterized by their heterogeneity at different levels, including ontogeny22,48, morphology49,50, cortical GM and WM location22,51, transcriptomic signatures52,53 or response to brain lesions54,55. In addition, astrocytes could influence NG2-glia behavior during development, an interaction that may have an important influence on gliogenesis, ageing and even injury56. Recently, sibling astrocytes were shown to preferentially establish GAP-junction coupling relative to the unrelated astrocytes57. This coupled response between sibling cells may be implicated in physiological and pathological events both, astrocytes and NG2-glia55,58. All these data reinforce the strong heterogeneity of these neural cells at a morphological, functional and genetic level, opening the window to develop new lineage tracing approaches not only based on multicolor labeling but also, on stable genome editing59. New transcriptome tools could shed light on the pathologies mechanisms and further therapies60.

Ageing is related to the loss of myelin, which is in turn correlated with the loss of cognitive and motor skills, which could be a consequence of the generation of fewer oligodendrocytes61. However, NG2-cells preserve the ability to divide in adulthood62,63 and moreover, NG2-glia respond early to brain insults (like astrocytes), migrating towards to the injury site and increasing their rate of proliferation19,25. Several reports indicate that most NG2-cells in the cortical GM could be part of a different population of NG2-cells under physiological conditions24, although their functions are not fully understood. Thus, NG2-cells increase in number with age, which may be useful to design new therapies to combat cell aging related phenomena. Their capability to generate neurons is not yet fully understood, yet their stem cell like characteristics or their possible reprogramming could be relevant to neurodegenerative diseases and ageing12,13,64.

In conclusion, beyond their role in myelination, NG2-glia represent a significant pool of glial cells with diverse functionalities, as well as unique properties that contribute to CNS homeostasis and development. The importance of their origin, cell fate and heterogeneity is still unclear. Thus, further clonal analysis complemented with genetic cell identity strategies might help gain new insights into their behavior, heterogeneity and fate potential.

Materials and methods

Animals

All mice were maintained under standard housing conditions at the animal facility of the Cajal Institute. All procedures involving animals were carried out in accordance with the European Union guidelines on the use and welfare of experimental animals (2010/63/EU) and those of the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture (RD 1201/2005 and L 32/2007). All the experiments were approved by the CSIC Bioethical Committee (PROEX 223/16). Both male and female of C57/BL6 mice were used indistinctly as we have not observed any difference associated with sex in the biological processes studied. The day of birth was considered as postnatal day 0 (P0) and in all the experiments, a minimum of n = 3 animals was studied for each condition.

Vectors

NG2-StarTrack constructs were designed as described previously8. Briefly, the GFAP-StarTrack constructs were used to generate the different NG2 piggyBac vectors with the six different reporter proteins and H2B histone sequence to drive the tag into the nucleus. The human GFAP promoter was removed and replaced with a murine NG2 promoter65. The hyperactive transposase of the PiggyBac system (CMV-hyPBase) was kindly provided by Dr Bradley and all the plasmids used were sequenced to confirm successful cloning (Sigma–Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). For all injections, the plasmid mixtures contained the twelve NG2-StarTrack constructs and a hyperactive transposase of the PiggyBac system under the CMV promoter to integrate copies of the NG2-StarTrack plasmids randomly into postnatal progenitor cells.

Postnatal electroporation

Postnatal electroporation was performed as described previously38. Briefly, a plasmid solution containing the plasmid mixture (1–2 µg/µl) and 0.1% Fast Green was injected into the LVs of perinatal animals on day P0-1 using a glass micropipette. After plasmid injection, all pups were electroporated with electrode paddles, placing electroconductive LEM Gel (DRV1800, MORETTI S.P.A.) on both paddles to avoid damage to the pups and to achieve successful current flow. We administered five pulses of 100 V, each pulse lasting 50 ms and separated by 950 ms intervals. The positive electrode was positioned on top of the dorsal cortex to direct the negatively charged DNA. After the five pulses, the electroporated animals were reanimated for several minutes on a 37 °C heating plate before returning them to the mother’s nest. The mice were analyzed from P30 onwards (at least three animals per experimental group).

Histological and immunohistological procedures

The adult animals were anesthetized with pentohbarbital (Dolethal, 40–50 mg/Kg) and when fully anesthetized, they were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), and their brain was removed and placed overnight in small tubes with 4% PFA in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB). Serial vibratome brain section (50 µm thick) were mounted onto glass slides with Mowiol and stained for different neural markers. Slices were permeabilized with phosphate buffer saline containing Triton X-100 (PBS-T) and then incubated for at least 30 min in blocking solution (5% normal goat serum-NGS- in PBS-T 0.1%). The sections were then incubated O/N at 4 °C with the following antibodies markers: rabbit polyclonal anti-Olig2 (Millipore-AB9610); rabbit polyclonal anti-GFAP (Dako-31745); mouse monoclonal anti-APC (Calbiochem (OP80); rabbit polyclonal anti-PDGFRα (Cell Signalling-3169); a mouse monoclonal anti-S100β (Abcam-Ab66028). After at least three washes with buffer, the sections were incubated for up to 2 h with Alexa far red goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse IgG (1:1.000, Alexa Fluor 633 or 647, Molecular Probes). Finally, the sections were washed several times with buffer, mounted on slides, coverslipped and observed in an epifluorescence microscope (Eclipse E600; Nikon, USA).

Imaging acquisition

The sections were examined under an epifluorescence microscope equipped with GFP (FF01-473/10), mCherry (FF01-590/20) and Cy5 (FF01-628/40-25) filters. Images were then acquired on a TCS-SP5 confocal microscope (Leica, TCS-SP5). The confocal laser lines were maximal around 40% in all samples and the conditions for each laser was constant for each animal. The different reporter proteins were taken in separate channels controlling the overlapping between them. The wavelength of excitation (Ex) and emission (Em) was (in nanometers): mT-Sapphire (Ex: 405; Em: 520–535), mCerulean (Ex: 458; Em:468–480), EGFP (Ex:488; Em: 498–510), YFP (Ex:514; Em: 525–535), mKO (Ex: 514; Em: 560–580), mCherry (Ex: 561; Em: 601–620), and Alexa Fluor 633/647 (Ex: 633; Em: 650–760). Maximum projection images were analyzed using LASX software (Leica) and Fiji software ImageJ. All stitching and contrast adjustments were performed with the LasX software (LasX Industries) and Photoshop CS5 software (Adobe). The rostro-caudal axis was reconstructed using the Traken2 plug-in for ImageJ and was estimated as the distance between the beginning of the LVs and the last slice containing cells of that clone. Moreover, the clonal dispersion was calculated considering the distance between the first and last slice containing clonally related cells.

Data analysis

For each experiment, the sections were analyzed serially and the cells were counted using the manual cell counter plug-in of ImageJ software. Afterwards, the proportion of those cells in the pallial areas was calculated. For statistics, GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad, USA) was used and the statistical significance between two groups was assessed with two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests, using ANOVA for multiple comparisons between the groups. The values were represented as mean ± SEM along the experimental data. A confidence interval of 95% (p < 0.05) was determined for the statistically significant values. Critical values of *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 were adopted to determine statistical differences. Graphs were obtained using Excel Office, GraphPad Prism 6.0 (San Diego, USA) and CorelDRAW Graphic Suite 2018 (Corel Corporation, Ottawa, Canada).

Clonal analysis was performed on numbered cells and examined through the presence/absence of fluorophore and their location. A barcode was created as a binary signature (0 = absence, 1 = presence of cytoplasmic and nuclear marker of YFP, mKO, mCerulean mCherry, mTSapphire and EGFP) in all the animals analyzed. Since cell labeling and intensity in the maximal projection depend on the z-position of the cells, that could not be constant in relation to the intensity of the different reporter proteins, we followed specific criteria to avoid misleading. When the labelled cell does not exhibit a clear label of the cell nucleus, we just considered that this corresponds to a cytoplasmic labeling. On the other hand, when there is a clear limit discriminating the nucleus and the cytoplasm, within the same fluorescent channel, we consider the labeling to be both nuclear and cytoplasmic. Finally, the cells sharing the same combination/location of fluorophores/signature were catalogued as clones after classifying all the labeled cells.

References

Nishiyama, A., Chang, A. & Trapp, B. D. NG2+ glial cells: a novel glial cell population in the adult brain. J. Neuropahtol. Exp. Neurol. 58, 1113–1124 (1999).

Boda, E. & Buffo, A. Beyond cell replacement: unresolved roles of NG2-expressing progenitors. Front. Neurosci. 8, 122. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2014.00122 (2014).

Psachoulia, K., Jamen, F., Young, K. M. & Richardson, W. D. Cell cycle dynamics of NG2 cells in the postnatal and ageing brain. Neuron Glia Biol. 5(3–4), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1740925X09990354 (2009).

Dimou, L. & Gallo, V. NG2-glia and their functions in the central nervous system. Glia 63, 1429–1451 (2015).

Nishiyama, A., Suzuki, R. & Zhu, X. NG2 cells (polydendrocytes) in brain physiology and repair. Front. Neurosci. 8, 1–7 (2014).

Trotter, J., Karram, K. & Nishiyama, A. NG2 cells: properties, progeny and origin. Brain Res. Rev. 63, 72–82 (2010).

Huang, W. et al. Novel NG2-CreERT2 knock-in mice demonstrate heterogeneous differentiation potential of NG2 glia during development. Glia 62, 896–913 (2014).

Sánchez-González, R., Bribián, A. & López-Mascaraque, L. Cell fate potential of NG2 progenitors. Sci. Rep. 10, 9876. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66753-9 (2020).

Kondo, T. & Raff, M. Oligodendrocyte precursor cells reprogrammed to become multipotential CNS atem cells. Sciences 8, 1754–1757 (2000).

Richardson, W. D., Young, K. M., Tripathi, R. B. & McKenzie, I. NG2-glia as multipotent neural stem cells: fact or fantasy?. Neuron 70(4), 661–673 (2011).

Nishiyama, A., Boshans, L., Goncalves, C. M., Wegrzyn, J. & Patel, K. D. Lineage, fate, and fate potential of NG2-glia. Brain Res. 1638(1), 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2015.08.013 (2016).

Pereira, M. et al. Direct reprogramming of resident NG2 glia into neurons with properties of fast-spiking parvalbumin-containing interneurons. Stem Cell Rep. 9(3), 742–751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.07.023 (2017).

Wang, L. L. & Zhang, C. L. Engineering new neurons vivo reprogramming in mammalian brain and spinal cord. Cell Tissue Res. 371, 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-017-2729-2 (2018).

Butt, A. M. et al. Synantocytes: new functions for novel NG2 expressing glia. J. Neurocytol. 31, 551–565. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025751900356 (2002).

Bergles, D. W., Jabs, R. & Steinhäuser, C. Neuron-glia synapses in the brain. Brain Res. Rev. 63(1–2), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.12.003 (2011).

Parolisi, R. & Boda, E. NG2 glia: novel roles beyond re-/myelination. Neuroglia 1, 151–175. https://doi.org/10.3390/neuroglia1010011 (2018).

Valny, M. et al. A single-cell analysis reveals multiple roles of oligodendroglial lineage cells during post-ischemic regeneration. Glia 66, 1068–1081 (2018).

Hill, R. A., Patel, K. D., Medved, J., Reiss, A. M. & Nishiyama, A. NG2 cells in white matter but not gray matter proliferate in response to PDGF. J. Neurosci. 33(36), 14558–14566 (2013).

Dimou, L. & Gotz, M. Glial cells as progenitors and stem cells: new roles in the healthy and diseased brain. Physiol. Rev. 94, 709–737 (2014).

Young, K. M. et al. Oligodendrocyte dynamics in the healthy adult CNS: evidence for myelin remodeling. Neuron 77, 873–885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2013.01.006 (2013).

García-Marqués, J., Núñez-Llaves, R. & López-Mascaraque, L. NG2-glia from pallial progenitors produce the largest clonal clusters of the brain: time frame of clonal generation in cortex and olfactory bulb. J. Neurosci. 34(6), 2305–2313 (2014).

García-Marqués, J. & López-Mascaraque, L. Clonal identity determines astrocyte cortical heterogeneity. Cereb. Cortex 23(6), 1463–1472. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhs134 (2013).

Figueres-Oñate, M., Garciá-Marqués, J. & López-Mascaraque, L. UbC-StarTrack, a clonal method to target the entire progeny of individual progenitors. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–13 (2016).

Rivers, L. E. et al. PDGFRA/NG2 glia generate myelinating oligodendrocytes and piriform projection neurons in adult mice. Nat. Neurosci. 11(12), 1392 (2008).

Carnow, T. B., Barbarese, E. & Carson, J. H. Diversification of glial lineages: a novel method to clone brain cells in vitro on nitrocellulose substratum. Glia 4(3), 256–268 (1991).

Lubetzki, C., Goujet-Zalc, C., Demerens, C., Danos, O. & Zalc, B. Clonal segregation of oligodendrocytes and astrocytes during in vitro differentiation of glial progenitor cells. Glia 6(4), 289–300 (1992).

Levison, S. W. & Goldman, J. E. Both oligodendrocytes and astrocytes develop from progenitors in the subventricular zone of postnatal rat forebrain. Neuron 10(2), 201–212 (1993).

Luskin, M. B. & McDermott, K. Divergent lineages for oligodendrocytes and astrocytes originating in the neonatal forebrain subventricular zone. Glia 11(3), 211–226 (1994).

Delaunay, D. et al. Early neuronal and glial fate restriction of embryonic neural stem cells. J. Neurosci. 28(10), 2551–2562. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5497-07.2008 (2008).

Simon, C., Götz, M. & Dimou, L. Progenitors in the adult cerebral cortex: cell cycle properties and regulation by physiological stimuli and injury. Glia 59, 869–881 (2011).

Clarke, L. E. et al. Properties and fate of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells in the corpus callosum, motor cortex, and piriform cortex of the mouse. J. Neurosci. 32, 8173–8185 (2012).

Kang, S. H., Fukaya, M., Yang, J. K., Rothstein, J. D. & Bergles, D. E. NG2+ CNS glial progenitors remain committed to the oligodendrocyte lineage in postnatal life and following neurodegeneration. Neuron 68, 668–681 (2010).

Viganò, F. et al. GPR17 expressing NG2-Glia: oligodendrocyte progenitors serving as a reserve pool after injury. Glia 64, 287–299 (2016).

Hughes, E. G., Kang, S. H., Fukaya, M. & Bergles, D. E. Oligodendrocyte progenitors balance growth with self-repulsion to achieve homeostasis in the adult brain. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 668–676 (2013).

Dimou, L., Simon, C., Kirchhoff, F., Takebayashi, H. & Go, M. Progeny of olig2-expressing progenitors in the gray and white matter of the adult mouse. Cereb. Cortex 28, 10434–10442 (2008).

Weng, Q. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics uncovers glial progenitor diversity and cell fate determinants during development and gliomagenesis. Cell Stem Cell 24(5), 707–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2019.03.006 (2019).

Ortega, F. et al. Oligodendrogliogenic and neurogenic adult subependymal zone neural stem cells constitute distinct lineages and exhibit differential responsiveness to Wnt signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 602–613 (2013).

Sánchez-González, R., Figueres-Oñate, M., Ojalvo-Sanz, A. C. & López-Mascaraque, L. Cell progeny in the olfactory bulb after targeting specific progenitors using different UbC-StarTrack approaches. Genes 11, 305. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11030305 (2020).

Du, X., Zhang, Z., Zhou, H. & Zhou, J. Differential modulators of NG2-glia differentiation into neurons and glia and their crosstalk. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 5, 2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10571-020-00843-0 (2020).

Figueres-Oñate, M. et al. Lineage tracing and clonal cell dynamics of postnatal progenitor cells in vivo. Stem Cell Reports. 13, 700–712 (2019).

Parmigiani, E. et al. Heterogeneity and bipotency of astroglial-like cerebellar progenitors along the interneuron and glial lineages. J. Neurosci. 35, 7388–7402 (2015).

Huang, W., Guo, Q., Bai, X., Scheller, A. & Kirchhoff, F. Early embryonic NG2 glia are exclusively gliogenic and do not generate neurons in the brain. Glia 67, 1094–1103 (2019).

Calzolari, F. et al. Fast clonal expansion and limited neural stem cell self-renewal in the adult subependymal zone. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 490–492 (2015).

Bergles, D. E. & Richardson, W. D. Oligodendrocyte development and plasticity. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 8, a020453 (2016).

Kirdajova, D. & Anderova, M. NG2 cells and their neurogenic potential. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 50, 53–60 (2019).

Guo, F., Ma, J., McCauley, E., Bannerman, P. & Pleasure, D. Early postnatal proteolipid promoter-expressing progenitors produce multilineage cells in vivo. J. Neurosci. 29(22), 7256–7270 (2009).

Tognatta, R. et al. Transient cnp expression by early progenitors causes Cre-Lox-based reporter lines to map profoundly different fates. Glia 65, 342–359 (2017).

Bayraktar, O. A., Fuentealba, L. C., Alvarez-Buylla, A. & Rowitch, D. H. Astrocyte development and heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7(1), 020362 (2014).

Matyash, V. & Kettenmann, H. Heterogeneity in astrocyte morphology and physiology. Brain Res. Rev. 63(1–2), 2–10 (2010).

Chai, H. et al. Neural circuit-specialized astrocytes: transcriptomic, proteomic, morphological, and functional evidence. Neuron 95(3), 531-549.e9 (2017).

Köhler, S., Winkler, U. & Hirrlinger, J. Heterogeneity of astrocytes in grey and white matter. Neurochem. Res. 5, 2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-019-02926-x (2019).

Bayraktar, O. A. et al. Astrocyte layers in the mammalian cerebral cortex revealed by a single-cell in situ transcriptomic map. Nat. Neurosci. 23(4), 500–509 (2020).

Batiuk, M. Y. et al. Identification of region-specific astrocyte subtypes at single cell resolution. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 1220 (2020).

Martín-López, E., García-Marques, J., Núñez-Llaves, R. & López-Mascaraque, L. Clonal astrocytic response to cortical injury. PLoS ONE 8, e74039. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0074039 (2013).

Bribián, A., Pérez-Cerda, F., Matute, C. & López-Mascaraque, L. Clonal glial response in a multiple sclerosis mouse model. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 23, 375 (2018).

Clemente, D., Ortega, M. C., Melero-Jerez, C. & de Castro, F. The effect of glia-glia interactions on oligodendrocyte precursor cell biology during development and in demyelinating diseases. Front. Cell Neurosci. 7, 268 (2013).

Gutiérrez, Y. et al. Sibling astrocytes share preferential coupling via gap junctions. Glia 67, 1852–1858 (2019).

Barriola, S., Pérez-Cerdá, F., Matute, C., Bribián, A. & López-Mascaraque, L. A clonal NG2-glia cell response in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Cells 9, 1279 (2020).

Kumamoto, T. et al. Direct readout of neural stem cell transgenesis with an integration-coupled gene expression switch. Neuron S0896–6273(20), 30407–30414 (2020).

Jäkel, S. & Williams, A. What have advances in transcriptomic technologies taught us about human white matter pathologies?. Front. Cell Neurosci. 14, 238 (2020).

Rivera, A., Vanzuli, I., Arellano, J. J. & Butt, A. Decreased regenerative capacity of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (NG2-glia) in the ageing brain: a vicious cycle of synaptic dysfunction, myelin loss and neuronal disruption?. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 13(4), 413–418 (2016).

Dawson, M. R. L., Polito, A., Levine, J. M. & Reynolds, R. NG2-expressing glial progenitor cells: an abundant and widespread population of cycling cells in the adult rat CNS. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 24, 476–488 (2003).

Lasiene, J., Matsui, A., Sawa, Y., Wong, F. & Horner, P. J. Age-related myelin dynamics revealed by increased oligodendrogenesis and short internodes. Aging Cell 8(2), 201–213 (2009).

Torper, O. et al. In vivo reprogramming of striatal NG2 glia into functional neurons that integrate into local host circuitry. Cell Rep. 12(3), 474–481 (2015).

Sellers, D. L., Maris, D. O. & Horner, P. J. Postinjury niches induce temporal shifts in progenitor fates to direct lesion repair after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 29, 6722–6733 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research Grants from the MICINN (PID2019-105218RB-I00), MINECO (BFU2016-75207-R) and the Fundación Ramón Areces (Ref. CIVP9A5928). We are very grateful to the Animal, Imaging and Microscopy Facilities of the Instituto Cajal. We are also thankful to Ana Bribian, Sonsoles Barriola, Ana Cristina Ojalvo Sanz and Ana Ciria, members of the lab for stimulating discussions and their help with the clonal analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.L-M conceived, designed and supervised the research and approved the final manuscript. R.S.-G. performed experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the paper. N.S. participated in confocal microscopy and clonal analyses.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sánchez-González, R., Salvador, N. & López-Mascaraque, L. Unraveling the adult cell progeny of early postnatal progenitor cells. Sci Rep 10, 19058 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75973-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75973-y

This article is cited by

-

Adult neurogenesis and aging mechanisms: a collection of insights

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Multicolor strategies for investigating clonal expansion and tissue plasticity

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.