Abstract

Tocopherols, lipid-soluble antioxidants play a crucial role in the antioxidant defense system in higher plants. The antioxidant function of α-tocopherol has been widely studied; however, experimental data on the formation of its oxidation products is missing. In this study, we attempt to provide spectroscopic evidence on the detection of oxidation products of α-tocopherol formed by its interaction with singlet oxygen and lipid peroxyl radical. Singlet oxygen was formed using photosensitizer rose bengal and thylakoid membranes isolated from Arabidopsis thaliana. Singlet oxygen reacts with polyunsaturated fatty acid forming lipid hydroperoxide which is oxidized by ferric iron to lipid peroxyl radical. The addition of singlet oxygen to double bond carbon on the chromanol head of α-tocopherol forms α-tocopherol hydroperoxide detected using fluorescent probe swallow-tailed perylene derivative. The decomposition of α-tocopherol hydroperoxide forms α-tocopherol quinone. The hydrogen abstraction from α-tocopherol by lipid peroxyl radical forms α-tocopheroxyl radical detected by electron paramagnetic resonance. Quantification of lipid and protein hydroperoxide from the wild type and tocopherol deficient (vte1) mutant Arabidopsis leaves using a colorimetric ferrous oxidation-xylenol orange assay reveals that α-tocopherol prevents formation of both lipid and protein hydroperoxides at high light. Identification of oxidation products of α-tocopherol might contribute to a better understanding of the protective role of α-tocopherol in the prevention of oxidative damage in higher plants at high light.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Higher plants convert solar energy into chemical energy in light-driven photosynthetic reactions. The light reactions involve the capture of solar energy by chlorophylls and the splitting of water into protons, electrons and molecular oxygen. The simultaneous occurrence of molecular oxygen with excited chlorophylls is potentially harmful to plants as singlet oxygen (1O2) might be formed by excitation energy transfer from triplet chlorophyll to molecular oxygen1,2,3,4,5. Singlet oxygen addition to the double bond forms lipid hydroperoxide (LOOH) by the ene reaction, whereas the cycloaddition of 1O2 across the double bond forms endoperoxides. In the presence of oxidized transition metals (e.g. Fe3+), LOOH is oxidized to lipid peroxyl radical (LOO•). As the latter possess unpaired electron on oxygen atom, it has capability to abstract a hydrogen atom from other adjacent polyunsaturated fatty acid and thus initiates propagation of lipid peroxidation. To prevent lipid peroxidation, higher plants evolved numerous protection mechanisms comprising non-enzymatic and enzymatic antioxidant defense system. In non-enzymatic reactions, a variety of lipophilic antioxidants can either prevent the initiation or cause the termination of lipid peroxidation. Among lipophilic antioxidants, tocochromanols (tocopherols, tocotrienols and plastochromanol-8) and isoprenoid quinones (plastoquinone-9 and plastoquinol-9) play a crucial role in the prevention of lipid peroxidation6,7,8. It was shown that α-tocopherol (α-TOH) prevents lipid peroxidation in both non-radical and radical reactions. In non-radical reactions, α-TOH maintains physical and chemical quenching of 1O29,10. In the physical quenching, electron transfer from α-TOH to 1O2 forms singlet exciplex, which undergoes to triplet exciplex by intersystem crossing11,12. In the chemical quenching, the oxidation of α-TOH by 1O2 leads to the formation of α-tocopherol hydroperoxide (α-TOOH) which decomposes to more stable α-tocopherol-quinone (α-TQ)13,14. Whereas the formation of α-TQ was shown in the model systems15,16, isolated chloroplasts17 and leaves14,18, no evidence on α-TOOH formation has been provided. In the radical reaction, α-TOH scavenges LOO• . The hydrogen abstraction from α-TOH by LOO• leads to the formation of α-tocopheroxyl radical (α-TO•) which might be re-reduced by ascorbate to α-TOH while monodehydroascorbate radical (Asc•−) is formed19,20,21. The α-TO• was detected in the model systems22,23; however, no evidence on the formation of α-TO• has been provided in thylakoid membranes.

In this study, we provided for the first-time experimental evidence on the formation of α-TOOH and α-TO• in the thylakoid membranes isolated from Arabidopsis plant. We showed that (1) oxidation of α-TOH by 1O2 forms α-TOOH monitored by fluorescence spectroscopy and (2) oxidation of α-TOH by LOO• is associated with the appearance of α-TO• detected by electron paramagnetic resonance.

Materials and methods

Plant material, growth conditions and stress treatments

In the present work, Arabidopsis thaliana, WT (Columbia-0) and tocopherol cyclase deficient mutant, vte1 (lacking tocopherols and plastochromanol-8) were used24. Plants were grown using commercially available substrate (Potgrond H, Klasmann- Deilmann Substrate, Germany) in a growing chamber (Photon Systems Instruments, Drásov, Czech Republic) under precise conditions: photoperiod of 8 h light/16 h dark (120 µmol photons m−2 s−1), temperature of 22 °C and humidity 60%. High light stress was accomplished in AlgaeTron AG 230 (Photon Systems Instruments, Drásov 470, Czech Republic) by illuminating 5–6 weeks old plants to white light (1500 μmol photons m−2 s−1) for 13 h at a temperature of 8 °C.

Thylakoid membrane preparation

Thylakoid membranes were isolated from high light exposed plants using the protocol developed by Casazza et al.25. Harvesting of rosette leaves (0.3–0.5 g) from plants was done followed by floating them on ice-cold water for 10–20 min in the dark and then blotted. Leaves were rapidly homogenized in 10–20 ml of grinding buffer comprising EGTA (5 mM), EDTA (5 mM), MgCl2 (5 mM), NaHCO3 (10 mM), sorbitol (0.4 M) and tricine/NaOH (20 mM, pH 8.4) and 0.5% (w/v) fatty acid-free BSA was added just before the grinding. Homogenized suspension was filtered through 2 layers of cheesecloth by applying a gentle hand pressure to increase the final thylakoid yield. The filtrate was centrifuged at 2600 g for 3 min at 4 °C, followed by re-suspending the pellet in 10–20 ml of resuspension buffer containing EDTA (2.5 mM), HEPES (20 mM, pH 7.6) MgCl2 (5 mM), NaHCO3 (10 mM), sorbitol (0.3 M) and 0.5% (w/v) fatty acid-free BSA. Centrifugation was done at 2600 g for 3 min at 4 °C and the pellet was washed again in re-suspension buffer without adding fatty acid-free BSA and then resuspended in 10–20 ml of hypotonic buffer containing EDTA (2.5 mM), MgCl2 (5 mM), NaHCO3 (10 mM), HEPES (20 mM, pH 7.6) and 0.5% (w/v) fatty acid-free BSA. Thylakoid membranes were collected by centrifugation at 2600 g for 3 min at 4 °C. Finally, the pellet was suspended in a small volume (0.5–1 ml) of resuspension buffer and was stored at -80 °C in the dark until use. The chlorophyll concentrations from thylakoid preparations were calculated from the absorbance at 645 and 663 nm of 80% (v/v) acetone extract, according to Arnon26.

Determination of α-tocopherol and α-tocopherol quinone by HPLC

The amount of α-TOH and α-TQ was assessed by the reverse-phase HPLC analysis using postcolumn reduction with platinum following the protocol described in Nowicka and Kruk27. To avoid the auto-oxidation of α-TOH and α-TQ standard, we stored standard at -80 °C in several concentrations. To avoid the auto-oxidation of α-TOH and α-TQ extracted from leaves, we performed the liquid extraction of α-TOH and α-TQ in chilled methanol. We considered the pre-analytical methods mentioned in Giusepponi et al.28. α-TOH (30 µM) in the presence of rose bengal (5 µM ) and from thylakoid membranes (750 µg Chl ml−1) was extracted in methanol by vortexing (5 min) and centrifuged at 2000 g for 60 s at 4 °C, the supernatant was transferred to HPLC vial using a syringe with needle. Minimum of three independent biological replicates were measured to enable an assessment of significance. Isocratic analysis (0.8 ml min−1 at 25 °C) was done using methanol as mobile phase and a LiChrospher 100 RP-18 column (5 µm) LiChroCART 250-4 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Alliance e 2695 HPLC System (Waters Corporation, Milford MA, USA) equipped with a 2998 Photodiode Array (PDA) and a 2475 Fluorescence (FLR) detectors were used. Operation and data processing was performed by Empower 3 Chromatography Data Software (Waters Corporation, Milford MA, USA) (https://www.waters.com/waters/en_US/Empower-3-Chromatography-Data-Software). For determination of α-TOH, fluorescence detection was used (λex = 290 nm, λem = 330 nm). To quantify α-TOH and α-TQ, the calibration curve established in our lab by plotting the peak area at the wavelength for various concentrations of standards was used. α-TOH and α-TQ standards were obtained from Sigma Aldrich GmbH (Germany).

Determination of α-tocopherol hydroperoxide by fluorescence spectroscopy

The formation of α-TOOH and organic hydroperoxides (ROOH) was measured with a fluorescence spectrophotometer (FP-8000 Series Fluorometer, Easton, MD 21601, USA) using a fluorescent probe swallow-tailed perylene derivative (SPY-LHP) (Dojindo Molecular Technologies Inc. Rockville, MD, USA) 29,30. Rose bengal (5 µM) with α-TOH (20 μM) (for α-TOOH detection) and thylakoid membranes (20 µg ml−1) (for ROOH detection) were illuminated in the presence of SPY-LHP (2.5 µM) with green and red light (1000 μmol photons m−2 s−1) for 5 and 15 min, respectively. Green and red light was obtained by a halogen lamp with a light guide (Schott KL 1500, Schott AG, Mainz, Germany) using band-pass interference filter (560 FS10-25) and a long-pass edge interference filter (λ > 600 nm) (Andover Corporation, Salem, NH, USA), respectively. Illumination by green and red light was used to excite rose bengal and chlorophylls and simultaneously avoid SPY-LHP photosensitization. After red light exposure, hydroperoxides were extracted from thylakoid membranes into absolute ethanol and SPY-LHPox fluorescence was measured. SPY-LHPox fluorescence was measured in three biologically distinct samples. The fluorescence emission spectrum was measured at a spectral range between 500 and 650 nm (excitation wavelength, 488 nm). The spectral slit-width for excitation and emission monochromators was 5 nm. The fluorescence intensity at 538 nm was used for the quantification of α-TOOH and ROOH formation.

Singlet oxygen and radical detection by EPR spectroscopy

The formation of 1O2, LOO• , α-TO• and Asc•− in the rose bengal system and 1O2, organic peroxyl radical (ROO•), α-TO• and Asc•− in the thylakoid membranes was measured with EPR spectrometer MiniScope MS400 (Magnettech GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Formation of 1O2 was detected using hydrophilic probe TMPD (2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidone) purchased from Sigma Aldrich GmbH (Germany). The 1O2 mediated oxidation of diamagnetic TMPD produces paramagnetic 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidone-1-oxyl (TEMPONE) which gives EPR signal detected by EPR spectroscopy. Illumination of rose bengal (5 μM) and thylakoid membranes (250 μg Chl ml−1) was done in the presence of 25 mM TMPD and 40 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) at room temperature. Formation of LOO• and ROO• was detected indirectly by DMPO-OL and DMPO-OR adduct EPR signals, respectively using a hydrophilic spin trap DMPO (5,5-dimethyl-pyrroline-1-oxide) purchased from (Sigma Aldrich GmbH, Germany). Illumination of rose bengal (50 μM) with linolenic acid (250 mM) and thylakoid membranes (250 μg Chl ml−1) was done in the presence of 50 mM DMPO, 10 mM Fe3+ and 40 mM MES-NaOH (pH 6.5). Formation of α-TO• and Asc•− was measured in presence of exogenous α-TOH (50 mM) and sodium ascorbate (50 mM). Illumination of thylakoid membranes was done with white light (1000 µmol m−2 s−1) using a halogen lamp with a light guide (Schott KL 1500, Schott AG, Mainz, Germany) for the fixed periods and the spectra were recorded. A minimum of three independent biological replicates were measured to assess the significance of measurements. EPR settings were as follows: microwave power, 10 mW; modulation amplitude, 1 G; modulation frequency, 100 kHz; sweep width, 100 G; scan rate, 1.62 G s−1.

Quantification of lipid and protein hydroperoxides by absorption spectroscopy

To determine LOOH and protein hydroperoxides (POOH) concentration in high light illuminated leaves, lipid and protein extraction was done by following the method of Grintzalis31. Leaves harvested from high light illuminated plants were weighed, approximately equal fresh weight of leaves was homogenized in 2–5 ml of 10 mM inorganic phosphate buffer containing 0.5 mM butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), homogenate was centrifuged at 20,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C and then the filtrate was vigorously vortexed with 2–5 ml of chloroform (CHCl3): methanol (CH3OH) (2:1) for the lipid extraction. After vigorous vortex, 100% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (volume of 100% TCA should be 10% of phosphate buffer used for homogenization) was added. The mixture was vortexed for 30–60 s and incubated in ice-cold water for 20 min followed by centrifugation at 20,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. After centrifugation, three separate layers (top aqueous layer, middle protein disc and the lower layer containing lipids) were visible. Lower lipid layer was collected in a fresh Eppendorf tube, dried under the nitrogen stream and used for FOX assay. Protein discs were washed with 10% TCA using ultrasonic homogenizer, homogenized protein discs were centrifuged at 20,000g for 10 min at 4 °C and the pellet was dissolved in urea (8 M) and used for FOX assay. FOX assay was performed in three biological replicates to confirm the significance of measurements. FOX reagent was prepared fresh by dissolving 15.2 mg xylenol orange (XO) (final concentration 2 mM) in 5 ml of 0.5 M H2SO4 and bringing to final 10 ml with distilled H2O, 5 mM H2SO4 was prepared by diluting the stock H2SO4 with distilled H2O, 8 mM Fe2+ reagent was prepared by dissolving 31.2 mg ferrous ammonium sulfate in 10 ml of 5 mM H2SO4. All reagents were prepared fresh before use. Lower lipid layer collected in a fresh Eppendorf tube was dried under the nitrogen stream. The dried lipid was dissolved in absolute methanol and protein pellet dissolved in 8 M urea was mixed with Fe2+ and FOX reagent and incubated for 30 min at 30 °C. LOOH and POOH formation was monitored by following the changes in absorbance at 560 nm using UV–Visible Spectrophotometer (UV-510 Thermo Spectronic Unicam, UK).

Results

Consumption of α-tocopherol detected by HPLC

To monitor the consumption of α-TOH by its oxidation during 1O2 quenching and LOO• scavenging, the amount of α-TOH was determined by the reverse-phase HPLC analysis using a fluorescence detector. Figure 1 shows the chromatograms of α-TOH added to rose bengal (Fig. 1A) and α-TOH extracted from thylakoid membranes (Fig. 1B). Under the chromatographic conditions used in this study, the observed chromatograms show the peak corresponding to α-TOH at retention time 12.7 min in both rose bengal (Fig. 1A, dark trace) and thylakoid membranes (Fig. 1B, dark trace). When rose bengal and thylakoid membranes were illuminated, suppression of the peak at retention time 12.7 min was observed (Fig. 1A and B, light trace). The concentration of α-TOH in rose bengal (Fig. 1C) and thylakoid membranes (Fig. 1D) in dark was 6.12 ± 0.18 nmol ml−1 and 0.55 ± 0.00 nmol ml−1, where it decreases to 0.63 ± 0.19 nmol ml−1 and 0.06 ± 0.03 nmol ml−1 in light, respectively. Rose bengal-photosensitized 1O2 formation caused complete consumption of α-TOH due to 1O2 quenching, whereas α-TOH consumption in thylakoid membranes was due to 1O2 quenching and LOO• scavenging.

α-Tocopherol and α-tocopherol quinone detection in rose bengal (A, C, E) and thylakoid membranes isolated from WT Arabidopsis (B, D, F) by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). In A, chromatograms of α-TOH (30 µM) in methanol with rose bengal (5 µM) measured in dark and after white light illumination. In B, chromatograms of α-TOH extracted in methanol from dark and white light illuminated WT thylakoid membranes (750 µg Chl ml−1). Rose bengal and thylakoid membranes were illuminated with white light (1000 µmol photons m−2 s−1) for 5 min and 15 min, respectively. In C-D, quantification of the α-TOH consumption in rose bengal and thylakoid membranes determined as area under a peak at retention time 12.7 min. In E-F, quantification of α-TQ in rose bengal and thylakoid membranes determined as area under a peak at retention time 9.1 min. Each data point represents the mean ± SD of biological replicates (n = 3).

Singlet oxygen quenching by α-tocopherol monitored by EPR spectroscopy

Singlet oxygen quenching by α-TOH was studied by EPR spectroscopy using TMPD as a spin probe. Oxidation of diamagnetic TMPD by 1O2 forms paramagnetic TEMPONE detected by EPR spectroscopy. Singlet oxygen was generated either by photosensitization of rose bengal or illumination of thylakoid membranes isolated from Arabidopsis. Addition of TMPD spin probe to rose bengal or thylakoid membranes in the dark did not result in the appearance of TEMPONE EPR spectra (Fig. 2A and B, control trace and Fig. 2C and D, control bar), whereas photosensitization of rose bengal or illumination of thylakoid membranes resulted in the formation of TEMPONE EPR signal (Fig. 2A and B, 1O2 trace and Fig. 2C and D, 1O2 bar). When photosensitization of rose bengal or illumination of thylakoid membranes was performed in the presence of α-TOH, TEMPONE EPR signal was significantly suppressed (Fig. 2A and B, 1O2 + α-TOH trace and Fig. 2C and D, 1O2 + α-TOH bar). These observations indicate that α-TOH serves as an efficient quencher of 1O2 generated from the photosensitization of rose bengal or illumination of Arabidopsis thylakoid membranes.

Singlet oxygen formation in rose bengal (A, C) and thylakoid membranes isolated from WT Arabidopsis (B, D) monitored by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy using the spin probe TMPD. In A-B, TEMPONE EPR spectra were recorded in the control and illuminated rose bengal (5 µM) or thylakoid membranes (250 µg Chl ml−1) in the presence of TMPD (25 mM) and phosphate buffer (40 mM, pH 7.0). Illumination of rose bengal and thylakoid membranes was performed with white light (1000 µmol photons m−2 s−1) for 5 min and 15 min, respectively. When TEMPONE EPR spectrum was measured in the presence of α-TOH (1 mM), 0.05% Triton-X 100 was used to prevent precipitation of α-TOH. In C-D, quantification of 1O2 generated by photosensitization of rose bengal and illumination of thylakoid membranes determined from the height of the central peak of the first derivative of the EPR absorption spectra. Each data point represents the mean ± SD of biological replicates (n = 3).

Formation of α-tocopherol hydroperoxide detected by fluorescence spectroscopy

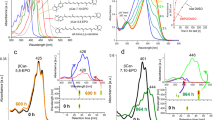

To monitor the formation of α-TOOH after oxidation of α-TOH by 1O2, fluorescent probe swallow-tailed perylene derivative (SPY-LHP) was used. In this reaction, the oxidation of non-fluorescent SPY-LHP by α-TOOH forms fluorescent oxidized derivative (SPY-LHPox) which provides fluorescence in the green region of the spectrum. Fluorescence spectrum of SPY-LHPox shows fluorescence maximum at 538 nm and 575 nm (Fig. 3A, lower dashed trace) as previously shown by Soh et al.30. When SPY-LHPox fluorescence spectrum was measured in the presence of rose bengal and α-TOH in dark, no change was seen in fluorescence at 538 nm whereas, fluorescence at 575 nm was increased due to fluorescence of rose bengal (Fig. 3A, control trace). Rose bengal-photosensitized 1O2 formation caused a significant enhancement in SPY-LHPox fluorescence at 538 nm due to α-TOOH formation (Fig. 3A, α-TOOH trace and Fig. 3C, α-TOOH bar). It cannot be excluded that the formation of rose bengal hydroperoxide contributes to the enhancement in SPY-LHPox fluorescence. To confirm that α-TOOH is reduced to α-TOH by ascorbate, the effect of sodium ascorbate on α-TOOH formation was studied. When sodium ascorbate was added to α-TOOH formed by the photosensitized oxidation of α-TOH, the SPY-LHPox fluorescence was decreased (Fig. 3A, α-TOOH + Asc trace and Fig. 3C, α-TOOH + Asc bar). These observations reveal that oxidation of α-TOH by 1O2 forms α-TOOH which is reduced back to α-TOH by ascorbate. When SPY-LHPox fluorescence spectrum was measured in the thylakoid membranes in dark, SPY-LHPox fluorescence was low due to fluorescence of only SPY-LHP (Fig. 3B, control trace and Fig. 3D, control bar). When thylakoid membranes were illuminated in the presence of SPY-LHP, increase in the SPY-LHPox fluorescence was observed (Fig. 3B, ROOH trace and Fig. 3D, ROOH bar). As thylakoid membranes are abundant in lipid and protein, SPY-LHPox fluorescence may be due to the formation of organic hydroperoxides comprising LOOH and POOH. The addition of sodium ascorbate to thylakoid membranes caused a decrease in SPY-LHPox fluorescence (Fig. 3B, ROOH + Asc trace and Fig. 3D, ROOH + Asc bar) confirming that α-TOOH is reduced to α-TOH by ascorbate and thus it prevents the formation of ROOH. These results indicate that α-TOH prevents oxidation of lipids and proteins by 1O2 quenching. It is proposed here that detection of α-TOOH from thylakoid membranes might be feasible after separation of α-TOOH from other organic hydroperoxides (LOOH, POOH) and identification by 1H-NMR and mass spectrometry32.

α-Tocopherol hydroperoxide formation in rose bengal (A, C) and organic hydroperoxide formation in thylakoid membranes isolated from WT Arabidopsis (B, D) monitored by SPY-LHPox fluorescence spectroscopy. In A, SPY-LHPox fluorescence spectra were achieved by the illumination of rose bengal (5 µM) with green light obtained using band-pass interference filter (λ = 560 nm, HBW = 10 nm). In B, SPY-LHPox fluorescence spectra were obtained by the illumination of thylakoid membranes (20 µg Chl ml−1) with red light using a long-pass edge interference filter (λ > 600 nm). In C, Quantification of the α-TOOH generated by photosensitization of rose bengal and the effect of sodium ascorbate. In D, Quantification of the ROOH generated by photosensitization of chlorophyll and the effect of α-TOH regeneration by sodium ascorbate. Illumination of rose bengal and thylakoid membranes with SPY-LHP (2.5 µM) was done with green and red light (1000 µmol photons m−2 s−1) for 5 min and 15 min in the absence or presence of α-TOH (20 µM) and sodium ascorbate (500 µM), respectively. The SPY-LHPox fluorescence intensity at 538 nm was used to quantify the rose bengal-photosensitized formation of α-TOOH and chlorophyll photosensitized formation of ROOH. Each data point represents the mean ± SD of biological replicates (n = 3).

Formation of α-tocopherol quinone detected by HPLC

To study the formation of α-TQ by decomposition of α-TOOH, the amount of α-TQ was determined by the reverse-phase HPLC analysis using postcolumn reduction with platinum. Figure 1A and B shows the observed chromatograms with the peak corresponding to α-TQ at retention time 9.1 min. Whereas almost no peak at retention time 9.1 min was detected in rose bengal in dark (Fig. 1A, dark trace), a distinguishable peak was observed in thylakoid membranes (Fig. 1B, dark trace). When rose bengal with α-TOH, and thylakoid membranes were illuminated, peak at retention time 9.1 min was enhanced (Fig. 1A and B, light trace). The concentration of α-TQ in rose bengal (Fig. 1E) and thylakoid membranes (Fig. 1F) in dark was 0.05 ± 0.01 nmol ml−1 and 0.39 nmol ml−1, where it increases to 3.3 ± 0.04 nmol ml−1 and 0.59 ± 0.07 nmol ml−1 in light, respectively. These results indicate that α-TOOH decomposes to α-TQ.

Formation of α-tocopheroxyl radical by EPR spectroscopy

To detect the formation of LOO• by decomposition of LOOH in the rose bengal and linolenic acid samples (Fig. 4A) and formation of ROO• by decomposition of ROOH in thylakoid membranes isolated from white light WT Arabidopsis (Fig. 4B), EPR spin-trapping technique was employed using DMPO as the spin-trap compound. Addition of DMPO spin trap to rose bengal and linolenic acid samples or thylakoid membranes in the dark did not result in the appearance of DMPO-OL/DMPO-OR adduct EPR signal (Fig. 4A and B, control trace and Fig. 4C and D, control bar). When rose bengal and linolenic acid samples were illuminated in the presence of Fe3+, lipid alkoxyl radical (LO•) (DMPO-OL) adduct EPR signal was detected (Fig. 4A, LOO• trace and Fig. 4C, LOO• bar). When thylakoid membranes were illuminated, organic alkoxyl radical (RO•) (DMPO-OR) adduct EPR signal was detected (Fig. 4B, ROO• trace and Fig. 4D, ROO• bar). The observation that DMPO-OL adduct EPR signal in the rose bengal and linolenic acid samples was insensitive to SOD excluded contribution of hydroxyl radical (DMPO-OH) adduct (Fig. 4A, LOO• + SOD trace and Fig. 4C, LOO• + SOD bar). In the thylakoid membranes, SOD lowered EPR signal to half (Fig. 4B, ROO• + SOD trace and Fig. 4D, ROO• + SOD bar) revealing that DMPO-OH adduct contributes to overall EPR signal. The addition of α-TOH to the rose bengal and linolenic acid samples or thylakoid membranes caused complete suppression of the formation of LOO•/ROO• (Fig. 4A and B, LOO•/ROO• + α-TOH trace and Fig. 4C and D, LOO•/ROO• + α-TOH bar), while α-TO• was formed (Fig. 4A and B, α-TO• trace and Fig. 4C and D, α-TO• bar). When sodium ascorbate was added together with the α-TOH, α-TO• formed by the oxidation of α-TOH by LOO•/ROO• was disappeared and Asc•− appeared (Fig. 4A and B, Asc•− trace and Fig. 4C and D, Asc•− bar). These observations reveal that the oxidation of α-TOH by LOO•/ROO• forms α-TO•, which is reduced back to α-TOH by ascorbate forming Asc•−. These results show that (1) α-TOH scavenges LOO•/ROO• in the thylakoid membranes, (2) α-TO• is formed by the oxidation of α-TOH by LOO•/ROO• and (3) α-TO• is reduced to α-TOH by sodium ascorbate while ascorbate is oxidized to Asc•−.

Formation of peroxyl, α-tocopheroxyl and monodehydroascorbate radicals in rose bengal and linolenic acid samples (A, C) and in thylakoid membranes (B, D) monitored by EPR spectroscopy. In A, DMPO-OL adduct EPR spectrum in control (control trace), DMPO-OL adduct EPR spectrum after 5 min of white light illumination (LOO• trace), effect of SOD on DMPO-OL adduct EPR spectrum (LOO• + SOD trace), effect of α-TOH on DMPO-OL adduct EPR spectrum (LOO• + α-TOH trace), α-TO• spectrum (α-TO• trace) and Asc•− spectrum (Asc•− trace) were recorded in rose bengal and linolenic acid samples. In B, DMPO-OR adduct EPR spectrum in control (control trace), DMPO-OR adduct EPR spectrum after 5 min of white light illumination (ROO• trace), effect of SOD on DMPO-OR adduct EPR spectrum (ROO• + SOD trace), effect of α-TOH on DMPO-OR adduct EPR spectrum (ROO• + α-TOH trace), α-TO• spectrum (α-TO• trace) and Asc•− spectrum (Asc•− trace) were recorded in thylakoid membranes. When EPR spectra were measured in the presence of α-TOH, 0.05% Triton-X 100 was used to prevent precipitation of α-TOH. In C, quantification of the LOO• generated by decomposition of LOOH, effect of SOD on LOO• and effect of α-TOH on LOO•, α-TO• generated by oxidation of α-TOH during scavenging of LOO• and Asc•− formed during the regeneration of α-TOH from α-TO•. In D, quantification of the ROO• generated by decomposition of ROOH effect of SOD on ROO• and effect of α-TOH on ROO•, α-TO• generated by oxidation of α-TOH during scavenging of ROO• and Asc•− formed during the regeneration of α-TOH from α-TO•. Linolenic acid (250 mM) in the presence of rose bengal (50 µM) or thylakoid membranes (250 µg Chl ml−1) were illuminated with white light (1000 µmol photons m−2 s−1) for 5 min. DMPO-OL/DMPO-OR EPR spectra were measured in the presence of DMPO (50 mM), α-TOH (50 mM), Fe3+ (10 mM), SOD (200 U ml−1), sodium ascorbate (50 mM) and phosphate buffer (40 mM, pH 7.6). Each data point represents the mean ± SD of biological replicates (n = 3).

Formation of lipid hydroperoxide (A) and protein hydroperoxide (B) in WT and vte1 Arabidopsis quantified by colorimetric ferrous oxidation-xylenol orange (FOX) assay. The concentration of LOOH and POOH was established from the calibration curve obtained using hydrogen peroxide. Each data point represents the mean ± SD of biological replicates (n = 3). A significant difference between high light-exposed WT and vte1 Arabidopsis plant is indicated by the asterisk ** (Student’s test p < 0.001).

Formation of lipid and protein hydroperoxides by absorption spectroscopy

As SPY-LHP reacts with several types of organic hydroperoxides (LOOH, POOH, α-TOOH), LOOH and POOH were isolated from WT and vte1 Arabidopsis leaves and quantified using a colorimetric ferrous oxidation-xylenol orange (FOX) assay. In this assay, Fe3+ formed by the oxidation of Fe2+ by ROOH interacts with xylenol orange (XO) in acidic environments forming an XO–Fe complex with the maximum absorption at 560 nm. The concentration of LOOH (Fig. 5A) and POOH (Fig. 5B) formed in high light illuminated WT and vte1 Arabidopsis leaves were in the range of several tens of nanomoles. Relatively higher LOOH formation in vte1 suggests that α-TOH prevents LOOH formation in Arabidopsis leaves at high light.

Discussion

The antioxidant mechanism of α-TOH was previously examined in many studies14,33,34,35. In the current study, we have shown that consumption of α-TOH caused either by photosensitization of rose bengal (Fig. 1A) or illumination of thylakoid membranes (Fig. 1B) is associated with formation of α-TOH oxidation products: (1) oxidation of α-TOH by 1O2 forms α-TOOH and (2) oxidation of α-TOH by LOO• forms α-TO•. When other antioxidants are present such as ascorbate, oxidation products of α-TOH (α-TOOH and α-TO•) are recycled back to α-TOH. Since ascorbate is present in a higher amount than α-TOH, it forms a large reservoir of antioxidant, which could effectively maintain α-TOH restoration. As the most important structural feature of α-TOH in antioxidant activity is chromanol head, oxidation reactions underlying the interaction of 1O2 and LOO• with electron-rich double bonds in chromanol head are discussed below.

Oxidation of α-tocopherol by singlet oxygen forms α-tocopherol hydroperoxide

It was formerly shown that the methylene blue-photosensitized oxidation of α-TOH results in the formation of α-TOOH in model systems36,37. Detection of α-TOOH using fluorescent probe SPY-LHP showed that 1O2 photosensitized by rose bengal caused significant formation of α-TOOH (Fig. 3A). It was previously proposed that reaction of α-TOH with 1O2 occurs via ene reaction36. In agreement with this, we propose here that oxidation of α-TOH by 1O2 occurs by the addition of 1O2 to double bond carbon on the chromanol head. Chromanol head of α-TOH contains three electron-rich double bonds at the 4th, 6th and 8th positions on the phenol ring which make it a suitable substrate for the ene addition of 1O2. In the chemical quenching of 1O2 by α-TOH, the interaction of 1O2 with electron-rich double bonds at the 8th position of the chromanol head forms α-TOOH by ene reaction.

It was formerly shown that α-TOOH formed by the methylene blue-photosensitized oxidation of α-TOH is reduced to α-TOH by ascorbate37. Our results of α-TOOH formed by the rose bengal photosensitized oxidation of α-TOH and its reduction to α-TOH by ascorbate (Fig. 3A and C) agrees with the previous reports. Interestingly, the observation that α-TOOH was not fully reduced to α-TOH reveals that α-TOOH decomposes to α-TQ.

Oxidation of α-tocopherol by lipid peroxyl radical forms α-tocopheroxyl radical

It is well established that major antioxidant function of α-TOH is LOO• scavenging38. Scavenging of LOO• by α-TOH is maintained because hydrogen transfer from α-TOH to LOO• is faster than hydrogen transfer from neighboring fatty acid39,40. Due to the stereoelectronic features of α-TOH, the stability of α-TO• formed after the hydrogen transfer from α-TOH to LOO• is relatively high. The reaction between α-TOH and LOO• occurs either through concerted hydrogen transfer or via sequential electron transfer followed by proton transfer to form LOOH and α-TO• (Fig. 4A and B, α-TO• trace). The α-TO• can either be reduced back to α-TOH by another cellular reductant such as ascorbate forming Asc•− (Fig. 4A and B, Asc•− trace) or react with another LOO• forming nonradical products. Tocopherol dimers and trimers may be formed during LOO• scavenging as minor products41.

Continuous antioxidant activity provided by α-TOH depends on reductive regeneration of α-TOH from α-TO• by ascorbate42. It is well established that α-TO• is reduced by ascorbate to α-TOH while Asc•− is formed44,45,46,47,47. Due to continuous regeneration of α-TOH by ascorbate, LOO• scavenging by α-TOH allows suppression of lipid peroxidation at concentrations typically as low as one molecule of α-TOH per thousand phospholipids34,38,49,50,51,52,52.

Relevance for photooxidative stress in Arabidopsis

It was previously demonstrated that herbicide pyrazolynate mediated-inhibition of α-TOH biosynthesis in Chlamydomonas cells under high light stress caused PS II inactivation53. Using WT and vte1 Arabidopsis exposed to high light at low temperature, α-TOH was shown to protect lipids from the photooxidative damage54,55. Our observation that formation of LOOH (Fig. 5A) and POOH (Fig. 5B) in WT was lower compared to vte1 Arabidopsis reveals that α-TOH prevent formation of both LOOH and POOH.

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to contribute to the understanding of in vitro antioxidant mechanisms of α-TOH against photooxidative stress. Detail description of α-TOOH formation by 1O2 chemical quenching and α-TO• formation by LOO•/ROO• scavenging might help to elucidate antioxidant activity of α-TOH in Arabidopsis plants. Mechanism of the cellular antioxidant defense plays a crucial role in regulating the levels of 1O2 and LOO•/ROO• in plants when exposed to a variety of environmental stresses.

References

Krieger-Liszkay, A., Fufezan, C. & Trebst, A. Singlet oxygen production in photosystem II and related protection mechanism. Photosynth. Res. 98, 551–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11120-008-9349-3 (2008).

Telfer, A. Singlet oxygen production by PSII under light stress: mechanism, detection and the protective role of beta-carotene. Plant Cell. Physiol. 55, 1216–1223. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcu040 (2014).

Triantaphylides, C. & Havaux, M. Singlet oxygen in plants: production, detoxification and signaling. Trends Plant. Sci. 14, 219–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2009.01.008 (2009).

Fischer, B. B., Hideg, E. & Krieger-Liszkay, A. Production, detection, and signaling of singlet oxygen in photosynthetic organisms. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 2145–2162. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2012.5124 (2013).

Pospíšil, P. Molecular mechanisms of production and scavenging of reactive oxygen species by photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 218–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.05.017 (2012).

Kruk, J., Hollander-Czytko, H., Oettmeier, W. & Trebst, A. Tocopherol as singlet oxygen scavenger in photosystem II. J. Plant Physiol. 162, 749–757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2005.04.020 (2005).

Munne-Bosch, S. & Alegre, L. The function of tocopherols and tocotrienols in plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 21, 31–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-2689(02)80037-5 (2002).

DellaPenna, D. A decade of progress in understanding vitamin E synthesis in plants. J. Plant Physiol. 162, 729–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2005.04.004 (2005).

Falk, J. & Munne-Bosch, S. Tocochromanol functions in plants: antioxidation and beyond. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 1549–1566. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erq030 (2010).

Krieger-Liszkay, A. & Trebst, A. Tocopherol is the scavenger of singlet oxygen produced by the triplet states of chlorophyll in the PSII reaction centre. J.Exp. Bot. 57, 1677–1684. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erl002 (2006).

Foote, C. S., Chang, Y. C. & Denny, R. W. Chemistry of singlet oxygen. X. Carotenoid quenching parallels biological protection. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 92, 5216–5218 (1970).

Fahrenholtz, S. R., Doleiden, F. H., Trozzolo, A. M. & Lamola, A. A. On the quenching of singlet oxygen by alpha-tocopherol. Photochem. Photobiol. 20, 505–509 (1974).

Kruk, J. & Strzałka, K. Occurrence and function of α-tocopherol quinone in plants. J. Plant Physiol. 145, 405–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0176-1617(11)81762-1 (1995).

Kobayashi, N. & DellaPenna, D. Tocopherol metabolism, oxidation and recycling under high light stress in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 55, 607–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03539.x (2008).

Neely, W. C., Martin, J. M. & Barker, S. A. Products and relative reaction rates of the oxidation of tocopherols with singlet molecular oxygen. Photochem. Photobiol. 48, 423–428 (1988).

Kaiser, S., Di Mascio, P., Murphy, M. E. & Sies, H. Physical and chemical scavenging of singlet molecular oxygen by tocopherols. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 277, 101–108 (1990).

Yamauchi, R. & Matsushita, S. Light-induced lipid peroxidation in isolated chloroplasts and role of α-tocopherol. Agric. Biol. Chem. 43, 2157–2161. https://doi.org/10.1080/00021369.1979.10863773 (1979).

Kruk, J., Szymanska, R. & Krupinska, K. Tocopherol quinone content of green algae and higher plants revised by a new high-sensitive fluorescence detection method using HPLC–effects of high light stress and senescence. J. Plant Physiol. 165, 1238–1247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2008.03.006 (2008).

Spicher, L. & Kessler, F. Unexpected roles of plastoglobules (plastid lipid droplets) in vitamin K1 and E metabolism. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 25, 123–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2015.05.005 (2015).

Munné-Bosch, S. & Alegre, L. The function of tocopherols and tocotrienols in plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 21, 31–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-2689(02)80037-5 (2002).

Smirnoff, N. Tocochromanols: rancid lipids, seed longevity, and beyond. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 17857–17858. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1012749107 (2010).

Mehlhorn, R. J., Fuchs, J., Sumida, S. & Packer, L. Preparation of tocopheroxyl radicals for detection by electron spin resonance. Methods Enzymol. 186, 197–205 (1990).

Witting, P. K., Upston, J. M. & Stocker, R. Role of alpha-tocopheroxyl radical in the initiation of lipid peroxidation in human low-density lipoprotein exposed to horse radish peroxidase. Biochemistry 36, 1251–1258. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi962493j (1997).

Porfirova, S., Bergmuller, E., Tropf, S., Lemke, R. & Dormann, P. Isolation of an Arabidopsis mutant lacking vitamin E and identification of a cyclase essential for all tocopherol biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 12495–12500. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.182330899 (2002).

Casazza, A. P., Tarantino, D. & Soave, C. Preparation and functional characterization of thylakoids from Arabidopsis thaliana. Photosynth. Res. 68, 175–180. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011818021875 (2001).

Arnon, D. I. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts, polyphenoloxidase in beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 24, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.24.1.1 (1949).

Nowicka, B. & Kruk, J. Plastoquinol is more active than alpha-tocopherol in singlet oxygen scavenging during high light stress of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 389–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.12.002 (2012).

Giusepponi, D. et al. LC-MS/MS assay for the simultaneous determination of tocopherols, polyunsaturated fatty acids and their metabolites in human plasma and serum. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 144, 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.04.017 (2019).

Soh, N. Recent advances in fluorescent probes for the detection of reactive oxygen species. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 386, 532–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-006-0366-9 (2006).

Soh, N. et al. Swallow-tailed perylene derivative: a new tool for fluorescent imaging of lipid hydroperoxides. Org. Biomol. Chem. 5, 3762–3768. https://doi.org/10.1039/b713223a (2007).

Grintzalis, K., Zisimopoulos, D., Grune, T., Weber, D. & Georgiou, C. D. Method for the simultaneous determination of free/protein malondialdehyde and lipid/protein hydroperoxides. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 59, 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.09.038 (2013).

Liebler, D. C., Kaysen, K. L. & Kennedy, T. A. Redox cycles of vitamin E: hydrolysis and ascorbic acid dependent reduction of 8a-(alkyldioxy)tocopherones. Biochemistry 28, 9772–9777 (1989).

Schneider, C. Chemistry and biology of vitamin E. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 49, 7–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.200400049 (2005).

Atkinson, J., Epand, R. F. & Epand, R. M. Tocopherols and tocotrienols in membranes: a critical review. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 44, 739–764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.11.010 (2008).

Liebler, D. C., Burr, J. A., Philips, L. & Ham, A. J. Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis of vitamin E and its oxidation products. Anal. Biochem. 236, 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1006/abio.1996.0127 (1996).

Yamauchi, R. & Matsushita, S. Products formed by photosensitized oxidation of tocopherols. Agric. Biol. Chem. 43, 2151–2156. https://doi.org/10.1080/00021369.1979.10863772 (1979).

Yamauchi, R., Kato, K. & Ueno, Y. Reaction of 8a-hydroperoxy tocopherones with ascorbic-acid. Agric. Biol. Chem. 45, 2855–2861. https://doi.org/10.1080/00021369.1981.10864969 (1981).

Burton, G. W. & Ingold, K. U. Vitamin E: application of the principles of physical organic chemistry to the exploration of its structure and function. Acc. Chem. Res. 19, 194–201. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar00127a001 (1986).

Burton, G. W. & Ingold, K. U. Autoxidation of biological molecules. 1. Antioxidant activity of vitamin E and related chain-breaking phenolic antioxidants in vitro. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 103, 6472–6477. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00411a035 (1981).

Burton, G. W. et al. Autoxidation of biological molecules. 4. Maximizing the antioxidant activity of phenols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 107, 7053–7065. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00310a049 (1985).

Yamauchi, R., Matsui, T., Satake, Y., Kato, K. & Ueno, Y. Reaction products of alpha-tocopherol with a free radical initiator, 2,2′-Azobis(2,4-dimethylvaleronitrile). Lipids 24, 204–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02535235 (1989).

Niki, E., Tsuchiya, J., Tanimura, R. & Kamiya, Y. Regeneration of vitamin-E from alpha-chromanoxyl radical by glutathione and vitamin-C. Chem. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1246/cl.1982.789 (1982).

Chan, A. C., Tran, K., Raynor, T., Ganz, P. R. & Chow, C. K. Regeneration of vitamin E in human platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 17290–17295 (1991).

Mukai, K., Nishimura, M. & Kikuchi, S. Stopped-flow investigation of the reaction of vitamin C with tocopheroxyl radical in aqueous triton X-100 micellar solutions. The structure-activity relationship of the regeneration reaction of tocopherol by vitamin C. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 274–278 (1991).

Kamal-Eldin, A. & Appelqvist, L. A. The chemistry and antioxidant properties of tocopherols and tocotrienols. Lipids 31, 671–701 (1996).

Han, D., Yi, O. S. & Shin, H. K. Solubilization of vitamin C in fish oil and synergistic effect with vitamin E in retarding oxidation. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 68, 740–743. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02662163 (1991).

Munne-Bosch, S., Queval, G. & Foyer, C. H. The impact of global change factors on redox signaling underpinning stress tolerance. Plant Physiol. 161, 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.112.205690 (2013).

Kornbrust, D. J. & Mavis, R. D. Relative susceptibility of microsomes from lung, heart, liver, kidney, brain and testes to lipid peroxidation: correlation with vitamin E content. Lipids 15, 315–322 (1980).

Sevanian, A., Hacker, A. D. & Elsayed, N. Influence of vitamin E and nitrogen dioxide on lipid peroxidation in rat lung and liver microsomes. Lipids 17, 269–277 (1982).

Munné-Bosch, S. The role of alpha-tocopherol in plant stress tolerance. J. Plant Physiol. 162, 743–748 (2005).

Niki, E. & Traber, M. G. A history of vitamin E. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 61, 207–212. https://doi.org/10.1159/000343106 (2012).

Salem, H. Oxidants, Antioxidants and Free Radicals (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 1997).

Trebst, A., Depka, B. & Hollander-Czytko, H. A specific role for tocopherol and of chemical singlet oxygen quenchers in the maintenance of photosystem II structure and function in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. FEBS Lett. 516, 156–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02526-7 (2002).

Havaux, M., Eymery, F., Porfirova, S., Rey, P. & Dormann, P. Vitamin E protects against photoinhibition and photooxidative stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 17, 3451–3469. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.105.037036 (2005).

Kumar, A. et al. Interplay between antioxidants in response to photooxidative stress in Arabidopsis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 160, 894–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.08.027 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank Michel Havaux (CEA, Cadarache, France) for stimulating discussions and Jerzy Kruk (Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland) for providing us advice for the α-TQ detection.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) project "Plants as a tool for sustainable global development" (No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000827) and Grant No. IGA_PrF_2020_028 from Palacký University, Olomouc, Czech Republic.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.P. and A.K. contributed to the conception and design of the work; A.K. and A.P. measured the EPR data; A.K. measured the absorption data; A.K. analysed the EPR and absorption data. A.K. and P.P. measured and analysed the fluorescence and HPLC data. A.K. and P.P. made data interpretation. A.P. participated in data interpretation. P.P. and A.K. drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, A., Prasad, A. & Pospíšil, P. Formation of α-tocopherol hydroperoxide and α-tocopheroxyl radical: relevance for photooxidative stress in Arabidopsis. Sci Rep 10, 19646 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75634-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75634-0

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.