Abstract

The quantum walk is the quantum-mechanical analogue of the classical random walk, which offers an advanced tool for both simulating highly complex quantum systems and building quantum algorithms in a wide range of research areas. One prominent application is in computational models capable of performing any quantum computation, in which precisely controlled state transfer is required. It is, however, generally difficult to control the behavior of quantum walks due to stochastic processes. Here we unveil the walking mechanism based on its particle-wave duality and then present tailoring quantum walks using the walking mechanism (Floquet oscillations) under designed time-dependent coins, to manipulate the desired state on demand, as in universal quantum computation primitives. Our results open the path towards control of quantum walks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The random walk1 is a fundamental concept that has been used to describe a variety of systems with inevitable stochastic processes2,3. A classical walker moves one step to the left or one step to the right depending on the outcome of a coin toss. After many coin tosses, the walker’s position is random, but is most likely to be close to the start point. In contrast, a walker in a quantum world4,5 simultaneously travels in both directions, behaving as a quantum wave, forming a coherent superposition of left and right that occupies more than one location at any given time. In addition, quantum interference effects between the possible trajectories of the walker also contribute to modify the resulting dynamics substantially such as delocalization over many steps. Thus, the wave nature of the walker in the particle-wave duality is important for its walking behavior.

The unique features emerging from the wave nature of the quantum walk (e.g., fast spreading6,7) have been predominantly applied to quantum search algorithms8,9,10 in quantum information sciences. Recently, quantum walks have been shown to be universal computational primitives in quantum computation, i.e., any quantum algorithm can be reconstructed as a quantum walk algorithm11,12. Therefore, precise control of quantum state transfer between arbitrary distant sites is critical for quantum information processing13,14,15,16. It is, however, not easy to manipulate quantum states using quantum walks due to their essentially random nature17,18,19. In addition, the walking mechanism in the wave picture is less obvious than that in the particle picture, where the walker shifts its position depending on the coin.

One possible approach to find the walking mechanism in the wave picture for controlling quantum walks might be to manipulate the coin transformation which would then allow us to drive walk evolution in a desired manner. Initially, a space-dependent coin was introduced in the quantum walk20. Later, a quantum walk with time-dependent coins was studied21,22,23,24,25. The resulting probability distribution for the quantum walk changed significantly. This implies that coin transformation is certainly involved in the walking mechanism and explicitly designing the sequence of coin transformations could lead to a desired state transfer.

Results

The time-dependent coined quantum walk

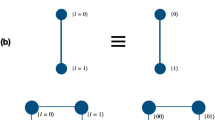

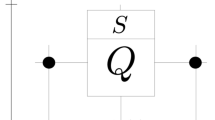

Suppose a walker on a line with a coin living in the Hilbert space of the whole system \({{\mathscr {H}}}={{\mathscr {H}}}_p\otimes {{\mathscr {H}}}_c\), where \({{\mathscr {H}}}_p\) and \({{\mathscr {H}}}_c\) are the Hilbert space of walker’s position with basic vectors \(\{|{m}\rangle ,m\in {\mathbb {Z}}\}\) and of the coin with basic vectors \(\{|{L}\rangle ,|{R}\rangle \}\), respectively. The behavior of the walker in the quantum-mechanical domain is described by two operators. One is the shift operator \({\hat{S}}\) defined as

which shifts walker’s position. Another is the coin operator which transforms the internal state of the coin. Here, we employ the time-dependent coin,

where \(0\le \rho (t)\le 1\). In each step, the walker shifts based on the new internal state of the coin after the transformation from the previous state of the coin. Therefore, the state of the whole system after n steps starting from the initial state \(|{\psi }\rangle _0\) is given by

where the probability amplitudes \(L_{m,n}\) and \(R_{m,n}\) are given as

Here \({\mathbb {I}}\) is the unit matrix and T is the time between steps. Finally, the probability distribution of finding the walker in the position m after n steps, \(P_m(n)\), is given as \(P_m(n)=P_m^L(n)+P_m^R(n) \ \) with \(P_m^L(n)=|L_{m,n}|^2\) and \(P_m^R(n)=|R_{m,n}|^2\).

The numerical simulation of the time-dependent coined quantum walk

Applying the above definitions, we performed numerical simulations on the quantum walk with the time-dependent coin. We employ \(\rho (t)=\cos ^2(\theta _0+\omega t)\) as an example of the time-dependent coin characterized by the coin flipping frequencies \(\omega \) and the initial phases \(\theta _0\). We discovered numerically for the first time that the probability distributions of finding a particle (walker) on a line as a function of both \(\omega \) and \(\theta _0\) parameters exhibit a wide variety of walker’s trajectories representing high probability portions such as loops connected by lines (referred to as loop-line chains, see Fig. 1c) and adjacent loops (loop-loop chains, Fig. 1e,f) as shown in Fig. 1.

With the time-independent coins \((\omega =0)\), as shown in Fig. 1a, a trajectory with linear spreading in space peculiar to the quantum walk is reproduced, supporting our numerical simulations. With the time-dependent coins with finite frequencies \((\omega \ne 0)\), the trajectory forms closed loops. Interestingly, the resulting closed trajectories are not just sequential loops, as expected naturally, but also occur as connected structures of loops alternating with lines (loop-line chains). In addition, loop size tends to decrease as the coin’s frequency increases. Eventually, a linear trajectory with almost no spatial spread can be observed. Moreover, trajectories are also influenced by the initial phase \(\theta _0\). The trajectories in Fig. 1c,e,f with different initial phase values differ from each other even though they have the same \(\omega \) value. Note that the trajectories in Fig. 1e,f are categorized as loop-loop chains, but the origin of the loops is completely different as discussed later.

A wide variety of the walker’s trajectories. The phase diagram (center) with insets indicating probability distributions of walker’s position (upper) and trajectory (lower) over 300 steps at typical parameters for coin with initial phase \(\theta _0\) and frequency \(\omega \), by numerical simulations starting with the initial state of \(|{\psi }\rangle _0=|{0,R}\rangle /\sqrt{2}+i|{0,L}\rangle /\sqrt{2}\). (a) linear spreading \(\theta _0=\pi /4\) and \(\omega =0\), (b) curved spreading \(\theta _0=\pi /4\) and \(\omega =\pi /1000\), (c) a loop-line chain \(\theta _0=\pi /4\) and \(\omega =\pi /60\), (d) a localized line \(\theta _0=\pi /4\) and \(\omega =\pi /10\), (e) a crossing loop-loop chain \(\theta _0=0\) and \(\omega =\pi /60\), (f) a touching loop-loop chain \(\theta _0=3\pi /2\) and \(\omega =\pi /60\), (g) walker’s trajectories in a crossing loop-loop chain predicted by the analytic solution, (h) walker’s trajectories in a touching loop-loop chain predicted by the analytic solution. Loop-loop chains appear as crossing chains only at \(\theta _0=n\pi \) (red lines) and as touching chains only at \(\theta _0=(2n+1)\pi /2\) (blue lines) in the phase diagram (where \(n=\)integer).

It was found that these features can be reproduced with a simple formula in a numerical analysis, i.e., the trajectory \(x_c\) is well fitted by the sinusoidal function expressed as \(x_c=a\sin (\phi _0+\Omega t)+b\) where a, b, \(\phi _0\) and \(\Omega \) are the amplitude, the bias, the initial phase and the frequency, respectively. Figure 2 shows the fitting parameters a, \(\phi _0\), \(\Omega \), and b as a function of both the initial phase \(\theta _0 \) with fixed frequency \(\omega =\pi /60\) (top row) and the frequency \(\omega \) with an initial phase of \(\theta _0=\pi /4\) (middle row). From each pair of the \(\theta _0\) and \(\omega \) rows, the physical origin of the fitting parameters can be inferred as shown in the bottom row. These fitting parameters provide an excellent clue to elucidating the walking mechanism.

Fitting parameters. The fitting parameters of a trajectory in the form of \(x_c=a\sin {(\phi _0+\Omega t)}+b\) are represented by blue points (the numerical simulation results) and a red line (the analytical result) in each graph. The parameters (the amplitude a, initial phase \(\phi _0\), frequency \(\Omega \), and bias b) are shown as a function of both the initial phase \(\theta _0 \) with fixed frequency \(\omega =\pi /60\) (top row) and the frequency \(\omega \) with an initial phase of \(\theta _0=\pi /4\) (bottom row). (a) and (A) for the amplitude, (b) and (B) for the initial phase, (c) and (C) for the frequency, and (d) and (D) for the bias.

The analytic solution of the time-dependent coined quantum walk

Here we derive the analytic solution to a quantum walk with a time-dependent coin based on the seminal work by Knight et al.26 together with its extended work to time-dependent coins by Banũls et al.21, in order to explore the walking mechanism of its trajectories. From the time evolution of the probability amplitudes in Eqs. (4) and (5) by setting \(\rho (nT)=\cos ^2\theta _n\) with \(\theta _n=\theta _0+n\omega T\), we obtain the difference equation,

where \(A=L, R\). By introducing a continuum field of space and time \(A^{\pm }(x,t)\) to take the wave propagation in both positive and negative directions into account26, we obtain the differential equation within the long-wavelength approximation,

where \(\xi \) and \(\tau \) are normalized coordinate and time, respectively. The analytic solution is expressed by

with

where \({{\text {Ai}}}(x)\) stands for the Airy function and 2w is the standard deviation of the Gaussian function introduced to describe spreading waves. A detailed solution to Eq. (7) is provided in the Method. The probability distribution \(P(\xi ,\tau )\) is then obtained by \(P(\xi ,\tau )=P^{L}(\xi ,\tau )+P^{R}(\xi ,\tau )\) where \(P^{A}(\xi ,\tau )=|A^{+}(\xi ,\tau )+(-1)^{n}A^{-}(\xi ,\tau )|^2\) with \(A=L, R\). These results are essentially the same as Bañuls’s except for the difference in the coin operators.

Figure 3 shows the probability distributions of finding the walker on a line, based on the numerical simulation and the analytical solution. It can be seen that the analytical solutions agree well with the numerical solutions, showing that the long-wavelength approximation analysis works very well. However, there is one missing link between the two solutions. In the analytical solution, the linear spreading inherent in the quantum walk is not reproduced and remains unsolved.

Walking mechanism

Now let us discuss walking mechanism that has not been clarified so far by considering the walker’s trajectories. The essentials of the probability distribution are described by \(A^{\pm }(\xi ,\tau )\) expressed in the Fourier form as

by using the shifted probability amplitude \(B^{\pm }(\xi ,\tau )\)

Equation (13) means that the entire distribution \(A^{\pm }\left( \xi ,\tau \right) \) shifts with \(\mp \int _{0}^{\tau }\cos {\theta (\tau ')}d\tau '\) over time. Therefore the trajectory is given by a simple sinusoidal function

This analytical result shows complete agreement with the results obtained by numerical analysis.

This agreement allows us to interpret the various trajectories seen in Fig. 1 using the analytical solution. Surprisingly, all the trajectories can be described by two sinusoidal functions in Eq. (15). The bias \(b=-\sin {\theta _0}/\omega \) determines the relative overlap between two sinusoidal functions, leading to various types of chain structures. The crossing loop-loop chains with loops of the same size as shown in Fig. 1g appear when the overlaps occur at \(\theta _0=n\pi \) \((n=\text{ integer})\) depicted by the red lines in the middle panel of Fig. 1. In addition, at \(\theta _0=(n+1)\pi /2\) (the blue lines in the middle panel of Fig. 1), a second type of chain is created by adjacent rather than intersecting sinusoidal functions as shown in Fig. 1h, otherwise the loop-line chains appear instead. Actually, the linear part that seems to be a straight line is the area where the sinusoidal functions overlap. Therefore, the loop-line structure can be described as a chain of loops of two sizes that alternate. On the other hand, frequency \(\omega \) determines the size of the loop that depends on \(\omega \) in time and \(1/\omega \) in space. Thus, the loop becomes smaller when the frequency increases, resulting in narrower trajectories. In this way, through the analytical solution, we obtain a unified view of the probability distribution trajectory shown in Fig. 1.

Now let us discuss the physical origin of trajectories obtained above. Based on Eq. (7), the quantum walk eventually behaves like a quantum-mechanical wave. According to wave theory, there is a well-known dispersion relation, \(\omega = v k\), between the wave number k and frequency \(\omega \). From Eq. (7), the component of the coin operator, \(\mp \cos \theta (\tau )\), appears in the place corresponding to the velocity of this wave. This shows that the coin in the wave picture of the quantum walk plays the role of the speed of the quantum wave that determines the walking trajectory. This is the walking mechanism of the quantum walk hidden behind the wave picture. This is one of our central results of this paper.

The numerical simulation and the corresponding analytical solution. Probability distributions and their trajectories for the quantum walk with initial state \(|{\psi }\rangle _0=|{0,R}\rangle /\sqrt{2}+i|{0,L}\rangle /\sqrt{2}\) (\(R_{0,0}=1/\sqrt{2}\) and \(L_{0,0}=i/\sqrt{2}\)), coin initial phase \(\theta _0=\pi /4\), and frequency \(\omega =\pi /60\) over 300 steps. The graph on the left shows the result of the numerical simulation, and the graph on the right shows the result of the analytic solution with \(w=0.4\). Note that the linear spatial spreading is shown in the probability distribution of the numerical simulation only.

This correspondence can also be confirmed in the particle picuture. We reconsider the walking mechanism based on the Hamiltonian formalism from the viewpoint of the particle nature in the particle-wave duality. The Hamiltonian for generating one-dimensional discrete time quantum walk can be derived from the walker’s time evolution operator \(W\equiv SC=\exp [-iH\tau ]\) for each step of the walk on the discrete position space and is given as \(H(k)={\varvec{h}}(k)\cdot {\varvec{\sigma }}\) in the two-component Dirac-like Hamiltonian form where \({\varvec{h}}(k)\) and \({\varvec{\sigma }}\) are a three-dimensional wavenumber k-dependent vector and the vector of the Pauli spin matrices, respectively. Specific expressions for the coin operators we have adopted are given in the reference27 creating cat states in one-dimensional quantum walks using delocalized initial states.

Since the vector \({\varvec{h}}(k)\) contains information on the coin operator depending on the periodic function in time, the Hamiltonian naturally has the translational invariant under a discrete time translation \(H(\tau )=H(\tau +T)\). This allow us to use the Floquet formalism. According to the Floquet theorem, the Floquet state solution \(\Phi _\alpha (x,t)\) for the quasienergy \(\epsilon _\alpha \) is given by the solution of the eigenvalue equation \({{{{\mathscr {H}}}}_F}(x,t)\Phi _\alpha (x,t)=\epsilon _\alpha \Phi _\alpha (x,t)\) with the Floquet Hamiltonian \({{{{\mathscr {H}}}}_F}=H(x,t)-i\partial /\partial t\).

For our system, the quasienergy \(\epsilon _{\pm }\) for the 1st Floquet zone27 is given in the same approximation as the long wavelength approximation adopted above:

Since the velocity operator is given by the Heisenberg equation \({\hat{v}}=\dot{{\hat{x}}}=[{{{{\mathscr {H}}}}_F},{\hat{x}}]\), the diagonal terms of the velocity representing the left and right propagating waves read \(\langle {\hat{v}}_{\alpha }\rangle = v_{\alpha }=d\epsilon _\alpha /dk\). From these, we reconfirm that the velocity of the particle coincides with the wave velocity \(\mp \cos \theta \) obtained in the wave picture. Therefore, quantum walk with time-dependent coins can be regarded as a quantum particle oscillating in the Floquet band. This is the counterpart of quantum walks with space-dependent coins causing Bloch oscillations in periodic band structures.

The general time-dependent coined quantum walk

So far we have discussed the dynamics of quantum walks with specific time-dependent coins and clarified the physical origin behind the quantum walk. Finally, we formulate the quantum walk for an arbitrary time-dependent coin, and discuss the controllability of the quantum walk. We employ the coin with general time dependence in a unitary form \(\rho (t)=\cos ^2(\Phi (t))\) with

where \(q_l\) is the Fourier coefficient. The time-dependent phase \(\Phi (t)\) can express an arbitrary function. Through procedures parallel to those described above, we obtain the trajectory expressed as

where

with \(K=k_1+2k_2+\cdot{\mkern -4mu}\cdot{\mkern -4mu}\cdot +jk_j\). Eq. (18) is nothing but a Fourier series expansion and is the central result of this paper. The implication of Eq. (18) is that walker’s trajectory can take any path. Therefore, we can obtain the desired trajectory through designing the coin operator. This is another significant result of this paper. Figure 4 shows one such example with a coin depending on \(\Phi (t)=\frac{1}{4}\sin {(\omega t)}+\frac{1}{3}\sin {(2\omega t)}+\frac{1}{2}\sin {(3\omega t)}+\sin {(4\omega t)}\). The the analytic solutions replicates the numerical simulations.

Probability distributions of quantum walks with a general time-dependent coin. Probability distributions of a quantum walk with initial state \(|{\psi }\rangle _0=|{0,R}\rangle /\sqrt{2}+i|{0,L}\rangle /\sqrt{2}\) (\(R_{0,0}=1/\sqrt{2}\) and \(L_{0,0}=i/\sqrt{2}\)), and coin depending on \(\Phi (t)=\frac{1}{4}\sin {(\omega t)}+\frac{1}{3}\sin {(2\omega t)}+\frac{1}{2}\sin {(3\omega t)}+\sin {(4\omega t)}\) over 300 steps. The graph on the left shows the result of the numerical simulation, and the graph on the right shows the result of the analytic solution with \(w=0.4\).

Discussion

In summary, quantum walks with arbitrary time-dependent coins have been studied both numerically and analytically. The numerical simulations have been reproduced almost perfectly by the analytical solutions, and together have revealed the walking mechanism hidden in the quantum walks in the wave picture, i.e., that the coin flipping rate plays the role of the wave speed of the quantum walk governing the walker’s trajectories. This wave behavior can also be interpreted as Floquet oscillations in periodic energy bands in the particle picture. Based on this walking mechanism, the walker’s trajectory has been proved to be represented by the Fourier series of coins. Therefore, the walking mechanism enables us to tailor quantum walks as we desire through manipulating the coin flipping rate. Our results open the path towards the control of quantum walks.

Methods

Analytical solutions

In the supplement, we show our analytic solution for predicting the probability distribution of the walker’s location for quantum walks with a time-dependent coin. According to Bañuls’s extended theory21 which is based on the seminal work of Knight et al.26, the time evolution of the probability amplitudes is given by

We derive recurrence formulas of \(R_{m,n}\) and \(L_{m,n}\) by using Eqs. (21) and (22),

where \(S_n\equiv \sin {\theta _n}\) and \(C_n\equiv \cos {\theta _n}\). These (for \(A_{m,n} = R_{m,n}\) or \(L_{m,n}\)) can be rewritten as

by using the following relations,

where \(C_n^{\pm }=\cos \theta _n^{\pm }\) and \(S_n^{\pm }=\sin \theta _n^{\pm }\) are denoted with \(\theta _n=\theta _n^{+}+\theta _n^{-} \text{ and } \theta _{n-1}=\theta _n^{+}-\theta _n^{-}.\) Since trigonometric functions are approximated as \(S_n^{-}\simeq 0\), \(C_n^{-}\simeq 1\), \(S_n^{+}\simeq \sin {\theta _n}\), and \(C_n^{+}\simeq \cos {\theta _n}\) under small \(\theta _n^{\pm }\), the difference equation, Eq. (6), in the main content is expressed as

By introducing a continuum field A(x, t) instead of the discrete field \(A_{m,n}\), Eq. (30) can also be expressed in the Taylor expansion series as

where \(\cos {\theta (t)}\) is a continuum function that replaces \(\cos {\theta _n}\) . Keeping only the first few, lowest order terms, this reduces to

Since Eq. (32) describes a wave that propagates in only one direction (according to linear wave theory), an auxiliary field \(A_{m,n}^{\pm }\) (in discrete systems) that travels in both directions was originally required to preserve the symmetry of the system. After introducing the dimensionless variables \(\xi \) and \(\tau \), this results in

To obtain an analytical solution for the partial differential equation in Eq. (33), we adopt the usual method of solving partial differential equations using the Fourier method and assume \(A^{\pm }(\xi ,\tau )\) with functions \(G_m(\xi )\) and \(A_m^{\pm }(\tau )\) in the variable-separated form,

with a normalization factor N. By using the Fourier transformation from the wavenumber k space,

the partial differential equation, Eq. (33), reduces to the ordinary differential equation

Equation (37) can be immediately solved as

where

To find \(A^{\pm }(k,0)\) in Eq. (38), we perform inverse Fourier transformations on Eq. (36) by setting \(\tau =0\), which yields

where

with \(A_m^{\pm }(0)=A_{m,0}^{\pm }\). Since the Gaussian integral is given as

Eq. (40) reduces to

where the prefactor of the Gaussian integral \(N\sqrt{4w^2\pi }\) is omitted in the following because it is merely a scaling factor. Substituting Eq. (43) into Eq. (38), \(A^{\pm }(k,\tau )\) is rewritten as

Therefore, \(A^{\pm }(\xi ,\tau )\) in Eq. (36) can be expressed by

where

\(Z^{\pm }(\xi ',\tau )\) can be represented using existing analytical functions as follows

where \(\xi ' \equiv \xi -m\).

Note that the relation \(Z^{-}(\xi ',\tau )=Z^{+}(-\xi ',\tau )\) holds between \(Z^{+}(\xi ',\tau )\) and \(Z^{-}(\xi ',\tau )\). By using the Airy function \({{\text {Ai}}}(x)\),

\(Z^{+}(\xi ',\tau )\) is expressed as

where

Finally, let us consider the initial coefficients \(A^{\pm }_{m,0}\) in Eq. (45). According to the relation \(A_{m,n}\equiv A_{m,n} ^{+}+(-1)^m A_{m,n} ^{-}\) proposed by Knight et al., the following relations

lead to the simple relation

Using this relation, we obtain

Suppose that the walker starts at \(m=0\), then the initial condition

leads to

As a result, Eq. (8) reduces to

Thus, we have obtained an analytic solution to quantum walks with a time-dependent coin that is essentially the same as the solution of Bañuls et al. except for the difference in the coin operators.

Based on the above elementary results, let us now derive the analytical solution for the quantum walks with the generalized time-dependent coins in a unitary form using \(\rho (t)=\cos ^2(\Phi (t)))\) in the same manner as before. We start from the recurrence formulas Eq. (25) replacing \(\theta _n\) with \(\Phi _n(=\sum _{l=1}^{j}q_l\sin {(nl\omega T)})\). Since trigonometric functions are approximated as \(S_n^{-}\simeq 0\), \(C_n^{-}\simeq 1\), \(S_n^{+}\simeq \sin {\Phi _n}\), and \(C_n^{+}\simeq \cos {\Phi _n}\) under small \(\Phi _n^{\pm }\), the difference equation is expressed as

Then we obtain the wave equation in the continuum limit,

Since the velocity of the wave corresponds to \(\mp \cos {\Phi (\tau )}\) in the above equation, the walker’s trajectory is described by the integral of the velocity over a defined interval as follows,

Before proceeding with the integration, let us prove the following relations by using mathematical induction,

where \(J_{k_l}(q_l)\) is the Bessel function of the first kind of order \(k_l\) of \(q_l\). First, at \(j=1\), the equations are

Thus, Eqs. (63) and (64) are established with certainty. Assuming that Eqs. (63) and (64) are correct at \(j=p\), we show that the relations also hold at \(j=p+1\). At \(j=p+1\) we obtain the relations for Eq. (63) as follows,

demonstrating that Eq. (63) is true. Therefore, we confirm that Eq. (63) is established for any natural number p. In the same way, it can be shown that Eq. (64) is also correct. The trajectory Eq. (62) is rewritten as

with \(K=k_1+2k_2+\cdot{\mkern -4mu}\cdot{\mkern -4mu}\cdot +jk_j\). By using the relation

the walker’s trajectory of quantum walks with generalized time-dependent coin is expressed as

where

This is one of the central results of this paper. Thus, we can control, in general manner, the walker’s trajectory in quantum walks even with time-dependent coins.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Change history

17 March 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-85564-0

References

Pearson, K. The problem of the random walk. Nature 72, 294 (1905).

Kac, M. Random walk and the theory of brownian motion. Am. Math. Monthly 54, 369–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029890.1947.11990189 (1947).

Fama, E. F. Random walks in stock market prices. Financ. Anal. J. 51, 75–80. https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v51.n1.1861 (1995).

Gudder, S. P. Discrete quantum mechanics. In Quantum Probability, Probability and Mathematical Statistics 245–302 (Academic Press, 1988).

Aharonov, Y., Davidovich, L. & Zagury, N. Quantum random walks. Phys. Rev. A 48, 1687–1690 (1993).

Venegas-Andraca, S. E. Quantum walks: a comprehensive review. Quantum Inf. Process. 11, 1015–1106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11128-012-0432-5 (2012).

Kempe, J. Quantum random walks: an introductory overview. Contemporary Phys. 44, 307–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/00107151031000110776 (2003).

Grover, L. K. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search.Proceedings of the Twenty-eighth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing 212–219, https://doi.org/10.1145/237814.237866 (ACM, New York, 1996).

Shenvi, N., Kempe, J. & Whaley, K. B. Quantum random-walk search algorithm. Phys. Rev. A 67, 052307 (2003).

Childs, A. M. & Goldstone, J. Spatial search by quantum walk. Phys. Rev. A 70, 022314 (2004).

Childs, A. M. Universal computation by quantum walk. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 180501 (2009).

Lovett, N. B., Cooper, S., Everitt, M., Trevers, M. & Kendon, V. Universal quantum computation using the discrete-time quantum walk. Phys. Rev. A 81, 042330 (2010).

Kurzyński, P. & Wójcik, A. Discrete-time quantum walk approach to state transfer. Phys. Rev. A 83, 062315 (2011).

Zhan, X., Qin, H., Bian, Z.-H., Li, J. & Xue, P. Perfect state transfer and efficient quantum routing: a discrete-time quantum-walk approach. Phys. Rev. A 90, 012331 (2014).

Yalçınkaya, I. & Gedik, Z. Qubit state transfer via discrete-time quantum walks. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 48, 225302 (2015).

Chen, T., Wang, B. & Zhang, X. Controlling probability transfer in the discrete-time quantum walk by modulating the symmetries. New J. Phys. 19, 113049. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/aa8fe4 (2017).

de Valcárcel, G. J., Roldán, E. & Romanelli, A. Tailoring discrete quantum walk dynamics via extended initial conditions. New J. Phys. 12, 123022. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/12/12/123022 (2010).

Albertini, F. & DAlessandro, D. Controllability of quantum walks on graphs. Math. Control Signals Syst. 24, 321–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00498-012-0084-0 (2012).

Nitsche, T. et al. Quantum walks with dynamical control: graph engineering, initial state preparation and state transfer. New J. Phys. 18, 063017. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/18/6/063017 (2016).

Wójcik, A., Łuczak, T., Kurzyński, P., Grudka, A. & Bednarska, M. Quasiperiodic dynamics of a quantum walk on the line. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 180601 (2004).

Bañuls, M.-C., Navarrete, C., Perez, A., Roldán, E. & Soriano, J. Quantum walk with a time-dependent coin. Phys. Rev. A 73, 062304 (2006).

Albertini, F. & DAlessandro, D. Analysis of quantum walks with time-varying coin on d-dimensional lattices. J. Math. Phys. 50, 122106. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3271109 (2009).

Xue, P. et al. Experimental quantum-walk revival with a time-dependent coin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 140502 (2015).

Cedzich, C. & Werner, R. F. Revivals in quantum walks with a quasiperiodically-time-dependent coin. Phys. Rev. A 93, 032329 (2016).

Panahiyan, S. & Fritzsche, S. Controlling quantum random walk with a step-dependent coin. New J. Phys. 20, 083028. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/aad899 (2018).

Knight, P. L., Roldán, E. & Sipe, J. E. Propagating quantum walks: The origin of interference structures. J. Mod. Opt. 51, 1761–1777. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500340408232489 (2004).

Zhang, W.-W., Goyal, S. K., Gao, F., Sanders, B. C. & Simon, C. Creating cat states in one-dimensional quantum walks using delocalized initial states. New J. Phys. 18, 093025. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/18/9/093025 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank Munehiro Nishida and Kristine H. Onishi for helpful discussions. This work was supported in part by grant from Okawa Foundation for Information and Telecommunications(18-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.K., N.H. and T.F. contributed equally to the current paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Katayama, H., Hatakenaka, N. & Fujii, T. Floquet-engineered quantum walks. Sci Rep 10, 17544 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74418-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74418-w

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.