Abstract

There are few studies on the concentrations and emission characteristics of ammonia (NH3) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) from Chinese dairy farms. The purpose of this study was to calculate the emission rates of NH3 and H2S during summer and to investigate influencing factors for NH3 and H2S emissions from typical dairy barns in central China. Eleven dairy barns with open walls and double-slope bell tower roofs from three dairy farms were studied. Five different locations in each barn were sampled both near the floor and at 1.5 m above the floor. Concentrations of NH3 and H2S were measured using the Nessler’s reagent spectrophotometry method and the methylene blue spectrophotometric method, respectively. NH3 concentrations varied between 0.58 and 4.76 mg/m3 with the average of 1.54 mg/m3, while H2S concentrations ranged from 0.024 to 0.151 mg/m3 with the average of 0.092 mg/m3. The concentrations of NH3 and H2S were higher during the day than at night, and were higher near the ground than at the height of 1.5 m, and were higher in the manure area than in other areas. NH3 and H2S concentrations in the barns were significantly correlated with nitrogen and sulfur contents in feed and manure (P < 0.05), and with temperature inside the barns (P < 0.05). Calculated emission rates of NH3 ranged from 13.8 to 41.3 g NH3/(AU·d), while calculated emission rates of H2S ranged from 0.15 to 0.46 g H2S/(AU·d). These results will serve as a starting point for a national inventory of NH3 and H2S for the Chinese dairy industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global production and consumption of animal products will continue to expand1. However, animal production has been linked to a number of contentious environmental issues in recent decades, including soil erosion, production of global greenhouse gases and atmospheric pollution2,3. For example, emission of ammonia (NH3) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) from livestock production contributes to atmospheric pollution4,5. Thus, this has to be addressed from regulatory and environmental standpoints. Livestock production contributes 64% of total anthropogenic NH3 emissions on a global scale4. The exact number for the contribution of H2S from livestock production in China or in the world is not available. In Denmark, H2S from agricultural sources becomes a more significant fraction for the total sulfur emissions to the atmosphere, as power generation and combustions become cleaner and emit less sulfur dioxide (SO2)5. Among different livestock species, contribution of dairy farming to NH3 and H2S emission is significant. Dairy farming contributed about 50% of the total NH3 emission in the Netherlands6. China has become the world’s largest source of ammonia (NH3) emissions from livestock production (about 7.3 Teragram per year) and of this, 7% of the emissions could be from dairy cows7. In 2016, China had 12.72 million of dairy cows, ranking the third after India and Brazil in the world8. With the increasing demand of milk products per capita and continuous expanding of dairy farming in China, the emission of NH3 and H2S caused by dairy farming is expected to further increase. Henan province, located in the central China, is one of the five major dairy producing areas and one of air heavily polluted regions in China9. The amounts of NH3 and H2S produced and released from dairy farms could be large. Therefore, it is necessary to accurately estimate the NH3 and H2S produced by the dairy farming in this region to assess its impact on the environment pollution.

Gaseous NH3 and H2S from animal production come from decomposition of nitrogen- and sulfur- containing compounds in excrement. NH3 is an important odor gas in the livestock barns as well as an important neurotoxic substance10. Emitted H2S is formed by anaerobic degradation of sulphur-containing organic compounds, especially proteins11. Hydrogen sulfide is a prominent gaseous constituent in animal buildings and manure storage12. It has been considered as the most dangerous gas from livestock production systems and it is responsible for deaths of animals and farm workers in animal facilities13,14. Chronic exposure to H2S can lead to respiratory diseases, eye diseases, and neurological diseases15. With a density higher than air, H2S tends to accumulate in the poorly ventilated areas which exacerbates its hazardous impact. Emission of H2S also contributes to the atmospheric burden of sulfur compounds, which have a major role in the formation of secondary aerosols through oxidation and conversion to aerosol sulfate16,17.

Generation of NH3 and H2S in dairy barns is affected by several factors such as manure production and storage, manure disturbance, ambient temperature, and air exchange rate18,19,20. The concentration of gases inside barns is especially affected by a ventilation system and building structures, which are usually designed to regulate room temperature, especially during summer. Emissions of NH3 and H2S from dairy farms in China may significantly differ from those in other regions such as Europe and the United States due to differences in climatic conditions, feeding methods, rations and configuration of dairy barns. Except in the Northeastern region, dairy barns in most parts of China have bell tower roofs and rely on wind pressure or thermal buoyancy for natural ventilation. Axial fans and sprinkler systems are also installed to help reducing the heat load during summer. Atmospheric NH3 and H2S from animal production have negative effects on health of animals and humans and the ecosystem21. From a policy perspective, governments need to have accurate estimates of emissions and fate of NH3 and H2S in their jurisdictions. Due to the technique difficulty and high expense of field studies, most reported emission rates of NH3 and H2S were calculated from models. There was only one field study for NH3 emissions from dairy farms in the Northern China22. While the inverse dispersion technique in combination with an open-path tunable diode laser used in that study22 is sensitive and fast, it is highly dependent on the meteorological conditions with big variations of determined values in addition to the need of the special equipment. The chemical methods used in this study provide higher accuracy of the gas concentrations. However, they are more time-consuming and labor-intensive. There are no reported measurements of H2S emissions from Chinese dairy farms. As a first tempt to provide accurate and reliable estimation of NH3 and H2S emissions from Chinese dairy farms, this study aimed to understand emission patterns of NH3 and H2S in typical open barns during summer in central China, in order to provide the basis for emission reduction and regulation of NH3 and H2S for the dairy industry in China.

Results

Environmental parameters

As shown in Table 1, the average of indoor temperature was significantly lower than the average of outdoor temperature by 5.3 °C. On the other hand, the relative humidity, the average of wind speed and CO2 concentrations were significantly higher inside the barn than outdoor by 14.7%, 47.2% and 24.4%, respectively. There was no significant difference of the average of air pressure and total suspended particles (TSP) inside or outside of the dairy barns. Diel changes of temperature and humidity for indoor and outdoor were shown in Fig. 1. During the experimental periods, the indoor temperature was lower than the outdoor temperature, while the indoor humidity was higher than the outdoor humidity.

Diel changes of indoor and outdoor temperature and humidity. For each barn, measurement was performed at 2 outside locations (2 upwind blank areas 20 m away from the barn) and 5 inside locations (2 cow bed locations, 2 manure areas and 1 feeding alley) as indicated in Fig. 6. Each location was sampled both near the floor and at 1.5 m above the floor. Measurements were made every 2 hours for two days. The values for temperature and humidity in the figure represent the average of the values measured near the floor and at 1.5 m above the floor.

Concentrations and diel changes of NH3 and H2S

As shown in Table 2, the average of indoor NH3 concentration (1.54 mg/m3) for 11 dairy barns was 60.4% higher than that outside (0.96 mg/m3) of the barns (P < 0.05) during the 48 hours of measurement. In addition, the average NH3 concentration inside the 6 lactating barns (2.13 mg/m3) was 156.6% higher than that inside the 5 non-lactating barns (0.83 mg/m3) (P < 0.05). Similarly, the average of the indoor H2S concentration (0.092 mg/m3) for 11 dairy barns was 240.7% higher than that outside (0.027 mg/m3) of the barns (P < 0.05) (Table 3). The average H2S concentration inside the 6 lactating barns (0.125 mg/m3) was 140.4% higher than that inside the 5 non-lactating barns (0.052 mg/m3) (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

Figure 2 shows the diel changes of NH3 and H2S concentrations in lactating barns measured both near the floor and at 1.5 m above the floor as well as the diel change of the temperature inside the barns at 1.5 m above the floor. The concentrations of NH3 and H2S during daytime were higher than those during night. The concentrations of NH3 and H2S near the floor were higher than those measured at the height of 1.5 m above the floor. In addition, the diel changes of NH3 and H2S concentrations near the floor were parallel to the diel change of the temperature inside the barns. There were no significant diurnal variations in NH3 and H2S concentrations measured at 1.5 m above the floor (P > 0.05), possibly due to lower concentrations and the stable wind from the axial flow fans.

Diel changes of NH3 and H2S concentrations as well as the temperature inside the dairy barns. For each barn, measurement of NH3 and H2S was performed at 2 outside locations (2 upwind blank areas 20 m away from the barn) and 5 inside locations (2 cow bed locations, 2 manure channel locations and 1 feeding alley location) as indicated in Fig. 6. Each location was sampled both near the floor and at 1.5 m above the floor. Measurements were made every 2 hours for 48 hours. The values for NH3 and H2S represent the average of each sampling time point during a day for each height. The values for indoor temperature represent the average of the values measured both near the floor and 1.5 m above the floor.

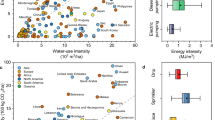

As shown in Fig. 3, there were significant differences in NH3 and H2S concentrations among different locations of the dairy farm. The average NH3 concentration in the manure area was 4.27 ± 1.25 mg/m3, which was significantly higher than those for all other areas (P < 0.05). The average NH3 concentrations among the blank area (0.96 ± 0.67 mg/m3), cow bed (1.11 ± 0.31 mg/m3), and feeding alley locations (1.36 ± 0.86 mg/m3) were not significantly different and were significantly lower than those at manure area and manure storage area (P < 0.05). Similarly, the H2S concentration at the manure area (0.167 ± 0.015 mg/m3) was the highest and significantly higher than those from other locations (P < 0.05). The lowest concentration of H2S was found in the blank area, being only 0.027 ± 0.016 mg/m3, which was significantly lower than those in the other areas (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference (P > 0.05) of H2S among the manure storage area (0.112 ± 0.015 mg/m3), cow bed (0.115 ± 0.013 mg/m3), and feeding alley (0.116 ± 0.012 mg/m3).

Comparison of NH3 and H2S concentrations at different locations inside and outside of dairy barns. Measurement was performed at 36 outside locations (11 exercising areas, 3 manure storage areas and 22 upwind blank areas 20 m away from the barn) and 55 inside locations (22 cow bed locations, 22 manure areas and 11 feeding alley). Each location was sampled both near the floor and at 1.5 m above the floor. Measurements were made every 2 hours for 48 hours. The NH3 or H2S concentrations were the average of the values measured both at 0 m and 1.5 m during 48 hours. The different letters within the same panel are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Influence of feed N and S contents and environment parameters on NH3 and H2S concentrations

Emissions of NH3 and H2S in the dairy barns are often related to the nutrition level of the feed, the environmental factors and manure management. This study investigated relationships between the concentrations of NH3 and H2S and the following factors: the N content in the feed (Nf), N content in manure (Nm), N content in the urine (Nu), S content in the feed (Sf), S content in manure (Sm), S content in urine (Su), indoor temperature (Tin), indoor wind speed W, CO2 and TSP concentrations.

According to the Pearson correlation analysis, the coefficient r values with indoor NH3 concentrations for Nf, Nm, Nu, and Tin were 0.912, 0.884, 0.844 and 0.781, respectively and all the correlations were highly significant (P < 0.01). Similarly, the correlation between indoor H2S concentrations and Sf, Sm, Su, and Tin were significant (P < 0.01) and their r values were 0.959, 0.961, 0.949 and 0.857, respectively. On the other hand, the correlation between indoor NH3 or H2S concentrations and W, CO2 and TSP were not significant (P > 0.05). Consequently, these variables (W, CO2 and TSP) were excluded for further modeling analyses.

A stepwise regression method was used to eliminate the influence of the multi-collinearity of independent variables on the accuracy of the model. Consequently, the regression models were obtained as Eqs 1 and 2 and such models were proved reliable through both the F test and the Durbin Watson test.

CNH3 and CH2S stand for the concentration of NH3 or H2S, respectively.

NH3 and H2S emission rates

The emission rates of NH3 and H2S were determined by both CO2-Balance method and the wind pressure and temperature difference forces method (WT method). The animal unit (AU) is defined as a 500 kg dairy cow. As shown in Table 4, the emission rates of both NH3 and H2S in lactating barns were higher than those in non-lactating barns. The NH3 emission rate in the lactating barns was higher than that in non-lactating barns by 30.4% according to the CO2-balance method. Similarly, the H2S emission rate in the lactating barns was higher than that in non-lactating barns by 18.4% according to the CO2-balance method.

Discussion

NH3 and H2S concentrations

Our research showed that the NH3 concentrations from our dairy barns during summer ranged from 0.58 to 4.76 mg/m3 with an average of 1.54 mg/m3. The average of 6 lactating barns was 2.13 mg/m3 and the average of 5 non-lactating barns was 0.83 mg/m3. The results were significantly lower than those reported by Maasikmets et al.18 (8.10–19.94 mg/m3) in Estonia and slightly lower than those reported by Ngwabie et al.19,23 (2.43 ± 0.99 mg/m3 and 3.11 ± 0.83 mg/m3) in the South of Sweden. Good ventilation from the natural ventilation assisted with axial fans and the spray cooling system could be the reason for the lower NH3 concentrations in our study. The unique barn structure with no walls and a double-slope bell tower shaped roof increases the air flow in the barn, and accelerates the gas exchange with the outside of the barn. The airflow inside the barn could create a relatively negative pressure environment inside the barn, as shown in Fig. 4. The fans accelerated the airflow. At the same time, the small water droplet from the sprinklers could dissolve a certain amount of NH3 and H2S and thus reduce the NH3 and H2S concentrations inside the barn.

Cow barns. (a) A picture of a typical dairy barn; (b) The diagram of ventilation through a bell tower shaped roof; (c) Axial fans and the sprinkler cooling system. Each barn has several axial fans installed 3 m above the floor, while the spraying device was installed 2 m above the floor, which could spray water droplets of 10 μm in diameter.

The indoor H2S concentrations ranged from 0.024 to 0.151 mg/m3 with an average of 0.092 mg/m3. The average of 6 lactating barns was 0.125 mg/m3 and the average of 5 non-lactating barns was 0.052 mg/m3 in this study. Our indoor H2S concentrations were similar to those reported by Maasikmets et al.18 (0.090–0.188 mg/m3) and Clark et al.24 (0.145 mg/m3), due to good ventilation as discussed above. With a density higher than air, H2S tends to accumulate in poorly ventilated areas. H2S is only emitted when manure is disturbed through different handling processes25. Incidences of death caused by H2S have been reported for both animals12,26 and humans14,27. These deaths all happened during mixing of manure. Although the concentration of H2S in this study is not high, the chronic toxicity and the acute toxicity caused by disturbance of manure should not be ignored.

Spatiotemporal characteristics of NH3 and H2S concentrations

The daytime NH3 and H2S concentrations in dairy barns were higher than those during the night in the current study (Fig. 2). Our results are in line with the findings by Wu et al.28 regarding NH3 emissions from naturally ventilated barns in Denmark. In addition, the diel changes of NH3 and H2S concentrations near the floor were parallel to the diel change of the temperature inside the barn (Fig. 2). The NH3 formation and release are affected by the temperature29. The temperature affects the urease activity in the excrement and a higher temperature increases the urease activity, accelerating urea decomposition into NH3. Formation and release of H2S from manure are also expected to be affected by the temperature, since the decomposition of S-containing organic compounds in manure is enzyme-dependent30.

The concentrations of NH3 and H2S near the floor were higher than those measured at 1.5 m above the floor in the dairy barns. In addition, the concentrations of NH3 and H2S were the highest near the manure aisle among different sampling locations (Fig. 3). Both NH3 and H2S come from the decomposition of N and S containing substances in manure and urine. The airflow pattern within the barns diluted NH3 and H2S in the air and was also responsible for the lower NH3 and H2S concentrations at 1.5 m above the floor. The study by Saha et al.20 also confirmed that the NH3 concentration and its discharge rate in naturally ventilated barns were affected by wind speed. The height of 1.5 m could be considered the height of the breathing line for cows and humans. The reduced concentrations of NH3 and H2S at this level can reduce the negative effects of these gases on dairy cows and farmers.

N and S contents in feed and the concentrations of NH3 and H2S

Multivariate linear regression analyses showed that the concentrations of NH3 and H2S in the dairy barns were closely related to the contents of N and S in the feed, in addition to the significant influence by the temperature inside the barns. Concentrations of NH3 and H2S were significantly higher in lactating barns than those in non-lactating dairy barns. Lactating cows had a higher feed intake and their feed nutrient concentrations were much higher than non-lactating dairy cows. A significant correlation between the S content in the feed of dairy cows and the level of H2S in the air of the barn has been reported before25. Similarly, a higher level of dietary protein levels resulted in higher concentrations of total nitrogen in fresh manure and urine31. The decomposition of urea leads to the rapid rise of NH3 concentration in the barns.

Emission rates

Typically, emission estimates are calculated using emission factors (EF) and numbers of animals32. The available emission rates for NH3 and H2S in the literature mainly come from European and American countries, including Estonia18, Germany20,29, Denmark28, Switzerland33,34, Portugal35, and the United States36.

Quantification of emissions from naturally ventilated buildings has been a complicated and challenging task, as a result of difficult and inaccurate determination of airflow rates. Several methods have been developed, each with its own advantages and drawbacks37,38. Among them, the CO2 mass balance method and the pressure difference method have been used for naturally ventilated buildings for cattle. Carbon dioxide formed by animal respiration can be used as a natural tracer gas, assuming that CO2 can be mixed very well with the air inside the building. However, the molecular weight of CO2 is 44.01 and is higher than the average molecular weight of air (28.96), making CO2 accumulating near the floor surface and the CO2 balance method somewhat flawed. Additional drawback for the CO2 mass balance method is inaccurate estimation of the CO2 production due to variations by animals37. The ventilation rate throughout a naturally ventilated barn is dependent on both thermal buoyancy forces and wind pressure on the openings of the building. Thus, the wind pressure and temperature difference forces method calculates the ventilation rate through determination of wind speed and temperature inside the barn. The main drawbacks of this approach are the non-uniform distribution of the pressure differences and the velocity profile across the ventilation openings and through time, especially for barns with very large openings. This method tends to overestimate the emission rates38, which was also seen in the current study (Table 4). Therefore, while the results calculated from both methods are presented for the purpose of comparison, we prefer to use the results from the CO2 method.

The average NH3 emission rate was 30.6 g NH3/(AU·d), while the average H2S emission rate was 0.28 g H2S/(AU·d) for lactating cow barns. On the other hand, the average NH3 emission rate was 22.9 g NH3/(AU·d) and the average H2S emission rate was 0.24 g H2S/(AU·d) in non-lactating cow barn for this study, based on the CO2 balance method. The higher emission rates of NH3 and H2S for the lactating cow barns than those for the non-lactating cow barns may be related to the higher content of nitrogen and sulfur in the feed for lactating cows. As shown in Fig. 5, our emission rate for NH3 (26.75 g NH3/AU·d) was slightly higher than those reported for Estonia18, Sweden19, and the USA39. On the contrary, our number was slightly lower than those reported for the UK40, Portugal35, and Germany41. Interestingly, our NH3 emission rate was much lower than those previously estimated for Chinese dairy farms42,43. The average emission rate of H2S for all dairy barns was 0.26 g H2S/(AU·d), which is much higher than that reported by Maasikmets et al.18 (0.14 ± 0.08gH2S/(AU·d)) of the Estonia. Multiple factors such as the difference of measurement methods, feeding levels, environmental effects and barn structures could be responsible for different emission rates of different countries. The major difference of the emission rates of NH3 between the current study and the previous studies for China calls for more field studies.

Materials and Methods

Dairy farms and herd profile

The study was conducted from July 4 to August 21, 2017 inside and outside of 11 dairy barns in three farms in Henan province. Henan province is located in the central China, with east longitude 110°21′~116°39′ and north latitude 31°23′~36°22′. The farms are more than 1 km away from residential areas. The detailed description of these dairy barns is in Table 5. All 11 barns are naturally ventilated through open walls and a double-slope bell tower shaped roof (Fig. 4). Additionally, 32 axial fans and 64 sprinklers are installed beneath the ceiling in each barn (Fig. 4). The cooling system operates intermittently: the fans operate for 5 min and then sprinklers run for 1 min. The cow bedding is solid with rubber mattress or sandy soil. There are exercise areas outside the barns. Eleven barns housed a total of 1,450 heads of Holstein cows. Among them, 980 cows were lactating, with an average weight of 630 kg and an average daily milk production of approximately 27 kg. The cows were machine-milked three times daily at 4:00, 14:00 and 21:00. The remaining 470 cows were non-lactating, with an average weight of approximately 600 kg. All animals were fed three times daily at 8:30, 12:00 and 18:00 with total mixed rations. Manure was removed twice daily at 8:00 and 17:00 with a bulldozer. All experimental protocols used in this experiment were in accordance with those approved by the Northwest Agriculture and Forestry (A&F) University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol number NWAFAC1022) and the institutional safety procedures were followed.

Nitrogen and sulfur in feed and excretes

The dairy cows were fed a totally mixed ration (TMR). The average feed consumption was 44.5 kg/(AU·d) for lactating cows, while the average feed consumption was 41.5 kg/ (AU·d) for non-lactating cow. Fresh urine and fecal samples were collected three times daily (morning, noon and evening per day) for two days. The collected samples were stored at 4 °C before measurement on the same day. Nitrogen were determined by the Kjeldahl method. Sulfur were determined by the turbidimetric method44. The nitrogen and sulfur in feed and excreta are presented in Table 6.

Measurement of NH3 and H2S concentrations

NH3 and H2S concentrations were measured both inside and outside the barns. As shown in Figs 5 and 6 locations were sampled in each barn, including 2 manure areas, 2 cow bed locations and 1 feeding alley. Outside the dairy barns, sample locations included blank areas (upwind locations 20 m away from the barn), a manure storage area and a cow exercising area. Each location was sampled both near the floor and at 1.5 m above the floor. Near the floor is where NH3 and H2S gases are produced. The height at 1.5 m above the floor is approximately the breathing height for cows and dairy farmers. Gas samples were taken every two hours for 30 continuous minutes. The total sampling period was 48 h. The NH3 and H2S gases were collected using an integrated air sampler (2000C, Tuowei Instrument Ltd, Qingdao, China, flow range 0.1 L/min–1.0 L/min). A spectrophotometer (C752N754PC, Jinghua Instrument Ltd, Shanghai, China) was used for colorimetric analyses of NH3 and H2S concentrations. NH3 was measured using the Nessler’s reagent spectrophotometry method. NH3 in the air was absorbed using 0.05 mol/L dilute H2SO4. The generated NH4+ ions react with the Nessler reagent to form a yellow-brown complex. The absorbance of the complex proportional to the NH3 content was measured at a wavelength of 420 nm. The detection limit of NH3 was 0.01 mg/m3. Concentrations of NH3 were measured every 2 hours and calculated according to Eq. 3.

\({C}_{N{H}_{3}}\) or \({C}_{{H}_{2}S}\)——NH3 or H2S concentration, mg/m3;

A——the absorbance of the sample;

A0——the absorbance of the blank with the same sample preparation liquid;

a——calibration curve intercept

b——calibration curve slope;

Vs——the total volume of sample absorption solution, mL;

V0——the volume of analyzed fluid, mL;

Vnd——the standard volume of gas sample (101.325 kPa, 273 K), L;

D——dilution factor.

The H2S content was measured using the methylene blue spectrophotometric method45 with minor modifications. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 665 nm. The minimum detectable concentration was 0.001 mg/m3. Concentrations of H2S were measured every 2 hours and calculated according to Eq. 3.

Environmental parameters

Environmental parameters were measured in the same locations and heights as for measurement of NH3 and H2S. The temperature, relative humidity (RH), wind speed, atmospheric pressure, CO2 and total suspended particles (TSP) inside and outside each barn were also measured. The temperature and humidity were recorded every 2 hours on an automatic temperature and humidity recorder (LGR-WSD20, Rogue Instrument Ltd, Hangzhou, China). Wind speed, atmospheric pressure, CO2 and TSP (Total suspended particles) were measured using an anemometer (405-V1, Testo, Lenzkirch, Germany), a barometer (DYM3 Yipin Instrument Ltd, Shanghai, China), a portable CO2 detector (JSA8, Jiada Instrument Ltd, Shenzhen, China) and a dust detector (JC-1000, Jingcheng Instrument Ltd, Qingdao, China), respectively.

Calculation of ventilation rates

The ventilation rate is the rate at which air enters and leaves a building and is expressed in cubic meters per hour. The ventilation rate was calculated using two methods: CO2 balance method46,47, and the wind pressure and temperature difference forces method (WT method)41. The parameters required by the aforementioned methods were simultaneously measured in order to allow calculation of the ventilation rate at the same time, making comparison between the methods possible.

The emission rate of a gas was calculated using the following Eq. 4.

Et — emission rate of a gas (g/h);

QA — adjusted ventilation rate (m3/h);

Ci and Co —average concentrations (g/m3) of the gas inside and outside the building, respectively.

The weight of the cows and the production may differ from herd to herd. To make results comparable, the emission per animal unit (AU) was used in the modelling instead of emission per cow. The AU is equivalent to 500 kg animal mass47. The emission rate per AU can thus be stated as Eq. 5.

E — gas emission rate per animal unit (g/(AU·h))

Et — the emission rate of a gas (g/h)

N —the total number of cows housed inside the building

m — the average mass of a cow accommodated in the building (kg/cow).

Data analyses

Before statistical analysis, all data were checked and normalized if needed to satisfy the requirement of normality and homogeneity of variance. A mixed linear model was used to describe the effect of environmental and nutritional factors on NH3 or H2S concentrations as Eq. 6.

Eijk was the dependent variable (NH3 or H2S concentration); μ is the overall mean of the dependent variable; bi was the barn, i = 1 to11, bij was the measuring height, j = 1,2; β1, β2, and β3 was the coefficient of fixed effect; N∙Tin represented the interaction between the N content in the feed and indoor temperature Tin; eijk represents random errors. All other environmental and nutritional factors and their interactions were also considered during the initial stage and were removed from the model due to insignificant effects.

The influence of independent variables (the N content in the feed (Nf), N content in manure (Nm), N content in the urine (Nu), S content in the feed (Sf), S content of in manure (Sm), S content in urine (Su), indoor temperature (Tin), indoor wind speed W, CO2 and TSP concentrations) on NH3 and H2S concentrations inside the dairy barns (dependent variables) were first evaluated by calculating the Pearson’s correlation coefficient values. Then, the multi-collinearity among independent variables was examined by tolerance values and variance inflation factors. Finally, a multiple linear regression model was established by a stepwise procedure.

The fitting of the mixed linear model and the multiple linear regression method was performed using the SPSS 23.0 (IBM). Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with LSD multiple comparisons. The significance level was P < 0.05. Graphs were prepared using the Original Pro 8 software.

References

Alexandratos, N. & Bruinsma, J. World Agriculture Towards 2030/2050: The 2012 Revision. Rome, FAO, http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/esa/Global_persepctives/world_ag_2030_50_2012_rev.pdf (Accessed on 13 March 2018).

Herrero, M. & Thornton, P. K. Livestock and global change: Emerging issues for sustainable food systems. PNAS 110, 20878–20881, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1321844111 (2013).

Pelletier, N. & Tyedmers, P. Forecasting potential global environmental costs of livestock production 2000–2050. PNAS 107, 18371–18374, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1004659107 (2010).

Steinfeld, H. et al. Livestock’s Long Shadow: Environmental issues and options. Rome, FAO, http://agris.faoorg/agris-search/search.do?recordID=XF2006428907 (Accessed on 13 March 2018.

Feilberg, A., Hansen, M. J., Liu, D. & Nyord, T. Contribution of livestock H2S to total sulfur emissions in a region with intensive animal production. Nat. Commun. 8, 1069, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01016-2 (2017).

Velthof, G. L. et al. A model for inventory of ammonia emissions from agriculture in the Netherlands. Atmos. Environ. 46, 248–255, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.09.075 (2012).

Xu, P., Koloutsou-vakakis, S., Rood, M. J. & Luan, S. Projections of NH3 emissions from manure generated by livestock production in china to 2030 under six mitigation scenarios. Sci. Total. Environ. 607-608, 78–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.258 (2017).

FAO, http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QL, (Accessed on 13 March 2018).

Shen, F. et al. Air pollution characteristics and health risks in Henan Province, China. Environ. Res. 156, 625–634, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2017.04.026 (2017).

Dasarathy, S. et al. Ammonia toxicity: from head to toe? Metab. Brain. Dis. 32, 529–538, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-016-9938-3 (2017).

Moreno, L., Predicala, B. & Nemati, M. Laboratory, semi-pilot and room scale study of nitrite and molybdate mediated control of H2S emission from swine manure. Bioresource Technol. 101, 2141–2151, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2009.11.011 (2010).

Hooser, S. B., Alstine, W. V., Kiupel, M. & Sojka, J. Acute pit gas (hydrogen sulfide) poisoning in confinement cattle. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 12, 272–275, https://doi.org/10.1177/104063870001200315 (2000).

Beaver, R. L. & Field, W. E. Summary of documented fatalities in livestock manure storage and handling facilities 1975–2004. J. Agrome. 12, 3–23, https://doi.org/10.1300/J096v12n02_02 (2007).

Oesterhelweg, L. & Püschel, K. Death may come on like a stroke of lightening. Int. J. Legal. Med. 122, 101–107, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-007-0172-8 (2008).

Lewis, R. J. & Copley, G. B. Chronic low-level hydrogen sulfide exposure and potential effects on human health: a review of the epidemiological evidence. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 45, 93–123, https://doi.org/10.3109/10408444.2014.971943 (2014).

Pitts, J. N. & Finlayson-Pitots, B. J. Chemistry of the Upper and Lower Atmosphere. Academic Press, San Diego, https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-257060-5.x5000-x (2000).

Verma, S. et al. Modeling and analysis of aerosol processes in an interactive chemistry general circulation model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 112, D03207, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JD006077 (2007).

Maasikmets, M., Teinemaa, E., Kaasik, A. & Kimmel, V. Measurement and analysis of ammonia, hydrogen sulphide and odour emissions from the cattle farming in Estonia. Biosyst. Engin. 139, 48–59, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2015.08.002 (2015).

Ngwabie, N. M., Jeppsson, K. H., Gustafsson, G. & Nimmermark, S. Effects of animal activity and air temperature on methane and ammonia emissions from a naturally ventilated building for dairy cows. Atmos. Environ. 45, 6760–6768, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.08.027 (2011).

Saha, C. K. et al. The effect of external wind speed and direction on sampling point concentrations, air change rate and emissions from a naturally ventilated dairy building. Biosys. Engin. 114, 267–278, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2012.12.002 (2013).

Allen, R., Myles, L. & Heuer, M. W. Ambient ammonia in terrestrial ecosystems: a comparative study in the Tennessee Valley, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 409, 2768–2772, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.04.017 (2011).

Yang, Y. et al. Quantification of ammonia emissions from dairy and beef feedlots in the Jing-Jin-Ji district, China. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 232, 29–37, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2016.07.016 (2016).

Ngwabie, N. M., Jeppsson, K. H., Nimmermark, S., Swensson, C. & Gustafsson, G. Multi-location measurements of greenhouse gases and emission rates of methane and ammonia from a naturally-ventilated barn for dairy cows. Biosys. Engin. 103, 68–77, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2009.02.004 (2009).

Clark, P. C. & Mcquitty, J. B. Air quality in six alberta commercial free-stall dairy barns. Can. Agr. Eng. 29, 77–80 (1987).

Andriamanohiarisoamanana, F. J. et al. Effects of handling parameters on hydrogen sulfide emission from stored dairy manure. J. Environ. Manage. 154, 110–116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.02.003 (2015).

Dai, X. R. & Blanes-Vidal, V. Emissions of ammonia, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen sulfide from swine wastewater during and after acidification treatment: effect of pH, mixing and aeration. J. Environ. Manage. 115, 147–154, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.11.019 (2013).

Maebashi, K. et al. Toxicological analysis of 17 autopsy cases of hydrogen sulfide poisoning resulting from the inhalation of intentionally generated hydrogen sulfide gas. Forensic Sci. Int. 207, 91–95, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.09.008 (2011).

Wu, W., Zhang, G. & Kai, P. Ammonia and methane emissions from two naturally ventilated dairy cattle buildings and the influence of climatic factors on ammonia emissions. Atmos. Environ. 61, 232–243, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.07.050 (2012).

Saha, C. K. et al. Seasonal and diel variations of ammonia and methane emissions from a naturally ventilated dairy building and the associated factors influencing emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 468-469, 53–62, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.08.015 (2014).

Andriamanohiarisoamanana, F. J. et al. The seasonal effects of manure management and feeding strategies on hydrogen sulphide emissions from stored dairy manure. J. Mater Cycles Waste Manag. 19, 1253–1260, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-016-0519-7 (2016).

Petit, H. V., Ivan, M. & Mir, P. S. Effects of flaxseed on protein requirements and n excretion of dairy cows fed diets with two protein concentrations. J. Dairy Sci. 88, 1755–1764, https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72850-2 (2005).

USEPA. Compilation of Air Pollutant Emission Factors, https://www.epa.gov/air-emissions-factors-and-quantification/ap-42-compilation-air-emissions-factors (Accessed on13 March 2018).

Schrade, S. et al. Ammonia emissions and emission factors of naturally ventilated dairy housing with solid floors and an outdoor exercise area in Switzerland. Atmos. Environ. 47, 183–194, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.11.015 (2012).

Kupper, T., Bonjour, C. & Menzi, H. Evolution of farm and manure management and their influence on ammonia emissions from agriculture in Switzerland between 1990 and 2010. Atmos. Environ. 103, 215–221, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.12.024 (2015).

Pereira, J., Misselbrook, T. H., Chadwick, D. R., Coutinho, J. & Trindade, H. Ammonia emissions from naturally ventilated dairy cattle buildings and outdoor concrete yards in Portugal. Atmos. Environ. 44, 3413–3421, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.06.008 (2010).

Faulkner, W. B. & Shaw, B. W. Review of ammonia emission factors for united states animal agriculture. Atmos. Environ. 42, 6567–6574., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.04.021 (2008).

Ogink, N. W. M., Mosquera, J., Calvet, S. & Zhang, G. Methods for measuring gas emissions from naturally ventilated livestock buildings: Developments over the last decade and perspectives for improvement. Biosyst. Engin. 116, 297–308, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosys-temseng.2012.10.005 (2013).

Calvet, S. et al. Measuring gas emissions from livestock buildings: A review on uncertainty analysis and error sources. Biosyst. Engin. 116, 221–231, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosys-temseng.2012.11.004 (2013).

Mukhtar, S., Mutlu, A., Capareda, S. C. & Parnell, C. B. Seasonal and spatial variations of ammonia emissions from an open-lot dairy operation. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 58, 369–376, https://doi.org/10.3155/1047-3289.58.3.369 (2008).

Misselbrookm, T. H. et al. Key unknowns in estimating atmospheric emissions from UK land management. Atmos. Environ. 45, 1067–1074, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.11.014 (2011).

Samer, M. et al. Radioactive 85kr and CO2-balance for ventilation rate measurements and gaseous emissions quantification through naturally ventilated barns. Trans. ASAE. 54, 1137–1148, https://doi.org/10.13031/2013.37105 (2011).

Zhang, Y. et al. Agricultural ammonia emissions inventory and spatial distribution in the north china plain. Environ. Pollu. 158, 490–501, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2009.08.033 (2010).

Gao, Z., Ma, W., Zhu, G. & Roelcke, M. Estimating farm-gate ammonia emissions from major animal production systems in china. Atmos. Environ. 79, 20–28, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.06.025 (2013).

Iwata, J. & Nishikaze, O. New micro-turbidimetric method for determination of protein in cerebrospinal fluid and urine. Clin. Chem. 25, 1317–1319 (1979).

Fogo, J. K. & Popowsky, M. Spectrophotometric determination of hydrogen sulfide. Anal. Chem. 6, 732–734, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac60030a028 (1949).

CIGR. Working group report on: heat and moisture production at animal and house level. Danish Institute of Agricultural Sciences (DIAS), Horsens, Denmark (2002).

Samer, M. et al. Heat balance and tracer gas technique for airflow rates measurement and gaseous emissions quantification in naturally ventilated livestock buildings. Energ. Buildings. 43, 3718–3728, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2011.10.008 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China [2016YFD0500507]. We thank Luoxiong Zhou, Guanhua Fu, Zhuangzhuang Zhang, Shengyuan Zhang, and Qinliang Chen for their assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.F.S. carried out the whole experimental trial, and the paper writing. X.Q.S. and L.X. participated in the experimental design, and the paper writing. Y.L. participated in the sampling and chemical analysis. X.Z. made crucial contributions to the experimental design and modified the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, Z., Sun, X., Lu, Y. et al. Emissions of ammonia and hydrogen sulfide from typical dairy barns in central China and major factors influencing the emissions. Sci Rep 9, 13821 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50269-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50269-y

This article is cited by

-

Hazardous emission from thermal drying of municipal sludge and industrial sludge as well as associated odor pollution

Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management (2023)

-

Metagenomic analysis of microbial community structure and function in a improved biofilter with odorous gases

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.