Abstract

Candida tropicalis is a human pathogen associated with high mortality rates. We have reported a switching system in C. tropicalis consisting of five morphotypes – the parental, switch variant (crepe and rough), and revertant (crepe and rough) strains, which exhibited altered virulence in a Galleria mellonella model. Here, we evaluate whether switching events may alter host-pathogen interactions by comparing the attributes of the innate responses to the various states. All switched strains induced higher melanization in G. mellonella larvae than that induced by the parental strain. The galiomicin expression was higher in the larvae infected with the crepe and rough morphotypes than that in the larvae infected with the parental strain. Hemocytes preferentially phagocytosed crepe variant cells over parental cells in vitro. In contrast, the rough variant cells were less phagocytosed than the parental strain. The hemocyte density was decreased in the larvae infected with the crepe variant compared to that in the larvae infected with the parental strain. Interestingly, larvae infected with the revertant of crepe restored the hemocyte density levels that to those observed for larvae infected with the parental strain. Most of the switched strains were more resistant to hemocyte candidacidal activity than the parental strain. These results indicate that the switch states exhibit similarities as well as important differences during infection in a G. mellonella model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phenotypic switching is a strategy that allows microorganisms to undergo adaptation to environmental changes. In fungi, this event is random, reversible and defined as the emergence of colonies with altered morphology at rates higher than the somatic mutation rates1. Currently, the best characterized fungal phenotypic switch is the ‘white-opaque’ transition of the opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans2, where pleiotropic effects on virulence have been described3,4.

Candida tropicalis is a clinically relevant species representing the second or third etiological agent of candidemia, especially in tropical regions5,6,7. C. tropicalis is genetically similar to C. albicans and can also undergo an epigenetic switch between white and opaque phenotypic states8,9,10. Cells from the white parental colonies appear round and have a smooth cell surface, whereas cells from the opaque (darker-colored) colonies are elongated and exhibit a spotted cell surface8. The white-opaque switch in C. tropicalis regulates a cryptic program of sexual reproduction, where only cells in the opaque state undergo efficient mating8. The white-opaque transition is also associated with sexual biofilm formation in C. tropicalis, in which biofilms are formed exclusively by opaque cells10. In addition, similar to C. albicans, C. tropicalis makes use of a tristable switching system between the white, gray, and opaque cell types11. C. tropicalis gray cells exhibit an intermediate level of mating capability and virulence in a mouse infection model compared to that of white and opaque cell types11.

In addition to the white-opaque and white-gray-opaque phenotypic transitions, C. tropicalis can undergo multiple forms of phenotypic switching. Soll et al.12 demonstrated for the first time that C. tropicalis can undergo a high-frequency switch during the course of a prolonged Candida infection in an immunocompromised host. Our group has demonstrated the occurrence of distinct isolate-specific switching repertoires in clinical isolates of C. tropicalis13. The switched strains exhibited altered in vitro virulence traits, including morphogenesis, biofilm formation and hemolysis capability, which could potentially affect their survival within the host13. Further, we showed that phenotypic switching in C. tropicalis is associated with changes in virulence. A switch strain named the crepe variant exhibited higher cytotoxicity to FaDu cells and higher virulence in a Galleria mellonella infection model compared to those of its parental counterpart strain (unswitched strain)14. Currently, the ways that switching affects the pathogen interactions with the host and the role of switching in the pathogenesis of C. tropicalis are largely unexplored.

Larvae of the greater wax moth G. mellonella are a well-accepted model for the study of fungal pathogen-host interactions and serve as complementary hosts to conventional vertebrate animal models15,16. This invertebrate model exhibits several traits that make it a useful model for fungal pathogenesis studies. G. mellonella larvae can be reared at 37 °C. This characteristic allows microorganisms to be studied under the temperature conditions at which they are pathogenic to human hosts17. An additional advantage of G. mellonella is that its innate response is evolutionarily conserved in relation to mammals and possesses both cellular and humoral defenses15,18. The cellular immune response is mediated by phagocytic cells, termed hemocytes19, while the humoral defenses involve the production of effector molecules such as melanin and antimicrobial peptides20.

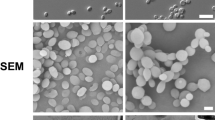

As the clinical isolates of C. tropicalis undertake phenotypic switching at high frequencies12,13 and because this event affects the virulence of C. tropicalis14, in the present study, we sought to evaluate whether the phenotypic switching may alter host-pathogen interactions using a G. mellonella model. To this end, we employed a switching system that was previously described by our group14 that comprises five colony phenotypes (morphotypes): the original phenotype (smooth colony dome); the two switch variants, exhibiting an irregular and structured dome surface (crepe and rough); and the switching revertants of the crepe and rough types (strains that switched back from the variants to the original phenotype), as illustrated in Fig. 1. The colonies of the strains presenting a smooth phenotype (original and revertant strains) consist entirely of budding yeast cells; in contrast, the cell morphologies in the colonies of the switched variants consist of budding yeast cells and of the filamentous forms (Fig. 1). In the present study, we evaluated several traits, including the melanization, expression of galiomicin and gallerymicin-encoding genes, phagocytosis, hemocyte density and the capacity of hemocytes to kill Candida cells. These findings could provide information on the insect immune response to the morphotypes of C. tropicalis and the role of switching on C. tropicalis pathogenesis.

Representative colonies of morphotypes of the phenotypic system 49.07 of C. tropicalis. (A) Smooth phenotype (parental strain and revertant of the crepe and rough types); (B) crepe phenotype (variant crepe); (C) rough phenotype (variant rough). Top line shows images of parental strain – clinical strain from tracheal secretion. Middle line shows images of crepe variant. Bottom line shows images of rough variant. Colonies phenotypes following 96 h incubation on YPD agar at 28 °C: (A1) parental strain; (B1) crepe variant and (C1) rough variant were photographed using a stereoscopic microscope (Nikon SMZ-745). Light microscopy of safranin-O cell staining of cells types in the colonies (blastoconidia and filamentous forms) (63×): (A2) parental smooth colony; (B2) crepe variant colony and (C2) rough variant colony. Scanning electron micrographs of cells types in the colonies: cells from parental smooth colony (A3); cells from crepe variant colony (B3) and cells from rough variant colony (C3). Scale bars = 50 µm.

Results

Switched strains of C. tropicalis promote increased melanization in Galleria mellonella

Previous work has established the suitability of the larvae of G. mellonella for detecting variations in the virulence of the switched strains of C. tropicalis, where a variant strain named crepe was more virulent than its original counterpart (parental strain), in contrast to a variant strain named rough that was less virulent than the parental strain14. In the present work, we aimed to evaluate the influence of phenotypic switching on larval humoral defense, particularly the production of melanin, which is a key step in the antimicrobial response of G. mellonella. We examined larvae melanization postinfection with the variants (crepe and rough) and their revertant (CR and RR) strains in comparison to the melanization of larvae that were infected with the parental strain (clinical isolate). This parameter can be monitored by measuring the OD at 405 nm of the hemolymph obtained from infected larvae.

In all of the larvae that were infected with the different strains, a typical dark color was observed due to the accumulation of melanin, in contrast with the nonmelanized larvae that had been injected with PBS (control), as illustrated in Fig. 2. Melanization was observed in the hemolymph of larvae that had been infected with all strains of the switching system (parental, switched strains and revertants). At 2-h postinfection, the larvae that had been infected with the switched strains showed the same extent of melanin production as that observed for the larvae that had been infected with the parental strain (Fig. 2A). At 24-h postinfection, both variants (crepe and rough) induced higher melanization in G. mellonella larvae than that in their parental counterpart (original strain) (p = 0.0001). Further, the revertant of crepe (CR) and the revertant of rough (RR) also induced higher melanization than the parental strain (Fig. 2B), despite their parental-like colony morphology. These data suggest that phenotypic switching in C. tropicalis generates strains that are differently recognized by G. mellonella larvae.

Melanization in Galleria mellonella larvae post-infection 2 h (A) and 24 h (B) with 5 × 105 cell per larvae of morphotypes of the 49.07 phenotypic switching system of Candida tropicalis (parental strain, crepe variant, rough variant, revertant of crepe [CR] and revertant of rough [RR]). Melanization of the switched morphotypes relative to the melanization of the parental morphotype. Not melanized: larvae injected with PBS (control). Melanized: a typical dark color due to accumulation of melanin after larvae infection.

Phenotypic switching in C. tropicalis causes the altered expression of genes encoding antimicrobial peptides by G. mellonella larvae

Antimicrobial peptides, or host-defense peptides, play a major role in innate immunity, showing broad-spectrum microbicidal activity. We analyzed the expression of the galiomicin and gallerymicin peptide-encoding genes, which are associated with the immune response of G. mellonella, to evaluate the insect humoral response postinfection with the switched strains of C. tropicalis. Larvae were infected with the unswitched (parental) and switched strains, and RNA was extracted at 4-h postinfection. Transcriptional activation is represented by the fold change of the expression of the galiomicin and gallerymicin genes in the parental strain-infected G. mellonella and the switched strains-infected G. mellonella relative to that in the PBS-injected control larvae and was normalized using the housekeeping gene β-actin.

Analysis by real-time quantitative PCR showed that the levels of galiomicin were higher in insects infected with the crepe variant (p = 0.0023) and rough variant (p = 0.0030) than those in insects infected with the parental strain (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, both revertants (CR and RR) exhibited lower galiomicin expression than that in their variant counterparts, where the revertant of crepe exhibited galiomicin expression levels that were restored to the levels that were observed in response to the parental strain.

Relative gene expression of peptides galiomicin (A) and gallerymicin (B) 4-h postinfection with 5 × 105 cell per larvae of all morphotypes of Candida tropicalis (parental strain, crepe variant, rough variant, revertant of crepe [CR] and revertant of rough [RR]). Data were normalized with the β-actin gene and relativized with the expression of larvae inoculated with PBS solution.

The amount of gallerymicin mRNA at 4-h postinfection did not differ between the insects infected with the crepe variant and those infected with the parental strain. Only larvae infected with the rough variant showed a higher expression level of gallerymicin compared to that in the larvae infected with the parental strain (p = 0.0384) (Fig. 3B). The RR exhibited lower gallerymicin expression compared to its variant counterpart and its parental strains.

Switched strains are phagocytosed by G. mellonella hemocytes at distinct rates

The fluctuation in the phagocytosis rate has been related to the ability of microorganisms to kill larvae. We examined whether cells of the switched strains differ in the extent to which they are phagocytosed by G. mellonella hemocytes compared to that observed for the parental strain.

All morphotypes (parental, switched strains and revertants) were phagocytosed by G. mellonella hemocytes after 2 h of Candida cell/hemocyte cocultivation (Fig. 4A). The crepe variant was more effectively phagocytosed by G. mellonella hemocytes than the parental strain (p = 0.0002), whereas the rough variant was less phagocytosed (p = 0.0001) than the parental strain, indicating that the strains are differently recognized by the immune components. The amount of phagocytosis of the crepe revertant was also significantly higher (p = 0.0002) than the amount of phagocytosis observed with the parental strain, while the revertant of rough showed the same extent of phagocytosis as the parental strain (Fig. 4A), and thus, the reversion restored the phagocytic susceptibility of the original clinical strain.

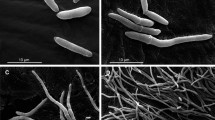

Percentage of phagocytosis of Candida tropicalis morphotypes by Galleria mellonella hemocytes co-cultured in a ratio of 5:1 (Candida morphotypes cells/hemocyte cells) for 2 h (A). Morphotypes: parental strain, crepe variant, revertant of crepe (CR), rough variant and revertant of rough (RR). Scanning electron microscopy photomicrographs showing interactions of C. tropicalis parental strain with G. mellonella hemocytes after 2 h of infection (B1, B2). Scale bars = 10 µm.

The electron micrograph shows the G. mellonella hemocyte-Candida cell interactions (Fig. 4B1, B2). Hemocytes were able to engulf the cells of all of the strains of the switching system (data not shown). The Candida cells were surrounded by hemocyte membrane projections (Fig. 4B1) and were internalized by hemocyte cells (Fig. 4B2).

Infection with switched C. tropicalis strains leads to alterations in the density of circulating hemocytes

Hemocytes are important to the larva’s cellular defense against fungi since they act as phagocytic cells. Thus, we aimed to examine whether the switched strains had any effect on the hemocyte density. The majority of the strains induced a decrease in the hemocytes present in the hemolymph of G. mellonella compared with that of the control (PBS) (Fig. 5). At 4-hours postinfection, no differences in the hemocyte density were observed when the larvae were infected with the switched strains (variants and revertants) compared to that observed for infections with the parental strain (Fig. 5A). Differences in the hemocyte density were observed only between larvae infected with the rough and crepe variant strains. At a longer infection period (24 h), the hemocyte population was significantly lower in the larvae infected with the crepe variant strain than in those infected with the parental strain (p = 0.0003). For the larvae infected with all the remaining switched strains (crepe revertant, rough variant and rough revertant), no differences in the hemocyte density were observed compared to that in the parental strain (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, the larvae infected with the CR showed higher hemocyte density (p = 0.0002) compared to the larvae infected with its variant counterpart, restoring the levels to those observed for larvae infected with the parental strain (Fig. 5B).

Capability to survive in the presence of G. mellonella hemocytes in vitro varies among the switched phenotypes

To determine the candidacidal activity of hemocytes against the distinct morphotypes, hemocytes were extracted from larvae and coincubated in vitro with the morphotype cells. Killing was determined by colony forming unit (CFU) counts 4-h after coincubation. As shown in Fig. 6, the cell viability of the crepe and rough switched variants was higher than the cell viability of their parental counterpart strain. The cell viability of the crepe revertant was also significantly higher (p = 0.0001) than that of the parental strain, while the revertant of rough strain showed a significantly lower viability than that of the parental strain (p = 0.0385) (Fig. 6). This result indicates that larval immune cells possess candidacidal activity and that the resistance of the switched strains to G. mellonella hemocytes is variable.

Colony forming units (CFU) counts 4 h after in vitro co-incubation of hemocytes (1 × 105) and C. tropicalis morphotypes cells (5 × 105 cells). Morphotypes: parental strain, crepe variant, revertant of crepe (CR), rough variant and revertant of rough (RR). Candidacidal activity was determined by plating yeast cell suspensions onto YPD agar plates. Plates were incubated for 96 h and the resulting number of colonies enumerated (CFU/mL).

Discussion

Candida species are common human fungal pathogens that cause a wide range of clinical diseases. The increase in the isolation of C. tropicalis in cases of both superficial and systemic infections worldwide makes it one of the most important Candida species. In some settings, bloodstream infections due to C. tropicalis have been associated with higher mortality than infections with other Candida species21,22.

The G. mellonella infection model has recently been shown to be a suitable model for analyzing fungal virulence factors. For instance, differences in virulence between the phenotypic states of C. tropicalis were reported using this infection model14. Since differences in virulence may be due, at least in part, to differential interactions with the host immune components, we examined some of the humoral and cellular immune responses of G. mellonella that were challenged with the morphotypes of the switching system 49.07 (Fig. 1). An understanding of these interactions is important for proposing new strategies to eliminate invasive pathogens and to prevent host death.

During infection experiments, colonies phenotypes of recovered cells from G. mellonella larvae were checked and their frequencies verified by CFU counting. Cells of each morphotype (parental and switched strains) exhibited their original colony phenotype at same rates to that previously described for the 49.07 system where on average, reversibility occurred at a frequency of 1%13,14. Considering that G. mellonella humoral immune response comprises melanin, which plays a crucial role in defense reactions23, we evaluated the production of melanin by G. mellonella larvae that were challenged with the distinct morphotypes. The high melanin production observed in larvae infected with the switched phenotypes (Fig. 2) indicates that phenotypic switching generates strains that alter the larval humoral response. The increase of melanization in response to the switched strains may be due to the differential activation of the enzyme phenoloxidase, which is involved in the pathway leading to the formation of melanin24. Melanization reaction and the prophenoloxidase (inactive form of phenoloxidase) system are closely related in G. mellonella25. This activating system is one of the main immune responses in invertebrates where recognition of cell surface molecules by pattern recognition proteins triggers the prophenoloxidase activation cascade. The activated phenoloxidase oxidizes phenols to quinones, which subsequently polymerize non-enzymatically to melanin26. It has been recently showed that G. mellonella larvae infected with C. albicans, a closely related species to C. tropicalis, exhibited a significant increase in the expression of prophenoloxidase and phenoloxidase-activating proteinase encoding genes27. Considering that the phenoloxidase cascade and resulting melanization of G. mellonella larvae occurs during Candida infections and that this response has been associated with cell wall β-glucans28, the increased melanization of larvae challenged with switched strains of the C. tropicalis 49.07 system suggests that switch states may exhibit altered arrangements of the cell wall components.

We further evaluated the alterations in the humoral immune response by examining the expression of antifungal peptide-encoding genes. Using RT-PCR, we evaluated the change in the expression of the gene encoding galiomicin, a defensin identified in G. mellonella, and gallerymicin, a cysteine-rich defensin-like antifungal peptide. Our experiments demonstrate that both genes were highly expressed in larvae infected with the rough variant compared to the expression observed in larvae infected with the unswitched parental strain, and the difference was more pronounced for the galiomicin-encoding gene than that for the gallerymicin-encoding gene (Fig. 3A). This is consistent with the reduced capacity of the rough variant to kill G. mellonella larvae compared to that of the parental strain14. It has been demonstrated that thermal or physical stress can lead to the increased expression of galiomicin, and that this can be associated with a decreased susceptibility of G. mellonella larvae to infection by C. albicans29,30. In contrast, the crepe variant that exhibited the highest virulence against G. mellonella larvae among all of the morphotypes of the 49.07 system, including the parental strain14, also induced higher expression of galiomicin than that of the parental strain. Altogether, the data suggest that the switched variants of C. tropicalis can transiently induce the expression of antifungal peptides and that the role of galiomicin during infection with distinct switched strains may be variable, demonstrating that pathogenicity is a multivariable and complex process. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report in the literature that analyzes the antimicrobial peptide expression in G. mellonella that were challenged with C. tropicalis morphotypes that arose from a switching event.

A phagocytosis assay showed that hemocytes phagocytosed C. tropicalis cells after 2 h of in vitro coincubation. Further, our data revealed that the switched strains interact differentially with hemocytes (Fig. 4). The cells of the crepe variant and its switched revertant strain (CR) were preferentially phagocytosed by G. mellonella hemocytes compared to the cells of the parental strain; these data did not correlate with the effectiveness of killing the pathogen since the crepe variant was more virulent to G. mellonella larvae than the parental strain, as described previously14. For Candida species, hyphae and pseudohyphae contribute to virulence, promoting the evasion of phagocytosis. Mesa-Arango et al.31 described the presence of the pseudohyphae of C. tropicalis inside G. mellonella hemocytes. We demonstrated the capability of the crepe variant to develop in vitro filamentous forms to a greater extent than that of the parental strain13. Pseudohyphae formation could lead to the death of the hemocyte population. In contrast, the rough variant cells were less efficiently phagocytosed by hemocytes than the parental cells and the cells of the crepe variant, suggesting that the switching event in C. tropicalis may generate strains with a better escape mechanism from phagocytosis. Differences in phagocytosis among the distinct morphotypes (parental and switched strains) indicate that the strains are differently recognized by the G. mellonella immune components. Further, we showed that hemocytes can internalize a large number of C. tropicalis cells after 2 h of coincubation (Fig. 4B2). Studies are in progress to determine whether the switch state affects the composition or the rearrangement of specific components of the C. tropicalis cell wall, leading to altered recognition by hemocytes. As previous mentioned, it has been demonstrated that β-glucans in the yeast cell wall can activate some of the G. mellonella immune responses28,32.

Changes in the hemocyte density are another important factor to be examined in the immune response of G. mellonella larvae when studying fungal virulence33. A reduction in the number of hemocytes in the hemolymph has been reported in G. mellonella after infection with C. tropicalis31, so to further examine the properties of the switched strains that may impact host-pathogen interactions, we compared the hemocyte density of the larvae infected with the switched strains and parental strain. We observed the lowest numbers of hemocytes after 24 h of infection with the crepe variant among those associated with infections with the parental strain and with the other switched strains, possibly providing an explanation for the shorter survival with the crepe variant strain, as described previously14. A relationship between the ability of highly pathogenic yeast isolates to kill G. mellonella larvae and a reduction in the hemocyte density has been described34. We subsequently showed that the crepe variant and its revertant were more resistant to hemocytes than the parental strain, as revealed by CFU counting postincubation with hemocytes in vitro (Fig. 6). These data are in accordance with an in vivo assay in which larvae infected with these two strains exhibited a higher fungal burden than that observed for infections with the parental strain14. The rough variant was also more resistant to hemocytes than the parental strain, unlike its revertant strain, which exhibited the lowest resistance to hemocytes, suggesting a variable candidacidal ability for targeting the switched cells. Overall, the highly virulent crepe variant exhibited decreased hemocyte counts and increased resistance to hemocyte candidacidal activity compared to those of its parental strain counterpart. Interestingly, the CR strain, which arose by reverting from the crepe variant and thus exhibited smooth parental colony morphology, showed the same levels of hemocyte counts and virulence against G. mellonella, as well as the ability to induce galiomicin expression, as the parental strain (clinical isolate), revealing that some attributes of the host response, but not all, are restored following the switching reversion event in the pathogen. It is currently unknown the molecular mechanisms mediating phenotypic switching in C. tropicalis 49.07. Considering that transcriptional regulators form a complex regulatory network in Candida switching35,36,37, it is tempting to imagine that although parental and revertant strains of the 49.07 system show similar colony morphology, they exhibit distinct gene expression profiles. The mechanism responsible for the differences in host-pathogen interactions observed for the different colony types is currently not understood. A characterization of the cell wall of switched morphotypes could provide insights into the differential interactions with the host immune components observed for the variants and revertants strains in C. tropicalis. Currently, we still have much to learn about the role of switching in the pathogenesis of C. tropicalis.

In conclusion, in the present study, we found that phenotypic switching affected C. tropicalis virulence, at least in part, by altering the host-pathogen interactions in the G. mellonella infection model. The results indicate that phenotypic switching in C. tropicalis may generate strains that are differently recognized by the G. mellonella immune components, as well as generating strains that are more resistant to hemocyte candidacidal activity. These data may have the potential to further our understanding of C. tropicalis pathogenesis.

Methods

Microbial strains and culture conditions

Morphotypes (original phenotype-parental, crepe variant, crepe revertant, rough variant and rough revertant) of the switching phenotypic system 49.07 of C. tropicalis used in this study were stored as frozen stocks with 20% glycerol at −80 °C and subcultured on YPD agar plates (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% dextrose) at 28 °C. Morphotypes were routinely grown in YPD liquid medium at 28 °C in a shaking incubator and plated on YPD agar plates at 28 °C for 96 hours.

Fungal inocula preparation

Morphotypes were grown on YPD agar at 28 °C for 96 h. Colony cells were collected and resuspended in PBS. Yeast cells were counted using a hemocytometer, and the cell density was adjusted to 5 × 107 cells/ml.

Galleria mellonella rearing and larvae manipulation

G. mellonella larvae in the final stage without color alterations and with adequate weights (240–300 mg) were selected. The insect proleg regions were cleaned with 70% ethanol before the experiments. Each infection group and control group contained 10 randomly chosen larvae of the appropriate weight. Using a syringe (Hamilton, USA), 10 µl of inoculums with all morphotypes was injected into the hemocell through the last left proleg of the larvae, and the control group received only a PBS inoculum. The insects were maintained at 37 °C for 1, 2, 4 and 24 h under protection from light for further analysis. Each experiment was repeated at least 3 times.

Hemolymph collection

The in vitro experiments required hemolymph collection. To collect the hemolymph, the larvae were selected according to the following criteria: last instar, weighing 240–300 mg, and presenting with clear, uniform color without dark spots or grayish marks. To collect the hemolymph, we held the larva in its ventral position, punctured one of the central prolegs and collected the hemolymph. Adipose tissue and any liquid of a dark color were discarded. The collected hemolymph of ten larvae was transferred to a microtube containing 900 μL of IPS (insect physiological saline: 150 mM sodium chloride (Promega, USA), 5 mM potassium chloride (Promega), 10 mM Tris HCl (Promega) pH 6.9, 10 mM EDTA (Promega) and 30 mM sodium citrate (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) plus 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide (Sigma-Aldrich) (anticoagulant). Tubes were placed on ice, and sample collection was carried out immediately to avoid cell melanization. After centrifugation at 2000 rpm and at 4 °C for 5 min, the supernatant was discarded, cells were washed with 500 μl of cold IPS and the contents of two tubes (or several, depending on the number of assays) were pooled together in a new tube. A second centrifugation was performed under the same conditions. The supernatant was again discarded, and the cells were resuspended in 1000 μl IPS. The number of cells was determined with a Neubauer chamber.

Quantification of melanization

Melanization assays were performed according to Maurer et al.38, with modifications. Ten larvae per group were infected with the phenotypic strains and incubated at 37 °C. Hemolymph was collected at 2-h and 24-h postinfection and diluted 1:10 in IPS buffer supplemented with N-ethylmaleimide to prevent further melanization. A total of 100 µl of each sample was placed in 96-well microdilution plates, and an optical density (405 nm) reading was performed to quantify the melanization. The optical density values of hemolymph from the infected larvae were normalized to that of the control larvae (PBS inoculum). All experiments were performed in triplicate, as described above.

RNA extraction and gene expression analysis (RT-qPCR)

Larvae were inoculated as described above. Three replicate samples were collected at 4-h postinfection, and each of the triplicate samples comprised at least three whole larvae. Larvae from each experimental group were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground to a powder by mortar and pestle in TRIzol (Invitrogen, United Kingdom). The samples were further homogenized, and RNA was extracted and purified using a RNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was quantified and the quality assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific, Loughborough, United Kingdom). cDNA was synthesized from 200 ng of extracted RNA using an RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, EUA) in a GeneAmp® PCR (Eppendorf, Gradiente Mastercycler) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Primers used for quantitative PCR (qPCR) were as follows: galiomicin forward, 5′-CCTCTGATTGCAATGCTGAGTG-3′; galiomicin reverse, 5′-GCTGCCAAGTTAGTCAACAGG-3′; gallerymicin forward, 5′-GAAGATCGCTTTCATAGTCGC-3′; gallerymicin reverse, 5′-TACTCCTGCAGTTAGCAATGC-3′; β-actin forward, 5′-GGGACGATATGGAGAAGATCTG-3′; and β-actin reverse, 5′-CACGCTCTGTGAGGATCTTC-3′, as described elsewhere39.

The cycling conditions consisted of 2 min at 50 °C, 10 min at 95 °C, and 40 cycles of 15 s at 51 °C and 60 s at 60 °C. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate using a StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems®). The reactions were performed using Platinum® SYBR® Green qPCR Supermix-UDG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with a final volume of 20 μl. Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−(Δ-ΔCt) method.

Determination of hemocyte density

G. mellonella larvae (n = 10) were infected and treated as described above. After the infection period (4 and 24 h), hemolymph samples from 3 larvae of each group were collected in IPS supplemented with 10 mM of N-ethylmaleimide to prevent melanization and coagulation. The hemolymph was diluted 1:10, and the hemocyte density was estimated by using a hemocytometer under a light microscope. As a control, the samples were compared with those from PBS-injected larvae, and the results are expressed as a number of hemocytes/ml of hemolymph. Experiments were repeated at least 4 times.

Phagocytosis assay

To study the phenotypic switching effect on the phagocytic capacity of the hemocytes, 13-mm round coverslips that were treated with acetic acid were placed in a 24-well plate. Each well was filled with a volume corresponding to 1 × 105 hemocytes and was brought to a total volume of 1000 μl with RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, USA) plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco®, Brazil). The plates were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2 to allow cell adherence. Then, nonadherent hemocytes were removed by washing with RPMI 1640 medium at room temperature, and the adhered cells were coincubated with each morphotypic strain at a 1:5 ratio. Phagocytosis was allowed to occur for 2 h; samples were then washed to remove the nonadherent yeast. In sequence, samples were fixed with 1 ml cold methanol (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 20 min. Then, cells were stained with May-Grünwald (Laborclin, Brazil) for 15 min, washed with Sorenson’s buffer (0.133 M Na2HPO4 and 0.133 M KH2PO4) and immersed in Giemsa dye (Laborclin, Brazil) for 15 min. Finally, the coverslips were washed again with Sorenson’s buffer, air dried, and mounted on glass slides. Under an optical microscope (1000 times magnification), cells from 20 fields were analyzed and quantified according to the number hemocytes containing internalized yeast cells.

Phagocytic assay for microscopic analysis

A phagocytic assay for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis was conducted as described by Tomiotto-Pellissier et al.40, with modifications. Round coverslips (13 mm) treated with poly-L-lysine (Sigma Aldrich, USA) were placed in a 24-well plate. Each well was filled with a volume corresponding to 5 × 105 hemocytes and was adjusted to 1000 μl with RPMI 1640 medium plus 10% FBS. The plates were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2 to allow cell adherence. Then, nonadherent hemocytes were removed by washing with RPMI 1640 medium at room temperature. Adhered cells were infected with each morphotypic strain at a ratio of 1:2. Phagocytosis was allowed to occur for 2 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in 1 ml RPMI 1640 medium plus 10% FBS. Next, each coverslip was washed with IPS and fixed by immersion in 1 ml of fixative [2% glutaraldehyde (Sigma Aldrich, USA) in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (Sigma Aldrich, USA), pH 7.2] for 24 h. After this incubation, the samples were postfixed for 1 h in 1% OsO4 (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) diluted in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2. The fixed material was dehydrated in an ethanol gradient (30, 40, 50, 70, 80, 90 and 100°GL), and the samples were dried to the critical point with CO2 (BALTEC CPD 030 Critical Point Dryer), while placed on an aluminum holder. Coverslips were covered with tape for partial cell surface removal, and then the samples were coated with gold (BALTEC SDC 050 Sputter Coater) and analyzed by SEM (model Quanta 200, FEI, Netherlands).

Determination of the candidacidal activity of hemocytes

The capacity of hemocytes to kill Candida cells was determined with the colony forming unit (CFU) counts 4-h after coincubation. Hemocytes were extracted from larvae and incubated at a density of 1 × 105 hemocytes in 1 ml RPMI 1640 medium at 37 °C. C. tropicalis morphotypes (5 × 105 cells) were added, and killing was measured by diluting and plating yeast cell suspensions onto YPD agar plates. The plates were incubated for 96 h, and the resulting number of colonies was counted. The results were calculated from three experiments, with colony counts performed in triplicate for each sample.

Statistical analysis

Three independent experiments were performed in triplicate for all experiments. All data were previously submitted to the F test and the Shapiro-Wilk test for analysis of variance and normality test, respectively. Comparison between the groups were done by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analysis were performed by GraphPad Prism 5 statistical software (GraphPad Software, Inc., USA, 500.288). Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

References

Soll, D. R. High-frequency switching in Candida albicans. Clin Microbiol Rev 5, 183–203 (1992).

Slutsky, B. et al. “White-opaque transition”: a second high-frequency switching system in Candida albicans. J Bacteriol 169, 189–197 (1987).

Kvaal, C., Srikantha, T. & Soll, D. R. Misexpression of the white-phase-specific gene WH11 in the opaque phase of Candida albicans affects switching and virulence. Infect Immun 65, 4469–4475 (1997).

Kvaal, C. et al. Misexpression of the opaque-phase-specific gene PEP1 (SAP1) in the white phase of Candida albicans confers increased virulence in a mouse model of cutaneous infection. Infect Immun 67, 6652–6662 (1999).

Costa, V. G., Quesada, R. M. B., Stipp-Abe, A. T., Furlaneto-Maia, L. & Furlaneto, M. C. Nosocomial bloodstream Candida infections in a tertiary-care hospital in South Brazil: a 4-year survey. Mycopathologia 178, 243–250 (2014).

Rodriguez, L. et al. A multi-centric study of Candida bloodstream infection in Lima-Callao, Peru: species distribution, antifungal resistance and clinical outcomes. PLos One 12, e0175172 (2017).

Matta, D. A., Souza, A. C. R. & Colombo, A. L. Revisiting species distribution and antifungal susceptibility of Candida bloodstream isolates from Latin American medical centers. J Fungi 3, 24 (2017).

Porman, A. M., Alby, K., Hirakawa, M. P. & Bennett, R. J. Discovery of a phenotypic switch regulating sexual mating in the opportunistic fungal pathogen Candida tropicalis. Proc Nat Acad Sci 108, 2158–2163 (2011).

Xie, J. et al. N-Acetylglucosamine induces white-to-opaque switching and mating in Candida tropicalis, providing new insights into adaptation and fungal sexual evolution. Eukaryot Cell 11, 773–782 (2012).

Jones, S. K. Jr, Hirakawa, M. P. & Bennett, R. J. Sexual biofilm formation in Candida tropicalis opaque cells. Mol Microbiol 92, 383–398 (2014).

Zhang, Y. et al. The gray phenotype and tristable phenotypic transitions in the human fungal pathogen Candida tropicalis. Fungal Genet Biol 93, 10–16 (2016).

Soll, D. R. et al. Multiple Candida strains in the course of a single systemic. J Clin Microbiol 26, 1448–1459 (1988).

Moralez, A. T., França, E. J., Furlaneto-Maia, L., Quesada, R. M. & Furlaneto, M. C. Phenotypic switching in Candida tropicalis: association with modification of putative virulence attributes and antifungal drug sensitivity. Med Mycol 52, 106–114 (2014).

Moralez, A. T. P. et al. Phenotypic switching of Candida tropicalis is associated with cell damage in epithelial cells and virulence in Galleria mellonella model. Virulence 7, 379–386 (2016).

Lionakis, M. S. Drosophila and Galleria insect model hosts: new tools for the study of fungal virulence, pharmacology and immunology. Virulence 2, 521–527 (2011).

Champion, O. L., Wagley, S. & Titball, R. W. Galleria mellonella as a model host for microbiological and toxin research. Virulence 7, 840–845 (2016).

Fuchs, B. B., O’Brien, E., El Khoury, J. B. & Mylonakis, E. Methods for using Galleria mellonella as a model host to study fungal pathogenesis. Virulence 1, 475–482 (2010).

Kavanagh, K. & Reeves, E. P. Exploiting the potential of insects for in vivo pathogenicity testing of microbial pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev 28, 101–112 (2004).

Lavine, M. D. & Strand, M. R. Insect haemocytes and their role in immunity. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 32, 1295–1309 (2002).

Strand, M. R. Insect Hemocytes and Their Role in Immunity. In Insect Immunology. (ed. Beckage, N. E.) 25–47. Academic Press/Elsevier, San Diego (2008).

Kontoyiannis, D. P. et al. Risk factors for Candida tropicalis fungemia in patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis 33, 1676–1681 (2001).

Colombo, A. L. et al. Prospective observational study of candidemia in Sao Paulo, Brazil: incidence rate, epidemiology, and predictors of mortality. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 28, 570–576 (2007).

Wand, M. E., McCowen, J. W., Nugent, P. G. & Sutton, J. M. Complex interactions of Klebsiella pneumoniae with the host immune system in a Galleria mellonella infection model. J Med Microbiol 62, 1790–1798 (2013).

Kopacek, P., Weise, C. & Gotz, P. The prophenoloxidase from the wax moth Galleria mellonella: Purification and characterization of the proenzyme. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 25, 1081–1091 (1995).

Wojda, I. Immunity of the greater wax moth Galleria mellonella. Insect Sci 24, 342–357 (2017).

Kanost, M. R. & Gorman, M. J. Phenoloxidases in insect immunity in Insect Immunology, (ed. Beckage, N. E.) 69–96 (Elsevier San Diego, 2008).

Sheehan, G. & Kavanagh, K. Analysis of the early cellular and humoral responses of Galleria mellonella larvae to infection by Candida albicans. Virulence 9, 163–172 (2018).

Rueda, C., Cuenca-Estrella, M. & Zaragoza, O. Paradoxical growth of Candida albicans in the presence of caspofungin is associated with multiple cell wall rearrangements and decreased virulence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58, 1071–1083 (2014).

Mowlds, P. & Kavanagh, K. Effect of pre-incubation temperature on susceptibility of Galleria mellonella larvae to infection by Candida albicans. Mycopathologia 165, 5–12 (2008).

Mowlds, P., Barron, A. & Kavanagh, K. Physical stress primes the immune response of Galleria mellonella larvae to infection by Candida albicans. Microbes Infect 10, 628–634 (2008).

Mesa-Arango, A. C. et al. The non-mammalian host Galleria mellonella can be used to study the virulence of the fungal pathogen Candida tropicalis and the efficacy of antifungal drugs during infection by this pathogenic yeast. Med Mycol 51, 461–472 (2013).

Mowlds, P., Coates, C., Renwick, J. & Kavanagh, K. Dose-dependent cellular and humoral responses in Galleria mellonella larvae following beta-glucan inoculation. Microbes Infect 12, 146–153 (2010).

Scorzoni, L. et al. Comparison of virulence between Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Paracoccidioides lutzii using Galleria mellonella as a host model. Virulence 6, 766–776 (2015).

Bergin, D., Brennan, M. & Kavanagh, K. Fluctuations in haemocyte density and microbial load may be used as indicators of fungal pathogenicity in larvae of Galleria mellonella. Microbes Infect 5, 1389–1395 (2003).

Porman, A. M., Hirakawa, M. P., Jones, S. K., Wang, N. & Bennett, R. J. MTL-independent phenotypic switching in Candida tropicalis and a dual role for Wor1 in regulating switching and filamentation. PLos Genet 9, e1003369 (2013).

Lohse, M. B. et al. Systematic genetic screen for transcriptional regulators of the Candida albicans white-opaque switch. Genetics 203, 1679–1692 (2016).

Yue, H. et al. Discovery of the gray phenotype and white-gray-opaque tristable phenotypic transitions in Candida dubliniensis. Virulence 7, 230–242 (2016).

Maurer, E. et al. Galleria mellonella as a host model to study Aspergillus terreus virulence and amphotericin B resistance. Virulence 6, 591–598 (2015).

Rajendran, R. et al. Acetylcholine protects against Candida albicans infection by inhibiting biofilm formation and promoting hemocyte function in a Galleria mellonella infection model. Eukaryot Cell 14, 834–844 (2015).

Tomiotto-Pellissier, F. et al. Galleria mellonella hemocytes: A novel phagocytic assay for Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis. J Microbiol Methods 131, 45–50 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Fundação Araucária-Paraná-Brazil grant 001/2017. This study was financed by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001, and Universidade Estadual de Londrina, PROPPG, Escritório de Apoio ao Pesquisador. MC Furlaneto is grateful to CNPq for the PQ fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C.F., L.F.-M. and H.F.P. conceived the experiments; H.F.P., A.T.P.M. and A.O.G.J. performed the experiments; H.F.P. and F.G.B. participated in data analysis of RT-qPCR; M.C.F., R.S.C.A. and L.A.P. participated in data analysis of phagocytic experiments. M.C.F., L.F.-M. and H.F.P. prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Perini, H.F., Moralez, A.T.P., Almeida, R.S.C. et al. Phenotypic switching in Candida tropicalis alters host-pathogen interactions in a Galleria mellonella infection model. Sci Rep 9, 12555 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49080-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49080-6

This article is cited by

-

Streptococcus mutans supernatant affects the virulence of Candida albicans

Brazilian Journal of Microbiology (2024)

-

Deciphering Colonies of Phenotypic Switching-Derived Morphotypes of the Pathogenic Yeast Candida tropicalis

Mycopathologia (2022)

-

Changes in Adhesion of Candida tropicalis Clinical Isolates Exhibiting Switch Phenotypes to Polystyrene and HeLa Cells

Mycopathologia (2021)

-

Pathophysiological effects of Klebsiella pneumoniae infection on Galleria mellonella as an invertebrate model organism

Archives of Microbiology (2021)

-

Streptomyces griseocarneus R132 expresses antimicrobial genes and produces metabolites that modulate Galleria mellonella immune system

3 Biotech (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.