Abstract

Exposure to bisphenol A (BPA) in utero is associated with adverse health outcome of the offspring. Differential DNA methylation at specific CpG sites may link BPA exposure to health impacts. We examined the association of prenatal BPA exposure with genome-wide DNA methylation changes in cord blood in 277 mother-child pairs in the Hokkaido Study on Environment and Children’s Health, using the Illumina HumanMethylation 450 BeadChip. We observed that a large portion of BPA-associated differentially methylated CpGs with p-value < 0.0001 was hypomethylated among all newborns (91%) and female infants (98%), as opposed to being hypermethylated (88%) among males. We found 27 and 16 CpGs with a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 in the analyses for males and females, respectively. Genes annotated to FDR-corrected CpGs clustered into an interconnected genetic network among males, while they rarely exhibited any interactions in females. In contrast, none of the enrichment for gene ontology (GO) terms with FDR < 0.05 was observed for genes annotated to the male-specific CpGs with p < 0.0001, whereas the female-specific genes were significantly enriched for GO terms related to cell adhesion. Our epigenome-wide analysis of cord blood DNA methylation implies potential sex-specific epigenome responses to BPA exposure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) is associated with dysfunctions of hormone-mediated processes, such as metabolism, energy balance, thyroid and reproductive functions, immune functions, and neurodevelopment1,2,3,4. In particular, the prenatal and early postnatal period is highly vulnerable to EDC exposure as it is the time of developmental programming essential for organogenesis and tissue differentiation5.

Bisphenol A (BPA) is a chemical widely used in consumer products, including plastics, dental sealants, food containers, and thermal receipts6. Biomonitoring studies reported BPA was detectable in the dust, air particles, and water7. Humans are exposed to this compound through their diet, inhalation of house dust, and skin contact8. As a result, BPA is widely found in different populations, including children and pregnant women9,10. Furthermore, BPA is a known EDC; it has been shown to have estrogenic effects through binding to the estrogen receptors (ERs)11. BPA can also activate a variety of growth-related transcription factors and bind effectively to several nuclear receptors involved in cell maturation12,13. Additionally, BPA has agonistic and antagonistic effects on thyroid function14. Numerous experimental studies indicate that early-life exposure to BPA affects metabolic, reproductive, and behavioral phenotypes of the offspring and has sustained effects on future health trajectories15,16,17. Given its widespread human exposure and endocrine-disrupting effects, developmental BPA exposure could have adverse effects on human health. Epidemiological studies have shown that prenatal BPA exposures are associated with various health outcomes including altering birth size18,19, disruption of hormone balance20,21, obesity22,23, immune function impairment24,25, and neurobehavioral problems26,27,28,29,30,31,32, and most of these effects were sex-specific.

The actual mechanisms accounting for long-term effects of early-life exposure to EDCs remain unclear. Epigenetic is the study of the biological mechanism of heritable and reversible chemical modifications of chromatin that regulate gene expression without changing the DNA sequence33. Epigenetic alterations play a role in embryonic development and cellular differentiation34 and can be affected by environmental factors, primarily when this occurs within the sensitive developmental windows35. Accumulating evidence suggests that epigenetic alterations may link developmental EDC exposure with susceptibility to diseases later in life36,37,38,39. DNA methylation is among the most studied mechanisms of epigenetic regulation40 and may be one of the mechanisms by which BPA exposure exerts its biological effects41. Evidence from experimental studies suggests that DNA methylation changes in the offspring can occur in response to developmental BPA exposure40,42,43,44. Previous human cohort studies showed that prenatal BPA exposure associated with DNA methylation profiles of fetal liver genes45,46,47 and metabolism-related genes of the offspring48,49. Furthermore, it has been shown that BPA-induced epigenetic effects are usually sex-specific49,50.

Genome-wide methylation analysis allows unbiased assessment of epigenetic alterations in relation to the environmental factors51; however, only one cohort study from Germany showed an association between maternal urinary BPA levels (low levels with <7.6 ng/mg creatinine; n = 102 and high levels with >15.9 ng/mg creatinine; n = 101) and genome-wide DNA methylation in cord blood samples regardless of infant’s sex52. We aimed to examine cord blood DNA methylation changes in association with BPA exposure by an epigenome-wide association study (EWAS) in a Japanese cohort. Besides, analyses were also performed to determine sex-specific differences in BPA exposure-associated methylation profiles.

Results

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the participants with the corresponding median BPA concentrations in cord blood are described in Table 1. BPA was detected in 68.6% of cord blood samples. The median of cord blood BPA was 0.050 ng/mL (Interquartile range (IQR): <the limit of quantification (LOQ) – 0.075). The average ± standard deviation (s.d.) age of the mothers was 30.0 ± 4.9 years. Of the 277 newborns, 123 (44.4%) were male. None of the characteristics shown in Table 1 were significantly associated with BPA levels. The comparison of BPA levels and maternal and infant characteristics between infant sexes are shown in Supplementary Table S1. There was a significant difference in birth weight between the infant sexes. Besides, the median level of BPA, maternal characteristics, and gestational age were not significantly different between sexes. The percentage of subjects with BPA values below the LOQ among the females (32.5%) was slightly higher than that among the males (30.1%).

Epigenome-wide association study of in utero BPA exposure

Our analysis showed that p-value distribution of all CpGs was generally similar to the theoretical distribution among all newborns (in the quantile-quantile plot, genomic inflation factor: λ = 1.01), whereas the p-values distribution deviated from the theoretical distribution among male and female infants (λ = 1.22 and λ = 1.35, respectively) as shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. Volcano plots of EWAS analyses for all newborns, male infants, and female infants showed an imbalance in positive versus negative methylation changes (Fig. 1A), suggesting a global methylation shift. As we had too few false discovery rate (FDR)-significant findings to confirm the sex-specific effect on DNA methylation changes, we compared CpGs with uncorrected p-value < 0.0001 (45 CpGs in all newborns, 269 CpGs in male infants, and 291 CpGs in female infants) and observed a large portion of these was hypomethylated among all newborns (91%) and female infants (98%) (Fig. 1B). In contrast, of the 269 CpGs among male infants, 236 CpGs (88%) were hypermethylated (Fig. 1B). All CpGs with p-value < 0.0001 are listed in Supplementary Tables S2–S4. Of those, two CpGs; cg25857471 (DPCR1) and cg13481969 (LOC441455), were overlapping between all newborns and males, and nine CpGs; cg08710564 (ST5), cg23279887 (TMEM161A), cg11820931 (DDX21), cg23047671 (LINC01019), cg14048686 (PPP1R26-AS1), cg27624753 (CRAMP1L), cg02344993 (CLTC), cg27038101 (CTRL), cg12393623 (METRNL), were overlapping between all newborns and females (please refer to the Supplementary Fig. S2 and Table S2). There were no overlaps between males and females.

(A) Volcano plots of the log10(p-values) versus the magnitude of effect (Coef) for the genome-wide analysis of the association between BPA exposure and DNA methylation in cord blood among all newborns, male infants, and female infants. Horizontal lines represent a p-value < 0.0001. (B) The percentage of hypo and hypermethylated CpGs with p < 0.0001 found in the analyses for all, male, and female infants.

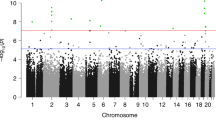

Next, we studied differentially methylated probes (DMPs) with epigenome-wide significant methylation changes; an FDR q-value < 0.05. As shown in Manhattan plots of genome-wide analyses (Fig. 2), we observed 28 male- and 16 female-specific DMPs that are listed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. In the male-only analysis, BPA levels in cord blood were associated with hypermethylation of 22 DMPs and hypomethylation of 6 DMPs. Among the female infants, BPA levels were associated with hypomethylation of 16 DMPs. There were no CpGs with FDR < 0.05 in all newborns (Fig. 2A); however, the directions of methylation changes at DMPs observed in all infants were consistent with those found in the sex-stratified analyses (see Tables 2 and 3).

We explored whether FDR-significant DMPs identified in the Sapporo cohort also showed the same direction of methylation change in a Taiwan cohort (the right columns in Tables 2 and 3). Of the DMPs, one male- and two female-specific DMPs were not available for the analysis. Ten of the fourteen female-specific DMPs showed the same direction of methylation changes (hypomethylation) in both cohorts, whereas the direction of methylation changes in the male-specific DMPs was not reproducible (9 of 27 male-specific DMPs).

Sensitivity analyses showed that neither maternal smoking nor subjects with BPA levels below LOQ were associated with male-specific hypermethylation and female-specific hypomethylation, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. The percentage of hypermethylated CpGs among males in the analyses for maternal smoking and BPA levels below the LOQ were 82% and 92%, respectively. Among females, 94% of CpGs for maternal smoking and 87% of CpGs for BPA levels below were hypomethylated. The analysis for the association between methylation and tertile BPA levels, which were <0.041, 0.041–0.066, and >0.066 ng/mL, also showed predominant hypermethylation (94%) among males and hypomethylation (93%) among females (Supplementary Fig. S3) as with the analyses for ln-transformed BPA levels. CpGs with p-value < 0.0001 in the analyses for tertile BPA levels are listed in the Supplementary Tables S5–S7. Twenty-seven of the 28 male-specific DMPs and all sixteen female-specific DMPs still showed a p-value < 0.0001 in the sex-stratified analyses for tertile BPA (Supplementary Tables S6 and S7). It is noted that those additional analyses again showed high inflation factors (from 1.2 to 1.4). We have also examined associations between the predicted cord blood cell proportions from the 450 K array and BPA levels among all infants, infants with <LOQ, and >LOQ and found no significant correlation between them (Supplementary Table S8).

Furthermore, we also investigated two CpGs in MEST and RAB40B identified by a previous EWAS analysis on prenatal BPA exposure and cord blood DNA methylation52 based on our dataset among all newborns. The CpG in MEST displayed the same direction of methylation change, although it did not reach statistical significance. On the contrary, the trend was not replicated at CpG in RAB40B. Meanwhile, an animal model showed that the effect of prenatal exposure to BPA on the brain was mediated by X-chromosome inactivation53. An enrichment of hypomethylated sites on the X-chromosome due to increasing BPA concentrations was observed in young girls54. It is possible that prenatal BPA exposure has effects on DNA methylation alterations at CpGs on X-chromosome. To examine the possibility, we performed sex-stratified analyses, including CpGs on the X-chromosome; however, we observed no enrichment of differentially methylated CpGs on X-chromosome.

Network analysis of DMPs

Genes annotated to DMPs (28 male-specific and 16 female-specific genes) were analyzed by network analysis using GeneMANIA55 (https://genemania.org/) that is based on known genetic and physical interactions, shared pathways and protein domains as well as protein co-expression data. Two male-specific genes (LOC401242 and LOC441455) were not available for GeneMANIA analysis; therefore, only 26 of the 28 male-specific genes were included in this analysis. The analyses showed that all male-specific genes, except one (C6orf52), formed a compact cluster showing co-expression, genetic interaction, and colocalization (see Fig. 3). None of the networks of pathways, physical infarctions, predicted, or shared protein domains were extracted by GeneMANIA. Conversely, among the 16 female-specific genes, six genes showed three disperse clusters of co-expression (Fig. 4). The rest of the genes showed no interaction with others.

Gene ontology analysis

We also investigated the underlying biology that may be affected by BPA-associated variations in a sex-specific manner. As we were not able to perform enrichment analysis on only 28 DMPs in males and 16 DMPs in females, we tested for gene ontology (GO) terms and Kyoto Encyclopedia Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways56 enrichment among the CpGs associated with BPA levels with p < 0.0001. Four GO terms among the female infants were significant at FDR < 0.05, as shown in Table 4. None of the GO terms among the males were substantial at the FDR threshold. In contrast, the gene set for both sexes were enriched with genes from numerous KEGG pathways. The top ten enriched pathways ranked by the lowest p-value, excluding the pathways for diseases, are shown in Table 5. Among males, six of the ten pathways are involved in signal transduction – MAPK signaling pathway, AMPK signaling pathway, Rap1 signaling pathway, Signaling pathways regulating pluripotency of stem cells, mTOR signaling pathway, and Phospholipase D signaling pathway. Among the ten pathways enriched among the female, three pathways were associated with the endocrine system – estrogen signaling pathway, relaxin signaling pathway, and parathyroid hormone synthesis, secretion, and action.

Discussion

Even though BPA levels in this study were relatively lower20 than those in the previous studies on cord blood BPA levels19,57,58, we found substantial sex differences in methylation changes associated with BPA exposure. Among males, BPA exposure was more frequently associated with hypermethylation than with hypomethylation, whereas it was associated predominantly with hypomethylation among female infants. Genes annotated to these CpGs also showed sex differences in the genetic network and functional enrichment analyses. Our results suggest that even at low levels, BPA exposure may impact DNA methylation status at birth in a sex-specific manner.

Among males, the top hit showing hypermethylation, cg20981000, is located in the intergenic region (IGR) of MTMR6, which encodes myotubularin related protein 6 (Fig. 2 and Table 2). Notably, based on Comparative Toxicogenomic Database (CTD, hhtp://ctdbase.org//) which provides manually curated information on environmental chemicals, interacting genes, and associated health effects in human and animal models, experimental models have reported that exposure to BPA resulted in decreased expression of MTMR6 mRNA59 and increased DNA methylation of MTMR6 gene60. In the female-only analysis, the most significant DMP (cg22927302) was mapped to SEMA3B, which encodes Semaphorin 3B (Fig. 2 and Table 3). BPA exposure also affected the expression of SEMA3B mRNA61,62 and decreased DNA methylation of SEMA3B promoter63 in experimental models. In addition, according to CTD, among nine genes annotated to DMPs with p-value < 0.0001 overlapping between all newborns and females, methylation and/or expression of seven genes: ST5 (Suppression of Tumorigenicity 5)61,64,65, TMEM161A (Transmembrane Protein 161A)61,66, DDX21 (DExD-Box Helicase 21)60,61,66,67, CRAMP1L (Cramped Chromatin Regulator Homolog 1)59,61, CLTC (Clathrin Heavy Chain)61, CTRL (Chymotrypsin Like)61,65,66, and METRNL (Meteorin Like, Glial Cell Differentiation Regulator)61 were disrupted by in vivo/vitro BPA exposure. Meanwhile, the magnitude of the effect on DNA methylation change represented in the absolute value of the regression coefficient (Coef) at the DMPs was generally small (see Tables 2 and 3). Since DNA methylation is tissue-specific, a small difference in methylation levels may result from a small fraction of cells exhibiting the difference at a particular CpG. Among FDR-corrected DMPs, only one male-specific DMP (cg01119278) in the gene body of DDO (D-Aspartate Oxidase) showed a positive association with the value of Coef >0.05 (Table 2). According to CTD, an in vitro study has shown that exposure to BPA decreased mRNA level of DDO61. We also found a DMP mapped to DNMT3B in the analysis for male infants (Table 2). Gestational BPA exposure can alter the expression of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) in the mouse brain, altering methylation and expression of ERα41. This is likely one of the mechanisms by which BPA exerts its endocrine-disrupting effects16. However, there might be other epigenetic mechanisms, such as histone modification68,69 or expression non-cording RNAs70,71,72,73,74, underlying prenatal BPA exposure. Further studies are needed to investigate this issue.

Despite no differences in BPA levels between the sexes (Supplementary Table S1), methylation changes derived from exposures to BPA showed notable sex-specific differences – the inversed direction of effects on methylation changes might be responsible for the lack of significant changes among all newborns. The observed preference of BPA-induced hypomethylation in females, as opposed to hypermethylation among males, is consistent with the findings from studies on blood-based methylation alterations that showed BPA-induced hypomethylation in women75 and young girls54. However, we observed no enrichment of hypomethylated CpGs on X-chromosome as noted in young girls54. In the gene-specific analyses, Montrose et al.49 showed that prenatal BPA exposure was associated with a decrease in cord blood IGF2 and PPARA methylation among females. BPA is considered to predominantly induce hypomethylation in females, while its effects in males are unclear76.

Replication analyses using a different population is vital to validate the result from epigenome-wide analyses. It is desirable that the platform, sample matrices, statistical model, and ancestry are aligned in both cohorts. As far as we knew, among Asian cohorts, only the Taiwan cohort had both maternal BPA concentration and the 450 K methylation data in cord blood. In the Taiwan cohort, the concentrations of BPA in maternal urine samples during the third trimester were measured77. According to Montrose et al.49, the geometric mean and standard deviation for BPA concentrations measured in urine and plasma were similar; however, the distribution range of BPA levels in the maternal urine in the Taiwan cohort (0.03 to 125.75 μg/g creatine) was broader compared to the distribution of cord blood BPA levels in the Sapporo cohort (LOQ; 0.04 ng/mL to 0.22 ng/mL). Despite the differences in sample matrices and BPA measuring timing, ten of the 14 female-specific DMPs (71%) had the same direction of methylation change (hypomethylation) in both Sapporo and Taiwanese cohorts. Whereas, only nine of the 27 male-specific DMPs showed the same direction of methylation change in both cohorts (Tables 2 and 3). Although we should notice that the concentrations of BPA were determined using different biological specimens, it is possible that the variation in BPA-associated effect spectrum over BPA levels78 may explain the very limited agreement in the males between these two cohorts. The difference in the time of BPA measurement and/or shorter gestational age may also account for the disparities. As mentioned above, the effects of BPA on DNA methylation in male infants has not been clarified76. Further studies would be required to evaluate its effects among males.

Sex-stratified analyses showed inflation of the estimates, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. We applied the ComBat method to reduce batch effects and adjusted for cord cell proportion estimates to remove issues associated with cell heterogeneity. Given that there was no inflation among all newborns, the inflation in sex-stratified analysis cannot just reflect strong signals for some phenotypes (e.g., gestational age, birth weight, and maternal smoking). For instance, the sensitivity analyses showed that the observed sex-specific associations between BPA exposure and methylation alterations were mostly independent of maternal smoking during pregnancy that was most likely a residual confounder79,80. Sample size reduced by half in sex-stratified analyses might cause significant deviation from the expected distribution of p-value. Nevertheless, two randomly divided groups did not show inflation (data not shown). Another factor that might be driving a considerable proportion of significant results was a massive tail of subjects with BPA levels below LOQ. However, both analyses excluding subjects with BPA levels below the LOQ and for tertiles of BPA levels again showed the inflated results with male-specific hypermethylation and female-specific hypomethylation (Supplementary Fig. S2). Although there remains a possibility that population substructure in sex-stratified groups may bias or influence the results, it is assumed that BPA exposure might affect genome-wide methylation levels with a sex-specific association. Whereas, over inflation might lead to false discoveries in our analyses. We need to replicate our findings by further investigations with larger sample sizes and comparable exposure ranges.

In addition to the opposed direction of effect between sexes, the network analyses of genes annotated to FDR-corrected DMPs showed the sex-difference (Figs 3 and 4). The male-specific genes clustered into a complex interconnected network, whereas the female-specific genes were isolated. In contrast, with regard to the gene pathways, the female-specific CpGs with p-value < 0.0001 included genes that were significantly enriched for GO terms related to cell adhesion (FDR < 0.05) – homophilic cell adhesion via plasma membrane adhesion molecules, cell-cell adhesion via plasma membrane adhesion molecules, cell-cell adhesion, and calcium ion binding (Table 4). On the contrary, genes annotated to the male-specific probes were not enriched in any GO terms with an FDR threshold. With respect to KEGG pathways, it should be noted that enrichment in the MAPK signaling pathway and the estrogen signaling pathway were observed among the genes annotated to male- and female-specific probes, respectively. According to Singh and Li81, a mitogen-activated protein (MAPK) and estrogen receptor (ESR) were included in most frequently curated BPA-interacting genes/proteins. Nevertheless, it is possible that the observed differences between infant sex could relate to cord blood cell proportions. We compared the cell type proportions between sex and found a significant difference in the CD8T cell type (Supplementary Table S9). There remains a possibility that different cell compositions influence the observed distinct results between infant sexes.

A previous study on epigenetic effects of prenatal BPA exposure using the genome-wide analysis reported cord blood DNA methylation differences at two CpGs in MEST and RAB40B between subjects with low (n = 102, <7.6 ng/mg creatinine) and high (n = 101, >15.9 ng/mg creatinine) maternal urinary BPA levels at 34 weeks of pregnancy in Leipzig, Germany52. Since the analysis was not stratified by sex, to be precise, we investigated the methylation changes at the CpGs on MEST and RAB40B based on our dataset among all newborns. The CpG in MEST displayed the same direction of methylation change as those reported by Junge et al.52, although it did not reach statistical significance. On the contrary, the trend was not replicated at CpG in RAB40B. It is plausible that differences in sample matrices, statistical model, and ancestry might be partially responsible for the disagreement. We need more research focused on sex-specific associations to elucidate the potential role of BPA in methylation alteration.

In previous studies using the same Sapporo cohort, we had reported that BPA exposure is associated with reproductive hormone levels of neonates20, child behavioral problems at an early age28, and fetal metabolic-related biomarkers82 in a sex-specific manner. Other epidemiological studies also showed that the impact of developmental BPA exposure on neurobehavioral functions might differ between the sexes83,84. Harley et al.22 showed that increasing BPA concentrations in mothers during pregnancy was associated with decreased body mass index (BMI), body fat, and overweight/obesity at nine years of age in girls but not boys. Sex-specific methylomic profiles may underlie the differences in gene expression and functions85 and contribute to a differential susceptibility between males and females to adverse health outcomes as seen in animal models, which were used to evaluated life-course sexually dimorphic health effects following developmental BPA expouure50,68,86,87,88. Cell adhesion molecules are utilized in various steps during embryonic development and cellular differentiation. Possibly, female-specific hypomethylation on genes related to cell adhesion may increase the gene expression and mediate metabolic outcomes, including changes in body weight and body fat. The effect of methylation changes identified herein on sex-specific health outcomes needs to be elucidated in a later stage. Meanwhile, our results corroborate the need for studies on the sex-specific effects of EDCs on DNA methylation alterations.

The following limitations of this study should be considered. First, this is a cross-sectional study, and we did not determine the cause and effect relationship. Further, there have been concerns about using a single measurement of the cord blood sample as a representation of the long-term prenatal exposure due to the short half-life of BPA. Furthermore, we evaluated BPA levels in maternal urine samples during the third trimester for the replication analysis. It has been reported that BPA concentrations measured in urine and plasma are correlated49; however, little is known about the correlation between BPA levels with sampled at different times. Further studies should be conducted to evaluate whether one-time exposure measurement would reflect BPA exposure during pregnancy. Second, DNA methylation was measured using unfractionated cord blood. BPA is known to affect multiple tissues. Whether the associations observed in this study may reflect associations between prenatal BPA exposure and the methylation at target tissues is unknown. Third, we included participants for whom cord blood samples were available, thus limiting the scope only to mothers who delivered vaginally. It is thus possible that relatively healthier children were included in our analysis, and we may have underestimated the effects of BPA exposure. Fourth, the exposure levels of BPA were relatively low. It is possible that our results may not be generalized to the population with high exposure levels. Fifth, we analyzed CpGs showing a p-value < 0.0001, not epigenome-wide significance, to confirm the sex-specific effect on DNA methylation. That might give rise to false discoveries in our analyses. Lastly, there was a limited statistical power of our sample size for the analysis stratified by sex. Additionally, we could not perform the stratified analysis with sex for the Taiwanese cohort because of the small sample size. Therefore, we recommend further studies with larger sample sizes and comparable exposure levels.

In conclusion, this epigenome-wide study suggested that even relatively low levels of exposure to BPA impact DNA methylation status at birth in a sex-specific manner. There may be a potential susceptibility difference in relation to BPA exposure between males and females. Further studies are needed to confirm our findings and to investigate their relevance to sex-specific adverse health outcomes.

Methods

Study population

Participants were enrolled in the Sapporo cohort of the Hokkaido Study on Environment and Children’s Health89,90,91. Briefly, we recruited pregnant women at 23–35 weeks of gestation between 2002 and 2005 from the Toho Hospital (Sapporo, Japan). After the second trimester during their pregnancy, the participants completed the self-administered questionnaire containing baseline information including family income, educational level, parity history, and pregnancy health information including smoking status, alcohol consumption, and caffeine intake. Information on pregnancy complications, gestational age, infant sex, and birth size was obtained from medical records.

Measurement of bisphenol A

Whole cord blood was collected immediately after birth and stored at −80 °C prior to analysis. BPA levels were measured in cord blood by using isotope dilution liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (ID-LC/MS/MS) at IDEA Consultants, Inc. (Shizuoka, Japan) as described previously10. The LOQ of BPA was 0.04 ng/mL.

450 K DNA methylation analysis

Cord blood DNA methylation at 485,577 CpGs was quantified using the Infinium HumanMethylation 450 BeadChip (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) by G&G Science Co., Ltd. (Matsukawa, Fukushima, Japan). Details for the 450 K methylation analysis are described elsewhere92. Samples were run across five plate batches and were assigned randomized location across plates. After quality control93, functional normalization94 was applied to the raw data and normalized beta (β) values, ranging from 0–1 for 0% to 100% methylated, were obtained for the 292 cord blood samples. Probes with a detection p-value > 0.05 in more than 25% of samples, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-affected probes, cross-reactive probes identified by Chen et al.95, and probes on sex chromosomes were removed. As a result, 426,413 CpG probes were included in the working set. We applied the ComBat method to adjust methylation data for the sample plate to reduce potential bias due to batch effects96. Combat-transformed M-values (logit-transformed β-values) were back-transformed to β-values that were used for subsequent data analyses.

Data analyses

Among the 514 participants of the Sapporo Cohort Study, 277 mother-infant pairs had both exposure and DNA methylation data. Supplementary Fig. S4 shows the distribution of BPA levels in 277 cord blood samples. For the 87 samples below the LOQ (0.04 ng/mL), we assigned a value of half the detection limit (0.02 ng/mL). Cord blood cell proportion was estimated by the method implemented in the R/Bioconductor package minfi97. Using limma package in R, robust linear regression analysis98 and empirical Bayesian method99 were applied to determine the associations of β-value at each CpG site with BPA natural log (ln)-transformed concentrations, adjusted for maternal age, educational levels, pre-pregnancy BMI, smoking during pregnancy, gestational age, infant sex, and cord blood cell estimates for CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, granulocytes, monocytes, B cell, and nucleated red blood cells. Adjustment covariates were selected from factors previously reported to be associated with exposure or cord blood DNA methylation. For multiple comparisons, p-values were adjusted by the FDR to obtain q-values. We further stratified the analysis by infant sex and compared CpGs with p-value < 0.0001 to confirm the sex-specific effect on DNA methylation changes. To address the potential residual confounding due to smoking79,80, we performed a sensitivity analysis, excluding infants with sustained maternal smoking during pregnancy (n = 43). Since 31.4% of BPA levels fell below the LOQ, we have also performed a sensitivity analysis excluding subjects with BPA values below LOQ (n = 87). Besides, we examined associations of tertiles of BPA levels with DNA methylation. Tertiles were <0.041, 0.041–0.066, and >0.066 ng/mL, respectively. Statistical analyses were performed using minfi, sva, and limma packages in R ver. 3.3.2 and Bioconductor ver. 3.3.

To further analyze underlying genetic networks of BPA-associated CpGs, we imported and analyzed genes related to DMPs surviving an FDR < 0.05 using GeneMANIA55 (https://genemania.org/) bioinformatics software with default parameters. We also assessed the differentially methylated CpGs with p-value < 0.0001 for functional enrichment with GO terms and KEGG pathways56 via the gometh function in the missMethyl package in R/Bioconductor100.

Replication study for DMPs in an independent cohort

Eleven mother-infant pairs from a Taiwanese cohort had both maternal urine samples and cord blood samples. Details of the study population have been published elsewhere101. Briefly, women were recruited from an obstetrics clinic in Cathay General Hospital (CGH) in Taipei, Taiwan from March to December 2010. The eligibility criteria included an age of 18–45 years, <13 weeks pregnant with detection of the fetal heartbeat at the first prenatal visit, and planning to deliver at CGH. The concentrations of BPA in urine samples from pregnant women during the third trimester were measured using ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with time-of-flight mass spectrometry as described by Huang et al.77. The characteristics of the eleven mother-infant pairs are presented in Supplementary Table S10. Genome-wide DNA methylation was assessed as follows: cord blood DNA (500 ng) was subjected to bisulfite conversion using a Zymo EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). Following bisulfite conversion, DNA was hybridized to the Infinium HumanMethylation 450 BeadChip (Illumina Inc.) and scanned according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Raw data were processed with the Chip Analysis Methylation Pipeline Bioconductor package (v1.8.0) in the R environment. Probes meeting any of the following conditions were removed: (1) internal controls, (2) detected p-value < 0.01, (3) <3 beads in at least 5% of the samples per probe, (4) aligned to multiple locations, (5) contained SNPs, or (6) were located on sex chromosomes. A total of 433,523 probes passed the filtering process, and intra-array normalization was performed with the BMIQ (Beta MIxture Quantile dilation) method. The ComBat method96 was applied to reduce the batch effect. Finally, β-values batch-corrected were obtained. Linear regression analyses adjusted for the sex of child were used to determine the associations of the β-value with ln-transformed BPA levels. We assumed that we could compare the direction of methylation changes related to BPA levels between two cohorts using β-values batch-corrected by the ComBat even though the normalization methods were different. Due to the minimal sample size (n = 11), we did not stratify the analysis by sex.

Ethics

Written informed consents were obtained from all participants. The institutional Ethical Board for human gene and genome studies at the Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine and the Hokkaido University Center for Environmental and Health Science approved the study protocol. The study protocol of Taiwan cohort was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cathay General Hospital (CGH) in Taipei, Taiwan. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

References

Bansal, A., Henao-Mejia, J. & Simmons, R. A. Immune System: An Emerging Player in Mediating Effects of Endocrine Disruptors on Metabolic Health. Endocrinology 159, 32–45, https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2017-00882 (2018).

Moosa, A., Shu, H., Sarachana, T. & Hu, V. W. Are endocrine disrupting compounds environmental risk factors for autism spectrum disorder? Hormones and behavior 101, 13–21, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2017.10.003 (2018).

Braun, J. M. Early-life exposure to EDCs: role in childhood obesity and neurodevelopment. Nature reviews. Endocrinology 13, 161–173, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2016.186 (2017).

Heindel, J. J. et al. Metabolism disrupting chemicals and metabolic disorders. Reproductive toxicology (Elmsford, N.Y.) 68, 3–33, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2016.10.001 (2017).

Heindel, J. J., Skalla, L. A., Joubert, B. R., Dilworth, C. H. & Gray, K. A. Review of developmental origins of health and disease publications in environmental epidemiology. Reproductive toxicology (Elmsford, N.Y.) 68, 34–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2016.11.011 (2017).

Vandenberg, L. N., Hauser, R., Marcus, M., Olea, N. & Welshons, W. V. Human exposure to bisphenol A (BPA). Reproductive toxicology (Elmsford, N.Y.) 24, 139–177, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.07.010 (2007).

Asimakopoulos, A. G., Thomaidis, N. S. & Koupparis, M. A. Recent trends in biomonitoring of bisphenol A, 4-t-octylphenol, and 4-nonylphenol. Toxicology letters 210, 141–154, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.07.032 (2012).

Vandenberg, L. N. et al. Hormones and endocrine-disrupting chemicals: low-dose effects and nonmonotonic dose responses. Endocrine reviews 33, 378–455, https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2011-1050 (2012).

Covaci, A. et al. Urinary BPA measurements in children and mothers from six European member states: Overall results and determinants of exposure. Environmental research 141, 77–85, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2014.08.008 (2015).

Yamamoto, J. et al. Quantifying bisphenol A in maternal and cord whole blood using isotope dilution liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry and maternal characteristics associated with bisphenol A. Chemosphere 164, 25–31, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.08.001 (2016).

Meeker, J. D., Calafat, A. M. & Hauser, R. Urinary bisphenol A concentrations in relation to serum thyroid and reproductive hormone levels in men from an infertility clinic. Environmental science & technology 44, 1458–1463, https://doi.org/10.1021/es9028292 (2010).

Galloway, T. et al. Daily bisphenol A excretion and associations with sex hormone concentrations: results from the InCHIANTI adult population study. Environmental health perspectives 118, 1603–1608, https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1002367 (2010).

Mendiola, J. et al. Are environmental levels of bisphenol a associated with reproductive function in fertile men? Environmental health perspectives 118, 1286–1291, https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1002037 (2010).

Lassen, T. H. et al. Urinary bisphenol A levels in young men: association with reproductive hormones and semen quality. Environmental health perspectives 122, 478–484, https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1307309 (2014).

Le Magueresse-Battistoni, B., Multigner, L., Beausoleil, C. & Rousselle, C. Effects of bisphenol A on metabolism and evidences of a mode of action mediated through endocrine disruption. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 475, 74–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2018.02.009 (2018).

Nesan, D., Sewell, L. C. & Kurrasch, D. M. Opening the black box of endocrine disruption of brain development: Lessons from the characterization of Bisphenol A. Hormones and behavior 101, 50–58, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2017.12.001 (2018).

Viguie, C. et al. Evidence-based adverse outcome pathway approach for the identification of BPA as en endocrine disruptor in relation to its effect on the estrous cycle. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 475, 10–28, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2018.02.007 (2018).

Philippat, C. et al. Exposure to phthalates and phenols during pregnancy and offspring size at birth. Environmental health perspectives 120, 464–470, https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1103634 (2012).

Chou, W. C. et al. Biomonitoring of bisphenol A concentrations in maternal and umbilical cord blood in regard to birth outcomes and adipokine expression: a birth cohort study in Taiwan. Environmental health: a global access science source 10, 94, https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069x-10-94 (2011).

Minatoya, M. et al. Cord Blood Bisphenol A Levels and Reproductive and Thyroid Hormone Levels of Neonates: The Hokkaido Study on Environment and Children’s Health. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.) 28(Suppl 1), S3–s9, https://doi.org/10.1097/ede.0000000000000716 (2017).

Romano, M. E. et al. Gestational urinary bisphenol A and maternal and newborn thyroid hormone concentrations: the HOME Study. Environmental research 138, 453–460, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2015.03.003 (2015).

Harley, K. G. et al. Prenatal and postnatal bisphenol A exposure and body mass index in childhood in the CHAMACOS cohort. Environmental health perspectives 121, 514–520, https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1205548 (2013).

Vafeiadi, M. et al. Association of early life exposure to bisphenol A with obesity and cardiometabolic traits in childhood. Environmental research 146, 379–387, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2016.01.017 (2016).

Gascon, M. et al. Prenatal exposure to bisphenol A and phthalates and childhood respiratory tract infections and allergy. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 135, 370–378, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.09.030 (2015).

Spanier, A. J. et al. Bisphenol a exposure and the development of wheeze and lung function in children through age 5 years. JAMA pediatrics 168, 1131–1137, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1397 (2014).

Braun, J. M. et al. Prenatal environmental chemical exposures and longitudinal patterns of child neurobehavior. Neurotoxicology 62, 192–199, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2017.07.027 (2017).

Braun, J. M. et al. Associations of Prenatal Urinary Bisphenol A Concentrations with Child Behaviors and Cognitive Abilities. Environmental health perspectives 125, 067008, https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp984 (2017).

Minatoya, M. et al. Cord blood BPA level and child neurodevelopment and behavioral problems: The Hokkaido Study on Environment and Children’s Health. The Science of the total environment 607–608, 351–356, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.060 (2017).

Minatoya, M. et al. Prenatal exposure to bisphenol A and phthalates and behavioral problems in children at preschool age: the Hokkaido Study on Environment and Children’s Health. Environ Health Prev Med 23, 43, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-018-0732-1 (2018).

Miodovnik, A. et al. Endocrine disruptors and childhood social impairment. Neurotoxicology 32, 261–267, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2010.12.009 (2011).

Perera, F. et al. Prenatal bisphenol a exposure and child behavior in an inner-city cohort. Environmental health perspectives 120, 1190–1194, https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1104492 (2012).

Roen, E. L. et al. Bisphenol A exposure and behavioral problems among inner city children at 7–9 years of age. Environmental research 142, 739–745, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2015.01.014 (2015).

Nilsson, E. & Ling, C. DNA methylation links genetics, fetal environment, and an unhealthy lifestyle to the development of type 2 diabetes. Clinical epigenetics 9, 105, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-017-0399-2 (2017).

Breton, C. V. et al. Small-Magnitude Effect Sizes in Epigenetic End Points are Important in Children’s Environmental Health Studies: The Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research Center’s Epigenetics Working Group. Environmental health perspectives 125, 511–526, https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp595 (2017).

Jirtle, R. L. & Skinner, M. K. Environmental epigenomics and disease susceptibility. Nature reviews. Genetics 8, 253–262, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2045 (2007).

Barouki, R. et al. Epigenetics as a mechanism linking developmental exposures to long-term toxicity. Environment international 114, 77–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.02.014 (2018).

Ho, S. M. et al. Environmental factors, epigenetics, and developmental origin of reproductive disorders. Reproductive toxicology (Elmsford, N.Y.) 68, 85–104, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2016.07.011 (2017).

Tapia-Orozco, N. et al. Environmental epigenomics: Current approaches to assess epigenetic effects of endocrine disrupting compounds (EDC’s) on human health. Environmental toxicology and pharmacology 51, 94–99, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2017.02.004 (2017).

McLachlan, J. A. Environmental signaling: from environmental estrogens to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and beyond. Andrology 4, 684–694, https://doi.org/10.1111/andr.12206 (2016).

Mileva, G., Baker, S. L., Konkle, A. T. & Bielajew, C. Bisphenol-A: epigenetic reprogramming and effects on reproduction and behavior. International journal of environmental research and public health 11, 7537–7561, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110707537 (2014).

Kundakovic, M. & Jaric, I. The Epigenetic Link between Prenatal Adverse Environments and Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Genes 8, https://doi.org/10.3390/genes8030104 (2017).

Alonso-Magdalena, P., Rivera, F. J. & Guerrero-Bosagna, C. Bisphenol-A and metabolic diseases: epigenetic, developmental and transgenerational basis. Environmental epigenetics 2, dvw022, https://doi.org/10.1093/eep/dvw022 (2016).

Ideta-Otsuka, M., Igarashi, K., Narita, M. & Hirabayashi, Y. Epigenetic toxicity of environmental chemicals upon exposure during development - Bisphenol A and valproic acid may have epigenetic effects. Food and chemical toxicology: an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association 109, 812–816, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2017.09.014 (2017).

Singh, S. & Li, S. S. Epigenetic effects of environmental chemicals bisphenol A and phthalates. International journal of molecular sciences 13, 10143–10153, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms130810143 (2012).

Nahar, M. S., Kim, J. H., Sartor, M. A. & Dolinoy, D. C. Bisphenol A-associated alterations in the expression and epigenetic regulation of genes encoding xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes in human fetal liver. Environmental and molecular mutagenesis 55, 184–195, https://doi.org/10.1002/em.21823 (2014).

Nahar, M. S., Liao, C., Kannan, K., Harris, C. & Dolinoy, D. C. In utero bisphenol A concentration, metabolism, and global DNA methylation across matched placenta, kidney, and liver in the human fetus. Chemosphere 124, 54–60, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.10.071 (2015).

Faulk, C. et al. Detection of differential DNA methylation in repetitive DNA of mice and humans perinatally exposed to bisphenol A. Epigenetics 11, 489–500, https://doi.org/10.1080/15592294.2016.1183856 (2016).

Goodrich, J. M. et al. Adolescent epigenetic profiles and environmental exposures from early life through peri-adolescence. Environmental epigenetics 2, dvw018, https://doi.org/10.1093/eep/dvw018 (2016).

Montrose, L. et al. Maternal levels of endocrine disrupting chemicals in the first trimester of pregnancy are associated with infant cord blood DNA methylation. Epigenetics 13, 301–309, https://doi.org/10.1080/15592294.2018.1448680 (2018).

McCabe, C., Anderson, O. S., Montrose, L., Neier, K. & Dolinoy, D. C. Sexually Dimorphic Effects of Early-Life Exposures to Endocrine Disruptors: Sex-Specific Epigenetic Reprogramming as a Potential Mechanism. Current environmental health reports 4, 426–438, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-017-0170-z (2017).

Christensen, B. C. & Marsit, C. J. Epigenomics in environmental health. Frontiers in genetics 2, 84, https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2011.00084 (2011).

Junge, K. M. et al. MEST mediates the impact of prenatal bisphenol A exposure on long-term body weight development. Clinical epigenetics 10, 58, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-018-0478-z (2018).

Kumamoto, T. & Oshio, S. Effect of fetal exposure to bisphenol A on brain mediated by X-chromosome inactivation. The Journal of toxicological sciences 38, 485–494 (2013).

Kim, J. H. et al. Bisphenol A-associated epigenomic changes in prepubescent girls: a cross-sectional study in Gharbiah, Egypt. Environmental health: a global access science source 12, 33, https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069x-12-33 (2013).

Warde-Farley, D. et al. The GeneMANIA prediction server: biological network integration for gene prioritization and predicting gene function. Nucleic acids research 38, W214–220, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkq537 (2010).

Kanehisa, M., Goto, S., Kawashima, S. & Nakaya, A. The KEGG databases at GenomeNet. Nucleic acids research 30, 42–46 (2002).

Aris, A. Estimation of bisphenol A (BPA) concentrations in pregnant women, fetuses and nonpregnant women in Eastern Townships of Canada. Reproductive toxicology (Elmsford, N.Y.) 45, 8–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2013.12.006 (2014).

Kosarac, I., Kubwabo, C., Lalonde, K. & Foster, W. A novel method for the quantitative determination of free and conjugated bisphenol A in human maternal and umbilical cord blood serum using a two-step solid phase extraction and gas chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of chromatography. B, Analytical technologies in the biomedical and life sciences 898, 90–94, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchromb.2012.04.023 (2012).

Mahemuti, L. et al. Bisphenol A induces DSB-ATM-p53 signaling leading to cell cycle arrest, senescence, autophagy, stress response, and estrogen release in human fetal lung fibroblasts. Archives of toxicology 92, 1453–1469, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-017-2150-3 (2018).

Jadhav, R. R. et al. DNA Methylation Targets Influenced by Bisphenol A and/or Genistein Are Associated with Survival Outcomes in Breast Cancer Patients. Genes 8, https://doi.org/10.3390/genes8050144 (2017).

Ali, S. et al. Exposure to low-dose bisphenol A impairs meiosis in the rat seminiferous tubule culture model: a physiotoxicogenomic approach. PloS one 9, e106245, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106245 (2014).

Castro, B., Sanchez, P., Miranda, M. T., Torres, J. M. & Ortega, E. Identification of dopamine- and serotonin-related genes modulated by bisphenol A in the prefrontal cortex of male rats. Chemosphere 139, 235–239, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.06.061 (2015).

Jorgensen, E. M., Alderman, M. H. 3rd & Taylor, H. S. Preferential epigenetic programming of estrogen response after in utero xenoestrogen (bisphenol-A) exposure. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 30, 3194–3201, https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.201500089R (2016).

Lam, H. M. et al. Disrupts HNF4alpha-Regulated Gene Networks Linking to Prostate Preneoplasia and Immune Disruption in Noble Rats. Endocrinology 157, 207–219, https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2015-1363 (2016).

Zhang, Y., Yuan, C., Gao, J., Liu, Y. & Wang, Z. Testicular transcript responses in rare minnow Gobiocypris rarus following different concentrations bisphenol A exposure. Chemosphere 156, 357–366, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.05.006 (2016).

Villeneuve, D. L. et al. Ecotoxicogenomics to support ecological risk assessment: a case study with bisphenol A in fish. Environmental science & technology 46, 51–59, https://doi.org/10.1021/es201150a (2012).

Weng, Y. I. et al. Epigenetic influences of low-dose bisphenol A in primary human breast epithelial cells. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 248, 111–121, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2010.07.014 (2010).

Strakovsky, R. S. et al. Developmental bisphenol A (BPA) exposure leads to sex-specific modification of hepatic gene expression and epigenome at birth that may exacerbate high-fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 284, 101–112, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2015.02.021 (2015).

Chang, H. et al. Epigenetic disruption and glucose homeostasis changes following low-dose maternal bisphenol A exposure. Toxicology research 5, 1400–1409, https://doi.org/10.1039/c6tx00047a (2016).

Xie, X., Song, J. & Li, G. MiR-21a-5p suppresses bisphenol A-induced pre-adipocyte differentiation by targeting map2k3 through MKK3/p38/MAPK. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 473, 140–146, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.03.066 (2016).

Lin, Y. et al. Downregulation of miR-192 causes hepatic steatosis and lipid accumulation by inducing SREBF1: Novel mechanism for bisphenol A-triggered non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular and cell biology of lipids 1862, 869–882, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2017.05.001 (2017).

Wei, J., Ding, D., Wang, T., Liu, Q. & Lin, Y. MiR-338 controls BPA-triggered pancreatic islet insulin secretory dysfunction from compensation to decompensation by targeting Pdx-1. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 31, 5184–5195, https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.201700282R (2017).

Renaud, L. et al. The Plasticizer Bisphenol A Perturbs the Hepatic Epigenome: A Systems Level Analysis of the miRNome. Genes 8, https://doi.org/10.3390/genes8100269 (2017).

Reed, B. G. et al. Estrogen-regulated miRNA-27b is altered by bisphenol A in endometrial stromal cells. Reproduction (Cambridge, England), https://doi.org/10.1530/rep-18-0041 (2018).

Hanna, C. W. et al. DNA methylation changes in whole blood is associated with exposure to the environmental contaminants, mercury, lead, cadmium and bisphenol A, in women undergoing ovarian stimulation for IVF. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 27, 1401–1410, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/des038 (2012).

Martin, E. M. & Fry, R. C. Environmental Influences on the Epigenome: Exposure- Associated DNA Methylation in Human Populations. Annual review of public health 39, 309–333, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014629 (2018).

Huang, Y. F. et al. Prenatal Nonylphenol and Bisphenol A Exposures and Inflammation Are Determinants of Oxidative/Nitrative Stress: A Taiwanese Cohort Study. Environmental science & technology 51, 6422–6429, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b00801 (2017).

Faulk, C. et al. Bisphenol A-associated alterations in genome-wide DNA methylation and gene expression patterns reveal sequence-dependent and non-monotonic effects in human fetal liver. Environmental epigenetics 1, https://doi.org/10.1093/eep/dvv006 (2015).

Joubert, B. R. et al. DNA Methylation in Newborns and Maternal Smoking in Pregnancy: Genome-wide Consortium Meta-analysis. American journal of human genetics 98, 680–696, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.019 (2016).

Miyake, K. et al. Association between DNA methylation in cord blood and maternal smoking: The Hokkaido Study on Environment and Children’s Health. Scientific reports 8, 5654, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23772-x (2018).

Singh, S. & Li, S. S. Bisphenol A and phthalates exhibit similar toxicogenomics and health effects. Gene 494, 85–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2011.11.035 (2012).

Minatoya, M. et al. Association between prenatal bisphenol A and phthalate exposures and fetal metabolic related biomarkers: The Hokkaido study on Environment and Children’s Health. Environmental research 161, 505–511, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2017.11.052 (2018).

Giesbrecht, G. F. et al. Prenatal bisphenol a exposure and dysregulation of infant hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function: findings from the APrON cohort study. Environmental health: a global access science source 16, 47, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-017-0259-8 (2017).

Mustieles, V., Perez-Lobato, R., Olea, N., Fernandez, M. F. & Bisphenol, A. Human exposure and neurobehavior. Neurotoxicology 49, 174–184, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2015.06.002 (2015).

Xu, H. et al. Sex-biased methylome and transcriptome in human prefrontal cortex. Human molecular genetics 23, 1260–1270, https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddt516 (2014).

Anderson, O. S. et al. Novel Epigenetic Biomarkers Mediating Bisphenol A Exposure and Metabolic Phenotypes in Female Mice. Endocrinology 158, 31–40, https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2016-1441 (2017).

Kundakovic, M. et al. Sex-specific epigenetic disruption and behavioral changes following low-dose in utero bisphenol A exposure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110, 9956–9961, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1214056110 (2013).

Mao, Z. et al. Pancreatic impairment and Igf2 hypermethylation induced by developmental exposure to bisphenol A can be counteracted by maternal folate supplementation. Journal of applied toxicology: JAT 37, 825–835, https://doi.org/10.1002/jat.3430 (2017).

Kishi, R. et al. The Hokkaido Birth Cohort Study on Environment and Children’s Health: cohort profile—updated 2017. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine 22 (2017).

Kishi, R. et al. Ten years of progress in the Hokkaido birth cohort study on environment and children’s health: cohort profile–updated 2013. Environ Health Prev Med 18, 429–450, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12199-013-0357-3 (2013).

Kishi, R. et al. Cohort profile: the Hokkaido study on environment and children’s health in Japan. International journal of epidemiology 40, 611–618, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyq071 (2011).

Miura, R. et al. An epigenome-wide study of cord blood DNA methylations in relation to prenatal perfluoroalkyl substance exposure: The Hokkaido study. Environment international 115, 21–28, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.03.004 (2018).

Aryee, M. J. et al. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 30, 1363–1369, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu049 (2014).

Fortin, J. P. et al. Functional normalization of 450k methylation array data improves replication in large cancer studies. Genome biology 15, 503, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0503-2 (2014).

Chen, Y. A. et al. Discovery of cross-reactive probes and polymorphic CpGs in the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 microarray. Epigenetics 8, 203–209, https://doi.org/10.4161/epi.23470 (2013).

Leek, J. T., Johnson, W. E., Parker, H. S., Jaffe, A. E. & Storey, J. D. The sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 28, 882–883, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts034 (2012).

Bakulski, K. M. et al. DNA methylation of cord blood cell types: Applications for mixed cell birth studies. Epigenetics 11, 354–362, https://doi.org/10.1080/15592294.2016.1161875 (2016).

Fox, J. & Weisberg, S. Robust regression in R. (Sage, 2011).

Smyth, G. K. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Statistical applications in genetics and molecular biology 3, Article3, https://doi.org/10.2202/1544-6115.1027 (2004).

Phipson, B., Maksimovic, J. & Oshlack, A. missMethyl: an R package for analyzing data from Illumina’s HumanMethylation450 platform. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 32, 286–288, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv560 (2016).

Huang, Y. F. et al. Concurrent exposures to nonylphenol, bisphenol A, phthalates, and organophosphate pesticides on birth outcomes: A cohort study in Taipei, Taiwan. The Science of the total environment 607–608, 1126–1135, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.07.092 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge all the participants and staff in this study. This work was supported by the Environment Research and Technology Development Fund from the Japanese Ministry of the Environment (No. 5-1454), a Grant-in-Aid for Health Science Research from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (No. 201624002B; 17932352), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (No. 25253050; 16K15352; 16H02645; 18K10022), and Grants- Funding from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 100-2314-B-010-018-MY3; MOST 102-2314-B-010-031-MY3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.K. and R.K. conceived and designed this study. R.M., A.A., M.M., K.M., S.M., C.M., M.I. and R.K. contributed to the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data. M.M., J.Y. and T.M. performed the chemical analysis in blood samples of the Sapporo cohort. M.L.C. analyzed DNA methylation and chemical exposure of the Taiwan cohort. R.M., A.A., M.M., K.M., S.M., T.K. and R.K. wrote, revised, and finalized the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miura, R., Araki, A., Minatoya, M. et al. An epigenome-wide analysis of cord blood DNA methylation reveals sex-specific effect of exposure to bisphenol A. Sci Rep 9, 12369 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48916-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48916-5

This article is cited by

-

Gestational exposure to environmental chemicals and epigenetic alterations in the placenta and cord blood mononuclear cells

Epigenetics Communications (2024)

-

Fetal exposure to phthalates and bisphenols and DNA methylation at birth: the Generation R Study

Clinical Epigenetics (2022)

-

Epigenetics as a Biomarker for Early-Life Environmental Exposure

Current Environmental Health Reports (2022)

-

Hokkaido birth cohort study on environment and children’s health: cohort profile 2021

Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine (2021)

-

Transcriptome profile of Dunaliella salina in Yuncheng Salt Lake reveals salt-stress-related genes under different salinity stresses

Journal of Oceanology and Limnology (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.